SEVEN

To the Potting Shed

When the cheering had died down and Magnus had scaled the table to be introduced to the rabbit (‘Call me Uncle Roland, dear boy!’), it was plain to all that the wire mesh was far too small to allow him to enter the hutch. He could not even get his foot through it.

‘Bite it!’ said Magnus, and his excitement at the idea, coupled with his raging hunger, forced from him the longest speech of his young life. ‘Magnus make big hole!’ he said. ‘Come inside Uncle Roland’s house! Eat all food! Nice!’

Madeleine beamed with fatuous pride at these remarks, while Marcus Aurelius considered them critically.

‘Such a course of action is undoubtedly possible,’ he observed. ‘Teeth sharp enough to cut through a cat’s tail would make short work of this wire. Of that I have no doubt.’

‘Nor have I,’ said Roland. ‘But, I ask you, is it wise?’

‘Wise?’

‘Consider the situation. We are all dependent upon the humans for our livelihood, directly in my case, indirectly in yours, Imagine their feelings this morning when they see their cat. Their bob-tailed cat. An accident, they may suppose. Or next door’s dog. But if on top of that, they come down here – as they shortly will, to feed me – and find not just the evidence, lying down there on the ground, but a great hole cut in the front of my hutch, what do you suppose they will think?’

‘They’ll think something funny’s been going on, said Madeleine absently.

‘No, no, Maddie,’ said Marcus. ‘You do not see what Mr Roland means. The humans will think that he is the culprit. All the evidence will then point to it.’

‘And they eat rabbits,’ said Roland quietly. ‘Don’t forget that.’

At the mention of eating, Magnus, who had not understood the conversation, set his teeth to the wire.

‘No, Magnus!’ cried Madeleine sharply. ‘Mummy says no!’

Surprise made Magnus let go, but this was quickly succeeded by another reaction. Never had he been crossed before, never denied or forbidden anything. He shouted angrily at his mother, ‘Nasty Mummy! Magnus want bite wire! Magnus want food!’

‘Perhaps you should humour him, Maddie dear,’ said Marcus Aurelius uncertainly. ‘We don’t want any unpleasantness.’

‘Unpleasantness?’ cried Madeleine on a rising note. ‘Humour him? I’ll give him what for if he don’t do what he’s told, that’s what I’ll do. You leave that wire alone, Magnus, and you get down off the table, this instant, d’you hear me, you naughty boy?’

There was a moment’s silence and then, in very sulky tones, ‘Magnus bite Mummy,’ said the naughty boy.

At this Madeleine’s control broke. Doting mother she might be, upon this child more than upon all her many previous children, but there were limits. She had been brought up to respect her elders and betters and only to speak when spoken to. ‘Children should be seen and not heard’ – even now she could hear the acid voice of an old maiden aunt laying down this law.

Furiously she shot through the wire and fastened her needle teeth in the tip of her son’s large snout. There followed a squeak of pain, a scrabbling of claws as Magnus tried to keep his balance on the edge of the table upon which the hutch stood, and then a loud thump as he hit the ground below.

‘Serves you right,’ called Madeleine. She turned to Marcus Aurelius. ‘’Tis all your fault, Markie,’ she said. ‘You should have been firmer with him when he were little.’ And she ran down the table leg.

Roland’s nose twitched madly at the expression on Marcus’s face. ‘A very determined lady,’ he said in his deep tones. Marcus made no reply, so he went on, ‘However, we have not solved the problem of feeding the lad, have we?’

Marcus Aurelius still made no answer. His feelings, usually so controlled, were in a terrible muddle. As well as the fear which never left him when outside the safety of his den, he felt still the pride at Magnus’s victory over the cat mixed up with the disapproval of his son’s insolence and the shame of being told off (and most unfairly told off, he said to himself) by his wife in front of this distinguished new friend.

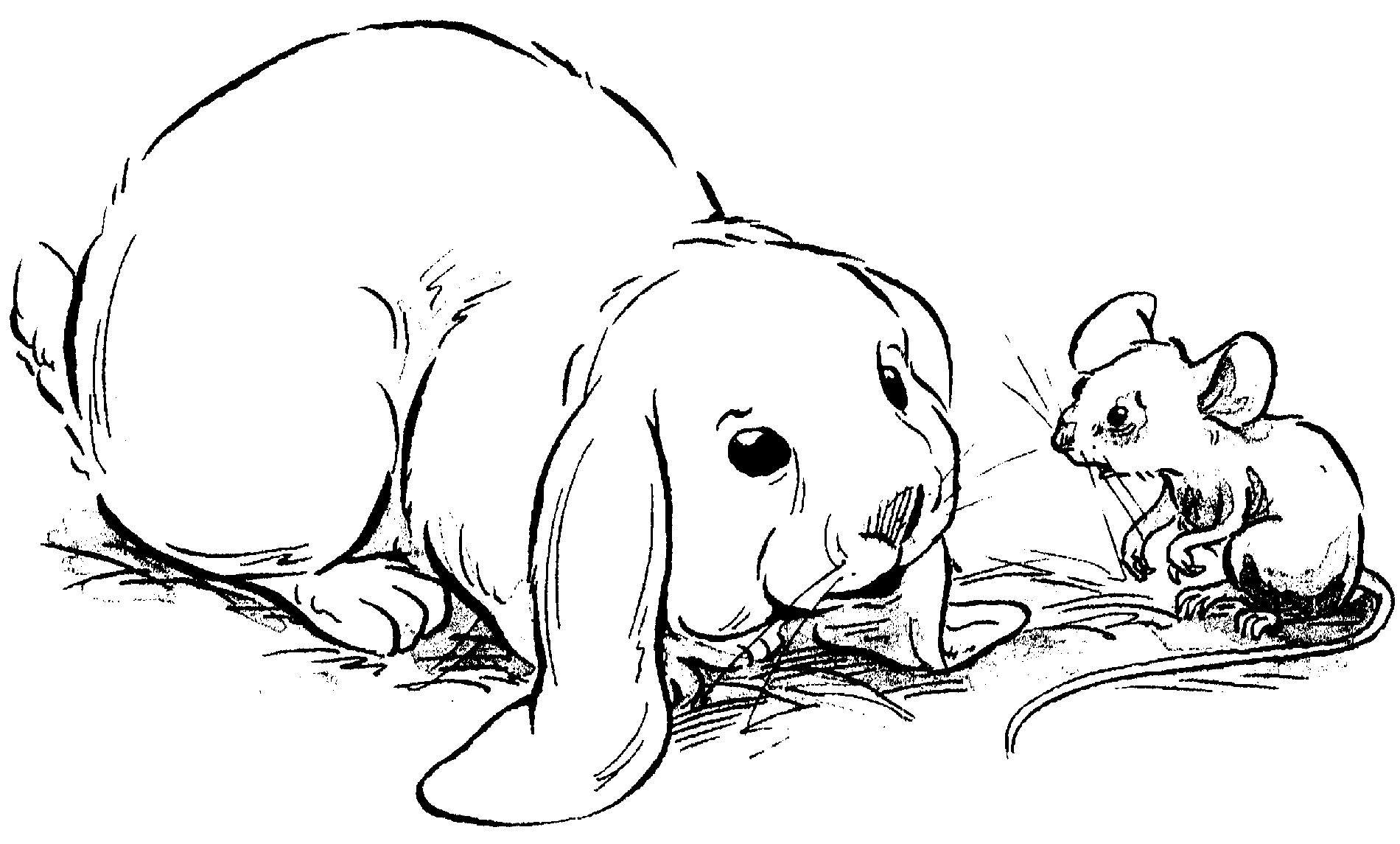

All of this Roland sensed. Below them they could hear Magnus saying plaintively, ‘Mummy hurt nose,’ and Madeleine dealing with the matter as mothers do – ‘You should have done what Mummy told you. Mummy knows best. There, there, don’t cry, Mummy will kiss it better.’

Roland turned carefully towards Marcus Aurelius, his long ears dragging on the hutch floor with a soft slurring noise.

‘Women are good at those sorts of things, aren’t they, old chap?’ he said in a man-to-man voice. ‘But it’s the breadwinners who really matter, eh? Now as head of the family, no doubt your prime concern is to solve the question of an adequate food supply for your boy?’

‘Yes,’ said Marcus.

‘And obviously you have worked out, clever fellow that you are, that there’s a store of this mixture that they feed me, somewhere about the place?’

‘Yes,’ said Marcus.

‘You’re a sharp one. I can see that you know where it’s kept.’

Marcus tried hard to look knowing.

‘My word, yes,’ said Roland. ‘I should have realized that a chap of your intelligence would have known where it was.’

‘You mean,’ said Marcus hopefully, ‘in the . . .?’

‘Exactly,’ said Roland. ‘So if I were you, I’d pop down to that excellent little wife of yours and tell her to stop worrying because you’ve got it all worked out. Be masterful, y’know. But what am I saying? Anyone can see that you’re the master in your own house.’

‘Yes,’ said Marcus.

‘Or, for that matter, in the potting shed,’ said Roland quietly, his nose twitching.

‘Ah,’ said Marcus Aurelius. ‘Exactly,’ he said. ‘As a matter of fact, I was just on my way there.’

Madeleine was amazed, to say the least of it, when Marcus Aurelius came shinning down the table leg and snapped at her in a sharp voice of command.

‘Follow me!’ he said. ‘At the double.’

‘Crumbs!’ said Madeleine to herself. ‘Whatever’s come over the old chap? Hope he knows where he’s going, he’s as blind as a bat.’

She was turning to obey her lord and master when a thought struck her. ‘Magnus,’ she said, ‘pick up thik old cat’s tail and fling un over into next door’s garden, and then come on after us.’ Let someone else get the blame, she thought.

She ran on after Marcus. ‘Where are we going, Markie?’ she panted as she drew level.

‘To the potting shed!’ cried Marcus Aurelius confidently.

The potting shed was in the far corner of the cottage garden, diagonally opposite the pigsty, and much too far away from either their summer or winter homes for the mice ever to have visited. Madeleine, however, knew whereabouts it was and she was reasonably certain that her husband did not. Something told her not to upset his newfound confidence by criticism, so she ranged level with him and by tactfully shouldering him round as they ran got him pointing in the right direction. Behind them they heard the groundshaking thunder of feet as Magnus caught them up.

When they reached the open door of the shed Marcus Aurelius stopped and faced his wife and child. A Moses among mice, he had led his people to the Promised Land, and he wanted the moment to have its full dramatic effect.

‘Here,’ cried Marcus Aurelius, ‘is plenty!’ and he climbed upon a stack of boxes and thus on to a shelf. Upon it, his nose told him – for his eyes were too weak – was the supply of rabbit food. What his nose did not tell him about was the danger that lay between him and that splendid-smelling brown paper bag towards which he rashly bounded. Madeleine saw it but too late.

‘Markie!’ she cried in horror. ‘Look out! Mind the –’ but her words were cut off by that awful sound that comes as a death-knell to many a mouse.

‘Snap!’ went the trap.