NINE

Jim the Rat

The ratcatcher was a well-known figure in the cottages and farms of the village and of the neighbourhood. He was one of those people who seem always to have been around. He dealt also with mice of course, and moles, and anything else that he considered to be vermin, but his chief interest was revealed in his name.

Nobody, not even the smallest children, called him Mr Johnson. To everyone, he was Jim to his face. But behind his back, he was always known as Jim the Rat.

If you remember what the most famous of all ratcatchers looked like, Jim the Rat was the exact opposite. The Pied Piper of Hamelin was ‘tall and thin, with sharp blue eyes, each like a pin, and light loose hair’. Jim the Rat was short and fat, his eyes were the colour of the bottom of a duck pond and he was bald.

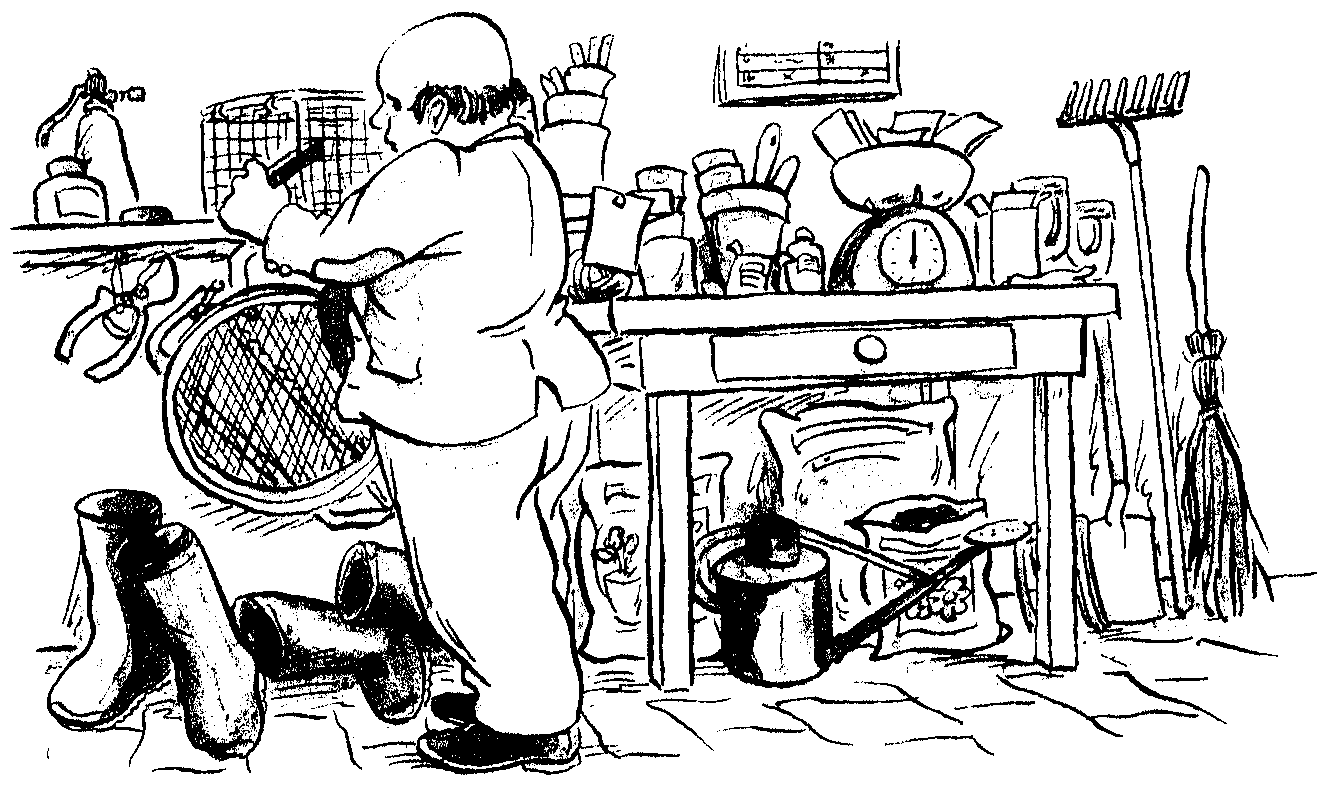

When he arrived later that morning in a noisy old van, Magnus was asleep inside an old gumboot in which he had passed the night. (The potting shed contained a number of old gumboots, all right-footed. The cottager always seemed to get holes in his left boots but he kept the old rights, hoping his luck would change.)

At the sound of human voices Magnus awoke. He debated whether to shout ‘Nasty!’ or ‘Bite you!’ but something told him to remain silent.

‘I should say there was at least a couple of pounds of rabbit food left yesterday,’ the cottager was saying as the two men came into the shed. ‘And it’s all gone this morning, Jim, every scrap of it. Take an army of rats to eat that lot so quick – place must be running with them.’

Jim the Rat took a large red white-spotted handkerchief out of his pocket and blew his nose, very carefully.

The Pied Piper’s nose, one feels sure, was long and thin and pointed. Jim the Rat’s was short and squashy, with big nostrils pointing straight ahead, like a pig’s. He lowered it now to the shelf and sniffed, deeply.

‘No rats here,’ he said.

‘How can you tell?’

‘Can’t smell ’em.’

‘What can you smell then?’

‘Mice.’

‘You can tell the difference then?’

‘Tell ’em all apart – rat, mouse, vole, shrew. Tell the different sorts of mice apart – house-mouse, field-mouse, harvest-mouse. Good nose I’ve got.’

‘Well, what in the world’s been eating my rabbit mixture then?’

‘House-mouse.’

‘Oh, come on, Jim! Polish off two pounds of the stuff in twenty-four hours? And have a look at this trap. See these toothmarks?’

Jim the Rat picked up the trap and put it to his nose. ‘House-mouse,’ he said again. He looked at the empty brown paper bag, noticing how it was torn open. He looked under the shelf, at a litter of old seed boxes and sacks and four right-footed gumboots, one lying on its side. His piggy nostrils flared.

‘Puzzle,’ said Jim the Rat. ‘You’ll have to get some more food for the old rabbit then?’ he said.

‘That’s right. Going down the shop shortly.’

‘Well, put it somewhere else. Not in here. Put it in a tin, a good strong tin. And another thing. Don’t come in here at all for a few days, all right? Anything you need from this shed, take it out now, can you manage that?’

‘What are you up to then, Jim? Going to poison ’em?’

‘No, but keep the cat away. Shut the door.’

‘That reminds me,’ said the cottager. ‘That blasted dog next door, took the end of our Tibby’s tail off. It’s lying there on the other side of the fence.’

Jim the Rat’s duck-pond eyes narrowed, and he looked again at the toothmarks on the trap. ‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Well, I expect you’ll be wanting to get off down the shop. Don’t bother waiting about for me, I’ll be a while yet. You just keep this door shut and I’ll look in tomorrow, all right?’

Jim the Rat waited until the cottager had mounted his bicycle and pedalled away down the lane, and then he fetched a trap from his van. No ordinary trap was this, but the strongest catch’em-alive contraption which he owned. It was the size of a large apple-box and made of metal and heavy-gauge criss-crossed wire. He used it along the river banks, to catch coypu and mink that had gone wild. He put it on the potting shed shelf. To bait it he normally used a piece of meat, for mink, and for coypu some root vegetable such as carrot or beetroot.

‘Something special for you though, I think, my friend,’ said Jim the Rat, and he took from his pocket what was to have been his mid-morning snack, a Mars Bar. He unwrapped it, placed it carefully within and set the trap. He went out quietly and shut the door.

‘I wonder,’ said Jim the Rat out loud, as he drove his noisy old van away down the lane, ‘I wonder,’ and his piggy eyes gleamed.

All his rat-catching life he had been fascinated by a legend, a legend not perhaps as well known as that of the Loch Ness Monster or the Abominable Snowman, but to him, because of his profession, more interesting. It was the legend of the King Rat.

Jim the Rat had read everything he could lay his hands on about this creature of folk lore, stories from many different lands and of many different times. All of them told of one thing in common. In any gathering of rats, especially a large gathering such as might occur in war or plague, or in sewers, or in deserted places whence humans had fled before some catastrophe, there would always be one mighty leader, the King Rat. A giant he was, a huge brute before whom cats would quail and dogs run yelping. Some of the tales told of humans attacked by an army of squeaking, chattering rats, the King at their head. Often this was at night, where a foolhardy man might perhaps have been exploring a cellar, in a ruined town. By the light he carried, a flaring torch maybe, he would suddenly see, even before a sound was heard, a thousand glistening eyes in the darkness and before them a single pair far larger than the rest. If he lived to tell the tale, that is.

And just as many people believe in the Loch Ness Monster or the Great Sea Serpent or Bigfoot, so Jim Johnson believed in the existence of King Rats. He had no proof, it is true. He had killed some big old rats in his time, but they were just big old rats. But he was always on the lookout for something unusual as he went about his business. And this morning he had found it!

It was not just the amount of food that had gone, not just the toothmarks on the trap. His sharp eyes had seen muddy footmarks on the paper sacks underneath the potting-shed shelf. They were very large footmarks, bigger than the average rat’s, as big perhaps as that sole survivor of the Piper’s music, he who, ‘stout as Julius Caesar’, had swum the river to carry the news home.

There was no King Rat in that potting shed but there was something very big, something which his good nose told him of, unmistakably.

‘I wonder,’ said Jim the Rat softly. ‘Could it be a King Mouse?’

Magnus, meantime, had drifted back to sleep. He had listened to the men’s voices, and to various noises ending in the shutting of the door. It passed through his mind, a mind made more than usually slow by the amount of food he had eaten, that he was now a prisoner, but he was warm and comfortable in the old gumboot and he could always bite his way out of the shed when he wanted to.

He woke again when his ears told him of noise and his nose of a particularly delicious smell. He climbed out of the boot and up on to the shelf, and his eyes showed him a scene of revelry.

Half a dozen mice (the cottager had not set the trap that had held Marcus Aurelius for no reason) were nibbling eagerly at the dark brown object from which the lovely smell came. They were squeaking with excitement and joy, and at first they did not notice Magnus. Then one suddenly said, ‘Look out, boys! Rat coming!’ and they all stopped eating and stared.

‘Not rat,’ said Magnus in a rather hurt voice.

‘What are you then?’ said another.

Magnus hesitated, a little shy with these shrill strangers, and a third one said cheekily, ‘Lost your tongue then?’

Magnus felt himself growing angry. ‘Me mouse,’ he said gruffly.

At that they all fell about, squeaking with helpless mirth. ‘Me mouse, me mouse, me mouse!’ they screamed, until, tiring of the joke, they turned their backs on him and fell to nibbling again.

Magnus saw red. One end of the metal contraption in which the mice were feasting was open, he could see, and in through this he dashed with a thundering cry of ‘Bite you!’, so loud as to drown the click of the trap door closing behind him as his weight set it off.

He found himself alone, for the others had vanished through the wire mesh, and in front of him the sweet-smelling object, hardly marked by the tiny teeth that had so far attacked it. Eagerly, effortlessly, Magnus Powermouse picked up the Mars Bar. Holding it in his forepaws, he opened wide his mouth and bit off a large lump.

‘Nice!’ said Magnus, and took another great bite. ‘Nice!’ he said again. By midday the Mars Bar was finished.

‘More!’ said Magnus mechanically.

He looked around for the other mice but there was no sign of them. He looked for the door through which he had entered but there was no sign of it. He butted at each side of the metal box but each side was unyielding. He tried the heavy wires with his teeth but all to no avail. And as he rested a moment, panting with fury and frustration, Madeleine’s words came clearly to his mind from those far-off lessons in the pigsty. ‘Beware thou the trap!’ – he could remember the exact pitch and tone of them now, spoken in that voice he loved so well, that voice that he would never hear again!

At that instant, the day’s strong wind, blowing across the garden from the north, brought upon it the scent of his beloved mother.

He threw back his head.

‘MUMM-YYY!’ cried Magnus Powermouse.