FOURTEEN

A Scream of Brakes

By the time Magnus reached the lane Jim the Rat’s van had disappeared round the next corner on its way to the very place that Magnus himself was seeking.

Jim had searched every corner of his own property unavailingly. I suppose he might have tried to get back home, he thought to himself. I might come across him on the way perhaps. At the very least I can pick up that rabbit they offered me. Make a nice pet. Take my mind off His Majesty perhaps.

But he knew that it wouldn’t. He was already missing the King Mouse very badly.

Magnus turned to follow the direction that the van had taken as soon as he hit the lane. He did not know which was the right way to go, he did not know that the vehicle had been Jim’s van, he did not know why he made that choice, he just made it, in his usual direct fashion. And in his usual direct fashion, he set off walking in the middle of the road.

He plodded resolutely forward, his mind now empty of all thoughts save two. Magnus not see Mummy and Daddy, so Magnus unhappy. Mummy and Daddy not see Magnus, so Mummy and Daddy unhappy.

In fact a firm belief in Roland’s gift of second sight had kept Madeleine perfectly happy.

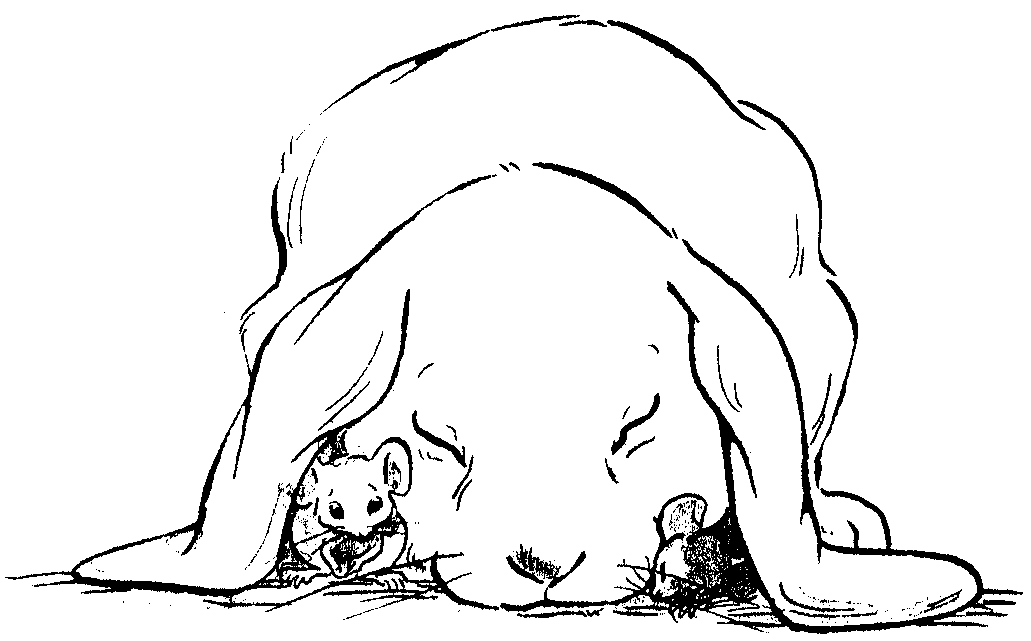

From the start she had found something very reassuring about the great white rabbit with his deep comforting voice and his kindly red eyes and those huge soft floppy ears under which she and Marcus Aurelius slept so warmly every night. And to be told by him, solemnly, certainly, that they would all be re-united – well, that was it then! No need to worry, everything in the garden was lovely!

Marcus Aurelius on the other hand was by no means as confident of ever seeing his son again, that son of whom he had suddenly grown very fond, so he spent much of his convalescence thinking of him. More sceptical by nature than his simple wife, he could not forget the facts of the matter, whatever Roland had said. Magnus had been captured by a human, and humans kill mice. Therefore . . .

‘Q.E.D.,’ said Marcus Aurelius sadly as he peered short-sightedly out of the rabbit hutch at the morning sunshine, some weeks after Magnus’s disappearance.

‘Q.E.D.? What’s that mean, Markie?’ asked Madeleine, emerging from beneath Roland’s left ear.

‘Er . . . quite an exquisite day, Maddie dear,’ said Marcus hastily.

‘Funny way to talk,’ said Madeleine. She giggled. ‘B.S.I.O.W.W.T.S.O.M.’ she said.

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Better still if only we was to see our Magnus.’

‘If only we were to see our Magnus.’

‘That’s what I just said.’

‘Ah. Maddie my love, I pray you may never fall victim to groundless optimism.’

‘I hope I never does. Sounds horrible.’

‘What I mean, my love, is . . . do not set your heart upon seeing our boy again. Nothing is certain in this life.’

‘But my heart is set on it, Markie. And it is certain we shall see him. Uncle Roland said so.’

Roland had been embarrassed by the way the mice addressed him, Marcus Aurelius as ‘Sir’, Madeleine as ‘Mr Roland’. He could not persuade them to use his first name alone, so had eventually settled for ‘Uncle’, a title with which they appeared comfortable.

At the sound of his name he hopped forward and squatted carefully between his two small friends.

‘You did, didn’t you?’ said Madeleine.

‘Did what, my dear Madeleine?’ asked Roland.

‘Say we should see Magnus again. That we should all be reunited.’

‘I did indeed.’

‘What interval of time,’ said Marcus Aurelius, ‘would you estimate must elapse before this happy vision might become reality?’ For the life of him he could not keep a note of sarcasm out of his voice.

‘He means how long before we sees him,’ translated Madeleine, and she could not keep the excitement from hers.

‘Oh, I do not know exactly . . .’

‘Soon?’

‘I sincerely hope so,’ said Roland. He crossed his paws.

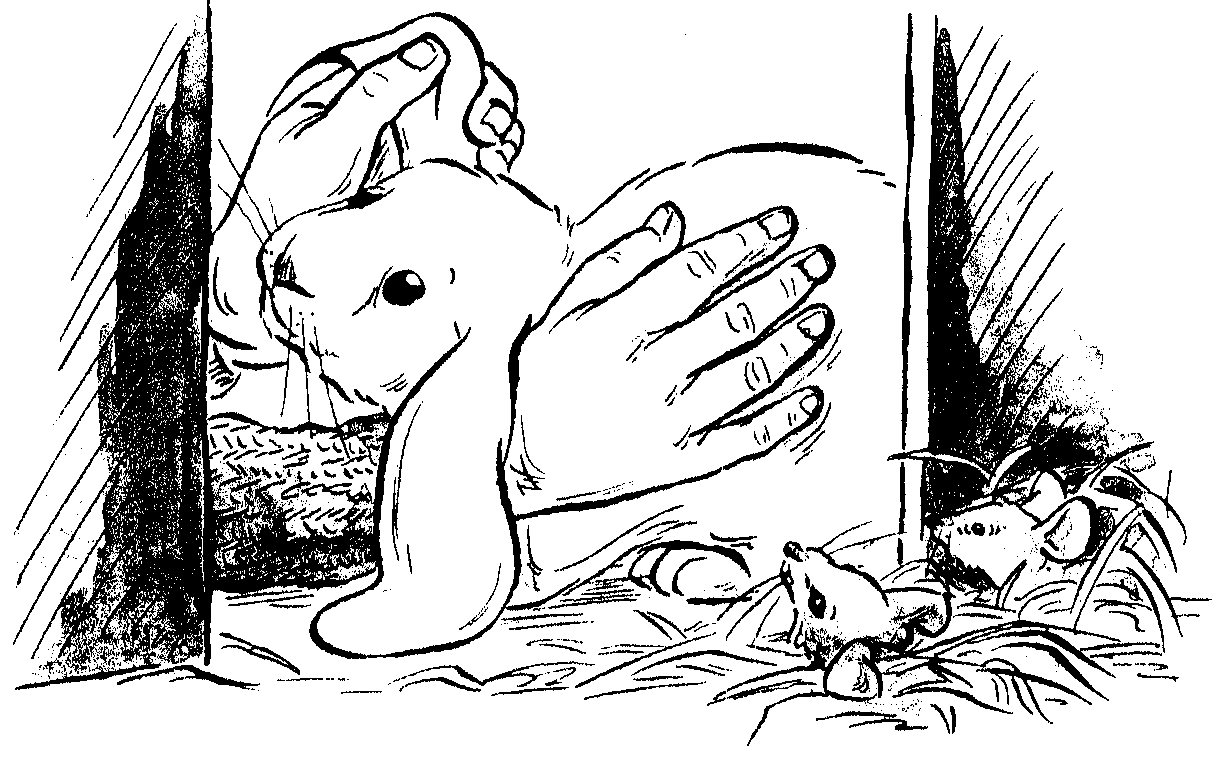

At that very instant there was the sound of a motor coming up the lane. It stopped, the garden gate clicked, and there were footsteps on the gravel of the path. Roland, standing up against the wire door of his hutch, saw the approaching human before the mice. It was the fat man who had taken Magnus.

‘Cave hominem!’ snapped Roland. At this Latin phrase, taught him by Magnus, the mice would dart into the sleeping compartment and hide beneath the hay.

Outside they could hear the rumble of men’s voices, fading for a few moments (for Jim had manufactured an excuse to have a look in the potting shed, hoping against hope) and then strengthening as they returned towards the hutch (Jim’s duck-pond eyes darting everywhere, vainly seeking that familiar figure).

‘Well, here’s the old rabbit then, Jim,’ said the cottager. ‘You’ll give him a good home, I know.’

Madeleine and Marcus Aurelius cowered lower in the hay as the wire door of the hutch was opened. Then Roland felt strong fingers that yet were very gentle as they stroked the arch of his back, rubbed at the roots of his great ears, and finally smoothed the ears themselves, one at a time, softly, tenderly. He shivered with pleasure at the touch.

‘He’s a beauty,’ said Jim the Rat.

‘Right then. Grab ahold of the other end of the hutch. I’ll give you a lift into the van with it.’

‘Markie, Markie!’ whispered Madeleine in terror as the old van went racketing off down the lane. ‘’Tis the end of the world!’

‘Courage, Maddie dear,’ said Marcus Aurelius through chattering teeth.

‘All shall be well,’ said Roland, thrusting in his head from the outer compartment of the hutch. ‘Only stay hidden till I give the word.’

The bumping and the rattling continued, accompanied by violent lurches as they swung round one of the many bends in the twisting road. Then suddenly, after one such lurch, the travellers in the hutch were thrown about as, with a scream of brakes, the van came to a shuddering halt.

The silence that followed was broken by the voice of Jim the Rat, a voice that suddenly sounded old and choked.

‘Oh, no!’ said Jim. ‘Oh, I never saw you, coming round that bend! Oh, Your Majesty, Your Majesty, what have I done?’