CHAPTER FOUR

UTOPIA WITH WALLS

THE CARCERAL CITY

“Earthmen are all so coddled, so enwombed in their imprisoning caves of steel, that they are caught forever.”—Isaac Asimov, Caves of Steel (1954)

To everyone in Diaspar, “outside” was a nightmare that they could not face. They would never talk about it if it could be avoided; it was something unclean and evil.—Arthur C. Clarke, The City and the Stars (1956)

Here’s a story: A young boy or girl grows up in a closed society that is tightly structured in the best interests of the whole. But all is not well. Individual possibilities are limited, and creativity withers. Even worse for the immediate future, things that used to work are breaking down, and the social fabric is fraying and unraveling. The frustrated teenager or young adult chafes at restrictions, rebels, and escapes to a place and a future with more possibilities.

Over the centuries, this plotline has accreted innumerable variations—both Huckleberry Finn and Benjamin Braddock light out for the territories, after all. It is also the structure for a very specific type of science fiction story in which people, for their own good, live in isolated and enclosed cities whose physical form embodies social rigidity. More often than not, these future cities are hidden underground (although walls and domes also come into play). Something awful has happened that made the world dangerous or uninhabitable, driving survivors to a refuge where the authorities regulate the details of everyday life to keep the artificial ecology and the planned economy humming. Young people seldom like adult rules, and they really don’t like them when the machinery of the city is growing unreliable or the social rules limit their choices, so the protagonists declare their independence by finding ways to flee the city for what they hope are wider possibilities.

These underground cities and walled-in cities are urban machines of a special type. They are cousins of the buried and bubbled cities designed for environmental protection, but they are places in which the initial goal of physical protection has come first to expect and then to require social stability rather than exploration—they are exercises in social engineering layered on top of physical engineering. In this plot parabola, society withdraws into the city for protection and survival but sinks slowly into stasis. The protective city, as an end-state utopia, has frozen its possibilities, and its physical limitations represent and enforce those societal limits. The city may have been constructed originally for a material purpose such as safety from nuclear fallout, but it survives as an institutional machine to implement social and political purposes. If you are underground—or behind high walls—the range of your senses and thus your range of knowledge are limited. People are supposed to be happy because they are secure, but a few people see through the superficial harmony, aren’t satisfied, and find ways to rediscover a wider world. A buried city, after all, is a metaphor for a society with its head in the sands … and also for a society that is dead and buried.

These are carceral cities—cities that imprison their residents even with the best of intentions. The term comes from Michel Foucault’s chilling idea of the “carceral archipelago” of physical and social institutions that constrain individual freedoms in the modern era of intrusive government, prying corporations, and ubiquitous surveillance. Foucault started with Jeremy Bentham’s idea of a panopticon prison, a physical space where prisoners would be under constant observation and control, and extended it to the wide variety of modern institutions that regulate and direct individual actions.

Bentham aimed for the moral reform of individual inmates, but anthropologist James C. Scott has expanded the idea to the scale of national policy. He argues that nation states have a tendency to set ambitious goals that take on a momentum of their own—Five-Year Plans, Great Leaps Forward, high modernist cities like Brasília, and high dams across the Yangtze gorges. The slope from beneficial projects and protective regulations to coercive requirements is paved with banana peels. And in the twenty-first century, of course, panoptic society can function without bars and walls, by tracing calls, monitoring key clicks, and tracking GPS locations.1

In the carceral cities of science fiction, social goals and standards of right behavior grow so rigid that isolation becomes absolute and the city becomes a fortress-prison that effectively imprisons its inhabitants for their own good. The goal of safety takes on life of its own. As the buried or walled city strives to survive in isolation, everyone must do his or her part by taking assigned jobs, obeying authorities, turning aside doubts. These places are all walls and no gates, unlike space station cities that are open to commerce or domed cities whose raison d’être is planetary settlement. The structures of confinement that were pragmatically necessary in the initial years have become codified and culturally ingrained. The purpose of the city is no longer to be a safe base for survival or exploration, like a buried city on the moon or a tented city on Mars, but rather simple self-perpetuation, with a population educated, enculturated, and regulated to accept the limits of the city. Residents embrace the city’s limits as well-ordered participants in hegemonic systems like the “good subjects” described by Marxist critic Louis Althusser, people who accept and maintain the practices of the dominant ideology that is embedded in social institutions and the practices of government. They have so internalized the values of their restrictive society that they obey social and cultural norms without needing explicit external controls. In Althusser’s well-known phrase, they work all right all by themselves.

SPUNKY KIDS

In 1962, Place Ville Marie opened in downtown Montreal. This mixed-use development included a soaring office tower over an underground shopping mall that connected to the train station and the Queen Elizabeth Hotel. Over the next four decades, La Ville Souterraine expanded to include twenty miles of interconnecting tunnels, shopping arcades, department stores, hotel lobbies, and subway stations. The Underground City has been a selling point for real estate developers and a boon to Montrealers in cold and blustery Canadian winters, and was imitated on a smaller scale in Toronto. A year after the builders of Place Ville Marie began to put portions of central Montreal underground, French Canadian author Suzanne Martel published Surréal 3000 (1963), soon translated as The City under Ground (1964). Writing for upper elementary children, Martel described a future in which Montreal has been replaced by a subterranean city built under Mount Royal, the seven-hundred-foot-high hill that looms over the central city. The city of Surréal was a response to the Great Destruction that had ravaged the entire planet and supposedly killed off all life, leaving an atmosphere of poisonous gases. “Only those who had taken refuge in the caverns under Mount Royal had been saved. A few people, foreseeing the disaster, had prepared a shelter many years before. These fortunate ones, only a few hundred, had sealed the leaden gates behind them and built a city. Above them, the civilized world had perished, destroyed by the stupidity of man” (19).

A thousand years later, Surréal displays the future-will-be-smooth-white-surfaces aesthetic that dominated the postwar imagination. Inhabitants no longer have hair (too messy in a closed environment), endure disinfecting showers every time they enter their white-walled apartments, take meals in the form of nutritionally balanced food pills, and go by names like Luke 15 P 9 and Eric 6 B 12, the book’s twelve-year-old heroes. All adults have productive jobs, and residents are forbidden to leave. Only four people had ever tried, all of them quickly caught, judged insane, and institutionalized—the municipality protects its own.

It is not a bad city to live in, as long as you are a mildly unimaginative adult, but it’s really boring for active teenagers, and it’s worrisome when the main power source begins mysteriously to fail after an earthquake. Eric’s brother Bernard 6 B 12 bravely finds the source of the problem by slithering along power conduits too narrow for grown-ups. Meanwhile, adventuresome Eric has used a rift opened by the quake to reach and explore the world above, where the air is breathable after all and where a peaceful tribe of Lauranians (from “Laurentian,” presumably) live close to nature. Luke and his brother Paul 15 P 9 save the Lauranians from a plague with Surréal medicines and skillfully use a television broadcast to open the eyes of their fellow citizens to the reality of the outer world, showing flowers, birds, blue sky, and green grass. “We now know that, no matter what happens, we need never be imprisoned underground without air or light,” says Paul. The Grand Council agrees, and the gates of Surréal open to the world of “the sun and moon, and the forests and rivers of prehistory” (153).

Surréal is a benign prison-city with happy families and a leadership that is not too set in its ways. Not so the city in Jeanne DuPrau’s popular City of Ember (2003), another book for avid readers in grades four to eight. DuPrau recycles Martel’s plot in literally darker tones, for Ember is built in a deep cavern and lit by electric floodlights. Beyond the streets of the city are trash heaps, and then outer darkness that can drive you insane with fear. The ambience is Victorian gaslight, given the preciousness of light and the fact that there is a nightly curfew when all illumination switches off, an ambience carried into the 2008 film version. The map at the front of the book is drawn with an old-time look. The streets are “lined with old two-story stone buildings, the wood of their window frames and doors long unpainted. On the streets level were shops; above the shops were apartments where people lived. Every building, at the place where the wall met the roof, was equipped with a row of floodlights—big cone-shaped lamps that cast a strong yellow glare” (17).

The city originated after an unspecified disaster caused authorities to construct an underground refuge to ensure that humans survive; originally it contained one hundred people over age sixty and one hundred babies for them to rear. The city was supposed to remain hidden and protected for two hundred years, at which time a sealed box would open and reveal the instructions on how to leave. The box is entrusted to the mayor, who is to pass it down the line to successors in office. However, it is lost, and the city keeps going to year 241, well beyond design specifications of its infrastructure and the capacity of its supply rooms. Now everything from canned goods to lightbulbs is running out; the generator that provides electricity from an underground river is aging and failing, and blackouts are starting. Everyone is getting increasingly edgy, afraid, and desperate. Some of them join in a cult that expects salvation from the return of the Builders. Others find secret stashes of goods and hoard them or create black markets: “At the supply depot, crowds of shopkeepers stood in long, disorderly lines that stretched out the door. They pushed and jostled and snapped impatiently at each other. Lina [the plucky heroine] joined them but they seemed so frantic that they frightened her a little. They must be very sure now that the supplies were running out, she thought, and they’re determined to get what they can before it’s too late” (100). Ember was set up for people’s own good, but it has become rigid and outlived its usefulness, and it takes young people who have not locked into the routine to break out.

Doon Harrow and Lina Mayfleet, played in the movie version of City of Ember by Harry Treadaway and Saoirse Ronan, epitomize the spunky teens who manage to break free from self-isolated cities in stories about carceral cities. Courtesy Walden Media & Twentieth Century Fox/Photofest © Walden Media & Twentieth Century Fox.

Governance is strict but also corrupt—the mayor is the beneficiary of a secret hoard of food and liquor. Children go to school until age twelve, at which time they pick jobs out of a hat. It is therefore a regimented society, with a place for everyone … and you must work, although it is possible to trade your job assignments, as long as they’re covered, as do twelve-year-olds Lina Mayfleet and Doon Harrow. DuPrau, not being an urban studies sort, does not specify the size of Ember at the time of the story. However, there are twenty-four students in Doon and Lina’s class; if there are the same numbers in each cohort from ages one to eighty, the population would be about two thousand.

Lina and Doon discover and decipher the secret instructions and notify the authorities, only to find themselves wanted as criminals for spreading nasty rumors. Taking flight, they find the passageway that takes them on a long, harrowing journey that finally leads them to the surface of an earth that welcomes them with a rising sun. The story ends as they find a fissure that gives them a view of the lights of Ember far, far below; they tie a message of escape around a rock and toss it down in the hope that the other Emberites will also rescue themselves.

These novels for fifth graders have straightforward plots and simple resolutions—their cities are confining and in trouble, but not malevolent, and escape is possible. In Wild Jack (1974), John Christopher colored the imprisoning city more darkly. He posits a future London city-state whose bosses are much more effective authoritarians than the bumbling leaders of Ember. Oligarchic families enjoy a bucolic post-petroleum city that has arisen after the Breakdown on the foundations of twentieth-century London. Like the other new city-states scattered around the globe, it offers a comfortable life to the elite and a strict regimen for a hereditary servant caste. Walls and guards keep out the supposedly antisocial and dangerous inhabitants of the wild Outlands, “the name for everything outside the boundaries of the cities and the holiday islands. There were roads running through them linking the civilized places, and the ground was kept clear for fifty yards or so on either side of the roads” (6). Electronic monitors and airships fend off threats from Outland barbarians.

The plot is elementary. Clive Anderson, the high-school-age hero, runs afoul of the government because his family is politically out of favor. He endures a nasty reeducation camp on the Channel Islands but steals a boat and escapes to the English countryside, where he discovers a rough-and-ready egalitarian society with Robin Hood (whoops, Wild Jack), a band of merry men (who dress in green!), and Jack’s attractive and woods-wise teenage daughter Joan. The hero overcomes tenderfoot trials and proves his mettle. After more adventures that demonstrate that soft and corrupt plutocrats behind their walls are no match for stouthearted Englishmen, the hero casts his lot with the “savages” of the Outlands, where life will be physically harder but a lot more fun. Clive has escaped the social limitations and metaphorical prison of the city, but thousands of the servants remain trapped in place, perhaps waiting for Clive and Joan to lead a revolution in a sequel that normally trilogy-prone John Christopher never wrote.

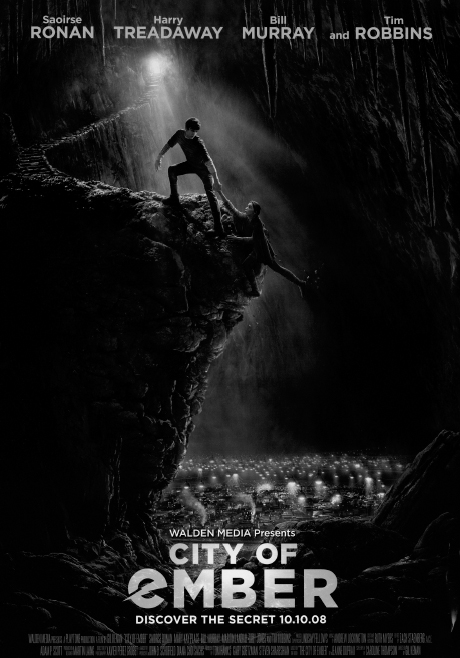

Doon and Lina make their perilous escape from their subterranean city in City of Ember. The looming darkness of the cavern that surrounds the city is both a physical barrier and metaphor for the shrunken horizons of its inhabitants. Courtesy Fox-Walden/Photofest © Fox-Walden.

The Hunger Games trilogy, aimed at eighth graders and read happily by adults, depicts a more conflicted and morally ambiguous world than the ones Clive or Lina have to deal with. As tens of millions of readers and moviegoers know, sixteen-year-old Katniss Everdeen never has the opportunity to enjoy innocence. Her father dead from an industrial accident, she grows up poor and hungry in an impoverished coal-mining community, one of twelve districts of a future North America that are dominated by an oppressive central government arisen out of postapocalyptic war. Like everyone else in the districts, she knows that the authorities in the Capitol may compel anyone from ages twelve to eighteen to participate in an elaborate annual gladiatorial event that has only a single survivor. In The Hunger Games (2008), she survives the game with a combination of physical skill and wit. Catching Fire (2009) shows several of the suppressed districts on the edge of revolt and subjects Katniss to an unprecedented second round of the game. She sees friends killed, and she herself kills to live.

At the start of Mockingjay (2010), District 13 looks like an answer to readers’ prayers. Katniss has been spirited away from the Hunger Games arena and brought to a buried city complex that she thought had been destroyed long before. In fact, District 13 has retained nuclear weapons and exists in a standoff with the totalitarian regime of the Capitol. Dug dozens of levels deep to withstand attack, it is a tightly controlled society on a war footing, where everyone has a job to serve the rebellion that is being fomented in the other districts. It has survived only “due to strict sharing of resources, strenuous discipline, and constant vigilance” (17). Residents wear identical gray clothes and are expected to call each other Soldier Everdeen and Soldier Hawthorne. Each morning a special machine writes their day’s schedule on their arms in ink that disappears only after 22:00. Mealtimes are fixed, seating is assigned, and food is rationed, with portions programmed for individual needs.

District 13 on one level may be a sort of nightmare high school instantly recognizable by preteen and teen readers with its equivalents of assigned seating and class schedules, but it is also a fascist state that strictly limits freedom of movement and access to the admittedly dangerous outside. Katniss slowly realizes that its leaders have been corrupted by their own sense of righteousness and the stress of perpetual struggle against the Capitol. As the other districts rebel in a violent civil war, District 13 offers support but also takes on many of the values of its enemy. Success with the revolution will simply replace an evil regime with a marginally more benevolent tyranny.

Because of her status as a heroine and symbol of rebellion, Katniss does not have to engineer a physical escape from the controlled—carceral—city of District 13. Out of its direct control, however, she makes what we can call a mental escape. As the trilogy moves to its climax, she participates in a mission to infiltrate the Capitol and take down its president—a hollow victory. When the hypocritically ambitious leader of District 13 seeks to restart the Hunger Games with the children of the Capitol as the new victims, Katniss kills her to prevent a new dictatorship. Katniss survives to raise a family, but at the cost of losing her sister and her closest friend. In the moral universe of the Hunger Games, as in other young adult stories, cities require control, and control corrupts the powerful and stifles the young.

VOLUNTARY COMMITMENT

In the year 2805, the starliner Axiom has been carrying hundreds of thousands of passengers on a centuries-long voyage among the stars while Earth slowly recovers from being turned into a vast garbage dump. The passengers have grown grossly fat, confined to mobile chairs that allow them to suck nutriment from tubes and entertainment from giant screens. They are stuck inside the confines of a very large metal container, stuck in their chairs, stuck with the endless recycling of canned experiences. They are comfortable in body and mind, and they know no better, condemned to an endless voyage on a hypertrophied Carnival Cruise ship.

Axiom is literally the cartoon version of a particular kind of carceral city. The starliner figures prominently in the enormously successful animated film WALL-E (2008), in which active, conscientious, and heroic robots help to save humankind by cleaning up their planet and bringing new life into the closed, encapsulated system of the space liner. In so doing, they save the Axiomites from self-imposed imprisonment. Humans have, after all, withdrawn from a contaminated Earth and then settled in for seven hundred years of aimless cruising and contented isolation. The ship, given its size, amounts to a very large, plush, and self-created prison city whose mental chains only the very cute and robotic WALL-E (Waste Allocation Life Loader–Earth Class) and EVE (Extra-Terrestrial Vegetation Evaluator) can break.

WALL-E has interesting ancestors. Ninety-nine years before the film hit the cineplex, E. M. Forster published “The Machine Stops” in the Oxford and Cambridge Review. Humankind in the future has withdrawn from the surface of the Earth, living in underground cities scattered across the globe. Airships allow travel from one city to another, but the overwhelming majority of inhabitants prefer to stay put in small hexagonal cells where the only furnishings are a reading desk and a powered armchair.2 These lumps of flesh with faces “white as a fungus” communicate by hand-held screens (seemingly like Skyping on iPads) and attend lectures by remote broadcast, never stirring from their rooms. The underground urbanites internalize an aversion to the surface as they recycle old ideas and follow the admonition “Beware of first-hand ideas!” Vashti, an older woman who passes her time putting together lectures on “Music during the Australian Period,” is “seized with the terrors of direct experience” when she ventures to try an airship voyage: “She shrank back into the room, and the wall closed up again.” She is more than willing to let the all-encompassing Machine keep her safe and connected to others whom she need never meet in person (253).

The challenge comes from her son Kuno, the rebellious youth and “bad subject” who has the courage actually to visit the surface. There is no good reason to walk the surface, Vashti tries to explain: “The surface of the earth is only dust and mud, no advantage … no life remains on it, and you would need a respirator, or the cold of the outer air would kill you” (250). Kuno sees that his society is dying from inertia, “that down here the only thing that really lives is the Machine…. We created the Machine, to do our will, but we cannot make it do our will now. It has robbed us of the sense of space and the sense of touch … it has paralyzed our bodies and our wills” (266). Kuno’s minuscule rebellion, leaving the underground without an Eggression-permit, earns him the threat of Homelessness—exile from the cities and certain death. Time passes after Kuno’s “escapade,” and the cities grow even more confined. Respirators and airships are abolished, for leaving the underground is determined to be impossibly vulgar and unproductive. And then the Machine slowly and inexorably fails: “There came a day when, without the slightest warning … the entire communication-system broke down, all over the world, and the world, as they understood it, ended” (276).

Isaac Asimov depicted similar—though far less totalizing—cities in Caves of Steel (1954), a science fiction detective story whose plot puzzle requires that the twenty million inhabitants of future underground New York be psychologically incapable of leaving their city for the open air. Each of Earth’s eight hundred cities has become “a semiautonomous unit, economically all but self-sufficient. It could roof itself in, gird itself about, burrow itself under. It became a steel cave, a tremendous, self-contained cave of steel and concrete…. Practically none of Earth’s population lived outside the Cities. Outside was the wilderness, the open sky that few men could face with anything like equanimity” (21). Although the city once had hundreds of exits to the surface, most have been blocked (like those of Surréal). Asimov’s New Yorkers can, if absolutely necessary, venture into the open air, but they really, really prefer that automatic systems harvest their food and raw materials. It is inconceivable that any potential murderer leave the city to approach the isolated Spacer quarter from outside: “Impossible!” says police detective Lije Baley. “There isn’t a man in the City who would do it. Leave the City? Alone?” (66). And yes, indeed, it turns out that the murderer used a robot to fetch the murder weapon, carry it to him through open country, and then return it across the open fields where no human wished to go.

Asimov has a clever solution for a murder mystery in an agoraphobic society, but he also wants to critique the temporary stability achieved through what we might call voluntary commitment to a sort of urban asylum. He posits a three-way tension between the city people who like the comfortable reliability and protection of their caves of steel, a very small minority of Medievalist agitators who want to return mankind to the surface of the Earth, and an even lesser number who are willing to envision breaking beyond Earth itself and sending new generations of people to join the fifty inhabited worlds of the Spacers—the offshoot of humanity who didn’t hunker down and turn their backs on the stars. We end optimistically, in classic science fiction style, with the expectation that Earth’s dirt-bound city dwellers will throw off their mental chains and rejoin their fellows who have been exploring the galaxy.

Forster offered no such optimism as he aimed his “counterblast” at multiple targets, including the supposed technological optimism of H. G. Wells.3 More substantive was the fear of racial degeneration and devolution that Forster’s contemporaries saw as the dark side of evolution and that figures in Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) and Jules Verne’s late story “The Eternal Adam” (1910). To stretch a bit, Forster’s implicit endorsement of the superiority of actual exercise on the planetary surface to chair-bound subterraneality came a year after Robert Baden-Powell published Scouting for Boys, which took Britain a bit by storm. That is one facet of the larger point that self-sequestration is a downward spiral. Like the passengers on Axiom, the Machine-dependent city dwellers have been seduced by convenience to become their own jailers, applauding and even worshiping the system that keeps them confined. Forster illustrates the effects of this voluntary incarceration with a wicked parody of the academic belief that scholarship consists of commenting on other scholars: “First-hand ideas do not really exist…. Let your ideas be second-hand, and if possible tenth-hand, for then they will be far removed from that disturbing element—direct observation…. And in time there will come a generation that had got beyond facts, beyond impressions, a generation absolutely colourless, a generation seraphically free from the taint of personality” (276).

Where Forster envisioned stasis over centuries or millennia (he is not very specific about the date, but people still remember the French Revolution), Arthur C. Clarke extended the time frame to plus/minus one billion years. The City and the Stars, published in 1956 after nearly two decades of sporadic writing and an earlier, shorter version as Against the Fall of Night (1948), is the ultimate novel of the self-incarcerating city. This is a canonical work of science fiction by one of the field’s superstars, read by multiple generations and eliciting a small mountain of criticism and commentary. It is a philosophical parable in which a sweeping vision of the far future is presented as a plea for humankind to think big—to think about reaching for the stars beyond the city.

If the stars are freedom and possibility, the city, of course, is the opposite. Diaspar, the last and only city on Earth, has existed in truly splendid isolation for unknowable aeons. Clarke introduces it in the language of high fantasy of the Lord Dunsany ilk:

Like a glowing jewel, the city lay upon the breast of the desert. Once it had known change and alteration, but now Time passed it by…. It had no contact with the outer world; it was a universe itself.

Men had built cities before, but never a city such as this. Some had lasted for centuries, some for millenniums, before Time had swept away even their names. Diaspar alone had challenged eternity, defending itself and all it sheltered against the slow attrition of the ages, the ravages of decay, and the corruption of rust.

[The people of Diaspar] were as perfectly fitted to their environment as it was to them—for both had been designed together. What was beyond the walls of the city was no concern of theirs; it had been shut out of their minds. Diaspar was all that existed, all that they needed, all that they could imagine. It mattered nothing to them that Man had once possessed the stars. (7)

Imagining a city that survives over millions of years, Clarke is not interested in the social and political processes that might have created it—just that it is the result of a colossal failure of nerve. He does offer a solution for the intellectual stagnation that bothered Forster, however. The minds of residents are stored in a huge data base and periodically reincarnated from memory banks. They live a thousand years or so, get rested, get revived. This combination of immortality and population control leaves the city with a steady state but recycling population. Only 1 percent of all Diasparites walk the streets at one time. The intervals for revivals are staggered and random, so that there is an ever-changing mix: “So we have continuity, yet change—immortality, but not stagnation” (17). Nevertheless, there is the fundamental weakness that nearly infinite permutations of the same people and same memories still add up to change without new inputs. Diaspar is an effort to build a perpetual intellectual motion machine, and we therefore know that ultimate failure is inevitable.

Only one individual has the capacity to challenge the bounds of the city. Alvin is a “unique,” the fourteenth individual in the span of the city who has been newly constituted rather than reconstituted from the memory bank. As a new rather than recycled person, he is first able to understand the limitations of the city and then to take the initiative actually to leave through a subway system unused for aeons. He finds first a bucolic society that looks initially like a real alternative to Diaspar but that proves to be equally committed to the status quo (each society tries to block access to the other in order to fend off change). Eschewing a simple antithesis of bad city / good countryside, Clarke suggests that breaching the walls of the carceral city is not enough.4 Over the course of the second half of the book, Alvin learns that only casting loose the bonds of Earth itself and reaching again for the stars will rescue humanity from its billion-year funk.5

Forster’s story and Clarke’s novel are science fiction milestones, and they are prime exhibits for Gary Wolfe’s carefully developed argument that science fiction tends to depict cities as dead ends. In The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction, he lists several urban traits that are “antithetical to the traditional attitudes of the genre.” As centralized places, cities contradict the SF value of expansion in space. As dense environments, they require enforced conformity and authoritarian rule that sets the stage for “the widespread theme of escaping from the city.” As stable communities, cities are more often stagnant than utopian. As bounded or even walled systems, they limit exploration of a larger world and trap the imagination. As closed systems, cities will eventually run down, perhaps from the gradual failure to support themselves through parasitic control of the countryside or, more important, from the failure to generate new ideas. As Wolfe sums up: “The city is indeed one of the most important iconic images in science fiction, but the ways in which this image is used in the genre suggest that it is less a realization of human plentitude than a barrier to it…. The walls of the cities become images of barriers that must be broken, of a past that must be transcended.”6

What Wolfe presents as the science fiction “icon of the city” (in parallel to the icons of the spaceship, the robot, and the monster) is more specifically a description of the carceral city. In some of his examples, hypertrophied cities are unhealthy, planet-bound alternatives to expansion through space—Caves of Steel, for example. In others, such as The City and the Stars, cities are the antithesis of change, locked-in and locked-down dystopias where only a lonely hero understands the need to challenge the balance. As we shall see in the last section of this book, social theory, from nineteenth-century writers George Tucker and John Stuart Mill to twenty-first-century economist Edward Glaeser, also offers an alternative view in which the variety and sometimes chaos of cities are the true generators of new ideas.

ESCAPE FROM …

The most interesting adult fiction by writers from Forster to Clarke explores the internal dimension of confinement, imagining carceral cities where the residents are their own jailers, bound to the city by its physical comfort and by the security that buffers them from the stress of the outside. In two key science fiction films from the 1970s, in contrast, confinement is more blatant, actively enforced by explicitly totalitarian regimes. The extreme logic of the carceral city is front and center in THX 1138 (1971) and Logan’s Run (1976). Both present physically closed cities whose residents are under tight control in the interest of population management—a hot-button issue of the 1950s and 1960s. Each city is organized around the prime goal of maintaining a steady-state population—meaning that the basic desire to reproduce and/or survive becomes the source of rebellion and motivation for breakout.

THX 1138 was the first feature from George Lucas, expanded and developed from a film-school project. It flopped initially but became a cult favorite when Lucas followed with American Graffiti and Star Wars. Lucas drops viewers into a version of the underworld from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, redone in the stripped-down postwar aesthetic of bare white spaces. Workers have alphanumeric codes for names, just like in Surréal. The authorities dose them with drugs to suppress emotions and sex drive and enforce rules with robot police. Slotted into their jobs, the citizens ritualistically invoke the “blessings of the state” in the manner of 1984. Trouble comes when LUH 3417 (she’s female) alters the drug mix fed to THX 1138 (he’s male). Actual sex happens, and the authorities imprison THX 1138, leading to his escape and flight to the edge of the city along underground roads (the film used unfinished BART tunnels). At the end he reaches the surface to view a sunset for the first time in his life.

Logan’s Run was based on a 1967 book by William Nolan and George Clayton Johnson. Writing when the hippie-radical slogan “don’t trust anyone over thirty” was in the air, they projected a society in which people lived only to age twenty-one before being euthanized. A box office success, the film spawned a short-lived TV series in 1977–78. The film extends the terminal age to thirty, again the reason being a supposed need to enforce equilibrium between population and resources. In the year 2274, residents live in a domed city, multigenerational descendants of refugees from a presumably devastated outside. Logan 5 is an enforcer or Sandman who makes sure that people don’t escape their termination date (echoing the Firemen who burn books in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and anticipating Deckard’s function of tracking down replicants in Blade Runner). At the command of the central computer, he leaves the city in the company of the lovely Jessica 6. What they discover is not the fully functioning alternative society the computer sent them to find, but a wilderness that has the possibilities of social rebirth. Logan returns to the city, where his answers to interrogation by the computer overload its systems, blowing the external seals and allowing everyone to flee the ruined city.

Both films are ultimately unsatisfying as either prison city movie or prison escape movie because they are set in social vacuums. We don’t know why the city where THX 1138 lives is so repressive—it just is—nor do we know how Logan 5’s city came up with such a curious solution for population control. We can contrast both films with the well-loved Escape from New York (1981), which projected a near future 1997 in which urban crime had become so intense that Manhattan has been evacuated, walled in, and turned into a prison colony. Viewers in 1981, already fed a diet of New York–in–crisis stories in news media and movies, could easily imagine a city gone from bad to very worse in a decade and a half. Carceral Manhattan embodied the paranoid fears of both the libertarian right and the radical left that the government was preparing concentration camps for rioters and dissidents, as indeed the FBI and Justice Department considered in the early 1950s. The government eventually decided not to establish “commie camps” (to be used only in an emergency, of course), because of fears that they would offer the Soviet Union a propaganda opportunity comparable to the germ warfare stories that came out of the Korean War. Academics like political science professor Norton Long were simultaneously suggesting that national policy was to turn black ghettos into something analogous to Indian reservations where residents would be confined and fed dribbles of help—only one step short of Manhattan as prison.

On the other side of the narrative arc, viewers or readers of “real” prison break stories know something of what awaits outside Alcatraz or a German POW camp or Devil’s Island, and they are able to anticipate the set of problems and opportunities that may follow the escape. In some instances (The Count of Monte Cristo, The Defiant Ones) what happens after is more important than what happens before. In contrast, we bid farewell to THX 1138 silhouetted against the totally unknown and Logan, Jessica, and other city dwellers fleeing into a wilderness.7 We observe well-justified rebellion, but to what outcome we do not know.

Far more challenging than THX 1138 or Logan’s Run is “Escape from Topeka,” known in actuality as “A Boy and His Dog,” a novella published by Harlan Ellison in 1969 and made into a low-budget movie in 1975. Whereas things turn out very promising for Doon and Lina, and Katniss is able at least to settle into the semblance of a normal life, even if haunted by her past, not so for Quilla June Holmes in “A Boy and His Dog,” where the story line twists and inverts the spunky kid plot. Spunky, plucky, doughty, or spirited … these adjectives might work for Paul 15 P 9, Lina, Clive, or even Katniss, but we are not likely to use them for either of the leads in Ellison’s dark story of the year 2034. After two world wars, the surface of North America is the province of roverpaks, gangs of violent young men who live and loot among the ruins. Below the surface are “downunders,” entire underground cities that have reproduced a nostalgic image of the early twentieth-century town as understood by “Southern Baptists, Fundamentalists, lawanorder goofs, real middle-class squares.”8 This was not a compliment coming from Ellison, notorious for self-defining as one of the coolest people in science fiction and maybe in all of Southern California.

Vic is a solo survivor who roams the surface with his sentient and telepathic dog, Blood. Quilla June Holmes is a luscious young woman from deep Topeka who has been sent to the surface to entice a potent male below to improve the gene pool. Unlike the cities of THX 1138 or Logan’s Run, Topeka wants more sex, not less, seeking survival through intercourse with the surface world. Quilla pulls it off, leading Vic to her city of 22,680 dull, middle-class Americans (that’s roughly the size of Galesburg, Illinois, at the time that Carl Sandburg had just left home and Ronald Reagan was entering school). Topeka is one of two hundred downunder towns that middle-class refugees have carved out of mine shafts and caverns. It covers the floor of a buried tube twenty miles across and 660 feet high, but it looks just like a small town with “neat little houses, and curvy little streets, and trimmed lawns, and a business section and everything else a Topeka would have. Except a sun, except birds, except clouds, except rain, except snow … except freedom.”9 In quick sequence, Vic recognizes the iron hand of social regimentation, realizes his mistake, and escapes the stifling city with Quilla June. Unfortunately, they find an injured and starving Blood waiting for them at the top of the entrance shaft. When Quilla demands that Vic choose between caring for a woman and caring for Blood, he decides that what is needed is fresh meat: after all, “a boy loves his dog.”

In its cult-favorite movie version from 1975, Topeka is cartoonish. Vic first sees Topeka to the sounds of John Philip Sousa played by a fully outfitted marching band that is entertaining picnickers in the park—we are in a parody of Music Man country where Professor Harold Hill might appear at any moment. The town council wear clownish white makeup, and citizens stand quietly to be condemned to death for “lack of respect, wrong attitude, and failure to obey authority.” The original makes the same point without the caricature by simply listing the behaviors that mark the place as quintessentially stagnant and uncool, such as raking lawns, playing hopscotch, sitting on park benches, throwing sticks for dogs, or rocking on front porches (one might contrast Ellison’s take on front porches with James Agee’s eloquent evocation of summer evening in 1915 in Knoxville, Tennessee, at the opening of A Death in the Family).

The combination of well-justified feminist criticism, Ellison’s exploration of the contradictions of the 1960s sexual revolution as understood in its midst, and the extra grotesqueries of the cult movie—plus the ending—have made Vic’s responses to Quilla the center of critical analysis. Most tellingly, critic Joanna Russ raked the film as a boy/dog buddy movie in which the female character exists only to point up the bonds of deep but innocent homosocial affection.10 The movie makes Quilla simultaneously helpless and manipulative. She entices Vic into Topeka and then eggs him to attack the oppressive Topeka administration in the hope of taking over. Thinking she has succeeded in making Vic into her tool, the manipulative bitch who threatens the buddy relationship finds the tables turned at the end when she becomes the means that Vic uses to save Blood.

Revisit the story, however, to think how it might look if Ellison had written Quilla June as the central figure. The writer, and especially the screenwriter, may have made her a cipher and pawn, but a little reflection shows that she would have to be remarkably confident and gutsy to undertake her mission to the surface. Russ acknowledges that the plot requires her to have physical courage and brains to put her life on the line for the betterment of her community by venturing out among the wild boys. She holds her own as she helps Vic and Blood fight off a roverpak and then has the smarts to knock sex-besotted Vic on the head so she can get away and lure him below. Taking this line further, Quilla deserves credit for recognizing the oppression of the city—one of the few residents who can make that mental leap. In their escape she handles a firearm like a pro and shows plenty of Katniss-like gumption in fleeing familiar comfort for dangerous freedom with Vic. What is nasty is the plot reversal: the spunky girl breaks free of her carceral city only to die in a world that is far more dangerous than the one she left. Given that “the War had killed off most of the girls” and that roverpaks tend to greet strange women with rape and murder, Quilla’s death is one more example of how men think only in the short run.

ESCAPE FROM THE GENERATION SHIP

It is a long leap from Harlan Ellison’s world to that of Molly Gloss in The Dazzle of Day (1997), a novel about self-imposed confinement in which it is not a heroic individual but an entire society that challenges and breaks the limits. Gloss is a writer of historical novels and science fiction who is seldom considered in tandem with Harlan Ellison—it’s hard to imagine them in the same room—but The Dazzle of Day takes place in a generation starship that is a physical counterpart of Topeka. Driven through space by vast light sails, the Dusty Miller is a wheel with a central hub and a habitable ring that maintains gravity and supports dense rural settlement on its floor and sloping sides. For several generations its three thousand or so residents have farmed, gardened, maintained mechanical systems, and waited for the voyage to end at what they hope will be a habitable planet. Now 175 years out, the ship has arrived at a solar system with a disappointingly marginal planet. It is cold, rocky, inhospitable, greatly unlike the subtropical interior of the ship with its gardens and vineyards, but it is a place where Millerites could survive if they are willing to adapt and trade what is essentially a Caribbean existence for Iceland or the Hebrides.11

The physical containers may be similar, but the social systems are—of course!—vastly different. Where Ellison deliberately caricatures his Topekans, Gloss draws Millerites as deeply realized individuals. The book is organized around a series of individuals from overlapping families, each of whom is commendable and flawed at the same time. Gloss understands the intense physicality of people’s existence as they work the soil, eat, sleep, and have sex. She describes in detail one character’s experience of a stroke and the effects of a flulike plague on housing clusters. When people live close together in apartment complexes with shared spaces, they hear what’s going on next door and know each other’s business.

Generation ships occupy the overlap zone of spaceships, space stations, and cities. A generation ship is a large habitat that is dispatched, usually from Earth, to carry colonists to a new planet through real space-time. Without benefit of wormholes and hyperdrive, the trip will take multiple generations, with those in the middle decades or centuries knowing only the ship. It is an enclosed, self-sustaining environment like a space station. It moves like a starship. It has some of the social complexity of a town or small city—although not, of course, contact and commerce. If residents of the carceral city are waiting through time for a new world (that is, for the Earth’s surface to again become habitable), the people inside a generation ship are voyaging to new worlds through time and space. Generation ships are thus protective mini-cities whose purpose is directly or indirectly to preserve the human race.

The problem with a generation ship is social entropy—falling into chaos or congealing into stasis. Since the 1940s, the plots in these stories have used the premise that people after several generations have forgotten that they are in a ship and have come to see it as the whole world. It requires a brave young misfit, if not a spunky kid, to test the boundaries, challenge the old ideas, and find the truth—that there is a control center that has been forgotten (Robert Heinlein, “Universe,” 1941); that the ship is actually in orbit around a planet but no passengers know it (Brian Aldiss, Non-Stop, 1958); or that it has already landed on a hospitable planet and all but a few passengers have been too scared to come out (Chad Oliver, “The Wind Blows Free,” 1957). They are, in short, ironic breakout stories about confinement that has been self-imposed through the loss of knowledge and nerve. As science fiction scholar Simone Caroti points out in The Generation Starship in Science Fiction: A Critical History, 1934–2001, these are also generational stories, about knowledge and passion that is or is not passed down over time and thus, in essence, family stories, with the inhabitants of the generation ship as a large family.12

In The Dazzle of Day the crew/inhabitants of the Dusty Miller (on Earth a foliage plant with soft silvery leaves) are Quakers who value simplicity in life and make decisions through group discernment that looks like consensus to outsiders but is an explicitly spiritual practice. The novel starts with a chapter set in Central America before the ship departs and ends with a chapter showing a younger generation responding to the challenge of their new planet. In between the Millerites have to decide what to do. Should they choose this planet, unpleasant as it seems, or should they keep going for another fifty years to the next solar system? It means that in between there is a lot of talk. There are conversations among individuals and in the context of Quaker “meeting for business” in which there are no motions or votes, but rather the expression of views and opinions by anyone present until a sense of the meeting emerges, or sometimes fails to emerge.

The Dusty Miller has become a mental prison through its familiarity. The ship encapsulates and protects its inhabitants, but at the expense of a quietly mounting sense of unease and dissatisfaction. In meeting for business, we hear speakers voice practical concerns about the new planet and, simultaneously, their comfort with the familiar. If they are seriously thinking about dismantling their ship to reuse its elements on the new planet, why not stay in the ship and save the trouble? “What is the point of taking the Miller apart and rebuilding it down there? It think it’s crazy, this scheme…. If we’re going to go on living under a roof, we ought to just stay where we are … [where] people with arthritis can go on without the weight getting into their bones” (209). That comment triggers more: “I don’t see why we need to come out into the sunlight. We’re doing pretty well, after all…. This place is an Eden, it’s the body of God…. We ought to just stay right here” (210).

As the meeting continues, other voices arise. Millerites may fear the new, but they also fear for the future of their ship. Social pressure can be intense in a community with no physical escape valve—no hills to head to, no rivers to cross. Many suffer šimanas, feelings of loneliness and powerlessness that lead to depression and sometimes suicide. Systems may function smoothly from day to day, but as one says, “We’re living in a mechanical thing, eh? And we’ve got to work hard to keep it from going to ruin. People can’t be expected to carry such a burden, can they?—knowing it’s our human intervention prevents the whole world from collapsing” (216). Having started with ideas about reproducing a protected environment on the planet, then veering into arguments for avoiding the surface entirely, the group finally acknowledges that the Miller is frightening as well as comforting. They begin to hold up the value and excitement of taking the planet on its own terms and re-entering the natural world: “We ought to be listening to this New World instead of asking it so many questions.” “We ought to be asking ourselves whether there’s a place for us there, and what it is” (216).

The meeting ends without obvious resolution or summarizing speeches, but with a growing sense that the ship is a prison that has locked people’s minds and spirits into narrow tracks. In this carefully structured book, Gloss does not follow this understated climax with dramatic action. Instead she rounds out part of the shipboard story by resolving a deep tension between an estranged married couple who are two of the main characters. She doesn’t care to show any details of the follow-up decisions or the initial colonization. Instead, the epilogue skips ahead by decades to show the planet-born now adapted to a new life, having found through much trouble what kind of place the new world had for them.

The Dazzle of Day challenges the standard formula of the generation ship story in specific and the carceral city story more generally. Comments on sites like Amazon show strongly polarized reactions, with complaint after complaint about the lack of action. Science fiction writer Jo Walton has commented that “I’d have hated The Dazzle of Day when I was eleven, it’s all about grown-ups … and while being on the generation starship is essential to everything, everything that’s important is internal…. If there’s an opposite of a YA book, this is it.”13 So Molly Gloss does several things to stretch the limits of the carceral city. As Walton notes, Gloss shows that middle-age people as well as rebellious youth can understand the need to break away from imprisoning places and ideas. By depicting a society that can think its way out of a trap by community process she challenges the science fiction model of hero/heroine adventure stories (there doesn’t have to be an escape scene to get out of this imprisoning environment!). She quietly critiques utopia, imagining a well-designed and democratically managed community that doesn’t fail spectacularly, just begins to run down with lack of new energy. And she offers the possibility that societies have the capacity to reinvent and reimagine their futures—making this, after all, mainstream science fiction and grounding the high-flying message of The City and the Stars in the lives of believable human beings.