One

‘I Am Your Storyteller’

‘Oh voice of Spring of Youth

Heart’s mad delight,

Sing on, sing on, and when the sun is gone

I’ll warm me with your echoes

Through the night.’

Enid Blyton, Sunday Times, 1951

Enid Blyton,

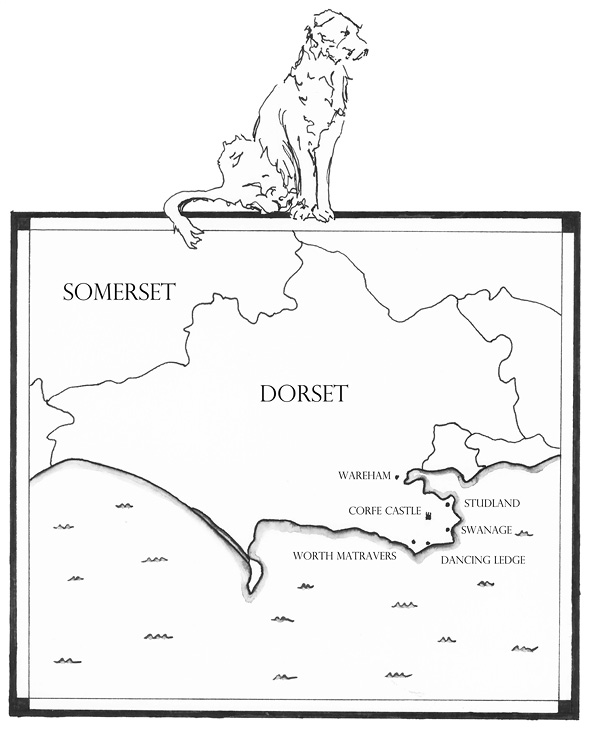

Swanage and the Isle of Purbeck, 1940–1960s

It is April in the Dorset seaside resort of Swanage and the town is struggling to emerge from a long and grisly winter. Not ice-bound, exactly, but the last few months have been dank and chill and unremittingly dreary. Only last week, the ‘Beast from the East’ had lashed the peninsula’s narrow lanes and calcareous hills with a clogging, heavy snow; now it has returned (a ‘mini-beast’ the papers are calling it), but this time with a supercharged wind, gusting up the Channel, flailing a couple of panicking teenagers on the esplanade and shepherding the town’s elderly smokers into the uneasy sanctuary of the bus shelter. Everything, everywhere, is being clawed and rummaged by a foul sleet and the streets are slick with last season’s grime. It is, I am certain, the kind of day that Enid Blyton would have described as ‘lovely’.

Enid Blyton had no time for bad weather. There really is no such thing if you are wearing the right clothing. And perhaps that is why she always spent her holidays in Swanage and almost never visited sunnier lands. There may have been other reasons, but anyway she was ambivalent about America, disliked Walt Disney and – while we are at it – was perpetually disappointed in the BBC. Nor did she much care for children who had no interests other than the cinema; nor spoiled, selfish and conceited children; nor mothers who left their homes and their husbands to pursue careers (although this is undeniably odd given her own hard-fought success). As soon as she could, she avoided her brothers and cut her mother dead. She disapproved of divorce, and first husbands (the heavy-drinking type), and the sour opinions of grown-ups, and said she loathed lies and deceit. She was desperately unhappy if she couldn’t write, but hated sitting still. And when she was writing, she feared (but used) her subconscious and avoided convoluted plots. She found other people’s illnesses alarming or tiresome, along with people with ‘inferiority complexes’, or anyone who gives up; and she preferred children who are ‘ordinary’ or ‘normal’ (although where did that leave her own two daughters?); and she disapproved of cruel, sad tales (Grimm in particular), and girls who think of nothing but boys (‘disgusting’), and things that are frightening, and cruelty to animals and birds (especially that: ‘I think both those boys should have been well and truly whipped, don’t you?’); and interruptions to her work; and silence.

So, it is complicated. And I am sure it would be just as easy for any of us to draw up a list of the things that rile and enrage us – but it is good to remember that there was as much (and more) that Enid Blyton loved. Practical jokes, for example, and laughter. Birdsong. Cherry blossom. The sight and feel of cut flowers. The sea. Summer holidays in the Isle of Purbeck, when she would put aside her typewriter and swim around the pier and play tennis, and finish the prize crossword, and read Agatha Christie novels, and take long walks across the moors, and play with her children, Gillian and Imogen, and transfuse her love of nature straight into their eager young hearts. A round of golf (or sometimes three) in the afternoon. Country lanes. A game of bridge (especially winning). The sunshine of the woods and commons. Her dogs, gardens and husbands. Writing. Writing. Writing. But above all she bathed in the love of the millions of children who devoured her books, and clamoured for her attention, and came to her readings, and joined her clubs, and pursued her with gifts and letters, and visited her at Green Hedges, the large, mock-Tudor home she named and nurtured in Beaconsfield (although, we still have to ask: where did that leave her own two daughters?).

Enid Blyton adored Swanage. Once she’d discovered the place (in the spring of 1931, on a day trip from Bournemouth where she was holidaying with Hugh Pollock, her first husband, and pregnant with her first child, Gillian), she came again and again, often three times a year, sometimes staying for weeks at a time. On that first trip, as she told the ‘Dear Boys & Girls’ in a letter to Teachers’ World, she came soaring over the hills on the road from Wareham, driving her ‘little car’, and saw ‘the ruin of an old, old castle’ on ‘a rounded hill’. It is hard to shake the idea (it’s the way she writes) that here is Noddy, rattling into Toyland with grumpy old Big Ears in the passenger seat, rather than Enid crying with delight at her first glimpse of Corfe Castle (and Hugh, hands tight on the wheel, his mind already drifting towards the first strong drink of the day in the lounge bar of the Castle Inn).

The castle hasn’t changed much since. Excitingly, the jackdaws that Enid wrote about are still here, dozens of them, puffing up their grey-black feathers and asserting noisy ownership over the ruined battlements. On the day I visit, and sit where Enid once sat, on the soft grass that now covers the old moat, I find their bright, blank gaze disturbing. They stand too close, watching all the time, and seem to be choosing which part of my flesh they’d like to snag with their sharp beaks. But Enid loved them. ‘“Chack!” they cried, “Chack, chack!”’ as she wrote in her letter to the young readers of Teachers’ World; and then, in the very first of the Famous Five books, Five on a Treasure Island, here they are again, swarming all over the ruined castle on Kirrin Island, ‘Chack, chack, chack!’ – with Timmy the dog leaping into the air and snapping at their cowardly hides.

Everyone is convinced that Corfe Castle was the model for Kirrin Castle, but Enid would never say, and when I ask the taxi driver if it is true (he’s a local man, brought up in Corfe, speeding me through the village on the road from Wareham Station to Swanage), his answer is a succinct and scornful ‘No’. It is possible he just doesn’t want to talk about Enid Blyton. If you only have the output of the BBC to go on, or the memoirs of her second daughter, Imogen, then you are going to be under the impression that Enid was a dysfunctional narcissist, a cold-hearted snob, a racist and the worst of mothers who preferred the company of children she’d never met to the grating shrieks and demands of her own. Perhaps the people of Corfe have had enough of the association. Until recently there was a Blyton-themed shop in the village, called Ginger Pop, but the owner closed it down because the guardians of Enid Blyton’s copyright were traducing her memory with a load of overpriced spin-offs and politically correct rewrites. At least, that’s how she saw it. She was also irritated by tight-fisted browsers who told her what a lovely shop she was running, but then wandered out without buying anything. There was also, apparently, a spot of bother about some golliwogs in the window.

Anyway, my taxi driver is much more interested in talking about the second homes that are sucking the life out of the village. Enid Blyton never owned a house here, although in 1956 she did buy a farmhouse in north Dorset. She didn’t live there – it was rented and used as a working farm – but she did set her eighteenth Famous Five book, Five on Finniston Farm, in its ancient and mysterious passageways. In 1940 Enid had decided to take a room with her two young girls at the Old Ship Inn in Swanage. The place was hit by a Luftwaffe bomb later in the war, after which she tried the Marine Villas on the front and then, as her fame and fortune blossomed, she moved on to the Grosvenor Hotel (since demolished, mercifully; it looked as ugly as a burst spleen). When she tired of the Grosvenor’s pretensions, she tried the Grand on the east side of town, which is where I’m heading.

The taxi driver has moved on to the topic of crime. He says there is none (or nothing worth mentioning), and that the people of Purbeck just step out of their homes leaving their front doors unlocked without a backward glance. This is also just about the first thing the late-night barman tells me when I arrive at the Grand (‘I moved here from Kilburn and it’s nothing like that; it’s more like you’re living in the 1950s or ’60s. No one ever locks their doors’). And again with the two other taxi drivers I meet on the Isle of Purbeck (‘Leicester’; ‘1960s’; ‘Huddersfield’; ‘1950s’; ‘never lock my front door, ever’). I can only hope that there are no burglars reading this (living in the here and now, finding it hard to make ends meet among the well-locked doors of London or Liverpool). They’d fill their boots.

Still, this is clearly something that draws people to the Isle of Purbeck. The hope that they can sidestep everything that has gone wrong elsewhere: splintered communities, broken homes, soaring crime rates, metrification. It’s a backwater wrapped in a time warp. And although the Isle of Purbeck is not a real island (it’s a peninsula, in the shape of an upside-down goat’s head, bounded by the River Frome to the north and a small stream near East Lulworth to the west), I suspect this desire to seal herself off is what brought Enid here too. Even in 1942, when Vera Lynn’s latest hit, ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, was playing from every gramophone in the land, Swanage must have felt like a place out of time and cut off from the rest of Britain.

There are mixed messages about Swanage in the guidebooks of Enid’s day. In 1935 Paul Nash denounced the place in the Shell Guide to Dorset as ‘perhaps the most beautiful natural site on the South Coast, ruined by two generations of “development” prosecuted without discrimination or scruple’. The Penguin Guide to Wilts and Dorset (1949) is more forgiving, and I prefer to think Enid had this one on her hotel bedside table. ‘Swanage’, the writer purrs, ‘is an outstanding example of the little fishing village grown up into something better.’

Today, the brutal wind is making it hard to get a fix on Swanage. A mucky brown scurf has gathered in foamy clumps where the sea meets the shore. It is especially thick at the groynes, where occasionally it is whipped up and flung onto the esplanade, scattering into tiny flecks that fly through the air before fizzling out on the windscreens of neatly parked cars. Inflatable beach toys are bucking against each other in the shop fronts, shaking off sprays of sleet and squeaking in plastic distress. Damp bunting is pressed against the awnings. The shops and streets are almost deserted. It’s cold outside, but inside the Ship, where Enid (aged forty-two) stayed with Gillian (eight) and Imogen (five) in 1940, they are showing a Premier League football match on the wall-filling TV and there’s the close, happy atmosphere that all good pubs have when the afternoon is young, the weather is wild, a fire is burning, and everyone has decided that they might as well stay for another. A man leaning heavily on the bar tells me that the local Purbeck beer is good, but he draws a blank when I ask him about Enid Blyton. He moved here recently from somewhere in the North (Preston, was it?), and (gesturing vaguely) lives just up the road. I ask if he has locked his front door and he gives me a sharp look.

In mid-1940 Enid had been married to Captain Hugh Alexander Pollock for fifteen years, although Hugh was not on holiday with his family this time. He was probably at home at Green Hedges, helping organize the local Home Guard, which he’d joined a few months earlier. Hugh was a veteran of the First World War, too old to fight in this latest conflagration (he was fifty-one), but desperate to do something. He’d first enlisted in 1912 – he was an army regular by the time the First World War started – and for four years he’d seen almost continuous service in Gallipoli, Palestine and France. After the war ended, he’d stayed on as a temporary captain in the Indian Army, before becoming an editor at the London publishing company George Newnes. It was here, almost as soon as his feet were under the desk, that he had written to Enid Blyton, an inordinately ambitious, but so far only moderately successful, children’s author, and suggested that they collaborate on a book about zoos. He met her for the first time, briefly, in his offices on 1 February 1924, an event marked by Enid in her diary:

Met Phil [a female friend] at 2.45 & we went & had coffee together till 3.30. Then I went to see Pollock. He wanted to know if I’d do a child’s book of the Zoo! He asked me to meet him at Victoria tomorrow to go to the zoo. I said I would. Home at 5.

Now, I don’t know how much of what follows was commonplace in the world of publishing in the 1920s, but Hugh clearly had more on his mind than books and zoos. His transparently cunning suggestion was that he and Enid should meet at Victoria station (she would travel up from Surbiton, taking time off from her work as a nursery governess), before proceeding to Regent’s Park and London Zoo, where they could discuss the possible book. In the event, things moved bewilderingly fast, as Enid noted in her diary entry for 2 February, the very next day:

Met Hugh at two. Went to the Zoo and looked around. Taxied to Piccadilly Restaurant and had tea and talked till six! He was very nice. We’re going to try and be real friends and not fall in love! – not yet at any rate. We are going to meet again tomorrow.

And so they did. The next day they were discussing ‘the zoo book’ over a long walk in the park followed by tea in the Piccadilly restaurant. Enid was dazzled by this trim, authoritative, older, military man (he was thirty-five to her twenty-six). And when Hugh (after just two days) tried to suggest to the ferociously focused Enid that their friendship should be ‘platonic for 3 months’ and (in a letter written on 5 February) that he was ‘fond’ of her in ‘a big brotherly sort of way’, Enid raged in her diary: ‘I’ll small sister him.’ The next day (just four days after they had met for the first time), Enid wrote:

Wrote a long letter to Hugh till 9 telling him exactly what I think. Guess he won’t like it much, but he’s going to fall in love if he hasn’t already. I want him for mine.

And that was that. If Enid ever wanted something, she tended to get it. Sure, there were some hurdles along the way, but the end was never in doubt. For one thing, Hugh had to let his first, estranged wife know that he wanted a divorce. He’d married Marion Atkinson in 1913 and they’d had two boys (the elder, William, dying in 1916). Marion had left Hugh for another man when he was away fighting – and I’m sure this rejection explains another part of the appeal of Enid for Hugh. In most ways she really was very young for her years, and Hugh craved unwavering commitment.

Progress, as mapped out in Enid’s diary, was breathless. On 21 February she had ‘a glorious love letter from Hugh this morning. Such a lovely, lovely one. He is a lovely lover.’

On 23 February ‘We had taxied to Victoria and Hugh took me in his strong arms & kissed my hair ever so for the first time. We had dinner at Victoria & I caught the 10.30 train. It was a lovely, lovely day. I do love dear, lovely Hugh.’

On 29 February they went to their first dance together (‘I loved it & loved it’), and through March they dined at Rules in Covent Garden and strolled in Embankment Gardens and the Tivoli. By the end of the month they were shopping for signet rings together. In mid-April they were on holiday in Seaford (‘We went for a walk to Hope Gap, & sat on the downs, & Hugh was a darling lover’); she missed him horribly when he went back to London. In early June Hugh presented Enid with a ring (‘it’s a LOVELY one’). July found them flat-hunting in Chelsea. And on 28 August 1924 they were married at Bromley Register Office. It was a small affair – with no room for her mother.

If Hugh was looking for uninhibited innocence, someone to soothe his wartime nerves with love and fill his days with chatter and japes, then Enid (who’d hardly been to a dance, or dated a man, but who was burning with pent-up desire for a husband, and her own children, and kittens, and a fox terrier, and a cottage with roses and honeysuckle clambering at the door and her very own garden, heaving with hollyhocks, pixies and frogs), then Enid was manna from heaven. And perhaps what Enid didn’t notice, or understand, was quite how deeply Hugh had been scarred by the war. Even in their first weeks they would ‘row ferociously’. They argued over who would be ‘master’ in their marriage and after a miserable day Enid was glad to tell Hugh that it would be him. Enid gave her ring back at least once. She discovered that Hugh could draw from a bottomless well of possessive jealousy – he even managed to be suspicious of an unknown man who was coming to stay in their boarding home when he and Enid were taking a short (chaperoned) holiday. On 7 May she had written in her diary: ‘But oh I do so wish he would get over his jealousy. It makes me afraid of marrying him.’ And perhaps, also, Enid didn’t grasp the significance of Hugh’s frequent ’flus and food poisonings and occasional absences and dark moods. He had surely been drinking hard since the war, and despite Enid’s hopes that she had found someone ‘masterful’, she (with her unwavering certainty and bright clear path to the future) was in truth a lifeline flung to a floundering man.

And they loved one another – wholeheartedly and thrillingly. It’s too easy to poke around someone’s diary (especially, let’s face it, Enid Blyton’s) and find things to snigger at. Her language is limited (just how ‘lovely’ can everything be?) and at times jarringly old-fashioned. She buys a ‘ripping new attaché case’. They go to see Jackie Coogan in Long Live the King and ‘it was topping’. She misses Hugh when he’s not there and ‘it’s BEASTLY’. His ‘eyes were as blue as the water’ she confides, or sometimes ‘the sky’, and on 22 March, on Hugh’s first visit to her home, ‘We stayed in the drawing room by ourselves and Hugh loved me tremendously.’ But not like that! Because before you start imagining a scene that never unfolded (or at least not yet), it turns out that on this occasion Enid was simply sitting at Hugh’s knee while he read Kipling at her.

It is hard to believe that there really was a time when millions of people talked as though they were stopping off for tea and a restrained and unconsummated affair at a station café in Carnforth. Clipped and constipated. Ripping and topping. But there they all were (it wasn’t just something they put on for the films and the newsreels) – and (to state the bleeding obvious) their emotions and actions were just the same as ours. To take one tiny example, here is an entry in Enid’s daughter Gillian’s diary from July 1946: ‘Today I got 7 for French. We swam in gym. It was wizard.’ And indeed I grew up in a household where my mother (born 1922) was always asking me to ‘go and make love to’ my aunt or the elderly next-door neighbour, and all she expected (I presume) was for me to ask them nicely to lend us some sugar or help with the hoovering. Perhaps what needs saying is that the language Enid Blyton uses in her books may have dated, but it was undeniably authentic.

Anyway, enough of that. The weather hasn’t improved when I finally drag myself away from the public bar of the Ship Inn, but I am eager to get on the trail of Enid Blyton. She knew these Swanage streets well – she used to sign books at Hill & Churchill’s bookshop (now closed) and take long daily swims from the beach (a horrible thought on this bitter day). And it was here, in 1940 (with the beach closed and littered with tank traps and the town alert to the possibility of spies and fifth columnists), that she came up with the idea of the Famous Five books, a series of rollicking adventures starring four gloriously unsupervised children and a monomaniacally heroic rescue dog.

Swanage would have been smaller in Enid’s day: more compact and Victorian. But it’s still an easy, fun-loving place (I can see that much through the driving sleet), and its essence is surely unchanged: a fishing village turned pleasure beach, with big wide skies looping over a great scoop of a bay, flanked by low, treeless hills. There’s a jaunty pier, in front of which are the Georgian Marine Villas, where Enid and the children stayed in the summer of 1941. It seems strange to think of Enid ploughing ahead with her summer holidays as the war raged, the children under strict orders to avoid the beach and the freshly poured concrete pillboxes, but instead heading inland to the moors, or east along the coast towards Old Harry Rocks.

That said, Enid had a talent for avoiding inconvenient or distressing developments and even a world war couldn’t disrupt her routine for long, or staunch the flow of words. In 1941 she published twelve books, despite paper shortages; in 1942 there were twenty-six, including Five on a Treasure Island. This ability (or desire) to ignore or blank what she didn’t want to see is not that unusual, of course, and the war years were a time of huge creative ferment for Enid, although it is also incredible to think that she only really achieved her final, world-conquering momentum in the 1950s. Barbara Stoney, in her biography of Enid Blyton, lists an eye-bleeding seventy (seventy!) books published in 1955, including – but most certainly not limited to – countless Bible and New Testament stories, Mr Tumpy in the Land of Boys and Girls, what seems like a dozen Noddy books, another Famous Five outing (the fourteenth), Clicky the Clockwork Clown, a Secret Seven book (the seventh), more adventures from Bobs, her long-dead fox terrier, Robin Hood, Neddy the Little Donkey, Enid Blyton’s Foxglove Story Book, Bimbo and Blackie Go Camping, something to do with golliwogs, Mr Pink-Whistle’s Party (good grief) – and on and on and on.

As I battle my way through the wind and the rain along the fringes of Swanage’s empty esplanade, I come across the Mowlem Swanage Rep Theatre, a squat, square, post-Enid building, heavy with glass and concrete, today showing Peter Rabbit. The very young and the elderly are well catered for in Swanage – you can see it in the many benches and greens and places selling sticky treats – and so indeed are dairy lovers. Parked out front of the theatre is a dark ‘Swanage Dairy’ van, on its side a nicely etched pledge, written large, to fulfil ‘all your dairy supplies’. I remember when my eldest daughter was young how much she loved her Noddy videos, in particular one called, I think, Noddy Helps Out (doesn’t he just), in which Toyland’s milkman is feeling droopily depressed about something. I have no idea what his problem was – I’m certainly not going to watch the damn thing again – but the tape played on an eternal loop, grimly soundtracked by the milkman’s plaintive cries: ‘Milk-O! Milk-O!’ and little Noddy’s insufferable laughter. ‘Milk-O! Milk-O-o-o!’ I have been haunted by his misery ever since. If you think about it, every single one of Enid Blyton’s stories is concerned with resolving someone’s unhappiness – the bullied are rescued, wrongdoers are punished and redeemed, the righteous are rewarded – although she was always adamant that the story was what mattered. The message (‘all the Christian teaching I had … has coloured every book I have written for you’) had to be smuggled in, ‘because I am a storyteller, not a preacher’.

Enid Blyton also said that the ideas for her stories, and the people and places she put in them, did not come from real life but from her prodigious imagination (no giggling at the back, not until you’ve become the world’s bestselling children’s author). She said that once she had enough to get started (perhaps the setting, the main characters and a hazy outline of the beginnings of the first scene) she only had to sit at her typewriter, empty her mind and everything (the people, the fairies, the teddy bears, dogs and dolls, the plot and the dialogue) would all just unspool onto the page. As she put it in a series of letters to the psychologist Peter McKellar, she lowered herself into a sort of trance – think of Homer and his Muse – and the words flowed. So if, say, she had decided to write about a girl’s boarding school, and she wanted the main character to be exceptionally naughty, she would close her eyes and a girl called Elizabeth and her friends and the scenes would appear. All she had to do was write them down. Conversations, jokes, names of characters … she said she didn’t even know where most of this stuff came from. It just billowed out of her.

In her early years she tended to write in the morning, or in the cracks in the day, but later, when she was a full-time author, she would carry on till sundown, working to a rigid routine, breaking at set times for lunch, letter-writing, the crossword, a spot of gardening, tea with the children and supper with her husband. If she wrote 6,000 words in a day that was generally enough to merit a mention in her diary. Over 10,000 were cause for celebration. A Famous Five book could be written in a couple of weeks. She wrote in her autobiography, The Story of My Life: ‘If you could lock me up into a room for two, three or four days, with just my typewriter and paper, some food and a bed to sleep in when I was tired, I could come out from that room with a book finished and complete, a book of, say, sixty thousand words.’

In all she wrote a staggering 750 books, but no one (not even Enid) could be quite sure about the exact number. She had them all lined up in her library at Green Hedges, but there was always a nagging feeling that there was something missing. And it wasn’t just the books. There was the poetry, the plays and pantomimes, the magazine articles (she edited and wrote most of Enid Blyton’s Magazine and Sunny Stories and poured out articles for Teachers’ World), the hundreds of thousands of letters to her young fans, the household she ran, the tennis and golf and gardens, and the adult play (never produced nor seen again after its rejection – it was, said her daughter Imogen, with damning relish, ‘shallow and trivial’ and ‘never reached the stage and would not have run for a week if it had’). There were the illustrations to organize and approve (she had an immaculate eye for what would work: just look at Eileen Soper’s exquisitely evocative Famous Five drawings; or the pin-perfect artwork by the Dutch artist Harmsen van der Beek for Noddy, who seems to have worked himself to death trying to keep up with Enid’s industrial output). And there were the printers to oversee, proofs to approve, publishing contracts to negotiate (she enjoyed that, and spread herself across several different companies), the interviews, the talks to children (and oh how she loved those talks). And her clubs! And the charities, her own and others; she was quietly generous with her time and her burgeoning fortune.

In short, Enid’s days were laden with work. She went to bed early, armed with one small medicinal sherry, got up early and got busy. She was heartbroken when, in the 1950s, people started to suggest that one person couldn’t possibly be solely responsible for this extraordinary deluge of print. She worked so hard, driven by ambition, of course, but also an absolute dedication to her reading public and a desire to get her message across, a message that as the years went by was deliberately posed as a riposte to all that money-mad stuff coming out of America and Disney. And then to hear the rumours that it wasn’t even her creating these lovingly crafted stories, but some kind of Blyton factory, staffed with bored typists, tapping away all day, slipping in the word ‘lovely’ every now and then, after all, how hard could this tosh be, right? It was agonizing. She was so upset that in 1955 she even sued some hapless young South African librarian, who had dared to suggest that ‘Enid Blyton’ was a fraud. Enid won the case, the librarian was forced to apologize, but it didn’t settle the rumours. And also: what kind of paranoid ingrate takes a librarian to court? What, people wondered, not for the first time, does Enid Blyton have to hide? For an author whose public persona was so intimately entwined with her works, this rosy-cheeked, country-dwelling, dog-loving, flower-gathering, pie-baking, laughing, hugging, storytelling mother of two adoring children – any whiff of some alternative reality was potentially devastating.

We can’t say that Enid Blyton invented the author-as-brand (that was probably Charles Dickens). In fact she wasn’t even the first children’s author to package up her life and her books into one appetizing and marketable story (I guess that would be Beatrix Potter), but it is hard to think of any other author, before or since, who worked so relentlessly on cultivating her own success and burnishing her public image. Once she had decided, as a young child, to become an author (and a children’s author at that), she was extraordinarily consistent in how she appeared to the world. She ploughed through every obstacle. She happily admitted to having received dozens (hundreds?) of rejection slips. We praise the resilience of others (think of J. K. Rowling writing in that Edinburgh café, shivering as she fumbled open yet another envelope of bad news), but with Enid Blyton her blinkered refusal to give in and go away is seen by some as rather sinister. Publishers who tried to reject her early stories and poems about flower fairies and thistledown were simply treated to more of the same. In the end most of them succumbed – particularly when they got a whiff of the sales.

Enid understood better than anyone the importance of tending her brand. She ensured her wartime divorce (and swift remarriage) was kept secret from the world by swapping husbands (and her married name) while everyone’s attention was elsewhere. After the war was over she carried on as though nothing had changed, except the children’s ‘daddy’ was no longer a man in uniform, he was a doctor called Kenneth. Gillian and Imogen are still there in the family photos, stroking kittens and riding horses, but it was now Enid and twinkly Dr Kenneth Darrell Waters who were looking on fondly. The change of name didn’t matter, because Enid was never Mrs Pollock or Mrs Darrell Waters anyway – not to the world and its children. She was ‘Miss Blyton’. And throughout a life of hectic industry Enid kept her famous signature, marking every book with its comfortingly rounded initial ‘E’, its soft but perky pen-work and the firm double underline a binding promise of extra helpings of adventure and fun.

Enid Blyton may have said that her stories and their settings emerged from her subconscious, but Swanage, the Isle of Purbeck and its fields and moors, farmhouses, beaches, coves and caves are what fed her imagination. I am slipping and skidding along the coastal path that leads from Swanage to the village of Studland, battered by the ferocious wind, scoured by sleet, hood up, head down, wondering what would happen if I just keeled over into a ditch – and how long it would take before I was found. I am the only fool on the path. The way is narrow and glutinous with a cold, deep, clutching mud. In places, especially where the path is steep, clumps of blackthorn are crowding close, the early blossom clinging in misery to the branches, but at least the bushes provide a veneer of shelter. Once I reach the top, the wind rages over the open fields and I have to fight my way to the headland and the view of Old Harry Rocks – three collapsed chalky arches rising from the sea. There are a couple of people here, whooping into the gale, and then, emerging out of the snow (the temperature is dropping) a party of teenagers comes into view, one bouncing a football, some on their phones, laughing and sauntering along as if they were on Oxford Street.

It is exhilarating here, at Britain’s southern edge, leaning into the wind at the top of the giddy cliffs, watching the waves heave and thrash against Old Harry Rocks. A seagull comes screaming up from the sea and is flung inland. Everything – the deadly waves, the torn trees, the shrieking people – feels wild and unfettered. Unhinged even. Do not imagine for a second that Enid, for all her mimsy, would not have revelled in this mayhem. She loved a good thunderstorm. And even though Gillian thought her mother was essentially a shy person, she lived her life with passion and a whirling energy. Gillian’s sister Imogen, in her troubling ‘fragment’ of autobiography A Childhood at Green Hedges, published twenty years after her mother’s death, quotes her friend Diana Biggs:

Your parents came over for a drink and I remember walking into our drawing-room. Enid Blyton was sitting in that settee. It is over forty years ago, but … none of that has dimmed my first impression. She was incredibly vibrant, an absolutely vital person. Everyone else in the room sort of faded. It was just this incredible personality sitting on the settee …

So. Enid had energy and fire and immense creativity (measured by volume, at the very least). But what she did not have, it turns out, is the ability to bring specific landscapes to life. She is not, in that portentous phrase, ‘a writer of place’ – looking to portray with fine detail a well-loved meadow or clifftop walk – or indeed to take that meadow and transform it through her art into something that sparks with its own unique essence and fire. The simple fact is that Enid writes in archetypes (another word would be clichés). She had no interest in writing with evocative precision about specific places. It is certainly very hard to pin them down in her writings. I am criss-crossing the south-eastern tip of the Isle of Purbeck, from Swanage to Studland, via Old Harry Rocks and the Agglestone Rock, taking in Agglestone Cottage and the views from the moor over to Brownsea Island, and although I know (because I’ve been told) that Hill Cottage near the golf course (bought by Enid’s second husband Kenneth for £1 in 1951) is the model for Agglestone Cottage, and that George found Timmy (found him!) on the moor above Kirrin Cottage, and that Brownsea Island was transformed into Whispering (or Wailing) Island in Five Have a Mystery to Solve, there really is almost no clue in most of her books. What you will find is an ‘old’ farmhouse and a ‘blue’ sea and a ‘lovely’ bay.

The path from Old Harry Rocks heads north and east along the clifftop, following the coast, through stretches of flowering gorse and scraps of woodland, and into the village of Studland. Enid and Kenneth started taking their holidays here from 1960 onwards, abandoning the Grand in Swanage in favour of the Knoll House Hotel. It’s possible that Enid wanted to be more secluded (she was very famous by now), or that she wanted to be near Kenneth’s golf course (she learned late, but could whip through three rounds in a day). The price wouldn’t have bothered her. Kenneth, said Enid’s daughter Imogen, was not slow to take advantage of his and Enid’s joint account, and ‘once he had acquired the taste for spending money, he began to spend a great deal’. But only on the big things (jewellery and a chauffeur for Enid, a Rolls-Royce and a Bentley); he would also hoard paperclips and hand-deliver any letter he could. Enid didn’t care either way. She found it funny. Anyway, people seem to agree that Kenneth was a good husband for Enid: an old-school doctor, devoted, somewhat rigid, energetic, enjoyed a simple joke, conservative, busy and serious, rather deaf (which didn’t help his temper, although Enid’s perfect diction was a boon), and resolutely middle-brow in his cultural tastes. At one time there was talk of Enid becoming a professional musician (or at least her father had hoped so) and she was also a talented artist, but all of that seems to have faded away in the Kenneth years.

The Knoll House Hotel is low, friendly and soothing – and I can see why Enid was drawn to it. By 1960 she was already suffering from the Alzheimer’s that led to her death in November 1968, aged just seventy-one. Certainly her output was dropping: she wrote the last Famous Five book in 1963, published three books in 1964, and then fell uneasily silent. As Barbara Stoney writes in her biography, ‘as time went by she found it increasingly difficult to concentrate long enough to write coherently or to stop her fantasy world from spinning over into the reality of her day-to-day life’. She had always had a fear of losing control – of what might be lurking in her memories, or in the depths of her subconscious – and these years must have been terrifying.

But I like to think she found pleasure at the Knoll. She used to sit in the dining room watching the children. There are gorgeous views from some of the public rooms (and her preferred bedroom at the back), over Scots pines and a weather-worn tennis court down to the sparkling bay. There’s a brass bust of Enid in an alcove at the hotel (they are very proud of the connection) as well as one of Winston Churchill. I wonder if the Churchill bust was here when Enid was staying. Her first husband, Hugh Pollock, oversaw the production of Churchill’s monumental The World Crisis (later The Great War) in the 1930s, the two of them spending long days locked away at Chartwell, editing and rewriting, tucking into the brandy and cigars. It must have been a thrilling experience for Hugh (he revered Churchill), but another turbo-boost to his alcoholism. He drank heavily for most of his and Enid’s marriage, although he tried to hide it from her. And she was eager to be deceived, even if her diaries are full of his illnesses and indispositions. When he fell seriously ill in 1938 Enid found a great cache of empty bottles in their cellar – his secret hoard, brooding under their home, like a long-forgotten treasure trove in an ancient dungeon, just waiting to be discovered. Enid had plenty of secrets of her own, but she hated other people’s.

It is troubling to think of Enid in these later years, her mind skimming between the daily routine and her ‘fantasy world’. She had always dreaded what might be waiting for her, once her defences were down. It’s no wonder there are so many caves and secret passageways and hidden tunnels in her books. It’s right there in Five on a Treasure Island, after the enormous storm has upended everything: ‘There was something else out on the sea by the rocks beside the waves – something dark, something big, something that seemed to lurch out of the waves and settle down again.’

Once, everything flowed so easily for Enid; the boundary connecting her ‘under-mind’, as she called it, was porous and thin; and she only had to peek inside, hold the door ajar, and her stories (her safe, jolly stories) would slip out and arrange themselves on the page. But now the doors were wide open and dark things were stirring. I don’t think she was hiding anything genuinely horrifying (or even criminal) from herself. I think it is more likely that she was agonized by the gap between the way she wanted to be, the way, in fact, the best characters in her story books always behaved – Christian, kind, loving, open, generous – and the way she had been in her life. Or maybe she found it hard to reconcile what she thought and felt and wanted (her ferocious drive, her self-absorbed writing life) with the way she imagined she should behave. Perhaps she was tormented by how far she had fallen short of her own absurd and impossibly perfect brand.

Enid preferred to write her books, and live her life, on the surface. And to keep things vague. But even if it is hard to locate specific places, here in the Isle of Purbeck, the truth is that everything inside an Enid Blyton book is instantly recognizable. She takes the world and makes it less confusing, kneading her ingredients into something manageable, safe, tidy and above all familiar. Even when she is leading us up a Faraway Tree to a land of saucepan men and irritated polar bears, all of these things have their untroubling place – and the children are free to go home once the fun is over. Perhaps, on second thoughts, Enid really did manage to capture the essence of the Isle of Purbeck. And all those people who have moved here, looking for a lost land of unlocked front doors, well-tended hedgerows and a steam train panting in a siding at the heart of an English village – perhaps it is Enid Blyton who has drawn them here. Just how deep does her influence run? There was a time, not so long ago, when it would have been hard to find a single child in Britain who had not read (or been read) at least one Blyton book, and suckled themselves to sleep on her warm, tender, infinitely reassuring words. We are all, as she so often said, her children. And she is our storyteller.

Here’s Julian (the oldest of the four children) in Five Have a Mystery to Solve: ‘I somehow feel more English for having seen those Dorset fields, surrounded by hedges, basking in the sun.’ To be clear, Enid Blyton didn’t invent that particular image of Englishness – you might as well credit P. G. Wodehouse or John Constable or the Acts of Enclosure – but she certainly spread it far and wide. And although I am sure it is true, as Enid’s daughter Gillian said, that ‘every nationality enjoyed them [her books] just as much as the English children did’, that only goes to show that it is not just the English who are in thrall to the vision – that wistful English vision, polished over the years – of pure, unsullied village life, of George Orwell’s ‘old maids biking to Holy Communion through the mists of the autumn mornings’. Orwell wrote much more than that, of course, in his attempt to define Englishness (‘the diversity of it, the chaos!’), and even in the same paragraph there is plenty about ‘clogs in the Lancashire mill towns’ and ‘queues outside the Labour exchanges’. But it is the misty mornings that linger. Perhaps they get to us all in the end. And the fact is, these things really do exist – ancient water meadows, thistledown drifting in country lanes, cheery publicans, apple-choked orchards and the soft silence of village greens fading into the twilight – and even now they are here, right here, in the Isle of Purbeck. However much the frozen wind may howl. And whether or not you are all of a sudden shaken by an irresistible urge (a spasm of fury from the world outside this muffling cocoon) to rage and stamp all over someone’s immaculate front lawn. It is here – and everything else will pass. Softly now. Just come on in. It’s all lovely. Quite, quite lovely.

When I throw open the curtains in my top-floor room at the Grand the next morning, I am met by a searing blaze of sunshine. The wind has gone. The sky is a tentative, early morning blue, rinsed and in recovery from yesterday’s storms. The sea is flat, tense even (and also, as Enid could tell us, undeniably blue). There’s a ginger cat sitting on the sleek green lawn just below my window, where Enid once walked (the world is full of colour this fine day), and as I watch it stretches and strolls with its tail high towards the steps that lead to the Grand’s private beach. It is a day to be up and doing. Adventures are around the corner. My wife, Anna, has arrived and I turn, the curtains still in my hands, and half-shout, ‘Look at this weather. It’s LOVELY!’ Ah, the salty tang of the fresh Swanage air.

Enid moved her Swanage base from the Grosvenor Hotel to the Grand in 1952 and kept on coming until she discovered Studland’s Knoll House Hotel in 1960. The holidays of her most prolific years were spent here in the Grand, swimming and playing golf with Dr Kenneth now that her children had left for their universities. In essence, the place probably hasn’t changed much since. The great central staircase, now quietly suffocating under the weight of its own dusky blue carpet, was presumably here; the pictures, of sailing ships and sunny seas and storms, look ageless; the views from the back, over the sea, are of course the same (if you squint and wear blinkers to block out some more recent developments); but I’m not so sure about the insinuatingly bland background music that chases us from bedroom to breakfast. It wouldn’t have bothered Kenneth (if he listened to music at all he liked it simple and LOUD), but I can imagine Enid telling someone sharply to turn it off.

I feel sure that Enid enjoyed her journey along Britain’s social scale. She was often accused of being class-obsessed (or rather, for unthinkingly writing about families with cooks and gardeners and tuck boxes), but I’m not convinced she was any more preoccupied with class than other writers of her time, whatever their background. That’s just the way it was – and is. In fact, there was an awful lot of snobbery about Enid Blyton. Sure, she lived in a large house in the country and wore tweeds, she kept a chauffeur and spoke with a honeyed, nursery nanny accent, and she took her holidays at the Grand in Swanage (although don’t get your hopes up, it’s not that grand …), but everyone knew, or at least those awful English people who care so much about such things knew, and they made sure that everyone else knew, that she had been born in a small two-bedroom flat above a shop in south-east London (No. 354 Lordship Lane, East Dulwich, if you’d like to go and pay homage) and she wasn’t the blue-blooded grande dame of Beaconsfield that she was never even pretending to be. You see, Enid got it in the neck from every kind of snob: intellectual, literary, high culture, inverted, Oxbridge, working class, the middle don’t-get-above-yourself class, anti-women snobs, anti-success snobs, and all the other dreary, run-of-the-mill, ‘where-do-you-come-from?’ snob snobs.

She didn’t seem to care. Of course it grieved her that the BBC had a secret policy to keep her from their programmes. She also found it easier, as the years went by, to define herself as solely a children’s writer (although she had always wanted more and hoped one day to write for adults, even if, as seems likely, she had no talent for the task). But she was buoyed by Hugh and then Kenneth and found infinite reassurance in her clubs and readers and her all-conquering book sales.

And then there were the joys of Swanage, which we are keen to see on this extraordinary, unexpectedly bright day. More than that, it would be a relief to get away from the Grand’s busy conservatory breakfast room, which is in danger of being overwhelmed by an awkward, infectious silence, a familiar English embarrassment that fills and agitates the tense air (and even now is no doubt stifling hotel and B&B breakfast rooms across the land). I’m as susceptible to it as anyone. Knives scrape on plates; feet shuffle towards the buffet and back; uneasy, secretive whispers escape from the tables (‘full English?’; ‘looks like a nice day’; ‘did you bring the suncream?’; ‘more tea?’); and all the while the morning Mail’s crisp new pages crackle and softly fall, to the ‘tut’ and snort of its readers and even, just once, a plaintive moan of despair.

We leave in a hurry and head westwards along the coastal path from Swanage. We pass the Wellington Clock Tower, which once stood by London Bridge before it was dismantled and brought here, along with any number of London iron bollards and the actual façade of Swanage’s town hall (which came from a building in Cheapside). Nothing is quite what it seems. We skirt the lifeboat station (well supported by Enid in her day) and Peveril Point, site of many shipwrecks (and a naval battle between King Alfred and the Danes). The path runs through green fields, with the cliffs and the sea on our left. Banks of dark, bare thorn bushes keep us from the edge. Young teasels nod and bob in a slight breeze. There are larks overhead and when we stop to lie on a grassy bank a blackbird hops close and inspects us with an eager eye. I would be even happier if I could find some heather (you will remember that no Enid Blyton camping trip is complete without a bed of heather, gathered in armfuls and arranged under sleeping bags into soft, springy mattresses), but all I can see is yellow gorse and empty fields, cropped close by sheep.

There’s a mist gathering far out to sea, but no cloud in the sky. Below us, just over the thorns, the sea is whumping into the caves at the foot of the cliffs, the waves sucking and slapping at the rocks. When Celia Fiennes came here in the 1680s on one of her horseback tours around Britain, she – like Enid – became obsessed with the craggy shoreline and its caves:

At a place called Sea Cume [Seacombe] the rockes are so craggy and the creekes of land so many that the sea is very turbulent, there I pick’d shells and it being a spring-tide I saw the sea beat upon the rockes at least 20 yards with such a foame or froth, and at another place the rockes had so large a cavity and hollow that when the sea flowed in it runne almost round, and sounded like some hall or high arch.

None of this has changed, although the abundant glut of ‘very large and sweet’ ‘lobsters and crabs and shrimps’ that Celia noted (and devoured, ‘boyled in the sea water and scarce cold’) has taken a battering over the last three hyperactive centuries of unchecked consumption.

There are very few people about on this early spring day. We pass the occasional middle-aged couple and greet them with a wave of cheery recognition. A climber is letting himself slowly down the cliff, shouting to someone far below. A rescue helicopter appears noisily over the horizon and hovers, before disappearing back the way it came. We walk on, and at Dancing Ledge (an artificial swimming pool created in a cove when a schoolmaster dynamited the rocks so his pupils could enjoy a safer swim) we meet a man who runs ‘adventures’: climbing, sea kayaking, caving … Imagine living in a time when gunpowder was freely available – and anyone who wanted to rearrange the coastline could just crack on. It’s only 100 years ago. Enid came here often with Gillian and Imogen, and the place emerged straight onto the pages of First Term at Malory Towers (1946):

[It] had been hollowed out of a stretch of rocks, so that it had a nice, rocky, uneven bottom. Seaweed grew at the sides, and sometimes the rocky bed of the pool felt a little slimy. But the sea swept into the big, natural pool each day, filled it, and made lovely waves all across it.

Yes, it’s here all right. The ‘adventure man’ is urging us huskily to join him in climbing the cliffs today or, failing that, to come back tomorrow and get involved in some sea-caving. He seems especially keen to convince my wife. Apparently it’s quite hard work, but well worth it. And not at all dangerous. Oh no.

I am sure Enid would have tried it. She had a love of nature and adventure instilled in her by her father, she always said, and it was partly his restless influence (as well as a horror of turning into her mother, a bored, bereft housewife) that drove her on. Her father, Thomas, was a cutlery salesman from Sheffield when he married Theresa Mary Harrison. Enid, their first child, was born in 1897. Two boys followed rapidly – Hanly and Carey – by which time the family was living in a semi-detached house with a sizeable garden in Beckenham, Kent. Enid said that her father gave her a small patch of this garden and, as she told her young readers in The Story of My Life:

Nobody knew how much I loved it. Well, you might know, perhaps, because some of you feel exactly the same about such things as I felt. You don’t tell anyone at all, you just think about them and hug them to yourself.

Enid was a lonely, secretive child, most likely. She didn’t get on with her mother and blamed her when Thomas went to live with another woman, leaving Theresa to bring up the three children. Her mother, she wrote later, ‘was not very fond of animals’, the sure-fire signifier in Enid’s fiction that someone was a wrong ’un. Enid was twelve when her father left home for good. On the night before he left, as he and Theresa screamed and raged at each other, Enid tried to drown out the noise by telling stories to little Hanly and Carey. And that, as any amateur psychologist could tell you, was what she continued to do for the rest of her life. Drown out the noise with her stories.

This is not to say that she had a miserable childhood. She had friends. She was offensively successful at school (head girl for her final two years; tennis champion; captain of the lacrosse team; recipient of endless academic prizes). But it is also true that none of her friends knew that her father had left home, and when Enid herself was given the chance to leave (in 1916, aged nineteen, to work on a farm and then at a kindergarten, launching herself on a career of teaching), she hardly ever saw her family again. She was twenty-three when her father died of a stroke at his new home (and not out boating on the Thames, as she was told, to spare her hearing about his new lover). Although she had seen a bit of him over the years, she didn’t go to his funeral.

So maybe now is the moment to take a longer look at the elephant in the room (or drag Jumbo out of the toy cupboard). There is a popular view of Enid Blyton, entirely at odds with her own carefully tended self-image, that she was an unpleasant, cold-hearted, cruel woman and a neglectful, spiteful mother. As her daughter Imogen put it on the very first page of her ‘fragment’ of autobiography: ‘Which of us was the more emotionally crippled I cannot tell.’

But it goes deeper. There are plenty of people who are consumed with a visceral loathing of Enid Blyton – the author, the person – and all her works. This includes many librarians (whose lives have been devoted to the joys of reading), who would like to build a funeral pyre of every last book that Enid ever wrote, hose it down with petrol and toss on the flaming match. She has been denounced by fellow writers, clerics, critics, parents and politicians. Her plotlines are all the same, they say. The characters are wooden. The language is lumpen. Everything she ever created is suffused with a ghastly middle-class morality, a small-minded insularity, a twee, limping, class-ridden, racist, sexist, smug, sanctimonious sentimentality. Her stories are vicious, bullying, shallow, preposterous, predictable, unfunny, patronizing. They are lost in a never-never land of happy families, boarding school tuck shops, forelock-tugging, cap-doffing retainers and creepy elves. Goddammit, they’re childish.

Here’s the critic Colin Welch writing in Encounter magazine in 1958, in an article called ‘This Insipid Doll’, thrashing about in impotent rage because his children loved Noddy and would accept nothing else for their bedtime story:

If Noddy is ‘like the children themselves’ [Enid’s stated aim], ‘it is the most unpleasant child that he most resembles. He is querulous, irritable, and humourless. In this witless, spiritless, snivelling, sneaking doll the children of England are expected to find themselves reflected.

Almost as much of Colin Welch’s fury seemed to be aimed at the author, Enid Blyton, as it was at her creation, little Noddy. What especially enraged him (apart from having to read Noddy books to his children every night) was that he thought Enid Blyton was writing down to her audience: ‘by putting everything within the reach of the child’s mind, they cripple it … Enid Blyton is the first successful writer of children’s books to write beneath her audience’. He writes longingly of the Winnie the Pooh books, Alice in Wonderland and Edward Lear, books he could enjoy reading (stretching, wondrous, magical books) as much as his children would enjoy hearing them. But he misses the point, because Enid’s books were written for children. She was quite clear on this point, especially as the grown-up criticism grew: she couldn’t care less what adults thought. They could go whistle, taking their harsh and confusing adult world with them. It is probably why Enid set up so many clubs. Just for her and ‘her’ children. There must have been hundreds of thousands of children in the Famous Five Club: collecting silver foil to raise money for charity, writing to Enid, sharing their hopes and dreams.

Are the works of Enid Blyton a gateway drug, luring young children into the joys of reading, before guiding them on to better and brighter things? Or is there a danger that the youthful Blyton aficionado will get trapped in her two-dimensional world, mainlining monosyllables and addicted to easy thrills? Thirty years later you’ll find them slumped and drooling on a sofa, watching Friends on an eternal Netflix loop.

Enid herself set out to write for every age group. You could grow up with Blyton, she proclaimed, from Mister Twiddle to the Famous Five via Noddy and St Clare’s. But surely even in her headier moments she didn’t expect children to read only her works? I certainly had my fill of Noddy growing up (and not just the books, but the jigsaw puzzles and clockwork cars and pert pink toothpaste). And I remember the Bible stories and dipping into the Secret Seven. But it was the Famous Five books that obsessed me – Mystery Moor, Smuggler’s Top, Finniston Farm – right up to the day I arrived at my new school, aged eight, clutching my absolute favourite, Five Go Adventuring Again (you know, the one with the secret passage and the bearded tutor, Mr Roland, whom Timmy bites on the ankle, because he knows, doesn’t he, that Roland’s a bad ’un – he has a beard, for God’s sake! – and is plotting to steal Uncle Quentin’s inventions), and I was sneered at by one of the older boys. ‘What a baby – reading Enid Blyton,’ he scoffed. ‘Everyone’s a critic,’ I must have sobbed, as I stuffed the book back down deep into my bag, never to be opened again. Or not until I read it to my own children. Ha! Take that, school bully.

But was my emotional and mental development stunted by my love of Blyton? The BBC was quite clear that it would have been – and seems to have carried out a policy of no-platforming from the very earliest days. In 1938 Enid’s first husband, Hugh Pollock, even wrote to the head of the BBC, John Reith (whom he knew slightly) asking if he could put in a good word for Enid. It didn’t work. An internal BBC memo from 1940 was brutal in its reasons for rejecting one of her submissions, ‘The Monkey and the Barrel Organ’: ‘This not really good enough. Very little happens and the dialogue is so stilted and long-winded … It really is odd to think that this woman is a best-seller. It is all such very small beer.’

In 1949 a BBC producer called Lionel Gamlin wrote to Enid Blyton asking if she would be happy to be interviewed for one of his programmes. He must have been startled by the reply:

Dear Mr Gamlin

Thank you for your nice letter. It all sounds very interesting – but I ought to warn you of something you obviously don’t know, but which has been well-known in the literary and publishing world for some time – I and my stories are completely banned by the B.B.C. as far as children are concerned – not one story has ever been broadcast, and, so it is said, not one ever will be.

She suggested that Lionel Gamlin seek confirmation from his bosses, which he must have done because in his next letter to Enid he glosses over his invitation and says he regrets that she felt unable to contribute to the programme. Enid set him straight: ‘I think, if you don’t mind, I must just put it on record that I did not refuse to appear in your Autograph Album series, but, on the contrary, would have been delighted to do so.’

But the ban continued. In November 1954, with Enid at the height of her fame, the BBC show Woman’s Hour came under immense pressure from its listeners to include an interview with Blyton, or at least broadcast some of her stories. The editor, Janet Quigley, wrote to Jean Sutcliffe of the Schools Department, asking for her help in beating back the BBC producers who thought that ‘we are being rather stuffy and dictatorial in not allowing listeners to hear somebody whose name is a household word’.

Jean Sutcliffe’s reply is a masterclass in old-school elitism. She says that if the invitation to Enid Blyton is ‘simply to meet her’ and ask her to give her views on ‘Horror comics or Hats … then no harm could be done’. But if she is ‘allowed to lay down the law on … writing for children – unchallenged … the BBC becomes just another victim of the amazing advertising campaign which has raised this competent and tenacious second-rater to such astronomical heights of success’. She goes on: ‘It is because of all this that I think people in positions like ours have every right to exercise our judgement in deciding who shall utter unchallenged on certain subjects.’

In other words, Enid could come on to the BBC to talk about hats and horror comics, but under no circumstances would she be allowed to discuss her own writing ‘unchallenged’. And nor would the BBC be dramatizing any of her stories. These days we’d say that Enid Blyton was the victim of a culture war. Or maybe standards have slipped. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the BBC finally relented with the release of the Noddy videos (‘Milk-o-o-o’).

Even after her death, the BBC hadn’t finished with Enid. They’d banned her books; now they trashed her character. In Enid, a 2009 dramatization of her life, they had Helena Bonham Carter play her in full-on Bellatrix Lestrange mode: an ice-cold witch who’d rather hug a fox terrier than pick up her own crying baby; who threatens to dismiss her chauffeur for coughing and then goes back to gloating over another bundle of fan mail; who drives her sweet and loving husband Hugh to drink (it’s Matthew Macfadyen playing Hugh, his whipped-spaniel eyes milking every vicious slight from his wife); and who warmly (falsely!) welcomes the children who’ve won the chance to meet her by ushering them into her study for home-made cakes and stories (while her own two little girls, whom she hardly ever talks to, look on in misery through the bars of the banisters).

As Hugh slurs at one point: ‘the only reason your fans adore you is because they don’t actually know you’. And then he goes to bury Bobs the terrier in the garden while she stares at him with cold contempt from her study window before rattling out another cloying story on her infernal typewriter about how happy ‘Bobs’ is with his daddy and mummy in their sham of a rural idyll.

You can see why the film-makers did it. It’s a lip-smacking story: iconic children’s author, twee moralist and the epitome of old-school England turns out to be a hypocritical bastard. And it has helped shape what most of us think we know about Enid Blyton. The main source was presumably Imogen’s book, A Childhood at Green Hedges: A Fragment of Autobiography by Enid Blyton’s Daughter, although Barbara Stoney’s more measured biography certainly includes some juicy plums, and if you want to delve deeper there’s also Starlight by Ida Pollock, Hugh’s heroic second wife (also a prolific writer, but of romantic fiction).

Anyway, it’s time to lift the stone. Yes, she really did beat her children, usually with the back of a hairbrush. She even beat Imogen once for laughing too much with one of the nannies. You could say that child-beating was not unusual in those days, but Enid was also accused by Imogen of emotional neglect: ‘Every week without fail, throughout my whole boarding-school career, my mother wrote to me, short friendly letters, much the same as the ones she wrote to her fans.’

Enid loved her fan clubs and was nourished by the hundreds of thousands of letters she received. But she also loved her own children, I’m sure of that. The awful truth is that she may have found Gillian easier than Imogen. Certainly that’s what Imogen thought: ‘my sister’s more generous and outgoing personality has always been an easier one to relate to than my suspicious, defensive and often downright rude one.’

Barbara Stoney and others have decided that Enid was essentially a child herself, hence her astounding facility for getting into children’s minds. Stoney wrote that when Enid was finding it hard to conceive a child, her doctor found she had the ovaries of a twelve-year-old. This rather creepy theorizing has led many to decide that Enid was emotionally frozen at the moment when her father left her mother. She certainly loved practical jokes, because this is how she passed the time on 17 January 1926: ‘Hugh and I threw snowballs at people walking below. It was such fun. Sewed till bed.’ But, no, she did not have the mind of a twelve-year-old.

We are also told that she never took in any child refugees during the war, and even when her friend, Dorothy Richards, asked her to put up some people who had been bombed out of London, she gave them shelter for a week and then threw them out because they were getting in the way of her writing. I think we can agree she was no Angela Lansbury in Bedknobs and Broomsticks, although she did take in a young maid fleeing Austria in 1939, and they became firm friends. She also ditched most of her friends when she became famous, ignored her brothers as much as she could, and cut off her mother (refusing to send her money and missing her funeral). Years later, as Enid slipped into pre-senile dementia, and even though her mother had been dead for years, she tried, painfully and repeatedly, to go and see her.

So, yes, she lied to others (and to herself) and there were parts of her life that she worked hard to forget. She could be arrogant (although which writer isn’t, living at the nexus of fantasy and self-doubt?). She had at least one affair, not that it should matter to anyone other than Hugh – but this is squeaky-clean Enid Blyton we are talking about, so of course there’s a prurient interest.

But that was just the warm-up, because here is a Top Ten of Enid Blyton Accusations (with a bonus at the end):

1. She really was a terrible mother

Here’s Imogen:

On Saturday mornings, my sister and I would go down to the lounge to collect our pocket money … It was on one of these occasions … that I came upon a new piece of knowledge. Something made me realize that this woman with dark curly hair and brown eyes … who paid me just as she paid the staff … was also my mother. By this time I had met mothers in stories that were read to me, Enid Blyton stories included, and I knew that a mother bore a special relationship to her child, from which others were excluded. In my case the pieces of the puzzle failed to fit together. There was no special relationship. There was scarcely a relationship at all.

There was a time when British middle-class parents were quite capable of neglecting their children. Seeing them just once a day to bid them goodnight. Sending them to boarding schools. I imagine Enid hoped for more – except she was also just so busy. She seems to have wanted to cram all her mothering moments into her Swanage holidays and the brief hour before dinner. It’s worth knowing that Gillian said that she talked with Enid ‘freely from early childhood’.

2. But she pretended to be the perfect mother

Imogen: ‘There is a well-established myth that my mother read frequently to my sister and myself, trying out her stories on us, her own small critics. This is quite untrue. I can only remember her reading one book to me …’

And Enid: ‘Gillian and Imogen read every book I write, usually before it goes to my publishers. Their favourites have always been your favourites.’

And Gillian: ‘I used to read chapters of her latest book hot from the typewriter after school, impatient for the next day’s instalment.’

3. She was vicious

Enid asked Hugh to take the blame for the breakdown of their marriage because she thought news of a divorce would be disastrous for her reputation. In return, she promised Hugh full access to their children, Gillian and Imogen. She broke this promise and Hugh never saw his children again.

We don’t know what was agreed, but this sounds right. It’s true that poor Hugh (alcoholic, paranoid and adrift) seems at one point to have decided that his children were better off without him. Time drifted. Also, there’s something undeniably absent about Hugh. Ida describes how when Alistair, Hugh’s son from his first marriage, wrote to let him know he was getting married and ask him to the wedding, Hugh contrived not to go – and possibly never even contacted him.

4. And she was spiteful

Here’s Imogen: ‘I remember one remark she made before a meal in the dining-room to my stepfather. “I do dislike people with inferiority complexes. Don’t you, Kenneth?” When he had made the required affirmative answer, she continued with her superb timing. “Don’t you think that Imogen has a dreadful inferiority complex?”’

Imogen’s book is a howl of pain. She writes with scrupulous honesty about her feelings and memories – and a strange air of judicious detachment (‘I read many Enid Blyton books …’). Or maybe she’s just numb. But it is painful to read; and contrasts starkly with Gillian’s bland, amiable memories. In her afterword to Imogen’s book, Gillian writes: ‘It is strange to see one’s childhood through the eyes of a sister: people, events, emotions charged with a different significance; reinterpreted.’ And she finishes: ‘I and my children are very happy to have this record of a part of our family history and I think that my mother would have been delighted that it had been written by her daughter, Imogen.’ Which is an extraordinarily diplomatic response to Imogen’s raging memoirs. Her mother would have been ‘delighted’? Really? It sounds to me like she’s handling Imogen with kid gloves.

5. And she was vindictive

After the war, when Hugh tried to find employment at his old firm, George Newnes, Enid is said to have blocked him. As his boss said: ‘In the end, Enid is more important to us than you are.’ Many other publishers closed their doors to Hugh.

Here’s Ida Pollock: ‘It soon became clear that the Blyton “camp” had started to set in motion a serious smear campaign. Hugh Pollock, the story went, was an adulterous alcoholic who had shamelessly betrayed, then cold-bloodedly abandoned his brilliant and long-suffering wife.’

Was this Enid herself at work? Possibly, but publishers are an unsentimental bunch. Not to mention the most appalling gossips.

6. But it gets worse

Hugh and Ida’s daughter, Rosemary (Ba) suffered from terrifying asthma attacks, sometimes only surviving on ‘a cocktail of drugs’. Hugh and Ida were bankrupt (he couldn’t get any work …), so Ida’s friend Dora (an actress, who relished a scene) went to see Enid at Green Hedges to ask if she would include Ba in the Trust that Hugh had set up for Gillian and Imogen – so they could afford to buy Ba some medicine.

Here’s Ida:

Told this woman on the doorstep was a relation of mine Enid may have felt a degree of curiosity, or perhaps she was drawn by the tenuous link with Hugh. Anyway, Dora was admitted. To begin with, I think, she was polite and conciliatory. Surely, she suggested, it should be possible to open up the Trust – after all, Hugh had established it for the security of his children. And his little girl, Rosemary, was very unwell.

‘Definitely not’, said Enid – or words to that effect. The Trust had been set up for Gillian and Imogen, and she had their interests to consider. But now, Dora pointed out, Hugh had another daughter. Everyone was worried about Rosemary – alias Ba – and surely …

‘I don’t care’, said Enid Blyton, ‘if the child dies.’

According to Ida, Enid regretted what she had said and ‘eventually’ opened the Trust. But, still … what kind of person says that? Assuming that is what she said.

7. Her stories are unbearably sexist

What with Anne always doing the dishes and making the sandwiches and waving Dick and Julian (and George, on sufferance) off on their adventures. The mothers stay at home and smile a lot. The fathers go out to work. Yes, these books are sexist.

It’s a small thing, but there’s always George, everyone’s favourite character, the girl who’d rather be a boy. Reinforcing stereotypes, sure, but she has such fierce honesty. She is based on Enid herself.

8. Her stories are undeniably racist

Exhibit ‘A’: Here Comes Noddy Again, written in 1951. In which our little hero gives a lift to an ill-mannered golliwog, who leads him to the dark woods and ‘three black faces suddenly appeared in the light of the car’s lamps’ and Noddy is mugged, his clothes and car stolen. Enid insisted that there were more bad teddy bears in her stories than bad golliwogs – and that they’re ‘merely lovable black toys, not Negroes [sic]’.

Some years after Enid’s death, the golliwogs in her books were all replaced by goblins – and it’s certainly easier to excuse Enid than it is anyone who agitates, today, for their reinstatement.

9. Her stories are maddeningly middle-class

Indeed they are. All the villains in the Famous Five stories have rough voices and beards, the foreigners are wrong ’uns to a man, and the circus folk and gypsies are, at best, a mixed bunch. Meanwhile, the cooks are all apple-cheeked and smiling, the gardeners tip their caps and tell the young scamps to run along, and the police protect the property interests of the privileged.

Maybe it’s best to read Enid Blyton’s books as science fiction. Or even pause and wonder why the (much worse, but also of-its-time) sexism and xenophobia on show in the Biggles books or John Buchan are more often brushed aside with an indulgent chuckle.

10. And she couldn’t bloody write

She may have written too much too fast, but don’t pretend that her stories aren’t some of the most accessible, immersive, utterly thrilling works that have ever been created. For children. I have reread dozens of her books recently and although they follow a grimly predictable (reassuring) pattern, and her incessant use of the words ‘lovely’ and ‘blue’ is irritating, I also quietly wept (yes, I did) when Elizabeth, The Naughtiest Girl in the School, is redeemed and her best instincts are coaxed into life. More often than not, Enid Blyton writes with addictive verve and JOY – and she knew exactly how to grip her audience.

11. She threatened to fire a chauffeur for coughing …

… while staring at him with breathtaking malignancy.

Really though, did she? As they write with Fargo-esque candour at the beginning of the BBC’s Enid: ‘The following drama is based on the lives of real people. Some scenes have been invented and some events conflated for the purposes of the narrative.’

It is worth asking how well any of us would fare under this detail of scrutiny. And why Enid Blyton was (and is) on the kicking end of so much virulent criticism. It couldn’t be because she’s a woman, could it? A wildly successful businesswoman, who dragged herself up from modest beginnings to become the world’s bestselling children’s author. Negotiating her own, highly favourable author deals. Planning and executing the roll-out of innumerable brands. This should have made her a hero to many, but she was also culturally and politically conservative and, crucially – as the new century took hold – a prominent symbol of the ‘nanny knows best’ Britain, with her hectoring morality lessons and smothering, Edwardian aspirations. As the country changed around her, most people moved on from Enid. But there were also plenty of others who wondered if there wasn’t more to her story than the one she was so keen to tell about herself. They were undeniably gratified to learn that there was.

When I was studying English literature at university in the 1980s, we were asked to read Kingsley Amis’s Jake’s Thing, a book about a middle-aged man who’s worried about his non-functioning penis (his ‘thing’, you see). One of my fellow students walked out within five minutes of the start of the first lecture, because she found the views of Kingsley Amis (the man, not the author) obnoxious and didn’t want to hear what he might have put into his (probably obnoxious) book. Enid would have been the first to agree that there was an indissoluble connection between a writer’s life and character and their work:

As you can imagine, we are a happy little family. I could not possibly write a single good book for children if I were not happy with my family, or if I didn’t put them first and foremost. How could I write good books for children if I didn’t care about my own? You wouldn’t like my books, if I were that kind of mother!

And – flipping it over: ‘You cannot help knowing, too, whether you would like the writer or not, once you have read two or three of his books.’

But we were being told that there was no link between the biographical details of an author and what she puts into her work. It doesn’t matter that Coleridge consumed opium by the jar or that Ezra Pound was a fascist – just look at what they wrote and ignore their lives. Their words should stand on their own.

I seem to remember that the philosophical foundation for this was a book by a man called Stanley Fish, and our lecturer excitedly pointed out that in chapter two of Jake’s Thing, Jake gets a sum wrong when counting out some change in a shop: so Jake cannot possibly be Kingsley Amis. And anything that Jake says (however crude and unpleasant – and there was plenty) is not the view of the author, Kingsley Amis, but only of his character, Jake. What I wanted to ask (but didn’t dare) was that if Jake’s pustular outpourings were not the same as Kingsley Amis’s, then how come you could read more or less the same stuff in Amis’s gleefully inflammatory journalism? And anyway, Kingsley Amis was a notorious drunk, so he was bound to have got his sums wrong. (Incidentally, Kingsley Amis’s suggested cure for the very worst of hangovers was a ‘brisk fuck’ – and I can easily imagine that waking up with a sore head to find a sour-breathed Kingsley humping and puffing on top of you would be enough to get anyone out of bed in double quick time and running for the shower, although it seems optimistic of Kingsley to think that he could have offered this service to everyone.)

We all know that not every (or any) character in an author’s books necessarily reflects her own views, but I think Enid’s deeper point is also true: we can’t help knowing if we’d like an author after reading a couple of her books – and it makes me realize that I do like Enid Blyton. Kingsley too (and his jokes are better), but neither of them makes it especially easy.