RIGHTS, NOT SYMPATHY

All of this must be said, and said repeatedly; otherwise, those Canadians who do not think of themselves as Aboriginal will go on misleading themselves as to what is now happening. They will misread the movement of history, the meaning of the events we are all living, the possibility of a reimagined narrative.

What is happening today is not about guilt or sympathy or failure. It is not about a romantic view of the past. Nor about old ways versus new ways. Nor about propping up people who can’t make it on their own.

What we face is a simple matter of rights – of citizens’ rights that are still being denied to indigenous peoples. It is a matter of rebuilding relationships central to the creation of Canada and, equally important, to its continued existence. But there is more. We also face the possibility of those relationships opening up a more creative and accurate way of imagining ourselves. A different narrative.

Getting the narrative right is so important that I want to repeat the argument about what stands in the way. If we are not careful, informed and conscious, we can easily slip back into passive forms of sympathy when confronted with the suffering of First Nations children or poverty on reserves or family problems coming out of the destructive effects of the residential schools or failures in leadership. This is not an honest reaction. This is the modern shape of deeply ingrained attitudes going back to those old European-derived attitudes of superiority.

I have never heard of Aboriginal peoples seeking to be categorized as victims. I often feel that, when it comes to Aboriginal peoples, sympathy from outsiders is the new form of racism. It allows many of us to feel good about discounting their importance and the richness of their civilizations.

Sympathy is a way to deny our shared reality. Our shared responsibility. Sympathy obscures the central importance of rights.

If not sympathy, then what? In September 2013, in the Columbia River Basin, I listened to Kathryn Teneese, chair of the Ktunaxa Nation Council, explain that the first step is “recognition and acknowledgment.” Then we can work at our relationship “one step at a time – and gradually – find things we can do together.” In other words, “reconciliation” is not an event. It is not an apology, although an apology was necessary. And it is certainly not something so lacking in respect and dignity as sympathy. In any case, no solid relationship is possible so long as the Canadian government continues to rise in courtrooms and begin cases against the rights of Aboriginal nations by first arguing before the law that they do not exist as a people. This is our government. What could sympathy possibly mean if it is preceded by a denial of existence? In the same already mentioned conversation involving Lee Maracle and Michael Enright, Taiaiake Alfred argued that reconciliation can mean something if it starts from the position of restitution.

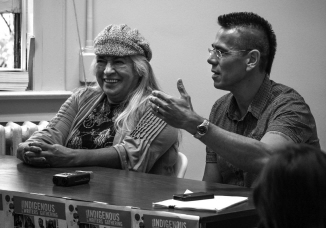

The poet, Lee Maracle, and the philosopher, Taiaiake Alfred. Two powerful voices. © MUSKRAT Magazine.

On the prairies there is an important piece of formal rhetoric: a question and an answer widely used in public meetings in order to remind everyone present of the reality in which they live.

“Who are the treaty people?”

“We are the treaty people.”

Treaties are signed by two parties. Both are bound by their signatures. Equally bound. Canada is built on and by the treaties, going right back to the first oral agreement made in the summer of 1609 between the Maliseet, the Montagnais, the Algonquin and the French on the low-tide sands of the Saguenay opposite Tadoussac. And Canada is built not only on the legal structure of the treaties, but equally on the cultural, ethical, human assumptions and commitments those treaties contain. These were and are the commitments of both indigenous peoples and newcomers entering into permanent community relationships. In fact, the treaties are in good part about newcomers entering into both the concept and the social reality of the indigenous circle. What does that mean?

Well, not all societies function in the same way. We are used to the European presumption that there may well be small, valid differences between serious civilizations – different social protocols, for example; different forms of politeness, of negotiation and so on. But these involve mere tweaks on the basic – there they are again – universal assumptions, all of which have been defined in Europe or in the Western tradition.

Powerful societies, imperial societies and their outlying imitators find it very difficult to admit that there can be fundamentally different models. That these other models not only work, but could be just as valid and might even have real advantages over the imperial model. And that while ultimate ideas of, for example, ethics may be shared across these models, how you get there, the use and avoidance of violence, and how you relate to the environment – to take just three examples – may be very different.

Platonist-dominated societies, like the European, see humans as the purpose of the planet and constantly seek conclusive answers that suit those humans. They lean toward the Manichaean. Lots of right versus wrong. Lots of moral determinism. This seems to go well with the idea of continual progress. A very linear idea. It leads down a path into such simple utilitarian assertions as “continual growth.” Again, very linear.

Asian societies have a variety of very different models. For most of the last couple of thousand years, methods such as the Confucian have outperformed Western approaches. For the last three hundred years the Western method has outperformed those of the East. The last two decades have seen a messy, often ugly but nevertheless powerful return of those Eastern theories. The West has done its best to pretend that China’s economic success, for example, is the result of its adopting Western methods. This simply isn’t true. Western technology has been used, but very little of Western theory. For better and for worse. The theory that has driven Chinese economics has far more to do with the elite version of Confucianism and the Chinese version of Communist initiative.

What about indigenous societies? Well, it could be argued that in the northern half of North America these tend to take a spatial or circular approach. What does that mean? Humans are part of the whole, not elevated above the place and its other inhabitants. And so humans see themselves from within existence. They do not gaze down upon it from above. This changes radically how things are conceived and therefore how things could be done. What does this mean in practical terms today?

Let’s take the example of the environment. Most of us agree that we are in some sort of environmental crisis, brought on in good part by a Western model that removes all effective philosophical brakes on human activity by interpreting the planet as our passive servant. Ours is a civilization built on a philosophy that involves no real brakes on movement. That has been a great strength. It accounts for many of our breakthroughs and our capacity to build in so many ways and to accumulate wealth. But it also accounts for the ease with which we slip into violence and, today, for our incapacity to take the environmental crisis seriously. Suddenly, our unflinching commitment to an idea of progress, which requires continual movement, begins to resemble a wilful child out of control – destructive and self-destructive. More and more people see ours as an old-fashioned, even dangerous theory. On the other hand, the northern indigenous philosophy sees the human as an integral part of the whole. Which means that we all have obligations to the other elements of existence. This could now be described as an appropriate, even as a highly contemporary philosophical, model for all of us. For a good explanation of this, read Richard Atleo’s Principles of Tsawalk, which I referred to earlier.

These very different civilizational concepts were shared to some extent by Europeans within Europe until the early seventeenth century. What’s more, the Europeans who came to the northern half of North America from 1600 on rapidly came to accept and live within the First Nations’ philosophical view. Why? Well, partly because these newcomers came from societies not yet dominated by “modern” linear concepts. What’s more, they were weaker than the indigenous peoples, dependent on them, partners with them. To put it simply: most things were organized around the First Nations’ point of view. And it worked. It made sense to most newcomers because they saw it as a way to survive. I wrote a great deal about this in A Fair Country.

And so, from the beginning, treaty negotiations and the treaties themselves reflected the indigenous world view. The Great Peace of Montreal (1701) and the Treaty of Niagara (1764) are two fundamental examples of this. Long after the colonial and then Canadian officials had ceased to believe in this indigenous approach to life, treaty negotiations and even treaties continued to reflect them. This was the way the later treaties were obtained: by pretending to believe in order to get the First Nations leaders to sign. Officials became increasingly hypocritical and cynical. No doubt an increasing number of the negotiators, representing Ottawa from the time of Confederation on, thought they could negotiate and sign in bad faith. In their minds there was only one model – European – and so these treaties were simple tools of power involving a transfer in ownership of land.

But the legal texts are just that. Legal commitments. And their meaning as complex, people-to-people treaties was reinforced by the government negotiators’ oral explanations of those texts during the negotiations, as well as by the Aboriginal negotiators’ explanations of their own understanding of the agreements being put in place. All of these elements were made clear in public before anything was signed. And so all parties agreed publicly that their relationships were to continue as always understood. These were permanent nation-to-nation agreements with obligations on both sides. To this the governmental negotiators committed the Crown legally, ethically and morally. And over the last four decades that reality has led the Supreme Court to rule repeatedly in favour of the Aboriginal position and against that of Ottawa, the provinces and the private sector.

Anyone sworn in as a Canadian citizen today or tomorrow inherits the full benefits and the full responsibilities – the obligations – of those treaties. British Columbia is only very marginally an exception to this reality, because it has signed fewer treaties. But the Douglas Treaties of 1850–1854 were among the most clearly tied to the Canadian tradition. And now British Columbia is slowly but surely entering into the treaty reality of Canada with such breakthroughs as the Nisga’a Treaty of 1999. The number of crucial Aboriginal victories at the Supreme Court coming out of that one province is remarkable.

But the slowness of this process opens the door to every negative possibility. Our governments continue to oppose any form of restitution and all real forms of reconciliation. Those who have been ignored and insulted for more than a century have every reason to lose patience. They are under no obligation to be patient. To lose yet another generation while Canada plays games. Increasingly, they have enough power to abandon patience as the primary tactical card of a minority under attack.