Inheritance and the Staggered Start

To heir is human.

—Jeffrey P. Rosenfeld, Legacy of Aging

A common metaphor for the competition to get ahead in life is the foot race. The imagery is that the fastest runner—presumably the most meritorious—will be the one to break the tape at the finish line. But in terms of economic competition, the race is rigged. If we think of money as a measure of who gets how much of what there is to get, the race to get ahead does not start anew with each generation. Instead, it is more like a relay race in which we inherit a starting point from our parents. The baton is passed, and for a while, both parents and children run together. When the exchange is complete, the children are on their own as they position themselves for the next exchange to the next generation. Although each new runner may gain or lose ground in the competition, each new runner inherits an initial starting point in the race.

In this intergenerational relay race, children born to wealthy parents start at or near the finish line, while children born into poverty start behind everyone else. Those who are born close to the finish line need no merit to get ahead. They already are ahead. The poorest of the poor, however, need to traverse the entire distance to get to the finish line on the basis of merit alone. In this sense, meritocracy applies strictly only to the poorest of the poor; everyone else has at least some advantage of inheritance over others that places them ahead at the start of the race.

In comparing the effects of inheritance and individual merit on life outcomes, the effects of inheritance come first, followed by the effects of individual merit—not the other way around. Figure 3.1 depicts the intergenerational relay race to get ahead. The solid lines represent the effects of inheritance on economic outcomes. The dotted lines represent the potential effects of merit. The “distance” each person needs to reach the finish line on the basis of merit depends on how far from the finish line each person starts the race in the first place.

It is important to point out that equivalent amounts of merit do not lead to equivalent end results. If each dash represents one “unit” of merit, a person born poor who advances one unit on the basis of individual merit over a lifetime ends up at the end of her life one unit ahead of where she started but still at or close to poverty. A person who begins life one unit short of the top can ascend to the top based on an equivalent one unit of merit. Each person is equally meritorious, but his or her end position in the race to get ahead is very different.

Heirs to large fortunes in the world start life at or near the finish line. Barring the unlikely possibility of parental disinheritance, there is virtually no realistic scenario in which they end up destitute—regardless of the extent of their innate talent or individual motivation. Their future is financially secure. They will grow up having the best of everything and having every opportunity money can buy.

Most parents want the best for their children. Except in relatively rare cases of child abuse or neglect, most parents try to do everything possible to secure their children’s futures. Indeed, the parental desire to provide advantages for children may even have biological origins. Under the “inclusive fitness-maximizing” theory of selection, for instance, beneficiaries are favored in inheritance according to their biological relatedness and reproductive value. Unsurprisingly, research shows that benefactors are much more likely to bequeath estates to surviving spouses and children than to unrelated individuals or institutions (Schwartz 1996; Willenbacher 2003). Moreover, most parents relish any opportunity to boast about their children’s accomplishments. Parents are typically highly motivated to invest in their children’s future in order to realize vicarious prestige through the successes of their children, which may, in turn, be seen as a validation of their own genetic endowments or child-rearing skills. Finally, in a form of what might be called “reverse inheritance,” parents may be motivated to invest in children to secure their own futures in the event that they become unable to take care of themselves.

Regardless of the source of parental motivation, the point is that most parents clearly wish to secure their children’s futures. The key difference among parents is not in parental motivation to pass on advantages to the next generation but in the capacity to do so, with some parents having more resources than others. For instance, at the turn of the twenty-first century in the United States, parents in the highest income quintile could spend $50,000 per child per year on food, housing, and other goods and services, but those in the bottom income quartile could only spend $9,000 per child per year (Moynihan, Smeeding, and Rainwater 2004). To the extent that parents are actually successful in passing on advantages to children, existing inequalities are reproduced across generations, and meritocracy does not operate as the basis for who ends up with what. Despite the pervasive ideology of meritocracy, the reality in America, as elsewhere, is inheritance first and merit second.

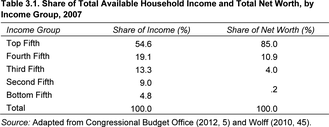

In considering how parents pass on advantages to children in the race to get ahead, researchers have usually looked at occupational mobility, that is, at how the occupations of parents affect the occupations of children. The results of this research show that parental occupation has strong effects on children’s occupational prospects. Some of this effect is mediated through education; that is, the prestige of parental occupation increases the educational attainment of children, which in turn increases the prestige of the occupations they attain. Looking at occupational prestige alone, however, underestimates the full extent of inequality in society and overestimates the amount of movement within the system. A fuller appreciation of what is at stake requires examination of the kind and extent of economic inequality within the system—who gets how much of what there is to get. Economic inequality includes inequalities of both income and wealth. Income is typically defined as the total flow of financial resources from all sources (e.g., wages and salaries, interest on savings and dividends, pensions, and government transfer payments such as Social Security, welfare payments, and other government payments) in a given period, usually annually. Wealth refers not to what people earn but to what they own. Wealth is usually measured as net worth, which includes the total value of all assets owned (such as real estate, trusts, stocks, bonds, business equity, homes, automobiles, banking deposits, insurance policies, and the like) minus the total value of all liabilities (e.g., loans, mortgages, credit card and other forms of debt). For purposes of illustration, income and wealth inequalities are usually represented by dividing the population into quintiles and showing how much of what there is to get goes to each fifth, from the richest fifth of the population down to the poorest fifth. These proportions are illustrated in table 3.1.

In terms of income, in 2009 the richest 20 percent of households received a 50.8 percent share of all before-tax income, compared to only 5.1 percent received by the bottom 20 percent. As income increases, so does its level of concentration. The top 10 percent alone accounts for 36 percent, and the top 5 percent alone accounts for 25.9 percent of the total (Congressional Budget Office 2012, 5). Moreover, income has great staying power over time. That is, the same households in the top income group now are very likely to have been in the top income group in previous years (Mishel et al. 2012, 144).

Another indication of income inequality is revealed by a comparison of pay for the chief executive officers of major corporations with that of rank-and-file employees. CEO pay as a ratio of average worker pay increased from 18.3 to 1 in 1965 to 231 to 1 in 2011 (Mishel and Sabadish 2012), with much of the compensation package for CEOs coming in the form of stock options. Since CEO compensation is increasingly in the form of stock options, the ratio to worker pay in recent years is sensitive to changes in the market but always substantially higher than in previous decades; it is also substantially higher than the ratio of CEO-to-worker pay in other advanced industrial countries (Kalleberg 2011, 110).

When wealth is considered, the disparities are much greater. In 2010, the richest 10 percent of American households accounted for 74.5 percent of total net household wealth (Levine 2012a). The bottom 50 percent combined, by stark contrast, held 1.1 percent of all available net worth. At the bottom end of the wealth scale in 2007, 18.6 percent of households had zero or negative net worth, which is the highest it has been over the past twenty-four years (Wolff 2010, 10). In other words, a significant number of Americans either own nothing or owe more than they own.

As MIT economist Lester Thurow has observed, “Even among the wealthy, wealth is very unequally distributed” (1999, 200). In 2010, for instance, the top 1 percent of all wealth holders with an average household net worth of approximately $16 million and average annual income of over $1 million accounted for 35.4 percent of all net worth, 42.1 percent of financial wealth, and 17.2 percent of annual income (Wolff 2012, 58–60). The top 1 percent of the wealthiest households (representing about three million Americans) is significant not only for the amount of wealth held that sets this group distinctly apart from the rest of American society, but for the source of that wealth. Most of the wealth held by these top wealth holders comes not from wages and salary but from investments. In 2010 the top 1 percent of households held a staggering 61.4 percent of all business equity, 64.4 percent of all financial securities, 38 percent of all trusts, 48.8 percent of all stocks and mutual funds, and 35.5 percent of all nonhome real estate (Wolff 2012, 69). Because of the amount of ownership highly concentrated in this group, the top 1 percent of wealth holders are often referred to as “the ownership class” and are used as a proxy threshold for inclusion in the American “upper class.”

In short, the degree of economic inequality in the United States is substantial by any measure. In fact, the United States now has greater income inequality and higher rates of poverty than other industrial countries (Wilkinson and Pickett 2009; Grusky and Krichell-Katz 2012; Mishel et al. 2012; Kerbo 2006; Smeeding, Ericson, and Jantti 2011; Salverda, Nolan, and Smeeding 2009; Sieber 2005). Moreover, the extent of this inequality is increasing. One standard measurement of the extent of inequality is the Gini coefficient, which measures the extent of the discrepancy between the actual distribution of income and a hypothetical situation in which each quintile of the population receives the same percentage of income. Values of the Gini coefficient range between zero and one, where zero indicates complete equality and one indicates complete inequality. Thus, the higher the number, the greater the degree of inequality. Using reports from the U.S. Census Bureau, Levine (2012b) demonstrates that the Gini coefficient for the United States has steadily and incrementally increased from 0.386 in 1968 to 0.469 in 2010—representing a 21.5 percent increase over a forty-two-year span.

Increases in wealth inequality are even more dramatic. The ratio of wealth of the top 1 percent of wealth holders to median wealth had increased from 125 times the median in 1962 to 225 times by 2009 (Mishel et al. 2012, 383). In short, the gap between those who live off investments and the large majority of people who work for a living has widened considerably in recent decades.

It is instructive to point out that this level of wealth inequality is greatly underestimated by the American public. A recent Duke University study showed that Americans estimate that the richest 20 percent of Americans account for 59 percent of the total wealth available, compared to the actual 84 percent (Norton and Ariely 2011). Moreover, in the same survey, Americans indicated that ideally the richest 20 percent should own 32 percent of the total wealth or about 50 percent less than they actually hold.

Consideration of wealth as opposed to just income in assessing the total amount of economic inequality in society is critical for several reasons. First, the really big money in America comes not from wages and salaries but from owning property, particularly the kind that produces more wealth. If it “takes money to make money,” those with capital to invest have a distinct advantage over those whose only source of income is wages. Apart from equity in owner-occupied housing, assets that most Americans hold are the kind that tend to depreciate in value over time: cars, furniture, appliances, clothes, and other personal belongings. Many of these items end up in used-car lots, garage sales, and flea markets selling at prices much lower than their original cost. The rich, however, have a high proportion of their holdings in the kinds of wealth that appreciate in value over time. Second, wealth is especially critical with respect to inheritance. When people inherit an estate, they inherit accumulated assets—not incomes from wages and salaries. Inheritance of estates, in turn, is an important nonmerit mechanism for the transmission of privilege across generations. In strictly merit terms, inheritance is a form of getting something for nothing.

Defenders of meritocracy sometimes argue that the extent of economic inequality is not a problem as long as there is ample opportunity for social mobility based on individual merit. Overwhelming evidence, however, shows that a substantial amount of economic advantage is passed on across generations from parents to children (Ermisch, Jantti, and Smeeding 2012; Smeeding, Erikson, and Jantti 2011). The mechanisms by which parental privilege are transferred to children are varied, including direct advantages such as inheritance of material resources to indirect advantages such as increased capacity and opportunity for cognitive and physical development, better educational preparedness and opportunities, access to influential social networks, and access and exposure to prestigious cultural resources.

One way to measure the extent of intergenerational mobility is the correlation between parent and child incomes. Correlations can range from a low of zero to a high of one. If we had a pure merit system and assumed random transfer of genetic endowments across generations, we would expect a correlation of parent and adult child incomes to approach zero. On the other hand, in a strict caste system in which children inherit entirely the social position of parents and in which no mobility occurs, we would expect a correlation to approach one. The correlation between parents’ and adult children’s incomes in the United States is actually about 0.50 (Stiglitz 2012), a correlation midway between these extremes. This figure is much larger than in other industrial nations (Pew Economic Mobility Project 2011).

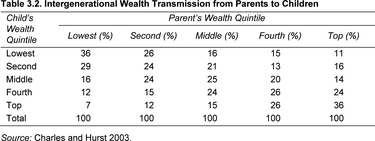

Table 3.2 shows the extent of intergenerational wealth transfers from parents to children as calculated by economists Kerwin Charles and Erik Hurst (2003). This study compares wealth of children and parents in wealth quintiles. These data show a great deal of “stickiness” between generations, especially in the top and bottom quintiles. For instance, 36 percent of children born to parents in the lowest quintile remain in the lowest quintile as adults, while, correspondingly, 36 percent of those born to parents in the top wealth quintile remain there as adults. Most movement that does take place between generations occurs as “short-distance” mobility between adjacent quintiles, especially in the middle quintile ranges. In short, most people stay at, or very close to, where they started, with most of the movement occurring as short-distance mobility in the middle ranges.

Another source of information on wealth transfers is the annual list of the four hundred wealthiest Americans published by Forbes magazine. A recent study of the 2011 Forbes list (United for a Fair Economy 2012) indicates that roughly 40 percent of those listed had inherited a sizable asset from a spouse or family member, defined as at least a medium-size business or wealth in excess of $1 million. Roughly 20 percent of those on the list inherited sufficient wealth of at least the $1 billion minimum required to make it on the list through inheritance alone. Among the eleven wealthiest Americans on the 2011 Forbes list, six (ranked nos. 6, 9, 10, 11, 103, and 139) are heirs of Sam Walton, founder of the Walmart empire. The six Walton heirs have a combined estimated net worth of $93 billion, which is equal to the wealth of the bottom 41.5 percent of all American families. An earlier study of the 1982 Forbes list (Canterbery and Nosari 1985) also showed that at least 40 percent of that year’s list inherited at least a portion of their wealth, and the higher on the list, the greater the likelihood that wealth was derived from inheritance.

Although there is some movement over time onto and off the Forbes list of the richest four hundred Americans, this does not mean that those who fall off the list have lost or squandered their wealth. Most likely, when wealthy individuals fall off the Forbes list, they have not lost wealth at all but rather have not gained it as quickly as others. Although those who fall off the four hundred list may have lost ground relative to others, they typically still have vast amounts of wealth and most likely remain well within the upper 0.01 percent of the richest Americans.

Research has shown that there is a remarkable level of stability among the listings in the Forbes 400. In one recent study of the Forbes list, over a sixteen-year period between 1995 and 2003, the percentage of those who remained on the list from one year to the next (excluding those who fell off the list because of death) ranged from a low of 84 percent in the 1998–1999 period to a high of 95 percent in the 2002–2003 period (Sauls 2012). Moreover, how individuals ranked within the list is also very stable from year to year. Over the same sixteen-year period, the correlation of rankings from one year to the next varied from a low of .82 in 2000–2001 to a high of .93 in 2009–2010, with an average of .89 for all years combined.

The increasing degree of concentration of wealth and the high stability of wealth over time is particularly significant given the large amount of wealth available for transfer across generations. A recent study estimates that baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 are likely to inherit a total of $8.4 trillion in bulk estates (MetLife Mature Market Institute 2010). An earlier study estimated that over a fifty-five-year period from 1998 through 2052, a total of $41 trillion will be available for transfer ($25 trillion to heirs, $8 trillion to taxes, $6 trillion to charity, and $2 trillion to estate fees) (Havens and Schervish 2003). These vast amounts of wealth will not simply evaporate between generations, and indeed much of the intergenerational transfer will reach not only to the current generation of baby boomers but to their children as well, further solidifying the continuity of wealth inequality overtime. Indeed, the combination of increasing amounts and concentration of wealth at the top of the system and the stability of wealth and inequality across generations gives rise to what some observers suggest is the unfolding of a second Gilded Age of dynastic wealth in America (Grusky and Kricheli-Katz 2012; Freeland 2012).

Despite the evidence of wealth stability over time, much is made of the investment “risks” that capitalists must endure to justify returns on such investments. And to some extent, this is true. Most investments involve some measure of risk. The superwealthy, however, protect themselves as much as possible from the vicissitudes of “market forces”—most have professionally managed, diversified investment portfolios. As a result, established wealth has great staying power. In short, what is good for America is, in general, good for the ownership class. The risk endured, therefore, is minimal. Instead of losing vast fortunes overnight, the more common scenario for the superrich is for the amount of their wealth to fluctuate with the ups and downs in the stock market as a whole. And, given the very high levels of aggregate and corporate wealth concentration in the economy, the only realistic scenario in which the ownership class goes under is one in which America as a whole goes under.

Inheritance is more than bulk estates bequeathed to descendants; more broadly defined, it refers to the total impact of initial social-class placement at birth on future life outcomes. Therefore, it is not just the superwealthy who are in a position to pass advantages on to children. Advantages are passed on, in varying degrees, to all of those from relatively privileged backgrounds. Even minor initial advantages may accumulate during the life course. In this way, existing inequalities are reinforced and extended across generations. As Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith put it in the opening sentence of his well-known book The Affluent Society, “Wealth is not without its advantages and the case to the contrary, although it has often been made, has never proved widely persuasive” (1958, 13). Specifically, the cumulative advantages of wealth inheritance include those discussed below.

Children of the privileged enjoy a high standard of living and quality of life regardless of their individual merit or lack of it. For the privileged, this not only includes high-quality food, clothing, and shelter but also extends to luxuries such as travel, vacations, summer camps, private lessons, and a host of other enrichments and indulgences that wealthy parents and even middle-class parents bestow on their children (Duncan and Murnane 2011; Lareau 2011; Smeeding, Erikson, and Jantti 2011). These advantages do not just reflect a higher standard during childhood but have important long-term consequences for future life chances. Children raised in privileged settings are much more likely to have better and more rapid physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development, better school readiness, and higher academic achievement. Conversely, children raised in poverty have higher risks for basically everything that is bad that can happen to them as adults later in life—dropping out of school, becoming victims of crime and violence, having more physical and mental health problems, having lower economic prospects, and having greater likelihood of familial disruption. The more severe these deprivations and the earlier they occur, the greater the negative consequences (Duncan and Murnane 2011; Smeeding, Erikson, and Jantti 2011). In short, the effects of early childhood development have a “long reach” into later life. It is important to emphasize that children of privilege do not “earn” a privileged childhood lifestyle; they inherit it and benefit from it long before their parents are deceased.

Cultural capital refers to what one needs to know to function as a member of the various groups to which one belongs. (We address the issue of cultural capital more fully in chapter 4.) All groups have norms, values, beliefs, ways of life, and codes of conduct that identify the group and define its boundaries. The culture of the group separates insiders from outsiders. Knowing and abiding by these cultural codes of conduct are required to maintain one’s status as a member in good standing within the group. By growing up in privilege, children of the elite are socialized into elite ways of life. This kind of cultural capital has commonly been referred to as “breeding,” “refinement,” “social grace,” “savoir faire,” or simply “class” (meaning upper class). Although less pronounced and rigid than in the past, these distinctions persist into the present. In addition to cultivated tastes in art and music (“highbrow” culture), cultural capital includes, but is not limited to, interpersonal styles and demeanor, manners and etiquette, and vocabulary. Those from more humble backgrounds who aspire to become elites must acquire the cultural cachet to be accepted in elite circles, and this is no easy task. Those born to it, however, have the advantage of acquiring it “naturally” through inheritance, a kind of social osmosis that takes place through childhood socialization (Lareau 2011).

Everybody knows somebody else. Social capital refers to the “value” of whom you know. (We review the importance of social capital on life outcomes more fully in chapter 4.) For the most part, privileged people know other privileged people, and poor people know other poor people. Another nonmerit advantage inherited by children of the wealthy is a network of connections to people of power and influence. These are not connections that children of the rich shrewdly foster or cultivate on their own. The children of the wealthy travel in high-powered social circles; these connections provide access to power, information, and other resources. The difference between rich and poor is not in knowing people; it is in knowing people in positions of power and influence who can do things for you.

Children of the privileged do not have to wait until their parents die to inherit assets from them. Inter vivos transfers of funds and “gifts” from parents to children can be substantial, and in many cases represent a greater proportion of intergenerational transfers than lump-sum estates at death. Parents provide inter vivos transfers to children to advance their children’s current and future economic interests, especially at critical junctures or milestones of the life cycle (Oliver and Shapiro 2006; Zissimopoulos and Smith 2011). These transfers continue beyond early childhood and include milestone events for adult children such as going to college, getting married, buying a house, and having their own children, or at crisis events such as income shocks related to job loss, divorce, or medical crisis. At each event, there may be a substantial infusion of parental capital—in essence an early withdrawal on the parental estate. The amounts transferred are highly skewed. One recent study of parents over the age of fifty (Zissimopoulos and Smith 2011), for instance, showed that in the United States over a sixteen-year period, the bottom 50 percent of parental households gave an average of only $500 to their adult children, but parents in the top 1 percent gave an average of $137,641 per child to their adult children. Moreover, households that give substantially to children give more as a percentage of their total income and wealth than other households, further reflecting the differential capacity of parents to transfer advantages across generations. For those with great wealth, inter vivos gifts to children also provide a means of legally avoiding or reducing estate taxes. In this way, parents can “spend down” their estates during their lives to avoid estate and inheritance taxes upon their deaths.

One of the most common current forms of inter vivos gifts is payment for children’s education. (We address education more fully in chapter 5.) A few generations ago, children may have inherited the family farm or the family business. With the rise of the modern corporation and the decline of family farms and businesses, inheritance increasingly takes on more fungible or liquid forms, including cash transfers. Indeed, for many middle-class Americans, education has replaced tangible assets as the primary form by which advantage is passed on between generations. Also, with rising overall life expectancy, there is a longer period of time during the lives of parents and children in which inter vivos gifts can take place.

If America were truly a meritocracy, we would expect fairly equal amounts of both upward and downward mobility. Until very recently and for most of American history, however, there have been much higher rates of upward than downward mobility. There are two key reasons for this. First, most mobility that people have experienced in America in the past century, particularly occupational mobility, was due to industrial expansion and the rise of the general standard of living in society as a whole. Sociologists refer to this type of mobility as “structural mobility,” which has more to do with changes in the organization of society than with the merit of discrete individuals. (We discuss the effects of social structure on life outcomes in more detail in chapter 6.) A second reason why upward mobility is more prevalent than downward mobility is that parents and extended family networks insulate children from downward mobility. That is, parents frequently “bail out,” or “rescue,” their adult children in the event of life crises such as sickness, unemployment, divorce, or other setbacks that might otherwise propel adult children into a downward spiral. In addition to these external circumstances, parents also rescue children from their own failures and weaknesses, including self-destructive behaviors. Parental rescue as a form of inter vivos transfer is not a generally acknowledged or well-studied benefit of inheritance. Indirect evidence of parental rescue may be found in the recent increase in the number of “boomerang” children, adult children who leave home only to return later to live with their parents. Kim Parker of the Pew Research Center (2012) reports that 39 percent of all young adults, ages eighteen to thirty-four, either were currently living with their parents or had moved back in temporarily in the past. The reasons for adult children returning to live at home are usually financial: adult children may be between jobs, between marriages, or without other viable means of self-support.

If America operated as a “true” merit system, people would advance solely on the basis of merit and fail when they lacked merit. In many cases, however, family resources prevent, or at least reduce, “skidding” among adult children. One of the authors of this book recalls that when he left home as an adult, his parents took him aside and told him that no matter how bad things became for him out there in the world, they would send him money to come home. This was his insurance against destitution. Fortunately, he did not take his parents up on their offer, but neither has he forgotten it. Without always being articulated, the point is that this informal familial insurance against downward mobility is available, in varying degrees, to all except the poorest of the poor, who simply have no resources to provide.

From womb to tomb, the more affluent one is, the less the risk of injury, illness, and death (Budrys 2010; Cockerham 2012; National Center for Health Statistics 2011; Weitz 2013). Among the many nonmerit advantages inherited by those from privileged backgrounds is higher life expectancy at birth and a greater chance of better health throughout life. For instance, research has found that individuals in the top decile of income have a life expectancy that is about seven years longer than individuals in the bottom decile (Peltzman 2009). There are several reasons for the strong and persistent relationship between socioeconomic status and health. Beginning with fetal development and extending through childhood, increasing evidence points to the impact of early childhood on adult health. Prenatal deprivations, more common among the poor, for instance, are associated with later life conditions such as retardation, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and hypertension. Poverty in early childhood is also associated with increased risk of adult diseases. This may be due in part to higher stress levels among the poor and less control over that stress. Cumulative wear and tear on the body over time occurs under conditions of repeated high stress. Another reason for the health-wealth connection is that the rich have greater access to quality health care. Even with the recent passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act in 2010 (more commonly referred to as Obamacare), access to quality health care in America is still largely for sale to the highest bidder. Under these conditions, prevention and intervention are more widely available to the more affluent. Finally, not only does lack of income lead to poor health, but poor health leads to reduced earnings. That is, if someone is sick or injured, he or she may not be able to work or may have limited earning power.

Overall, the less affluent are at a health disadvantage due to higher exposure to a variety of unhealthy living conditions. The less affluent, for instance, are also likely to have nutritional deprivations and, ironically, are also more likely to be obese. Obesity is related to poor nutrition linked to diets that are high in low-cost sugar and carbohydrates and low in high-cost fruits, vegetables, and other sources of protein. The less affluent are also more likely to be exposed to physical risks associated with crowding, poor sanitation, and living in closer proximity to chemical and biological sources of pollution (Brulle and Pellow 2006).

Part of the exposure to health hazards is occupational. According to the U.S. Department of Labor (2012), those in the following occupations (listed in order of decreasing risk) have the greatest likelihood of being killed on the job: fishers, timber cutters, airplane pilots, sanitation workers, roofers, structural metal workers, farmers and ranchers, truck and delivery drivers, electrical power-line workers, and taxicab drivers. With the exception of airline pilot, all the jobs listed are working-class jobs. Since a person’s occupation is strongly affected by family background, the prospects for generally higher occupational health risks are in this sense at least indirectly inherited. Finally, although homicides constitute only a small proportion of all causes of death, it is worth noting that the less affluent are at higher risk for being victims of violent crime, including homicide.

Some additional risk factors are related to individual behaviors, especially smoking, drinking, and drug abuse—all of which are more common among the less affluent (Budrys 2010). Evidence suggests that these behaviors, while contributing to poorer health among the less affluent, are responsible for only about one-third of the “wealth-health gradient” (Smith 1999, 157). These behaviors are also associated with higher psychological as well as physical stress. Indeed, the less affluent are not just at greater risk for physical ailments; research has shown that the less affluent experience higher levels of stress and are at significantly higher risk for mental illness as well (Cockerham 2011; Weitz 2013). Despite the adage that “money can’t buy happiness,” social science research has consistently shown that happiness and subjective well-being tend to be related to the amount of income and wealth people possess (Frey and Stutzer 2002; Layard 2005; Schnittker 2008; Wilkinson and Pickett 2009). This research shows that people living in wealthier (and more democratic) countries tend to be happier and that rates of happiness are sensitive to overall rates of unemployment and inflation. In general, poor people are less happy than others, although increments that exceed average amounts of income are negligibly related to levels of happiness. That is, beyond relatively low thresholds, additional increments of income and wealth are not likely to result in additional increments of happiness. Although money may not guarantee a long, happy, and healthy life, a fair assessment is that it aids and abets it.

Whatever assets one has accumulated in life that remain at death represent a bulk estate. “Inheritance” is usually thought to refer to bequests of such estates. Because wealth itself is highly skewed, so are bequests from estates. Beyond personal belongings and items of perhaps sentimental value, most Americans at death have little or nothing to bequeath. There is no central accounting of small estates, so reliable estimates on the total number and size of estates bequeathed are difficult to come by. Prior to the current baby boom generation, only about 20 percent of all households reported having received a bequest (Joulfaian and Wilhelm 1994; Ng-Baumhackl, Gist, and Figueiredo 2003). As a likely result of the combination of post–World War II growth and prosperity and the frugality of the “Greatest Generation” who came of age during this period, new estimates suggest that as many as two-thirds of baby boomers will eventually receive some inheritance (MetLife Mature Market Institute 2010). However, as wealth is highly skewed, so too are estates. Among the two-thirds of baby boomers who expect to receive at least some inheritance, households in the top wealth decile anticipate an average inheritance of $1.1 million compared to an average of $9,000 for households in the bottom wealth decile (MetLife Mature Market Institute 2010). And, as we have seen, even among the top wealth decile, wealth is highly skewed so that “average” is likely highly skewed to a relatively small portion of very wealthy family fortunes receiving much larger sums. In short, although few are likely to inherit great sums, bequests from estates are nevertheless a major mechanism for the transfer of wealth and privilege across generations (McNamee and Miller 1989, 1998; Miller, Rosenfeld, and McNamee 2003).

Some may argue that those who receive inheritances often deplete them in short order through spending sprees or unwise investments and that the playing field levels naturally through merit or lack of it. Although this may occur in isolated cases, it is not the general pattern—at least among the superwealthy. Although taking risks may be an appropriate strategy for acquiring wealth, it is not a common one for maintaining wealth. Once secured, the common strategy for protecting wealth is to play it safe—to diversify holdings and make safe investments. The superwealthy often have teams of accountants, brokers, financial planners, and lawyers to “manage” portfolios for precisely this purpose. One of the common ways to prevent the quick spending down of inheritances is for benefactors to set up “bleeding trusts” or “spendthrift trusts,” which provide interest income to beneficiaries without digging into the principal fund. Despite such efforts to protect wealth, estates may, in some families, be gradually diminished over generations through subdivision among descendants. The rate at which this occurs, however, is likely to be slow, especially given the combination among the wealthy of low birthrates and high rates of marriage within the same class. Even in the event of reckless spending, poor financial management, or subdivision among multiple heirs, the fact remains that those who inherit wealth benefit from it and benefit from opportunities that such wealth provides, for as long as it lasts, regardless of how personally meritorious they may or may not be.

In his 1926 short story “The Rich Boy,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” By the very rich, we mean the 1 percent or so of Americans who own nearly 40 percent of all the net worth in America. Most of the very rich either inherited their wealth outright or converted modest wealth and privilege into larger fortunes. How different are they? By the sheer volume and type of capital owned, this group is set apart from other Americans. This group is further distinguished by common lifestyles, shared relationships, and a privileged position in society that produce a consciousness of kind (Domhoff 2009). In short, they are a class set apart in both economic and social terms. Using surveys and simulations, sociologist Lisa Keister (2000) created a demographic profile of the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans. Compared to all households, the wealthiest 1 percent are much more likely to be white (96 percent for the top 1 percent compared to 82 percent for the general population), between forty-five and seventy-four years of age (73 percent for the top 1 percent compared to 41 percent for all households), and college educated (68 percent for the top 1 percent compared to 22 percent for all households). As one might expect, the upper class is about equally divided between men and women, but men have historically played a more dominant role within the upper class (Chang 2010). Besides being almost exclusively white, the inner circle of the upper class has historically been predominantly Protestant and of Anglo-Saxon heritage. The acronym WASP (for white Anglo-Saxon Protestant) was first coined by sociologist E. Digby Baltzell, himself a member of the upper class, to describe its social composition. Although the upper class is gradually becoming less exclusively WASP (Zweigenhaft and Domhoff 2006), there is still a strong association of upper-class status with WASP background. Beyond these demographic characteristics, how else are the rich different from most other Americans?

An important defining characteristic of the upper class is that it is exclusive. Wealth in America is highly concentrated. Money alone, however, does not grant full admission into the highest of elite circles. Full acceptance requires the cultural capital and cachet that only “old money” brings. And “old money” means inherited money. The exclusiveness of old money is exemplified by the Social Register, a list of prominent upper-class families first compiled in 1887. The list has been used by members of the upper class both to recognize distinction and as a guide for issuing invitations to upper-class social events. For years separate volumes of the Social Register were published in different cities throughout the United States. But since the Malcolm Forbes family took over the publication in 1976, the Social Register has been consolidated into one national book. To be listed, a potential member must have five letters of nomination submitted by those already on the list and not be “blackballed” by any current members. There is great continuity across generations among the names included in these volumes. One study (Broad 1996), for instance, shows that of the eighty-seven prominent founders of family fortunes listed in the 1940 Social Register, 92 percent had descendants listed in the 1977 volume. The percentage of descendants of these prominent families included in the 1995 volume, fifty-five years later, dipped only slightly to 87 percent. Highlighting connections to the past, almost half of those listed in 1995 attached Roman numerals to their surnames, such as II, III, IV, V, VI, and so on. Another common practice among upper-class families is to use maternal surnames as first names or middle names. The use of these “recombinant” names highlights connections to prominent families on both sides as well as patterns of intraclass marriage. Almost 50 percent of those listed in 1995 had such recombinant names. Most social clubs of the upper class also show connections to the past—if only because they have been in existence for a long time and their membership shows intergenerational continuity (Kendall 2008; Sherwood 2010).

It is not mere coincidence that the upper class has great reverence for the past. In a highly meritocratic culture, it is an ongoing challenge for those who inherit great wealth to justify their claim to it. The past, therefore, is a source of the justification of wealth for the upper class and a claim to status.

The children of the wealthy in America are not immune to the ideology of meritocracy that pervades the culture as a whole. Justification of the inheritance of wealth is a prevalent theme among those who were born into wealth (Aldrich 1988; Forbes 2010; Schervish, Coutsoukis, and Lewis 1994). As one inheritor of an oil fortune put it, “The feelings of guilt put me through much agony. For a long, long, long time, it gave me low self-esteem: who am I to deserve all of this good fortune?” (Schervish, Coutsoukis, and Lewis 1994, 118). Unlike the children of European aristocrats who felt entitled to privilege as a matter of birthright, American children of great wealth are victims of an ideology that, through no fault of their own, essentially invalidates them.

In addition to exclusivity, the upper class in America is relatively anonymous and hidden from the public view. A second defining characteristic of the upper class in America is that it is isolated. The upper class is separated from the mainstream of society in a world of privacy: remote private residences, private schools, private clubs, private parties, and private resorts. With the exception of service staff, throughout their lives, upper-class individuals interact mostly with people like themselves. The geography of the upper class shows a distinct pattern of isolation, intentionally maintained and reinforced through land-use strategies that include incorporation, zoning, and restrictive land covenants (Higley 1995). Houses and mansions are tucked away in exclusive communities. Individual residences within these communities, often with long and meandering driveways, are typically set back from the public roads that connect them with the larger world. Once approached, the residences are fortresses of security, complete with bridges, fences, gates, guard dogs, and sophisticated electronic surveillance. Children raised within these confines are isolated as well, separated from the outside world by a series of private nannies, private tutors, private preparatory boarding schools, and private elite Ivy League colleges. Even travel within the upper class is often isolated—in private planes and limos and on private yachts. And even when resorting to more commercial forms of transportation, there is always the more isolated and pampered option of traveling “first class.”

The upper-class tendency to isolate itself geographically from the rest of society has been emulated by the upper middle classes. The overall trend is toward greater socioeconomic residential segregation in American society as a whole (Massey, Rothwell, and Domina 2009). The creation of white-flight suburbs in the post–World War II era began a trend that has now extended to the rising popularity of “gated” communities (Blakely and Snyder 1997). Once restricted to the superwealthy and some retirement villages, gated communities are now for the merely privileged.

One reason for this self-imposed isolation is security. Those who have more have more to lose. Keeping potential criminals out, however, also has the effect of keeping the rich in. In addition to concerns about property theft or vandalism, the superwealthy are also concerned about the potential for kidnapping, which is a real concern for those of great wealth who might be targeted for ransom.

One aspect of this self-segregation is the strong tendency toward upper-class endogamy, or marriage within one’s own social class (Cherlin 2009; Elmelech 2008, 55–57; Van Leeuwen, Mass, and Miles 2006; Carlson and England 2011). Despite the romantic ideal that “love is blind” and that love is mostly a random process in which anyone can fall in love at any place at any time (as portrayed in countless songs, novels, and movies), the social reality is that mate selection is a very structured process in which people tend to marry people who replicate their own social profile at rates far in excess of random chance alone. That is, people tend to marry people of similar age, education, race, religion, and social-class background. There are three primary possible reasons for this nonrandom convergence (Kalmijn 1998): (1) everything else being equal, people may prefer to marry people like themselves; (2) third parties (e.g., friends, family, and sometimes institutions such as religious groups or the state) may encourage or even require such convergence; and (3) apart from intentional personal preference or outside pressure, people may tend to marry people from within their own social milieu or social circles of acquaintances, which in turn would substantially increase the probability of marrying someone like themselves. Although in the modern era, third-party influence has been greatly reduced (although not eliminated), continued or even increased patterns of social segregation increase the probability of marital demographic convergence (homogamy) far beyond random chance alone. Kalmijn and Flap (2001) have identified five potential “meeting settings” that highly structure the prospects of marriage: work, school, residence, common family networks, and voluntary associations (such as religious, political, and other cultural organizations that individuals voluntarily belong to). In a preliminary study conducted in the Netherlands, Kalmijn and Flap (2001) found, for instance, that 42 percent of married couples had met in one of these five institutional settings. Of these settings, the one in which couples were most likely to have initially met was educational settings. Moreover, the higher the level of education achieved, the more likely couples would have met in those settings.

These findings are consistent with other research conducted in the United States that show high rates of educational endogamy, especially at very high and very low levels of educational attainment (Rosenfeld 2008; Schwartz and Mare 2005). To the extent that educational endogamy occurs and to the extent that access to education is class based (see chapter 5), the likelihood of class endogamy also increases. Class endogamy through education can occur in two ways. One way is that those of the same social-class background (class of origin) are more likely to go to the same kinds of schools and have the same levels of educational attainment. A second way is that those who are from lower social-class origins who are upwardly mobile are more likely to end up in educational and work settings that increase the prospect of marrying someone from a higher social class of origin compared to those who are not upwardly mobile. Historically, the prospect for upward mobility through marriage has been greater for women than men. In what might be referred to as the “Cinderella effect,” early research seemed to show that women could sometimes trade attractiveness in a marriage market for access to higher-status men (Elder 1969). This presumed tradeoff, however, risks social derision, for instance, in situations in which substantially younger “trophy” wives marry especially high-profile wealthy or successful older men. Americans do not approve of “marrying for money” as a means of upward social mobility—although if one happens to fall in love with a rich person, so much the better. How extensive an intentional marrying-for-money strategy of upward mobility exists or how successful it might be are unknown, but such strategies would not in any event meet with social approval and would not generally be considered a legitimate part of the American Dream.

With greater gender equality and greater female participation in the labor force, it is likely that this avenue for upward mobility for females has declined. Evidence suggests, for instance, that as women’s labor force participation has increased, men are likely to be competing for high-earning, highly educated women as women have traditionally competed for high-earning men (Schwartz and Mare 2005).

Given the high level of social isolation of the upper class, upper-class endogamy is likely to be especially high. Traditional upper-class social institutions such as the debutante ball, at which young upper-class women are first “presented” to “society,” certainly increase these probabilities. As sociologist Digby Baltzell put it, “The debutante ritual is a rite de passage which functions to introduce the post-adolescent into the upper-class adult world, and to insure upper-class endogamy as a normative pattern of behavior, in order to keep important functional class positions within the upper class” (1992, 60). Other upper-class institutions include elite boarding prep schools, elite social clubs, and elite summer resorts, all of which provide settings and organized activities that bring upper-class young adults together. Combining upper-class and upper-middle-class familial assets through marriage and then transferring those assets to children born into these families further solidifies nonmerit economic advantage across generations.

Poor and working-class families on the other hand are much less likely to be married in the first place, much more likely to have children outside of marriage, and more likely to experience familial disruption through divorce—all of which have adverse economic consequences (Carlson and England 2011). Moreover all of these trends have accelerated in the past several decades. Some have argued that the increase in familial instability especially among the poor and working class is related to moral breakdown, which then is seen as itself a cause of economic instability (Murray 2012). Others (Cherlin 2009; Wilson 1987), however, point to the opposite direction of influence, that is, how economic instability creates familial instability. Research, for instance, indicates that even among poor and working-class populations in which marriage rates are low and out-of-wedlock births are high, marriage is still highly valued and preferred (Edin and Kefalas 2005; Cherlin, Cross-Barnet, Burton, and Garrett-Peters 2008). However, the recent reduction of manufacturing and construction jobs (see chapter 6) has increased economic instability among the poor and working class and has resulted in a shortage of what sociologist William Julius Wilson calls “marriageable men” with secure enough economic prospects who are not otherwise unemployed, underemployed, or incarcerated. These trends not only reduce the prospects for initial marriage but also contribute to circumstances in which existing marriages are less likely to survive.

In the late nineteenth century, America entered the Gilded Age, so named for its opulent and even ostentatious displays of great wealth. During the Gilded Age the rich competed with one another to flaunt their wealth. During this time, some of the great mansions were built, including George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, a 175,000-square-foot, 250-room, Renaissance-style chateau completed in 1895 and still the largest private house ever built in America (Frank 1999, 14). In some ways, America’s wealthy of this period were insecure about their status and were envious of the more established European aristocracy. As a result, the newfound industrial wealth in the United States patterned itself after everything old and European. With the Great Depression, such displays were no longer considered in good taste. In subsequent decades, more subdued forms of luxury were preferred. Nevertheless, a lifestyle organized around formal parties, exclusive resorts and clubs, and such upper-class leisure activities as golf, tennis, horseback riding, and yachting persisted. Some segments of the upper class indulge themselves in support of the arts—theater, opera, orchestra, and other highbrow forms of cultural consumption. Some observers of upper-class life have noted a surge in luxury spending on cars, boats, and homes as well as for such items as premium wines, fancy home appliances, and even cosmetic surgery (Frank 1999, 14–32; 2007; Brooks 2000; Taylor 1989). It should be noted, however, that the rich are not all alike in their consumption behavior. One of the advantages of being rich is that you can choose to display wealth ostentatiously or crassly or not at all. Sam Walton, for example, founder of the Walmart empire, was known to ride around in his hometown of Bentonville, Arkansas, in a beat-up Ford pickup. For the most part, however, the consumption patterns of the wealthy set them apart as a distinct social class.

In a substantial sense, the upper class in America is also a ruling class. Despite the ideology of democracy in which everyone has an equal say in deciding what happens, the reality is that those who have the most economic resources wield the most power. In Gospels of Wealth: How the Rich Portray Their Lives, sociologists Paul Schervish, Platon Coutsoukis, and Ethan Lewis describe the power of the wealthy to make things happen (and other things not happen) as “hyperagency.”

To the extent that it is possible to convert wealth into political power, the upper class can exert influence on political outcomes far beyond their numbers alone. The specific mechanisms by which this influence is exerted have been well documented (Domhoff 2009; Gilens 2012; Hacker and Pierson 2010; Phillips 2003). Beyond direct forms of influence such as substantial campaign contributions and holding government positions, economic elites exert indirect, but no less important, forms of influence through the corporate community, a policy planning network comprising foundations, think tanks and lobbies, and the media—all of which are dominated by propertied interests. For all of the key measures of political power as identified by Domhoff (2009)—who decides policy, who wins in disputes, and who benefits from political outcomes—the interests of the wealthy usually prevail.

It should be pointed out, however, that the upper class is not a political monolith. That is, as with all groups, there are always internal differences of opinion. On the estate tax issue, for instance, several very prominent members of the upper class—including Bill Gates and Warren Buffett—have been outspoken critics of proposals to abolish estate taxes. Both maintain that it is entirely appropriate for the government to heavily tax recipients of large estates as a form of unearned income, and both plan to give the bulk of their accumulated fortunes to charitable causes rather than bequeath them to heirs. Similarly, there are other members of the upper class who advocate for more equitable distribution of societal resources, including a recently formed group known as Patriotic Millionaires for Fiscal Strength consisting of 250 millionaires who in 2010 petitioned Congress and President Obama to establish a more genuinely progressive tax system (Collins 2012, 82).

The power of the upper class, while considerable, falls short of complete control. Labor unions and numerous interest groups, including civil rights groups, consumer groups, and others, chip away at the edges of the system of privilege on behalf of their constituencies. But in the final analysis, although these groups and the general public as a whole win some of the battles, propertied interests continue to win the class wars. As financier Warren Buffett noted in response to those who question the fairness of the system as “class warfare,” “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning” (New York Times 2006).

The United States has high levels of both income inequality and wealth inequality. In terms of the distribution of income and wealth, America is clearly not a middle-class society. Income and especially wealth are not evenly distributed, with a relatively small number of well-off families at one end and a small number of poor families much worse off at the other. Instead, the overall picture is one in which the bulk of the available wealth is concentrated in a narrow range at the very top of the system. In short, the distribution of economic resources in society is not symmetrical and certainly not bell shaped: the poor who have the least greatly outnumber the rich who have the most. Moreover, in recent decades, by all measures, the rich are getting richer, and the gap between the very rich and everyone else has appreciably increased.

The greater the amount of economic inequality in society, the more difficult it is to move up within the system on the basis of individual merit alone. Indeed, the most important factor in terms of where people will end up in the economic pecking order of society is where they started in the first place. Economic inequality has tremendous inertial force across generations. Instead of a race to get ahead that begins anew with each generation, the race is in reality a relay race in which children inherit different starting points from parents. Inheritance, broadly defined as one’s initial starting point in life based on parental position, includes a set of cumulative nonmerit advantages for all except the poorest of the poor. These include enhanced childhood standards of living, differential access to cultural capital, differential access to social networks of power and influence, infusion of parental capital while parents are still alive, greater health and life expectancy, and the inheritance of bulk estates when parents die.

At the top of the system are members of America’s ownership class—roughly the 1 percent of the American population who own about one-third of all the available net worth. The upper class is set apart from other Americans not only by the amount and source of the wealth it holds but by an exclusive, distinctive, and self-perpetuating way of life that reduces opportunities for merit-based mobility into it.

Aldrich, Nelson W., Jr. 1988. Old Money: The Mythology of America’s Upper Class. New York: Knopf.

Baltzell, E. Digby. 1992. The Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Blakely, Edward J., and Mary Gail Snyder. 1997. Fortress America: Gated Communities in the United States. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press.

Broad, David. 1996. “The Social Register: Directory of America’s Upper Class.” Sociological Spectrum 16:173–81.

Brooks, David. 2000. Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Brulle, Robert J., and David N. Pellow. 2006. “Environmental Justice: Human Health and Environmental Inequalities.” Annual Review of Public Health 27:102–24.

Budrys, Grace. 2010. Unequal Health: How Inequality Contributes to Health or Illness. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Canterbery, E. Ray, and Joe Nosari. 1985. “The Forbes Four Hundred: The Determinants of Super-Wealth.” Southern Economic Journal 51:1073–83.

Carlson, Marcia J., and Paula England, eds. 2011. Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Chang, Mariko Lin. 2010. Shortchanged: Why Women Have Less Wealth and What Can Be Done about It. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cherlin, Andrew J. 2009. The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today. New York: Vintage.

Cherlin, Andrew, Caitlin Cross-Barnet, Linda M. Burton, and Raymond Garrett-Peters. 2008. “Promises They Can Keep: Low-Income Women’s Attitudes toward Motherhood, Marriage, and Divorce.” Journal of Marriage and Family 70, no. 4: 919–33.

Charles, Kerwin Kofi, and Erik Hurst. 2003. “The Correlation of Wealth across Generations.” Journal of Political Economy 111, no. 6: 1155–82.

Cockerham, William. 2011. Sociology of Mental Disorder. 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

———. 2012. Medical Sociology. 12th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Collins, Chuck. 2012. 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality Is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do about It. San Francisco: Berrett-Koebler Publishers.

Congressional Budget Office. 2012. “The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2008 and 2009.” http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43373-06-11-HouseholdIncomeandFedTaxes.pdf (accessed September 1, 2012).

Domhoff, G. William. 2009. Who Rules America? Challenges to Corporate and Class Dominance. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Duncan, Greg J., and Richard J. Murnane, eds. 2011. “Introduction: The American Dream, Then and Now.” In Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances, 3–23. New York: Sage.

Edin, Kathryn, and Maria Kefalas. 2005. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood before Marriage. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Elder, Glen H., Jr. 1969. “Appearance and Education in Marriage Mobility.” American Sociological Review 34, no. 4: 519–33.

Elmelech, Yuval. 2008. Transmitting Inequality: Wealth and the American Family. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Ermisch, John, Markus Jantti, and Timothy Smeeding. 2012. From Parents to Children: The Intergenerational Transmission of Advantage. New York: Sage.

Forbes, John Hazard. 2010. Old Money America: Aristocracy in the Age of Obama. New York: iUniverse.

Frank, Robert H. 1999. Luxury Fever: Why Money Fails to Satisfy in an Era of Excess. New York: Free Press.

———. 2007. Richistan: A Journey through the American Wealth Boom and the Lives of the New Rich. New York: Crown.

Freeland, Chrystia. 2012. Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else. New York: Penguin.

Frey, Bruno S., and Alois Stutzer. 2002. Happiness and Economics: How the Economy and Institutions Affect Well-Being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1958. The Affluent Society. New York: Mentor Press.

Gilens, Martin. 2012. Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Grusky, David B., and Tmar Kricheli-Katz, eds. 2012. The New Gilded Age: The Critical Inequality Debates of Our Time. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hacker, Jacob S., and Paul Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer—and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Havens, John J., and Paul G. Schervish. 2003. “Why the $41 Trillion Wealth Transfer Estimate Is Still Valid: A Review of Challenges and Comments.” Journal of Gift Planning 7, no. 1: 11–15, 47–50.

Higley, Stephen R. 1995. Privilege, Power and Place: The Geography of the American Upper Class. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Joulfaian, D., and M. O. Wilhelm. 1994. “Inheritance and Labor Supply.” Journal of Human Resources 29: 1205–34.

Kalleberg, Arene. 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York: Sage.

Kalmijn, Matthijs. 1998. “Intermarriage and Homogamy: Causes, Patterns, Trends.” American Review of Sociology 24:395–41.

Kalmijn, Matthijs, and Henk Flap. 2001. “Assortative Meeting and Mating: Unintended Consequences of Organized Settings for Partner Choices.” Social Forces 79:1289–1312.

Keister, Lisa A. 2000. Wealth in America: Trends in Wealth Inequality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kendall, Diana. 2008. Members Only: Elite Clubs and the Process of Exclusion. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kerbo, Harold R. 2006. World Poverty: Global Inequality and the Modern World System. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Lareau, Annette. 2011. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Layad, Richard. 2005. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. London: Allen Lane.

Levine, Linda. 2012a. An Analysis of the Distribution of Wealth across Households, 1989–2010. Congressional Research Service, July 17, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33433.pdf (accessed September 1, 2012).

———. 2012b. The U.S. Income Distribution and Mobility: Trends and International Comparisons. Congressional Research Service, March 7, 2012. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42400.pdf (accessed September 1, 2012).

Massey, Douglas S., Jonathan Rothwell, and Thurston Domina. 2009. “The Changing Bases of Segregation in the United States.” Annals, American Academy of Political and Social Science 626:74–90.

McNamee, Stephen J., and Robert K. Miller Jr. 1989. “Estate Inheritance: A Sociological Lacuna.” Sociological Inquiry 38:7–29.

———. 1998. “Inheritance and Stratification.” In Inheritance and Wealth in America, ed. Robert K. Miller Jr. and Stephen J. McNamee, 193–213. New York: Plenum Press.

MetLife Mature Market Institute. 2010. Inheritance and Wealth Transfer to Baby Boomers. Westport, CT: Mature Market Institute.

Miller, Robert K., Jr., Jeffrey Rosenfeld, and Stephen J. McNamee. 2003. “The Disposition of Property: Transfers between the Living and the Dead.” In Handbook of Death and Dying, ed. Clifton D. Bryant, 917–25. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mishel, Lawrence, Josh Bivens, Elise Gould, and Heidi Shierholz. 2012. The State of Working America. 12th ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Mishel, Lawrence, and Natalie Sabadish. 2012. “CEO Pay and the Top 1%: How Executive Compensation and Financial-Sector Pay Have Fueled Income Inequality.” Inequality and Poverty, Economic Policy Institute. http://www.epi.org/publication/ib331-ceo-pay-top-1-percent (accessed January 8, 2013).

Moynihan, Daniel Patrick, Timothy M. Smeeding, and Lee Rainwater. 2004. The Future of the Family. New York: Sage.

Murray, Charles. 2012. Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960–2010. New York: Crown Forum.

National Center for Health Statistics. 2011. Health, United States, 2011 in Brief. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

New York Times. 2006. As quoted in an interview reported in “In Class Warfare, Guess Which Class Is Winning,” by Ben Stein, November 26, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/26/business/yourmoney/26every.html (accessed August 30, 2012).

Ng-Baumhackl, Mitj, John Gist, and Carlos Figueiredo. 2003. “Pennies from Heaven: Will Inheritances Bail Out the Boomers?” Washington, DC: American Association of Retired Persons Public Policy Institute.

Norton, Michael I., and Dan Ariely. 2011. “Building a Better America: One Wealth Quintile at a Time.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 6, no. 9: 9–12.

Oliver, Melvin L., and Thomas M. Shapiro. 2006. Black Wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. 10th anniversary ed. New York: Routledge.

Parker, Kim. 2012. “The Boomerang Generation Feeling OK about Living with Mom and Dad.” Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/03/15/the-boomerang-generation (accessed September 1, 2012).

Peltzman, S. 2009. “Mortality Inequality” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23, no 4: 175–90.

Pew Economic Mobility Project. 2011. “Does America Promote Mobility as Well as Other Nations?” Pew Charitable Trusts. http://www.pewstates.org/research/reports/does-america-promote-mobility-as-well-as-other-nations-85899380321 (accessed January 14, 2013).

Phillips, Kevin. 2003. Wealth and Democracy: A Political History of the American Rich. New York: Random House.

Rosenfeld, Jeffrey P. 1980. Legacy of Aging: Inheritance and Disinheritance in Social Perspective. Norwood, NJ: ABLEX.

Rosenfeld, Michael J. 2008. “Racial, Educational and Religious Endogamy in the United States: A Comparative Historical Perspective.” Social Forces 87, no. 1: 1–31.

Salverda, Weimer, Brian Nolan, and Timothy M. Smeeding, eds. 2009. Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sauls, Adam. 2012. A Longitudinal Study of American Economic Elites. Unpublished MA thesis, University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Schervish, Paul G., Platon E. Coutsoukis, and Ethan Lewis. 1994. Gospels of Wealth: How the Rich Portray Their Lives. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Schnittker, Jason. 2008. “Diagnosing Our National Disease: Trends in Income and Happiness, 1973 to 2004.” Social Psychology Quarterly 71, no. 3: 257–80.

Schwartz, Christine, and Robert D. Mare. 2005. “Trends in Educational Assortative Marriage from 1940 to 2003.” Demography 42, no. 4: 621–46.

Schwartz, T. P. 1996. “Durkheim’s Prediction about the Declining Importance of the Family and Inheritance: Evidence from the Wills of Providence, 1775–1985.” Sociological Quarterly 26: 503–19.

Sherwood, Jessica Holden. 2010. Wealth, Whiteness, and the Matrix of Privilege: The View from the Country Club. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Sieber, Sam D. 2005. Second-Rate Nation: From the American Dream to the American Myth. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Smeeding, Timothy, Robert Erikson, and Markus Jantti, eds. 2011. Persistence, Privilege and Parenting: The Comparative of Intergenerational Mobility. New York: Sage.

Smith, James P. 1999. “Healthy Bodies and Thick Wallets: The Dual Relation between Health and Economic Status.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 13: 145–66.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2012. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future. New York: Norton.

Taylor, John. 1989. Circus of Ambition: The Culture of Wealth and Power in the Eighties. New York: Warner Books.

Thurow, Lester C. 1999. Building Wealth: The New Rules for Individuals, Companies and Nations in a Knowledge-Based Economy. New York: HarperCollins.

United for a Fair Economy. 2012. Born on Third Base: What the Forbes 400 Really Says about Economic Equality and Opportunity in America. Boston, MA. http://faireconomy.org/sites/default/files/BornOnThirdBase_2012.pdf (accessed January 24, 2013).

U.S. Department of Labor. 2012. “National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2011 (Preliminary Results).” Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cfoi.pdf (accessed January 14, 2013).

Van Leeuwen, Marco, Ineke Mass, and Andrew Miles, eds. 2006. Marriage Choices and Class Boundaries: Social Endogamy in History. International Review of Social History Supplement 13. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge.

Weitz, Rose. 2013. The Sociology of Health, Illness, and Health Care: A Critical Approach. Boston: Wadsworth.

Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Willenbacher, Barbara. 2003. “Individualism and Traditionalism in Inheritance Law in Germany, France, England, and the United States.” Journal of Family History 28, no. 1: 208–25.

———. 2012. “The Asset Price Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class.” New York: New York University.

Wilson, William Julius. 1987. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wolff, Edward N. 2010. “Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze—an Update to 2007.” Working paper no. 589, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

———. 2012. “The Asset Price Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class.” NBER Working paper no. 18559. The National Bureau of Economic Research.

Zissimopoulos, Julie M., and James P. Smith. 2011. “Unequal Giving: Monetary Gifts to Children across Countries and over Time.” In Persistence, Privilege and Parenting: The Comparative Study of Intergenerational Mobility, ed. Timothy Smeeding, Robert Erikson, and Markus Jantti, 289–328. New York: Sage.

Zweigenhaft, Richard L., and G. William Domhoff. 2006. Diversity in the Power Elite: How It Happened, Why It Matters. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.