CHAPTER 5

THE NOVEL

PART ONE: CHARITON

Sleep and agency

The Greek novels owe much more to Homer than to Apollonius of Rhodes. Though Jason shares traits with novelistic heroes – he is engaged to be married, is often dejected and is extraordinarily handsome – there is almost no evidence that the novelists drew inspiration from the Argonautica. The only certain allusion to it is one passage in Chariton's Callirhoe in which Chaereas, like Jason, is described as a dazzling star.1 On the other hand, Chariton quotes Homer obsessively, echoes Homeric phrases and refashions Homeric episodes. Other novelists likewise exploit Homeric epic, though they tend to refer to it more indirectly.2 They are also indebted to Homer in their treatment of sleep and sleeplessness, as is especially perceptible in the earliest extant novel, Callirhoe, and the latest, the Aethiopica. At the same time, a great number of influences other than Homer contribute to enrich the sleepscape (if I may) of the ancient novels in specific ways. This final chapter will focus on each novel's distinctive responses to Greek traditions of thinking about sleep, as well as on their shared traits in their exploitation of sleep and wakefulness to construct their plots, themes and characters.

Chariton is fond of initiating momentous events with restless nights. A night ‘filled with worries’, in which all the involved parties are wakeful, precedes the launching of Mithridates' scheme to help Chaereas recover his wife (4. 4. 4); the transference of Callirhoe from the hands of the pirate Theron to those of Dionysius' servant Leonas is framed by ‘a night that seemed long to both, for the one was in a hurry to buy, the other to sell’ (1. 13. 6); the tomb robbery that leads to the heroine's kidnapping is decided upon in a sleepless night, when Theron, Odysseus-like, engages in an internal monologue to put together his plan (1. 7. 1–3); and on yet another such night, the same character ponders how to handle his prisoner, who is too beautiful to be sold to a commoner and will make him and his band undesirably conspicuous. After wasting much time,

When night came he was not able to sleep, but said to himself: ‘you are a fool, Theron. You have left silver and gold behind in a solitary place for so many days, as if you were the only robber. Don't you know that there are other pirates sailing the sea? And I am also worried that my own may leave me, and sail away. Certainly you have not enlisted the most upright of men […] Now’, he said, ‘you must rest, but when day comes, run to the cutter and throw the woman into the sea […]’ When he dozed off he dreamt he saw locked doors, and decided to wait that day.

(1. 12. 2–5)

The sequence ‘sleeplessness followed by a nap with a significant dream’ goes back to Homer (in Odyssey 4 and 20). A common denominator in the Homeric episodes is that the dreams accord with the sleepers' wishes.3 In contrast, Theron's vision pushes him to revise his decision to kill Callirhoe and run, telling him that he cannot depart and pursue his plan (the doors are locked). In this respect, the episode calls to mind one in Herodotus (7. 12–8) in which a recurring dream compels Xerxes to adopt a plan he had discarded earlier. Disquieted by the advice of Arbatanus, he spends part of the night in thought and decides not to attack Greece (as Theron decides not to sell Callirhoe). When he falls asleep, however, a handsome man appears to him and urges him to reconsider. He does not, but the vision recurs, and when Arbatanus wears Xerxes' clothes and dozes on his couch, the dream appears to him as well and tells him that the war ‘is fated to happen’. The late hour brings Xerxes good judgement (night is called εὐφρόνη, which in antiquity was explained as a coinage from εὖ-φρονεῖν, ‘to have good thoughts’),4 but sleep, which seems to follow from his decision to refrain from war (he is serene and slumbers deeply: καθύπνωσε), harms him by carrying the war-instigating dream. Theron's sleep, which also seems to descend from the tranquility he has reached after making his decision to depart, is similarly harmful to him.

One function of Theron's dream is to avert the foreclosure of the plot via a non-novelistic ending (Callirhoe's death). Another is to undermine his agency, suggesting that he is not entitled to direct the plot as he wishes and revealing that ‘Providence’ (as it will be called later) is already shaping events against his plans, just as ‘fate’ was shaping those in Persia against Xerxes' better judgement. While Theron's decision to rob Callirhoe's tomb, the outcome of his sleepless thinking, marks his initial control of the plot, his decision to wait, under the influence of a dream that nullifies his sleepless thinking, foreshadows his exit from the plot as a director, as an active player and soon as a player of any kind. The locked doors ultimately portend his capture and failure to escape.

Callirhoe likewise dreams after prolonged wakefulness at a major turning point. The discovery that she is pregnant by Chaereas causes her to stay up, in deep thought (2. 9. 1): should she abort or raise the child?

So she was absorbed in such reasoning all night long. For a brief moment sleep came over her. An image of Chaereas stood near her, like him in every way, ‘similar in stature and beautiful eyes and voice, and wearing the same clothes’ (Il. 23. 66–7). He stood and said, ‘my wife, I entrust you with our son’. He wanted to say more but Callirhoe leapt up, eager to embrace him. Thinking that her husband had advised her, she decided to raise the child.

(2. 9. 6)

Like Theron, Callirhoe receives an orienting dream. But her heart and mind are in line with it. Though she is undecided, her maternal instinct seems to prevail from the outset. This is made clear by the ordering and length of the speeches with which she weighs her options. In her internal debate the argument for keeping the child has the last word, and it is twice as long as the one in favour of abortion; moreover, it contains a passionate vision of a bright future in which the family is reunited (2. 9. 2–5). In addition, the choice of Patroclus' dream vision as a model for Chaereas' suggests that Callirhoe, like Achilles, is willing to do what the vision tells her. Both dreams shake the dreamer with their requests, but in both cases the request matches the dreamer's dormant or unconscious desire.

The synergy of Callirhoe's dream with her sleepless pondering underscores the fact that she is now seizing control of her life, in contrast to the passivity she has shown so far. Before this scene of internal debate she has had no say in the most momentous events that have befallen her. She does not know who it is she is marrying, then she is ‘killed’, and when Theron kidnaps and sells her she cannot take any initiative. Though she refuses to give her body to Dionysius, she cannot leave or move on in any other way. And even her success in keeping herself pure greatly depends on Dionysius' unwillingness to force himself on her. Lamentations, prayers, requests and prudent words are her only modes of action.

Sleep twice signifies Callirhoe's passivity. She is not responsible for her first, deep slumber, which is taken for death and evokes to the bystanders the sleep of the abandoned Ariadne (1. 6. 2). The heroine has no active role in her unconscious state (contrast Anthia in Xenophon's novel, who is also the victim of an apparent death but because she tries to kill herself), but it initiates the novel's adventures, in spite of her. And when she sleeps again, her fate has just been decided. Left alone in Leonas' house after he and Theron have concluded the sale, she bemoans her misfortune until a restoring slumber ends her weeping and the first book: ‘So was she lamenting when at last sleep came upon her’ (ὕπνος ἐπῆλθεν).

There can hardly be any doubt that Chariton is here alluding to, or rather citing, Homer.5 The phrase rings Homeric. Compare Od. 4. 793: ‘So was she [Penelope] pondering when […] sleep came upon her (ἐπήλυθε […] ὕπνος)’ and Od. 12. 311: ‘While they [Odysseus’ comrades] were weeping […] sleep came upon them (ἐπήλυθε […] ὕπνος)'.6 Even the rhythm rings Homeric, for, if we count the last syllable of the preceding word, ἐπράθην (‘I was sold’), it is a dactylic hexameter: -θην. τοιαῦτα ὀδυρομένῃ μόλις ὕπνος ἐπῆλθεν.7 Chariton often sprinkles his prose with almost-iambic sequences (a debt to New Comedy),8 but he does not habitually reproduce hexametric patterns. The ending of Book 1 thus stands out as a Homericizing line embedded in his prose.

Specifically, Chariton might be echoing the coming of sleep to Penelope at Od. 4. 793, the line that resembles his phrase most closely.9 The novelistic book ending also resonates with other Homeric episodes in which Penelope, worn out by mourning, rests at last thanks to Athena and in sleeping loses touch with the plot. Like Penelope, Callirhoe is kept out of the action. She calls the room in Leonas' house ‘another tomb, in which Theron has locked me up’ (1. 14. 6), and this expression of her feelings links the sleep that engulfs her there to the unconscious state that caused her first entombment. She is no more in control of her fate now than she was then. Her slumber conveys her lack of agency.

Callirhoe's sleep in both of these episodes is dreamless. The first time she dreams is when she discovers her pregnancy, and Chaereas' image encourages her impulse to raise their child. From then on, at night she has visions that draw her nearer to what is happening by making her aware of events and shaping her mood and actions. When Chaereas is sold and put in chains, she dreams of him in chains and asks him to come to her (3. 7. 4); shortly thereafter, during a formulaic ‘brief nap’ following a sleepless night, she sees his ship burnt, as has actually happened, and herself trying to help him (4. 1. 1), and again on the eve of the trial in Babylon (5. 5. 5) she dreams of seeing him, as she indeed does the next day, and of their wedding, which indeed will be celebrated again after their definitive reunion.

I would suggest that the change in the nature of Callirhoe's sleep, from empty to full, from a blank space to a site of activity, occurs when she discovers her pregnancy because only then does she begin to behave like a true agent. The discovery, though framed by a comment on the tyranny of Fortune, ‘against whom alone human reasoning is powerless’ (2. 8. 3), forces Callirhoe to take her destiny into her own hands. The terms λογισμός and λογίζεσθαι, in the sense of ‘reasoning to make a decision’, characterize her behaviour only after she finds out her pregnancy (2. 9. 6; 2. 11. 4), whereas earlier, when the same words are (rarely) applied to her, they simply suggest that she is ‘trying to understand’ what is going on (1. 8. 2; 1. 9. 4), without taking any active role in it. Though she is manipulated into choosing to remarry by Dionysius' servant Plangon, her decision stems from her choice to raise the child and is ultimately her own.10

Callirhoe's new role as an active player in conjunction with her pregnancy is also reflected in her unprecedented and repeated wakefulness. She forsakes sleep two nights in a row. On the first she dozes only for the brief moment in which Chaereas' image guides her thoughts, and on the second she stays up, absorbed in her cares after a whole day of pondering: ‘She spent that day and night in such reasoning and was persuaded to live not for her sake but for the child's’ (2. 11. 4). Her final decision to raise the child and marry Dionysius issues from a whole day and night of thinking.

The transition from Book 2 to Book 3 brings out Callirhoe's enhanced agency by means of parallels and contrasts with the previous book transition. At both junctures a servant (Leonas, Plangon) goes off to Dionysius, both times to bring him a happy message (Leonas that he has bought a beautiful woman for him, Plangon that the beautiful woman wants to marry him), and both times Callirhoe is left behind in her room. But at the end of Book 1 she is slumbering and has decided nothing, while in Book 2 she is awake, having determined her own fate over the course of a sleepless night.11

Rewriting Penelope's sweetest slumber

While Callirhoe's first dream orients her action, all the others carry outside happenings into her mind. In Artemidorus' classification they are ‘theorematic’, visions of objective events external to the dreamer (though Callirhoe's feelings violently break into her dreams).12 One other character is granted a theorematic dream: the noble and noble-minded Dionysius.13 Before he meets or even hears of Callirhoe, he tells his servant, who has hurried back to him at night to bring news of the slave he has acquired, that for the first time since the death of his first wife ‘I have had a pleasant sleep (ἡδέως κεκοίμημαι), for in my dream I saw her clearly: she was taller and more beautiful, and was with me as if she were really there (ὡς ὕπαρ)’. The servant breaks in: ‘You are lucky, sir, both in you dream (ὄναρ) and in reality (ὕπαρ)’ (2. 1. 2–3).

This scene is a Homericizing pastiche. The dream harks back to Penelope's vision of Odysseus (in Odyssey 20) quite precisely. Both seem real (ὕπαρ) to the dreamers, both come physically close to them and in both the dead or lost spouse has an enhanced appearance. Furthermore, Dionysius' admission that he has rested well for the first time recalls a similar comment made by Penelope in Odyssey 23, when she calls her sleep the most pleasant since her husband left. Chariton cues the reader to the reference by ascribing Homeric ‘sweetness’ to sleep only this one time in the entire novel.

There is a difference, though: Penelope's best slumber is dreamless, while Dionysius' is filled with a wonderful vision. It is actually the vision that causes his sleep to be sweet. This reversal of Penelope's experience, as well as of a more general pattern of thought, according to which the best sleep is dreamless,14 seems to be related to the more optimistic and sentimental bent of the novelistic character. Penelope is happy while she dreams of Odysseus lying beside her, but upon awakening she hates the vision because it is at variance, or so she thinks, with her harsh reality. She does not let the happy dream spill over into her grim waking world, even if the dream seemed true enough (ὕπαρ). Dionysius, in contrast, is ready to let his blissful vision colour his experience of sleep upon awakening.

Chaereas' rivals, sleepless from love

Dionysius' sweet sleep is soon replaced by love-induced insomnia. A rare specimen of insomnophobia in Greek literature, he knows he will not be able to rest on the night of his fatal encounter with Callirhoe, and so he protracts his drinking to stay awake with his friends. When he breaks up the party, we enter his bedroom, where he still

Could get no sleep but was entirely in the temple of Aphrodite and remembered everything, her face, her hair, how she turned, how she looked at him, her voice, her bearing, her words […] Then you could see a contest between reason and passion. For, although drowned by desire, he tried to resist like the noble man he was […] saying to himself: ‘Are you not ashamed, Dionysius, the first citizen of Ionia in excellence and reputation […] of this childish passion?’

(2. 4. 3–4)

Dionysius is the first character in the novel to be shown sleepless because of love. It is true that sleep disturbances do also affect the protagonists after their encounter: ‘When night came, it was terrible for both’ (1. 1. 8). Chariton, though, does not dwell on their agony, but hurriedly moves on. His choice fits his novel's narrative tempo, fast at the beginning. Chariton treats the onset of love briefly because he wants to get the story going. He is not interested in the preliminaries to the adventures that separate the lovers, only in the adventures themselves. On the other hand, when Dionysius appears on the scene, the adventures are well underway and the narrative pace is slower.15 The time is ripe for a theatrical display of sleepless torment.

An additional reason Chariton emphasizes the rival's insomnia over that of the protagonists might be the authority of tradition. In Greek literature prior to the novel, sleepless lovers are alone in their suffering. Their passion is and will be either unrequited or much stronger than the sentiment the other feels for them. Medea is sleepless, not Jason; Dido, not Aeneas; the lover in Plato's Phaedrus (251e1–2), but not the beloved, not even when he returns his own, paler, affection (255d–e). An epigram by Meleager features a wakeful lover sending a buzzing mosquito to his beloved, with this message: ‘He is waiting for you, sleeplessly. But you, forgetful of lovers, slumber’.16 The contrast between the lover's insomnia and the carefree repose of those who do not love is reproduced in this image of sleeping Eros, indifferent to the restless pain he causes: ‘You slumber, you who bring sleepless cares to mortals’ (AP 16. 211. 1).

The novels change this state of affairs. They attribute lovesick insomnia to both the hero and the heroine, thus highlighting the reciprocity and identity of their passion.17 Chariton, however, seems to follow the tradition by privileging unloved lovers as the victims of attacks of sleeplessness. Dionysius suffers from one such attack again during his journey to Babylon. Gnawed by jealousy, he regrets having left Miletus, where ‘he could have slept holding his beloved in his arms’ (4. 7. 7).18 And the Persian king Artaxerxes spends three nights awake, thinking of Callirhoe.

The sun has long set when Artaxerxes makes his momentous decision to summon Callirhoe to Babylon. Urged in a letter to put Mithridates on trial, since he is purportedly guilty of trying to seduce Dionysius' wife, the king spends the day in consultation with his friends, to no avail. But ‘when night came’ (4. 6. 6), he decides for the trial.

And another feeling pushed him to send for the beautiful wife as well. Wine and darkness had been his advisers in his loneliness and reminded him of that part of the letter [which praised the beauty of Dionysius' wife]. He was also goaded by the rumour that a certain Callirhoe was the most beautiful woman in Ionia.

(4. 6. 7)

The decision-making process in this scene reverses the Persian custom of taking counsel first at night, while drunk, and then by day, when sober (Hdt. 1. 133). The reversal makes Artaxerxes' political deliberations susceptible to extra-political motives, fuelled by the influence of counsellors – darkness, wine and solitude – that stimulate erotic imaginings. The scene foreshadows his gradual slide from king to lover, which, as we shall see presently, is mirrored in the content of his sleeplessness.

The eve of a second trial, which will adjudicate whether Chaereas or Dionysius is to be Callirhoe's husband, finds the royal couple entertaining opposite thoughts. The queen is looking forward to the new day as a chance to get rid of the beautiful Callirhoe; but not so the king:

He stayed awake all night, ‘lying now on his side, now on his back, now on his face’ (Il. 24. 10–1), reflecting with himself, and said: ‘the moment for the decision has come […] Consider what you should do, my soul. Decide with yourself. You have no other counsellor. Eros himself is a lover's counsellor. First, answer to yourself: are you Callirhoe's lover or her judge? Don't fool yourself!’

(6. 1. 8–10)

Artaxerxes resembles Dionysius insofar as both offer a theatrical display of sleepless agony. But their performances differ. With Dionysius on stage the spectacle we watch (or rather hear) is a dramatic contest (ἀγών), a psychomachy. The words he utters are those of reason fighting passion and upholding honour and dignity, the words of a ‘philosophizing’ soul (2. 4. 5) desperately trying to get the better of love. The Persian king makes no such attempt. The detail that his wife is by his side and suspicious of him (6. 1. 6) builds an appropriate frame for his display of adulterous passion. As soon as he enters the stage, his desire comes into full view in the unruly movements of his body. While Dionysius' sleeplessness is, as it were, bodiless, Artaxerxes is exposed as he tosses and turns like Achilles during the insomniac nights in which he longs for Patroclus. Artaxerxes' words do not restore his dignity. Whereas Dionysius vocally rebukes himself for his indulgence in love, Artaxerxes vocally endorses his and gives up his role of judge. Far from enacting an ἀγών between passion and reason, he fills his monologue with imagined voyeuristic pleasures. He addresses his eyes, calling them ‘miserable’ if they can no longer take delight in the ‘most beautiful spectacle’ that Helios ever ‘saw’ (6. 1. 9–10) and measures his passion by his pleasure in seeing Callirhoe: ‘You do not admit it, but you love. You will be further convicted when you will see her no more’ (6. 1. 10). He thus alleges a dream and postpones the trial, wanting to at least keep the woman in Babylon to be the object of his ‘gazing’ (6. 1. 12), for the pampering of his eyes.

The next day Artaxerxes confides his passion to his eunuch, who faced with Callirhoe's impregnability, seeks to persuade him to stop his pursuit. He does stop, but only until sunset:

Again when night came he burnt. Eros reminded him of Callirhoe's eyes, the beauty of her face; he praised her hair, her way of walking, her voice, how she looked when she entered the courtroom, how she stood, her speech, her silence, her embarrassment, her tears. Artaxerxes was wakeful most of the night and slept only long enough to see Callirhoe even in his dreams.

(6. 7. 1–2)

The opposition between daytime distractions and night-time fixation shapes the king's behaviour. Like Homer and Sophocles, the Greek novelists know that the pains of the heart are sharper at night, when activity stops.19 The king's resurgence of desire marks a crescendo compared to its display in the first episode of sleeplessness. For then he dwelt only on Callirhoe's ‘beauty’ (6. 1. 10), with no detail, while now her features, movements, postures, behaviour and voice come alive in his mind one by one. The fantasy prolongs the daydream he had during a hunt, when ‘He was seeing Callirhoe alone, though she was not there, and hearing her, though she was not speaking’ (6. 4. 5). The imaginary picture that he ‘moulded’ (ἀναπλάττων) then (6. 4. 7) fills the hours of darkness and fashions a real dream.

No other character in Callirhoe is as often described in nocturnal agitation. This privileging of Artaxerxes underscores his double role as king and as lover. As king, he is fitted, even expected, to spend wakeful nights absorbed in thought, in the manner of epic or tragic rulers. To say ‘thinking of my people, I cannot sleep’ is a mark of good leadership, as the weak leader Jason demonstrates by appealing to the cliché when he seeks to obtain confirmation of his role.20 Chariton certainly knew the topos from earlier literature, first of all from his cherished Homer. Moreover, the dream's reproach to Agamemnon in Iliad 2, ‘rulers cannot sleep all night’, had become something of a proverb by the first centuries AD. The phrase is treated as a maxim in the scholia;21 it is quoted in the essay On Homer attributed to Plutarch (2. 1915–6); it is familiar to the Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria (Pedagogue 2. 9. 81. 4) and it appears in a third-century textbook of rhetoric, Hermogenes' Progymnasmata, which in an exercise asks the pupil to develop the thesis ‘to sleep all night does not become a man who takes care of many things’.22 Those words were also taken to support the belief that the hours of darkness are the best time to deliberate.23 Eustathius uses the dictum to shore up his explanation of εὐφρόνη, a post-Homeric epithet of the night, as ‘bringing good counsel’.24

We first meet Artaxerxes in the grip of a difficult decision, which he is not able to make in the daytime but can make with the help of counsel-bringing night. Though the darkness and the wine instigate a voyeuristic impulse, his decision is still mostly political (4. 6. 6) and summoning Callirhoe is an afterthought. Eroticism plays only a surreptitious role, by enticing the curiosity of a king who is used to having every beautiful thing, women included, at his disposal (6. 3. 4). The second decision he makes in a sleepless night is caused entirely by desire, but still results in a public proclamation in which he issues public orders, as king, while the third is a recantation of his politically wise resolution to stop his pursuit and results in a secretly manoeuvred attempt at seduction. The comparison with Achilles, while eroticizing the epic hero's insomnia,25 also brings out the purely private and emotional causes of Artaxerxes'.26

The three episodes that show Artaxerxes sleepless thus build a sequence in which political responsibility increasingly yields to desire. Dreams participate in revealing this erotic escalation. On the first night Artaxerxes' still openly defensible decision is not influenced by a dream; on the second his erotically motivated actions are covered up by the kind of dream that would be expected of a ruler27 and on the third his inability to rein in his passion spills over into an erotic dream that extends his sleepless fantasizing. The king turns into a lover, and his night-time quandaries point up this shift in role.

They told stories and made love: but did not sleep

One evening Chaereas, who has successfully fought for the Egyptians and against the Persian king, decides to approach the beautiful, unknown prisoner of war, who turns out to be Callirhoe. After public celebrations of their reunion, the two retire, exchange stories, then ‘gladly came to the old rite of the bed’, like Odysseus and Penelope (8. 1). The reference to the Homeric couple foregrounds one aspect of the novelistic episode that is often noted: more than just a reunion, it is a second wedding – rather, the true wedding, crowned by lovemaking. The narrative of the nuptials in Syracuse does not cross the threshold of the couple's bedroom. Unlike Xenophon, who devotes an exuberant description to the wedding night and its rituals,28 Chariton does not go beyond the public ceremony. His choice might once again be related to the initially fast pace of his novel, which runs towards the decisive incident (Callirhoe's ‘death’). Nonetheless, by skipping over the wedding night and moving lovemaking to the night of the reunion, Chariton suggests that the wedding only truly happens, or happens ‘with more honour’ (5. 9. 3), after the trials have been completed.29

In one meaningful detail, however, the novelistic duo does not imitate its Homeric model. While in the Odyssey the night of love ends in a rewarding, limb-loosening slumber,30 the novelistic couple is not said to rest. A restorative sleep would have been psychologically and even physically justified for them, in the case of the heroine perhaps even more so than for her epic counterpart.31 Both Chaereas and Callirhoe have been tried for a long time, up until the very day of their reunion. He has just fought an epic war, she has just borne up with capture and imprisonment and has been so distressed that she has refused to eat. Why don't they fall under Hypnos' spell?

We could invoke narrative reasons for sleep's absence: Chariton might have wished to undercut the finality of the scene of reunion because the couple's dangers are not over. Their threat becomes real on that very night, for the sudden arrival of a soldier causes the couple's bedroom to be opened to let him in (8. 2. 2) – and the action to restart, with pressing urgency. But the Odyssey does not end with the end of dangers, either, yet it allows the couple to rest temporarily from their ongoing trials. Chariton could have adhered to his model in this, using the sequence ‘sleep followed by a new beginning with renewed dangers’.

The failure of limb-loosening slumber to descend on the novelistic duo highlights not so much the dangers that still loom as the priority of the romantic element. Love has the last word. This is a feature Callirhoe shares with the other two novels that describe the protagonists in their passionate intimacy, the Ephesiaca and Daphnis and Chloe, in neither of which does sleep follow lovemaking. The novels' plotline – two young people falling in love and, after a number of trials, starting a life together – is at variance with marital sleep. No novelistic pair can find happiness in resting side-by-side. None is seasoned enough to imitate Odysseus and Penelope, who, even after twenty years of separation, desire sweet slumber rather than being, like the protagonists of Longus' novel, ‘more sleepless than owls’.32

More specifically, the absence of sleep from the scene of reunion in Callirhoe also contributes to the characterization of Chaereas as a responsible military leader as well as a loving husband. The loving husband, eager to be with his wife, takes care of doing for himself what Athena does for Odysseus: he lengthens the night. While he used to spend all his time on the military ship, busy with many things, after recovering Callirhoe he entrusts everything to his friend and ‘without even waiting until evening, he entered the bedroom’ (8. 1. 13). But the night he plans to extend is curtailed on the other end: ‘It was still night when an Egyptian of high rank landed’ (8. 2. 1). He asks where Chaereas is, insisting that he will speak only to him. So his friend opens the door, and ‘Chaereas, like a good general, says, “summon him in. War tolerates no delay”’ (8. 2. 2). Chariton's hero imitates the historian Xenophon, who, in the flattering self-portrait he draws in the Anabasis, is always ready to be approached, at breakfast and dinner, and to be awoken (4. 3. 10). Chaereas is playing two roles: as a happy (at last) lover and husband, he hurries to the bedroom while it is still daylight, but as a capable commander, he is ready to get up before daylight on the happiest night of his life.33

PART TWO: XENOPHON OF EPHESUS

Sleepless with love's agonies and joys

Sleeplessness has a more limited presence in the Ephesiaca than in Callirhoe. Xenophon's characters do not stay awake to make decisions. In one instance the novelist sketches a scene of quandary that might have continued through the night, when Anthia, after killing the would-be rapist Anchialus, ‘takes counsel with herself over many things’. What should she do? Commit suicide? But Habrocomes might still be alive. Leave the cave where she is imprisoned? But the journey is impossible. ‘So she decided to stay in the cave and bear up with whatever god might choose’ (4. 5. 6). The decision amounts to taking no initiative and sleeplessness follows the dilemma rather than containing it: ‘That night, then, she waited, without sleep and with much in her thoughts’ (4. 6. 1). Anthia's wakefulness is not caused by the urgency she feels to solve her predicament but by her inability to do so.

Love-induced insomnia is more to Xenophon's taste than nightlong pondering. Neither the hero nor the heroine can rest after their fatal encounter: ‘When they went to sleep, their misery was complete, and love in both could no longer be contained’ (1. 3. 4). We hear first Habrocomes bemoaning his state, then Anthia. The protagonists' sleeplessness is filled not just with words but also with visions: ‘So each of them lamented the whole night. They had each other before their eyes, and their souls were moulding (ἀναπλάττοντας) each other's image. When day came…’ (1. 5. 1)

Xenophon expands on Chariton's simple phrase ‘that night was terrible for both’ by dwelling on the two protagonists serially, in keeping with his penchant for narrative doublets.34 He also modifies Chariton in his distribution of insomnia. Instead of devoting a full narrative to the rivals' and only a passing comment to the protagonists', the Ephesiaca lavishes sleepless drama on the protagonists and never attributes sleep disturbances to any rival. The reversal is consonant with a reversal in narrative pace: Xenophon's novel runs almost breathlessly through the core of the adventures but relates their preliminaries very slowly, above all, the encounter between the hero and the heroine.35 While in Chariton it takes up less than a paragraph, in Xenophon it covers two pages; while in Chariton love flares up casually, at a narrow crossing (1. 1. 6), in Xenophon its ignition is anticipated by the crowd's comments on the protagonists' beauty (‘what a wonderful pair they would make!’), by their desire, spurred by those comments, to see each other and by the solemn setting of love's attack, a religious ceremony in which Habrocomes and Anthia parade their beauty and keep looking at each other (1. 3. 1–2). Their nocturnal fantasies prolong the intensity of their first visual contact.

By peeping into the protagonists' bedrooms and showing them not only as they pour out their despair but also as they indulge in visions of each other, Xenophon underscores the sensuality of their mutual attraction. The night-time exposure of their passion agrees with their uninhibited behaviour at their first encounter. The girl is not modestly covered and silent, but makes herself heard and shows as much skin as she can: ‘with contempt for maidenly decency, she said something for Habrocomes to hear, and bared the parts of her body she could for Habrocomes to see. He gave himself to the sight and was the captive of the god’ (1. 3. 2). The two play their daring act under the public eye, with a ‘whole crowd’ as witness (1. 3. 1), and when they part, they keep each other's image in mind. Their mutual desire increases all day (1. 3. 4) until night brings more erotic imaginings. Xenophon's hero and heroine have the kind of fantasies that Chariton assigns to the rivals, both in the daylight (Callirhoe 6. 4. 5–7, where the same verb ἀναπλάττειν appears) and in their sleepless nights (2. 4. 3; 6. 7. 1).

The strong desire that keeps Anthia and Habrocomes awake is soon shared and satisfied on their wedding night, which both harks back to and reverses the miserable night of their encounter. Habrocomes connects them: ‘O most desired night, at last I have you, after so many unhappy nights!’ (1. 9. 2) Again, we hear him first (1. 9. 2–3) and then Anthia (1. 9. 4–8), but while he plays a greater role in the lamentation scene, she does on their night of love.36 The summary phrase that concludes the first episode is echoed and modified in the account of the second: ‘they lamented the whole night […] and when day came’, turns into ‘the whole night they rivaled each other, both eager to show that they loved the other more. When day came’ (1. 9. 9–10. 1). Xenophon's hero and heroine release the erotic tension that filled their first sleepless night (and many more) on another wakeful night, at the end of which they have that unmistakable glow on their faces: ‘When day came, they got up much happier, much more cheerful, after giving each other the pleasures they had desired for so long’ (1. 10. 1). There is no such image of post-coital contentment in Chariton's more Homericizing novel.37

Sleepless while everyone slumbers

Like sleeplessness, sleep plays a smaller role in Xenophon than in Chariton. In both it is primarily a vehicle for dreams, but in Chariton it also comes to end insomniac nights, in Homeric fashion, whether carrying visions or not. When it does carry visions, in Chariton it advances the plot, either by pushing a character's decision in or against the direction it was taking during hours of restless rumination or by causing an involuntary action (as when Callirhoe, sleep talking, calls Chaereas' name aloud, leading Dionysius to discover that she was married before [3. 7. 4]). Sleep in this novel is also an instigator of the plot in the case of Callirhoe's Scheintod (‘apparent death’), which causes her kidnapping.

In Xenophon, only Anthia's corresponding Scheintod elevates sleep to a motor of the action. She is buried, and tomb robbers find her when she has just awoken, and then sell her (3. 6–9). But this plot-advancing sleep replaces an intended death. Anthia is the only novelistic protagonist who commits suicide. To keep herself for Habrocomes when an unwanted marriage is impending, she manages to obtain a drug and drinks it on her wedding night. She sets out to follow the tragic topos of ‘marriage to death’ (as in Antigone, Hecuba, and Iphigenia in Aulis), without knowing, as the readers do, that death will be replaced by slumber (3. 6. 5) because the drug is not a poison but a hypnotic, fitting to adapt the tragic topos to the novelistic rule that the heroine cannot die.38

Apart from this episode, sleep has little impact on the novel's development, even as the vehicle for dreams. Dreams can influence mood39 but do not inspire actions, except in one instance – in which, however, the action instigated by the vision would kill the heroine. Anthia sees herself with Habrocomes in the early days of their love, but another woman appears, also beautiful, and drags him away; as he screams and calls Anthia by name, she awakens (5. 8. 5). Believing the dream to be true, she despairs, thinking that Habrocomes has betrayed their oaths of mutual fidelity, and seeks a means to die.

Anthia' dream is connected to two of Callirhoe's: the one in which she sees Chaereas, in chains, trying to come to her but unable to do so (3. 7. 4), and the one in which she relives the beginnings of their love and the wedding day (5. 5. 5–6).40 The first vision seems echoed in a phrase found verbatim in both accounts: ὄναρ ἐπέστη, ‘a dream stood upon her’ (Ephesiaca 5. 8. 5; Callirhoe 3. 7. 4), while the second is behind the setting of Anthia's dream in the early days of her love. Though in her vision the chains that appear in Callirhoe's first dream are replaced by another woman (betraying Anthia's obsession with betrayal?), Habrocomes behaves like a prisoner who screams to be freed, as Chaereas does. Anthia's belief that her vision reflects reality also recalls Plangon's conviction that Callirhoe's dream of her wedding day corresponds to reality (Callirhoe 5. 5. 7). If Xenophon had this dream in mind, he reversed its purpose: while Callirhoe is heartened by her vision, Anthia's makes her mood take a turn for the worse. The dream, if acted upon, would dispose of the novel's heroine. The one action prompted by it would again be suicide.

Though sleep plays a minor role in the Ephesiaca, it is sometimes used in a manner not found in Chariton: to bring the intensity of one party's activity to the fore, providing a backdrop for episodes of sleeplessness or nocturnal action. Two of these episodes involve the flight of a character. Here is the first: ‘Then they [Hippothous and his band] slept all night, but Habrocomes was thinking of everything, Anthia, her death, her tomb, her disappearance. No longer able to restrain himself, he pretended he needed something and exited without being seen (for Hippothous’ band was lying prostrated by drink), and leaving them all he went to the sea' (3. 10. 4). The second episode further stresses the repose and stillness of the surroundings. Hippothous kills his rival at night, in his sleep, ‘and when all was quiet and everyone was resting, I left just as I was, without being seen […] and travelled the whole night to reach Perinthos, and immediately we boarded a ship […] and sailed to Asia’ (3. 2. 10–1).

These episodes are variations on the lonely vigil motif. The first begins in the same vein as the typical lonely vigil, with everyone slumbering except one person, who is beset by worries. In both narratives the restful background enhances the desperate state of emergency in which the fleeing characters find themselves. In contrast, a third episode with sleep as its background is the happiest in the novel: the protagonists' intimate celebration of their reunion. The scene is configured as an atypical lonely vigil, one in which, as perhaps in no previous Greek specimen, the intense activity of the wakeful party is joyful rather than anguished. The protagonists celebrate together with their newly recovered friends, then all retire, Leucon with Rhode, Hippothous with his boyfriend and Anthia with Habrocomes:

And when all the others had fallen asleep and there was complete quiet, Anthia, embracing Habrocomes, wept: ‘my husband’, she said, ‘and master, I have found you after much wandering on land and at sea. I have escaped threats of brigands, plots of pirates, insults of pimps, chains, ditches, fetters, poisons and tombs, and I have come to you […] as I was when I was taken from Tyre to Syria. […] And you, Habrocomes, have you stayed chaste? [...]’ Thus saying she kept kissing him. […] The whole night they made such protestations to each other and easily persuaded each other, since this was their desire. […] When day came, they embarked.

(5. 14. 1–15. 1)

Structural, thematic and linguistic parallels tie this night to the two earlier sleepless nights experienced by the protagonists. Sleep is forsaken ‘the whole night’ each time, and each time the new day is said to come, in the same words (the phrase ‘the whole night they did this […] and when day came’ appears in the last instance as well).41 The two culminating episodes in the early stages of the plot – the encounter and the wedding – are recalled in the culminating episode at the end.

Xenophon, however, makes the third scene more climactic. While in the first two the protagonists' wakefulness has no background, in the final one it stands out against a landscape of sleepers. The novelist might have had in mind the reunion of Odysseus and Penelope, which is accompanied by a general cessation of activity and by the retiring of Telemachus and of Odysseus' loyal servants (Od. 23. 297–9).42 In Homer, though, sleep does not frame the entire narrative of the couple's reunion, only the portion that follows lovemaking, in which Odysseus and Penelope tell their stories and then doze off in turn. Furthermore, Homer does not enhance the restful atmosphere created by sleep with a statement that ‘there was complete quiet’. The added emphasis provided by Xenophon further detaches the wakeful lovers and their words and actions from their soundless surroundings.

Of the extant novelists Xenophon is the only one who stages three full-blown scenes of sleeplessness for his protagonists – one filled with love's pains, one with love's pleasures and one with protestations of love's permanence – to punctuate the main steps in their shared erotic journey. As we shall see in the next section, Achilles Tatius stands diametrically opposed to Xenophon, in that he allots sleepless nights only to his hero, and fills them only with love's pains.

PART THREE: ACHILLES TATIUS

Clitophon's overblown insomnia

Except for its frame, Achilles Tatius' novel is told in the voice of the protagonist, Clitophon.43 The heroine's feelings at their first encounter remain unknown because the hero chooses not to disclose them, even though he might be aware of them at the time when he is telling his story. In contrast, he offers an inflated narrative of his own experience of love's onslaught, with its attendant sleeplessness. He starts off by giving a full account of the night following his encounter with Leucippe: ‘When evening came, the women went to bed first, and soon afterward we did the same. All the others had received enough pleasure from their bellies, but my own feast was all in my eyes: I was filled with the unadulterated vision of the maiden's face, and, sated with it, I left drunk with love. But when I reached the room where I was used to sleeping, I was unable to find sleep’ (1. 6. 1–2). Diseases and bodily wounds, he continues, are worse at night because we are at rest and can feel them more intensely. Likewise the wounds of the soul cause more pain when the body does not move. In the daytime ears and eyes are busy with many things that distract us, but ‘when stillness binds the body, the soul, alone with itself (καθ᾽ἑαυτὴν γενομένη), swells with its woe. For all that was lately asleep awakens (ἐξεγείρεται)’: pains, worries, fears, fire (1. 6. 2–4).

Clitophon's account of his sleeplessness is affected by his tendency to embellish the experience of the acting character with intellectual flourishes.44 The alleged woes of the restless lover give the narrator the opportunity for a sententious explanation that does not ring true to the character's raw experience. Clitophon dresses up the commonplace that worries and pains are worse at night by alluding to the Platonic view that the body's slumber empowers the soul to see true reality (Resp. 571d–572b). The philosopher claims that sleep, for those who do not overindulge in their appetites but ‘awaken (ἐγείρας) their rationality’ and ‘treat it to beautiful words and thoughts’ before bedtime, will allow the soul to be ‘pure and alone with itself’ (αὐτὸ καθ᾽ αὑτὸ μόνον) and ‘apprehend something it does not know’.45 Clitophon echoes Platonic imagery and language (ἐξεγείρεται, καθ᾽ἑαυτὴν γενομένη)46 but distorts Platonic doctrine. He goes to bed filled not with beautiful thoughts but with a vision of the beautiful girl, and he does not awaken his rationality but suffers the awakening of his passion.

When at last Clitophon dozes off, the image of the young woman does not leave him: ‘all my dreams were of Leucippe: I talked with her, played with her, ate with her, touched her, and obtained more happiness than in the day. For I kissed her, and the kiss was real’ (1. 6. 5). The narrator continues his erudite and playful dialogue with Plato. While the Platonic rational soul will grasp truths during the body's slumber and have dreams that are ‘the least lawless’ (Resp. 571b1–2), the novelistic lover has a dream that is lawless indeed. Finally, love poetry steps in to further glamorize his account: ‘As a result [of the dream], when the servant awoke me I scolded him’ (1. 6. 5). Clitophon tops off his narrative by hinting at the epigrammatic motif of the lover upbraiding a songbird for awakening him while in the embrace of an erotic dream.47 The wealthy, urban novelistic hero devolves this unpleasant role to his servant.

Clitophon's insomnia apparently does not abate. Its effects are manifest on his face three days later, when he confides the nature of his love to his cousin Clinias and asks for his help: ‘he [Clinias] kissed my face, which showed a lover's sleeplessness, and said, “you love, you really love: your eyes tell the tale”’ (1. 7. 3). Before Clinias can offer his advice, however, his beloved Charicles rushes in and breaks into their conversation with the awful news that he will be married off. When he leaves, Clitophon still complains of his insomnia: ‘I cannot bear the pain, Clinias. Love in all its power is over me, and drives even sleep from my eyes. I have imaginings of Leucippe everywhere’ (1. 9. 1). Clitophon works mentions of his insomnia into a narrative entrelacement, interrupting his confession with the sudden appearance of Charicles and resuming it with intensified pathos after his departure. His complaint of sleeplessness is drawn out by the intervening episode, after which it restarts in a louder voice. The extension and escalation have the effect of amplifying the account of his misery.

But why does Clitophon draw so much attention to his insomnia? His taste for scholarly display might be partly responsible for his lengthy first description of it, but not for his repeated complaints to Clinias. Instead, as Clitophon reports the conversation, he wants the reader to appreciate the ravages caused by his torment. His efforts seem to be aimed at portraying himself as the perfect specimen of the novelistic lover, who outdoes his colleagues in suffering love's pains. Clinias (whose words, of course, could be made up) confirms Clitophon's tale, thus functioning as ‘evidence’ of its truthfulness and pushing the readers to give credence to it.48

At the same time, however, Clitophon's account reveals the erotic proclivities of a young man unabashedly interested in sex, who dreams of touching and kissing the girl he desires on the very first night of his acquaintance with her.49 No other hero or heroine of a Greek novel has erotic dreams, except for Daphnis and Chloe, who once dream of lying together naked, making up for their daytime shyness (2. 10). But in their case the vision is innocent, because they do not know what sex is and are applying a lesson in love remedies. The erotic dream that prolongs Clitophon's sleepless night, already haunted by Leucippe, rather recalls Artaxerxes' vision in Chariton, which also prolongs a sleepless night haunted by the image of the desired woman. The portrait of a romantic hero's lustful rival thus looms behind the image of Clitophon, whose dream – more daring than Artaxerxes', filled as it is with fondling and kissing – looks ahead to the more advanced overtures that he will soon attempt in his waking hours.

Clitophon's emphasis on his sleeplessness has further implications. To the second-time reader (or to the reader who has reached the end of the novel), it suggests from the outset (or in retrospect) that in this novel the imbalances caused by love, among which is sleeplessness, are the story; that there is no satisfying compensation for them.

The day of the reunion ends in a manner atypical of the genre and unsatisfying both for the protagonists and for readers accustomed to more conventional romances: with sleep in a temple. Leucippe retires after reassuring her father about the virginity test she is mandated to take (8. 7. 2–5), and the next day, once her virginity has been proven, the company retires to bed ‘in the same way as before’ (8. 18. 5). The hero and the heroine obviously have to spend these nights apart, because they are not married and the girl's father is present. But they could have stayed awake in their separate quarters, longing for each other and for their marriage, or at least they did not have to go to sleep ‘in the same way as before’. Both episodes are, as in Homer, only caesurae in the action, which resumes with exactly the same words after each night: ‘On the following day…’ (8. 7. 6; 8. 19. 1) This routine, formulaic rhythm of sleep and activity de-romanticizes the lovers' recovery of each other and substitutes for their wedding night, which is not narrated.

The replacement of the wedding night with a drawn-out reunion that includes two episodes of sleep supports an extreme interpretation of the story's ending: that the marriage turned out to be unhappy.50 As a matter of fact, Clitophon does not look like a happily married man when he tells his story, but bears the mark of his initiation into love, visible on his face (1. 2. 2). His eyes still ‘tell the tale’, as they did when he confessed his sleepless love to Clinias (1. 7. 3). His enduring disquiet could explain his choice not to dwell on that special night, which should have repaid him for his loss of sleep, but does not seem to have done so. The prolonged frustration manifested in his allegedly prolonged insomnia found no relief in a night filled with lovemaking.

Hypnotics

Clitophon's erotic dream at the end of his first sleepless night comes true. He manages to kiss and fondle Leucippe and plans to meet later in her bedroom. The operation requires precautions, for her doorkeeper, Gnat (Κώνωψ), is a busybody, true to his name, who buzzes all over to watch the young man's actions closely. To clear the way, Clitophon's conniving servant Satyrus buys a potent sleeping drug, invites Gnat to dinner and pours the drug into his last drink. The doorkeeper is scarcely able to make it to his bedroom, where he ‘fell down and lay, sleeping a drugged slumber’ (2. 23. 2–3). With Gnat disposed of, Clitophon walks ‘on tiptoes’ (ἀψοφητί) into Leucippe's room, following a maid. To no avail, for Leucippe's mother Panthea, shaken awake by a frightening dream, bursts in. Clitophon sneaks out just in time.

Drugged sleep furthers the couple's manoeuvres once more. To avoid facing their families, the two decide to elope. When all is ready, Satyrus drugs Panthea with the rest of the potion he had used for Gnat, pouring it into her last drink. She leaves for her room and ‘was immediately asleep’. Satyrus proceeds to dispose of Leucippe's chambermaid and the doorman in the same way. And ‘when everybody was slumbering’, they leave ‘on tiptoes’ (ἀψοφητί) and reach the harbour, where they hurriedly board a ship about to set sail (2. 31).

Of the extant Greek novels, Leucippe and Clitophon is the only one that exploits drugged sleep to remove an obstacle and advance the lovers' plans. When, in Xenophon, Anthia drinks a sleeping potion, she thinks it is a poison and uses it against herself. Two characters in the same novel, Habrocomes and Hippothous, flee unnoticed while everyone rests, but they do not drug people to get their way: in each case, the repose that provides the background for the escape is natural.51 In Achilles Tatius, by contrast, sleep is artificially induced and individually targeted to allow the lovers to act secretly.52

The two episodes made possible (or almost) by drugging opponents underscore Clitophon's cowardliness.53 In the first he is an anti-Odysseus:54 he needs his slave even to put his enemy to sleep, and when all is ready and the slave tells him, ‘Your Cyclops lies asleep: you prove yourself a good Odysseus!’ (2. 23. 3), he enters Leucippe's room ‘trembling a double tremor’ (2. 23. 3–4). In the second episode Satyrus and Clinias, not Clitophon, organize the flight and take the risks. The servant visits Leucippe, dopes everyone, leads the maiden by the hand (her lover cannot even do that!) and opens the doors, while Clinias arranges for a carriage to wait for them.

Along with pointing up Clitophon's lack of courage, the use of drugs to dispose of an obstacle gives the two scenes a flavour of low literature. Hypnotics put to similar use are a favourite feature of folktales (‘guardian magically sent to sleep while girl goes to lover’ is an entry in Stith Thompson),55 beginning with the folktale of Odysseus and the Cyclops. Drunken slumber provides a means of escape also in a mime (preserved in a first-century AD papyrus) in which a Greek girl, Charition, can flee from the clutches of an Indian king because her liberators intoxicate him during a ceremony.56 To change cultural landscape, drugged sleep used to get the better of an enemy appears in Mozart's Entführung aus dem Serail, where the pasha who keeps Constanze as his favourite concubine is knocked out by fortified wine to allow her and her lover to meet, if not to escape. The engineer of the trick is a servant, as in Achilles Tatius.57

There is a difference, though, between these episodes and those in Leucippe and Clitophon. In folktales and mime, doped sleep not only fosters the organizers' plans but also works towards the expected ending: Odysseus must blind the Cyclops; Charition must escape. This is not the case for the first novelistic scene, in which the drug helps the lovers with a plan – to have sex outside of marriage – that must not come true, for it would steer the novel's plot irremediably away from generic expectations. The trick cannot fully succeed as in the corresponding folk motif ‘guardian sent to sleep while girl goes to lover’.

The flight episode does not contravene generic expectations. On the contrary, it initiates the outward journey that is the precondition for and the container of the expected adventures. But the flight also leaves Clitophon and Leucippe unguarded and thus free to have sex, as was their wish. Detailed echoes of the scene in which they attempt to do so set the reader's mind on the possibility that they might make good on their wish. The drug used in the second scheme is what is left of the one used in the first; Panthea drinks it with her ‘last cup’, as Gnat does with his, in the same words (she κατὰ τῆς κύλικος τῆς τελευταίας, and he κατὰ τῆς τελευταίας κύλικος); both retire and doze off instantly (though we appreciate the writer's more respectful treatment of the lady: she does not ‘fall down […] sleeping a drugged slumber’ like the slave but ‘is immediately asleep’); both Clitophon entering Leucippe's room and the actors in the escape move ‘on tiptoes’, and Leucippe is led by Clitophon's servant (2. 31. 3), just as Clitophon in the earlier scene is led by Leucippe's maid (2. 23. 3). The interlocking of the two episodes casts the elopement as the substitute for the failed night of sex, keeping the doors open for sex to be consummated on the road and for the plot to deviate again from generic parameters.

In both episodes, Achilles Tatius sends a dream to counter the lovers' schemes and bring the plot back on the expected track. In the first instance Clitophon and Leucippe cannot carry out their plan because Panthea's nightmare prevents them. In the second they do manage to escape, but a parallel dream forbids lovemaking, against their desire (4. 1. 4; 4. 1. 5). Whether injunctive or predictive, dreams restore generic norms or suggest that those norms must prevail, functioning as antidotes to the lovers' attempts to transgress novelistic protocols with the help of hypnotics.

Sleep, the cure for all illnesses

Leucippe and Clitophon is unique among the extant Greek novels in entrusting characters not only with sleeping potions to remove obstacles, but also with love potions to attract the objects of their desire. Melite seeks to procure a love philter to charm Clitophon, and Gorgias brews such a drug to compel Leucippe. If the narrative is to be an ideal novel, however, these potions must not accomplish their goals; otherwise, the genre's Rule #1, ‘I shall love you and only you’, would be shattered. The drug would transfer love to new couples, producing plots in which the rivals would succeed at making the hero or the heroine return their affection. Achilles Tatius does not go this far. Just as he counters the protagonists' plans to have sex, he nullifies their rivals' attempts to destroy their attachment through drugs. Melite does not obtain the philter, and Gorgias' potion does not do what it was supposed to do, for Leucippe is given too strong a dose and becomes insane instead of falling in love. (In passing, is Achilles Tatius mocking the Platonic conception of love as madness?)

The narrative of Leucippe's illness contains another type of sleep without parallel in the other novels: sleep artificially induced for healing purposes. The doctor summoned to treat the girl explains to Clitophon that he will give her a hypnotic before administering the therapy: ‘We shall make her slumber to quiet the savagery of the crisis, now at its peak. Sleep is the cure for all illnesses’ (4. 10. 3). Clitophon sits by her all night, talking to the chains that restrain her. When she awakes, she cries out senseless words. The doctor gives her the second medicine, but to no effect.

‘Sleep, the cure for all illnesses’: this is a commonplace in Greek culture.58 The novelistic doctor follows this widespread belief in sleep's healing power, which had also been codified in medical writings since at least the late fifth century.59 But medicinal slumber this time does not help, for Leucippe awakens as deranged as she was; nor does the second drug help. Is there any point to this medical failure, besides the obvious one of prolonging the suspense by deferring resolution?

Leucippe's sleep eventually does provide the cure. After ten days of madness with no improvement, ‘once in her slumber, she uttered these words in her dreams:60 “It is because of you that I am mad, Gorgias!”’ (4. 15. 1) Achilles Tatius causes another dream, with the sleep talking it breeds, to move the action back to its novelistic track by restoring the heroine to sanity and to the hero. Gorgias' servant is eventually found and he promises to heal the girl. Following his instructions, Clitophon drugs her again, and while she slumbers he watches her as he had done the first time around. Verbal repetitions further connect the two scenes. Just as the doctor prescribes sleep ‘to quiet the savagery (τὸ ἄγριον) of the crisis’, Clitophon prays for the drug to ‘overcome that other barbarous and savage (ἄγριον) drug’ (4. 17. 1); on the first night, Clitophon asks the sleeping Leucippe, ‘are you in your senses (σωφρονεῖς) while you slumber or are even your dreams mad?’ (4. 10. 3), and on the second he says, ‘your dreams have sense (σωφρονεῖ)’ (4. 17. 4). By echoing the previous scene of uncured madness, Clitophon underscores the reversal.

The doctor's failure and the success of the unexpected sleep talking highlight the dominance of Chance, Tyche, in this novel. What brings about Leucippe's healing is a random utterance, prompted by no human or divine contrivance. The picture radically changes in Daphnis and Chloe, where Tyche plays no role in solving the protagonists' predicaments, but the gods do. And they use sleep and dreams as the chief means to reach their goals.

PART FOUR: LONGUS

Chloe's siesta

Daphnis and Chloe are taking a break from their shepherding duties during the hottest hour of the day. He is piping and the flocks are resting in the shade, when Chloe ‘dozed off unawares’. Daphnis notices it, stops playing and devotes himself to greedy contemplation of his Sleeping Beauty:

He looked (ἔβλεπεν) at all of her, insatiably, because he was free from shame, and as he did he softly whispered: ‘what eyes are slumbering there, what breath comes from that mouth! Not even apples or pears smell so sweet! But I shrink from kissing her: her kiss bites the heart, and like new honey it drives one mad. I am also afraid that my kiss might wake her. Oh those talkative cicadas, they won't let her sleep with all the noise they make! And those he-goats, banging their horns as they fight! Oh wolves more cowardly than foxes, can't you come to snatch them?

(1. 25)

This scene fits into a cultural landscape rich in images of sleepers. Starting with the Hellenistic period, sleeping figures become much more prominent than they had been in archaic and classical Greece, appearing often in paintings and making their debut in sculpture. New sleepers are pictured: in addition to Ariadne (Figure 5.1) and the maenads, Satyrs, Nymphs, the child Eros (Figure 1.2), Hermaphrodite and Endymion. A variety of settings host their images, including gardens and cemeteries.61 Epigrammatic poetry and Philostratus’ Imagines reflect these developments by describing sleeping figures, especially Eros and Ariadne,62 while the conceit of the lover watching his loved one slumbering appeals to poets and prose writers both Greek and Roman. Longus' vignette, which is part of a narrative that claims to ‘counter-write’ a painting (Proem 2), demonstrates the novelist's keen awareness of contemporary trends in art and literature.

The scene also looks back, to an episode from Plato's Phaedrus (259e1–6), which Longus' contemporary readers would easily have recognized because of the dialogue's popularity.63 Socrates and Phaedrus are conversing under a plane tree, in the midday heat, while the chirruping cicadas tempt them to sleep.64 Like the two friends in Plato's dialogue, Daphnis and Chloe are starting on a quest. But they are seeking love, not doing philosophy.65 The different goals of the searchers are also reflected in their different attitudes towards sleep.

Figure 5.1 Sleeping Ariadne, Roman copy of a Hellenistic sculpture (second century BC), Rome, Vatican Museums.

Socrates and Phaedrus cannot yield to the temptation of a nap, lest the cicadas consider them like lazy sheep and fail to recommend them to the Muse of their profession. The two must keep conversing so as to produce a countermelody against the cicadas' lulling song. In contrast, Daphnis and Chloe are not conversing to begin with, and they make no effort to stay awake. While he is playing, she slides into sleep without even noticing. The sluggish animals that in Plato constitute the negative example for the ever-wakeful philosophers reappear in Longus as the resting flocks that lead the way to Chloe's nap.66

Rather than imitating the unsleeping philosopher, Chloe resembles the epigrammatic figure of the worn-out lover who wishes to lull his passion to sleep with the help of a talkative insect, as in this poem by Meleager:

Ringing cicada, drunk with dewy drops, you sing your pastoral song that chatters in the wilderness, and seated on top of the leaves, striking your dark skin with saw-like legs, you make shrill music like the lyre's. But sing, friend, some new merry tune for the nymphs of the trees, strike up a loud sound in response to Pan, that I may escape from love and snatch a midday nap, reclining here beneath the shady plane tree.

(AP 7. 196)

Several components of Longus' vignette can be seen in this epigram: the shade (under a ‘Platonic’ plane tree), the midday hour and the cicada. Both this epigram and a second one, also by Meleager (AP 7. 195) and working with the same conceit, share with Longus' novel the additional motif of love-induced insomnia. Just as the lover who calls for the insect's lulling song wishes he could ‘snatch a midday nap’; just as he has been suffering, as reads the second poem, ‘from the toils of all-sleepless care’, Chloe has been almost chronically insomniac since she first felt the pangs of love (1. 14. 4; 1. 22. 3).

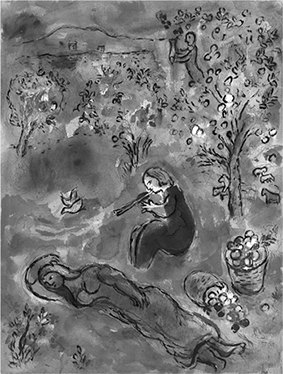

It is not an insect, however, that sends Chloe to sleep, as in the wish of the epigrammatic lover, but Daphnis' music. Longus implies this by framing the scene with the lad playing the panpipes rather than with the cicadas chirping in the trees, as in Plato. To be sure, talkative insects used to work their hypnotic charm on Chloe, but that was before she fell in love. ‘Who will take care of the chirruping cricket’, she says, ‘which I toiled much to catch so it could lull me to sleep […] Now I cannot rest because of Daphnis, and the cricket chirrups in vain’ (1. 14. 4). Daphnis' music alone has power, the only music that captivates her ears when she falls in love: ‘his panpipes make a beautiful sound, but so do the nightingales. Yet I do not care for those’ (1. 14. 2). Marc Chagall, who has illustrated the scene of Chloe's nap in his lithograph Midday in Summertime (Figure 5.2), puts the lulling charm of Daphnis' music front stage by drawing him not in the act of looking at Chloe but piping, while she seems to be about to fall asleep, for she is turned slightly sideways. The substitution of Daphnis' pipes for the chirping cicadas that tempt Socrates and Phaedrus to doze off illustrates the importance of music in Longus' representation of love's development.67

Figure 5.2 Marc Chagall, Midday in Summertime (1961), lithograph, from Daphnis and Chloe.

Chloe's sleep leads to a separation between the children, assigning them different roles shortly after their first, identical experience of love's onslaught. Before the nap scene they look at each other in the same way. For both, love acts as an eye-opener, causing them to see each other afresh. While at the bath, Daphnis ‘appeared beautiful’ to Chloe as she ‘contemplated’ his naked body (1. 13. 2). After the fatal kiss, Daphnis admired Chloe's face ‘as if only then for the first time he had acquired eyes, and until then he had been blind’ (1. 17. 3).68 A few lines prior to the nap scene, the children are still enjoying their habitual pleasure of looking at each other:

When midday came, their eyes were captured. She, seeing (ὁρῶσα) Daphnis naked, was entirely taken by his beauty and melted with love, unable to find fault with any part of him. And he, seeing (ἰδών) her with the fawn skin and the pine wreath as she handed him the pail, thought he saw (ὁρᾶν) one of the Nymphs in the cave.

(1. 24. 1)

Chloe's nap comes shortly after this scene and likewise it takes place at noon, but it reads like a new development against the previous episode. Daphnis and Chloe were accustomed to look at each other in wonder, midday after midday. But one midday she falls asleep, lulled by his music, and their mutual and identical seeing (ὁρᾶν) comes to an end, replaced by his individual and more voluntary act of vision (ἔβλεπεν): it is a ‘gaze’, that is, ‘a way of looking that is intense, focused, and demonstrative of agency’.69 Daphnis has gazed at Chloe before. Though the children discover each other's beauty with equal eyes, Daphnis behaves, or wants to behave, more actively: ‘he wanted to look (βλέπειν) at Chloe, but when he looked (βλέπων) he was filled with blushing’ (1. 17. 2).70 While Chloe slumbers, he can look at her without blushing, and he does so with a gaze that could even be called, following Longus' description of it, ‘consumptive’, because it rests unchecked and insatiable on the sleeping woman.

Cued by the author's emphasis on Daphnis' unrestrained way of watching Chloe, Longus' readers will instantly be reminded of the familiar image of a sleeper who becomes prey to lustful eyes – or more than just eyes. Sometimes, the lover does not even spend much time watching before rushing into action. In an epigram by Paulus Silentiarius (sixth century AD), for instance, the account of the erotic attack takes precedence over the description of the sleeper, which stops after mentioning the posture conventional for sleeping figures in art:

One afternoon pretty Menecratis lay outstretched in slumber with her arm twined around her head. Boldly I entered her bed and had to my delight accomplished half the journey of love, when she woke up, and with her white hands set to tearing out all my hair. She struggled till all was over, and then said, her eyes filled with tears: ‘Wretch, you have had your will’.71

In other instances the gaze becomes prominent. Thus in an epigram by Philodemus:

Moon of the night, horned moon, friend of all-night festivals, shine! Shine through the cracks of the window and illuminate golden Callistion. For an immortal goddess to spy on the deeds of lovers is no cause for reproach. You bless her and me, I know, Moon. For Endymion also set your soul on fire.

(AP 5. 123)

This lover parades a scopophiliac exhibitionism, asking the Moon, whom he imagines to be as voyeuristic as himself, to enter the bedroom and let her light shine, first on his girl, so he can watch her, then on their lovemaking.

Daphnis is as aroused as these lovers, and many more besides. However, he does not make the slightest move towards Chloe. And his gaze, his only ‘move’, turns out to be far more discreet than Longus announces by calling it insatiable and without shame. Most of Daphnis' soliloquy is occupied with his fear of kissing Chloe and his wish that she keep on sleeping. It is true that the longer she slumbers, the longer he can look at her. His expressed wish, that she should not awaken, hides an unexpressed wish for more undisturbed watching. But his preoccupation with his fear, rather than with her features, saves the girl from the exposure suffered by other sleeping women, who meet with a more expansive gaze. All we are given to see of Chloe through Daphnis' eyes are her own eyes and mouth.

Figure 5.3 Niccolò Pisano, An Idyll: Daphnis and Chloe (c.1500), London, The Wallace Collection.

This takes me to a second way Daphnis' gaze turns out to be more modest than is expected. The youth looks only at Chloe's face, countering the titillating expectations raised by Longus' introductory comment: ‘he looked at all of her’. Later painters have not missed the focus of Daphnis' gaze. So for instance Niccolò Pisano, in An Idyll: Daphnis and Chloe (Figure 5.3), points Daphnis' eyes towards the girl's face, while her breasts are exposed only for the pleasure of those viewing the painting. Even more concentrated on her face are the young man's eyes in a work by François Boucher (Figure 5.4), though Chloe's breasts are more lavishly displayed there than in Pisano's painting. Daphnis' contained gaze is consistent with the asymmetrical treatment of the children in the novel: while Chloe repeatedly sees Daphnis naked, he does not see her thus until the very end of Book 1 (32), when for the first time she bathes before his eyes. Until then, Chloe is always wearing something. Even in the narrative of their mutual watching and admiring of each other, which precedes the nap scene, she sees his naked body while he sees her wearing a fawn skin and a wreath.

Daphnis' contained gaze sets Longus' vignette in opposition specifically to this account of Dionysus approaching the sleeping Ariadne:

See also Ariadne, or rather her slumber. Her breasts here are naked down to her waist. Her neck is bent back and her throat is soft, and her right arm is totally visible while her left hand rests on her tunic to prevent the wind from dishonouring her. How her breath is, Dionysus, and how sweet, whether it smells of apples or grapes, you will tell me when you kiss her.

(Philostratus Imagines 1. 15. 3)

This episode is the main mythological inspiration for Longus' scene. The novelist and Philostratus may have worked from a common source.72 Both stress the care with which the bystanders try not to awaken the sleeper (see Imagines 1. 15. 2) and both include smell alongside sight as a sensual stimulus, in both cases the sweet, fruity smell of the woman's breath. Philostratus, however, undresses Ariadne. She is half naked and her body is front stage, while her face does not exist except for her enticing breath, to which Dionysus is lured. To prepare for the erotic contact, Philostratus adds the enticement of touch to those of sight and smell, drawing attention to the softness of Ariadne's skin. Daphnis neither sees nor feels Chloe's skin.

The absence of lustful intent makes Daphnis comparable to sleepwatchers, as Leo Steinberg has called the figures who gaze at sleepers in Picasso's graphic works of the 1930s. Sleepwatchers do not rush to their target but step back, absorbed in thought. A modern critic identifies the seeds of sleepwatching already in Greco-Roman art, in compositions in which a wakeful figure stands in awe and makes no move – not yet – towards the sleeper.73 Daphnis is likewise frozen in contemplation. The pause that sleepwatching creates, the suspension of action, is filled with his whispered monologue as he watches Chloe.

The reason for Daphnis' inaction, however, is not that the pleasure of contemplation reins in his desire. Rather, he is held back by his ignorance of love and is unable to read his desire, which he calls fear. Fear functions as the restraining force, both allowing Daphnis to keep his naïveté and causing him to abide instinctively by the generic and societal rules that he is required to follow in spite of his ignorance of them.

Daphnis' inability to understand his desire shows that he is still lagging behind Chloe in terms of erotic maturation. She is cast in the vulnerable position of the slumbering prey, but nothing happens to her, because Daphnis is unable to seize the opportunity afforded to him by her sleep. Conversely, when she awakens, she plays with his desire. After seeing that he took out of her blouse a cicada that had found refuge from a swallow there, she puts the insect back (1. 26). Chloe's gesture suggests that she understands, at least subliminally, what both she and Daphnis are seeking. But he does not seize this second opportunity to reach down to her breast again. Chagall catches Daphnis' naïveté in another lithograph, entitled The Little Swallow, in which Daphnis seems to avert his gaze shyly after taking the cicada out of Chloe's blouse.

Figure 5.4 François Boucher, Daphnis and Chloe (1743), London, The Wallace Collection.

The swallow, which looks like an innocent pet in Chagall's illustration, is a predator in Longus' novel.74 Its failure to seize the insect which Chloe's breast shelters thus foreshadows the gentle, non-predatory manner of her own erotic initiation. The swallow's defeat suggests that Daphnis, who does nothing to Chloe in the sleep scene, owing to his fearful ignorance, will abstain even when his ignorance is cured. His restraint finds a doubling in the restraint of the normally lustful god Pan, which is also announced in the sleep scene.

References to Pan crowd the episode. The choice of midday for Chloe's nap sets it in a landscape frequented by the god, who likes to make his appearances at noon and to doze in his pastoral haunts during the ‘immobile hour’, as Plato calls midday (Phdr. 242a4–5).75 Chloe's siesta may suggest Pan's own. Its Pan-like aura is enhanced by Daphnis' behaviour as soon as she falls asleep, for he stops playing, as if obeying the injunction of Theocritus' goatherd that one should not pipe at noon lest Pan awaken:

We're not allowed to pipe at midday, shepherd – not allowed.

We are afraid of Pan. It's then that he rests, you know,

Tired from the hunt: he is tetchy at this hour,

And his lip is always curled in sour displeasure.76

Another feature of the scene conjures up Pan: the hypnotic power of Daphnis' music. Two epigrams (AP 16. 12 and 13), purportedly inspired by a statue of Pan, represent him as he causes sleep with his piping: ‘Come and sit under my pine that murmurs thus sweetly, bending to the soft west wind. And see, too, this fountain that drops honey, beside which, playing on my reeds in solitude, I bring sweet slumber’. And: ‘Sit down by this high-foliaged vocal pine that quivers in the constant western breeze, and beside my bubbling stream Pan's pipe shall bring slumber to your charmed eyelids’. Pan lulls those who listen to his pipes to sleep, but when he himself dozes, piping must stop. Daphnis lulls Chloe to sleep with his pipes, but when she slumbers – in a setting evocative of Pan – he stops piping.

This cluster of allusions to Pan heralds his active participation in the plot. Though Longus' novel is ‘a dedication to Eros, the Nymphs, and Pan’ (Proem 3), only Eros and the Nymphs have intervened so far, taking concerted action in dreams (1. 7–8). Daphnis has invoked Pan in a beauty contest, but only as a self-serving comparison (1. 16. 3). It is towards the end of Book 1 that the god makes himself increasingly felt. The noon hour is the setting not only of Chloe's nap, but also, immediately before that episode, of the children's game of watching each other, and in the midday light Chloe is wearing a wreath of pine, a tree sacred to Pan, which Daphnis kisses and wears in turn, thus moving it to the forefront of the narrative (1. 24. 2).77 Immediately after Chloe's siesta, Pan makes his first meaningful appearance as an object of song, along with Pitys, a nymph he loved (1. 27. 2). The singer is a female cowherd who wears a pine wreath, like Chloe, and sits under a pine tree. Three sequences in close succession – the children watching each other, Chloe napping and the herdswoman singing – are thus sprinkled with references to Pan.