4

Homework Becomes You

The Model Minority and Its Doubles

The controversial memoir Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother opens with a list of activities forbidden to the author’s children: “attend a sleepover, have a playdate, be in a school play, complain about not being in a school play, watch TV or play computer games, choose their own extracurricular activities, get any grade less than an A, not be the No. 1 student in every subject except gym and drama, play any instrument other than the piano or violin, not play the piano or violin.”1 These lines provocatively set the banal quality of the restricted activities against the exceptional behaviors that were to be the norm. Author Amy Chua explains that these regulations were part of her efforts to raise her American daughters in what she calls “the Chinese way,” that is, with a firm hand (or, some would say, an iron grip) and an eye toward Carnegie Hall and the Ivy League.

When the Wall Street Journal published a preview excerpt of Chua’s book as “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior,” it triggered hundreds of angry comments from readers.2 I focus here on just two strands of this criticism, which help elucidate Asian American racial formation’s tendency to generate and close divides, to produce—as this chapter will elaborate—doubles as others and others as doubles. First, Chua’s implicit embrace of the model minority myth jarred with long-standing attempts to dislodge the perception that Asian Americans have triumphed over obstacles—racial or otherwise—through good values and hard work. Since the 1970s, scholars, community advocates, and artists have denounced the model minority stereotype, pointing to its damaging psychological and social effects. It has been linked to mental health issues among Asian American students, to political justifications for cutting welfare and affirmative action programs, and to increased tensions between minority groups, such as those explored in Chapter 3. In rejecting the stereotype, critics have emphasized socioeconomic differences among Asian Americans and drawn attention to communities whose struggles might be overlooked or discounted because of this racial preconception.

These communities constitute what one article calls “the other half”3 of the Asian American picture. “Asian-Americans: A ‘Model Minority,’” a story in Newsweek published in 1982, opens by establishing a clear dichotomy: “In this centennial year of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the assimilated anchorwoman and the unskilled member of an obscure Indochinese minority embody the extremes of the fastest-growing segment of the nation’s population.”4 In emphasizing a gap between the most successful Asian Americans and those who are at the very edges of American society, the article seems to ask whether the former are actually representative of Asian Americans in general. Yet insofar as the model minority myth promises that the latter can become just as successful, the persistence of struggling communities does not necessarily refute the stereotype; it can instead offer a useful image of what comes “before.” By always projecting ahead (from hardship to triumph), the model minority myth makes efforts to repudiate it a Sisyphean task.

Furthermore, as Susan Koshy and erin Khuê Ninh point out, not all who might identify as Asian American oppose their designation as the model minority.5 Some, such as Chua, regard it as a point of pride or a standard to emulate. From this perspective, examples of Asian Americans who do not fit the paradigm serve less to undermine the model minority myth than to drive it. In her memoir, Chua explains that in order to motivate her children, she invoked the experiences of first-generation immigrants, those who came with little money and never quite lost their outsider status. Revealing the class bias that informs the entire book, she limits her sample of first-generation immigrants to skilled workers and graduate students (20–21). Chua nonetheless recounts that she required her children to learn classical music because of her fear that they would exhibit signs of “third-generation decline” (i.e., “laziness, vulgarity, and spoiledness” [22]): “I knew that I couldn’t artificially make them feel like poor immigrant kids. There was no getting around the fact that we lived in a large old house, owned two decent cars, and stayed in nice hotels when we vacationed” (22). The everyday realities of the upper-middle-class family might embody the model minority as fait accompli, but do not offer the more grueling experiences of first- and second-generation immigrants, which ostensibly propel their hard work. Chua insists that hardship must precede success, and that the model minority cannot do without its others.

When these others actually appear in Chua’s book, however, their presence disrupts rather than facilitates her attempt to draw a line from her life to theirs. In her critique of Chua’s idealization of the economic limitations and social alienation of immigrants, Grace Wang argues, “To celebrate immigrant toughness as a privilege, cultural exclusion as a form of capital, and institutionalized racism and downward mobility as a personal challenge to succeed, allows us to turn racism into individual failure.”6 Wang points out that despite romanticizing these figures, “when Chua finds herself face-to-face with her fetishized immigrant subjects, she feels distance rather than affinity.”7 She cites Chua’s account of taking one of her daughters to audition for Juilliard: “In the waiting area, we saw Asian parents everywhere, pacing back and forth, grim-faced and single-minded. They seem so unsubtle, I thought to myself, can they possibly love music? Then it hit me that almost all the other parents were foreigners or immigrants and that music was a ticket for them, and I thought, I’m not like them. I don’t have what it takes” (142).

This moment, when Chua encounters those whom she had been seeking to emulate, evinces a contradictory mix of identification and dissociation. The distance that Wang observes is clear in Chua’s portrayal of the other parents as a crude Asian mass. Aesthetic appreciation seems impossible; music for them, Chua believes, is a financial investment. Yet what initially seems like a dismissal of the other parents becomes something else with the thought, “I don’t have what it takes.” Wistfulness suddenly exposes itself alongside condescension. If the difference Chua first describes is one that sets her above the other parents, their positions are soon reversed in her mind. According to her logic, because she is not a foreigner or a recent immigrant, she simply cannot compete with their determination. Chua reveals that for all her claims to be a “tiger mother” (and her dislike of drama as an extracurricular activity for her children), she is playing a role that she has studied and carefully put into practice. What forces a crisis in this performance is an encounter with her doubles: the “real” tiger parents.

Yet how does Chua determine that the other parents are the real thing? The pacing and grim faces might be suggestive, but certainly not enough to discern that they are “foreigners or immigrants.” Chua identifies something un-American or not-yet-American about the others, as well as something that reveals their need for a ticket, a meal ticket or a ticket to a better social status. One can only guess that Chua was assessing the other parents’ ways of speaking, behaving, and interacting, and finding them incongruous with her own. These differences presumably reflected back the inadequacy of her performance as a “Chinese mother,” even as they indicated to Chua the other parents’ inadequate performances of a particular cultural and social status that she might claim. The question nevertheless remains, how precisely do the textures of the mundane connect to actual material circumstances? And while Chua clearly sees herself as separate from the others, do they see her in the same way? If Chua had hoped to simulate the experiences of “foreigners and immigrants” while remaining distinct from them, their meeting forces a confrontation with an unverifiable difference, and a similarity that she both rejects and desires.

This brief scene in Chua’s memoir exemplifies a distinct form of Asian American doubling, one that also energizes director Justin Lin’s film Better Luck Tomorrow (2002) and Lauren Yee’s play Ching Chong Chinaman (first produced in 2008). An unlikely trio, these cultural productions all highlight the contradictory identifications prompted by the model minority stereotype. The model minority rarely goes without its “other half,” whether manifest as the yellow peril perpetually threatening the West, or as figures of economic and cultural alienation who seem to contradict the stereotype (or, according to Chua, to hold the secret to its perpetuation). If Asian American racial formation maintains a dichotomy between “good” and “bad” Asians, “good” and “bad” minorities, the double lives and alter egos that gradually take over Better Luck Tomorrow and Ching Chong Chinaman illuminate how this split can serve as a provocation to be like the other, and expose the complex system of incentives that compel such appropriations.

The film and the play, as well as a significant portion of Chua’s book, focus on Asian American teenagers who seem to typify the model minority. Like the accounts of Chinese immigrant laborers, Japanese “war brides,” and Korean American merchants examined in previous chapters, contemporary depictions of Asian American youths evince a fascination with the racial mundane—that is, with habitual, quotidian behaviors that come to exemplify the possibility and the limits of crossing racial boundaries. Since the 1980s, the apparent academic achievements of Asian American students have drawn attention to their daily practices as the potential source of their success. With an opening parallel to that of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, a New York Times article published in 1986 claimed to examine why, as the title observed, “Asians Are Going to the Head of the Class.”8 It begins, “Le Thi Ngoc, a 32-year-old computer technician in Fremont, Calif., follows a set schedule when she comes home from work. After preparing dinner, she spends the next two hours helping her 10-year-old son, Alan, with his homework. Alan is not allowed to watch television on weeknights, and if he plays with his G.I. Joe toys when he is supposed to be doing his schoolwork, his mother throws them away.”9 Like Chua, the writer stresses the regular schedules, dedicated hours, and restrictions on play that organize Alan’s days. Yet while this sketch of mother and son launches a story on the lack of consensus about why Asian American students are ostensibly doing so well—and then presents everything from genes to Confucian values to the background of the parents as potential explanations—Battle Hymn proposes that a strictly enforced routine of study and practice is the key.

The second, predominant strand of criticism directed at Chua focused on her defense of these parenting methods. Responding to the furor, Chua informed an interviewer that some readers found the book comforting: “Everybody wants to know why so many Asian kids are good at math and achieve so much, and many readers said, ‘This is such a relief: it’s not genetic, it’s not in the rice! It’s about hard work, so we can do this!’”10 The memoir, in Chua’s view, rejects the idea that achievement is the result of racial differences owing to genes or culinary preferences, and instead posits that success is the result of hard work, as embodied in everyday practices such as playing the piano for hours and doing extra exercises for school.

In narrating her readers’ steps toward revelation, Chua moves from genes to rice to work. Rice, as discussed in Chapter 1, became the focus of anti-immigration polemics, which claimed that it endangered the very substance of the nation: as a cheap alternative to meat, it fed (cheap) Chinese labor and threatened American vigor. Placed between genes and work in Chua’s account, rice bridges what seems purely bodily with what seems purely behavioral. It thus mediates the shift from race (Chinese mothers are superior) to practice (anyone can be a Chinese mother). While Chua celebrates the possibility of cultivating successful children through a change in habits,11 an anxiety not unlike the one that fed early efforts to restrict Chinese immigration pervaded conversations about her book. Time magazine succinctly put it, “Though Chua was born and raised in the U.S., her invocation of what she describes as traditional ‘Chinese parenting’ has hit hard at a national sore spot: our fears about losing ground to China and other rising powers and about adequately preparing our children to survive in the global economy.”12 Other publications captured these trepidations with titles such as “Tiger Cubs v. Precious Lambs.”13 Such responses, however, are hardly unique to Chua’s book. Earlier accounts of the achievements of Asian American students also characterized them as Asia’s challenge to American and Western dominance. The aforementioned 1986 New York Times article, for example, claimed, “suddenly they [successful Asian American students] seem to be everywhere,” and described, “they are surging into the nation’s best colleges like a tidal wave.”14 These images of startling growth and ubiquity imply a dangerous propagation through seemingly praiseworthy stories about Asian American youth.15 It is in this context that the title of the Pew Center’s 2012 report, “The Rise of Asian Americans,” takes on a more ominous tone.

In these depictions, long-standing fears of Asian masses (the yellow peril) converge with tales of unlikely success (the model minority).16 Koshy contends that while the model minority myth was initially engaged to counter demands, originating from the civil rights era, for domestic policies to address racial inequality, it has more recently come to express global economic concerns.17 She observes, “The model minority has become an anxious figure of the prized human capital needed to navigate the insecurities and volatility of the global knowledge economy.”18 In the slippage between “Asian” and “Asian American,” which Chua’s loose use of the term “Asian” perpetuates, the “tiger cub” comes to embody concerns that the United States will soon lose its economic edge to Asian countries. As both ideal and threat, the product of tiger parenting unites the model minority and the yellow peril. Arguing that these two figures, “although at apparent disjunction, form a seamless continuum,”19 Gary Okihiro points out that they can look more like twins than antitheses: “‘Model’ Asians exhibit the same singleness of purpose, patience and endurance, cunning, fanaticism, and group loyalty characteristic of Marco Polo’s Mongol soldiers, and Asian workers and students, maintaining themselves at little expense and almost robotlike, labor and study for hours on end without human needs for relaxation, fun, and pleasure.”20 Associated variously with an American work ethic, Confucian values, or an inhuman mechanical efficiency, the same model minority traits lauded for exemplifying American self-sufficiency can just as easily signify an un-American lack of playfulness, and even forebode the ascendance of Asia. The “tiger cub” then not only updates the model minority myth but also extends fears of the yellow peril, joining a line that includes “Marco Polo’s Mongol soldiers,” Fu Manchu, and, more recently, the figure of the Asian gangster.21

Chua’s detractors indeed seized on the very characteristics that Okihiro identifies as blurring the line between the model minority and the yellow peril. As Wang observes, “Parenting blogs reviled her mothering style as child abuse, pathologized the (narrowly defined) success achieved by Asian American kids as the product of excessive discipline and rote practice, and extolled the virtue of balance, sleepovers, and play.”22 In defending “Western” parenting, critics found fault in Chua’s practices and the kinds of children her practices presumably shaped. They asked, even if “tiger” mothers produced children better equipped for contemporary economic challenges, would that be the ideal outcome for Americans? Such concerns echo allegations in the late nineteenth century that white workers would have to eat rice, live in deplorable conditions, and otherwise lower their standard of living to compete with Chinese labor. Exemplifying a pattern documented throughout this book, the purported habits of Asian and Asian American children simultaneously embodied the promise and the threat of dissipating difference.

The stereotype of Asian youths as uncreative test-taking machines, used to rebuff Chua, makes a strange appearance in the memoir itself when she recounts that she did not want her daughters to turn into “one of those weird Asian automatons who feel so much pressure from their parents that they kill themselves after coming in second on the national civil service exam” (8). Chua suggests a desire to distinguish her ideal children from this stereotype, but implies that such perceptions of Asian students are accurate and that fears of propagating more automatons are warranted. Her description of the Juilliard waiting room, with “Asian parents everywhere, pacing back and forth, grim-faced and single-minded,” then renders these adults, with their robot-like determination, older versions of “those weird Asian automatons.” Just as responses to her memoir expressed fears of becoming and not becoming like the “Chinese,” Chua reveals her own ambivalent relationship to those whom she holds up as models when she encounters her “doubles” in the Julliard waiting room.

A persistent trope in Asian American cultural productions, the double surfaces in Chua’s memoir to express a fraught desire to identify (provisionally) with the model minority’s others. In Better Luck Tomorrow and Ching Chong Chinaman, the performances to which I now turn, the double becomes a means of critiquing as well as expressing this desire. In her seminal work on the “racial shadow” in Asian American literature, Sau-ling C. Wong cites numerous literary examples in which “a highly assimilated American-born Asian is troubled by a version of himself/herself that serves as a reminder of disowned Asian descent.”23 Building on psychoanalytical theories, Wong argues that this racial shadow elicits both “revulsion and sympathy” from the protagonist, who in “disowning” the double realizes their connection as much as their difference.24 Josephine Lee engages with Wong’s study to offer a modified view of the double in works of Asian American drama: she proposes that the double conveys not just a struggle within the psyche of Asian Americans, but “the interactions of Asian Americans caught up in myths of individual success promoted by a capitalist ideology.”25 Lee contends that while the Asian American characters in these plays initially reject ethnic ties in favor of individualism, their relationships with their doubles hint at ethnic affiliations that might offer an alternative to capitalist notions of self and other.26

The characters in Ching Chong Chinaman and Better Luck Tomorrow exhibit an impulse to reject associations with “Asianness” that recalls Wong’s study of the “racial shadow” and an acceptance of individualist notions of success that resonates with Lee’s analysis. Yet in these recent performances, attraction and wishfulness exert as strong a force in the production of doubles as the mix of repulsion and sympathy at the crux of Wong’s theory.27 Like the parents whom Chua encounters at Juilliard, these doubles are objects of envy and vehicles for furthering personal ambitions. Furthermore, unlike the plays examined by Lee, which suggest the oppositional potential of ethnic affiliations, Lin’s film and Yee’s drama link the double’s appeal to the contradictions of the model minority stereotype, which incentivizes both intimacy with and distance from those who seem to constitute the model minority’s others. These performances demonstrate both the longevity of the double in Asian American cultural productions and the new forms and meanings it has developed as a result of increasing divides within Asian America, a situation that Wong predicted would be “most conducive to formation of the double.”28

What I call the mundane, although not the focal point of Wong’s study, nevertheless emerges as a crucial facet of her argument when she shows in her reading of Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior that the double forces the Chinese American narrator to recognize “manner can be changed, but not skin color.”29 The racial shadow reveals, in other words, an apparent disjuncture between the narrator’s “race” (or what Robert E. Park might describe as her “racial uniform”) and her everyday behaviors. This dynamic is also evident in Better Luck Tomorrow and Ching Chong Chinaman, but quotidian enactments in these works serve more crucially to facilitate and constrain relationships between characters with model minority aspirations and the others who become their doubles. The former adopt different habits, exchange daily tasks, and generally stretch and manipulate the mundane to accommodate their desire to be another kind of Asian or Asian American. They thus attempt to take advantage of the ostensible paradox of Asian American racial formation, its vacillations between the yellow peril and the model minority, performing its inconsistencies to expand and change their lives. Yet they come to a point of crisis when confronted with those who reflect back the deficiencies of their performance, either by demonstrating its dependence on the affirmation of an unreliable audience or by revealing their material investment in privileges they seek to deny. Furthermore, the mundane, which initially seems to offer a way to double as the other, becomes a force of resistance when the lines between self and other become blurred.

Through various forms of doubling, Better Luck Tomorrow and Ching Chong Chinaman highlight the sharp economic stratifications that have come to characterize Asian America, stratifications that are alternately uncovered and covered over in debates about the model minority. They capture the fantasies and the anxieties generated by these divides, and the material and imaginative forces that compel as well as circumscribe crossings.

Playing the Part, Burying the Body

Heralded as a breakthrough work in Asian American cinema, the feature-length narrative film Better Luck Tomorrow became the center of controversy at the 2002 Sundance Film Festival.30 The film portrays a group of Asian American high school students who run scams, sell drugs, and hire prostitutes—when not applying to top universities and participating in respectable extracurricular activities like the Academic Decathlon. The film’s plot bears many similarities to the 1992 murder of teenager Stuart Tay in a suburb of Southern California. News stories dubbed the crime the “honor roll murder,” emphasizing the victim and the perpetrators’ reputations as good students and stimulating interest in the apparent inconsistency between this reputation and the grisly murder. While only loosely following the details of Tay’s death, Better Luck Tomorrow builds on the premise of studious Asian American teenagers who lead double lives.

During a postscreening discussion at Sundance, an audience member criticized the film as an amoral depiction of Asian Americans and asserted that the filmmakers had a responsibility to represent their community more positively. This comment in turn incited an angry response from film critic Roger Ebert, who countered that he would not have similarly reprimanded a white filmmaker. Asian American characters, Ebert insisted, “do not have to ‘represent’ their people.”31 In an article about the incident, he elaborated, “[Director] Justin Lin said he senses a moral disconnect in some of today’s teenagers and wanted to make a movie about it. His cast was all Asian-American because—well, why not?”32 Quoted in the same piece, Lin explained that the film reflected “a reality among teenagers of any race.”33

Although both the audience member and the film critic claimed to speak on behalf of Asian Americans and indicated that they recognized a history of racial discrimination, by giving precedence to either appearances or behaviors, they directed their accusations of racial insensitivity at separate targets. In other words, by privileging either how the characters in the film looked or how they acted, they located responsibility for racial identifications—or for color blindness—at different sites. The audience member suggested that given the visibility of the characters’ “race,” their behavior reflected badly on an entire community. Meanwhile, Ebert and Lin argued that the characters’ behaviors resembled those of teenagers in general, and viewers therefore should not have seen their “race” at all.

These divergent attributions of responsibility reveal opposing assumptions about the point at which racial difference materializes and disappears: on the body of the actor, in the behavior of the characters, or in the vision of the spectator. Missing, however, is a sense of how these points might align or clash, thus prompting the kind of dispute that arose at Sundance. The terms of the argument moreover elide the conceptions of class and national identity couched within claims about the film’s relationship to race. Although most accounts of the dispute mention only that the audience member deplored its negative depiction of Asian Americans, Daniel Yi reports that he actually criticized the filmmakers for making a movie “so empty and amoral for Asian Americans and for Americans” (emphasis added).34 If Yi’s report is accurate,35 Ebert’s response may have deflected attention away from the film’s depiction of Americans (as well as Asian Americans) and the question of how its representations of “Asian Americans” and “Americans” might be related.

Curiously, the film itself explicitly engages with the issues of race and representation debated at the Sundance screening. The prominent place it gives to these issues belies Ebert and Lin’s insistence that it is not specifically about Asian Americans, even as it cynically predicts the kind of audience response that first provoked Ebert’s defense. In a case of life unwittingly imitating art, both the film and the argument that followed the screening manifest the contradictory demands of racialization, understood as the framing of corporeal traits as markers of innate differences, and assimilation, understood as the adoption of normative behaviors (here, within a particular national context). These dual pressures are crystallized in Better Luck Tomorrow by the characters’ double lives, which parallel—too neatly for coincidence—the stereotypes of the model minority and the yellow peril. The film asks how one body might simultaneously hold the model minority and the yellow peril as identifications—both burdensome and useful—that must be constantly managed in negotiation with others. By splitting Asian Americans between “good” and “bad,” the model minority and the yellow peril create a space of desire as well as a restrictive dichotomy. These figures offer different temptations to the teenagers of Better Luck Tomorrow. Simultaneously seduced and threatened when they encounter images of themselves and others as stereotypes, they move between roles by expanding their repertoire of the mundane.

In its depiction of high school students who alternately embrace and resent their identification as Asian, Better Luck Tomorrow reflects a distinctly contemporary ambivalence about race. This ambivalence is the peculiar offshoot of the major social and institutional changes brought about by the social struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, and the reaction against identity-based politics that followed. Racial identity in the film is not a clear basis for either oppression or resistance, but exerts a more nebulous force. Situated firmly in the middle class and headed for an elite university, Ben, the central character, seems to exemplify the success—or, as some argue, the current obsolescence—of efforts to combat racial inequality. Yet even as Ben initially rejects the idea that race has any bearing on his life, he continuously finds escape either impossible or undesirable. As Ben and his friends shift between reluctant and deliberate enactments of the yellow peril and the model minority, the abject body (figured unambiguously as a corpse in the backyard) warns of the deeper stakes of their performance.

The film begins with a tall gate sliding open, inviting viewers into a clean suburban community lined with identical, pastel-colored homes. An ice cream truck then rolls down the street, chased by a group of excited children. With this belabored first image of American suburbia, Better Luck Tomorrow emphatically sets itself in the United States (more precisely, in Southern California) before focusing the camera’s gaze on two teenagers, Ben and Virgil, as they lounge in a backyard. Virgil asks Ben, “Are you done yet? Early admissions? Ivy Leagues love it. Gets ’em all wet. All that studying finally pays off and you get to leave this hell-hole a year early.” As Ben silently tolerates Virgil’s rambling, an electronic ringing interrupts their leisurely sunbathing. When the two boys realize that the noise is coming from the ground instead of their pockets, they look at each other with alarm and frantically begin to dig into the yard, eventually coming upon a lifeless hand. As Ben contemplates in a voice-over, “You never forget the sight of a dead body,” the film flashes back four months to show the series of events that led to this moment.

The first scenes of Better Luck Tomorrow emphasize that it is telling a distinctly American story, one set after those once excluded from entry have passed through the gates and made themselves at home. As David Palumbo-Liu argues, “The move to the suburb by assimilated ethnics underscores the perpetuation of a particular narrative of ethnic mobility deeply linked to a closing off of space to any who have not passed through a specific process of becoming American.”36 From this perspective, the presence of two Asian American teenagers in an idyllic American suburb seems to represent the end of a journey from outsider to insider, hardship to success. Furthermore, the complete absence of parents, who are mentioned but never shown, distinguishes Better Luck Tomorrow from earlier Asian American films, many of which, as Jun Xing points out, are family dramas.37 Lisa Lowe contends that familial relations in Asian American novels often symbolize a process of swapping an “original” Asian culture for an American one, an argument also applicable to Asian American films.38 With parents and older generations kept out of sight, Better Luck Tomorrow establishes firm spatial and temporal boundaries around its characters, neatly avoiding any suggestion of migration or transnational affiliations.

Under the sun’s glare, however, Ben and Virgil look simultaneously relaxed and uncomfortable. In the spotlight, they are not only the central subjects of the film, but also objects of scrutiny, and the deceptiveness of the innocent ice cream truck that traverses the opening scenes becomes quickly apparent. Virgil’s monologue, despite its focus on college applications, describes early admission in explicitly sexual terms and reveals that he sees college as an opportunity to leave “this hell-hole,” presumably the pristine suburban setting. The ringing of the cell phone further disrupts the prosaic scene, and the appearance of the hand, which recalls the dismembered ear found at the beginning of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), reveals that the pleasant surroundings disguise a grim underside. As the camera fixes on a worm crawling on the corpse, it becomes clear that the seemingly passive American backdrop can suddenly intrude into the narrative and pull the characters from their rest. Although the scene begins as a picture of suburban ease, the unearthing of the dead body, which leads into the flashback that absorbs most of the film, suggests that Better Luck Tomorrow will expose what the teenagers’ presence in this landscape buries and erases.

When the film moves into the past, presumably to explain the corpse, it presents two possible beginnings to the story. Ben selects one beginning himself. Early in the flashback, Ben successfully tries out for the school basketball team, only to have Daric, the editor of the campus newspaper, ask him, “How do you feel about being the token Asian on the team?” Although the question bewilders and angers Ben, Daric subsequently writes an inflammatory story that incites students to protest Ben’s benchwarmer status and eventually leads to his withdrawal from the team. The incident appears to be a humorous interlude and a jab at identity politics without significant consequence, particularly since Ben and Daric become friends. Yet near the end of the film, after Ben and Daric have murdered another student (the one buried in the backyard) and Virgil has attempted suicide, Ben asks Daric why he wrote the story. Daric responds with a confused look, suggesting that he does not understand why the article is relevant in the aftermath of such violent events. Daric’s article, however, is significant for drawing attention to Ben’s racial difference. Claiming that racialization begins with the article would ignore the larger social forces from which ideas of “tokenism” emerge. Daric’s story nevertheless seems to activate Ben’s awareness that his body is racially marked. However firmly he is planted in the film’s overstated depiction of American suburbia, Ben must reckon with the susceptibility of his body to signify “otherness.”

Ben’s unexpected reference to the article after the murder connects it to the dead body, and consequently links the racial awareness that it sparks to the corpse that haunts the film. While Better Luck Tomorrow insists on depicting its characters as quintessentially American, it unsettles the teleology of assimilation by inserting racialization as a lurking, interruptive force. Abrupt jumps in chronology and repeated images of gates opening and closing throughout the film capture these disruptions by undermining a sense of temporal linearity and spatial stability. In contrast to the passage from racial difference and conflict to assimilation conceptualized by Robert E. Park’s “race relations cycle,”39 the film’s more erratic rhythms suggest continual movement between inclusion and exclusion. Lowe argues that narratives of immigrant inclusion are paradoxically “driven by the repetition and return of episodes in which the Asian American, even as a citizen, continues to be located outside the cultural and racial boundaries of the nation.”40 The variable position of Asian Americans, which makes inclusion always tentative, reveals a symbiotic rather than oppositional relationship between racialization and assimilation: Anne Cheng contends, “Racialization in America may be said to operate through the institutional process of producing a dominant, standard, white national ideal, which is sustained by the exclusion-yet-retention of racialized others.”41 In a circular process, the persistence of racial hierarchies, however implicit, encourages racialized minorities to seek assimilation and sets racial limits on its fulfillment, such that the promise of assimilation maintains the very racial hierarchies that it would seem to undermine. This contradictory dynamic exemplifies what Lauren Berlant calls a relation of “cruel optimism,” one that exists “when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.”42

When Ben names Daric’s article as the origin of the violent events that subsequently take place, he assumes that racialization and assimilation are separate processes; by racially marking him, the article disrupts his progress toward a good life. Yet the film coyly undermines this assumption by showing that assimilation is itself deeply racialized, and that notions of racial difference persist through, and not despite, the teleology of assimilation. Whereas Ben traces the corpse back to Daric’s article, the actual beginning of the flashback is a sequence of images of Ben diligently working, studying, doing community service, and applying to college. Quickly displayed photographs of Ben and each of his friends—Daric, Han, Virgil, and Stephanie—then give a glimpse of their backgrounds and interests. While not all of the characters match Ben’s proximity to popular conceptions of the model minority high school student, many of these photographs associate them with typically American experiences: Ben singing in a church choir and wearing a cub scout’s uniform; Daric smiling with President George W. Bush; and Stephanie holding a hunting rifle and wearing a cheerleader’s outfit. Pictures of hapless Virgil and cool Han fill out Better Luck Tomorrow’s breakfast club.

In addition to these photographs and the opening shots of the ice cream truck and suburban homes, the camera lingers early in the film on a fast-food restaurant, a baseball diamond, and high school hallways full of the adolescent types that invariably populate American teen films and television shows. As Cheng points out, “We so often think of stereotypes as about the minority that sometimes we fail to see that the norm is of course itself a stereotype: a stereotype that has been legitimated, a performative expression par excellence.”43 By overloading its introductory scenes with activities and places that collectively accentuate the characters’ Americanness, Better Luck Tomorrow arguably caricatures these expressions of national identity, offering the kind of “hyperbolic citation” of norms famously theorized by Judith Butler in relation to gender performativity. Butler argues that “acts, gestures, enactments, generally construed, are performative in the sense that the essence or identity that they otherwise purport to express are the fabrications manufactured and sustained through corporeal signs and their discursive means.”44 Asserting that behaviors that seem to reflect an identity are what produce and maintain it, she theorizes that gender is not something one displays, but something one does. Butler moreover emphasizes that the citation of norms is compulsory to the extent that it is necessary for the formation of legible subjects, as well as exclusionary in its production of a constitutive “outside” of abject bodies and disavowed identifications.45 The impossibility of perfectly occupying any normative identity and the possibility of repeating conventions inappropriately or excessively, however, allow for a space of potential resignification. Butler posits, “Paradoxically, but also with great promise, the subject who is ‘queered’ into public discourse through homophobic interpellations of various kinds takes up or cites that very term as the discursive basis for an opposition. This kind of citation will emerge as theatrical to the extent that it mimes and renders hyperbolic the discursive convention that it also reverses.”46 Without assuming the subversiveness of such exaggerated and improper performances, Butler proposes that they may hold critical potential.

It is tempting to apply Butler’s analysis to the initial scenes of Better Luck Tomorrow and to argue that its portrayal of prototypical American settings and lifestyles “mimes and renders hyperbolic” conventions of Americanness, the performativity of national identity. The model minority stereotype, however, complicates this argument by insinuating a ready frame through which to see the characters’ behaviors. To the extent that the model minority stereotype “renders hyperbolic” the assimilation of Asian Americans, and thus racializes assimilation itself, it casts supposedly normative behaviors as performances of racial difference. In other words, the stereotype characterizes as remarkable and peculiar the very movement engrained in the national imaginary as the natural course of becoming American.47 While praised for being hard-working and self-reliant, the model minority can never be American, but can only mimic Americanness, performing it badly, partially, or so well that the performance elicits incredulity.

Better Luck Tomorrow asks viewers to attend to Ben’s daily activities by presenting them in a highly exaggerated, repetitive style that lends them an uncanny quality. The flashback begins with Ben at work in a fast-food restaurant, where the employee of the month plaque shows that he has held that honor for several months: shots of these awards in quick succession emphasize the repetitiveness of this achievement. Similarly, when Ben practices free throws at a neighborhood basketball court, abrupt cuts move the film quickly through multiple images of the ball flying toward the basket; these recurrent shots then match the regular series of Xs that he records in a notebook to track his progress.

Yet what is the relationship between the activities depicted in these scenes and the representational modes used to depict them? Is the film attempting to convey the repetitive, excessive quality of Ben’s behaviors, or are its formal manipulations instead generating the impression of excessive repetitions? By introducing each character through a series of photo stills—through images that are explicitly cut, framed, and stacked—Better Luck Tomorrow highlights the selectiveness of its depiction; yet when it shows Ben’s many awards and his diligent basketball practice, it blurs the line between what Ben does and how his activities are represented. Locating strangeness in the execution of these activities renders Ben a figure of robotic dedication, the “weird Asian automaton” eschewed by Chua and implied in characterizations of Asian and Asian American students as adept at rote exercises, but not creative thinking. Locating strangeness in the representational mechanism, by contrast, exposes the dangers (or the redundancy) of defamiliarizing the American mundane through bodies already regarded as imitative, suspicious, and alien. By making it difficult to distinguish between enactment and representational apparatus, the film simultaneously mimics and critiques the naturalization of racialized perception, a process by which the racially marked body comes to seem expressive of—and thus becomes confused with—the mode in which it is seen.

Thus, although Daric’s question about tokenism seems to mark the moment when Ben becomes cognizant of his racial identification, the exaggerated, repetitious quality of the preceding scenes that show Ben’s daily activities slyly evokes popular depictions of the model minority high school student. A 2005 Wall Street Journal article titled “The New White Flight” exemplifies these depictions, even as it concurrently documents their pernicious influence.48 The article reports that white students in Northern California are leaving schools with large numbers of Asian Americans because of the latter’s intense competitiveness and focus on math and science over the liberal arts. According to some of the white and Asian American parents and students interviewed, Asian Americans are not just successful in school, but excessively and inappropriately so. The article concludes with the story of a white student who decides to move to a school with lower test scores where “Friday-night football is a tradition,” in a revealing conflation of a smaller population of Asian American students with the retention of hardy American athletic traditions.49

This article sheds light on why, despite their stylized portrayals, none of Ben’s activities attract much attention within the film until he joins the basketball team, after which Daric’s story and a student’s joke that Ben is the “Chinese Jordan” explicitly frame this activity as peculiar.50 These distinct modes of “defamiliarizing” Ben’s everyday behaviors (loosely, extradiegetic and diegetic) suggest that although the Asian American model minority and the Asian American athlete are both objects of curiosity, the former has been naturalized—body, behavior, and perception aligned in stereotype—while the latter, at least at the time of the film’s release, contradicted accepted distributions of bodies and behaviors. Although Ben would like to be “just” another basketball player, the other students continue to remind him of a disjuncture between his racial identification and his choice of extracurricular activity. Together, the curiosity directed at the model minority as a racial type and the keen attention given to the Asian American basketball player as a racial anomaly regulate racial boundaries by flexibly calibrating standards of “typical” behavior for different groups. Although Ben continues to practice free throws by himself after leaving the basketball team, it is only when basketball becomes a purely personal and often solitary activity with no connection to public spectacle or to college applications (he notes earlier that even if he is a “benchwarmer,” he can include the team as an extracurricular activity) that the film conveys his time in the basketball court more naturalistically. Only then does basketball become a reprieve from his other pursuits, which pull him toward the opposite extremes of Asian American racial formation.

The film reveals early in the flashback that Ben enjoys occasionally deviating from his routines of work and study to run small cons and pranks with Han and Virgil. “I guess it felt good,” Ben explains, “to do things that I couldn’t put on my college application.” He insinuates that these transgressions provide him with a measure of independence, a space outside the voracious college application, which demands and consumes countless academic achievements and extracurricular activities. Soon after Ben leaves the basketball team, Daric invites him to join a lucrative cheat-sheet scam, and while initially reluctant, Ben develops a tentative business partnership and friendship with Daric. Such activities, however, remain largely contained affairs. The significant break occurs when an athlete at a party ridicules Ben as the “Chinese Jordan.” Daric instigates a fight in response and eventually brandishes a gun. As the other student lies helplessly with Daric’s gun aimed at his head, Virgil begins gleefully kicking him and encourages Ben to participate. When the group returns to school the next day, rather than face punishment from school officials, the police, or parents as they had expected, they find that the other students now treat them with fear and respect.

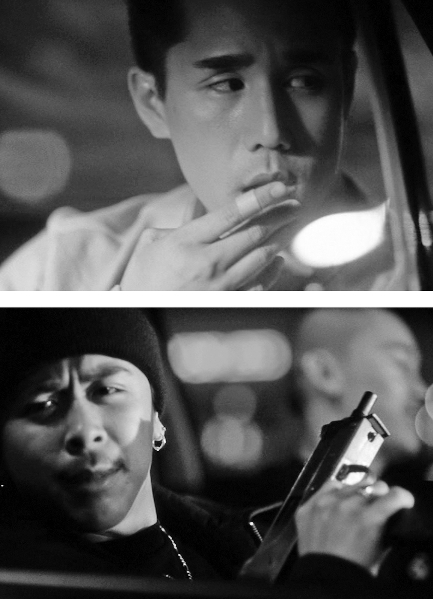

The film therefore presents the fight at the party as a transformative moment for the group: with their new reputation, Ben and his friends become the center of illicit activities at their school. Yet the filmmakers insert a curious encounter immediately following the fight that shadows the double life that they subsequently cultivate. As they drive away from the party, Virgil talks excitedly while Ben, Daric, and Han sit in silence. While Virgil remains oblivious, a group of young men (whose ambiguous racial identifications I address below) drive up next to them and begin yelling and making threatening gestures. One even holds up a gun much more intimidating than Daric’s. As Virgil recalls the fear on the student’s face when Daric wielded his gun (“Did you see the look on that guy’s face? You put the fear of God into him, man. The fear of gods”), the camera focuses on Ben’s nervous visage as he stares at the car next to them (Figures 4.1 and 4.2). Meanwhile, Daric lowers the volume on the music that had been playing in their car. The film never allows us to hear what those in the other car are actually shouting; Virgil’s chattering is the only audible speech during this scene, and he eventually shifts from reveling in the scuffle to panicking at the thought of being punished. As the group waits tensely, the other car finally drives way.

The scene establishes both a parallel and an opposition between the two cars, which seem to mirror each other even as they clearly divide the two sets of occupants. Given that Ben and his friends seem to be middle-class high school students, the appearance of the other car might point to the dangers of conflating the performances of these relatively privileged teenagers with the experiences of those who live in conditions of daily violence and economic hardship, experiences the boys cite but from which they are insulated by the gates of the suburban community that open Better Luck Tomorrow. Yet how do we determine that those in the other car are more real as gangsters than the main characters of the film? Such a reading depends on the assumption that the performances of those in the other car more accurately reflect their everyday conditions within the world of the film. Their masculine displays, however, are no less hyperbolic than those of Ben’s group: they blast music while flashing a gun and looking intensely at the teenagers. The threat they pose seems, within the limited space of the film, less affirmed by evidence of their fearsomeness than by the fear evident in the expressions of Ben, Daric, and Han, whose faces and behaviors reflect back the “authenticity” of the performance. The dynamic between the bodies in the two cars, then, constructs a reality for the other group of young men retroactively, generating a network of relationships between their performance and the experiences and material pressures it might index. Thus, although the scene accentuates the difference between the two cars and casts the film’s central characters’ performance as inadequate, this difference is ultimately as unverifiable as that perceived by Chua in the Juilliard waiting room. The space between the cars constitutes an opening, an invitation to cross, as well as a divide. Similarly, when Virgil’s recollection of the other student’s terrified look converges with Ben’s uneasy expression while staring at the other car, this juxtaposition undermines the triumphant tone of Virgil’s story (reinforcing a sense of difference between the cars) and conjures a moment when they were also able to instill the “fear of gods” in others (suggesting a resemblance between the cars).

Figures 4.1 and 4.2. Ben stares nervously as young men in a car begin yelling and making threatening gestures. Better Luck Tomorrow, directed by Justin Lin. MTV Films, 2003.

This strange moment in Better Luck Tomorrow marks a crossroads in the film. The turn in Virgil’s long speech from excitement to anxiety and his friends’ subdued demeanors as they watch the other car suggest that they accept their performance at the party as a brash and unsustainable act that they already regret. Yet they find at school the next day that their peers now mirror the apprehensive expressions that they transmitted to the other car, realizing them as figures of threat. The lesson that they consequently absorb from the other car is not that they should be wary of trying to emulate the model minority’s others, but that the efficacy of their performance depends on its persuasiveness, on what gets reflected back by their audience. Ben recounts, “We had the run of the place. Rumors about us came and went fast and furious. One had us linked to some Chinese mafia. It was fine with us because it just put more fear into everyone.” Although Daric’s branding of Ben as a token Asian and the teenagers’ reputation as part of a “Chinese mafia” derives from a similar stereotyping of their bodies, Ben willingly accepts the latter for the power that it offers him. Daric’s article indeed gives Ben his initial education on the measurements made on the racialized body. If, despite Ebert’s appeal, Ben is made to represent Asians and Asian Americans, that is, if he cannot elude the racialization of his body, what are his options for performing within its constraints? Newly wise to the ease with which racialized bodies get attached to certain roles and not others, Ben seeks alternate experiences by assuming the role of the model minority’s other, in this case, the yellow peril gangster.

In criticizing the film’s preoccupation with the teenagers’ subsequent spiral into criminal behavior, the audience member at Sundance registers the negative impact it may have on perceptions of Asian Americans, but fails to recognize the appeal that such depictions may hold for Asian American men who find themselves frequently portrayed as weak, effeminate, and asexual. When the preface to the influential Asian American anthology Aiiieeeee! (1974) made its rallying figure the “wounded, sad, angry” yellow man,51 it tied Asian American cultural nationalism to the project of recuperating Asian American manhood. The continuing influence of this project is evident in Asian American cinema, about which Celine Parreñas Shimizu observes, “Contemporary Asian American male filmmakers and actors see the Asian American male body as a site of racial wounding, gender grief, and sexual problems in ways haunted by the framework of falling short of the norm.”52 Shimizu suggests, however, that films like Better Luck Tomorrow also make it possible to explore alternate forms of manhood through their representation of “the plenitude of Asian American male actualities and desires.”53 The film indeed presents a diverse set of Asian American men, from clownish Virgil to quietly assured Han. Yet while offering several models of manhood, Better Luck Tomorrow also highlights the continuing allure of hypermasculine roles for those who are racialized—and gendered—as less than men. The antics of Virgil and Daric in particular express a desire to be other than the emasculated Asian man, other than the model minority—even by adopting an equally stereotypical role. As Josephine Lee points out, “Stereotypes of Asian Americans are no longer simply the seductive images of the Orient rendered for consumption by white audiences. Instead, they have become woven into the complex fantasies Asian Americans have about identity, community, and gender.”54

Embracing the label of the “Chinese mafia” for the fear it incites and charging the role with hypermasculine displays, the characters’ performance of a sexualized yellow peril is symptomatic of the temptation, against which Butler warns, to regard the enactment of social identities as simply a matter of voluntary role-playing. As the friends repeatedly embody the Asian gangster before those who assume the “reality” of their performance, the lines between “self” and “role” prove difficult to sustain. Becoming increasingly invested in his performance, Ben recounts, “I soon learned along with image came maintenance. I needed something to expand my days. It’s literally a full-time job just to make people believe who you’re supposed to be.” While Ben still insists on making a distinction between who he is “supposed to be” and the person he actually is, when he wakes up one morning with a bloody nose from taking too many drugs, we are reminded of his remark while memorizing words for the SAT test: “They say if you repeat something enough times, it becomes a part of you.” Following this advice, Ben repeats SAT words and their definitions at regular intervals in the film, and the word that he recites reflects some aspect of his life or behavior at that moment. The first word, “punctilious,” and its definition are superimposed on a shot of Ben as he lies in bed while memorizing the word; the word is therefore literally impressed on his body as it is being impressed on his mind (Figure 4.3). As he then moves through “temerity,” “quixotic,” “catharsis,” and “inextricable,” the alignment of these words with the action of the film insinuates that the words themselves are shaping him, are indeed becoming a part of him. The designation of “Chinese mafia” has a similar effect on Ben: thus interpellated by the other high school students, Ben finds the words infiltrating his body. Repeatedly enacting the role of the Asian gangster, he is unable to maintain his sense of certainty in a “self” separate from the character he plays. Although Ben would like to believe that his act as a member of a “Chinese mafia” is “not him,” his embodiment of the stereotype also makes it “not not him” (the double negativity that Richard Schechner ascribes to performance), and he must grapple with the uncertain boundary between the two. Through their daily repetition, the very performances that Ben initially understands to be artificial infiltrate the mundane, forcing him to “expand [his] days” to accommodate their demands on his body and routines.

Yet even this taxing blurring of “self” and “other” proves insufficient to secure with consistency the audience’s belief in his various roles. Enjoying their new wealth and reputation as the “Chinese mafia,” the teenagers hire a stripper for one of their parties. At the end of the night, she asks, “So what are you guys?” Although her question initially suggests that she sees them as mysterious Asian gangsters, when Virgil tells her that they are a club, she responds, “Oh, like a math club, or something?” The expression of displeasure on Daric’s face indicates that she misinterpreted their performance. If Ben and his friends want to play racial stereotypes, they must also accept the highly contextual and audience-dependent nature of all performances. While they might try to change what their racialized bodies signify, they can never fully dictate the effects of their performance. Whether the characters demonstrate their assimilation by adopting behaviors that promise the American dream or attempt to take advantage of racial fears, their conferrals and struggles with multiple audiences delimit what they ultimately perform, and what their performances ultimately do.

Figure 4.3. Ben memorizes words for his SAT exam. Better Luck Tomorrow, directed by Justin Lin. MTV Films, 2003.

Furthermore, whether the characters in Better Luck Tomorrow see the embodiment of stereotypes as a burden or an opportunity, their performances take shape and significance not just in their encounters with other bodies, but also against other bodies in a complexly multiracial and gendered landscape. The backdrop of American suburbia is itself a racialized space, and the emphatic images of a middle-class neighborhood and high school that open the film make the setting particularly salient. Implicitly, it is whiteness against which the teenagers’ achievements are assessed, while activities that fall outside its bounds tend to evoke other racial stereotypes. In his comparative study of the works of Frank Chin and Ralph Ellison, Daniel Y. Kim draws attention to a scene in Chin’s essay “Confessions of the Chinatown Cowboy,” in which Chin bitterly recalls a police officer berating his black and Latino friends for not being more like the (well-behaved) Chinese. Reading this moment, Kim argues, “In the multiracial culture [Chin] describes, in which none of the acknowledged models of racialized masculinity are yellow, the only way for an Asian American male to pass as masculine is to engage in a kind of interracial performative mimesis. Yellow manhood is presented here as a signifying practice—as something one communicates through the repetition of stylized bodily gestures that belong, properly speaking, to men of other races.”55 Kim contends that in Chin’s writings, popular conceptions of Asian American masculinity as lacking become connected to a “kind of defective or failed mimesis . . . a certain impoverished modality of assimilation.”56 The apparent unavailability or illegibility of “yellow manhood” means that imitating the “stylized bodily gestures” of other men comes to serve as limit and possibility. The frustrations expressed by Chin find an echo in Better Luck Tomorrow as efforts by characters to assert their manhood often misfire, returned as unconvincing or as derivative. The epithet “Chinese Jordan,” used to taunt Ben, and Virgil’s cringe-worthy citations of blackness,57 for example, revive stereotypes of other racialized bodies while casting Ben and Virgil’s behaviors as imitations, whether through the voice of another character or through the excesses of the performance itself.

Racial identification is a necessarily comparative exercise, one that involves making simultaneous assessments of the fit between bodies and behaviors across multiple racialized groups. The film dramatizes this process in the moments described above, particularly in skeptical responses to Ben’s membership in the basketball team. Yet the process also becomes evident in responses to the film, as Manohla Dargis’s review for the Los Angeles Times demonstrates. Referring to the fateful scene when the two cars drive next to each other, Dargis describes, “Without warning, the beats floating off the car stereo are drowned out by a louder, more insistent rhythm as a car carrying four Latino gangbangers slides next to the Mustang.”58 Reading this review, I was struck by our discrepant perceptions of the so-called gangbangers’ “race,” for I had presumed that the actors were Asian American. This scene would then establish a contrast between the double lives of Ben and his friends, and the doubles who embody the role of Asian gangsters more persuasively, a meeting that stages the paradox of Asian American racial formation as an unraveling dichotomy, spinning between opposition and equivalence. On the one hand, Dargis’s review is a useful reminder that the model minority’s “other” comprises not just the yellow peril (as an opposing stereotype) or struggling communities within Asian America (as a counterexample), but also the minority groups against which Asian Americans are set as the “model.” On the other hand, the review also raises the uncomfortable question of how she came to see the actors as Latino. The review does not necessarily affirm the stereotype of “Latino gangbangers” (in other words, it does not assume the validity of the representation), but it nevertheless replicates its alignment of bodies and behaviors, while implicitly casting such performances by Asian American men as a “defective mimesis,” the enactment of bodily gestures that “belong . . . to men of other races.”59 Stereotypes are not simply attached to bodies already categorized by race, but impact how such identifications are made.

Discrepancies in racial identification evince the fundamental untenability of such classifications, yet they also illustrate that regardless of “accuracy” (already a dubious criterion for assessing questionable distinctions), such identifications are always meaningful and efficacious. For those who are racially marked, the credibility of a performance, determined in often swift and half-articulated assessments of the relationship between how one looks and how one behaves, has significant consequences that extend beyond casting questions to questions of who gets to live and how. Despite changing conceptions of race that have weakened essentialist claims, racialized measurements of the fit between body and behavior continue to shape how people and institutions distinguish between the normative and the deviant, the credible and the implausible. These measurements influence everyday social relationships and play an important if often implicit part in debates about domestic and foreign policy and the distribution of resources. Both the model minority and the yellow peril stereotypes, for example, imply that certain groups are more or less deserving of economic aid and success. While policymakers have deployed the model minority stereotype to argue against affirmative action and welfare programs, the yellow peril found renewed salience in the 1980s amid fears that Japan posed an economic threat to the United States. The murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese American man, by two automobile workers in Detroit allegedly resentful of the Japanese car industry, is but one infamous example of how racialized perceptions take on a reality with significant material consequences, in both the corporeal and the economic sense.60

The Better Luck Tomorrow teenagers, however, embrace the stereotypes of the model minority and the yellow peril for the privileges they afford: monetary gains from their various ventures, the trust of adults who assume their good behavior, and the respect of students who fear them. In their efforts to play the “Chinese mafia” while continuing their academic and extracurricular pursuits, they dwell in the space between their car and the car of their more intimidating counterparts. They seek to manage this ambiguous space—which, as I argued above, is both a divide and an opening, a threat and a temptation—by becoming similar enough to their doubles to benefit from the proximity, but not so similar that they erase the difference between them. Hinting at the impossibility of this task, the film continuously draws attention to the various factors that affect the teenagers’ attempts to make these partial crossings: the fear in the eyes of other students facilitates their passage, but the stripper’s cheerful query about their math club obstructs it; the demands of maintaining their grades and winning Academic Decathlon competitions keep them close to a certain kind of life, while the expansion of days through drug use pulls Ben too far into another kind of life.

Better Luck Tomorrow’s version (or reversal) of the coming-of-age narrative tracks Ben’s unraveling sense of self as he struggles to retain control over his numerous performances—those required to meet standards for school and college admissions, as well as those he adopts to play a member of the “Chinese mafia.” Although he initially clings to his activities as a responsible high school student as his real life and even attempts at one point to give up the group’s illegal schemes, his rival for Stephanie’s affection—her boyfriend Steve—undermines his remaining sense of agency. Claiming that Ben is working toward submission rather than achievement, Steve entangles him in a minor plot to reject the system of incentives that encourage “model” behavior. In the violent struggle that then transpires, Ben’s most vehement assertion of will materializes the very constraints that Steve had intended to challenge with his help.

A rich private school student, Steve is an enigmatic figure who appears largely untouched by the anxieties and desires of the other teenagers. When Ben and his friends approach Steve’s home, they encounter a gate that prevents them from entering. Steve seems to have passed through a second “gate” dividing the model minority middle class from the wealth and privileges of the elite classes. Despite his perfect grades and certain future at an Ivy League university, Steve emphasizes connections, rather than diligence, in achieving success. He offers to get Ben an internship, saying, “I know some people, I’ll give them a call.” Steve is not the stereotypically hard-working model minority; instead, he seems to have access to the “old boys’ network” associated with white privilege.

Steve moreover explicitly dissociates himself from other Asian Americans. Arriving at a party inebriated, he jokes, “So this is where the Asians hang out.” When Daric sarcastically affirms, “Yup, the library was closed,” Steve responds, “Hey, you’re a funny guy. For an Oriental.” By insisting on his lack of familiarity with the routines of other Asian Americans, Steve emphasizes his difference. Daric’s reply registers the importance Steve places on not engaging in the “typical” behaviors of Asian Americans by, for example, hanging out in the library. Yet the fragility of the distinction that Steve tries to enforce between himself and the other characters nevertheless becomes clear when Virgil sees Steve in his characteristic long, dark coat and jeers, “I’m Chow Yun-Fat,” comparing Steve to a well-known Hong Kong action star. By taking on Steve’s voice, Virgil implicates himself in the name-calling he directs at Steve, highlighting their mutual interpellation as, and attempted disaffiliation from, “Orientals.” Attaching his insult to the exceptional rather than the ordinary, Virgil’s remark suggests that even if Steve could distance himself from everyday activities associated with Asian Americans, he would not be able to extricate himself completely from the spectacle of racial difference.

Distinguished from Ben’s group by his easy privilege, yet sharing an uneasy racial association, Steve offers a seductive model of what they might attain. When he subsequently rejects the privilege that inspires the other teenagers’ envy and resentment, he triggers a violent response that reinforces the boundaries of acceptable behavior. Success, Steve warns Ben, demands compliance with existing social structures while giving the illusion of agency. At a batting cage, Steve asks, “You happy, Ben?” to which Ben replies, “I don’t know.” Steve responds, “Fuck. That’s the most truthful thing I’ve ever heard. At least you have a choice. I have everything—loving parents, top grades, Ivy League scholarships, of course, Stephanie. . . . I’m so fucking happy I can’t stop it.” Slamming baseballs throughout his monologue, Steve continues, “It’s a never-ending cycle. When you got everything, you want what’s left. You can’t settle for being happy. That’s a fucking trap. You got to take life into your own hands, do whatever it takes to break the cycle.” The image of Steve partaking in a traditional American pastime as he gives his monologue evokes the reproduction of national values and customs, with Steve embodying the attainment of the American dream. The scene, however, emphasizes Steve’s sense of confinement rather than accomplishment, affirming that his present happiness is one of passive acceptance, a “trap” that brings success without agency. The batting cage, enclosing Steve on three sides, visually re-creates his feelings of imprisonment, while his repetitive acts of hitting the ball suggest the “never-ending cycle” of acculturation and accumulation. Cinematic techniques further stress a sense of endless, inescapable repetition: the scene switches strangely from day to night, and abrupt cuts juxtapose in an unrelenting series multiple meetings of bat and ball and Steve’s persistent question of “What?” when Ben begins to laugh.

In order to “break the cycle” and “take life into [his] own hands,” Steve proposes giving his parents a “wake-up call” by robbing them. The significance of this puzzling scheme (how exactly would this liberate Steve?) is legible only within the particular symbolic associations established in the film. Steve’s idea of breaking the cycle perpetuates the wider disavowal of parental figures in Better Luck Tomorrow, but it also reflects his resistance to a broader societal parenting. If, as Steve insists in his rant to Ben, the comforts of abiding by established conceptions of achievement deplete real agency, asserting control requires a complete rejection of the privileges they afford. While this scheme exposes Steve’s avaricious impulse to possess even lack if that is what remains after having everything else, its aborted execution reveals the other characters’ collective investment in safeguarding the possibility of being as “happy” as Steve. Steve’s plot to see what might happen by breaking the cycle not only fails, but it also ends with his death when those whom he solicits as accomplices—Ben, Daric, Virgil, and Han—turn against him and decide to give him, rather than his parents, a “wake-up call.”

The scenes that depict their assault on Steve repeatedly disrupt the viewer’s expectations by switching between styles. Thus disorienting the audience, the film replicates the confusion between real and fake, self and role, experienced by Ben and his friends in their double life, and insinuates that this confusion reaches a crisis point with Steve’s murder. As Steve enters a dimly lit garage, Daric, Virgil, and Han surround him with menacing looks. Daric even coolly smokes a cigarette. The spotlight of a garage lamp adds an exaggerated quality to the encounter, imbuing their behaviors with an affected air and suggesting that the teenagers created an overtly theatrical scene. Once they begin beating Steve, however, close-ups and erratic lighting replace this distanced view with a sense of immediate, palpable chaos, which escalates in the subsequent struggle for a gun. The gun goes off, but the film then cuts to an image of Ben, Virgil, Han, and Daric in a car heading to a New Year’s Eve party. The sudden break leaves the viewer in a state of suspense but insinuates that Steve has been shot.

The film eventually returns to the scene in the garage to show what transpired: Ben, who had been acting as a lookout, rushes in upon hearing the gun fire and finds that no one has been hit by the bullet. The filmmakers thus manipulate the theatrical convention of the gun that appears in an early act and goes off before the play’s end, encouraging then undermining the viewer’s assumption that someone will be shot. Instead, Ben suddenly begins to beat Steve with a baseball bat, spraying blood across Han’s face. The close-ups of the expressions of terror and disbelief on Han, Virgil, and Daric capture their visceral reactions to the beating, and invite the audience to share their repulsion. The film then shifts from graphic violence to discordant comedy when the owner of the garage, Jesus, enters and exclaims, “What the fuck? We didn’t agree to this. This is going to cost you extra.” The wider shot of the dramatic solo lighting that accompanies Jesus’s response further lends the moment a farcical quality. When Steve’s body begins to shake, however, Daric completes the murder by stuffing his mouth with a gasoline-soaked cloth while Virgil holds his head. Close-ups again directly involve the audience in the unpleasant physicality of Steve’s murder. Moving between a visceral, graphic style and a more distanced view with comedic shades, the film encourages continual adjustments in audience expectation and perspective without destroying our faith in its narrative realism: the characters must clean up the blood, get rid of the body, and contend with questions once people begin to notice the victim’s absence. Collectively, these scenes induce viewers to experience the destabilizing interface between styles in shifts that are registered by the body as it laughs or turns away. If the real effects of illusory roles are what drew Ben to his double life, the discomfiting realness of these scenes and the momentary relief offered by the comical interludes simulate an impossible desire to turn back the doubling, to assume, as before, a neat alignment of identity and identification, and a clear boundary between voluntary and involuntary enactments.

A shadow of the Vincent Chin murder crosses the film during this climatic scene: Ben beats Steve with a baseball bat, the very object used to kill Chin, as well as one of the weapons used to beat Stuart Tay. Despite the very different circumstances surrounding the murders of Chin and Tay, they were national scandals in part because they unsettled the notion that Asian Americans were on the right track, that they constituted a chosen minority immune to racism and untouched by the violence that troubled other racialized communities. That a baseball bat was used in these attacks connects these incidents, with lamentable poignancy, to a symbol of national belonging. The baseball bat moreover directly links Steve’s death to his speech at the batting cage. Repeatedly pummeling Steve as Steve had pummeled baseballs, Ben offers him the absolute abjection of “what’s left”: in becoming the buried, the invisible, and the shattered, Steve embodies not a break in the cycles he deplores, but their constitutive remains. Ben indeed enacts the unspoken demands of total assimilation directly onto Steve’s body, fulfilling the process that he had wished to disrupt. Josephine Lee muses, “If the Asianness of the body is read as a nonpermeable boundary, passage of the Asian body through the boundaries of racial categorization requires radical violence.”61 It is exactly through “radical violence” that Ben offers Steve a final transcendence of his racialized body. By then burying Steve, he incorporates him directly into the land itself.

The execution of the imperative to assimilate oneself invisibly into the American landscape by those similarly racialized points to the difficulty of “breaking the cycle” when it continues to promise “better luck tomorrow.” This promise still calls to Ben’s group, as the friends disarm whatever threat Steve may have posed, then avoid, each in his own way, the consequences of the murder. Yet as the ringing of Steve’s cell phone at the beginning of the film reminds them, they will have to continue to reckon with the bodies that refuse a neat suburban burial. Returning near its conclusion to the scene of Virgil and Ben sunbathing, the film seems to accept, through its circular structure, the persistence of the cycles so frustrating to Steve. Importantly, however, it reimagines a tale of progress and triumph as one of burials and hauntings. Although the film initially presents Ben as a paragon of the model minority stereotype, it resists the embrace of what Palumbo-Liu terms “model minority discourse”:

Model minority discourse provides a particularly potent site of subject construction and ideological containment because it achieves its force from the fact that it appears, by dint of mobilizing “ethnic dilemmas,” to be contestatory. Yet the sublation of ideological contradiction within the recuperative operations of individual “healing” vindicates the dominant ideology while rewarding the subject with a particular form of individual well-being freed from both the constraints of collectivity (that is, “I am no longer ‘labeled as Asian American,’ I am an individual”) and its obligations (“I am myself first, and my ‘Asian Americanness’ only partially coincides with that Self, and I can access it at will”).62

According to Palumbo-Liu, the “model minority discourse” prevalent in Asian American literature replicates the ideology it seems to critique by privileging individual achievement over collective responsibilities. This discourse charts a movement from “ethnic dilemma” to “individual ‘healing,’” a trajectory that Better Luck Tomorrow overturns. The image of Virgil, lying with bandages around his head in a hospital bed after attempting suicide, makes clear that rather than moving toward progressive “healing,” the film receives its momentum from the resurfacing of violence. Insisting on the constant intrusion of the abject body into axiomatic tales of assimilation, the film gestures toward the ghosts hidden beneath their well-groomed settings.