Booker T. Jones stood outside the second-floor nightclub and listened to the music. The Club Handy was perhaps the most storied of all the Beale Street joints, the one from which B.B. King was launched, the one where Bobby “Blue” Bland cut his teeth. This club never closed, attracting all the musicians after their own gigs to jam, to “cut heads”—play unfettered and for themselves, without the restraints of pleasing an audience. Booker, who would soon become a pillar for the foundation of Stax Records, was only in high school, but he already knew the insides of many clubs—mostly from the bandstand’s perspective, a high schooler substituting for the regular player who’d taken a night’s society gig or gone on the road with some of the marquee talent that regularly passed through Memphis.

“These bandleaders had to come to my house,” Booker explains about his teenage years, “persuade my mom and dad that they were okay and to let me go with them. Most of the time I was playing baritone sax or piano, but I did have that Silvertone guitar and a little amp. We’d be in these cow pasture joints playing up-tempo blues, and when it gets a little too late and a little too loud and the sheriff is in there and everybody’s dancing and it’s hot and it’s grinding and the guitar gets turned up and it starts to crunch—I could make that guitar do that. And I’d make five or six bucks a night with people like [local bandleaders] Robert Tally and Johnny London and Tuff Green.”

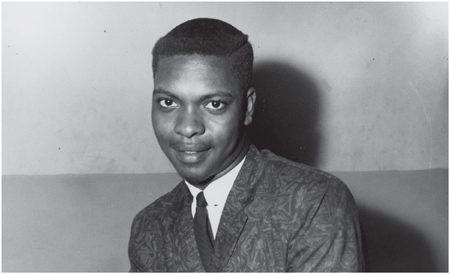

A young Booker T. Jones.

Booker took the nightclub gigs as they came, and the lessons that came with them. Dexterous on several instruments, Booker often subbed on bass with Willie Mitchell’s popular band, and with one led by Al Jackson Sr. Al’s son, Al Jackson Jr., soon to be Booker’s bandmate and a driving force at Stax, became a strong—maybe strong-armed—influence. “I never worked with anyone who thought keeping time was so important,” says Booker of Al Jr. “Al, if I would rush or slow down, he would yell and curse at me—onstage, in front of people. He would hit you over the head with the drumstick if one eighth note or a sixteenth note was off. I mean, he was up and cussing. Al Jackson’s place onstage was behind me and the important thing for me was to keep on time so I didn’t get hit, so he didn’t throw anything or yell at me. That’s pretty good incentive for a fourteen-year-old playing with a borrowed bass.”

Booker had been inside Curry’s Club Tropicana, the Flamingo Room across Beale Street (where his future bandmates Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn saw his reflection in the mirror from the stairwell), the Plantation Inn in West Memphis. He’d played for white rednecks in Millington and for African-American society in South Memphis. But the Club Handy remained a mystery. Where the other clubs hired larger groups like Willie Mitchell’s band, Al Jackson Sr.’s band, the Newborn Family band, Tuff Green’s Rocketeers, Gene “Bowlegs” Miller’s Orchestra, or Ben Branch, Club Handy had a secret weapon: Blind Oscar. Oscar Armstrong played the Hammond organ, and he made the instrument into an orchestra. He had only a drummer and sometimes another instrument behind him, but that was all he needed. “Club Handy would chase us away,” Booker laughs. “‘You boys go on, get away from here.’ They didn’t need us kids to substitute. Oscar could fill that room with music and make it pulsate with the Hammond organ.”

Booker, when he first heard the organ, couldn’t identify it. “I heard the Hammond sound coming out of a Pentecostal church and coming out of Club Handy on Beale Street. Blind Oscar was playing bass on it, and I heard it from Jack McDuff records. But I wasn’t sure what the instrument actually was.” Pentecostal churches, also called sanctified churches or holy rollers, often featured a full band that would help the pastor whip the congregation to a spiritual frenzy. Booker had been warned not to go inside those churches, and he was chased away from Club Handy, so he experienced the intense power of the Hammond organ without being sure exactly what was creating it.

(He finally saw a Hammond organ when he asked his piano teacher what was always kept covered across the room. “I thought it was a china cabinet,” he remembers. His teacher demonstrated the instrument but admonished him not to become entranced by it as he could not afford the lessons he’d need. Soon, Booker was throwing a paper route after school to pay for those lessons, folding the newspapers outside Phineas Newborn’s house, so he could hear the great jazz pianist practice.)

By the late 1950s, going from a Memphis club to the national stage was an established career path. Several decades earlier, a band teacher at Manassas High School in North Memphis named Jimmie Lunceford had taken his students to New York, where he quickly earned the house gig at Harlem’s Cotton Club, from which both Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway had recently broken out. Lunceford’s Orchestra was famed through the 1930s. B.B. King had leapfrogged from a Beale Street talent show to headlining the Club Handy to becoming a national star by 1951. Rufus Thomas had put Sun Records on the map in 1953, and Sun soon launched Junior Parker (Bobby Bland was his valet), Rosco Gordon, Howlin’ Wolf, and then Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Carl Perkins. Bobby “Blue” Bland became his own star. Johnny Ace and Johnny Burnette too. In the jazz world, Phineas Newborn went from local clubs to prestigious New York recording artist in 1956.

While the pay for a musician in southern cities was not as high as for a doctor or lawyer, the job had as much respect. “If the Dixie Hummingbirds came through town, or Pops Staples and the Staple Singers, or Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers came through, they were ambassadors of hope,” says Rev. Jesse Jackson, a future Stax artist who was raised in the rural South. “These were bona fide stars. They belonged to us.” Musicians were pollinators, traveling with the wind of applause beneath their wings, serving not the practical matters of an MD or jurist but rather the essential spiritual side, serving the soul. “So much of our survival capacity came through music and imagination,” Rev. Jackson continues. “People living in the worst of conditions, picking cotton or tobacco, or waiting tables, against all odds—music creates for us a great sense of imagination.”

![]()

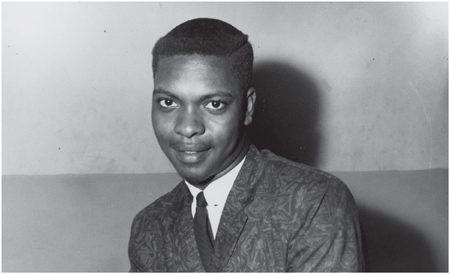

Standing in front of the Capitol Theater, Jim Stewart was approached by a neighborhood boy, African-American, less than ten years old. A white man in the neighborhood was not unusual—if by 1960 the area was weighted more toward blacks, it was still plenty mixed. But no one had poked around the shuttered theater in a long time, and the lad—William C. Brown—had been dreaming of that stage inside nearly all his life. “Jim Stewart was standing outside looking at the building and I was a little kid. So I asked him, ‘What are you getting ready to do?’ He said, ‘It’s going to be a recording studio.’ And I said, ‘I sing.’ Just like that. He started laughing. So when he opened the door, I ran under his arm, right into Stax.” He would soon work for Estelle in the record store, then sing for Stax with the Mad Lads and learn there to engineer recordings.

The neighborhood movie theater where Stax would make its home. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

Brown set the model for getting in the door—walk right in, sit right down, baby let your mind roll on—though it wasn’t quite Stax yet. The company was still called Satellite. Nor was it yet a recording studio. “I had already mortgaged my house, and then to get the operating capital, I had to refinance it,” says Estelle. “I’m one of these that likes to take a chance.” Money in hand, they began transforming the building. “The theater was too big,” Estelle continues. “So we put a partition in. Up on the stage where the screen usually was, that made a good control room, set above the theater floor.” They built a wall with a large window so Jim could see the performers. The slanted floor helped deaden the sound, keeping it controllable.

The kids in Packy’s band, when not in high school classes, helped with the renovation. It would be their rehearsal space when sessions weren’t going on. “It was a very big room,” says Steve Cropper, estimating the studio as two thirds of the theater’s original size; the Capitol had been a neighborhood theater, not a movie palace, but it seated several hundred. “We had to take the seats out and a lot of the bolts wouldn’t come out of the concrete. Packy Axton and I would spend hours with a hammer trying to break these things off so we could lay down carpet.”

“We did the acoustic stuff ourselves,” says Estelle. “We were always do-it-yourself. We put down carpets, we zigzagged acoustic tile down the walls. I had made some drapes for the studio in Brunswick, and we hung those all the way from the ceiling. That stayed there a long time because it was too hard to get down.”

“Jim Stewart and I built these sound panels out of pegboard and burlap,” says Steve. “And we put windows in them, so we could see each other—separate the sounds but have eye contact.”

Inside the control room was the original Altec Voice of the Theater speaker, eight feet tall and five feet wide. It had filled the building with the sound of James Cagney’s bullets and Lash LaRue’s snapping whip, and since the studio only needed to hear it in the control room, they could keep the volume low and get very clear playback. The original echo chamber was the men’s bathroom, tiled from the theater days.

The theater was one entrance in a strip of several adjoining businesses. Immediately to the east, sharing a wall, was the Capitol Barber Shop. Beyond that, a shoeshine stand, then a beauty shop, and on the corner a small grocery store and produce stand, complete with a soda fountain serving kids cherry Cokes after school. West from the theater was a TV and small-appliance-repair service, and then a beer joint that had a variety of names (and commonly known, later, as Slim Jenkins’ Joint, though it was never incorporated as that). As the Stax musicians matured, their foot traffic shifted to the west, from the soda fountain to where people took their blues home in a brown paper bag.

That commercial strip was a complete universe in which the kids could orbit. “One end was a food store, and the other way was May’s Grill,” says future Mar-Key Don Nix. “May was an alcoholic lady, white, and she lived in the place. She’d just pass out at night, wake up in the morning, and take off again. Carl Cunningham, who became the Bar-Kays’ drummer at Stax, was the shoeshine boy at the barbershop. Everybody hung out together and got along. And that was the neighborhood. We’d rehearse all day sometimes, go down to May’s Grill and eat lunch. We’d go to the food store and get sliced baloney and crackers. It was like a job almost, though you didn’t get any money for it. But we were learning something.”

The theater’s entrance was midblock. The ticket booth was still out front, and just inside was the lobby, with the concession stand forming a triangular area that guided you through the curtain and into the theater. Estelle Axton saw the concessions space and saw opportunity—a home for her record shop. “I had been selling records all along,” she says. “Now I’m trying to build some stock. This was a largely black neighborhood so I had to get into the rhythm and blues records, and I’m still buying the other kind too because I’m still working at the bank.” No one gave real consideration to the advantages that would develop—no one conceived what would develop: The store would be a way to gauge what shoppers were buying, would provide immediate customer response to new and developing songs, and would yield a working library so writers and musicians could keep current. The initial purpose was plain and simple: cash flow to help pay the rent.

![]()

The studio’s first real boost came from the postman. He heard about the new place in the neighborhood and spread the news. That he was retired and that the studio wasn’t on his old route—well, this is a story filled with such improbabilities. The postman’s name was Robert Tally, and he was also a keyboard player and bandleader.

Rufus Thomas, left, at the textile mill, watching the vats, making up songs.

“A fella by the name of Robert Tally came by my house and told us that there’s a new recording studio over there at the corner of McLemore and College,” says Rufus Thomas, whose work at Stax would soon make him known as the Funkiest Man Alive but whose superlative then might have been Busiest, as he was working several jobs to make ends meet (despite his local and national fame as an entertainer). He worked full-time at a textile mill, with half an hour to get from there to his afternoon shift on radio. But even on the job, music was on his mind. “I’m watching the cloths fill up in these big old vats,” he says, “and I’m bobbing my head up and down as I watch them, trying to make up songs.” In addition to his work at Sun Records, he’d recorded for Meteor and was active in several other studios around town. “Tally said, ‘I think you oughta go over there.’”

Musicians had been crossing proscribed thresholds in the city for years. B.B. King had gotten his radio show on WDIA by walking through the front door on a rainy day and asking for an audition. Howlin’ Wolf walked into Sun, having heard that the white man Sam Phillips would give you a fair shake. The door Elvis walked through was metaphorical, but his success grew from his knowledge of music on the other side.

Tally had heard about the studio from a mortician in the neighborhood with whom he wrote songs. They’d gone there and cut some demos, been hospitably treated. “They had this Ampex 350 recorder,” says Tally, impressed by the gear purchased with funds from Estelle’s mortgage. “So I told Rufus Thomas, ‘Hey, man, let’s go over there and do some demos on McLemore.’ And that’s how we got hooked up.”

Uninvited, Rufus and his seventeen-year-old daughter Carla drove the mile and a half from their home. “We came right off the street,” says Rufus, “went right in.” In the lobby, they’d have been greeted by Estelle’s Satellite Record Shop: boxes of records spread across the candy counter, and by Estelle herself. She was a radio hound, and would have known Rufus by voice if not by sight; when Jim came forward from the back, he recognized Rufus from his rounds promoting the Veltones. Rufus, however, reveals that he remained suspicious. “At that time, really, I thought nothing about white folks,” he says, as frank as he is funky. “Nothing at all. When I was young, I had some rough experiences—wrong experiences, bad experiences—with white folk. I’m thinking that all white folks are the same. But I know I had to work, and the white folks had the jobs so I did what I had to do. It took me some time to get these things outta my system, and my system was pretty tight.”

Rufus’s simple act of entering on his own terms was actually no simple act at all. As James Baldwin wrote: “[W]hen the black man, whose destiny and identity has always been controlled by others, decides and states that he will reject the identity imposed on him, and control his own destiny, he is talking revolution.”

A revolt of that very nature was fomenting in public on the streets of Memphis. The fear of arrest, and the certain brutality in jail, had quelled activism for generations. But after serving the country in World War II and the Korean War, the black community had a new sense of entitlement. At the start of February 1960 in Greensboro, North Carolina, a sit-in of four students at a white lunch counter grew to three hundred protestors in less than a week; shortly thereafter, Memphis students began a series of similar direct actions, forcibly integrating lunch counters, public libraries, and the art museum. Ministers joined, urging African-Americans to make their economic contributions felt by boycotting downtown businesses on Mondays and Thursdays. Even the most devalued were rumbling. The sanitation department employees worked the worst job in the worst conditions for the worst pay. Many of the department’s full-time employees were eligible for welfare, and many had been there for decades because they knew that, lacking education, lacking training and skills, hauling garbage was as far as they’d go in Memphis jobs. (The head of the Department of Public Works in the latter 1950s, Henry Loeb, had taken to hiring black men with arrest records, knowing they’d have fewer options and thus would be easily victimized.) So the headline on February 6, 1960, stating SANITATION MEN WANT MORE PAY became a call to action; if the garbagemen were standing up for themselves, then many of the city’s African-Americans who’d been afraid to publicly demonstrate had to take stock.

When organizers in 1960 began to unionize the sanitation workers, the city’s new mayor, that same Henry Loeb, responded that he would dissolve the department and hire private contractors before he’d recognize a union—despite the city’s recognition of unions for white-skinned white-collar workers, including those in the sanitation department. Six weeks later, the black public’s anger had increased: NEGROES AT FEVER PITCH. An interracial citizens’ council was formed, and desegregation of public facilities began in earnest, though slowly. The progress at the sanitation department was negligible.

Rufus meeting Jim on McLemore was taking place five years after the nearby Emmett Till murder; three years after the Little Rock Nine defied the city and upheld the nation’s law, integrating their Central High School. It was four years before the federal government passed the Civil Rights Act forbidding hotels, restaurants, gas stations, theaters, and the like to segregate or discriminate “on the ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.” It was five years before the Voting Rights Act, which was passed to buttress the Fifteenth Amendment, created ninety-five years earlier.

The entertainment culture, music particularly, moved at a faster pace than social changes. The year prior to Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, in Memphis a white kid had embraced the disenfranchised culture of blacks, recording songs in their musical style—white and black musical styles were decidedly distinct then—and Elvis Presley’s popularity had soared. Adjacent to a 1960 newspaper article about the expanding protests on Main Street is an advertisement for one of the city’s most prominent record stores, Pop Tunes, with the simple statement RECORDS FOR EVERYONE.

Social issues were not on Jim’s mind when he leased the Capitol, but music was. While Stax was getting into rhythm and blues, rhythm and blues was working its way into Jim. The only music by African-Americans that he’d ever heard had been on warm 1940s evenings as a teenager in Middleton, when he and a date would sit outside the black church near town and listen to the congregation sing. Both soul music and rhythm and blues would grow from church music, reworking the exuberant spirit and exulting lyrics into secular songs. For Jim, Elvis had not done the trick in the middle 1950s, and if his passion for Bob Wills had unwittingly introduced him to blues styles and roots, his conversion to black music had not come until 1959. In the wake of his lone studio success with the Veltones, Jim had shifted his radio dial. “You’re going to listen to the station that plays your records,” he says. “I listened to WDIA and WLOK and I became exposed to black music. When I heard a record called ‘What’d I Say’ by Ray Charles”—the sense of wonder remains in Jim’s voice decades after the fact—“I was baptized in soul music and I never looked back. When I heard that record it was like a lightning bolt hit me, something I never, never felt before. And that’s what I wanted to do, that’s where I wanted to go.” Jim was responding not only to the record’s exciting energy, but also to the deep sense of character that the artist imbued in the music. Like Bob Wills, Ray’s music was embossed with his personality. And that’s why Jim will always discover new talent—he’s not listening for what sounds hot, he’s listening for the individual. In 1960, Jim heard Ray’s new live record, In Person. “That really blew me away. Like the addict, that was the second fix and I was gone, hooked, never looked back from there.” His musical landscape was about to synchronize with his studio’s physical geography.

Rufus reacquainted himself with Jim Stewart and introduced his daughter Carla. Jim showed them the studio that was still taking shape. With Chips Moman, he’d been honing the system, recording Royal Spades rehearsals. They’d gotten to where they could produce radio commercials, and, as Tally had already discovered, they were amenable to being a demo facility for the local professional talent. In addition to the R&B players, they still worked with some of the rockabilly cats, fishing around for something that sounded right. Jim knew about Rufus’s Sun hit, so when Rufus inquired about recording, it was music to Jim’s ears. “When you have a recording studio, you always have disc jockeys that come in,” says Estelle. “You want to take a chance on them because maybe they’ll play some of your other records.”

Not long after—the very next day, by some accounts—Rufus was at Satellite with Carla, his piano-playing son Marvell (then eighteen years old), and Bob Tally’s band, featuring seventeen-year-old drummer Howard Grimes (who would later achieve fame on Al Green’s records as a member of the Hi Records rhythm section). “I had a little four-piece group and we took Rufus Thomas into the studio,” says Tally. “We had this tune we worked on, ‘Deep Down Inside,’ and we got it down so they would record it. And then they had to have another song for the flip side.”

“Daddy had to stay right in the studio and write the other side,” Carla remembers. “Jim said, ‘Let’s cut—let’s keep going so we can get both sides.’ That’s Jim: ‘While we’re on a roll, let’s go.’”

“Rufus,” says Estelle, “he always had a song.”

This song would announce the new studio’s presence, and would introduce a young Booker T. Jones to his future career. “On this song Rufus was coming up with,” says Tally, “I had the rhythm to play a certain way. Do you remember a record called ‘Ooh Poo Pah Doo’? The feel of that rhythm is what I had them do.” Once the drums and bass found the groove, the others could fall in. Marvell was on the piano, so Tally played trumpet; he realized it would sound great with a baritone sax. The vocalist for Tally’s band, David Porter (soon to be one of Stax’s main songwriters), knew a baritone sax player. David was an eager and ambitious young man skipping a day of twelfth grade because he wasn’t going to miss the chance to be in a recording studio.

“I was in eleventh-grade algebra class and David Porter comes with a hall pass and tells the teacher the band director wants to see me,” remembers Booker T. Jones. “David had been singing around the high school and in male vocal groups. We were friends. David had the keys to the bandmaster’s car—Mr. Martin would let David borrow it. It was a ’57 Plymouth, had a lot of pickup. The music-room key was on the same chain, and the baritone sax was in the same room as the bass I always borrowed. David said, ‘Go get your horn, we’re going over to the studio on McLemore.’ I had heard the music coming from behind the curtain while I listened to hundreds of records in the store. I would hang around for hours, and I knew there was something going on back there, but I had never put my foot through the door. So down we went to get the baritone sax out of the instrument room and into the borrowed car and over to Satellite Records and through the door, and there I was.”

“I knew he could play guitar and trombone and all of this,” says Tally, “so we gave him the baritone sax.”

Booker made the most of his opportunity. “Steve [Cropper] played guitar on that Rufus Thomas session,” says Booker. “I knew him because he was the clerk at the Satellite Record Shop. We didn’t have a lot of interaction [on the session] because I was behind a baffle [sound divider] with a little window. But he was the guy. Before I left, I made sure that Steve and Chips Moman knew that I could play piano.” Moman was recording the session. (Though Carla remembers Jim being there, he may not have arrived until the first song was nearly done; if Booker was being pulled out of class, Jim was likely still at the bank. Moman remembers playing the track for Jim that evening.)

The new studio had its first record, the playful “’Cause I Love You,” a back-and-forth between Rufus and Carla, with great dynamic breaks for the piano and baritone sax. Rufus, always a little bit of a clown, is endearing as the man who wants his woman back; Carla sounds very adult (she’d been singing onstage with WDIA’s high school singing group, the Teen Town Singers), and the rhythm evokes the exchange between New Orleans and Memphis.

“We didn’t sit down and say, ‘We’re going with black music,’” says Jim. “‘R&B’ was a foreign word to me. It happened quickly, but not in a manner that was conscious and direct.” The gears of the unimagined machine began to turn when calls came in to the record shop asking for this new song, “’Cause I Love You.” The calls indicated that people were hearing the song and that the store was becoming established in the neighborhood; they weren’t associating the song with the studio in the back, they were just hunting down something they wanted to own. “Locally, we sold four or five thousand records in a couple weeks’ time. We’d never sold that many records on anything.” Rufus’s job at WDIA gave the record a solid tie-in there. “It was so loose back then,” Jim continues. “There was no program director. It was about the friendship with the individual jocks. They played what they wanted to play—as long and as many times as they wanted to play it. It was not uncommon to hear a record played five times consecutively. It was easy to get exposure, especially with black radio. So between DIA and LOK, we broke the record locally. Then Rufus had contacts through the Sonderling Broadcasting chain—he sent the record to San Francisco, it started getting action.”

Jim rode the wave as best he could, expanding his promotion outside the city limits. He found stations east of Memphis in Tennessee, others in nearby Mississippi and Alabama. “Some stations we’d just find the call letters and send the records out,” he says. He and Rufus hit the highway, delivering some in person, hoping the extra attention would be repaid. “So,” says Jim, “we had a local hit.”

![]()

Small independent labels were an essential part of the record industry ecosystem. Able to mine talent in their neighborhoods, cities, and regions, these businesses may have had national aspirations, but they functioned on a local level. Recording a song that sounded like a hit was much easier than distributing enough of those records to make it sell like a hit. And more than one label went broke from a hit, going into debt to keep up with demand, then finding out that distributors who’d ordered all those records wouldn’t pay. The way up and out for the indie was through allying with an established national label. RCA and Columbia, for example, were machines that could readily sell millions of records—the new seven-inch 45s, twelve-inch LPs, and ten-inch 78s—not only in America but also across the globe. An indie would send the master tape of the song to the national label, and the national would incur the costs of manufacturing and distributing; in return, they’d take the lion’s share of the revenue, paying a royalty—10 to 15 percent—to the indie. Smaller labels—Chess in Chicago, Jewel in Shreveport, Dot near Nashville—beat the bushes to find local talent. In many instances, they were farm teams: Memphis’s Sun Records couldn’t keep up with Elvis’s popularity and sold his contract to RCA; Johnny Cash made his name on Sun, but made his money at Columbia.

At Atlantic Records in New York City, Ahmet Ertegun and his brother Nesuhi, sons of America’s first ambassador from Turkey, began building a label that specialized in rhythm and blues. The more established labels didn’t believe the African-American market had enough disposable cash to warrant cultivating; Ahmet, along with his brother and partners Herb Abramson and Jerry Wexler, recognized that their burgeoning popularity was taking it into the white market (first through publishing—the original songs being covered by whites, then by the black artists breaking through). Paramount Records had begun because its parent company manufactured phonographs and it needed product to play; Warner Bros. Records began as an outlet for its movie stars and soundtracks. Atlantic began because it loved the music. As its success mounted—with Ruth Brown, Ray Charles, Big Joe Turner—Atlantic could afford to buy up smaller labels, or sign distribution contracts with them. Smaller and poorer than the major labels, its distribution network cobbled together like a patchwork, Atlantic became an indie that functioned on a national scale.

In Memphis, Atlantic’s distributor was an entrepreneur named Robert “Buster” Williams. He’d fallen into the music business through the vending machine industry. First he sold peanuts at local football games in Enterprise, Mississippi; that led to snack machines, which took him to jukeboxes, and in short order he had a record-pressing plant, Plastic Products in Memphis, which sold records to his distributorship, Music Sales, which sold records to his jukebox company, Williams Distributing. He would make a profit three times on the same record (twice before it left the warehouse), and soon Buster was a ready friend for younger record entrepreneurs like Jim Stewart, extending easy credit on the condition that if any money came in, he’d be paid first—which was easy to enforce since Buster’s distribution company was collecting the proceeds that would go to Jim.

Sales of Jim’s “’Cause I Love You” were brisk enough for the Music Sales staff to notice, and when an Atlantic Records promotions man came through, they brought it to his attention. In short order, Jim’s phone rang and on the other end was Jerry Wexler from Atlantic Records. Wexler’s name may have meant little to Jim, but Atlantic’s name meant a lot—they were the company that released the Ray Charles lightning bolts! When Wexler identified himself as producer of Ray’s “What’d I Say,” Jim realized the call’s significance. “I didn’t know what label distribution was, or a production deal,” Jim says. “The royalty rate Wexler offered was so small that it’s unreal, but it was a start. And that was big time for me.” Atlantic paid Satellite $5,000; the exact nature of that five grand was not etched into the lines of the handshake, and its vagueness would later cause significant problems. One thing Atlantic definitely got for its money was the opportunity to pick up any future records with Rufus and Carla. They released that first one on the Atlantic subsidiary label Atco. The record’s success, the interaction with Wexler—Jim was bitten. “From there,” says Jim, “it just sort of mushroomed.”

It all sounds very matter of course, but it can take years for this series of events to fall into place. There were record labels working out of garages and living rooms all across America, and many great songs never found their way up for air, so receiving a call from Wexler was a very big deal, and hearing him say you’d done something that he wanted a piece of was a significant indication that you were doing something right.

Not that that made Jim’s work any easier. Jim was working his day job at the bank, nights and weekends at the studio, and also gigging in clubs. (Steve says Jim used to sit up nights and calculate royalties down to the penny.) Word about his facility was getting out—the room was large and the sound was good—so musicians would book time there to cut demos, the small-change payment reverberating through the empty coffers. Someone might find an account and they’d cut a furniture commercial or radio spot of some kind for cheap. Chips, who was overseeing the studio while Jim was at work, ran deep in the music community and could pull together a jam session, and had an ear for pulling songs from rough ideas. “Usually it was just someone that would walk in,” Moman remembers. “That’s how David Porter came in. And William Bell. After school was out, Booker would come in wearing an ROTC uniform—him and David Porter. We’d just start recording. When Jim would get off in the evenings, I’d play him what I did that day.”

When no one else was there, the Royal Spades were ready to make noise. “Hanging out there was like going to Disneyland every day,” says Don Nix, who often came in earlier than the other kids because he’d either skipped school or been kicked out. “What a education that was. If you didn’t do anything else, you stood in the record shop and listened to records. And every day was something new. Jim didn’t know anything about recording equipment, and I’m not sure that Chips knew that much—just enough to get a one-track machine and some microphones up and running, kind of hit-and-miss. There was a lot of recordings at Stax that never saw the light of day. They weren’t all hits, and some of them weren’t even records. But there was always somebody cutting something. You’re at the right place at the right time and the right stuff happened.”

When Estelle opened her record counter, Steve Cropper quit his job at a grocery store to work for her. Steve was always more serious than the other guys in the Royal Spades; he was a natural leader, he had a tendency toward the staid and reserved, but like his bandmates, he liked his music loose and fun. He was attending college and may not have been anticipating a career in records, but he knew that working at Satellite kept him closer to the studio than the grocery did. “We didn’t get paid very much for playing music in those days,” Steve says, “and I had to eat. I talked to Miz Axton about working in the record shop, and my main reason for that was to be close to the studio—that’s what I wanted to do.”

Jim, too, had found what he wanted to do, even if the monetary rewards were not yet evident. “Music can bring people together, emotionally as well as socially,” he reflects. “You begin to see inside of each other’s minds and understand where we came from. We were looking for good talent, it didn’t matter how old, how black, how white. We were looking for good writers, good musicians, creative people. Once we opened the studios on McLemore, I don’t think we cut any more pop or white records for a long time. It was as if we cut off that part of our lives that had existed previously, and never looked back.” That change may have been market-driven—Jim’s white records had flopped, his black ones had sold. But there were plenty of white people who couldn’t have worked with African-Americans, no matter the success. Jim was feeling the power of the music in his soul. “As it grew, it didn’t matter whether I was getting encouragement. It was striking an emotional fire within me and that was all I was going by. I had no way of knowing whether it was going to be successful or not, I just knew it moved me.”