Some days the studio felt like a bad talent show, people hoping to be the next Carla Thomas—but their tenth-grade songs sounded like tenth grade, their performances juvenile. A neighborhood doo-wop group cut a pretty good piece with Chips Moman that Jim felt was worth releasing. The group renamed themselves for the producer; Atlantic did not pick up the Chips’ “You Make Me Feel So Good,” but it was a worthwhile exercise for Satellite. Everything was; it was all so new.

Chips kept the studio active. He had a good ear, and plenty of time to audition those who felt they belonged in the studio making records, not in the front buying them. One player who made his way to the back was Floyd Newman, a saxophonist who had recently returned from college in Detroit. His family lived near the corner of College and McLemore. Last he’d seen, white people were watching movies at that address; four years later, black people were dancing outside the front door. “It was a record shop, and I went in there to buy some records,” he remembers. “Some of the musicians saw me and they hired me.” Floyd hung out with his old friend and fellow saxophonist Gilbert Caple, and they came up with a riff. “Gilbert and I, we were just messing around,” Floyd continues. “Goofing off. And I happened to put in that response, ‘Ooh, last night.’ It had the feel, and the feel is what sells songs.” Chips heard a song beneath the fun, and he put Gilbert and Floyd with Packy and his rowdy friends; Gilbert and Floyd were black, a bit older, and they could really play. So could some of Packy’s friends, but not all of them. Chips brought in his honky-tonk friend Jerry Lee “Smoochy” Smith, who had a piano riff that seemed like it would meld with Gilbert and Floyd’s idea, and it did.

“We were just kids having a good time,” says Wayne. “Poor old Jim, it was life and death to him.” Chips could corral and focus their energies. “Jim was a nervous fellow,” Wayne continues, “took nerve pills. A country redneck fiddler in a black neighborhood—a banker really. And working on borrowed money. But Miz Axton was selling 45-RPM records to black kids and she knew they wanted to dance. She told us, ‘I want you to make a record these kids can dance to. And I want it to be an instrumental.’ So that’s how we came up with ‘Last Night.’” Wayne’s use of “we” is casual, but exactly who the “we” was would soon become a heated conflict.

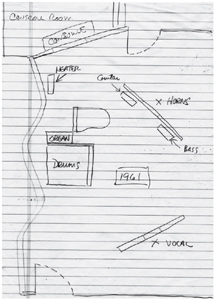

The studio setup in the early 1960s. (Drawing by Steve Cropper/Courtesy of René Wu)

With the rehearsals taking shape, Chips called a recording session. Steve Cropper was on the session, and Duck Dunn was supposed to be, but his father had recently lost his job and, to earn money, he was working with a friend giving helicopter rides on weekends. “My dad was going through financial stuff,” says Duck. “He needed help.” Duck was giving other kids a thrill and missing his own. On bass was Lewie Steinberg, another older black player who, at twenty-seven, was active in the nightclub scene; he played with Al Jackson Sr.’s band (alongside Al Jr.), and with Willie Mitchell’s band (where Al Jr. also played, and Booker often subbed). “I was at home minding my own business and Gilbert Caple come by my house,” Steinberg says. Caple, one of the new song’s writers, invited him to the studio. “I said, ‘What studio and for what?’” Steinberg hadn’t been to Satellite yet; in fact, he’d just come from a tour through Louisiana, and his playing was saturated with a New Orleans feel that he lent to the song’s bottom.

Somewhere between the country soul of Chips and Smoochy and the funky hearts of Floyd, Gilbert, and Lewie, the song “Last Night” emerged. It is, perhaps, the archetypal Memphis song of that era, the “What’d I Say” for locals. The horns tease out their opening notes, so playful; the rhythm—it’s surprisingly layered, like a comic team’s banter, and much too kinetic to hear without physically responding. The drummer (Curtis Green) was from the Plantation Inn and his playing suggests how raucous and fun that club must have been. As gleeful a song as ever recorded, the instrumental is punctuated by Floyd’s occasional vocal refrain—“Oooh, last night!”—hinting of salaciousness, of secrets being told between friends. It is fun, funkified.

The sonic quality of the record is also great—it leaps out of the speakers, etched hot into the tape, with the needle in the red but not distorting. “Chips was actually at the controls,” says Jim of the production. “Insisted on it. Two little four-channel mixers tied together, and a little Ampex mono machine.” It’s a poker player’s recording, not a banker’s.

Before its release, the tape sat on the shelf for weeks. Jim pursued his recordings with Carla, and Chips kept the studio humming. Time passed, the tape languished, an exercise in recording, another testing of the equipment. And that might have been the end of the story but for one important fan: Estelle. She heard the record’s blend of rhythm and blues and country, and knew, too, that instrumental songs were popular (it was thought by many that Hi Records stood for “hit instrumentals”). “I was selling those blues numbers,” she says, “and I could put two and two together.” She had Jim make a test pressing for the store’s turntable. “I had become close to WLOK and WDIA, talking to the disc jockeys,” says Estelle, referring to the two black music radio stations. When she played it for one of WLOK’s lead jocks, he took the copy to the station, swearing it was a hit. “From the very first day he put it on,” Estelle says, “people began stopping at the shop looking for that instrumental. They’d say, ‘I don’t know what it is, but it goes, “Ooh, last night.”’”

While the requests continued, Jim’s attention was on Carla. He heard pop potential and took her to Nashville. “I thought I’d get a better string sound,” he says. “I was misleading myself, actually. I didn’t know what I had in that studio.” Soon he’d recognize the difference between the foothill sound of Nashville’s country and the thick funk of Memphis’s swamp, vowing never to cut an R&B record in Nashville again.

“Jim was so involved with Carla and the other vocalists,” Estelle says, “he wasn’t pushing this instrumental bit. But because my son was in there, I was pushing that instrumental. They’d played it on the radio and they were coming into the shop to buy it but I didn’t have a product. It was getting very irritating.” Estelle believed it could sell nationally, and she played it for Jerry Wexler. “Mr. Wexler said, ‘It’s all right, it needs this, that, and the other.’ He used to say, ‘Just because it’s selling in Memphis doesn’t mean it’s a national hit.’ I said, ‘Mr. Wexler, I know enough about the record business in Memphis, Tennessee, that if it sells here, by God it’ll sell anywhere in the world.’ This was the hardest market. I knew we had a product that would sell, and I knew we needed the money, and here we are wasting that time.”

Weary of telling customers that the record wasn’t available, pining for the easy income, Estelle made a decision. “One night I was in the record shop, didn’t close till nine, my husband standing there anxious to go home. I said, ‘Nope, I’m not leaving here tonight till we settle something. We’re either going to put that record out or we’re going to pull that dub [copy] off the air.’ Jim and Chips came up about nine o’clock. Started out, I asked them in a nice way about the record. They began to hem and haw. Then I started crying, trying to get their sympathy. That didn’t work. I started cussing and my brother had never heard me cuss before. I blew his mind. He said, ‘All right, in the morning have Packy get the tape and take it to the plant for mastering.’ When I believe in anything, I’m going to keep on until I get it done.”

The next day, Estelle had no trouble rousing the usually indolent Packy. “Packy went back to get the tape, starts to play it, and would you believe that about sixteen bars off the front end of that tape had been erased? We found out that they had taken that tape to Nashville when they cut Carla’s album, and someone had erased that up there. I said, ‘As many times as y’all have done that tape back there, there’s got to be another one with the same tempo.’” She adds, “To this day, I know exactly where the splice is in that record.” Before releasing it, Estelle insisted the band change its name; all-white kids playing black music and calling themselves the Royal Spades just wasn’t going to play. She suggested the Marquis. Words with a q, however, intimidated some of the band members, and this word—meaning noblemen—seemed unrelated in any way to the boisterous group. Estelle considered the movie marquee that hung over the front of the building, and the keys of the piano, and she overcame the challenge of the difficult letter by suggesting the Mar-Keys. Ah, phonetics. The boys could drink to that.

“Nobody ever thought it was a record,” muses Don Nix. “And it wouldn’t have been a record had it not been for Miss Axton.” “Last Night” caught on quickly, going from a popular unreleased song on local radio to a regional and national hit, easing its way to number two on the R&B chart, number-three pop.

“The first time I heard that song on the radio,” says Wayne Jackson, “I was driving to a gig and just as we got to the bridge on Lamar, it came on the radio. I damn near wrecked the Plymouth. It’s a onetime thing, like sex—there’s only one first time when you hear yourself on the radio, something that you don’t expect to have happen. It just lit me up, and I’ve been lit up ever since.”

“Jim realized that Estelle had her finger on the pulse of what was going on,” says Steve, and Don Nix adds, “They started listening to her after that. And she started having a little bit more say.”

“When we put that record out,” says Estelle, “it exploded like nothing had exploded before. I sold two thousand one by one over my counter. They certified a million, it was a national hit, and I’ve never been as proud of a record in my life.”

![]()

While much good came from the success of “Last Night,” it also marked a certain loss of innocence, the recording business emerging from the recording sessions. First was the issue of authorship and its rewards; then, who would reap the glory on the road. The authorship question was tied to the publishing royalties, a long-term issue; the glory was short-term; both were financial. The money from a hit goes to the songwriters (collected by their publishing companies) and, if the artist has a good contract, they share in some of the royalties on uses of their master recording. Many artists never see a dime after they get the union pay for the session, and that’s the case with the Mar-Keys; those who played that day got paid, and most never saw another cent from record sales. But the songwriters continue to be paid—for every record sold, for every use licensed, for every new version recorded—and after being certified for a million, it has continued to sell, and to this day is licensed for movies, TV shows, commercials, games, and has been covered by other artists. Each of those usages is money for the songwriters. Saxman Floyd Newman is adamant that the authors of “Last Night” were solely him and Gilbert Caple. “We were just messing around and that’s the way a lot of hits come up,” says Floyd. “Two people wrote ‘Last Night.’ Gilbert and I.”

When the record came out, there were three names on it in addition to Gilbert’s and Floyd’s. The piano part is essential to the song, and it came from Smoochy Smith; his name is on it. Moman, as the song’s producer, brought the piano riff to the horn riff, fashioning one song from many pieces; that’s part of the producer’s job, but his name’s on it as a writer. The final name is Packy Axton. Packy didn’t solo, didn’t really contribute anything essential; his name is there because his mother could put it there, because she saw others carving their piece from the publishing, knew that other label owners who couldn’t hum a tune had affixed their names to songs—and so she put her son’s name on it. (“I couldn’t even spell publishing then,” says Wayne, “much less have asked to be included in it.”)

Gilbert and Floyd weren’t around when the credits were being divvied on their song, and they might not have gotten anything but for the virtue of an unexpected someone: the cranky Everett Axton. He spoke up for the artists. “He called us outside,” Floyd explains, “said, ‘I want you to know that you gonna get your money, and nobody gonna beat you outta your money.’” He was mostly right: “Instead of Gilbert and I getting fifty percent each, we get twenty percent,” says Floyd. “A lot of money’s been made off that song, and I’m glad Everett Axton spoke up, ’cause we were gonna wind up with nothin’.”

Bright lights beckoned, or dim lights did, and smoky rooms smelling of stale beer. The band went on the road to promote the new song. Or a version of the band. That is, not the band that recorded it, but the band that smoked in the Messick High School dungeon, that played for sailors at Neil’s, that helped Jim test the wiring in Brunswick, tore out the seats in the Capitol. It was approaching the summer of 1961, and most of the boys revved their engines and spun their wheels waiting for their drummer Terry Johnson to finish twelfth grade and be dismissed for summer break. Then they’d hit the road. The label sent Carla out with the boys, and Miss Axton to chaperone, in a late-model Chevrolet Greenbrier that she signed for, and on which the boys paid the note.

“We were very young and life was magical, especially because we were playing music,” says Wayne. “No one ever said, ‘You’re gonna take that trumpet and make a living with it.’ My band director, all the people in Arkansas—nobody. They said, ‘How you gonna plow with that thing, boy?’ We never expected to get off the dirt farm, and it was magic when it happened.”

The communal ideal of the Mar-Keys with Carla and Miz Axton soon collapsed; traveling with eight teenage boys was not an environment for ladies of any age or type—well, except for one type. After the first run of dates, the Mar-Keys slowed the van and the women jumped out near home. With no chaperone and no Carla, it was, Steve laughs, “like letting a bunch of monkeys out of the cage.”

But this was no picnic at the zoo. The band that went on the road—the white guys—didn’t include the two black guys who’d cowritten the hit. “‘Last Night’ became a hit record and Jim didn’t send me and Gilbert,” says Floyd. “He sent all the white group out on the road, a bunch of kids. And I never thought that was fair, not at all, because Gilbert and I was a part of that group, but we were black. They had been out there for quite a while before we found out.” There is truth in what Floyd charges, though there was also a benefit in sitting out this tour: He was finishing college, training to be a band teacher, and as exciting as the variety of stages would have been, he’d have been one furious and frustrated college guy as he watched the Mar-Keys squander, in an alcoholic frenzy, most every opportunity presented them.

“You had eight guys between the ages of eighteen and twenty who just wanted to get out on the road to play and party their butts off,” says drummer Terry Johnson. “And that’s exactly what we did and that’s probably why the band was a one-hit wonder. It’s hard to be a two-hit wonder when you leave the Dick Clark show and he’s waving at you on film and everybody’s shooting him the bird. It’s hard to be more than a one-hit wonder when you’ve got a tour of Texas booked and the whole band takes off to Mexico and then calls back and says, ‘We’ve lost our bus because we sold it.’ We wanted to have fun, chase women, drink beer. We did it the storybook way and to hell with the consequences. ‘Let’s have this memory burning in our brains when we’re sitting in the old folks’ home, incontinent.’”

They played it for all it was worth, working the road and pushing the record up the charts. “We played on top of the popcorn stand at the Sunset Drive-In in West Memphis,” says Wayne, and his smile is so big that it almost reaches back in time. The roof was slanted backward; Packy set his bottle down, and as it started sliding back, he chased it, tumbling off the roof onto the gravel below. The bottle didn’t break, nor did Packy, but he refused to return to a place so inhospitable to bottles. “We played the New Moon Club in Newport, Arkansas, where they had chicken wire around the bandstand,” Wayne continues. “We didn’t know whether it was to keep the musicians from getting in the crowd or the crowd from throwing bottles at us. If they had told us to play in the sewer, we would have crawled down in there and played. We were making money, for God’s sake! I was eighteen when all that happened. I had been working at the Big Star grocery store in West Memphis making eighteen dollars a week and tips. And I had a paper route too. I made as much in a night onstage as I made in a week at the grocery store.”

They’d show up at black clubs and the owners would be very skeptical that the eight pimply white kids pouring out of the Greenbrier were the ones who could play the record they’d been looking forward to hearing. But when they took the stage, the band earned the audience’s respect. A club didn’t need the precision of a studio band, and these guys were full of passion, hot as fire, and they had the feel. Playing black music for black audiences is where these kids had dreamed of being since they’d heard bands like the Five Royales, Hank Ballard, and Bo Diddley. They’d been motivated by the liberation they heard in the music, the looseness released in a society that was otherwise so constricted. Their motivation was the good times, and if there was any social result, that was accidental. “People who had never known each other, who had never eaten a barbecue together, who had never done the things that typically people do,” says Terry Johnson, “all of a sudden were doing those things.”

Fun as it was, eight guys in a Chevy van was a petri dish for tensions, their personality differences incubating. Before too long, a noble fight was brewing among the Mar-Keys for leadership of the band. “I used to wear white socks, march around in ROTC,” says Duck. “And so did Don Nix. But, you know, we were just rebellious. Steve was a little different. Steve was pretty strict and disciplined and I commend him for that.”

On the one hand, the guys could rib Steve and he could take it. “None of us liked to pack that Greenbrier,” says Don. “But Steve was really good at it. So we’d make a little effort and then say, ‘Gosh Steve, how do you make all this fit?’ And he’d push his way up there and we’d all stand around smoking cigarettes every night while Cropper packed the van.”

On the other hand, Steve could not tolerate the complete lack of discipline that defined Packy. “One night we all got in a bar fight and it was because of Packy,” Duck remembers. “While we was on a break some guy made some insinuations about Packy, and Packy slashed the guy’s tires and this guy pulled out a twenty-two rifle—looked then like a twelve-gauge shotgun—and a fight broke out. Some lady got hit, the owner’s wife—it was just a complete misunderstanding. A drunken brawl is what it was.”

Most galling of all (to Steve), Packy considered himself leader of the band—when Steve had the band long before Packy joined and was obviously the responsible one. Packy cared nothing for responsibility, but he made it known that they’d be nowhere but for his mama, so it was his band. “These guys went crazy on the road,” Steve says. “It was just pure unadulterated madness. So we’d come down through Myrtle Beach and were in Bossier City, Louisiana, playing the Show Bar.” This was a strip joint where the band played behind and above the bar, and a schoolteacher on summer vacation would shimmy herself down to her nipples while the band coaxed the audience toward frenzy. “We had a three-week engagement,” Steve continues, “and somewhere in the second week we went to the bathroom on a break and I looked at Packy and I said, ‘Packy, you got it. I’m gonna turn it over to you.’ I said, ‘I can’t take this anymore, I’m going back to college.’ I caught a bus, headed back to Memphis, and got reenrolled in Memphis State. And I asked Miz Axton for my old job back in the record store, which she gave me.” Steve went home to Packy’s mama.

The success of “Last Night” wrought another change: In September 1961, Satellite changed its name. When the record reached California, another label there named Satellite learned of the Memphis operation, and they sent a wire ordering Memphis to cease, but offering to sell the name for a thousand bucks. “I said, ‘Screw that, I hate that name anyway,’” Jim remembers. “And the next pressing of ‘Last Night’ we changed to Stax. My wife came up with the name, from Stewart-Axton.” Combining the first two letters of Jim’s and Estelle’s last names, “Stax” cleverly conveyed a proprietary sense while evoking the stacks and stacks of records they hoped to make and sell. The label’s emblem was a stack of records in motion.

The Mar-Keys roared on down the road. Since they hadn’t played on their big hit, the studio didn’t need them around for their next release, or their next several. Fumbling around some no-name town, they entered a record store and saw they had a new single on the market. “The second one sure as hell couldn’t have been us because we were gone the whole time!” says Terry. “But Floyd Newman and those guys, they put a nice one together.”

When neither “The Morning After” nor “About Noon” got the same response as “Last Night,” the theme was retired. The band, however, forged on, running on gas, running on fumes, then finally running empty. “The Mar-Keys died in St. Paul, Minnesota, on a cold fall morning when eight guys looked at each other and said, ‘It’s over,’” says Terry. “And then it looked like rats leaving a sinking ship.”

![]()

“Last Night” had, essentially, walked in off the street. “We were surrounded by talent after we moved onto McLemore,” says Estelle. “The neighborhood had become a black area. In our little hometown [Middleton], I doubt there was half a dozen black people in the whole area. When I taught school, we didn’t have integration then, and not much at the bank. At the studio, we just looked at people as talent, not the color of their skin.”

A dozen singles were released in the six months after “Last Night,” and another one that walked in the front door also hit the charts. Stewart and Moman had regular players they could call on, and sessions were mix and match depending on availability. When the Mar-Keys were home for a break, some of them were called to help William Bell record an unusual tune, “You Don’t Miss Your Water (Till Your Well Runs Dry).” It was a country music ballad that had been baptized in a black church feel. (Later it would be covered by soul great Otis Redding and country-rock pioneers the Byrds.) William was one of the kids who’d been dancing on the sidewalk when Estelle hung speakers by the front door. He’d been singing with the Phineas Newborn Sr. Orchestra, one of Memphis’s premier club bands and a training ground for many future stars. In 1960, the orchestra lucked into a six-week club date in New York City, and when it was extended to three months, Bell, homesick, became aware of what he’d taken for granted in Memphis. Using the metaphor of a foolhardy lover, the twenty-one-year-old wrote about his pining. The following year, he was making plans for a medical career—like his father wanted—when he encountered Moman, who’d been impressed by Bell in the clubs; Moman invited him to audition at Stax. “I had been to Stax to sing backing vocals on ‘Gee Whiz,’” William says. “And I knew Estelle because she had the record shop. And I knew Chips Moman. So I was comfortable in that atmosphere.” Under Moman’s direction, Bell imbued the song with longing, and it has remained evergreen, a song through which you can hear life whispering urgently: Appreciate the fleeting moment, it is a gift.

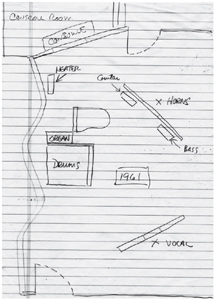

Before the music business took hold of him, William Bell intended to be a doctor.

The song came out in November 1961 with Atlantic’s muscle pushing it; everything Stax released now had a shot. It got just enough attention to be lingering in January after the rush of Christmas records. Its sound was new and nostalgic, cloaked with a melancholy appropriate for winter. “Starting in January, it just skyrocketed,” says William. “The first city that it hit in was Baton Rouge and then New Orleans and Pensacola.” Atlantic had the reach to build city upon city, and it did. “I think Jim thought it was a little bit too churchy,” he continues, “and he wanted the up-tempo stuff that he had been selling.” It hit Billboard’s Hot 100 in late April. Jim had released it because Moman and Estelle pushed him; with the sales building, Jim came around.

![]()

Success, as it does, brought bubbling tensions to the surface. Expenses had gone up with the new location, and they’d been operating on a tight budget. Estelle counted on Packy for help before he went on the road. “I was depending on my son to open up while I was at the bank. He’d finished high school, didn’t want to go to college.” Giving Packy the responsibility of the keys, Estelle knew, meant accepting a responsibility herself: “Usually I’d have to call him from the bank to get him up to go open the doors.”

Two things about that situation grated on Jim. “Nepotism always bothered me,” he says. “But Packy, there was no question—Packy was not an organizational man. You can’t put people in positions if they can’t do the job. Packy would show up one week and the next week he’s gone. He was not reliable, and he didn’t want that responsibility either. But my sister always tried to give him the responsibility. She wanted him to be head of the studio. That would lead, in my opinion, to total destruction.”

“Mother was fighting for something that was never to be,” says Doris, Packy’s sister. “But that’s what parents do. He was so talented, but he didn’t have that management sensibility.”

Jim’s business couldn’t survive on shenanigans. “She brought her family into the thing, and that clouded her perspective,” he says. “She thought I was just a cold bastard. But it was nothing personal. I was looking out for Stax Records. If it’s good for Stax, it’s good for her, it’s good for me, it’s good for everybody that works there.” And what was good for Jim was to give Chips more responsibility. “When we moved to McLemore, Moman and I were very close,” he says. “Chips was my right-hand man. I was still working at the bank, Chips would open the studio, take care of whatever we needed.” But there was a problem. “My sister didn’t get along with him at all.”

By late 1961, her record shop had become successful enough, and demanding enough, for Estelle to quit her job at the bank. “At one point, the doctor put me in bed for three days, nothing but nerves,” says Estelle. She’d been juggling two careers and home life. “I had two kids in school, was leaving home about six thirty in the morning to get to work on the bus. Leave there at four thirty, get to College and McLemore at about five, stay till nine o’clock. When I came home from that, I had to get clothes together for the kids to go to school, do what I had to do in the way of housework—and it got the best of me. There wasn’t a minute for anything extra. Doctor said to me, ‘You’re going to have to get rid of one thing or another,’ so that’s when I left the bank.”

When her Stax hours increased, so did the tension with Moman. Chips and Estelle were from different worlds. Estelle had a vision, and a practical sense for actualizing that vision. She’d proven her mettle at the bank, and she was set on proving it again in the music business. Chips also had a vision, but his approach to achieving it was unlike anything Estelle could comprehend; his nickname, after all, came from his poker playing. (“Chips would rather go to a two-dollar card game,” says Duck, “than produce a million-selling record.”) Estelle remembers Chips living beyond his means: “Chips loved to drive fancy cars. He’d have them financed, then he’d run to keep from paying notes. You could always tell when they was after him.” Further, Estelle didn’t like Chips’s friends. He was someone who liked a drink, and in this beatnik era, she suspected his friends might be into other, more criminal recreations: “I’d be kind of upset at the characters that were coming in and out of there in the daytime. Jim and I talked about the drug scene, which was just opening up. If the law caught ’em, it’d be the end of our place. And we didn’t want to have the name that we were harboring drug addicts.”

When Jim would arrive after work, he’d find himself in the middle. “I would get the flack when I walked in the door,” says Jim. He speaks of Chips with respect and admiration, though they too were very different: Chips was a gambler, Jim was a conservative banker. Chips played electric guitar with an ear for rock and roll, Jim played the country fiddle. Chips was headstrong—working under Jim for Jim’s company.

By early 1962, the fighting came to a head. Chips had recorded an instrumental, “Burnt Biscuits,” an exchange between a popping organ and a harmonica, that he thought was every bit as good as “Last Night” and better than the other Mar-Keys singles that had followed. He named the band after the car he was driving, the Triumphs, and just like he’d hoped, it was gaining traction in Memphis and a couple other cities as well. The single inaugurated Stax’s first subsidiary label, christened Volt Records. (A subsidiary allowed a successful label to spread out; in the wake of the 1950s payola scandal, radio stations were careful not to show favoritism and avoided playing too many songs by one label, no matter how good those songs might be. Subsidiaries allowed for a pretense of fairness: Chess Records formed Checker; Atlantic had Atco. Stax established Volt.)

Chips believed “Burnt Biscuits” had been a hit, but the payment he got from Jim didn’t reflect that. Chips told Estelle that Jim was beating him out of his money. “I knew better because I had seen the sales on it,” says Estelle, “so he and I got into it. Chips told Jim that I was trying to run the business, and Jim jumped on me. I told Jim, ‘I defended you. Chips accused you of stealing his money on “Burnt Biscuits.”’ That didn’t sit too well with Jim.”

Moman had proved himself a strong engineer and producer, and as reassuring as that was, it was also something of a threat. Jim wanted to be a producer too, not an executive. “I could see Chips taking over,” Estelle says, “and I didn’t want that taken out of Jim’s hands.” Jim knew he couldn’t handle the studio while working at the bank, and despite the successes (mostly recorded under Chips’s hand), the company was far from strong enough to support him and his family. Jim needed help. And there seemed to be a new solution: Since returning from the Mar-Keys road band, Steve Cropper was proving himself reliable, resourceful, and friendly. Steve was a quick study, absorbing technique from both Jim and Chips. He was the support that Jim needed, both less threatening and more dependable. So when Chips got hot about the money from “Burnt Biscuits,” Jim felt safe in letting Chips go.

“I was supposed to get a third of the Satellite label,” is how Chips recalls the setup. He’d turned the label from schmaltz to popular music, and he’d been the force behind several of their biggest hits. “We had two or three records goin’ at the same time. It started getting to be a madhouse. And I wrote one side of Carla Thomas’s ‘Gee Whiz,’ and I wrote one side of ‘Last Night.’ And so I asked Jim about my money, and he said, ‘Well, the only thing I can tell you, Chips, is I’m fucking you out of it.’”

Wayne Jackson was sitting in the lobby when what he describes as “the explosion” occurred. “Jim and Chips came into that hallway in a snit. They were at each other. Jim just put his hands on his hips and said, ‘Well if I screwed you, you’ll have to prove it.’ And Chips said, ‘Well, okay then,’ and he slammed out the doors, got in his TR3, and purred on off down the street.”

“I hated to see him go,” says Jim, “but I was in the middle. I ran the company with an iron hand, and I had to. I had to.”

A new calm followed. Jim no longer had to play referee between Chips and Estelle. Steve moved into Chips’s place in the studio. Packy was finally doing something he was good at—leading the besotted Mar-Keys, with plenty of miles between him and Jim. And Chips acquitted himself quite well, though he had to pull himself up from the mire. He got a lawyer who got him a $3,000 settlement. “I was a broke kid,” says Chips. “A thousand of it went to a lawyer. [Leaving Stax] is a bad memory. It affected me all the way through.” It did, however, let him know he wanted to be in charge. After a year in Nashville, Chips opened his own studio across Memphis, American, and became a huge hitmaker through the 1960s and ’70s, responsible for some of Elvis Presley’s best-known and respected work, as well as hits with Neil Diamond, Wilson Pickett, Dusty Springfield, and Waylon Jennings—among many others. Working for himself, everything he touched turned to gold.

Steve picked up the daytime responsibilities, as much as college allowed, until something had to give, and it wasn’t going to be music. “I wound up marking tapes and sweeping the floor, cleaning the piano and doing whatever I could do,” he says. “I didn’t mind calling the musicians or going to their house and waking them up. And I turned in the contracts, edited tapes, and did all of the little odd jobs that nobody else wanted.”

“With Steve,” says Estelle, “Jim didn’t have nearly the headaches that he had before.” Nor did he have the experienced assistant he’d had before, the hitmaker. Jim had cut “Gee Whiz,” and now he’d have to prove that that wasn’t a fluke.