The little studio hummed along. Estelle would open the record shop and Steve the studio. Customers entering the old theater doors could be coming in to buy a song or to make one. Buying one was easy, and making one not much more complicated. Steve would audition the talent and, if it seemed like something was there, he’d have the room ready when the band would fall by. “People were always coming by the record shop and saying, ‘Could you hear me sing?’” says Steve, “‘Could you hear me play? Would you listen to my song?’ And usually during the week there were sessions going on.” By the time Booker showed up after school, Lewie and Al were there. They might have a radio ad to knock out, a job sent by a local ad agency; a producer or musician might rent the studio, sometimes bringing his own staff, sometimes hiring the band and engineer. If Steve had heard something good, there’d be fresh tape on the machine and a nervous kid—or adult—from the neighborhood, pacing about. If no one had a seed from which a song might grow, they’d gather around the turntable in Estelle’s shop, let her play them the most exciting singles she’d recently found, and then parse the trends and melodies, finding something to build on. There was forward motion, but no overarching direction.

In August of ’62, they got stroked a little. A record promotions man named Joe Galkin, based in Atlanta and a fan of Estelle’s shop and Jim’s studio, booked a session for an up-and-coming act. Talent coming all the way from Georgia! Galkin was familiar with the studio because Memphis was part of his territory. Promo men worked as hired guns for national labels, making sure that in specific regions (like the South) their records reached the front lines of the disc jockeys and retailers. Joe watched Stax grow, and was impressed by the players. “Joe was promoting records for Atlantic,” says Estelle. “That’s how he came in the picture. We’d talk about records since I had the shop. He recognized the product we were putting out was very successful.” Joe had watched a regional guitarist, Johnny Jenkins from Macon, build a following with his local instrumental release “Love Twist,” and when it kept on selling, he brought it to Atlantic, which gave it national distribution. Sales were strong enough to warrant a follow-up, and Galkin hoped to marry the success of the “Green Onions” sound with Jenkins’s flashy guitar.

On Sunday, August 12, 1962, the group now calling themselves the MG’s was out front beneath Estelle’s record-store speaker. The temperature was pushing ninety but not breaking it—a relatively mild summer day, though hot and thick enough to remind Memphians of their city’s proximity to a swamp. Air conditioners were still not common, and the studio had no windows, so waiting out front was not just hospitable, it was also a relief. “We’re all out there,” says Steve, “and here comes this car, Georgia plates on it. We go, ‘Well, that’s gotta be them.’” “Them” was two people, a star and a driver. Johnny Jenkins was tall and slender, fashionably cool and laid-back. The driver, an African-American, set to work. “This big, tall guy gets out of the driver’s seat,” Steve continues, “goes around to the trunk, and he starts pulling out amplifiers and microphones and guitars, like he was setting up for a gig.” Steve told the driver that, this being a recording studio, they had their own equipment inside and, in fact, it was already set up.

“I remember them pulling up,” says Booker. “I remember the driver being the guy that carried the stuff—the food and the clothes—for Johnny’s demo session.”

Johnny’s demo session—how quickly the excitement faded. Jenkins was a showman, a guitarist who danced, did acrobatics, put the guitar behind his head and played solos. His live show was all fire, and when people left, they wanted a reminder of the fun, which they could get by purchasing “Love Twist.” But creating a new record that would draw people to the show—that proved harder. His showmanship and the MG’s groove couldn’t find a place to synchronize, the session never hit its lick, and it was ending in disappointment. The players had gigs, disbursing to play “Stardust,” “Roll with Me Annie,” and “Apple Blossom Time” to good citizens sipping highballs and swishing across the dance floor. Hits or misses in the studio notwithstanding, these guys put food on their tables by playing in clubs.

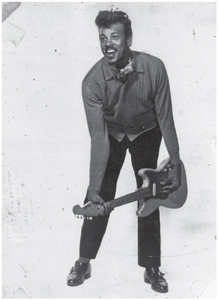

Johnny Jenkins, left-handed guitarist, 1963, dancing the “Love Twist.”

“During the session, Al Jackson says to me, ‘The big tall guy that was driving Johnny, he’s been bugging me to death, wanting me to hear him sing,’” Steve remembers. “Al said, ‘Would you take some time and get this guy off of my back and listen to him?’ And I said, ‘After the session I’ll try to do it,’ and then I just forgot about it.”

“He had really sat over there all day long,” says Al, “and he kept talking about, ‘I can sing.’”

The guy had made no impression on Jim during the course of the day (the session was scheduled around Jim’s bank duties). But Joe Galkin, who was sitting in the control room with Jim, had heard him sing as part of Jenkins’s club act, and he was hoping to leave the session with a twofer—two records for the price of one. Now that Johnny hadn’t jelled, he was in danger of leaving the session with nothing. “Joe and I had a great relationship,” Jim continues. “He’d scream at me and I’d scream at him. We were great friends.” The vocalist was badgering the band, and Galkin was working Jim. Almost too late—some of the guys were packing up for their night gigs—Galkin played his trump card. He’d give Jim half of the publishing royalties in return for half of Stax’s royalties on sales of what they cut. The publishing was worth more: It would begin paying with the first sale, and would pay on others’ versions should they be recorded, while the master royalties wouldn’t pay until the expenses had been recouped, and applied only to this version. “Everybody was tired and a couple of the musicians had already left,” Jim continues. “It was like, ‘Well, we gotta do this. The guy’s been sitting here waiting all day, let’s see what he sounds like.’”

Steve called the guy down to the piano. He asked Steve to play some “church chords.” “‘Church chords,’” says Steve, “meaning triplets. And we started playing and he started singing ‘These Arms of Mine’ and I know my hair lifted about three inches and I couldn’t believe this guy’s voice.” Steve ran outside to wrangle the departing musicians. “Lewie Steinberg was putting his bass in the trunk of his Cadillac,” says Steve, “and I said, ‘Lewie, get your bass out, man. I need you real quick.’ Al Jackson was there and Johnny Jenkins wound up playing guitar since he was already plugged up. So we cut ‘These Arms of Mine.’”

“When you’re in a moment like that, you’re not thinking that it’s gonna sell a lot of records,” says Booker T. Jones. “It’s all heart, and time gets frozen. I’d never been with anybody that had that much desire to express emotion. ‘These Arms of Mine,’ it’s the longing. And it translates to the listener and the player and anyone who hears it. When that happens, millions of people listen. There’s no choice.”

“He was a very humble person,” says Estelle. “I don’t think he had any inkling we’d even pay attention to what he did. But we were always analyzing people for their uniqueness, and he was definitely different from anyone else we had. He had that different sound. But we didn’t think he’d bust it all wide open.”

The driver’s name was Otis Redding.

![]()

Nobody at Stax knew at the time that Otis had already recorded two singles, one in California, the other in Georgia, nor that he was a featured attraction in Johnny Jenkins’s band. Or that he earned $1.25 an hour as a water-well driller, and was fired from his job as a hospital orderly for singing in the hallway. That day, to those people, he was Jenkins’s valet. (Another fact not then known about Otis was that he was under contract to an enterprising producer and former used-car salesman in his hometown. That did not stymie Galkin. He snowed the snowman, tough-talking him that Otis wasn’t twenty-one when he signed—despite the fact that, when recording at Stax, he was still a month shy of his twenty-first birthday.)

By Thursday the sixteenth, Stax had Otis under contract, assigning him to the Volt subsidiary label. While some were excited by the new signing, Jim felt more a sense of obligation than exuberance; as far as he was concerned, the deal was really about Joe Galkin, not Otis Redding. “The black radio stations were getting out of that black country sound,” he says. “We put it out to appease and please Joe.” When the single came out, three months had passed and it was bundled with two other releases, one by Carla Thomas (“I’ll Bring It Home to You,” an answer record to Sam Cooke’s recently released “Bring It on Home to Me”) and another by the Mar-Keys (their version of Cannonball Adderley’s “Sack O’Woe”). These releases had the contemporary sound and feel, not Otis’s. His A-side was “Hey Hey Baby,” which sounded like a Little Richard imitation; “These Arms,” spare and “country” sounding, was buried on the back.

The world seemed to agree with Jim Stewart—Little Richard was the best Little Richard, and Otis’s record was going nowhere. A couple more months passed, and then the influential Nashville DJ John R., no doubt influenced by Galkin, flipped over the record. John R. broadcast on WLAC, one of the first stations to adopt “clear-channel” technology, meaning that at night its fifty thousand watts reached twenty-eight states. The station’s influence increased as radios proliferated, especially with the introduction of the transistor radio in late 1954. John R. broadcast when kids were going to bed, their radios tucked up under their covers. On his show After Hours, he serenaded them—America’s future songwriters—with hepcat talk and very un-lullaby-like rhythm and blues. John R. called to tell Jim he was promoting the wrong side and that the ballad was a smash. As pleased as Jim was to hear it, he was looking at months of little response. Figuring that something was worth more than nothing, Jim passed to John R. his portion of the publishing monies he’d gotten from Galkin. (The Federal Communications Commission would soon curtail such practices.) The gift had potential value; if John R. made it a hit, he’d get half a 1963 penny for every record that was sold. This, Jim had learned, was how records got played.

John R. set about playing the record every night of his show.

![]()

At Stax, it was a period of comings and goings. Two weeks after Otis came through and weeks before “These Arms of Mine” was released, Booker T. Jones—namesake for Stax’s biggest act, rising star of the house band, and recent high school graduate—left Memphis altogether to attend Indiana University, four hundred miles away. He’d been saving since folding newspapers outside Phineas Newborn’s house. With $900, he had enough for out-of-state tuition, and off he went. “I never thought, What am I doing going to college?” he says. “Lots of other people did. But it meant everything to my family for me to have a degree. My father was a high school teacher. He had a degree. His father had graduated from Mississippi Industrial College in the late 1800s and was able to purchase seventy acres of land in Marshall County, Mississippi, on which he built a school and became a teacher.”

As Booker settled into his freshman year, “Green Onions” was climbing to number three on the pop charts, overtaking Elvis Presley’s “She’s Not You.” But Booker didn’t give it a second thought. “Indiana changed my life. The standards they have—I don’t think I had any respect for regimen before I went there. And I was finally learning about all this music I was hearing in my head and playing—what it meant and how it translated and how to translate it to other people. How to write strings, how to write horns, what were the origins of this scale, how to conduct an orchestra—I found these things out at Indiana. I always heard music in my mind but I didn’t have the ability to translate so much of that music to the outside world.”

Though Indiana had an applied music degree, Booker pursued a broader education, studying business, art, and history. “Music gives you a way to organize not only notes, but all sorts of ideas. You think of twelve notes in the scale, and twelve colors in the spectrum, twelve months in the year, and twelve bars in blues. That’s Western music, but what about Eastern music? What if you have sixteen bars, or thirteen? Thirteen is the magic number if you use it in conjunction with eight and five. And that’s the golden ratio.” He smiles. “There are so many possibilities to link music with mathematics and beauty, with nature and art.” He soon received a $5,000 check from Stax for “Green Onions,” paying his upcoming tuition, and making a down payment on a Ford Galaxie 500 convertible. “I was styling. I went back to Memphis as often as I could and played sessions.”

No one fully appreciated the space that this quiet musician filled until he was gone. “Booker wanted to continue with his education,” says Steve. “How can you deny a guy that?” The studio knew they’d need a piano player, and saxophonist Floyd Newman, once again, was the linchpin: He brought Steve to his gig, at a South Memphis nightclub, to check out his keyboardist. “I heard a couple sets,” Steve says, “and I talked to the guy, asked if he’d be willing to do some sessions at Stax. And he says, ‘Oh, man, that would be great.’ So I told Jim, ‘I think I found us a piano player.’”

The young man’s name was Isaac Lee Hayes. He was working days at a meatpacking plant (“Hogs and cows being slaughtered,” Hayes says, “I couldn’t hardly sleep, but it was a living”), and he’d already been rejected by Stax twice, first auditioning with a blues band, then with a rock group. “Nobody would hire Isaac,” says Floyd. “Isaac used to hang around the studio and he would hear things that were beyond his knowledge. He was just a natural, but he wasn’t a very advanced player. When I hired Isaac, he could only play piano with one hand.” He’d since learned a thing or two, and Jim called Floyd to see if he’d endorse the idea. “I said yes,” Floyd remembers, “because you could drop a fork or spoon or plate on the floor, and Isaac would tell you what note it was. He was hearing everything.”

Isaac’s budding talent found fertile ground at Stax. He’d had no formal training on the keyboards—“I feel so limited, so restricted,” he says even years after he’d become a superstar. “It’s in my head, but I can’t get it to my hands.” But he was innately musical, with a strong sense of a song’s arrangement: He knew when to play, and when not to play. That endeared him to the musicians in the studio.

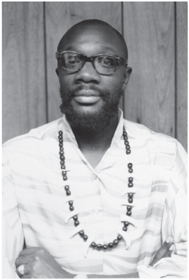

Isaac Hayes, songwriter. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

His first session was for one of Otis Redding’s early returns to Stax, after “These Arms” had hit but before Otis was anything like a star. “I was nervous,” says Isaac. “I was scared to death—they were gonna find me out, that I’m not good as Booker T. Jones. Well, Otis was a dynamic person. He was easy to work with. It was like a party whenever Otis came to town. We’d gather around the piano, work up the tune—the horn players, Al Jackson, Steve Cropper, David Porter did a lot of the backup singing—and I sat at the piano. After a few takes I just fell in line and it was like a big family.”

![]()

The family was growing. The woman who would develop and run the company’s publicity department, Deanie Parker, came through the door with her high school singing group that won first prize in a local contest: a chance to audition for Jim Stewart. “Mr. Stewart indicated that he was impressed,” says the petite chanteuse who’d moved to Memphis from Ohio a couple years earlier, “and then he asked a question that I had never heard before: ‘Do you have any original music?’” Deanie returned to her bedroom, dominated by an upright piano, and wrote lyrics, a melody, and taught the group. “And Jim was even more impressed. And then he said, ‘What are you gonna put on the B-side?’” She laughs, “‘B-side? What is a B-side?’” Her song “My Imaginary Guy” came out in February 1963 (with her “Until You Return” on the flip), as Otis’s “These Arms” was finding its audience. A playful song, it reaches back to the fifties for a mambo beat, with rich backing vocals; it also calls to mind Carla’s “Gee Whiz,” with its dreamy, youthful melody. It makes you reach for your ink pen and school notebook to doodle.

Deanie hit the road with her musical ensemble—and the road hit right back. “These artists were leaving their homes to go on the road,” she explains, “where they did not have hotels where they could rest, did not have restaurants where they could eat. At any given time, a sheriff might appear out of a cotton field and stop you just for the sport of stopping you, tell you that you were speeding when you know that you were driving under the speed limit. As an African-American, you knew that any excuse and no excuse was good enough to be stopped, and humiliated, or treated as a second-class citizen. I didn’t have the soulfulness of Aretha Franklin, I could never belt out a song like Gladys Knight, and I certainly didn’t have Tina Turner’s legs. So, I thought I needed to find something else to do.”

Deanie pursued her college education and found a part-time job. “Estelle Axton hired me to be a salesperson at the Satellite Record Shop. And she asked me for recommendations for other salespeople, so my popularity soared.” Others, too, were taken by her spunk and charm. “Jim Stewart made me the first publicist for Stax Records, even though I had no experience. We contracted the services of Al Abrams, who had done marketing, PR, and publicity for Motown. He really, by mail and by phone, taught me how to structure a press release, how to pursue the media, how to prepare the artist for the interview—fundamental things.” In 1964, Deanie Parker would become the company’s first salaried African-American office employee.

![]()

In the fall of 1963, Stax released a record that would rival the success of “Green Onions.” Since giving the company its first hit, Rufus Thomas was proving himself an endless source of song and fun. He followed “The Dog” from earlier in the year with a sequel that was promptly covered by the Rolling Stones on their debut album and has been often imitated, but never equaled.

There was a certain happenstance to the recording of the song, extending from Jerry Wexler’s New York restiveness. He’d been expecting a new song from Carla Thomas for several weeks, and every time he’d phone Jim, Jim reported that the equipment was broken. Wexler turned to Tom Dowd, trained as a nuclear physicist and working as Atlantic Records’ chief engineer. “Jerry was thinking they were up to something down there so he called me in, said, ‘Dowd, you’re going to Memphis tonight.’ He said, ‘There’s no equipment in life that’s gonna be broken for two weeks, so find out what are they doing.’ Okay, fine. Jim Stewart picked me up at the airport on a Friday evening, took me right to the studio, and I saw there was a brake band broken, a few normal malfunctions on a machine. Jim said, ‘We can’t find the parts.’ So I called my engineer in New York, said, ‘You bust into Harvey Radio first thing in the morning, get me a pair of brake bands for a 350, get me a couple 65K resistors, get me two capacitors, an on-off switch, and then go straight to the airport, give a stewardess on the first plane to Memphis twenty-five dollars to carry them, and I’ll meet her.’

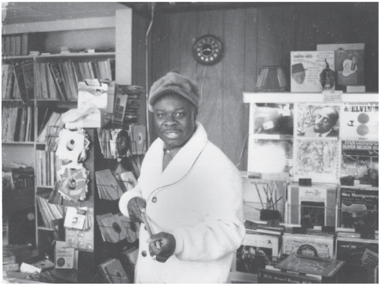

Rufus Thomas in Estelle’s Satellite Record Shop, early 1960s. (Photograph by Don Nix/Courtesy of the Oklahoma Museum of Popular Culture, Steve Todoroff Collection)

“Next morning I asked Jim to take me to the airport to pick up the parts. I think he was a little taken aback. But we returned to the studio, I plugged in a soldering iron, boom boom boom, had the machine running in about thirty-five or forty minutes, said, ‘Okay, we’re ready to record.’” Dowd couldn’t get a flight out until late Sunday afternoon, and arrangements were made to play golf on Sunday morning with some of the guys. Dowd was about to confirm yet again that Memphis is the town where nothing ever happens, but the impossible always does. “We played ten or eleven holes and all of a sudden Steve says, ‘Well, we’d better be heading back to the studio, we just about have time to get coffee and doughnuts.’ And I was surprised because it was Sunday. Well, on Sunday when people come out of church, they fall by the studio. Al Jackson shows up and Isaac [Hayes] and David [Porter] and the horns mosey in. We’re talking and they were asking me questions and playing me things. Then Rufus Thomas comes walking in the door and says, ‘Hi everybody!’ He says, ‘Everything workin’?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, it’s working now.’ And Rufus says, ‘I got a song!’ So Rufus runs this song by them once or twice, and I’m up in the control room to engineer and I’m laughing. Steve looks up and says, ‘You ready to record?’ And I say, ‘You got it, let’s go!’ Boom, right? Rufus never broke stride. He sang it for the band twice, says, ‘See y’all later!’ and he walked back out the door, going home to have Sunday dinner. It was very casual.” The Stax folk listened to the playback and were in awe of Dowd’s work. Through experience and science, he knew how to capture the most life and make it stick to the tape. Jim said it was the best-sounding record yet to come off their console. Dowd continues, “It was pleasant people enjoying each other’s company and having good conversation. And I had under my arm when I went back to New York, I had ‘Walking the Dog.’”

For Dowd, Stax had been a walk through the looking glass. In New York, sessions were by the union book, with the clock ticking off three hours and the pressure always on. Sessions proceeded in proscribed ways: Music was put on charts by the arranger, which the musicians played according to the instructions of the producer. Certain people worked in the control room, others on the studio floor, and they communicated on microphones through the glass, with neither invading the other’s space. Not in Memphis. It was a revelation to see the free passage between the control room and the studio floor. Everyone was welcome everywhere. It was a fluid environment, even with the song arrangements. No musician’s parts were written, nothing was worked out in advance. For “Walking the Dog,” Rufus hummed his ideas to the players, they improvised. He dictated the rhythm by getting close to the player’s ear and clacking his teeth. It worked. The song is extra funky, a tight, bouncing stroll down a young and sunny street. Steve’s guitar leads the parade, loose like a rubber band. Every bend he ever played, he made his own. Packy’s saxophone grins its way through a verse. (“Packy was not the greatest saxophone player in the world,” says Duck, “but he had the heart of the greatest saxophone player in the world.”) Musical charts would have been less useful than racing charts. “Head charts,” they called this—making it up and using the good parts.

Packy Axton, left, and Don Nix. (Photograph by Don Nix/Courtesy of the Oklahoma Museum of Popular Culture, Steve Todoroff Collection)

In New York, Wexler was more amazed by the process than the song—and he loved the song; soon he’d visit Memphis to produce there himself. “Memphis was a real departure,” he told author Peter Guralnick, “because Memphis was a return to head arrangements, to the set rhythm section, away from the arranger. It was a reversion to the symbiosis between the producer and the rhythm section. It was really something new.”

It was also really something old. The studio maintained a mono machine and a mono sensibility well past the advent of stereo, when two tracks of playback enhanced the sound’s dimension. Not a company to lead the technological charge, Stax captured what the others couldn’t—spirit. Jim had no reason to argue with what was working. But Tom Dowd did. “When I came down here, 1962, I was appalled. These people were still recording on a machine like I abandoned in 1952. And when I said, ‘We should replace this machine with a new two-track machine,’ it was an appalling suggestion. They thought their sound was gonna be destroyed if they went into this.”

Dowd was motivated by more than technology. Albums manufactured in stereo sold for a higher price, garnering more profits. It would be the summer of 1965 before he connected a stereo machine to the front of the mono machine, allowing Stax to work, as was their custom, in mono, but simultaneously producing a stereo tape. “I said, ‘You just listen on the one speaker in mono and whenever you send me a tape, send it to me off of this stereo machine. You make it sound good in mono, I’ll worry about the stereo.’” Stax got comfortable with stereo, and in 1966, Dowd would install a four-track recorder. More tracks expanded the possibilities for overdubbing and mixing. For the players, more tracks meant that when one person messed up, not everyone had to redo their parts. More peak performances could be kept.

![]()

Stax was becoming a company of national renown, but in its South Memphis neighborhood, it was the rising home team for which everyone root-root-rooted. For those African-Americans who had recently ascended to the middle-class neighborhood, Stax was a validation. Neighbors could insert themselves into the success: My record clerk was a recording star, a songwriter, a tastemaker.

The democracy—the opportunities—of the studio was already legend. Rufus and Carla walked in the front door, danced onto the national charts. High school kids were leading bands—with songs on the national charts. The dang driver from Georgia who walked in carrying amps recorded his own song there—and was rising again and again on the national charts. Still, it was an unreliable way to run a business.

As the legend spread, more unknowns would enter, expecting to get heard. But with the studio growing, more sessions were going on, leaving less time to cater to the individual potential legends. Since the musicians worked late on weekend nights, the studio was quiet earlier in the day. “We just told people to come back on Saturday morning, and starting about nine until noon or so, I got to hear a lot of stuff,” Steve says. “I don’t recall any superstars coming out of that, but it kept things flowing.” These Saturday-morning auditions became a weekly conduit between the neighborhood and the studio. Sometimes it was a duo, a man playing solemnly at the piano, harmonizing with the woman standing stiffly beside him. Sometimes a lone white guy, strumming country guitar and crooning; or four guys from the street corner harmonizing like pros, in amateurs’ outfits that paid homage to the day’s natty dressers. Most had never seen the inside of a studio before.

“If you had talent—if you thought you had talent—you could go there,” says Rufus, his racial wariness eased in this sanctuary. “Nobody else was doing that around here. No studios—no nothing—ever gave any of the black artists that kind of a chance.”

Elsewhere in Memphis, blacks stepped to the curb when whites walked by. The city closed its public swimming pools rather than integrate them. And in June 1963, over one hundred sanitation workers came to a meeting called by organizer T.O. Jones, an effort to solidify the group’s complaints. The city, however, sent informants, and less than two weeks later, thirty-three men who’d attended the meeting—including T.O. Jones—were fired. Jones spent months fighting to get those jobs back, and was mostly successful, though he chose not to return to the daily humiliation and instead devoted himself entirely to forming a union. He soon had reason to be optimistic: The intransigent Mayor Loeb resigned in October after a death in his family, and an African-American community banded together to elect a moderate, Judge William Ingram, who had distinguished himself on the bench as a voice for the common man, publicly rebuking the police force for unlawful tactics. The community also supported a new Public Works commissioner, Pete Sisson, though he turned on them shortly after being sworn in, stating in early January 1964, “I do not expect, nor will I tolerate, agitation within my department. I receive applications daily from too many prospective employees who are ready and willing to go to work immediately to allow discord within the ranks of this department.” When Mayor Ingram did not come to the sanitation men’s rescue, the new optimism quickly dimmed.

T.O. Jones organized the sanitation workers and fought for union representation. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

At Stax, everyone had a chance. One neighborhood group in their early teens became reliable assistants to the studio regulars (valet was the fancy term used), and as they learned to play, they would soon form their own group, the Bar-Kays. “I used to get my hair cut up there next to Stax when I was a kid,” says James Alexander, who was born in the clinic (925 E. McLemore) across the street from Stax. “Carl Cunningham was the first one who started getting into Stax because he shined Al Jackson’s shoes at the barbershop and he aspired to be a drummer. Al used to let him sneak in and get on the drums. I wanted to get in there too. Al, Isaac and David, Booker T.—they took us under their wing. When there were no sessions, we’d start beating on the instruments and when they saw we wasn’t gonna leave, we became part of the family. Otis Redding, soon Sam and Dave, and all these people, they always needed stuff done—clothes to the cleaners, cars need washing, shoes need shining. We were like little puppies running around in the studio.”

“The Bar-Kays used to come in there and just sit and listen to us the whole time we’d be recording,” says bassist Lewie Steinberg. “They sat, listened, and learned from us.”

“We were playing the songs that you hear on the R&B radio stations,” continues future Bar-Kay James Alexander. “We would play Brook Benton. We learned to play the Stax stuff that was getting popular, ‘The Dog’ by Rufus Thomas, things like that. Monkey see, monkey do—wasn’t no such thing at that point as trying to play originals. We would just learn the songs off the radio and play them.”

They’d gather around the record player in Estelle’s shop to deepen their understanding of the songs. Despite all the studio-centric work that went on in the store, records did get sold. Business got so good that Estelle expanded into her own place, taking the front of the bay next door when the barbershop folded.

The Bar-Kays came into their own at Booker T. Washington High School, a few years after Booker T. Jones, William Bell, and William Brown graduated from there. Booker T. was the African-American public school on the south side of town (a mile from Stax), and it had a large auditorium. It often hosted major events, one of the largest being a talent show that since the 1940s had been known as the Ballet. It was the premier showcase for up-and-coming talent, rivaling the Palace Theater’s Amateur Night, which in earlier years had sprung Rufus Thomas, B.B. King, Bobby Bland, and many others. “The thing during those days was to get your talent good enough to be on the Ballet,” says James. “We played that night and I’ll never forget it. We got suits from Lansky Brothers on Beale Street, maroon shiny suits, pink shirts, black patent-leather shoes, and we had—you had to have—black silk socks. We had a pretty hot horn section and we always liked to move around onstage. We played ‘Philly Dog’ by the Mar-Keys, and that really brought the house down.”

These kids paid tribute to the rising national stars who had graced the same stage not long back. The 45s by the recent graduates from Booker T. Washington were in every record collection alongside James Brown, Brook Benton, and Etta James.

![]()

One of Stax’s biggest fans left town in 1963. Local disc jockey Al Bell was offered a job in the Washington, DC, radio market, where his swinging sophistication quickly became popular on drive time, mornings and evenings. “Al Bell would come by the record shop,” remembers Steve Cropper, “and he’d invite us to the station. We got to be friends. I was allowed to bring him and other DJs brand-new product and demos, and if they liked it, they actually put it right out on the air. Didn’t need anyone’s permission, just played it. And the day that Al Bell went to Washington, DC, I lost a buddy. He was such a part of us—he’d hang out at the record shop, helped write songs with us, played our records—and when he left, we lost a big part of the whole thing that Stax was into.”

Bell made the most of his outsider status, bringing the sounds of southern soul to this North-South border, introducing Otis, the MG’s, Carla, and all the talent from Stax, Fame, Hi, and the myriad of southern labels to a new audience. He would soon use Otis’s 1964 recording “I Want to Thank You,” the flip side of his “Security” single, as his sign-off song. When the sound found favor in DC, DJs elsewhere on the East Coast could justify playing the music.

No one at the time could know, but Al’s foray on the East Coast would prove propitious in just a few years’ time.