Jim Stewart had never taken a producer’s credit for his work at Stax. There wasn’t much room on a single to designate a producer, and when albums came out, his credit read, SUPERVISION: JIM STEWART. Many times he had produced, and many times he’d stayed out of the way, knowing when these talented kids didn’t need his input. He usually engineered the recording, and if things moved in a direction he didn’t like, he’d make it known. Part of Stax’s success was based on everyone contributing ideas. “There was a lot of creativity in those days,” says Jim. “Total involvement from everybody. There was no greed factor, and no limits to the input that we gave.”

Early in 1966, Isaac Hayes and David Porter were working on material for an upcoming Sam and Dave session. Isaac and David had become Stax’s custodians of Sam and Dave, writing and producing nearly all of their material. The two sets of partners fed off each other, the ideas between the four providing inspiration and vigor.

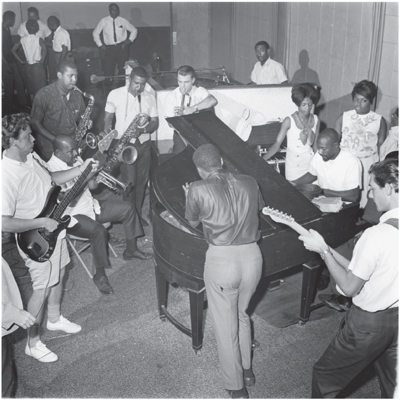

Sam and Dave weren’t harmonizers, they were combatants, each vocal line a thrust and parry, goosing the other to reach further, jump higher, and dance harder. In the studio, David coached the vocalists while Isaac arranged the band. David pushed them higher in their registers—it was a harder reach, and he liked hearing that extra effort in their voices. “There was not a musical chart there,” says Sam, who had previously worked with bands that read their parts off charts written before the session. “Isaac would voice that stuff with the piano. ‘This is what I want the horns to do, this is what Sam and Dave’s gonna do—’ He would voice everything. I would go, ‘God, this guy!’—’cause I’m not accustomed to seeing that.”

L–R: Jim Stewart (partial), Duck Dunn (shorts), Gene “Bowlegs” Miller (seated), Andrew Love, Floyd Newman, Wayne Jackson, Eddie Floyd’s back, Al Jackson (drums, rear), unidentified background, Isaac Hayes (piano), Mildred Pratcher Steve Cropper. (Promotional photo by API Photographers/Earlie Biles Collection)

“Sometimes David and I would sleep all night under the piano,” says Isaac, “and we’d be awakened the next morning by the secretary. ‘What are you doing here?’” There were other places Isaac preferred to sleep, and this night, working late in preparation for Sam and Dave, Isaac, a ladies’ man, had a date waiting—at home, for him. But he and David were committed to their responsibilities and knew that most songs are not born without labor, and ideas have to be nurtured until the heart is revealed and the body can be built around it. It was late, no one else was in the building, and David, pacing the studio, retired for a bathroom respite. He walked up the sloped floor, went through the old theater doors, and was sitting on the toilet, listening to Isaac noodle on the piano. Inspiration can be elusive, the ideas being—as the term indicates—breathed into a person. And as Isaac moved his hands on the black and whites, David’s ears perked up. He could hear form taking shape.

“I finally struck a groove,” says Isaac, “and it’s taking David forever! I said, ‘David! C’mon man, I got something.’”

David had heard Isaac’s progress, but he had his own business to finish. He hollered back from the stall, “Hold on, I’m coming.”

Isaac continued with the chords, but in a moment his concentration was broken by a commotion from the back of the room. “That’s it! That’s it!” David ran in yelling, one hand holding his pants halfway up, the other one waving wildly. “Hold on, I’m coming! That’s it!” It would be the chorus, and title, to Sam and Dave’s breakout song.

They developed a basic structure, and Isaac had a horn riff he’d put on tape a couple weeks earlier, an idea too good not to have on hand. He’d called together the horn section so he wouldn’t forget it. He pulled the tape and it fit their new song, heroic like the cavalry’s arrival. At the next day’s session, they built the parts quickly. For the rhythm David referenced the funky hit out of New Orleans, Lee Dorsey’s “Get Out of My Life Woman.” That proved a good starting point for Al Jackson. Isaac’s horn part became a central riff. Steve dug into his James Brown trick bag for a funky guitar part, and the result was a surefire hit that shot up the R&B charts all the way to the number-one position. Penned as a love song, this piece transcends romance and becomes a cultural message with civil rights overtones, urging unity among African-Americans, reminding that help is always nearby—and on the way:

Don’t you ever, be sad

Lean on me, when times are bad

When the day comes, and you’re down

In a river of trouble, and about to drown

Hold on, I’m coming

Hold on, I’m coming

“That was the chemistry,” says Sam. “Sam and Dave, Hayes and Porter. Just like the chemistry between Berry Gordy and Motown and between Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones. Hayes—I believed in whatever he said. His mouth, to me, was a bible.”

“Isaac would be playing piano,” says Duck, “and David would be behind the [sound] screen, almost like a band director. He’d tell them which line to sing when. David was great with that.”

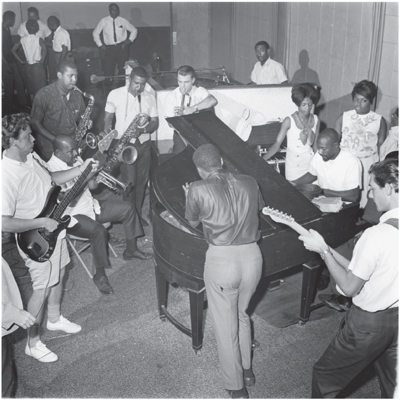

Listening to a Sam and Dave playback in the control room. The Altec Voice of the Theater mono speaker is to the right. L–R: Sam Moore, Isaac Hayes, Andrew Love, Wayne Jackson, Dave Prater, Jim Stewart, Steve Cropper. (Promotional photo by API Photographers/Earlie Biles Collection)

“When it came to laying down the vocals,” David Porter told the Smithsonian Institution, “I’m on one side of the mike, Sam and Dave are on the other, and I’d direct them, like a choir. One hand: you hold it, you do the ad-lib. Take the hand up: you do the ad-lib up high. Take the hand down: ad-lib lower. Laying down the vocals was orchestrated and developed at the mike.”

“Porter was tough—oh, he was tough,” says Sam. “He wanted hit records. And I’m lazy, I’m the first to admit that I’m very lazy. I don’t want to sing all up in the ceiling—I visualize being Frank Sinatra, or Nat King Cole, Sam Cooke. And he would change keys on me. He challenged me a lot.” Sam got sound advice from Jim Stewart as well. “‘You’re trying to compete with Motown,’ he told me. ‘Stop. Motown’s vision is pop. You are raw soul. Let’s concentrate on that.’”

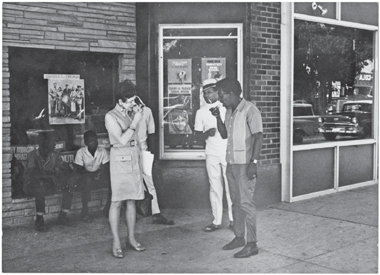

Sam, with some exceptions, did not like the songs they were being given at Stax—even after they started hitting. He still heard himself as a crooner and balladeer. And when he was feeling down about the material, he’d voice his concerns where everyone at Stax went to disburden themselves: the Satellite Record Shop counter. “Estelle—it was her money that started the company, and she always stood up behind the counter at Satellite. I’d say, ‘Miz Axton, I don’t like that song.’ She’d say, ‘Sam, you and Dave stick with it son, that’s a good song.’ I’d go back in the studio, I’d focus on what she’d say. Goddogit if it didn’t work out like she said.”

“Hold On” was released mid-March, 1966, and it was the kind of powerful, catchy, and exciting song that made Al Bell’s promotion job both more exciting and more difficult—giving him that many new disc jockeys to reach out to. Three weeks later, it hit the R&B charts, where it would stay for twenty weeks, working its way to number one in mid-June; it peaked at number twenty-one on the pop charts at the same time, a song of the summer. They got better TV appearances, broke into wider—and wealthier—audiences. Sam and Dave were becoming mainstream artists.

This expanded fan base—the dreamed-of crossover success—was further evidenced by sales of their first album recorded at Stax. Where most of the market had been singles so far, Al Bell saw not only the growing commercial trend toward albums, but also the higher profitability in their sale; they were more expensive to create and produce, but their higher price allowed a significant profit margin. Riding on the back of their hit single, their album Hold On I’m Coming proved to be the breakthrough for Stax’s album sales. In all the company’s years through 1965, they’d released only eight albums—on the Stax and Volt labels combined. After Al Bell arrived, in 1966 alone they released eleven albums, and Sam and Dave’s Hold On went to number one on the R&B album sales chart.

Estelle Axton outside the Satellite Record Shop. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music/Photograph by Jonas Bernholm)

Albums were good business, as Al would demonstrate over the years to come. “The albums were generating more revenue than the singles,” he explains. “There were times when we’d sell a hundred thousand albums, and at the end of the year, that adds up to serious cash flow. If they were retailing at $6.98, then our wholesale was three and a half dollars or so per unit. So one hundred thousand units is three hundred and fifty thousand dollars. We were generating cash. We had obligations with writers, producers, and publishers, and our fixed costs, and general administrative expenses. But we had the gross revenue coming in, because we had hit records.”

Beyond his promotional abilities, Al was becoming a dynamic personality within the company. When the MG’s became frustrated with Jim, Al would step in; Jim’s stoic pursuit for perfection drove even his most loyal employees to irritation. Sam and Dave leaned on Al in the same way. “Jim recorded almost all of our hits, but Jim and I had our differences,” says Sam. “I had a big mouth. Jim had no personality. He depended on Steve Cropper. I’m saying, ‘Steve Cropper’s mouth ain’t no damn prayer book.’ I was called on the carpet to keep my mouth shut. And Al became the man between Jim and myself. Al Bell became a spiritual adviser. One time we were supposed to perform in Atlanta for the National Association of Television and Radio Announcers. I was upset with Jim Stewart and Al talked to me, said, ‘You can be upset, but don’t take it out on the people in Atlanta.’ Stax did a good job promoting. And over the years, Jim and I turned out to be good friends. His sister—there was nothing I wouldn’t do for her.”

![]()

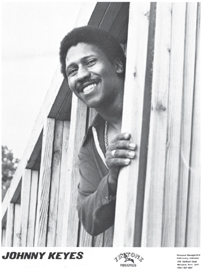

The family feeling still dominated, but in the solidifying hierarchy, there was no place for Packy. In the wake of the “Hole in the Wall” success, the Magnificent Montague, the LA DJ and promoter, matched Packy with Johnny Keyes, a vocalist, conga player, songwriter, and laid-back African-American hipster from Chicago. They formed a band and a deep friendship, and the Packers toured behind the single, ultimately winding down in Memphis. There, any friend of Packy’s was instantly adored by Estelle, so Johnny found himself with a job at the record store, and a new mentor—Estelle—who was paying for an apartment he shared with Packy near Stax. “Packy would go home every now and then, but he preferred to stay in South Memphis with black people,” Johnny says. “She didn’t fight it. And she believed in me and my talent. She’d say, ‘Johnny, when you write something, look through a magazine and you’ll come across some phrases you might be able to use.’ She said, ‘I’ve found that records sell when you ask a question. Will you still love me tomorrow?’ I said, ‘Ahh.’”

Johnny Keyes, who became Packy Axton’s best friend. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

Johnny wrote songs for Stax’s East/Memphis publishing. He and Packy cowrote “Double Up” with Estelle’s employee Homer Banks, and it had an appeal to Sam and Dave who, in a recording frenzy, were working on their second album of 1966; they wanted to call it Double Dynamite, so Johnny’s song had thematic appeal. “Miz Axton had told us, ‘If you give them that tune without getting publishing, I’m through with both of you,” says Johnny. “She said, ‘I’ll stop paying your rent, I won’t back you in anything you do, you’ll no longer be able to borrow money from my cash register.’ She said all bets would be off. David Porter said, ‘We’re gonna cut it and we’ll start rehearsing the tune.’ I told him we needed to have half of the publishing and he said he’d talk to Jim Stewart.

“So Sam and Dave are rehearsing ‘Double Up,’ I’m elated. David comes back and said, ‘We don’t split publishing.’ I said, ‘Yes you do, East Publishing splits with Otis’s publishing company, Redwal.’ He said, ‘No publishing, but we’ll make it a single from the album.’ That would have boosted our money as writers. But then I could hear Miz Axton’s voice in my ear—‘All bets are off if you don’t get the publishing.’ I held my ground. All of a sudden they said, ‘Stop rehearsing the song, the deal is off.’” Sam and Dave had to abandon the song, but Estelle didn’t leave Johnny in a lurch. She had him teach the song to Clarence “C.L. Blast” Lewis, a solid Memphis soul singer. She booked time at Ardent Studios, an up-and-coming facility in town (they’d installed the same recording console as Stax, with an eye toward getting their overflow work). C.L.’s “Double Up” came out on Stax and didn’t chart, but Keyes and Axton still had their rent paid.

![]()

Though Stax had all these records on the charts, they were still a provincial company. Songs may have been played in the Northeast, Midwest, and down South, but the Stax personnel recorded them in Memphis, mailed them out from Memphis, and read about them while they sat in their Memphis office. So when the phone rang in the spring of 1966 and the crackly voice on the other end said it was England calling, they wondered if it was a joke. Their credulity was further tested when the caller identified himself as Brian Epstein, manager of the Beatles. He’d gotten their phone number from Jerry Wexler. The Beatles would be touring the US that year and, as their December 1965 album Rubber Soul indicated, they were grooving to the sounds of sweet southern soul. (The song “Drive My Car” lifted the bass line from Otis’s “Respect.” “That’s my one la-di-da,” says the ever-humble Duck Dunn.) The Beatles were at new heights of popularity, and bursting creatively, working toward their Sgt. Pepper breakthrough the following year.

In March of 1966, the Beatles’ manager was in Memphis, surveying the landscape, with Estelle as his host. She placed him in the luxury downtown hotel, the Rivermont, and suggested the Beatles could stay there too; touring politicos were often put up there. (Elvis, meanwhile, offered Graceland.) Estelle’s son-in-law worked for the Memphis police, and his responsibilities included traffic detail, so she assured Epstein that the Beatles would have no trouble moving through town. A plan was developing.

“One day Miz Axton came to us,” says Johnny Keyes, “and she said, ‘Don’t spread this around, but the Beatles are coming to Memphis.’ Everybody told somebody, ‘The Beatles are coming, don’t tell anybody.’ And soon everybody knew.” Johnny remembers girls coming into the record shop, and hysterical, offering money for information, trying to buy the dress the secretary would wear when the Beatles came through the door. “It was wild, man,” he says. “Nobody knew, but everybody did.”

“They wanted to record at Stax so bad,” says Don Nix, who later befriended George Harrison. “They had the whole thing all laid out, were gonna land a helicopter on the roof. But word leaked out.”

On the front page of the March 31 morning newspaper, just below the article KLANSMAN CHIEF TO GIVE SELF UP, is the headline BEATLES TO RECORD HERE. In the article, Brian Epstein’s visit is acknowledged, and Estelle announces their April 9 arrival, explaining they were drawn by the sounds of Otis, Carla, Rufus, the MG’s, and others. She confirms an album and a single are planned—Jim will produce, Steve will arrange, and Tom Dowd will come down from Atlantic to supervise. The Beatles, yes, but the newspaper realized that readers may not be familiar with the studio that has drawn their attention. So the article ends with an explanation for the general public who, familiar with the Beatles, may not know this world-renowned studio in their hometown: that “has had unusual success with Negro artists.”

Once fans had official confirmation of where to be on what day, the Beatles had to cancel; Beatlemania was still in full swing. The album Revolver would be recorded in London, and its songs are full of soul possibility. The horns and vocal style on “Got to Get You into My Life” are the most obvious paean to the American soul sound, but the dark funk of “Taxman” and the bright punch of “Good Day Sunshine” would also have been right at home in Memphis.

The Beatles had not called Motown in Detroit, and while the African-American label in the North continued to dominate Stax in sales, it did not dominate in soul. The Beatles canceled, but artists from Elton John to Janis Joplin and the Monkees all came through. Stax was setting the bar for grit and feeling in commercial music.

![]()

Even by 1966, it was difficult for an integrated group to drink a cup of coffee in public, much less dine formally or casually in Memphis. Usually, establishments that catered to African-Americans were more welcoming to mixed groups and to visiting whites. The Lorraine Motel’s small restaurant and swimming pool were always hospitable, the prices were reasonable, and that was where Stax would usually host its guests. “When I’d come to Memphis, I stayed at the Lorraine,” says Eddie Floyd. “And that’s where we would write songs. Mr. Bailey, who owned the motel, he didn’t care about the noise and he liked having us around.”

“Anytime you went to the Lorraine,” remembers Mavis Staples, who traveled often through the South with her gospel-singing family, the Staple Singers, “it was like a reunion. Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland, Little Junior Parker, Joe Hinton—everyone stayed at the Lorraine Motel. Mr. Bailey and his wife and daughter [the motel was named for the daughter] had a nice restaurant there, and it was just the motel for blacks in Memphis. That was home away from home.”

“We used their dining room for our meeting hall and we swam in their pool,” says Booker T. Jones. “We ate there on a regular basis. The Lorraine Motel was an institution for us.”

Eddie Floyd (Photograph by API Photographers/API Collection)

“When I was writing songs with Eddie Floyd,” says Steve, “Mr. Bailey would give us the honeymoon suite if he didn’t have it booked. It was plush red velvet everywhere, a big room, and it was great.”

Eddie’s “Knock on Wood” was written at the Lorraine. “Steve and I were trying to write a track for Otis Redding,” says Eddie. “We’re sitting at the Lorraine in the summer. It’s storming, there’s lightning, and we’re trying to come up with a song. Steve’s strumming, and I had an idea for a line: knock on wood. Steve had the idea about the rabbit foot for good luck, and stepping over those cracks in the sidewalk, black cats, all that. Then I told him the story of when I was a kid in Montgomery, Alabama, when it was storming big like that, thunder and lightning, we used to hide under the bed, and we’d be frightened. He said, ‘That’s it, that’s it!’”

“Wayne Jackson was playing in West Memphis, and I called him on a break,” says Steve, “said, ‘We’ve got a great song, when you get off your gig, come by the Lorraine and help me with the horn arrangements because I want to cut this tomorrow morning.’”

This wasn’t the first time Wayne had received such a call. “I’d go to the Lorraine, sit on the edge of the bed, and there Steve’d be with a guitar and a singer,” says Wayne. “I’d use a mute so that I wouldn’t wake people. I’d play the little horn lines that they were talking about, or try something else. We’d work until everybody was tired. I could remember the lines till the morning, and in the studio we’d have a song to show everybody.”

“The next morning,” says Steve, “we worked it up with the band. Hour or two later, we had it cut.”

Eddie credits Al Jackson with making the song a hit. “He said, ‘Let me put something in there.’” Eddie laughs. “And he put in a break where everyone stops and he hits the drum, like knocking on the door. Everybody laughed, but that’s what makes it. If he hadn’t did that, I’m convinced it wouldn’t have been a hit.”

“Knock on Wood” was cut as a demo for Otis Redding, but once done, it didn’t sound like Otis’s style. So Stax released it, and with Al Bell promoting it, Eddie’s demo hit the number-one spot on the R&B charts and became a top-forty pop hit.

![]()

Hits created a cash flow, with money for the songwriters and the label based on numbers of copies sold, and money for the artists based on radio play (and the reward of better-paying gigs). But the musicians who backed the artist were paid per session, union scale, whether the song hit or missed. (Often their pay was considerably less, what the union termed “demo scale”—fifteen dollars—with the remaining fifty to come if the song were actually released.) At studios in New York and Los Angeles, union rules stipulated that sessions were three hours and it was expected that four songs could be cut in that time. Musicians arrived, were given sheet music, and they played the part as written. At Stax, a song might be sketched out, as “Knock on Wood” was, or it might develop in the studio and need to be rehearsed over time. “We might spend a month working on four, five, six artists and records,” says Steve, “trying to get a hit single on them.” The pay wouldn’t come until the recording session did.

The studio stars kept their club dates because they needed regular income. When Steve phoned Wayne for help with “Knock on Wood,” Wayne was working a nightclub gig into the wee hours. He had a wife and kids at home. He was selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door in the daytime, catnapping in his car. Most of these musicians, cutting hit after hit after hit, were scrounging to make a living. Al Jackson was in the clubs at night. Booker, recently resettled in Memphis after college, was taking club gigs. And most of these players were feeding young families, too.

Duck Dunn, who was playing on all the hits, was still working days at King Records and nights at the Rebel Room or Hernando’s Hideaway, in addition to sessions—just to make ends meet. “I’d work till two in the morning on the bandstand,” says Duck, “then stop on the way home to see Al Jackson till four and then be at King Records at eight. My wife used to take a broom and poke me to wake me up. I went out and did Shindig! and I left [my wife] June and my son Jeff with fifty dollars. I’m doing Hollywood TV and we’re living off peanut butter, eating Kentucky Fried Chicken.”

Al Bell was increasingly aware of their struggles to make a living. He saw the yawning, the bags under the eyes. “Finally,” Duck continues, “Al Bell says, ‘We need to put these guys on salary.’ Man, it relieved me from working till two in the morning. That’s one reason I respect Al so much—he took me out of my nighttime job and made me a studio musician.”

After giving them $125 a week, Al took the incentives even further by spearheading the move to form a production pool, a pot of royalty money to be equally shared by the six key players responsible for most of the sessions and hits. With his track record of success, Al held some sway with Jim, and he convinced him of the benefits. “The MG’s became the group that backed everybody,” says Al. “Whether it was Albert King with his blues, or Carla Thomas with her pop, or William Bell—they adapted to whomever it was that came in the studio. And Isaac and David were doing most of the writing and lots of the producing.” Stax was being paid a royalty from Atlantic of about 15 percent, and Al arranged for a sliver of that money to be divided equally between the four MG’s and Hayes and Porter. “It was the fairest way to give them a producer’s revenue,” Al says. The more hits they made, the more these six core players would earn.

“Al made Booker T. & the MG’s and David and Isaac part of the company,” says Duck. “And what can I say? Here’s a gift that saved my life.”

The production pool resulted in a new distribution of duties, with each key player assuming responsibility for certain artists, and each being made a company vice president. Steve had Eddie and Otis. Al Jackson had Albert King and a few others; often he and Duck shared. Booker had William Bell, later Albert King—and there was fluidity within the designations. Thereafter, all the albums and many of the singles included a producer’s credit.

While generous, this also further compartmentalized a very collaborative organization. If one player were designated as producer, would the others feel as free to introduce suggestions? Or would that be stepping on toes? Or contributing with no reward? Suddenly there were proprietary concerns and a new layer of politics. “In my mind that was one of the things that began to break down the Stax structure,” says Booker. “I was vice president of something and I had an office. But I wasn’t feeling it.” No one was bemoaning the better money, but the new emphasis on individual profit introduced weeds into the garden.