Stax stood tall as a symbol of opportunity, a beacon in the neighborhood, the glow from the ascending stars ensconcing nearby residents. Deanie Parker, who had enlisted local kids into her Stax-Volt Fan Club, hired them for small change to help get mass mailings packed and ready. In the label’s conference room, they’d be stuffing envelopes, the excited chatter audible through much of the building. William Bell, Rufus Thomas, Carla—artists would stop in and encourage the kids, thank them for helping. And Stax’s light shone brighter.

There was one group of African-American teenagers who had penetrated the studio doors earlier, and gotten in deeper, than the others: the Bar-Kays. “Every spare chance we got,” says bassist James Alexander, “we’d go down to Stax to watch various people play.” After performing at Booker T. Washington High School, they got a nightclub gig across the Mississippi River in West Memphis—even though they weren’t old enough to be inside. They’d recently met the white keyboardist Ronnie Caldwell, also a high school student, and become an integrated band. “It was pretty unusual at that time to integrate,” James continues, “and the Bar-Kays and Booker T. & the MG’s were two of the first groups around here to do it.”

Originally named the Impalas after the car that got them to gigs, they rechristened themselves the Bar-Kays; it was inspired by a Bacardi Rum billboard with letters missing, and it evoked Stax’s Mar-Keys. They played Willie Mitchell’s hit “20-75,” Junior Walker’s “Shotgun,” and the funky, Latin-tinged “Watermelon Man.” They covered Ray Charles and even worked up a couple Beatles tunes, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and an original take on “Michelle.” “We wanted to be a band,” explains James, “but we wanted to act like a vocal group, doing steps like the Temptations.” They could back a vocalist or carry a set with just their instruments, their energy drawing the audience from their seats—a good time for the band, the dancers and listeners, and soon for the club owners. Sometimes, they’d get calls for sessions. Ben Cauley had recently played trumpet on Carla Thomas’s “B-A-B-Y” and several Rufus Thomas songs.

Signing the charter for the Stax-Volt Fan Club, surrounded by kids from the Soulsville neighborhood. L–R: Deanie Parker, Al Bell, Jim Stewart, Julian Bond. (Deanie Parker Collection)

There’s a difference between playing a club and making a recording, and when the Bar-Kays auditioned for Steve Cropper on a Saturday morning, Steve didn’t think their cover songs showed promise. James Alexander remembers him saying, “I just don’t think you all got what it takes.” Undeterred, the Bar-Kays practiced harder.

“Soul Finger,” the song that would establish them upon its spring 1967 release, grew from their club gig. They were working at the Hippodrome on Beale Street, among the top-tier clubs on what was still the South’s African-American Main Street. Too young to be in the club, too good not be there, they were vamping at the end of another song and fell into a musical pattern that made them all take notice. “When it was done, nobody said anything,” James remembers. “We looked at each other like, There’s something to this. We ain’t thinking this could be the start of a record or anything but we don’t know what it was, because we’re still young.”

They came back and auditioned again for Steve. They’d worked up an instrumental titled “Don’t Do That,” a horn-and-guitar exchange with a popping snare drum that was getting hot in the clubs. Perhaps Steve’s ear had become tired or his patience had worn thin by the steady flow of auditions; he still didn’t hear it. “When we were leaving the studio, Jim Stewart saw us and said, ‘Why are you guys up here?’ We’re feeling kind of low, and we said, ‘We were just auditioning for Steve Cropper.’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you what. I want you to come back up here on Sunday and audition for me.’”

When they played their original for Jim, he was impressed. He was also attracted by their youth; Estelle had been hounding him to consider creating a new studio band, both to give the MG’s a break and to infuse new ideas into the scene. Trumpeter Ben Cauley remembers that Jim stepped away from the studio for a moment, and while he was gone, they returned to the groove they’d stumbled onto while vamping at the Hippodrome. “I’ll never forget it,” Ben says. “He came back and said, ‘Fellas, what’s that? Do it again.’ We played and he said, ‘Let’s cut it right now.’”

The song needed an introduction, and Jim needed to set audio levels for recording. “He ran up into the control room and said to run it down,” James says. “It wasn’t a big elaborate studio—just a little recording board, he turned a few knobs. You didn’t even have a talkback button, you’d send hand signals. Ben came up with this nursery rhyme horn lick, Jim gave us a signal to play it from the top, and when we recorded it, we had ‘Soul Finger.’”

Well, they had most of it. Jim played it at the staff meeting that Monday morning, and David Porter suggested putting teenage party sounds on it. “David told us to find some kids and have them come to Stax after classes,” James says. “He went to the College Street Sundry, across from Stax, and bought a case of the short Cokes in the little green bottle. The deal was if all these people hollered and screamed and shouted on our record, you get a free Coca-Cola.” Porter set up a mike in the studio and recorded the kids while copying the master track onto a new tape—the overdubbing process at the time. He cued them when to shout “soul finger” and gave the song a party atmosphere.

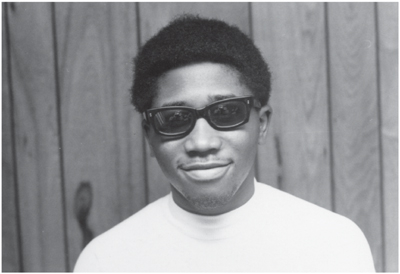

James Alexander, bassist in the Bar-Kays. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

The record was released in April of ’67 on Stax’s Volt subsidiary, most of the band still in high school. The flip side was another instrumental, this one written by Cropper and Booker T. Jones, featuring Jones on harmonica. The song was named “Knucklehead” in honor of James Alexander. “My nickname was Knuck, which comes from Knucklehead Smith [the name of a ventriloquist’s sidekick from a late-1950s TV program]. I was always slow to learn my part, and when Isaac and David would be teaching us stuff, they had to keep going over it with me.”

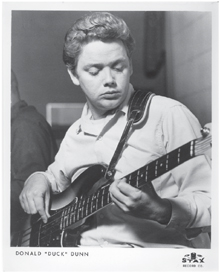

The single creeped, then leaped to national attention, with “Soul Finger” hitting number three on the national R&B charts within two months, and a whopping number seventeen on the pop charts. This affirmation of their talent led to more after-school work for the boys, the kind that didn’t require shoe polish or carrying other stars’ clothes to the dry cleaners. “After the MG’s were getting really busy, I started filling in for Duck Dunn,” James says. “Duck wanted to be on the golf course, and he’d call me.” Other Bar-Kays also began to get studio experience. The family feeling was revivified: The kids had grown, a new generation was coming up.

![]()

It had been a thrilling realization the previous year that the Beatles had wanted to come to Stax. It made all at the label aware of the range their radiance had reached. Now, in 1967, plans grew for the label to send a group of artists to England and across Europe. Many at Stax had never been outside Memphis’s Shelby County. Europe was a distant place that had been discussed briefly in geography classes long ago, where people spoke in languages that couldn’t be understood; they lived in castles and ate snails.

The tour grew out of Otis’s previous visit abroad. Audience reception had been fantastic, and the visit’s problems were minor—Otis said the lemonade came syrupy and with small bubbles in it, and the food was weird, but the band found a fast-food chain with burgers recognizable enough to eat before each show. The promoters reached out to Phil Walden, Otis’s manager, to discuss a return, perhaps on a larger scale. Phil brought the idea to Jim, who discussed it with Al Bell. Otis had been planning a break from the road and he’d broken up his band; perhaps the MG’s could back him. Al liked big ideas, and in short order a Stax Revue was lined up: The MG’s would anchor as the house band, the horns would receive separate billing as the Mar-Keys, and the lineup would include Otis, Sam and Dave, Eddie Floyd, and Carla Thomas, though she’d have to depart early to fulfill some previously arranged US obligations. The bill also included Arthur Conley, a fellow Georgia artist that Otis had signed to a record label he was developing, an enterprise with Joe Galkin, Jotis Records (derived from the usual christening pattern, “Joe” and “Otis”). Conley broke big, going to number two on both Pop and R&B with “Sweet Soul Music,” penned and produced (at FAME Studio in Muscle Shoals) by Otis. William Bell, invited, was already committed to dates in the US. Rufus Thomas was not asked along, which he felt was unjust; Stax said the final lineup was dictated by EMI, their distributor abroad, who knew which artists would be popular. “Otis,” Al Bell says, “was opening doors for all of us at Stax.”

Though the MG’s had recently gone onto salary at Stax, the horns had not, and they were still rushing from sessions to make their fifteen-dollar gigs. Wayne Jackson was working at Hernando’s Hideway, what he calls “a redneck joint,” alongside saxman Joe Arnold, who was also enlisted for Europe. They went to the club’s owner to arrange time off and he told them if they left, they couldn’t come back. “I really was worried about that, too,” says Wayne, “’cause I was working there seven nights a week and I needed that fifteen dollars.” But the lure of travel was too great; as far as they knew, they’d never get to Europe again. Fortunately, they quickly had no regrets: “That door closed and other doors opened,” says Wayne, “and we walked right on through, kept on going.”

(Earlie Biles Collection)

New thresholds beckoned the moment they disembarked. Crowds at the London airport were holding signs and cheering their arrival. The hubbub continued as they realized that the Beatles had sent their Bentley limousines to transport them from the airport to the hotel. “Maybe,” saxman Andrew Love remembers musing, “they like us over here.”

The tour ran from March 17 to April 9, 1967, beginning and ending in London, with stops throughout England and in Paris, Oslo, Stockholm, Copenhagen, and the Netherlands. The executives at Stax, wanting to make the most out of the trip, decided to record several of the shows; Atlantic liked that, and Tom Dowd was enlisted—he and Jim had developed a solid working relationship in the studio. The bands flew over first, allowing them to recuperate before the gigs began. “I flew with the bands,” says Tom, “and then I flew back to escort Jim Stewart and Al Bell to Europe because they’d never flown across the ocean and they were skittish about it.” The night of his return, Tom recorded the first London show. “They had their chops and it didn’t matter where they were in the world.”

(Earlie Biles Collection)

(Earlie Biles Collection)

Before the first public show at the Finsbury Park Astoria, there was a private show for invited guests at the Bag O’Nails, a small London club. “Paul McCartney was there,” Carla says. The Beatles were working on Sgt. Pepper, and he’d taken a break to come hear his colleagues live. “He stayed through the whole night. It was a real intimate place. He came back and introduced himself. And we all sat at a table and talked to him. It was a mutual admiration society.”

The entourage traveled on a bus, playing packed concerts to enthusiastic response, and sightseeing informally. Wayne Jackson and Duck Dunn acquired home movie cameras and began rolling film as soon as the plane got above the clouds; there were lots of things they’d never seen before. “When I was a little bitty girl,” Carla continues, “it was almost as if the Lord spoke to me and said, ‘You’re going to be doing a lot of traveling.’ I thought I would be in the air force or something. I had no idea that I would be traveling as a singer.” The downside to traveling, like Otis had warned, was that the food in Europe was not what they were accustomed to. “All I could eat was boiled eggs and baked potatoes,” says Duck. “The rest of it was just horrible. The lettuce was like wet newspapers. It was a great time, but it was also the longest weeks of my life.” At an English lunch one day, Duck summoned all the foreign words he could muster from the fancier menus he’d seen in Memphis restaurants and told the waiter that he’d like an order of “fatback cacciatore.” Communication gap, soul style.

“I always compare it to what happened when the Beatles first came to the States and they had all these screaming teenagers rushing them,” says Steve. “That’s what happened for us.”

“The barriers, the people standing outside the theaters waiting to see the show,” affirms Eddie Floyd. “And we were nervous, didn’t know whether the Europeans are going to like the show. But we know the music and so we put the music on, and they liked the music.”

In fact, they loved the music. Prior to their arrival, radio stations had Stax in heavy rotation—the latest music, and the already classic songs like “Green Onions” and “Last Night.” The band would hit nightclubs when they had the chance, and Steve immediately noticed that the records’ bass sounds hit harder—the European mastering and pressing drew out more bottom, making them more danceable.

And at the shows, the audiences couldn’t be held in their seats. Carla had them dancing to “B-A-B-Y” and won their hearts with her version of the Beatles’ “Yesterday.” Arthur Conley became the new artist to watch, his “Sweet Soul Music” an irresistible battle cry. Eddie Floyd, Sam and Dave, and Otis Redding presented the problems that every promoter embraces—each one is dynamic enough to close the show, so what order should they go in? The artists hadn’t toured as a group and most had not seen how the others performed. The results were eye-opening to everyone. Otis, having been to Europe, had to climax, and Eddie preceded the duet because they were double dynamite. They were so explosive that they became a problem for Otis Redding. “We came on and we broke out,” says Sam Moore. “Whoa! We were like mad animals. We went at them, singing and sweating and twisting and turning and spinning and—and the European people went crazy. They just went crazy.”

Sam and Dave ended their set with “Hold On, I’m Coming,” and the energy that song drew from the audience could never be anticipated. “Sam and Dave got these people going,” says Steve, “got them dancing and they’d run through the aisles.”

The Stax Revue was taking the Europeans to church, or as near as most of the audience would get to a Mississippi Baptist congregation. “They had to get a mop out there to wipe some of Sam and Dave’s blood and guts off the stage,” recounts Wayne Jackson, mostly figuratively. “They were just slopping in their own sweat. Their clothes were wringing wet. We were wringing wet. One of them would just faint, fall out, they’d drag him offstage. And then Sam would say good night . . . and here they come, back out and starting again. They had everybody just in pandemonium. And Otis would stand over there on the side, watching.” More than once, the crowds got so out of control that security interrupted Sam and Dave’s set to restore calm, threatening to forbid their return to the stage—for the safety of all concerned.

The problem for Otis Redding was that he had to follow them and, unless he wanted to be upstaged, he had to outdo them. Otis was a recording artist who understood the dynamics of a song, but as a performer, he was just learning about stage movement. “Up to this point, Otis had been like Sam Cooke and Jesse Velvet,” says Al Bell, “a great balladeer, standing at the microphone, and he’d sing and move the audience, ’cause he had that passion and that tear in his voice.” Otis didn’t dance like James Brown. From his place at the center microphone, he’d sing with feeling, make eye contact with the audience, twist his upper body, and stomp his feet—but he rarely left that center stage. Watching Sam and Dave from behind the curtain, he knew he’d have to add extra oomph.

“Otis is standing in the wings and he’s nervous,” Al Jackson told an interviewer in the early 1970s. “From the time we started, from the Mar-Keys to Arthur Conley on down, that whole show didn’t lighten up. He’s seeing that reception that Sam and Dave is getting and he ain’t digging this at all. And so he got ready to get out there. The cat introducing him says ‘O-T—’ I’m sitting there just as ready as he is and when the host says, ‘Otis Redding’ I go ‘One, two, three—’ and Otis transformed. I didn’t believe it. When he hit that stage he had a smile on his face and he was there, all man. ‘Here I am.’ He’d grab that mike and that’s all he’d do for that whole forty-five minutes was prowl that stage. I used to sit there and wonder how he did it. That son of a bitch was all man.”

Al Bell saw the same transformation. “He was just like a thoroughbred racehorse waiting for the bell,” he says. “When Sam and Dave finished, Otis Redding broke from behind that stage and grabbed the microphone, and he started going from one end of the stage to the other. I couldn’t believe what was going on—the energy that I had never seen before!” Once, after following Sam and Dave, Otis was heard to mutter, “I never want to have to follow those motherfuckers again.”

In addition to the battles on the stage, there was some in-fighting off the stage. To everyone’s surprise, Otis got better lodging than they did; some of the shows were even billed as the Otis Redding Show instead of the Stax-Volt Revue. Another simmering tension came to a head, this one between Steve and Al Bell—once so close they’d written songs together. Steve, who had wielded authority at Stax long before Al arrived, saw that Al was exuding a new confidence. Indeed, Stax’s sales had risen dramatically since his arrival, and their prominence—now on two continents—was largely attributable to his promotional work. A showdown seemed inevitable. It occurred in Al Bell’s hotel room, where a tour meeting had been called. “Some things were said,” says Steve. “There were bad feelings that I never, ever got over.” Al coveted the clout that Steve had as the label’s A&R director, the ability to sign new artists. The sensitivities of what transpired behind closed doors remain raw decades later, and details are not discussed. “All of a sudden, I wasn’t A&R director anymore,” says Steve. “I was still a member of the band. I was still making the same money. But I had no stick. My stick was taken away and given to Al Bell.”

That summer, Al was promoted to executive vice president. Other changes transpired after they got home. Wayne and Andrew were finally put on salary; if the rhythm section was getting proper treatment, why not the horns? But the biggest changes were in self-perception. Having been exposed to the wider world, they realized the impact of the place they’d carved in it. “Europe changed everybody’s perception of themselves,” says Steve. “That Stax-Volt tour gave us a new insight to what the world really thought of us, ’cause we didn’t think outside the block we lived on. But all of a sudden, we got a sense that the whole world is listening to what we’re doing.”

“The tour was certainly enlightening for all of us,” Jim Stewart understates, “a watershed moment. We were no longer the funky little company on McLemore Avenue. What can we do to enhance our position in this world market? We began to become more business oriented, looking for larger margins. It was like the light flashed on and now we were dealing with a different level. It’s mind-boggling.”

“The world to me at that time was the United States of America,” says Booker. “The European tour was like the Indians meeting Columbus, a huge eye-opener.”

“It was amazing to have all-white audiences, standing room only, and to be treated by the bellhops or attendants at the hotels and other people like stars,” says Al Bell. “We hadn’t felt that or experienced that before.” This sense of respect that he felt proved transformative, both on a personal level and on his goals for the company. Coming from a land where his skin color often obscured his worth, Al was recalibrated by strangers treating him as a whole man, a citizen of value. “Although the music came from an integrated group of people, Europeans viewed it as blacks’s music, as a music that came from a culture. I realized, The world says this is a legitimate, authentic music, and it should be respected and appreciated as a music of that black peoples’ culture. That’s what I felt and received and understood in Europe. And that caused me to move to another level in my thinking of how we would promote and market our product in America.

His determination as a record promoter was rejuvenated, fortified. “We hadn’t been getting our records into many of the larger stores that catered primarily to whites. But I became very aggressive and demanding with respect to that. Europe let me know that the sales potential is out there. And that sales potential justifies us making that kind of investment into our product, even though, at that point, the industry was not enthusiastically positioning our product. I didn’t stop. I mean, I just didn’t stop. Don’t tell me, ‘No, it can’t be done.’ I see it. I was on the kill to take Stax and those artists to that level of appreciation in this country.”

Their horizons widened, deepened. They’d flown on a plane now, and their thoughts, goals, and visions soared like never before. They had experienced their own power, seen and felt the response they summoned. Otis was undeniable as a superstar in the making, Sam and Dave too. The potential everyone felt was unbounded, the possibilities overwhelming.