After the loss of someone close, we seek solace in the familiar, comfort among others with whom we share similar bonds. Routine actions, longtime friends—the heightened appreciation for the mundane—these come into high relief. Assessing its new, bleaker world, Stax sought the balm of the ordinary but found instead yet more encroaching change.

Stax Records was an independent record company, its home in Memphis, its owners and staff in the same building as the studio, as the mailing room, as the retail record store. But to get the records into the stores, Stax was under the Atlantic Records umbrella. Stax found the talent and made the recordings, shipping the master tapes to New York; there, Atlantic pressed and distributed the recordings, keeping the lion’s share for its expenses and its effort, paying a royalty to Stax. Atlantic was older and larger than Stax and the other independents it had similar deals with; it had earlier faced the same retail problem, and it conquered that by creating a distribution network: If stores could come to Atlantic and order not only Atlantic’s product but also those of other independent record labels—Dial with hitmaker Joe Tex; T-Neck with the Isley Brothers; Moonglow with the Righteous Brothers—then the smaller labels could have a shot at competing with Warner Bros., with Columbia, with RCA. Stax, then, was its own entity, but its arms and reach were through its association with Atlantic.

By the middle of the 1960s, the business world in America was rumbling toward conglomerates. Big corporations were buying big companies to become more massive, making it harder for the independent companies to find sunlight and grow. Warner Bros. had just been purchased by Seven Arts, and the new company (that would soon sell to a corporation built from New Jersey’s commercial parking lots) was buying Atlantic Records for breakfast. Offered $17.5 million in late 1967, Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun couldn’t resist selling. And as part of the deal, they would continue to run the company. From out of the sky fell a little piece of heaven.

But their nirvana was another’s hell. First Stax negotiated with Atlantic. Jim, Estelle, and Al even flew to New York to discuss joining Atlantic in the Warner deal. “What Jerry offered me was an insult for the company,” says Jim. “We were supplying Atlantic with a lot of hit records. A lot of hits. We were a big portion of their 1967 sales. That’s why I was totally astounded when they came to me with some ridiculous offer.” Jerry had become a mentor to Jim, making the situation that much harder for Jim to accept. “I took it as a personal thing. You realize how many millions of dollars we’ve run through that company since 1960. Seven years, and their total outlay of money from 1960 through ’67, their cost to get that deal, was five thousand dollars. From there on they never had one penny invested, not even in production costs. They were using our money all during that period of time.”

Jim went to Warner Bros. directly, but the offers were still meager, and he’d have been foolish to accept them. Fortunately, Jim had an escape: At Jim’s request, the 1965 contract had a key-man clause. That meant that Jim trusted Wexler, and if ever Wexler divested his Atlantic stock, Jim could choose to terminate the relationship. The sale to Warner triggered the key-man clause, and Jim—with Estelle and input from Al Bell and other key figures—had six months to find a new company to ally with.

And then more bad news came in. “Of course, there was a contract,” says Wexler, quickly adding, “and it turned out that there was a clause whereby we owned the masters.”

A “clause whereby we owned the masters” meant that Stax owned nothing. It meant that all right, title, and interest in the records belonged to Atlantic, including any rights of reproduction, with Stax having no ownership, no control, and due only about a 15 percent royalty. It meant that Atlantic owned everything that it distributed for Stax—even though it said “Stax” on the label, even though Stax had paid all the money associated with those recordings and Atlantic had paid none and was at risk for not a single penny, and even though Jim and Estelle had operated for years believing their work was their own. Suddenly they were tenants of their destiny; they were sharecroppers, with nothing to show for their labor but a promise. The contract that Jim signed in 1965, formalizing the handshake, actually did not formalize the handshake but rather it slipped handcuffs on him, establishing an entirely new relationship, a very good one for Atlantic and a very bad one for Stax.

Wexler, well-spoken and widely read, a degree in journalism, continues, “I didn’t know this. I never read contracts. I trusted my lawyers. And when I protest about this, people think, Well, here’s a record executive who stole this thing from these poor people and he’s copping out. I didn’t know it. And when we were severing from Stax, it came to my notice that we had ownership of the masters. We were being bought by the Warner complex. I went to [the Warner head], I said, ‘I want to give these people their masters back.’ I said, ‘It was just a dirty trick played on them.’ They said, ‘No way, this is corporate property.’ Now, whether or not Jim Stewart and Cropper and the people down there believed it ultimately, to this day, I don’t know.”

“Jerry and I operated under a gentleman’s agreement until ’65,” says Jim. “I had not read the fine print in the distribution agreement. In ’65, I allowed that to get by me. So, I suddenly realized that I’m in the record business and it’s all not peaches and cream. I love Jerry, but we had a serious, serious argument.” The clause that Jim had not noticed and never read was almost exactly halfway through the thirteen-page contract. With as much information on one side of the clause as on the other, one might say it was buried—the clause that indicated Jim agreed to “sell, assign, and transfer . . . the entire right, title and interest in and to each of such masters and to each of the performances embodied thereon.” Elsewhere, the contract had another clause, this one making the agreement retroactive to include every record that Atlantic had ever distributed for Stax. Consequent discussions were both over the phone and in New York; Jim remembers Ahmet present in Jerry’s office “to smooth things over when things got rough.”

It was corporate homicide—polite, sterile, and deadly. It also clarified the low offers Jim received from both Atlantic and Warner Bros.; if they knew they owned the masters, they wouldn’t need to bid high. The news about Stax’s loss was delivered to Jim by Jerry well into their negotiation. By not revealing the information earlier, and with the clock ticking for Stax having to find a new distribution arrangement, Wexler was heaping injury upon insult, making their situation dire.

“Oh, they were aghast,” Jerry says. “I said, ‘I’m really distressed. Believe me, I didn’t know it.’ How could I expect them to believe me? It really is one of the worst things that ever happened—abuse in the record business. They made the masters, they paid for them under contract, and my clever New York lawyer winkled the masters away to our benefit and not my knowledge. ‘What’s wrong with you, Wexler? Don’t you read your contracts?’ No.” (The fact against which Jerry doth protest so much spilled forth within the first couple minutes of my conversation with him, responding to my inquiry how he, in New York, had heard of Stax.)

Reeling from the loss of the catalog—not yet able to comprehend it, to absorb and react to it—Stax got more bad news from their longtime pals at Atlantic: Sam and Dave, who had been vying with Otis as Stax’s leading act, were being yanked back to Atlantic. Since Otis’s death, they had assumed the label’s lead position. Their latest single, “I Thank You,” was bold in its spare arrangement, emblematic of the new generation finding its own voice. Their albums had come out on Stax, their royalty had been paid by Stax, all of their creative decisions had been made by, with, and at Stax. But Wexler claimed that when he’d first brought the act to Stax, they were signed to Atlantic and had only ever been loaned to Stax. “We gave them Sam and Dave on lease,” Wexler explains. “When the deal broke with Stax, Jim had no cognizance of that. And I said, ‘Hey, since you’re leaving, Sam and Dave will come back to us.’ He was aghast, had no idea.”

“Sam and Dave at Stax was a family thing,” says Sam. “That chemistry works. And when you separate that nucleus between those four people—Sam and Dave, Hayes and Porter—something happens. It wasn’t going to work. So, when they broke that mold, it all went downhill. Jerry had us down in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, but he couldn’t pull the magic off, he really couldn’t.” Sam and Dave never had another hit.

Atlantic’s failure would be no consolation. It was one bad deed after another. “We said, ‘Wait a minute,’” says Steve. “‘That’s not what you said, and that’s not what you implied,’ but then they go, ‘Well, yeah, but the paper [contract] says this.’ Well, there didn’t need to be any paper in the first place. And when you were told one thing and then later, it becomes something else—it was bad business and got kind of ugly. We’d contributed a lot of success to [Atlantic] since the early sixties. We all felt that we deserved a little bit better. It’s called trusting somebody. And the world has been built on trust and when somebody goes back on their word, then hey, it’s pretty devastating.”

![]()

The devastation was just beginning. They’d lost Otis and they’d lost Sam and Dave. They’d lost every record they’d ever released. And in April of 1968, Martin Luther King stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, the Stax home away from home, and took an assassin’s bullet. Nothing in Memphis would ever be the same.

Events leading to Dr. King’s assassination began on January 30, 1968, when a superintendent in the Department of Public Works sent home twenty-two African-American sewer workers during a morning rain. “They cut the crew and ’fore the crew leaves the barn,” said one of the men, “the sun would be shining pretty, but still us go home. White men worked shine, rain, sleet, or snow.” The next day, T.O. Jones—the former garbageman who’d dedicated himself to forming a union—held the twenty-two sewer workers and demanded the men receive a full day’s pay, not the compensation pay of two hours (less than two dollars). The commissioner agreed to review the department’s rainy-day policy, and the men returned to work.

The next day, February 1, an AFSCME field representative flew to Memphis, meeting with the commissioner to ask, on behalf of the sewer and sanitation workers, for more: a written grievance procedure and a union-dues checkoff (the option to pay union dues directly from the department). Later that afternoon, during a driving rain, two sanitation workers took refuge in a truck’s hull, riding where the garbage was thrown in; there wasn’t enough room for a whole crew to get in the truck’s cab. A shovel slipped while the truck was en route, causing the crusher to engage. The driver heard the packing engine turn on and quickly halted, running outside to mash the stop button. A woman at her kitchen table saw the truck, then heard the screams. “It was horrible,” she told the newspaper. “[One worker] was standing there on the end of the truck and suddenly it looked like the big thing [the crusher] just swallowed him.” This make of vehicle had been purchased by Commissioner Loeb in the 1950s, and the workers had insisted many times that it was unsafe. Two workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death.

Henry Loeb had been reelected mayor and sworn in the prior month. He’d been hearing—and not heeding—the sanitation department’s complaints for more than a decade. Loeb, who’d received 90 percent of the white vote, gave the families of the recently deceased garbagemen a month’s pay (less than $200) plus $500 toward the burial expenses of $900. The city had failed to maintain its trucks, and shrugged at the consequent ruin; each family was immediately destitute. Then payday came, Friday, February 9, and the twenty-two sewer workers found no increased compensation despite their returning to work. More deaf ears and delaying tactics. (Jones later observed that the whole strike could possibly have been averted for less than forty-four dollars, two additional hours of pay to the twenty-two men.) Finally, it was too much.

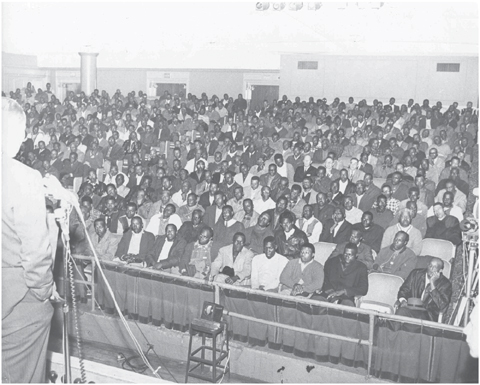

On Sunday, February 11, nearly one thousand sanitation department employees overflowed a meeting hall and vented their anger. T.O. Jones led the assembly and organized the basic grievances: These men were making less than seventy dollars per week, and forced to work overtime with no compensation; the equipment was faulty and dangerous; they wanted union representation without fear of being fired; they wanted a restroom, and showers, and uniforms; they wanted to be able to advance in the department, and they wanted an acceptable wage on rain days.

The head of Public Works would concede nothing, and refused to even come address the assembled men. No strike was called, but the next morning, Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, about 1,150 of Public Works’ 1,300 employees refused to work; many who did work quickly returned. There was no picket line, no leaflets, no union organization, and no strategy; this was a wildcat strike, and there was only anger and the determined will for justice.

AFSCME representatives scrambled to town, including Jesse Epps, who would soon move there to lead the AFSCME local. Mayor Loeb’s term was the first for a new form of government, switching from the good ole boys’ club of the mayor and four at-large commissioners to a mayor and thirteen-member city council. Racial progress was kept at bay by composing the council of only seven district representatives, with the six others “at-large.” Blacks, who composed 40 percent of the city, had tried to negotiate ten districts with three at-large and were stymied; they were able to place only three representatives on the council. Loeb assumed that AFSCME perceived Memphis as weak during this transition period and had provoked the situation as a way to swoop in; there was no substantiation for such an opinion then, and none has ever turned up. When Loeb told an assembly of workers that striking was against the law—“This you can’t do!” he barked at them—the response was laughter. He stormed out, and AFSCME’s Epps later said, “That was the first time in the history of Loeb’s life that he was no longer the master. There was an insurrection among the slaves . . . And he just drew the line.” The Staple Singers, who were about to sign to Stax, would voice the sentiment of these and all African-American workers with a song from their first Stax album, “When Will We Be Paid (for the Work We’ve Done).”

Mayor Henry Loeb, left, addresses striking sanitation workers, Memphis, 1968. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

“The garbagemen were a part of the fabric of the society,” explains Booker T. Jones. “My father always taught me to shake their hands and say hello to them. Know who they are. They were closely interwoven into the African-American community. So their fight was everybody’s fight.”

“Mayor Loeb’s attitude was, ‘The hell with ’em!’” says Marvell Thomas. “People were tolerant of each other, even if they weren’t all that trustful. But Loeb was so intractable that he made a chasm between the black and white communities.”

The strike was national news before the arrival of Dr. King. Mayor Loeb, entrenched, stated to his associates, “I’ll never be known as the mayor who signed a contract with a Negro union.”

Despite constant attempts at negotiation, the striking workers found City Hall obstinate. Within two weeks, there was a police confrontation involving mace (a newly introduced chemical weapon). Within a month, the mayor requested that the National Guard begin riot drills. Recommendations for resolution from the state legislature were ignored. The newspaper claimed that scabs were mitigating the strike, but when Dr. King paid a first visit, seventeen thousand people came out to hear him say, “Whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity and it has worth . . . You are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages.”

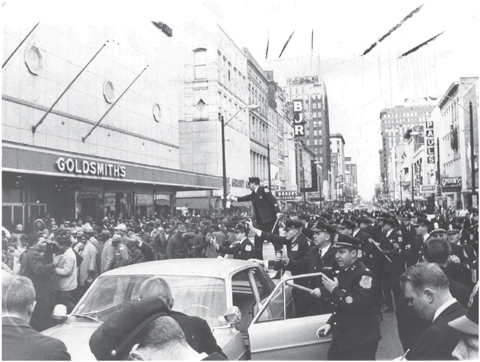

March 1968, Main Street, Memphis. Police spray mace on a sanitation worker’s march. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

“Really, Dr. King was preaching what we were about inside of Stax,” says Al Bell, who had worked and studied with Dr. King since the late 1950s, “where you judge a person by the content of their character rather than the color of their skin. And looking forward to the day when, as he said, his little black child and the little white child could walk down the streets together, hand in hand. Well, we were living that inside of Stax Records.”

“Pops heard Dr. King speaking,” Mavis Staples explains, referring to her father. “We’d been all over singing our gospel. We were in Montgomery, Alabama, one Sunday, so all of us went to Dr. King’s eleven o’clock service, Dexter Avenue Baptist Church [before he moved to Atlanta]. Pops talked to Dr. King for a while and when we got back to the hotel, he called us to his room and he said, ‘I really like this man’s message, and if he can preach it, we can sing it.’ And that was the beginning of our freedom songs. When we signed with Stax, 1968, we were singing message songs. We made that transition from strictly gospel to protest songs, freedom songs. And it seemed that Dr. King was getting the world together.”

The strikers began daily marches down Main Street. They wore signs, some stating the painfully simple I AM A MAN, a fact that the city government, for years and decades, seemed intent on ignoring. These marches were not led by bullhorns, nor by chanting, protests, or group song. These marches were silent. To the sound of their own hushed footsteps, hundreds of African-American men and women traversed the length of Main Street, from Clayborn Temple to City Hall and back. (My father worked on the twelfth floor of a building on Main; his office overlooked the street. In 1968, he brought my brother and me to his office, had us open the window and look down. The image seared. The silence roared.)

On March 28, Dr. King’s peaceful march was violently disbanded by police. Stores were looted and Larry Payne, a sixteen-year-old black child, was killed by a policeman’s shotgun blast. Tanks, armored cars, and rifle-bearing National Guardsmen filled the streets of downtown Memphis. King, intending to negate the violence with a peaceful march, planned another stand in early April. By March 29, President Johnson got involved; Loeb rebuffed him.

Young Larry Payne was buried on April 2, his funeral amplified by the hundreds of supporters and by the raging emotions. The following day, Dr. King spoke at Clayborn Temple. There’d been death threats, serious enough that each time the window’s shutters clanged against the building, Dr. King and his associates reacted with a jolt. The shutters were finally locked in place. He spoke of “difficult days ahead,” then said, “I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land!”

The next evening, in Memphis, at the Lorraine Motel, Dr. Martin Luther King was shot dead by a single bullet.

“It wasn’t just that it happened in Memphis,” says Booker. “He was shot at the Lorraine Motel and the Lorraine Motel was where we had our meetings on Monday morning. We used their dining room for our meeting hall and the Lorraine Motel was the place where Steve Cropper and Eddie Floyd wrote ‘Knock on Wood.’ We ate there on a regular basis. It was an institution for us. And so it couldn’t have been any closer had he been shot at 926 McLemore [Stax’s address].”

The day after Martin Luther King was assassinated, Mayor Henry Loeb greets a coalition of Memphis ministers with an outstretched hand. At his feet, he has a shotgun at the ready. (Commercial Appeal/Photograph by Robert Williams)

There was rioting across the nation. Windows on Beale Street and Main Street were smashed, businesses looted and destroyed. Fires were set. But the National Guard had been withdrawn from Memphis only two days earlier, and they were easily recalled. Several artists appealed for calm on the radio, Isaac Hayes, David Porter, Rufus Thomas, and William Bell among them.

The day after the murder, Mayor Loeb held a large meeting with ministers and clergy from across the city. There is a photograph of him extending his hand to shake and make peace with men of God who had come in large number to his office. The photograph is taken from behind Loeb at his desk, and at his feet, he has stashed a shotgun. The hand may be extended, but the weapon is at the ready.

“It was the type of thing that happened and then you—you can’t see a solution,” says Booker. “There’s no solution. There’s no arrest that would help. There’s no way to fix it.”

Jesse Jackson had the same thought, and his solution was to not become derailed. “We were determined not to let one bullet kill the whole movement,” he says. “Right after Dr. King was killed, we determined to focus on what killed him, not just who killed him in sick society. And it was a mad struggle for identity. We had lost our leadership. The ship had lost its rudder. And I remember we regrouped and kept going to Washington with the Poor People’s Campaign. We didn’t spend a lot of time, frankly, in Memphis trying to find the killer.”

“As a testament to how the neighborhood valued Stax Records,” says William Bell, “a lot of the places were either broken into or burned—everything around this neighborhood. Stax was left standing and untouched.”

“Jim, Steve, and two or three others loaded up the tapes we had in the back,” explains Estelle Axton, “because those tapes were a lot of investment. They put them in the trunk of the car. We closed our business, I closed the shop. We stayed closed, the shop and the studio, for about a week, because we wanted to respect the people. We didn’t know who thought what and what would happen, so we just closed our doors and never knew whether the building would be damaged—but it wasn’t. We were protected because the people in the neighborhood, they respected us enough to not harm a place that talent out of their community was using.”

“They were burning down the buildings next to us,” says Jim. “They burned the laundry across the street, all kinds of things, but by that time, people understood that we were a good effect on the community.”

“When Martin Luther King was killed,” says Rufus Thomas, “that changed conditions in the whole world, and especially in Memphis. The death of Martin—the whole complexion of everything changed.”

Windswept.

Sideswiped.

President Johnson sent James Reynolds, his undersecretary of labor for labor-management relations, as a special emissary to settle the strike, calling him often to find out why talks dragged on. Twelve more days passed, filled with sorrow and anger; humiliating and bitter days as the pharoah’s heart hardened. Reynolds finally negotiated for the dues checkoff to come indirectly from a federal credit union; he negotiated for Loeb to pass to the city council the task of recognizing the union, relieving him of the burden of responsibility, and also accountability. When the city balked at the last minute on the pay raises, an anonymous businessman donated $60,000 dedicated to their pay. On April 16, a memorandum of understanding was ratified between the two sides: The City of Memphis recognized the sanitation department employees as men. They recognized their union, gave them a written grievance procedure, agreed to end discrimination on the basis of race, and improved their working conditions. The terms were quickly ratified by the men inside the Clayborn Temple. T.O. Jones sat on the dais up front, and while others leaped in the air and shouted with joy, he leaned forward, his forehead cupped in his bent arm, weeping quietly.

It was a resolution, but the future was uncertain. “That horrible occasion turned everything around,” says Wexler. “That was the end of rhythm and blues in the South.”

“The heart has a lot to do with the success,” says Jim, “and I think the death of Otis took a lot of heart out of Stax. It was never quite the same afterwards. Then Dr. King was killed. I still love records and music, but that was just a pure time. We were such an emotional group, everybody was so involved. The company was the studio, and it was recording, and it was songs, everybody going to the control room and just going crazy with excitement. After that, something happened.”

Less than a decade earlier, Jim Stewart had known no African-Americans on a personal basis. He’d had no success in the music business, save for gigs in smoky bars between night classes in law. He narrowly missed going under, rescued by his older sister. Since then, every victory had been hard won, every loss personal. But from their corner on McLemore, they’d reached the whole wide world.

The death of Otis and the Bar-Kays dimmed their soul. The pillaging by Atlantic tore at their self-respect. The assassination of Martin Luther King choked their heart. In a state of shock, Stax was a body going cold.