Al Bell rolled up his sleeves. “Hit records are the number one thing on our list,” he said in a magazine article at the time. “Soul music has grown from a particular market to become the new music of the nation,” and he set about making “product [that] is appealing to and accepted by the masses in America.”

Jim Stewart was fully on board with Al’s vision. “This is a corporate change,” Jim explained. “We are certainly proud of our R&B background . . . but now we will merchandise to the mass market. The racks [department stores and drug stores that had racks in a particular area devoted to records] historically have been hesitant to put out ‘black product’ . . . Finally they began realizing they were losing sales.”

Through music, and through the company behind the music, Al could realize the essence of the Black Power platform. Stax could appeal to all people of all races in all places, and bring more jobs—good jobs, high-paying jobs—back home. But he needed a catalog. “I wanted to get as many hit records as possible into the marketplace,” says Al. “Then, we’d bring all of these distributors in and let them know that we are a formidable, independent record company. And the window of time to get this done was just a few months. They said that can’t be done, it’s impossible. So I got together with Steve Cropper and Isaac Hayes, [producer] Rick Hall and the guys in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, Don Davis and his studio in Detroit, and we had productions going on in all of those places at the same time. And I was busy, back and forth on the phone, pumping everybody up and just driving, driving, driving.”

Al’s visionary soul explosion could be made a reality. One compilation album even took that name, Soul Explosion, and the 1969 sales conference, though unnamed, has become known to many as just that: the soul explosion. Thirty singles would accompany what became twenty-eight albums, all created in about eight months. Al Bell signed jazz greats Sonny Stitt and Maynard Ferguson and was seeking a fresh comedian. The studio upgraded its recorder to an eight-track. That made room to establish Studio B, smaller than the A room and using the older gear—but busy. Soon, a C studio was built near the publishing office, a demo studio for writers. There was so much traffic and demand that a chalkboard was put outside of studio A to reserve time, and the three rooms were booked all hours of the day, all days of the week.

Stax took over the whole block of buildings. The staff had rapidly expanded: The sales force included Herb Kole, who brought nearly two decades of experience, including a stint as Atlantic’s East Coast sales manager. Bernard Roberson, an African-American, was named national R&B promotions director, and other promotions men were hired. A New York publicity firm was retained to work with Deanie Parker; New York lawyers were hired, and so were California graphic artists. “They’d knock all the walls out,” says Don Nix, “and they’d rebuilt. It was just one big maze of offices and hallways.”

“Stax was an architectural nightmare,” recalls one visitor, who was buzzed in from the lobby, which was decorated in lavender and purple. “The lavender carpeting instantly changed to deep, deep green. I’d never seen such a clash in my life, until we walked down the hall, and the carpeting suddenly changed to bright red. The color scheme at Stax was shocking.”

The company’s fresh start was emblematized by a new logo. The stack of spinning records had worn thin, and Al and Jim had discussions with Paramount’s art department about an emblem to indicate their new direction, their return to the game, their instant catalog. Paramount delivered: the snapping fingers. “The finger snap signaled a change,” says Al. “Pow. This was the company that’s moving.”

When working the deal between Stax and Gulf & Western, Al had not been shy about his needs. “In addition to getting stock in the sale,” he explains, “we had budgets to operate the company. They understood the need, from a business standpoint, of having a catalog. Built in to those budgets was the cost for putting together that sales presentation.”

“What Al Bell did was to galvanize the creative force of that organization,” reflects Deanie Parker. “He had the writers writing. He had the producers producing back-to-back marathon recording sessions. Of course Jim was a part of it, but Al Bell was the motivating factor. It was like a tornado. I’m serious—like a tornado. We all had a common goal and that was the restoration of that organization.”

“It was somewhat contradictory to my spending philosophy up to that point,” says Jim. “But I’d had a rude awakening when we terminated with Atlantic Records. It’s not a bed of roses out here. Survival is the word. You’ve got to take a stand, and make your presence felt in the industry.”

The soul explosion included a foundational change in emphasis. Stax releases through the Atlantic years had relied on the MG’s, which gave a consistency to the label’s sound, an identity. A Stax release could usually be identified with just a few seconds of play; the music was always unique to the song, but it had readily identifiable characteristics and feel.

No more. The new Stax sound was the sound of hits, whether recorded at McLemore or a foreign land, whether produced by Stax or simply licensed by them for distribution and made by people in other cities that no one at Stax had ever met. If the song appealed to Al’s DJ instincts, Stax wanted it. What Stax sought was no longer about identity, it was about opportunity.

The rush of work kept Jim too busy to engineer sessions, so Ron Capone was hired away from another studio to oversee production. Shocked by how fast and loose the work was being done, he quickly recognized the shortage of production staff. Others were hired and Capone organized weekly Saturday-morning training sessions, designed not only to give a chance for improvement to employees like William Brown from the mail room and night watchman Henry Bush (each of whom would soon engineer hits), but also to establish a sense of basic standards for all the sessions produced at Stax.

Duck Dunn remembers being swept up in the moment. “Al Bell missed his calling,” smiles Duck. “He should have been a preacher. He could put you in the palm of his hand. He did it to me, he did it to everyone. I mean, the man was incredible: ‘Lord gonna bless you.’ Al Bell became God in rhythm and blues. He said, ‘We’re gonna take this company, and we’re gonna turn it into a multimillion-dollar thing.’ And he did it. With Jim.”

“The timing was perfect,” says Deanie. “Jim needed an Al Bell. Stax Records needed an Al Bell. So Al had a series of meetings and he explained what the situation was—how we’d lost our catalog but we’re gonna move on and it’s gonna be bigger and it’s gonna be better than it was when we first started. And we were all young and naïve and energetic, and certainly our love for Stax Records was unquestionable, so we said, ‘Let’s do it.’”

In concept, the soul explosion idea was brilliant. In execution, however, the effort was almost brutal. The “factory” was going to up its output by more than tenfold. “The market was changing toward albums,” says Steve. “Where we would spend months working on four, five, six artists and singles trying to get a hit on them, all of a sudden I’m working on four, five, six albums—ten times as much. The fatigue of the in-house songwriters, producers, and players trying to keep up with the demand was just overwhelming. It was wearing us out.”

Combined with the increased workload was a new system of office procedures dictated by the distant corporate headquarters. New York instructed Los Angeles to instruct Memphis: time management, product quotas, and the like. “I didn’t like the new situation,” says Booker. “We were getting memos as to what time to have the sessions and at one point they had us operating in shifts. That whole concept was so foreign to me. Three shifts with Stax? We started as a company that had trouble getting the drummer to the studio by noon. It wasn’t the same company. It wasn’t the same at all.” This malaise that Booker felt from the conditions was also expressed in the art. “There was an absence of the spirit in the music,” he continues. “The music was coming from a different place. There was a feeling like mass production, a factory or assembly line feeling. I think the arrangements lost their sensitivity.”

“The profit and the amount of record sales increased greatly,” says Steve. “The record company had a lot of hits and a lot of chart action. But I think the quality started deteriorating. And a lot of records had been farmed out to other studios, to other producers, to other musicians that didn’t have the Stax seal of approval. It’s like a great shirt company farming out to some other country to make their shirts and they wear out after three weeks. They’re not the same shirt anymore.”

As the engine revved higher in preparation for the soul explosion, the company released a steady stream of singles, many of which sold well and landed on the charts. Jimmy Hughes stole away from Muscle Shoals and, under the guidance of Al Jackson, he hit with “I Like Everything About You.” Linda Lyndell put the sultry “What a Man” on the charts, the Mad Lads (also produced by Al Jackson) hit with “So Nice,” and the Soul Children’s debut, “Give ’Em Love,” placed well. (Isaac and David created the Soul Children to replace Sam and Dave, using two men and two women to create high-energy songs.) William Bell and Booker T. Jones wrote “Private Number” for vocalist Judy Clay, and Bell’s demo was so good it wound up as a duet with her, made all the more lush by Jones’s restrained guitar playing and his beautiful string arrangement. “Private Number” is classic soul timelessly updated; if there’s less raw funk and juke-joint dirt floor, it is a song built on that same foundation. William Bell was certainly on a roll, releasing three more singles before the sales meeting, all of which landed on the charts, including another duet with Clay.

Money kept coming in, and Stax had no problem spending it. With the vast building to fill, the six vice presidents—each of the MG’s and Hayes and Porter—got their own offices. There was an expanded space for the publishing company. Jim and Al each redecorated their offices. Jim’s looked like the Memphis retreat for Playboy’s Hugh Hefner. He put in slick wood paneling, sleek modern furniture, a TV set built into the wall. Would you like a drink? Step over to the leopard-skin bar and feast your eyes on the sumptuous supine woman in the black velvet painting while the highballs are shaken. His former bank loan customers would have been amazed that this hepster dwelled inside the straitlaced man who’d sat across the loan desk from them. Al Bell’s office was upstairs—the old projection room. “We called it ‘the bird’s nest,’” says the Bar-Kays’ new drummer, Willie Hall. “You go up these steps, a little narrow hall, and it was this little room with a great stereo system, some great speakers, a tape machine to play what you’d just recorded. You go in there man, and Al, he’d be up dancing, and he’d say, ‘Have you heard this? Let me show you this. You got to hear this.’ He would put on songs from Stevie Wonder or the Jackson Five and he would encourage us to try to get those type of productive ideas and production feels. Every time you saw Al, he was moving at a hundred plus.”

Al moved into a large house on the city’s prominent North Parkway thoroughfare. Steve bought a house in the expanding eastern suburbs (his doorbell played “Green Onions”). Jim spent nearly a quarter million dollars on a new home, ten thousand square feet sitting on more than fifty acres, just outside Memphis. He installed four swimming pools, a tennis court, a bathhouse, a party house, and a guesthouse. In December 1968, he threw a lavish Christmas party there. “He had this house that I could not believe,” says Don Nix, who remembered the Jim Stewart who had squeezed all the manual labor from the hapless Mar-Keys when they were building the studio. “Janis Joplin was there. They had a trout stream running through the living room. I said, ‘Look at ole Jim. He’s having himself a good time,’ and I was glad to see it.”

“Those parties were huge affairs,” says Jim’s niece Doris, Estelle’s daughter. “Jim went through a period where he was king of the hill. Mother wouldn’t go to the parties, but they continued to see each other at their parents’ house in Middleton, for Christmas and Thanksgiving. My mother was hurt, but there was never any not-speaking. She was able to be cordial and carry on.” In his big spread, Jim feted Julian Bond and Dick Gregory, bringing in African-American leaders from Atlanta, Chicago, and Memphis. Stax was working every front it could, affirming its vitality, announcing its expansive future.

The company’s success, noted Jim, was rooted in his partnership. “Because of my background as a banker and businessman, I’m considered a conservative, while Al Bell, a wheeler and dealer, is just the opposite. He’s liberal,” Jim wrote in a magazine piece. “Here we are, two opposites with the same goals. Put us together and you have perfect equilibrium . . . If we’ve done nothing more, we’ve shown the world that people of different colors, origins, and convictions can be as one, working together towards the same goal. Because we’ve learned how to live and work together at Stax Records, we’ve reaped many material benefits. But, most of all, we’ve acquired peace of mind. When hate and resentment break out all over the nation, we pull our blinds and display a sign that reads ‘Look What We’ve Done—TOGETHER.’”

![]()

Al Bell was on a signing spree, building a wide and diverse roster. His inspiration was the Vee-Jay label, an indie from Chicago founded by two African-Americans, Vivian Carter and Jimmy Bracken (it went bankrupt in 1966). “I aspired to have a label that was as diverse as Vee-Jay,” Al explains. “They had soul music: Jerry Butler and the Impressions. They had blues: Jimmy Reed, Memphis Slim. They had gospel: the Staple Singers, the Swan Silvertones. They had pop: Gene Chandler with ‘The Duke of Earl,’ and they had the Beatles before Capitol exercised its option.”

Early in 1969, Pervis Staples brought a young Chicago gospel group to Stax. The Hutchinson Sunbeams, three sisters, wanted to go secular, and Pervis convinced them to do like the Staple Singers and join Stax. “We’re trying to carry a freedom message,” Pervis said, explaining that the move from gospel to pop didn’t have to be as radical as some feared. “One reason we changed our way of singing from straight gospel to this new style is ’cause we want to reach more people. And it’s for sure we wouldn’t have gotten to all the concert halls we’ve played so far as a pure gospel group.” The Hutchinson Sunbeams changed their name to the Emotions, and with “So I Can Love You,” a classic Hayes and Porter soul-drenched production, they landed a top-five R&B hit the first time out, crossing over to the pop top forty.

In February, Stax shone at the 1969 Grammy Awards, the nominations including Johnnie Taylor (who’d performed the previous month at President Nixon’s inaugural ball), the Staple Singers, Sam and Dave, and writers Bettye Crutcher, Raymond Jackson, and Homer Banks; Otis Redding won Best R&B Vocal Performance for “Dock of the Bay,” and he and Steve Cropper won as writers for Best R&B Song.

New label distribution deals were announced, more in-house labels were created—Hip, for pop acts, and Enterprise, a jazz and catchall label named for the galaxy-traveling spaceship on Al’s favorite TV show, Star Trek. The hubbub of activity and the accompanying expenditures were so astonishing that Gulf & Western sent representatives from Paramount to see what its new subsidiary was doing. “Almost immediately there was some friction between the executives at Paramount and us,” Jim remembers. “They wanted to control the company, basically.”

“One day in my office on Chelsea Avenue, a bad part of town,” says attorney Seymour Rosenberg, “this little fat guy and a young guy buzzed my door. I thought maybe they were criminal clients and so I let ’em in and the little fat guy says, ‘Do you know who I am?’ and I laughed and said, ‘No.’ He says, ‘I’m the president of Paramount Records.’ I said, ‘Well great. What are you doing here?’ ‘Nobody’s at Stax Records we can talk to. They said you were their lawyer.’ I had a good laugh over that. Here’s a guy making a quarter of a million a year and he’s gotta come to a six-hundred-dollar-a-month lawyer to find out what’s going on with the company he owns. I don’t think Paramount knew what Stax was doing and Stax didn’t care what Paramount was doing.”

The relationship with Atlantic had been organic—built from shared sensibilities; between Paramount/Gulf & Western and Stax, it was just business. Stax could have been auto parts, pet food, or baby wear. “Atlantic loved the music,” explains William Bell. “I don’t think Gulf & Western understood it, or understood some disc jockey down in Monroe, Louisiana, how to get to him or how to even talk to him.”

“It was big fun until Paramount came along,” says trumpeter Wayne Jackson. “They wanted us to be corporate. They sent people who drifted around the hallways, but they didn’t stay around very long. We weren’t the kind that they wanted to go out to dinner with. And they put up a time machine, ka-toonk, and a card with your name on it. You’d have to ka-toonk when you got there, ka-toonk when you went to lunch. They made us fill out time sheets, what you did each hour. After about a week of that, we started putting in, ‘Eleven A.M., cheeseburger at Slim Jenkins’s Joint. One o’clock went to studio and checked on Booker T. and the MG’s. Nobody there, so back to Slim Jenkins’s Joint.’ We made up this long list of crap that the suits would have to read before they wrote the checks and I know it ate their shorts.”

The suits from New York and Los Angeles might not have understood what was going on in Memphis, but they couldn’t deny its success.

![]()

While Stax was piecing itself together, Memphis was furthering its civic segregation. Though fifteen years had passed since the Supreme Court had declared separate but equal schools unsatisfactory and illegal, Memphis and the rest of the nation had done little to act on it. Blacks students made up 54.5 percent of the total Memphis City Schools’ 1969–1970 population, but there were no people of color in positions of authority at the school board. Schools on the largely black south and north sides of Memphis were in disrepair, were afforded only the outdated textbooks recently discarded by white schools, and were saddled with higher student-teacher ratios. The NAACP stepped up its efforts to foment change, demanding more meetings with city officials and demanding representation on the school board. Looking to the success of the sanitation workers in getting their point made, the NAACP began publicly discussing a student boycott. State and federal school funding was based on average daily attendance, and if great numbers of African-Americans began to miss school, it would hit the school board in their pocket.

Meanwhile, as the year since the sanitation strike’s settlement was drawing to a close, so was the memorandum of understanding with the city. Though new discussions had begun in January 1969, no contract was agreed upon by April and, as if to spite the sanitation workers, the city took a unilateral action and passed a fiscal budget that did little to address the wage disagreement. Strike talk was renewed.

T.O. Jones, however, was no longer head of the local. Soon after the strike’s end, the national AFSCME office hired him to help organize in Florida. But once there, he was fired. During his brief time away, his Memphis position had been taken by Jesse Epps, the national representative who’d been in Memphis for several months. The newspaper described Epps as “a short man who walks slightly stooped forward and usually has an examining, pensive look on his face as he pauses between rapid-fire outbursts.” Epps summoned the Public Works employees to Clayborn Temple, scene of the previous year’s meetings. Epps could excite a crowd, and eight hundred sanitation workers cheered him as he shouted, “Strike come July 1!” and “War with Memphis!” He threatened to bring Memphis to a “screeching economic halt” unless union demands were met, including a raise of fifty cents an hour for all employees, which would establish a two-dollar-per-hour minimum (hundreds were making much less). The city was countering with a $1.60 minimum, dismissing the fifty-cent raise as too expensive. The newspaper reported that city council chairman Wyeth Chandler (who would soon be elected mayor) and others “believe that meeting the union demands now would lead to further demands which could not be met.” On the plantation, the phraseology for this thinking was more poetic: Give ’em an inch and they’ll take a mile.

Jesse Epps, left, assumed leadership of the AFSCME union after T.O. Jones. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

By late May, when Stax was hosting its soul explosion, Epps led a “spread the misery” campaign in an upscale white shopping center. His followers intended to fill parking lots to prevent commerce; to fill shopping baskets and abandon them; to fill stores and not shop. Several businesses, seeing blacks amassed at the entryway, simply locked their doors and closed early. By mid-June, a strike looming in two weeks, the city announced that garbage trucks would be placed at central locations where citizens could dump their trash. Various other fail-safes were being planned when, with only days left, a settlement was reached. The city agreed to the two-dollar hourly minimum and conceded the direct dues checkoff (paying union dues from Public Works paychecks instead of indirectly through the credit union); the union gave the city a year to implement the raise, and extended the agreement’s term for three years, having long insisted it be only for two. The sanitation workers ratified the agreement with jubilant cheers. While everyone was assembled, the union won an additional dollar per month per member, bringing members’ total checkoff to six dollars per month; the additional dollar was designated for a community-action program in Memphis that Epps said “would work to feed hungry children and to give aid to the poor and those less fortunate than us.”

![]()

While the union fought the good fight, Stax fought for its life. Twenty-eight albums—about 280 songs. Working from the autumn of 1968 to the May 1969 soul explosion meant writing, recording, and mixing about one and a half releasable songs every day of the week, weekends included.

The pressure fell heaviest on Booker T. & the MG’s. Though other studios were involved, Stax was still headquarters and they were still top dogs. In addition to playing, they were each producing other artists. Because they had to sleep, and since there was a new second studio inside the McLemore facility, Stax looked for another backing group it could rely on. Ben Cauley and James Alexander, the surviving original Bar-Kays, had sought solace in their music. Soon after the plane crash, they formed a new version of the band. The soul explosion gave them an opportunity to hone their chops.

“Me and James was around each other a whole lot,” says Ben. “We had to go on, but we wanted a new thing.” The group they put together was recognizable yet different. The two original members were in place, and a white cat (Ron Gorden) was on the organ, as before. One noticeable difference was that the group had two drummers, a nod to James Brown’s current band; one was Roy Cunningham, brother to original Bar-Kay Carl Cunningham, and Willie Hall played a second kit.

“Stax was very supportive of us,” says James. “We was trying to operate real fast, to get back to recording right away.” The new group’s first single, “Copy Kat,” was released in October 1968. Another came in March 1969, its title pretty much their motto: “Don’t Stop Dancing (to the Music),” a hard-hitting funk breakdown that evokes King Curtis’s “Memphis Soul Stew.” It also introduces Larry Dodson, who’d joined the Bar-Kays as lead vocalist, adding further dimension to their act. The grooves caught the attention of Isaac Hayes.

Al had approached Isaac about making a solo record for the instant catalog. Isaac had made a jazz piano album at Al’s behest a couple years earlier; this time, Isaac asked if he could record his own way. “Al said, ‘Man, you got carte blanche. Do it however you want to do it,’” remembers Isaac. “I was under no format restrictions and I had total artistic freedom. There were twenty-seven other LPs to carry the load, so I felt no pressure.”

Al had watched Isaac produce records and teach songs to artists, and he sensed a star quality not unlike that of Brook Benton and Billy Eckstine—major stars in their day. He knew Isaac was a flamboyant fashion man. “And that bald head,” says Al. “Bald heads weren’t popular back then, but from a marketing standpoint, we could probably do wonders with this guy—he’s different.” Being different—Al knew that’s how you get records played.

The Bar-Kays had a regular gig and one day Isaac asked—well, told—the new band that he was going to sit in with them, and they should learn “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.” A country hit by Glen Campbell the previous year (and more recently redone by Stax’s Mad Lads), “Phoenix” had struck Isaac at first listen. “I thought, God, how this man must have loved this woman,” says Isaac. “I went on the stage, there was a bunch of conversations going in the club, so I told James to hold that first chord and sustain it. ‘Don’t move, don’t change, don’t do anything.’ And I started telling a story about the situation in the song. And the conversations started to subside. Upon the first note of the first verse, I had ’em. And when the song was done, people were crying. I’d touched them. Now, this place, the Tiki Club, was predominantly black. Across town was Club Le Ronde, a predominantly white club. I did the tune there the same way, and the response was the same.”

Bar-Kays drummer Willie Hall, in his late teens, became close with Isaac, who was about a decade older. Willie had finished high school, and when his family moved to Detroit, he’d moved in with his aunt because he didn’t want to break up the Bar-Kays. He remembers Isaac working up the song with the band. “Isaac was one hell of a womanizer,” says Willie. “With so many women, he had some problems. And a lot of the women had their own egos and personalities and problems, and that could spill over onto the rest of the guys. So, a lot of times we would be doing ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix,’ people in the audience would be crying, Isaac would be crying, I’d be crying, the background singers would be crying—because we could relate to the situation.”

Working during the wee hours of the night, Isaac developed four songs. “‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’ was eighteen minutes and forty seconds long,” he says. “We cut it live, right there in the studio. I felt what I had to say could not be said in two minutes and thirty seconds. I was all about feeling.” More than half of the song was the spoken, moaning introduction, the story he’d begun telling in nightclubs to attract the audience’s attention. The album was cut at Ardent Studios—Stax was already booked around the clock. Ardent had purchased the same recording console and tape machine that Stax had, and was drawing their overflow. “The terrifying thing was the length of Isaac’s songs,” says Ardent’s owner and chief engineer John Fry. “A reel of tape ran for fifteen minutes, and Isaac’s songs would run longer. We began splicing extra tape onto the reels. Even still, there were takes when I walked into the studio while they were playing and made circles in the air with my finger. They’d improvise an ending.”

Isaac recorded the basic tracks in Memphis and then brought the tapes to Detroit, where arranger Dale Warren (often with Johnny Allen) wrote and recorded string parts. Isaac put his own stamp on another hit, the Bacharach-David song “Walk on By,” which Dionne Warwick took to the top ten in 1964 (his version ran over twelve minutes), and also on “One Woman,” a track recorded the previous year by the then-obscure vocalist Al Green; it was written by two of Memphis’s premier backing vocalists, Charlie Chalmers and Sandra Rhodes. The final song was a collaboration between Isaac and Al Bell with the fanciful title “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic.” Isaac explains, “We just wanted to tease people with all these syllables. The tune actually was talking about a beautiful affair that you had with this woman and you want an encore, a repeat.” The title may be barely pronounceable, but the music is propulsive and grooving. Multilayered, there’s tinkling piano notes on the high end, funky wah-wah guitar in the middle, and drumming on the low end that, just when its rhythm seems clear, defies expectations. Initially a challenge, the song trusts its audience, and sets off for territory not yet explored.

“Isaac was just cool as shit,” says Willie Hall. “He was a great person, energetic, didn’t do any drugs. He’d drink a little Lancers wine. And he would look up in the top of his head, the third eye, trying to come up with an idea—boom, it would come—perfect.”

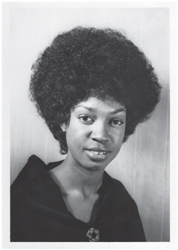

Deanie Parker’s birthday party, 1968. L–R: Cleotha Staples (rear), Deanie Parker, Pops Staples, Jo Bridges. (Deanie Parker Collection)

“When I finished the album,” Isaac remembers, “I played it for Jack Gibson—Jack the Rapper. He was a former DJ and a new Stax promotions man. And for Joe Medlin, the godfather of all promotions. I dragged them into the conference room and said, ‘I want you all to listen to something.’ When it was over they just sat there. ‘Well?’ I asked. One said, ‘Ike, I never heard anything like it in my life. It’s fantastic. But we don’t know about you getting airplay because it’s so long.’” But Isaac was seeking self-expression—he was leaving airplay to the other albums in the soul explosion.

![]()

Al’s vision of a total record company embraced the expanding multimedia world. Nothing was too big. For starters: television. He enlisted WNEW in New York as a partner, creating a one-hour TV concert that beamed from the antenna atop the Empire State Building to all of New York and beyond, and was syndicated in markets including Washington, DC, San Francisco, Memphis, and Los Angeles. “Gettin’ It All Together” featured Carla Thomas, Booker T. & the MG’s, and, in a final effort before parting, Sam and Dave. The set list of classic hits, a tribute to Otis Redding, and a group finale doing Motown were a calculated effort to reach a wide and new audience. “[The TV show] will introduce Stax artists to millions of new people and establish them as visual personalities,” Al proclaimed in the company’s new magazine, Stax Fax, its foray into the print medium. “The New York broadcast in April will also give our first major album release in May a terrific boost, and the subsequent prime-time broadcasts across the country will keep the excitement going.”

Stax Fax was a magazine that Al delegated to Deanie Parker in the autumn of 1968, directed toward both industry personnel and the popular audience. Filled with pictures, it kept Stax on the coffee table when it wasn’t on the turntable, and it quickly grew into a glossy format that included news stories germane to the contemporary African-American audience, opinion columns, and profiles on Stax artists and others, like Nina Simone and Florence Ballard, who were not associated with the label.

Busy with these big plans, Al needed an executive assistant, which he found in the African-American applicant Earlie Biles. She’d had training in secretarial science but knew nothing about the music business. “I was sitting there waiting,” she says of her job interview, “and in comes Isaac Hayes—with no shirt, some thongs, and some orange-and-purple shorts. He was the first baldheaded black man I’d ever seen. I was introduced to Johnny Baylor as a producer. He looked like the typical gangster you saw on television. He was kind of scary to me. Dino came in with him, and he was the second person I saw with a bald head. But Johnny was very nice to me—except one time. I stood up from my desk to greet him and he touched my leg. I slapped him, and then I got really scared because I realized I slapped this—what looked like a thug. He said, ‘Woo.’ And I said, ‘Don’t ever do that again.’ He said, ‘Okay, okay.’ And then a couple of weeks went by and he asked me to keep his gun for him. He wore kind of tight pants, and a short leather jacket, so I guess he couldn’t hide his gun. I don’t like guns, but I allowed him to put his gun in my drawer every time he came. And I learned to live with that.” Earlie was twenty-one years old.

Earlie Biles came to Stax in 1968. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

The feel and smell of success that permeated the new Stax was buttressed by the company’s friendly relations with its loan officer, Joe Harwell, who’d been working at the nearby branch of Union Planters National Bank since 1966. In the era of flower power and the burgeoning hippie movement, Joe was not your average straitlaced banker; not that he wore bell-bottoms and long hair, but he was comfortable around musicians and those whom mainstream society considered oddballs. “Mr. Harwell always did nice things for all the artists who would come in town,” says Earlie. “Johnnie Taylor or Don Davis, if they had no ID and needed checks cashed, I would just phone Joe Harwell.’ He supported all the Stax personnel very well.”

“Joe was this personable guy that would be right at home on a used car lot,” says one Stax employee. “He became a star at Union Planters. He would loan Stax a lot of money, and Stax would pay it back, and Harwell looked good. Whenever Stax needed money, he was ready for us.”

“I’d get on the phone to Joe Harwell,” says Duck. “‘Hey, it’s Duck. I’d like to buy my wife a car.’ Joe Harwell, he was so sweet. ‘What kind of car you want?’ ‘Cadillac!’ ‘You work for Stax? Okay, it’s done.’”

With friends like Joe Harwell, everyone could dress well, live in a nice home, and furnish it in the fashion of the day, driving to work in the car of their dreams. The songwriters for “Who’s Making Love” drove matching canary-yellow Cadillacs with black roofs. Al Jackson drove a blue Lincoln Continental Mark III. Steve was in a purple Buick Riviera (among other cars). Duck had a custom yellow Excalibur. The newly fenced parking area outside McLemore looked like a million-dollar car lot, a bouquet of gas-guzzling success.

Keyboardist Steve Leigh, then known as Sandy Kay, came to Stax in 1969 from New York, where he’d been playing with a group named the Soul Survivors. “Raymond Jackson [songwriter on ‘Who’s Making Love’] brought me over to see Joe Harwell, and I opened a bank account at Union Planters Bank on Bellevue,” he recalls. “Then Raymond brought me to a furniture store in Memphis, and with no more than his say-so, I had enough instant credit to buy thousands of dollars of furniture for the townhouse we rented. ‘You work at Stax?’ Presto! Credit! Just like that. The next day, all the furniture was delivered . . . A super king-size bed with the tufted velvet headboard and matching tufted velvet bench. It was exactly like Raymond’s, but ours was blue and Raymond’s was purple. Homer [Banks] had one, and Al Jackson did, too.”

It was boom time. “The city opened itself up to us,” says Willie Hall.

“You could borrow money if you wanted it,” says Earlie. “Joe Harwell, he was the fix-it-all for everybody.” By the time the soul explosion rolled around, everyone was living large.

![]()

If the soul exploding sales conference had been a symphony, it would have been Beethoven’s Ninth. It was a huge and glorious effort, interweaving the grand themes of salesmanship, civic responsibility, and the recording arts. It employed live performances, recordings, speeches, and a high-tech multiscreen slide show presentation with synchronized music. The future of Stax was riding on the success of the event. Its theme was, appropriately, “Gettin’ It All Together.” Had it failed, Gulf & Western would be hard-pressed to justify investing another cent in an organization that conceived such a folly. The company morale could not sustain a failure. Underlying the sales conference was the stark truth that this effort could sink them forever.

Stax booked all the meeting spaces at the city’s high-end Rivermont Hotel, overlooking the Mississippi River. Guests were greeted by klieg lights outside, and inside by Deanie Parker and her staff, who presented them with weekend schedules that included tours of the Stax studios. The first weekend, May 16–18, 1969, was dedicated to the distributors and sales agents from across the country—those wholesalers who could purchase the records and get them to the public. The following weekend, a one-two punch, was for members of the press and those who could urge the customer to purchase the Stax material, including the all-important “rack jobbers”—the companies that filled the Sears, Woolworth’s, and other non–music store racks with product. The rack jobbers reached the casual shopper who could be converted to an ardent fan. Great numbers of people were flown in at company expense. “We had Billboard and Record World and Cash Box,” says Deanie. “Rolling Stone was there, Playboy, Vanity Fair, Time, Jet, the New York Times. Representatives from BMI, from advertising agencies, publishing companies, and film production companies. Writers came from papers in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. We brought in a lot of the ethnic publications. And people came in from England. We did all of the right things right, and it was very, very impressive.” Artists performed their new material, including Booker T. & the MG’s, Carla Thomas, the Staple Singers, William Bell, Albert King, and new rock and roll signees the Knowbody Else (who would later become Black Oak Arkansas).

The albums that comprised the staggering twenty-eight featured many Stax stalwarts. The MG’s entry, The Booker T. Set, featured them interpreting eleven notable songs from the preceding year, from Sly Stone to the Beatles, the Doors to Herb Alpert. They’d been recently named Instrumental Group of the Year, 1968, by Billboard, and managed to squeeze in their own sessions while producing and backing other artists. “From the company’s perspective, the MG’s were meant to be the support band for Stax Records—always,” Booker explains. “The band would be allowed to make some singles and to have some solo success, but not to the point that we could become separate from the studio. The records weren’t given short shrift but the sessions and the opportunity to make the records were given short shrift. Booker T. & the MG’s, we just scratched the surface of what we could’ve done. The music we were able to do stands on its own and I’m extremely proud of it. I just think we could’ve done a lot more.”

Steve Cropper, left, speaks with Johnny Baylor at the May 1968 soul explosion sales meeting. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

The Bar-Kays cut their own album for the sales meeting, Gotta Groove. Ambitiously funky, they merged the traditional Stax instrumental with screaming rock and roll guitar, creating in songs like “Street Walker”—its blues harmonica dueling with the guitar’s edginess—a tune that wouldn’t be out of place on a Led Zeppelin album. Huge-sounding fuzz-guitar amps wail atop hard-driving drums. Their interpretation of the Beatles’ “Yesterday” is cubist and rich, thrilling in its breadth; an embrace of life’s possibilities. Booker says, “I thought the Bar-Kays were fully capable of taking over the Stax tradition.”

The goal of twenty-eight albums was missed by one: Though there was an album cover for Rufus Thomas’s May I Have Your Ticket, Please? there was no album inside—like getting a graduation envelope filled with a summer-school summons. Rufus was stung. There’d be no shindig were it not for Rufus Thomas and his family, less than a decade back and many a day since. His very spirit was woven into the company’s fabric. Since “Walking the Dog” in 1963, he’d been on and off the lower reaches of the charts (despite great efforts like “Willy Nilly”), and the company couldn’t manage to find time for finishing his record. But Rufus Thomas wore a frog costume on a Beale Street stage when he was five, and he’d been in showbiz long enough to know that if you kept them coming out, one would hit. He was the Clown Prince of Dance and the Funkiest Man Alive, and he remained professional all the way. He performed for the audiences, glad-handed the clients, and smiled his way through both weekends, despite the breach of faith. Instead of giving in to anger and resentment, he kept his eyes on the future. Indeed, he would soon demonstrate how much fun a third comeback could be.

The highlights of the convocation were the presentations. Each album was introduced with a multiscreen slide show, synchronized music, encouraging words from Jim and Al. With everyone gathered, Stax heralded its new emphasis on distribution, announcing a deal with soul star Jerry Butler and his Chicago-based company, Fountain Records. Interspersed among the business achievements were charitable announcements, including an educational program for the underprivileged called SAFEE—the Stax Association for Everybody’s Education. “The day care centers would be for children whose parents cannot afford to pay to send them to preschools or other centers,” Jim announced. “The trade school would furnish education for students through high school and for those who cannot afford to attend a college or university.”

The meeting’s keynote speaker was Julian Bond, who was then a state congressman in the Georgia House and a founding member of SNCC, for which he’d been communications director from 1961 to 1966. He hit strong notes of black separatism in his charged address, quoting a speech given 120 years earlier by the first African-American lawyer admitted to practice before the US Supreme Court, Dr. John S. Rock. But by the conclusion, Bond was establishing a broader platform for community activism, unifying the room as young people capable of implementing change. This speech was clearly not your typical music industry rhetoric of sales, markets, and profits. But Julian Bond was there because the Stax that Al Bell envisioned was not your typical music industry company. Stax, a new Stax, was on the rise.

Isaac Hayes.

One published estimate calculated Stax’s expenses for the two weekends at a quarter million dollars. “It was awesome,” remembers Al. “And like Atlantic, we had the sales forms there and the purchase orders and our wholesalers left purchasing product”—$2 million worth of product, according to Billboard. “With those twenty-seven albums at one time, folk began to forget that we didn’t have a catalog. Out of that meeting was born Mavis as an individual artist, Isaac Hayes as a giant, and on and on. We came back from the dead not with the vintage Stax sound of Otis Redding and Sam and Dave. We came now as a diversified new company. And that positioned us in the record industry as a viable independent record company. It accelerated from that point forward.”