Isaac Hayes shot to fame like an express elevator to the penthouse floor. He released two albums in 1970, The Isaac Hayes Movement and To Be Continued, each built like Hot Buttered Soul—two songs on each side, with Ike’s extended, intimate raps gliding listeners into his velvety world. Both raced up the charts.

The Isaac Hayes Movement came out in March and spent six weeks at the number-one spot on the soul chart; it stayed on the chart nearly the whole rest of the year, falling off just in time for the December release of To Be Continued, which ran to the top. Movement spent a year and a half on the Billboard 200 album chart and featured a version of the Jerry Butler song “I Stand Accused” as its single, which proved popular among both soul and pop audiences. The album art finds Isaac relishing his newfound star status. The cover opens to reveal a vertical centerfold of Isaac, shirtless, wearing thick gold chains around his neck and waist. His arms are forward and down, as if he’s lifting something, or someone. The lighting is dramatic, he’s wearing dark shades, and it’s all so supercool that it trumps the back cover shot of him seated, draped in a matching multilayered zebra-striped outfit with a high collar and zebra cap. Isaac Hayes, song interpreter. Mellow and mature, intimate and warm. Dance? The horizontal dance, ma cherie. The next album, To Be Continued, hit the top of the soul and jazz album charts, and fell just shy of the pop top ten. “Isaac became a major artist, selling gold, then platinum, and double platinum,” says his drummer Willie Hall. “Everywhere you went, you’d read about Isaac. You turn the radio on, every station, you’d hear his material. It was wonderful. Everybody had money to spend. I managed to take my family out of the ghetto and buy our first home. Things were really good.”

Though Isaac had established himself first as a songwriter, none of these three albums featured any of his own songs. (He’d cowritten “Hyperbolic . . . ” and by To Be Continued, he’d begun naming his long introductions, which allowed him to collect a publishing royalty on them.) The lack of original material followed the termination of his songwriting partnership—Isaac had always taken care of the music, David handled the lyrics. Without David, Isaac could maneuver other people’s words, he could rearrange established hits—but he wasn’t writing new songs. “I try to express myself in music,” he told a journalist in 1970, putting a positive spin on it. “I generally prefer to do covers of other songs. I like to change the arrangement and do big productions, taking the songs into a completely different world.”

Another world was, in fact, opening up for Isaac. The MGM movie studio was facing a slump at the box office, and before bellying up, they were willing to take inexpensive gambles, such as throwing half a million dollars at a movie that could wring a few bucks from the neglected African-American audience. The recent release of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, saturated in black pride, had summoned an untapped market demographic. It opened with text on screen: “This film is dedicated to all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the Man.” Filmmaker Melvin Van Peebles had funded and made the show himself, producing, directing, editing, and starring—among other roles. When the Chicago band Earth, Wind & Fire recorded the soundtrack, they had yet to release their first album and were totally unknown. With no promotion budget, Van Peebles approached Stax about pre-releasing the soundtrack; their promotional prowess in the black community was established, and he knew that a soundtrack would readily appeal to the company’s expansive nature. (Additionally, vocalist Maurice White was from the same Memphis housing project where David Porter had grown up, so he had an in.) Three months after Stax’s album release, the movie premiered. In addition to its sex scenes, part of the movie’s appeal is that Sweetback survives the Man’s manhunt—he outsmarts Whitey and escapes. As word spread, big crowds came to the theaters. Stax was ahead of that game; Al Bell arranged with the Detroit theater owner where it first screened to sell the soundtrack in the lobby, and he shipped three hundred albums. More were ordered the next day. “Many theater owners were hesitant about our suggestions to make albums available in the lobbies,” says Al, “until they discovered how profitable it could be.”

When MGM was designing its African-American pitch for Shaft, it too reached out to Stax. Isaac recalls MGM’s concept: “A movie targeted at the black consumer market to have a black director, black leading actor, black editor, black composer. And I was asked to do the music.” He’d always wanted to be on the screen, and this role seemed right for him: “A private dick who’s a sex machine to all the chicks,” as Isaac would soon write in the theme song. He said he’d commit to the music if he were allowed a screen audition. Isaac soon learned that the lead had gone to Richard Roundtree, a model who’d become prominent touring with the Fashion Fair promoted by Ebony magazine. The twenty-eight-year-old Hayes expressed his disappointment—but agreed to honor his musical commitment.

Some weeks later, the director Gordon Parks called. Parks was a revered fashion photographer, known also for turning his camera—still pictures and film—on African-American life. Shaft was his foray into bigger movies. He told Isaac he was sending him a few scenes to score. No one called them a test, but Isaac knew that if he didn’t get it right, the job would vanish. “Gordon Parks knew I’d never done a soundtrack so they handled me with kid gloves,” he says. “And I appreciated that. Gordon said to me, ‘Shaft is always roving, always moving. Your music should depict that—something to capture his personality. His being. He’s a cool dude too. But he’s tough. You got to put all that in your music.’”

Willie Hall recalls being introduced to the project. “We’re in the studio recording with Isaac,” Willie says of the Bar-Kays. “We’d work through the night, and Isaac’s in and out of the studio constantly—taking phone calls, doing business. Isaac even had a phone in his car—back when that took up nearly all of his trunk. He comes back from a break, and he and Al Bell wheeled this machine in. They didn’t have the big video screen back then, so we all were squeezed in, trying to look in this little machine that you could see the footage through [a Moviola]. Everything was hush-hush and we see Richard Roundtree coming up out of the subway, walking down Broadway. Isaac said, ‘I got a surprise for you all. We’re gonna do a soundtrack to this movie.’ Everybody went, ‘Wow’—but we have no clue of what the procedure is gonna be.” Lester Snell, keyboardist, remembers that the next question by all was, “How much will we get paid?”

Hayes was ready for the challenge. Soundtracks worked toward his strength—music and drama; he’d not need a lyricist. He told Willie to note the tempo of the characters walking. “He said, ‘I want you to play sixteenths on the high hat to that tempo,’” Willie continues. “So they rolled the machine over to me, and I play the high hat. The tempo of his steps is where we got the tempo of the song from.” Hall begins making the cymbal sounds, the classic cymbal sounds, that open the Shaft theme song.

They set to work. The title theme’s trademark wah-wah guitar sound was accidental. “When I play rhythm, I will put a lot of drum beats with it,” says guitarist Charles “Skip” Pitts. For Shaft, “I was checking my pedals. I tested my overdrive, my reverb, the Maestro box, and then I started in with the wah-wah. Isaac stopped everything and said, ‘Skip, what is that you’re playing?’ I said, ‘I’m just tuning up.’ He said, ‘Keep playing that G octave.’” Set to Willie’s sixteenth notes, they had the makings of something good.

“Within two hours we had the arrangement for the main title,” says Isaac. “The next piece of footage was the montage through Harlem. Did the music to that in about an hour and a half. It would become ‘Soulsville.’ The third piece was the love scene. I wrote that in about an hour, which later became ‘Ellie’s Love Theme.’” Isaac flew to New York, to Gordon Parks’s East Side apartment overlooking the UN headquarters. “I had the tapes under my arm. Gordon was cooking some lamb chops, man it smelled so good in there. And he teased me because I liked apple butter instead of mint jelly with lamb chops. I’m a country boy, what do you want?” After dining, they put the footage on the Moviola and the tapes on the deck. Gordon watched. “He said, ‘Okay, you can go to Hollywood now and start on the film.’ Just like that.”

It was a learning experience for everybody. Excited, their lack of experience fed their innovation.

“We were gigging every weekend on the East Coast,” says Lester Snell. “We’d fly east and gig Friday, Saturday, Sunday, fly back Sunday night to be on set Monday morning. MGM put us on a schedule: Be on set at nine and work till five every afternoon. Just like a job. We had six weeks to do the movie—compose fifteen songs, rehearse them, lay out according to soundtrack, and then record. And still gig on weekends. It was a killer.”

“That whole adventure was exciting,” says Willie. “Skip and Michael and myself, we used to get in trouble on the studio lot because they had these bicycles you use to get from one area to the other. We’d be turning the corner, we’re running over folks, man, people in costumes would be falling, they’d call and report us. ‘Hey, man, you got to keep those niggers out of the way, they’re running over everybody.’ But we had a lot of fun and they loved us.”

Gordon Parks stayed abreast of their progress. In a “making of Shaft” short movie, Parks, chewing a toothpick, listens intently as they play him a draft of the title song. “When Shaft pops up out of that subway,” Parks tells Isaac, “that’s when it should really come on and carry him all the way through Times Square right to his first encounter with a newspaperman. And that should be a driving, savage beat so we’re right with him all the time.”

When the recording dates arrived, it was a collision of cultures. “They set aside four days for us,” Isaac explains. “The first two days was for the rhythm, the third was for the sweetening—horns, strings, all the miscellaneous instruments, and the fourth day was for vocals. So we walked on the soundstage, they had our music stands set up and everything. We’re getting comfortable and the engineer said, ‘Where are your charts?’ ‘What charts? We ain’t got no charts, man.’ ‘You don’t have charts!’ I saw terror in this man’s eyes. I said, ‘Just roll the film, man.’ Everybody had their own little private notes that they’d written down. This is head-arranging at its finest! Guy rolled the film, the swipe went across the screen, the first music cue came, bam! We hit it. I called, ‘Next!’ We played reel after reel. Next cue. Next cue. And we knocked ’em out. That first day we finished an hour and ten minutes ahead of schedule and had done both days work. The engineer said, ‘I have to tell you guys I thought this was going to be a disaster. How’d you guys remember all that with no charts?’ I says, ‘We work in a studio, man. We’ve been doing this for years.’”

“We recorded the whole thing in three days,” says Lester Snell. “They were amazed we could do it that quick, because they really didn’t believe we could do it at all.”

On the third and final day, Isaac was being driven to work with his three beautiful backup singers. Much as he wanted to concentrate on them, he was distracted; he’d just learned that for a song to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Song, it needed lyrics. So he soaked in their vibe as he jotted the song’s conversational lyrics on a piece of paper, not quite done even as they entered the lot. “Who is the man . . . Just talking ’bout Shaft . . .”

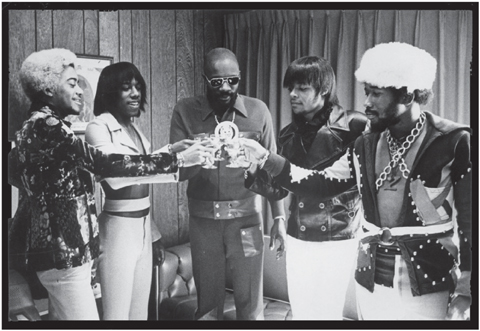

Isaac Hayes, backstage, with some of the Bar–Kays. L–R: Harvey Henderson, Winston Stewart, Isaac Hayes, Larry Dodson, James Alexander.

Everyone was excited by the results. But the standards in Hollywood were different from the standards in Memphis; MGM was a film-score factory, and this project was a low-budget toss-off. Isaac and the Bar-Kays—they were making art. MGM used what it paid for in the film, but when they returned to Memphis, Isaac and the Bar-Kays re-recorded the whole thing at Stax. The musical performances are better, the fidelity is higher, the arrangements are tighter. When inclined, Isaac extended a song longer than what the movie called for—he’d made MGM’s soundtrack, now he was making his record.

And soon he’d be setting new records, as the Shaft album, released with the movie in July 1971, became his most successful album in a string of highly successful releases. It won three Grammy Awards and took home an Oscar for Best Music—Original Song. The album—the double album—became Stax’s best-selling album ever and helped the film recoup more than twenty-six times its investment. At the Academy Awards ceremony, Isaac—a ladies’ man, sex symbol, and now pop star—brought as his date the woman who was the most significant in his life: his grandmother who had raised him. He performed the theme song on the telecast, and then returned to her side to await the award announcement. “My grandmother was cool, but I was trembling,” he told Ebony magazine. “I felt an enormous weight on my shoulders. There was a lot riding on that Oscar—not so much for me as for the brothers across the country. I didn’t want to let them down.”

After his success, other popular black musicians were offered film scores, including Curtis Mayfield (Superfly), Marvin Gaye (Trouble Man), Donny Hathaway (Come Back Charleston Blue), Willie Hutch (The Mack), James Brown (Black Caesar), and Bobby Womack (Across 110th Street). “A major film with a black director, a black star and sound by a black composer is an enormous source of pride to the black community,” Al Bell told Billboard. “Since music is usually an integral part of these movies, soundtrack albums have a ready-made market if you know how to reach the people.” Having converted theater lobbies to record stores, Al knew how to reach people.

Most important, the soundtrack was an expansion of Isaac’s palette. His three prior albums had adhered to the same formula, and by the third, the formula was becoming stale; they seemed redundant, self-indulgent. The nearly twelve-minute version of “The Look of Love” from To Be Continued, originally recorded by Dusty Springfield in 1967, finds Isaac losing himself to heavily reverberating moans and grunts. (Granted, however, that the instrumental section of the song has been heavily sampled.) But Shaft featured all original material in a new and totally different direction, and indicated a giant step forward in his art and career. Shaft relied on new sounds—the wah-wah—and it shifted to rhythms more aggressive than those emanating from the black church, essentially demarcating the end of the southern soul era and establishing a gateway to 1970s funk.

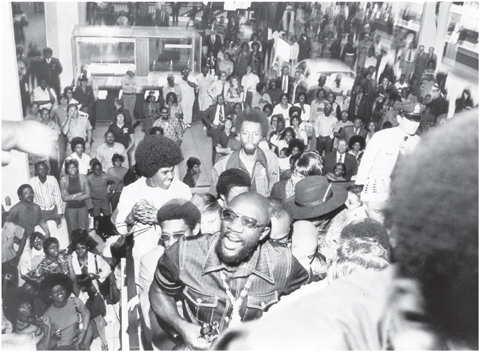

Isaac Hayes in the lobby of the Memphis airport, returning from the Academy Awards, Oscar in hand. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

![]()

A few months after Shaft’s release, the racial conflict in Memphis broke wide open. There were four days of rioting, three deaths, untold injuries, arson, and looting. The fury began with a pickup truck driver afraid to stop for the police. Three African-American friends led police and sheriff’s deputies on a high-speed chase. When captured at a roadblock, seventeen-year-old Elton Hayes (no relation to Isaac) was beaten to death by eight policemen and sheriff’s deputies. (One of the deputies was African-American.) The police announced the teen was killed when his truck overturned, but the morning paper ran a photo of the truck showing no significant damage; an autopsy revealed his skull had been crushed. His friends told of police beating them with billy clubs, and described Elton’s face when he was placed on a stretcher as looking like red Jell-O.

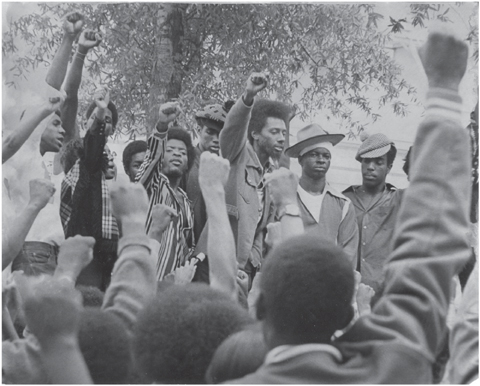

October 1971, anger over the killing of Elton Hayes. Sweet Willie Wine, center, with beard, leader of the black militant group the Invaders, rallies a crowd. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

The fatal beating and the attempted cover-up led to four days of rampaging violence and destruction across the city. “These officers are riding the streets like it was duck hunting season and they were enjoying it,” Isaac Hayes complained in the city’s largest newspaper. “They’re tearing down everything we are building.”

Isaac, along with Deanie Parker, Rufus Thomas, James Alexander, and several others from Stax, was among the community leaders who met with Mayor Loeb and then took to the streets and the airwaves (WDIA) to restore order. After the meeting, Isaac said, “A miracle has happened in Memphis. The mayor and chief of police have joined with the black community.” A curfew for the night was lifted and a benefit at the Mid-South Coliseum featuring Isaac was allowed to proceed.

The state attorney general promised a full investigation. Indeed, eight of the police and deputies were indicted, but the trial was another meeting of the good ole boys’ club; all were acquitted.

As one trial ended, another began, this time in the schools. An April 1971 Supreme Court ruling (Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education) led to what opponents termed “forced busing,” the transporting of black and white kids from their neighborhoods to schools across town. The object: to achieve a racial balance in student bodies and a semblance of fairness in accessibility to facilities.

White Memphis was angry, afraid, and defiant. In response to busing, a coalition formed, Citizens Against Busing. They held rallies and whipped up dissent. CAB, as the group became known, set out not only to stop busing but also to pass a constitutional amendment prohibiting federal court jurisdiction over public schools and to establish staggered terms for Supreme Court justices. Henry Loeb and Wyeth Chandler (who would succeed Loeb as mayor) were among the politicians supporting the group, with Loeb calling busing “reprehensible” and Chandler calling it “monstrous.” State and federal congressmen joined CAB’s rallies; a Tennessee senator in Washington, DC, took up older legislation that “would guarantee the rights of all children to full and equal access to neighborhood schools without being treated as members of a race.” The senator did not add that the schools in the CAB neighborhoods were solid, and the schools in the black neighborhoods were crumbling. Many of the black schools had leaky roofs, unstable stairs, missing windows, and other structural deficiencies; few, if any, had air-conditioning. Such institutional disparity and legislated unfairness had long existed. Racially restrictive residential covenants—“no blacks allowed” in certain neighborhoods—had been Memphis law and enforced until early 1970, two years after the Fair Housing Act made such covenants illegal, more than twenty years since the Supreme Court said they were unconstitutional.

The school desegregation fight was making it evident that the majority of white Memphians clung to these discriminatory beliefs, proudly. Calm was restored after Elton Hayes’s killing, but the tension over busing was just beginning.

![]()

Stax was a sanctuary from the pervading hostility, but also a war room for its own ongoing expansion. The broad demand for Shaft opened doors through which Al Bell could ship other albums, increasing his access to the white market. The nearby Ardent Studios, where Stax sent much of its overflow work, was restarting its own label, Ardent Records, and Stax agreed to distribute them. Ardent had a promising young power pop band, Big Star, and Stax wanted to establish them nationally. “We were ginning money at that time,” says Al. “We had hit records—like great apples falling off a tree. And we were selling albums—the albums were generating more revenue than the singles. We’d sell a hundred thousand albums on an artist, which wasn’t much to some companies, but we’d sell hundred thousand after hundred thousand after hundred thousand. That’s serious cash flow.”

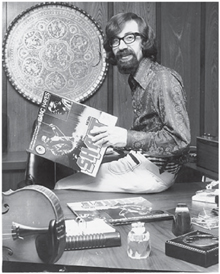

Just talkin’ ’bout . . . Jim Stewart, with Shaft album and mandala, 1972. (Photograph by Tom Busler/Commercial Appeal)

The Bar-Kays remained consistent sellers and also consistent innovators. Their post-Otis incarnation—Bar-Kays Mach II, as they sometimes called themselves—always had a theatrical flair: Onstage they moved with coordinated chaos, ready for a party; their outfits were out there on an Isaac Hayes orbit; their music was brash, careering through styles, with dynamic changes that could propel a dance floor. Their 1971 album Black Rock opens with a nearly nine-minute interpretation of Aretha Franklin’s “Baby I Love You.” They filter it through Jimi Hendrix, but with soul horns. They remake Isaac and David’s Sam and Dave hit “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” playing it like one of the aggressively cross-fertilizing late-sixties California bands—maybe Spirit or Moby Grape—part hippies, part jazz cats, part hard rockers. The single “Montego Bay” didn’t chart, but the album did. A Bar-Kays album is like flipping a radio dial, landing only on the best songs.

The Bar-Kays weren’t the only successes. Since the start of 1971, Stax had placed another wallop of chart singles—Isaac Hayes’s edited version of “The Look of Love” and his “Never Can Say Goodbye,” the Emotions’ “You Make Me Want to Love You,” Margie Joseph’s “Stop! In the Name of Love,” Johnnie Taylor’s “I Don’t Wanna Lose You” and “Hijackin’ Love,” the Staple Singers’ “You’ve Got to Earn It,” Rufus Thomas’s “The World Is Round” and “The Breakdown,” and the Newcomers’ “Pin the Tail on the Donkey”—all these before summer was over.

So Al Bell had reason to be emboldened. He was achieving these huge sales with a distribution system that he, his salesmen, and marketers had built by themselves. It was independent distributors working with independent record companies, following independent rules. “Al Bell was a visionary,” says James Douglass, one of several young salesmen hired by Al to fan out across the US and promote records. Al made sure his team was groomed, dressed in a jacket and tie, and he trained them in the basics of respectfulness. “‘Yes sir,’ ‘no sir,’ stand until they ask you to sit,” James explains. He had no background in the music industry and remembers his training in promotions as quite basic: “Al would have four, five, six releases for us to take out. Hopefully there’d be an Isaac Hayes in there. Al would present the records to the promotions guys, suggesting where they might be hot because of similar action there. I began to set up appointments with DJs to tell them about our product. Al used this word, defuse. He’d say, ‘Defuse any situation out there.’”

The situations that needed defusing usually concerned money. “I go to some big DJ with several records and he says, ‘I like this one here, can I get into it?’” James explains. New to the game, he wasn’t immediately sure what was being asked. “I said, ‘Into it, like what?’ He tells me, ‘See the distributor and he’ll tell you.’ I know if I go back to Al, he’s going to say, ‘Defuse it. Figure out the cracks, and figure out how to stuff the cracks.’ I realized going to the independent distributor was the thing to do. He might say, ‘When Stax mails in the next batch of records, tell them a station is doing a Stax weekend. Send me extras, but don’t drill ’em.’” Promotional records were differentiated from commercial stock by a drill hole in the album cover’s corner; shipping not-drilled records that were indicated on the paperwork as promotional was as good as cash for the distributor. “We’d ship in so much above what they order, and they’d give extra to the DJ and my hands stayed clean,” James explains. The slush money, in other words, was covered by product that the distributor could sell at full price, and that the supplier—Stax—could write off as promotional. A DJ could receive them free and wholesale them to a store; a distributor could make a profit on them that might cover a loan they’d made on Stax’s behalf. “Promotional” records with no drill holes allowed for creative accounting.

As the 1970s progressed, the record business got ever more crooked, harking back to the days of pay-for-play. “I wouldn’t give DJs money,” James says, “but if I were filling my gas tank, I’d fill theirs too. If we ate together, I’d buy. With my expense money, I’d take the DJ’s wife to the grocery store. Al said, ‘It’s not payola, it’s pride-ola.’ They changed the name of our job to marketing. We didn’t do no marketing. Promotion guys are promoting money. One station ran a Miss Black pageant. The guy couldn’t meet payments, asked me to call Al. If I did, I knew Earlie would say, ‘Mr. Bell don’t have time to deal with that kind of mess.’ I went to the independent distributor. Defuse it.”

In early 1972, a Washington Post investigative reporter, Jack Anderson, exposed “the gangster-like world” in which James Douglass was finding himself immersed. NEW DISC JOCKEY PAYOLA UNCOVERED was the headline, and the series of articles documented how radio personnel “across the country are provided with free vacations, prostitutes, cash and cars as payoffs for song plugging.” In other words, disc jockeys would play your records more often if you compensated them. (Soon, some wouldn’t play your record unless you paid them.) The investigation revealed that record companies, large and small, indies and majors, “furnished wholesale lots of free records to so-called ‘R&B’ jockeys and programmers. They, in turn, sell the records cut-rate to record stores, pocket the profit and boom their benefactors’ records over the airwaves.” The issue—as always—was the money and how to hide it. Record retail was largely a cash business, and following the money becomes increasingly difficult, especially because promotional records often substituted for cash.

Anderson’s next headline dug deeper: DISC JOCKEY PLAY-FOR-DRUGS OUTLINED. Some of the record companies were digging into deeper nether-worlds. James Douglass remembers the first time he saw cocaine, which was making its way onto the American street in the early 1970s. He’d been working his way into larger markets and was visiting a distributor in Philadelphia. “I knock. ‘Who the fuck is it?’ ‘James Douglass from Stax.’ ‘Come on in, shut the door.’” James entered and sat across from the program director. “I’d never seen a rock of cocaine before,” James continues. “He had a razor blade and he was shaving off of it. Another record company’s promotion guy had just left. ‘Did Al send me anything?’ ‘No sir.’ ‘You’re new. You been to the record shops yet?’ ‘No sir.’ ‘Get your ass down there, work them record shops, when you got product in the market, come back and let me know, I’ll bust all your records.’” Things were getting ever more complicated. The night DJ saw the better clothes that the daytime DJ wore, or the bigger car that the distributor drove; everyone’s demands rose. “Man,” sighs James, “I just came to represent the company.”

Distribution was a circuitous and rickety operation that had been thriving for years when Anderson exposed its crookedness; despite its effectiveness, it left Al dissatisfied. “The product was not getting into the larger stores that catered primarily to whites,” he says, “and I became very aggressive and demanding with respect to that.” He conceived a venture in the Chicago market that was not only about the sales it would achieve, but also about documenting those sales. Al’s broad vision encompassed the meta-view; he would create a presentation about the success of the Chicago campaign that he could use to wedge his way into other prominent markets. Thus was born the Stax Sound in Chi-Town, a promotion in August 1971 (a month after Shaft hit theaters) that coordinated with the Sears home office and the many Sears stores in the Chicago area. “They put our entire catalog in all of their stores, and we came in with an advertising and marketing campaign—print, television, and radio,” says Al. “We even hired some beautiful models and had them in front of all of the Sears stores wearing the little sash that Miss America wears, and it said STAX SOUND IN CHI-TOWN.”

Chicago was not a random choice. The Great Migration had moved a huge population of southern black people to Chicago since the early 1900s; blues had begun in the Mississippi Delta (all roads there lead to Memphis) and become electric in Chicago. The cultures were related. As well, Chicago was home to Jesse Jackson’s Operation PUSH, and since their meeting soon after Dr. King’s assassination, Al and Rev. Jackson had grown increasingly close, a vision shared. The previous year, Al even initiated a new subsidiary, the Respect label, to release Rev. Jackson’s first album, I Am Somebody, which included his outstanding title-track sermon and incantation Respect would soon add other spoken-word-oriented releases. The Chicago ties were many. “As it turned out,” Al says, “one of my homeboys, E. Rodney Jones, born in Arkansas like me, was at Chicago radio station WVON. I had a deep relationship with several other great personality jocks there, and it dawned on me, instead of us going all over the place trying to get things done, let’s build a base in Chicago. Let’s get more involved with Johnson Publications [Ebony, Jet] and Operation PUSH—deal with Chicago like we’re in Chicago.”

Stax began sending talent—Isaac Hayes, the Staple Singers, and seven others—to the Operation PUSH Chicago Black Expo, a trade show and convention. Their performances were filmed, and thus able to be exploited long after the applause died down. “Al Bell never was just the record guy,” says Rev. Jackson. “Al saw the vision. Many people see our artists through a keyhole, Al saw them through a door.”

Al understood the moment—any moment—as a piece in an ever-expanding puzzle; the more assiduously he tried to see the limits, the bigger he knew the puzzle could get. While the success of Stax Sound in Chi-Town would prove the broad commercial potential of his label and result in increased sales, its long-term use would be through its repurposing. He hired an agency to professionally document the program and its results, creating an elaborately bound presentation. Was this a beautiful package to lie on the coffee table for guests waiting in his office? No. The images became slides accompanying his speech entitled “Black Is Beautiful . . . Business.” He would soon present the speech at the 1972 National Association of Recording Merchandisers convention, where it became a powerful statement about the drive and success of an independent company.

Stax in Chicago. L–R: Jim Stewart, Jesse Jackson, Lydia Bell, Al Bell, Emily Hayes, Isaac Hayes. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

After Al fit Chicago onto his expanding puzzle, he looked for more pieces. “We were able to move out from Chicago toward New York and Los Angeles and surrounding geographic areas,” Al waxes. “We were looking toward getting into the state of New York—actually that triangle of New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. We’d captured the mid-Atlantic, which was Washington, DC, Virginia, and Maryland. We knew Rocky G and Frankie Crocker at WWRL in New York, and if we could get our artists into the Apollo, we could capture New York, meaning not just radio, but the consumers in New York. It was generally known in the industry that Los Angeles is gonna be the last place where you can get your product exposed.” No worries: Al was cooking up a blockbuster-sized idea for Los Angeles.

![]()

On the home front, a new problem had arisen. Deutsche Grammophon, which owned a piece of Stax, was so enjoying its taste of popular music that it wanted more. In mid-1971, the label purchased James Brown’s recording contract and back catalog. Between James Brown and Stax, all they saw was hits and high sales, so they instigated an expansion of their own label, Polydor. “They began to want to exercise some influence on us and on our business decisions,” says Al. “And the discussions arose once again about us consolidating our distribution.” Stax had an interconnected web of independent distributors that Deutsche Grammophon saw as a peculiar and clunky arrangement. Despite the setup’s obvious success, Deutsche Grammophon wanted to align Stax with a corporate distributor. While a corporate distributor might help Al get into the chains he sought, he feared losing the control he currently had; putting Deutsche Grammophon between himself and the product delivery created too great a distance. “The relationship,” says Al, “grew uncomfortable.”

“I told them that we wanted out of the deal,” Al continues, “and they were irritated by that. The audacity! ‘You little old fella from Memphis backwater Tennessee’—Philips, which owned Deutsche Grammophon, controlled the sockets that the light bulbs went in, and the energy throughout your home, so—‘who do you think you are?’” Extended conversations ensued—“Somewhere in there I may have become an irritant, because of my persistence”—and finally Al was given a number: It would cost $4.8 million to buy back Deutsche Grammophon’s equity in Stax. “Nearly half of that came from cash that we had in the bank, and the other came from a $2.5 million loan from Union Planters Bank,” says Al. Union Planters National Bank had helped them buy back their stock from Gulf & Western; payoff had gone very smoothly—ahead of schedule, even—so acquiring the new loan was easy.

The deal was settled that cool November of 1971 in the back bungalows of the Beverly Hills Hotel. “I walked rather proudly through the Polo Lounge,” says Al, “and on back to the bungalows. And I politely put that cashier’s check on the table and closed that deal with the gentleman, freeing us from the international distribution as well as purchasing back their equity interest in the company.” Stax’s 1971 gross income, according to court documents, was just short of $17 million. That’s a heap of sales accumulated at wholesale rates of about fifty cents per single and $2.50 for albums. Stax was, for the first time since it had become a national concern, entirely independent, able to determine its destiny, keep its profits, set its own course.