Isaac Hayes, with his fourth hit album in a row, was fueling the Stax inferno. That November of 1971 when Stax paid off Deutsche Grammophon, the “Shaft” single hit number one on the pop charts. Shaft raged across the US—in theaters, on turntables, as a cultural phenomenon. Isaac was on daytime TV, nighttime TV—fashion talk, movie talk, music. His clothes, his chains, his bald head, his female dancer’s bald head, the traveling orchestra: He was a phenomenon.

In Isaac’s camp, in Isaac’s glow, was his penumbra, Johnny Baylor. A heat radiated between them until that heat became a fever, a fever dream, and then a nightmare. “It got kind of rough around there,” says Willie Hall. “There was pistol play, there were shots being fired in the building.” At Stax, Baylor was running Isaac’s camp, his words always in Isaac’s ear. Baylor’s artist, Luther Ingram, was opening for Isaac’s concerts, using Isaac’s band and singing in a style not dissimilar; Johnny even signed Isaac’s shaved-headed female dancer, Helen Washington, to his Koko label. Johnny’s key responsibility was handling Isaac’s money, and when an important week of gigs at the Apollo came up short, there was nearly a bloodbath in the halls of Stax.

“When Shaft was coming out,” Randy Stewart explains, “I went to New York, made a deal at the Apollo Theater. The money would be split seventy-thirty for us, because they couldn’t have guaranteed us what we needed. While I was there, I had another meeting. We took ten thousand dollars and put it somewhere so Shaft would be number one when we got to New York City.” They bought airplay and ratings, he’s saying, so they’d be able to sell out all of their shows. It wasn’t legal, but it was par for the day, industry-wide, and it worked. It was how you got records played.

“At the Apollo, we filled every seat in there every day for a week, several times a day,” Randy continues. “Isaac was looking for big money.” But when Dino brought the Apollo payment to Isaac, it seemed light. Trouble had been brewing anyway—Johnny was intense company and Isaac wanted some air. He accused Johnny of bringing him short pay. “I know they hadn’t stolen the money,” says Randy. “We paid Luther nine thousand dollars as opening act, ten thousand went for the number one at the radio station. I had papers to show Isaac.” But this split, once begun, couldn’t be stopped. “When we got back home,” says Randy, “Isaac said that Johnny had stolen his money.”

Dino remembers the incident, and believes Isaac was misled. “Some of Isaac’s friends had misquoted some figures to Isaac,” says Dino, “and he felt that something was going wrong with the financing. But certain people wanted Johnny out, because they wanted that position that Johnny had with Isaac. And to get that position next to Isaac, they had to, boom, come up with something that wasn’t really true. And that put a space between Johnny and Isaac.” Baylor didn’t take such accusations well, and neither did he intend to simply walk away, or be pushed, from a star he felt he’d created. Baylor was top gun, and he was angry.

Mickey Gregory, who’d grown up with Isaac and, in addition to playing trumpet for him, had always been a trusted player in Isaac’s organization, was looking out for his old friend. “I was never one of Dr. King’s nonviolent Negroes,” says Mickey. “I was the only one with the exception of Isaac that the sheriff’s department would give a permit to tote a pistol—though I wasn’t the only one toting a pistol.” Mickey was tipped off by a woman friend whom Isaac had dated, now keeping company with Johnny, that Johnny was going to come to Stax with guns and that he intended to keep his job. “She gave me a vague warning that something was going to go down at the studio,” says Mickey. “I didn’t know if Johnny was supposed to kill Isaac, kidnap him, whup him, or whatever. But I did know that he was coming to the studio to do something, and I had that situation covered. I was in a beauty shop across McLemore from his office with an AR-15 [semi-automatic rifle]. I had the guards positioned. Everybody was doing whatever the fuck I said to. Wasn’t nothing going to happen—to Isaac.”

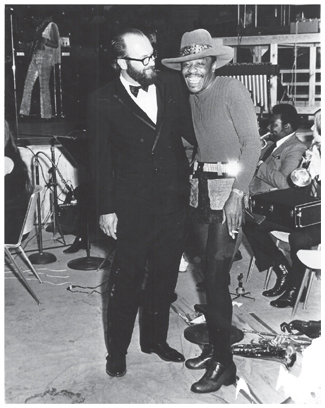

Isaac Hayes’s trumpet player and childhood friend Mickey Gregory, right, early 1970s, with a Houston concert promoter. (Mickey Gregory Collection)

“The night before,” says engineer Larry Nix, “I was working late in the copy room, making a little overtime. It was very unusual because there was nobody in the building. Every hour the guard would come through. Just me and him. The next morning I’m in studio A and everybody’s talking to each other, asking, ‘What went on?’ It turned out that nobody worked because they’d heard the Johnny Baylor confrontation with Isaac was supposed to go down then. I didn’t know because I always steered waaay clear of Johnny Baylor.” Just as people were sighing with relief, the security guard rushed into the studio and told them to lock the door, that Baylor was on the lot. “I took off to tell my wife, who was working in the publishing office,” Larry continues. “When I crossed the hall, I looked down and there’s Isaac’s guys on one side of the wall, Johnny’s guys on the other, staring at each other. You could hear Isaac and Johnny going at it in Isaac’s office. Johnny’s saying, ‘You can’t fire me!’ And it was loud, you could hear them all over the building. I closed the door in the publishing office and I’m thinking how the walls are so temporary, if someone shoots, it’ll go from one end of the building to the other.”

In more than one account, each camp had guns drawn on the other, or at the ready, and the mess about to be made would require more than just the night janitors to clean up. The confrontation in Isaac’s office got so bad, the threats so loud and so harsh, that someone, elsewhere in the building, called the police. Isaac’s office had a door that opened onto McLemore, and that’s where the police came. “The cops arrived outside,” Larry continues, “and all at once Isaac’s hallway door flies open. There were sawed-off shotguns, pistols, and these guys were stuffing them everywhere.” Isaac didn’t invite the cops in, but he came to the door, showed that he was all right, and admitted that there was indeed an argument going on but that it was a “family discussion.” He put the cops at their ease, and they left. Isaac could have ratted out Baylor then and there; if he’d let the cops in, they’d have found guns, they might have found other illegalities—but Isaac protected Baylor, defused the situation.

“They stuck them pistols up there in different places before talking to the police,” says Randy Stewart. “Police came, Isaac lied, said ain’t nothing wrong. The police left. Johnny took a records box, put the pistols in there, sealed it up like a box of records, had me take it to Johnny’s girl’s house. I walked right on by the police with that records box. That was the end of that, and that was the end of Johnny and Isaac. It was all over between them.”

While Johnny Baylor was very effective in increasing Stax’s debt collection, and thereby its cash flow, every victory was also a loss of power from elsewhere, from Al or Jim. Was Johnny Baylor good to have around? Did the benefits outweigh the detriments? The showdown in Isaac’s office, the threat of guns so close to—pointed at—the company’s biggest star, one might conclude this is an opportunity for reassessment, for termination of the relationship. A threat to slay the company’s star moneymaker should be the last threat before an employee is shown the door.

Not strongman Johnny Baylor. In 1972 in Memphis, Tennessee, at Stax Records, following an armed in-office showdown, Johnny Baylor was promoted. Instead of dismissing him, Al Bell assigned him to the promotions department, to the job of raising the company’s profile through more radio play and more prominent display at retail locations. Al needed the company looking its best on paper because he was once again about to seek an investor: Jim had informed Al that he was ready to cash out.

Jim was looking at the business and it just didn’t look like fun. Gargantuan corporate power struggles, absentee overlords mandating minor internal procedures, the threat of Wild West shoot-’em-ups in the hallways—this was a long way from, gee whiz, the good old days of 1957 or even 1967. He could grow his hair long and wear wide lapels, but now people were smoking marijuana in the building, there was talk of cocaine. The conglomerate world was ever consolidating. Instead of big labels nipping at smaller ones, unrelated companies were gathered under big umbrellas. Wexler sold out to Warner Bros., but the following year Warner was bought by the Kinney Parking Company. Wasn’t Gulf & Western originally an auto parts manufacturer? The business was less and less about “record men,” people with ears who could pick or create hits. How long since Jim had been transformed like when he’d first heard Ray Charles? He looked admiringly at his sister’s exit. Riding out to his estate, Jim would pass near her apartment complex, and it must have given him pause. Having crossed into his early forties, he was newly aware of time ticking. He was hearing his exit cue.

The company was in a good place. Al had just broken the barrier with Sears. He was riding Shaft; his eyes were nationwide. He could put Isaac Hayes, Johnnie Taylor, the Staple Singers inside Camelot, Hastings, Peaches—the new world of record chains inside every mall being built coast to coast. Jim, however, was a fighter growing weary. His career in music was resembling his banking tenure. “I spent two years doing nothing but negotiating, back and forth from New York to California,” he says. “I hardly went to the studio. It drained me, mentally. I spent one whole summer in New York trying to get out of Gulf & Western and get the money to pay them off. We gave them a profit. Then we borrowed money from Deutsche Grammophon and the bank. The bank was paid back three million dollars in six months’ time, that’s how much money we made. Deutsche Grammophon, we had to pay them back plus about a million dollars profit. A lot of bad decisions were made. All the profits were going to other companies. And the company was being neglected because Bell and I were tending to these deals. I decided I wanted to get out once and for all. I wanted to go back to the studio and have some fun again. I told Bell, ‘I want to sell the company but I don’t want stock, I don’t want paper, I want cash.’”

“Jim said to me, ‘I want to get some money out of this operation,’” Al recalls. “So I had the responsibility, once again, of trying to sell the company.” He met with ready interest from RCA. “Elvis was alive at that time. I’m meeting with Rocco Laginestra, president of RCA Records. They offered us fifteen million dollars in RCA stock and I went back and told Jim about this great deal.” Al laughs as he remembers Jim’s response. “And Jim said, ‘Oh yeah?’ He said, ‘Man, I don’t want no more stock. I want cash money.’ I said, ‘But RCA is a blue-chip company.’ He says, ‘I don’t care who it is, Al. I don’t want anybody’s stock: I want cash money.’”

Generating an offer that would let Al buy out Jim with cash would take time and require assistance. There was really only one person Al could enlist to make that happen. So Al leaned on the lean-on man: Johnny Baylor. While traveling with Isaac Hayes, Baylor’s team had visited radio stations to take advantage of promotional opportunities. “They used to walk in the radio station, they’d lift the arm off that record while it’s playing, put theirs on,” says Randy Stewart, from Isaac’s entourage. “Wasn’t nobody going to argue with them.”

“We were on tour and Johnny Baylor had sent some of his guys out to pay some disc jockeys in Birmingham,” says Isaac’s drummer Willie Hall. “These guys were no fools. They stayed around in Birmingham the rest of that day to make sure that the jocks lived up to their agreement. These disc jockeys man, some of them were dogs, money-hungry clowns. They were gangsters themselves. But that was the order of the day then—disc jockeys getting their arms broken and their face beat in for taking payola and not playing records.”

Al and Johnny struck a deal that, in short, had them both betting on the future: I’ll gladly pay you Tuesday for a hit record today. Al wanted a strong cash flow so he could command the best price for Jim’s buyout. To push the company’s earnings higher, “I went to my dear friend Johnny Baylor,” says Al, “and explained, ‘I need you to take your team and go out and promote the Stax product.’ I said, ‘I can’t pay you for that. But what I’ll do is, I’ll take on the distribution of your label, and the manufacturing part of it, and that gives you compensation.’” That is, Al explains, “I didn’t want to create any additional expense for the company while I’m out trying to sell it.” In return for Baylor doing this promotions work, and for fronting the pay and expenses to his team, Al would assume the costs of Baylor’s record label and would agree to pay him later if their work paid off. Al and Baylor shared an economic philosophy, even if their means were different. “Those guys were on top of taking Isaac Hayes’s product to another level,” Al says. “And their motivation was different. The others were salaried employees, but in this particular case, there was a lot of black pride involved in what we were doing.”

“Johnny Baylor’s perspective,” says Dino, “was to see an African-American—boom—out there in the front. He wanted Al Bell to really be out there. And he would do anything that he had to to see that Al Bell would be all right.”

There was a financial risk for Johnny—Al was not going to provide any immediate income. But money clung to Johnny. “The devil was with Johnny Baylor,” says Randy Stewart, “because he had money all kind of ways.” None of the ways were obvious, but the money was.

Johnny Baylor became the face of Stax Records in the field. He’d follow behind James Douglass and the other promo men who paid visits to stations, the good cops who greased the turntables with money. Baylor’s team, the bad cops, would hit a town and you could almost hear his crew’s boots in lockstep as they fanned out to radio, retail, and distribution centers. Johnny Baylor would take a hotel room, and everyone his team came in contact with was told to reach him there. In a day, they’d make their presence known—word about Johnny would spread quickly. Retailers moved Stax product to the front of the store, gave it a big display; jocks played the newest Stax releases, giving them an extra spin. When one of Baylor’s team showed up, he’d be greeted with nervous smiles: “Hey f-f-fellas, you’re in town?”

Now here’s the kicker: Baylor would keep the hotel room for several days, maybe a week. DJs and store managers would phone the Holiday Inn, ask for his room. “I’m sorry sir, he’s not answering.” Thinking he’s still in town, they’d keep on pushing the Stax product, figuring Baylor’s pushing the presets on his car radio, and he’s someone you want to keep finger-snapping happy. In fact, Baylor and the gang may have already moved on to the next town, taken another hotel room for a week, started intimidating another city’s DJs and distributors. The Stax product received the extra push until the desk clerk said he’s checked out. Baylor could keep a whole region on its toes, Stax product everywhere.

“Other companies who had already established themselves in the recording industry were doing the same thing—getting airplay by any means necessary,” says Dino. “The top artists were selling millions of records, and some of that stuff is oopy-doopy stuff. But American music comes from gospel music, R&B, and jazz, so we felt that we deserved to be heard. We would meet the music directors and take up a little bit of their time to explain about R&B music. It was the way that we approached people, let them know that the African-American music needed to be heard.”

“Dino was an ex-boxer and he promoted records,” says Seymour Rosenberg, the Stax attorney. “He would open a briefcase and inside it was mounted a revolver. He would say, ‘Boom!’ and close it back up and, miraculously, his records got played.”

In addition to promoting at radio and retail, Baylor’s team collected on delinquent accounts, especially independent distributors who never wanted to let go of a dollar. “You gotta pay up,” says Dino. “Boom. There’s no getting around. A lot of distributors were holding back on the pay. And, well, we wanted to make sure that they paid now. There was some run-ins from time to time, and we got challenged a lot, so we had to really push our way through to those companies.”

“They kept Stax floating,” says Randy Stewart. “They were going to bring some money back. If you owe somebody and you’re not paying, there’s another way of getting it.” Randy declined to give details, only to imply that fists and guns had a way of making distributors locate money they’d been unable to find earlier in the conversation.

As Baylor settled into his work in the field, he suggested Al bring in another industry veteran, Hymie Weiss, whose experience and analytical eye would help them increase the sales numbers. “Hymie Weiss was a gentleman, a friend like no other,” says Al. “He’d had hits in the 1950s with Arthur Prysock. Hymie would fly from New York, stay at the Holiday Inn Central, run the sales department, and then fly back on the weekend.”

“I was the payola king of New York,” Weiss later bragged. “Payola was the greatest thing in the world. You didn’t have to go out to dinner with someone and kiss their ass. Just pay them, here’s the money, play the record, fuck you.” One of his Stax associates remembered Weiss as the guy who could buy a million records for a million bucks. The distribution of them might not have been clean, the sales may not all be accounted for, but the money spent, the generator whirred, and the cash register went ka-ching. Jim wanted out, but to get top dollar he’d wait for Al to make sure the company was moving lots of product, generating lots of income, attracting top dollar.

![]()

The success of the Shaft soundtrack would not seem to be a source of complaint. Yet Baylor quickly noticed a funny thing happening in distribution: Sometimes stores returned more copies than they’d ordered. He brought the news to Al. An ironic by-product to success: “We were growing so large, until it allowed for people to commit white-collar crimes,” Al explains. “You don’t have that happening in small, nothing companies.”

Pirating. That’s different from bootlegging (bootlegs are unofficial recordings released through unofficial means), different from forgeries (attempts to copy album art and musical content). Pirating requires insiders to cheat, insiders at the label, at the pressing plant, or on a delivery truck—someone who could access or create great quantities of the genuine article. Industry-wide, pirating was estimated to account for 10 percent of product on the market—the equivalent of what is often a small company’s profit margin. “We estimate that some 800,000 pirated copies of Shaft found their way onto the market in the States,” Stax corporate management consultant Adam Oliphant told an industry publication. “That’s something like 40 per cent [of the product accounted for].” Oliphant explained the pirate’s methods: “There is the straight-forward theft of legitimate product. This can occur within a pressing plant, the press operative working on the principle of ‘one for the company, one for me’ and then getting the records out of the factory and onto the market with the collusion of a shipping clerk, a security guard and a trucker or, where independent pressing plants are employed, the management themselves may fiddle their clients by over-pressing. Once these records get into the shops they are virtually impossible to detect.”

Stax was ready to pay high dollars to solve this high-dollar problem, and their New York law office led them to Norman Jaspan & Associates, an investigative firm that also advised Ford Motors. Al liked keeping such company. Jaspan sent in undercover operatives, and Stax bought infrared detection for shipping supervision, marking their boxes so that their representatives in the field could carry a special device to authenticate their product. “On a weekly basis I would get the reports,” says Al, “not at the office but at home.” Jaspan beefed up the studio’s security, creating a guard station and adding a vault that required two keys.

In November 1971, while Shaft was massive, two Stax executives who’d been at the company barely two years were fired. Ewell Roussell, vice president of sales, and Herbert Kole, vice president of merchandising and marketing, were accused of piracy. Both had access to the master tapes and connections at the pressing plants for records and art, and Stax alleged that they’d manufactured illegal albums and sold them for profit—about $380,000 profit. They’d also forced a kickback from local and national photographers hired for album covers and promotional shots—another $26,000. “Jim and I decided not to prosecute them,” says Al. “‘Go your way, we don’t want to send you through these kind of problems. You got family, kids.’ We were supposed to turn them in to the bonding company, the bonding company would have given us our money back, and then the bonding company could have caused them to be prosecuted. We let them go, and several other people, at that point in time.” Stax settled with the insurance for a tenth of what they’d lost.

(For his part, Ewell Roussell claimed not only innocence but also vindication, saying, “I lost my sales position at Stax Records because of something somebody else did, completely without my knowledge. Stax, through Jim Stewart, acknowledged by letter to me that pressure from its fidelity bond company caused my release and not any implication of me by the investigations. I still have that letter. The newspaper quotes have said that I received money from alleged kickbacks. I did not receive one cent and did not know of any such scheme until after my release. The bond company settled its claim with Herbert Kolesky [Kole], who had been my superior at Stax. They never even approached me about any claim because it was clear to them that they had no claim against me.”)

“Al was too compassionate,” says his assistant Earlie Biles. “A lot of people he brought in took advantage of him and the situation, because we grew so fast. He was bringing people in who had expertise in certain areas, but these people brought their own people in, their own ideas. We didn’t have policies and procedures in place, so they would all run to Al Bell for whatever they wanted. When they couldn’t get through me to see him, they would wait in the parking lot. They missed him there, they’d go to his house.” Earlie and her husband, living next to Al’s house, chased down the people who tried to get to Al by throwing pebbles at his window during the night. “The chain of command was broken.”

One casualty of that broken chain was Don Davis. In the various shufflings, he bounced from head of A&R back to staff producer and, despite all the Johnnie Taylor hits, wound up out the door. “Don came in my office a few months after he’d hired me,” says Tim Whitsett, “and said, ‘I’ve just been canned and I’m on my way back to Detroit.’”

To the consumer—to anyone on the outside—Stax appeared to be thriving. Despite Booker T. Jones and Steve Cropper having left the Stax payroll, the MG’s were still recording together, and their single “Melting Pot,” in early 1971, from the album of the same name, had fared well on both the R&B and the pop charts. However, the tensions between the group and the Stax staff were so high that the band recorded in New York, far from their McLemore home. A new direction, “Melting Pot” is more jazz-influenced than the band’s prior work, looser within its defined structure, a greater sense of impromptu jamming. (It remains a favorite for contemporary samplers.) This single and album would prove to be their last work on Stax—Duck and Al Jackson would release an album and single in late 1973 as the MG’s, with no mention of Booker T., and without much success.

But Stax’s original star was back on top: Rufus Thomas was enjoying hit after hit. In a slump since the mid-1960s, he’d teamed with newcomer Tom Nixon, a Detroit producer, and things clicked. “The Funky Chicken” went top ten in 1970, “(Do the) Push and Pull (Part 1)” went to number-one R&B and number-twenty-five pop, and “The Breakdown,” released in July of 1971, was on its way to top-forty pop and number two on the R&B charts, with “Do the Funky Penguin” to chart before the year was out.

Stax continued to aggressively license material from outside sources. Jean Knight’s hit “Mr. Big Stuff” had taken off in the middle of 1971. The song had come to the attention of Tim Whitsett when it arrived on a four-song tape from Malaco Studios in Jackson, Mississippi; they wanted Stax to license it and get it to the masses. Don Davis had rejected all the songs, but Tim thought three of them were really strong. After Stax declined their songs, the tiny struggling Malaco label released one itself. “Groove Me” hit the top of the soul charts and top-ten pop. With Davis gone, Whitsett had Stax reconsider the others. “We were being blessed and fortunate,” says Al Bell. “I’m sitting in my office one day on Avalon, right across from Jim, and I’m hearing this bass slam through a wall. I said, ‘Jesus Christ what a bass line. Poignant, poignant.” He went to Jim’s office, found out it was the relatively unknown Jean Knight doing a song called “Mr. Big Stuff.” “I said, ‘Man, we got to go to the street with this as fast as we possibly can.’” It went to number-one R&B and number-two pop. “It was,” Al says, “like manna from heaven.”

The Dramatics also hit big. They’d come to Stax through Don Davis in 1968, but departed after having no significant success. In 1971, they were re-signed on the strength of “Whatcha See Is Whatcha Get,” made with Davis in Detroit. Stax leapt on the song, taking it to the top ten in both pop and R&B, and earning a gold record for a million sales before the year was out. Albert King was also on the make, with “Everybody Wants to Go to Heaven” from his Lovejoy album, a career highlight produced by onetime Mar-Key Don Nix. The Emotions, the gospel band brought from Chicago and given the pop patina, charted with “Show Me Now.”

The Rance Allen Group was a gospel outfit that did not want to cross over, and Stax liked them so much, they created a new imprint, the Gospel Truth, just so they could sign them. “We tried to go to Motown, but Motown didn’t do gospel at all,” recalls Rance Allen. “The next step was Stax Records, and they didn’t do gospel either. But Jim Stewart and Al Bell liked what they heard, and so they called my manager to tell him they were interested.” No folly, Gospel Truth released three albums in 1971, and many more over the coming years.

Al Bell had taken over production of the Staple Singers from Steve Cropper well before Cropper’s departure. He’d produced a couple records and enjoyed some success—“Heavy Makes You Happy (Sha-Na-Boom Boom)” from The Staple Swingers had gone top-forty pop and top-ten R&B—but for his third album with them, Al took the family to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Muscle Shoals had become a notable recording center in 1961 when Rick Hall produced Arthur Alexander, whose songs were then cut by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones; Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” was recorded in Muscle Shoals, Wilson Pickett found more success there after leaving Stax, and the studios had developed top-notch house bands (on the Stax model). While preparing for the soul explosion, Stax developed a satellite relationship with the Muscle Shoals studios. By taking the Staples there, Al would be far from the office and not constantly distracted by phone calls. Plus, he says, producing at Stax was intimidating. “I don’t know flat from sharp,” he says. “I’m the other stuff.” To the staff, he was the marketing guy, and he felt his lack of musical knowledge would lower their opinion of him; outside Stax, he could be just another client. Just another hit-making, star-making client. With the Staples in Muscle Shoals, he cut “Respect Yourself” and “I’ll Take You There.” To ensure he’d get the best efforts from the musicians, he made the unusual arrangement of paying them a royalty on sales.

1973, backstage at the Mid-South Coliseum. L–R: Eddie Floyd, Rance Allen, Johnnie Taylor, Rufus Thomas. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

“Respect Yourself” grew from a conversation between songwriter Mack Rice, who’d written Wilson Pickett’s hit “Mustang Sally,” and Luther Ingram, Johnny Baylor’s artist. “When the administration moved out of the McLemore offices, they let everyone who was staying [the creative team] pick their offices,” says Rice. “I picked Jim Stewart’s office, man. It was plush, with long couches and zebra all over the floor. I felt like I was somebody then. So one day Luther Ingram and I was up there talking. One of us said, ‘A guy got to respect himself out here to get anyplace.’ It hit us the same time—that’s a good title, ‘Respect Yourself.’ Luther went downstairs to see Isaac about something. I’m messing with my guitar and Luther—what are they doing so long? I started writing. It was like God just give me the words. About thirty minutes, I had the whole song wrote and Luther never came back.

“The next day I turned in the song to the publishing department, told the girl down there, ‘When you see Luther, tell him to sign this contract.’ Luther told her, ‘I ain’t did no song with Mack Rice.’ She said, ‘I had to almost beg him to sign it.’ The song starts climbing the charts, Luther came to me and said, ‘Hey, man, didn’t I write some of that?’ I said, ‘No sir. I’m giving you ten percent of the song, though, ’cause one of us come up with the title.’”

The song jibed perfectly with the Staple Singers. “Pops would tell the songwriters,” says Mavis about her father, “‘If you want to write for the Staples, read the headlines—we want to sing about what’s happening in the world today.’ So Mack said, ‘Pops, I got one for you.’ Pops heard it, said, ‘Shoot, man, we could put that down.’” And they sure did.

Al, who’d been more occupied with business than songwriting, wrote “I’ll Take You There.” “My fourth oldest brother was murdered in North Little Rock, just as I was getting ready to go in the studio with the Staple Singers,” he told a reporter. “I had nothing but deaths among my brothers. Paul, the one after me, was shot down and killed in Memphis. My youngest brother, Darnell, was murdered in North Little Rock. I couldn’t come to grips with death.” After leaving the Arkansas graveyard, his family broke bread at his parents’ house. But Al got up and went outside, found himself pacing uncontrollably, the song welling up inside him, the sun heating him in his jacket as he walked. “My father had the relic of an old school bus under two oak trees,” says Al. “He used that bus to haul cotton pickers, and it was a reminder to him how he moved from an eighth-grade education to being one of the leading landscaping contractors in Arkansas. I sat on the hood of that school bus and tried to deal with all the emotions I was feeling. All of a sudden—I cannot sing, I cannot dance, I cannot carry a tune in a vacuum-packed can—but I can feel and I can hear. Then I started singing the lyrics:

Ain’t nobody worried

Ain’t nobody crying

And ain’t no smiling faces

Lying to the races.

I’ll take you there.

It wouldn’t leave, it stayed there. I kept trying to write other verses, but I couldn’t. Nothing worked. There was nothing left to say.”

Al took that verse to Muscle Shoals, where Mavis ad-libbed with the group as they jammed on a riff. Muscle Shoals guitarist Jimmy Johnson had just returned from Jamaica and had a single of the reggae instrumental “The Liquidator” by the Harry J All Stars; bassist David Hood and drummer Roger Hawkins had recently completed a tour with the British rock band Traffic and had been listening to Bob Marley. Funky rhythms were in the air, and the band locked into a groove that sent Mavis improvising a call-and-response with the instruments. “Respect Yourself,” released in latter 1971, went to number-two R&B and number-twelve pop, and “I’ll Take You There,” which wasn’t released until the spring of 1972, went to number one on both charts. Baylor’s troops on the street—promoting, enforcing, collecting—had no shortage of strong material to work with.

![]()

And then there was Isaac Hayes’s Black Moses album, his second double album of the year, released while “Theme from Shaft” was still number one in the nation. The rare artist can churn out copious work at a rapid rate and maintain a high level of innovation. But Isaac Hayes was putting out music faster than the Beatles in their prime. Black Moses is not a bad record, but it doesn’t move Hayes’s career forward, and with the glut of his material in the marketplace, this album came off as stale.

The name “Black Moses” had first come from Dino Woodard. “Isaac was a great leader,” he says, “And one time at the Apollo Theater their MC was late, and I introduced him as Black Moses. The audience was just overwhelmed.”

Isaac initially found the name sacrilegious, but a Jet writer picked up on it, as did other MCs in their introductions. Stax capitalized on a growing trend. Larry Shaw, Stax’s advertising and packaging chief (whose Stax work had already won several national awards), didn’t like the record at all, and told writer Rob Bowman, “The music in there was of such poor quality, we had to sell the box it came in. We put an inordinate amount of money into that album jacket. It was to capture fully all the things about him that were not in the record. The record was the box.” Shaw created a gatefold that unfurled in four directions, shaping into a cross four feet tall and three feet wide, with Isaac in an Egyptian-looking tunic, his arms outstretched, an all-enfolding embrace of his tribe.

Concurrent with the album’s release was an antipiracy publicity storm. Having lost much profit to pirates with Shaft, Stax made its stance known through press releases, press conferences in New York, and filmed announcements for television. The label would be “utilizing ex-FBI operatives . . . [They] will institute close surveillance tactics at the fabricating plants, pressing operations, and known bootlegging operations throughout the U.S. FBI methods will be utilized in detecting and apprehending pirates.”

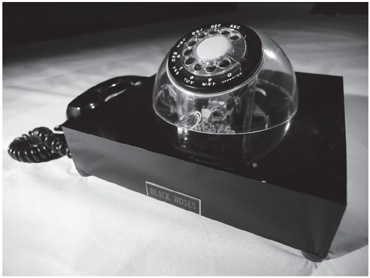

Expecting big sales for Black Moses, Stax spared no expense. To its most influential people—DJs, radio station directors, owners of the largest distributors—Stax sent a space-age telephone, equal parts James Bond sleek and Daddy Mack pimpin’: The size of a small tabletop, the device featured a clear plastic dome through which the phone’s electronics were visible; the rotary-dial face protruded like a breast offering itself. The handset extended from the left side of the fine wood-grain box. It was sure to win favors, and likely helped important Stax supporters impress their dates.

Stax’s excesses were growing. Another promotional phone came in a wood-and-leather case; lift the lid to reveal the phone ringing within. Elegant, futuristic. Stax gave away beautiful Bulova watches; a crystal desk set that evoked a lofty religious ceremony but was actually a sword-and-stone letter opener; a fine leather shoulder satchel embossed with the finger-snapping logo; a silver tea set. In addition, Shaw designed no end of everyday giveaways: a package of playing cards, two decks side by side, one with the Stax logo on the back, the other with the Volt logo. Both also promote the Hip and Enterprise subsidiary labels (Hip was oriented toward white pop, and Enterprise was home to Isaac Hayes); the cards bear the motto: THE SOUND CENTER OF THE SOULAR SYSTEM MEMPHIS TN. There were Stax oven mitts, keychains, refrigerator magnets, and posters of all kinds.

Promotional telephone for the Isaac Hayes album Black Moses. (Photograph by David Leonard)

Black Moses spent nearly two months at the top of the R&B album charts. Hayes’s edited version of “Never Can Say Goodbye” reached number twenty-two on the pop charts, and the top five on the R&B. At the start of 1972, he was nominated for seven Grammy Awards and numerous other accolades. He seemed invincible, and it was a perfect time to negotiate a new contract. For several years there’d been talk about giving Isaac equity in the company, and while Al couldn’t promise that at a time when he was trying to find a new partner, Al knew he’d never have a partner if Isaac got away. If this new contract were clothing, it would have fit only Isaac. Among numerous lavish perks, his new deal included a $26,000 gold-plated Cadillac, a leased house in a canyon near Hollywood, a very sweet royalty deal, and annual salaries totaling $55,000 for the administering of his publishing company and for himself as a producer—despite his production work having fallen off dramatically since he’d become an artist. Other than Billy Eckstine, Isaac had mostly just finished prior commitments with David Porter. Such outlandish payments were the price of keeping the Isaac Hayes generator humming.

Much like Hayes’s contracts and his album, Stax had become outsize. The company’s early-1970s phone directory had an intimidating two hundred names, many with multiple extensions. In the new Stax Organization, employees wandered the halls not knowing each other’s names, even what their jobs were. Since the chain of operations had been initially revised in March 1970 by Jim Stewart, it had changed time and again. Problems were solved by hiring—a fixer, a specialist, a new department. “How are you gonna put a song on the turntable and statistically analyze it?” Deanie Parker asks of the department of statistical analysis. “It was getting crazy, just crazy.” The magic wand is waved. A new department is created. Middle-class wage is granted. Plus five. The tally of Al’s upwardly mobile employees rises.

“There was a lot of head games going on, political games as the company got bigger,” says Jim, who was working on his exit. “I didn’t like that, but there was no way I could stop it. You got a hundred and fifty, two hundred people, it’s not like it’s six people you can talk to every day. We were getting too big, the overhead was getting out of hand. At some point I felt that it was growing into a monster that could devour itself.”