Union Planters National Bank was not in the music business, but it had become one of Stax’s closest associates. “We had a great relationship with Union Planters,” says Al Bell. “Matter of fact, we would keep a million dollars on deposit in a checking account just to provide additional funds for the bank instead of putting it in a certificate of deposit. It was that kind of working relationship.”

The cash on hand must have been very helpful, assuming that the bank noticed. But they were a disorganized, improperly administrated institution. “Union Planters got very, very sloppy in its lending controls at the high, wide, and handsome age of the early seventies,” says Wynn Smith, an attorney retained by the bank. Their problems extended from several areas, all of which might have been prevented by better oversight within the bank. In 1971, the bank expanded heavily into real estate loans, though it did little preparation or research, nor did it monitor how its new clients actually disbursed its funds. Further, says attorney Smith, “Union Planters had a project in the early seventies called ‘Your Signature Is Your Collateral,’ and they started going crazy making installment loans on automobiles. It was so easy to get a loan that people were coming from all over the country to buy very expensive Cadillacs, and then taking off with the Cadillacs and not paying the installment loans.”

The inherent problems in the new ventures came to light when, in late 1973, interest rates began to rise nationally. At the same time, inflation was rising and so was unemployment, creating an economic recession that plagued the country until well into 1975. According to The Turnaround, a book written about the Union Planters fiasco (and its redemption), “The liability ledger of the bank was organized in such a manner that it was impossible to determine whether one loan was related to another. No employee of Union Planters knew what the bank’s total exposure was.” This description, the bank would soon find out, could also apply to Stax—not just regarding loans, but all bookkeeping.

The bank’s situation got so far out of control that federal authorities took notice. UP’s earnings dropped by half in the first nine months of 1973, with losses in the third quarter exceeding half a million dollars. By the end of 1973, UP’s investment division was under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The threatening sound of sabers rattling in Washington was more compelling than Stax’s nearby funk, and the bank focused on making a plan to save itself. Despite the frequent payoffs, Stax still owed UP close to $10 million, including an overdraft of nearly $1.7 million. Union Planters needed new collateral.

The record company was deep in hock, joined recently by the publishing company. There was no mistaking that the debts were high. But Stax’s outlook was promising. The European distribution deal would soon be up for renewal, and Stax intended to hike its license fee. Isaac’s Two Tough Guys soundtrack was imminent, sure to be a smash like all his albums were, maybe even bigger than Shaft, since he also starred in this movie. On its heels would be Isaac’s soundtrack to the blaxploitation film Truck Turner. In the past five years, Isaac had released five albums that each did more than $2 million worth of business. The patterns indicated another welcome influx of money.

Jim contemplated the company’s position from his fifty-six acres. It was very quiet there. He’d come from the country, and the dense trees on his estate reminded him of his childhood in Middleton. But the house did not. He could have fit perhaps every house from his hometown into the vast complex that was now the Stewart home. The old Capitol Theater would fit inside, and all the McLemore block he’d worked so hard to purchase. Jim, his wife, their three kids—it was like their own private country club. And it was quiet.

Jim would turn forty-three in a few months. He’d been mostly away from Stax the past year and a quarter. The pressures had greatly diminished, the constant thrumming of the business in his ears and eyes and brain had finally quelled. He’d missed much of his children’s childhoods, and soon they’d be off on their own. This opulently feathered nest he’d finally built was soon to be empty. And quiet.

Music had made him independently wealthy. He’d collected, finally, on the years of long hours and hard work. He’d enriched Atlantic, he’d enriched Gulf & Western and Deutsche Grammophon. He’d stayed three more years after his sister left, and the company had mushroomed in size and success. His break with Stax came when they were thriving, and it made both them and him wealthy. Al wanted total control of the total record company, and he’d gotten it, and he’d received a swollen bank account courtesy of Columbia Records, who’d also swelled Jim’s account. Whatever shape the company was now in, Jim was not responsible for it. He did not need to help.

Since retiring, when not in Florida, Jim mostly spent his days at home. He didn’t use the tennis court much. The big pool’s high diving board rarely rattled. Jim didn’t often swim in any of the four pools. It was nice when the kids did, but even that was infrequent. He’d thrown big parties at the house, but that period had passed; big parties never really excited him. Living the dream was different from yearning for it. He could look at his many amenities on his many acres and say he had it all. Or he could consider how little these amenities meant to him and, soaking in everything around him, he could say he’d lost it all. Where was the challenge? Where was the grit that made the pearl?

Jim spent his money and time, both too plentiful, on jigsaw puzzles. Since leaving Stax, he was often at the family’s expansive dining room table, alone. He’d open a thousand-piece jigsaw-puzzle box, turn the pieces faceup, separate the border pieces. Step by step, he’d assemble an image—a landscape, perhaps, pastoral and distant that he’d never visit. Completing it, he’d throw the pieces back into the box and open a new one. He was a builder, a producer, and what the hell was he supposed to produce by himself as he sat in the quiet and looked at the long, hushed second half of his life? Forty-three wasn’t old. He had energy, he had ideas, vitality. And money.

In February 1974, unable to let go of the one great change he’d wrought upon the city and world, Jim pledged more than everything he had to the bank. He gave Union Planters a personal guaranty against the company’s loans, putting up all he held, including the millions he’d recently collected, and all he was to receive. That is, if ever there were a problem, the bank would know that Jim’s personal wealth was available to make up any financial insufficiency. (Though it’s odd that the payments to cover the faltering company would come from the faltering company, Jim already held substantial assets. If Stax paid him no more money, he’d still be wealthy.) Jim was a family man, and one of his children was Stax. And even the child who grows up to spurn you, the baby you shaped and raised who morphs into something you don’t like—you are forever attached. If that child needs you, you give your all for that child.

“I reacted with my heart instead of my head,” he told writer Rob Bowman. “It was an emotional [decision], not a prudent, sensible one.” After making the pledge, Jim promptly put nearly half a million dollars of his personal money into the company to help cover the operating costs. He was affirming his belief in the company’s mission: with his heart, his soul, his wallet, and his children’s future.

It was an epic move. Jim was a quiet man, conservative, and yet he’d been the one to alter the course of history, to create in a racist and stratified society a space both inclusive and collaborative. Like Superman, Jim turned society’s tracks. A white country music fiddle player making his name in African-American soul music? If he’d asked anyone, they’d have said it was a stupid idea, it can’t be done. If he’d reacted with his head, he’d have backed away. Stax grew despite logic and circumstances. Stax was not a “prudent, sensible” decision.

He placed all his chips on a single bet. He held nothing behind, no fail-safe, no extra feathers, no spare million bucks. Jim could help, and he did.

The following month, March, Stax took another sucker punch from Columbia. Due to the high number of records that Stax had delivered to Columbia, and with no discernable market need for more product, Columbia announced it would begin withholding 40 percent of what it owed Stax to help cover the costs of returned product. Returns? The howl in Memphis could be heard in New York: Get the records to market! There won’t be returns, and there will be more money for everybody, if you’ll just do the one thing you are supposed to be good at: Get—the—product—on—the—shelves.

Though their relationship was really about one thing—distribution—Stax and Columbia could never get on the same page. “From the beginning of the argument over who would control the branch distributors, record sales started dropping.” Jim says. They couldn’t agree on the basics of getting records to stores. “So many hours and days were spent trying to straighten these matters out, trying to get the philosophy and the people working together in concert.” Jim sighs. “It could never be accomplished. When the principals are involved in something extraneous of producing and marketing and promoting and selling records, which is your business, the inevitable occurs. Records sales start dropping. I’m not talking about a month or two months. This became continuous and it got worse and worse and a dichotomy was struck between the personalities involved—between our people and CBS’s people. The problems became monumental—and then the financial problems resulted from that.”

The tough times were becoming increasingly evident to Stax’s staff. Polydor did not renew its European distribution, and though new deals were made, they were smaller. “There were some speeches that Al gave that were designed to keep the situation together,” says Deanie Parker. “None of us was oblivious to what was happening with CBS, and we knew Union Planters was beginning to stink. We could feel it. Several of us had a travel card—could go to an airport and charge a ticket to anywhere we wanted to go. When we got a memo saying to discontinue using them, you knew.”

In a late 1973 speech, Al was already acknowledging the company’s problems, but attributing their causes to outside sources: “The energy crisis is severely affecting industries which depend upon petroleum and its by-products for its operation . . . Unless the Stax Family can pull together to achieve these [cost-saving] objectives, management will be forced to consider extreme measures, resulting in employee layoffs, possible reductions in salaries, or both . . . Although on occasions in the past the company has given Christmas bonuses during the holiday season, we are unable to do so this year . . .”

The energy crisis was raging, and while the resulting higher costs contributed to the problem, including a hike in prices of the raw materials from which records are made, not to mention the cost of shipping them, the Stax crisis also involved a different kind of energy. Al’s speech was thirty-one pages long, and it ground over corporate structure and attitude. “Our people didn’t have the background or experience in training and management and departmentalization,” says Deanie, “but there were some on the staff who’d have held up their copy of that speech and exclaimed, ‘Ah, yes! This will solve the problem!’” Deanie shakes her head. “Those speeches went on and on and on. It was like a vexation of the spirit.”

The cash flow that Stax had so enjoyed began to evaporate while expenses rose. “It just grew too fast,” says Earlie Biles, “and we didn’t have enough sales to support all the people. We were hiring executives right and left, attorneys, CPAs, marketing and advertising execs.” The company’s annual payroll rose from $900,000 at the end of 1972 to over $1.4 million in mid-1973.

Stax never stopped producing good music; the releases just became harder for buyers to find. Disco was taking dance music in a new direction, further from the church influence. But Stax’s soul music still found an audience. The Staple Singers continued to work with Al Bell, having a solid hit at the start of 1974 with “Touch a Hand, Make a Friend,” top-five R&B and nearly top-twenty pop; not as gritty as their previous hits, nor as their next one, “City in the Sky,” which went to number-four R&B. They would have four more releases on Stax, staying on the company roster to the end. The Dramatics hit the soul charts, as did William Bell, Eddie Floyd, Veda Brown, the Emotions, and Inez Foxx. Albert King’s “Crosscut Saw,” a staple of blues bands worldwide, has enjoyed a long life since its October 1974 release. Johnnie Taylor hit number thirteen and broke the Hot 100 with “I’ve Been Born Again.” He almost broke the R&B top twenty that fall with “It’s September,” and he became Stax’s last charting artist with “Try Me Tonight.” His final single, “Keep on Loving Me” could have been a pop hit, but it got no real distribution.

The Bar-Kays continued to evolve and grow. Though heavily influenced by Isaac, while he went deeper into the lava lamp, the Bar-Kays moved toward the strobe light. They reworked classic soul sounds with “You’re Still My Brother,” a tune rife with social message. “It Ain’t Easy” is as spare as “Brother” is full, a vocal atop a keyboard riff, and sometimes little more than hand clapping. “Coldblooded,” largely instrumental, sounds like they’re fishing for a movie soundtrack. The appropriately titled “Holy Ghost” was their last release on Stax and Stax’s very last single (November 1975, though it may not have actually reached stores). It’s a bridge to the future, proof positive that despite all the business distractions in which the office was mired, good music was still being made.

Quality, however, was giving way to quantity. Between the start of 1973 and the end of 1974’s first quarter, Stax placed nine singles in the R&B top ten, and one in the pop top ten. The label released, however, seventy-four singles. The output was multiplying the expenses, and the hits were diminishing. “We had less than a hundred, and all of a sudden we had two hundred on the payroll,” says Jim, who was not the kind of boss to return and fire whole departments, even though his wealth was at stake. “Apartments in New York, houses in LA, a quarter-of-a-million-dollar Billy Eckstine contract. Bell needed that conservative bastard saying, ‘You can’t do these ridiculous deals.’ It’s high rolling.” Jim also believes the music suffered, refusing to blame the lack of sales on Columbia. “We had seventeen promotion men ourselves. We’d been promoting records before and selling them, so why couldn’t these same seventeen men go out and make hit records? Simply because we didn’t have hit records.” Being under federal scrutiny—for taxes, for payola—didn’t help either.

Columbia’s lack of distribution was not, however, a figment of Stax’s imagination. Stax’s distributor in Memphis, Hot Line Records, was unable to get Stax product “almost from the day the Columbia deal began,” remembers one prominent employee. “We couldn’t buy the records to distribute them. It was clear Columbia was trying to put Stax out of business.”

“You’d hear the horror stories from the promotions guys about the inability to get Stax product into the marketplace,” says Deanie, “and we’d see our records sliding from the charts.” Stax addressed the problem by expanding its promotion team, ramping up for a batch of albums geared toward the white market. Joe Mulherin, the trumpet-playing publicist, was on the road with Larry Raspberry and the Highsteppers, a white rock and roll group signed to Enterprise. They had a raucous, traveling-minstrel vibe (à la Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen) that included Don Nix (who was also coheadlining the tour), British blues sensation John Mayall, vocalist Claudia Lennear (who’d performed with the Rolling Stones), and drummer Tarp Tarrant (from Jerry Lee Lewis’s band, then a free man between felonies). The band had played both American Bandstand and Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert. They were subjects of a forthcoming documentary, Jive Assp. Many of their shows were sold-out and simulcast on radio. Larry Raspberry and the Highsteppers were hot. But touring the West Coast in the spring of 1974, they couldn’t find their record in stores. “Fans were complaining they couldn’t get the recently released Highstepping and Fancy Dancing,” says Mulherin. “Members of the band canvassed record stores and couldn’t find a single copy. People loved that band but couldn’t turn their friends on to the album. The shipping had simply stopped.” The band did not take the matter lying down. “Our manager addressed this with the Columbia people and was told he was full of shit.” Columbia was so powerful that empirical facts could be dismissed.

As the distribution giant unilaterally revamped the deal, Johnny Baylor stepped from his own morass to help. If Columbia’s Jim Tyrell was in charge of getting records into the stores—as he indeed was—then surely he’d recognize a demand from Johnny Baylor that Mr. Tyrell do his job. “We had become very close to Al,” says Dino. “Johnny was angry that CBS Records was ripping Stax off. They wasn’t putting the records out properly. I really felt that they wanted to kill Stax Records, because of the challenge to them. I thought that CBS just did the thing on them.”

So Johnny had a brief, charged conversation with Mr. Tyrell. “Johnny Baylor made a threat to Jim Tyrrell,” says Logan Westbrooks. “‘Follow Al’s dictates or else.’ And Jim Tyrrell was not intimidated. He came from the streets. He stared it right in the face. So that was the beginning of that little dispute.”

That little dispute quickly attained great size. In April, while Stax was down, Columbia hit ’em again: In light of this backlog of stock that Stax refused to acknowledge, Columbia was going to keep the $1.3 million it owed Stax. Stax’s quarterly payroll in March 1974 was $567,000—well over $2 million per year. Al attacked the problem. He hired his brother Paul away from General Electric (where he was a vice president) to head a new department of new hires at Stax, Retail Relations. “My brother staffed up a division doing nothing but calling retailers so we were able to document for CBS, ‘This store number, this person, this is the product they ordered, you didn’t ship it.’”

Al assigned Stax’s comptroller, Ed Pollack, to sort out the delayed payments with Columbia, and though he made many trips to New York City, he was unable to loosen any cash flow. That same month, behind the scenes in the IRS’s Stax investigation, chief bean counter Pollack was given immunity from prosecution, promptly revealing names of disc jockeys and amounts of cash paid. The IRS contacted them all; one admitted that Stax paid his son’s college tuition. At the same time, Washington Post columnist Jack Anderson was reviving his recording-industry investigations, revealing misdeeds. An ill wind was whipping up to a gale.

During the storm ahead, Stax discovered among subpoenaed Columbia papers a document entitled, “A Study of the Soul Music Environment Prepared for Columbia Records Group.” The thirty-page industry assessment, commonly known as the Harvard Report, had been submitted on May 11, 1972, prior to the Stax deal, by Harvard Business School master’s degree candidates at the instigation of a Columbia Records executive (and Harvard alumnus). There has been much speculation about Columbia’s actual intent with Stax, with some Stax officials citing the report as proof that Columbia was trying to cripple and then overtake Stax. The report, however, does not support the notion of Columbia buying or taking over a soul music label. It encourages Columbia to add soul music to its offerings, recommending the establishment of a black music division, staffing it with black personnel, and also suggesting Columbia make better black music than it had been making (a business school perspective on art). It suggests great profits can be made, but it warns Columbia against purchasing or taking over, by name, Stax, Motown, or Atlantic. Clive Davis claims never to have read it, and his dealings with Stax support that, as he ignored the various recommendations as much as followed them. Some parties wanted to make the report into the smoking gun that confirmed Columbia’s malicious intentions, but the report’s influence seems not as great as the conspiracy theories surrounding it.

There were other dictates that Columbia did follow. “The corporate philosophy of capitalism is, ‘If there’s a share of the market that you want, either you buy it, steal it, or destroy it,’” says Al with the knowledge of hindsight. “That’s the American way. I was talking to Kemmons Wilson [founder of Holiday Inn] and he explained how they took over rug companies to put rugs in all the Holiday Inns. The big fish eats the little fish.” The expansion deal that Al thought he was getting into was becoming a suffocation experience; Stax’s product was not getting into stores, and money was not flowing in. This was a threat not only to Stax as a corporation, but also to its artists and employees. Isaac’s massive payroll, for example, relied on timely payments from Stax.

CBS, to this day, denies any bad intent. “It was never a conspiracy on the part of CBS Records to put Al Bell out of business,” says Columbia executive Logan Westbrooks. “CBS was in the business to sell records, to make money. And they did it very, very well. I sat in on every last one of the meetings, and I never got the impression that CBS wanted to bury Stax or take it over. If the retailers are calling for product, then with a very, very short turnaround, we can ship it in there and meet the need.” Westbrooks says there was no demand for Stax product.

One of the battles between Columbia and Stax had been a bidding war earlier that year for a hot new United Kingdom act. It wasn’t a black London soul singer preaching Black Power to an international audience, it was not a rock band carrying blues to a new crowd. Al’s desire to sell more units brought him to outbid CBS for the contract on a prepubescent white Scottish girl named Lena Zavaroni. She was ten years old, the youngest artist ever in the UK album chart’s top ten. She sang standards and classics, leaping from a TV talent show into adoring hearts. Her fans included Frank Sinatra and Lucille Ball. “Lena Zavaroni was very good,” says Stax publishing executive Tim Whitsett. “She sounded every bit as adult as Rosemary Clooney, and that’s the type of music she sang. We were getting away from our core.” Though Stax had never had a big hit on a white artist, Al wanted her album, Ma! He’s Making Eyes at Me, to spearhead his next Stax tidal wave into white America’s living rooms. Big money was paid for this coup. And they sold well over one hundred thousand copies, a quantity that once had been a hit at Stax. But in this case, they’d pressed and shipped more than six hundred thousand copies.

Through Zavaroni’s manager, Al licensed the soundtrack to a South African stage play. He expanded his foray into that distant market by sponsoring a weekly radio program there, an hour in which only Stax records were played. Al had the legal department establish copyright and imprint trademarks there and in numerous foreign markets. “I know they opened an office in Paris,” says Don Nix. “I went down there and I just said, ‘My God, I wonder how many copies of ‘Who’s Making Love to Your Old Lady’ did they have to sell to pay for this?’ It was waste, just rampant waste.” Tim Whitsett was equally disquieted about the home front: “It got bloated, especially in some of the projects we took on, some of the artists we tried to put out that just didn’t seem to fit, expansive ideas that seemed to stray, like movie production. Our eye was not on the ball anymore. We were looking up in the stands.”

Stax won the bidding war for Lena Zavaroni in 1974.

![]()

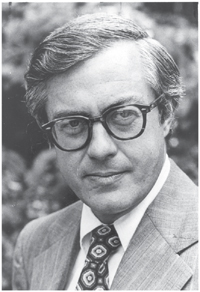

Inattentiveness to the bottom line seemed epidemic in Memphis. The situation at Union Planters got so bad that the president of both the bank and the bank’s holding corporation resigned. For its rescue, the bank hired a young man who had shot through the ranks of First National Bank of Atlanta by writing an organizational and marketing manual. Organization was exactly what Union Planters needed, and on May 13, 1974, William “Bill” Matthews was named president of the bank’s holding company—at forty-two, the youngest person to ever hold such a position in America. On his first day at work, he learned that the Securities and Exchange Commission was investigating the bank and threatening to sue them. He was also confronted by operational and organizational chaos; when scrutinizing the bank’s loan portfolio, he found it so badly managed that it actually cost the bank money to make the loans—the more money it loaned, the more it was losing. Stax was among its largest loan customers.

“The Comptroller of Currency and the bank examiners came in to close the bank,” recalls Al. “It was about to go under when they brought in William Matthews. I was called by some of the old officers to come meet this new person. We were high up in their building looking out at the Mississippi River and having this casual social conversation and all of a sudden this gentleman that was sitting over in the corner said, ‘Al?’ And I looked and said, ‘Yes?’ He said, ‘Al, I don’t want you to think that I’m a redneck from Georgia.’ They’d introduced me to him by name but I didn’t know who he was. So I said, ‘Well, I don’t and I won’t as long as you don’t think I’m a nigger from Arkansas.’ And that’s the way the relationship started between the chairman of the board of the holding company of the bank and myself. And our interaction from that day to the very last day was like unto that. I knew at that very moment that that was a one-on-one fight.”

William Matthews, chairman of the board, Union Planters National Bank. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections)

Matthews had his hands—and fists—full. He held the federal investigation at bay by conducting his own. In July, less than two months after coming on board, he discovered both a kickback scheme and a quarter-million-dollar embezzlement scheme involving loans to fictitious people. One of the participants in the latter was Joe Harwell, a bank employee for nearly fifteen years, and Stax’s loan officer.

In 1974, “Stax’s total indebtedness to Union Planters amounted to the principal sum of $10,493,220.06 plus interest,” trial documents reveal. Pursuing his loans’ security, Matthews found no collateral that justified so many dollars and he sent a team of auditors to Stax. “We tried to reconstruct the books,” he told a newspaper, “but they didn’t really have any books in the normal sense of the term. They appeared to be able to generate $13 to $14 million a year in revenues. The problem was expenses. It was hard to tell what was happening with the expenditures.”

On the one hand, Stax’s books were no different from any other record company’s—or, for that matter, any appliance manufacturer’s or any doctor’s office’s: All would have slush funds that would be hard for an outside accountant to decipher. Some larger, some smaller. Then again, there’s Baylor’s $2.7 million in nine months; the bank’s audit also discovered a $250,000-a-year apartment Stax was paying for in New York—occupied by Johnny Baylor. “Why,” Matthews asks, “was Stax paying this man all this money?”

![]()

By the summer of 1974, when President Nixon resigned, the music industry was a pop culture pariah. Payola scandals were wide open and CBS-TV broadcast a prime-time documentary, The Trouble with Rock, laden with implications of malfeasance throughout the music industry including at Columbia Records, the network’s own corporate relation. Stax’s relationship with Columbia had, by then, become outright adversarial. The lack of Stax records in stores seemed purposeful: Columbia could prevent sales by withholding shipments, send Stax to its knees, then cherry-pick the talent it wanted. “After Clive Davis left,” says Al, “there was really nobody for me to call, because the only person I knew inside of Columbia was Clive Davis.”

In July 1974, Stax bought its own pressing plant, a facility in nearby Arkansas. In addition to boosting its brick-and-mortar assets, owning the plant would, after the initial monetary outlay, reduce the cost of pressing, and allow the label to make profits pressing for others. The facility was a converted chicken coop, and its equipment was none too precise, with some records coming out a bit too wide to spin on a turntable.

Jim Stewart, motivated by many factors including the protection of his personal guaranty, stepped up to create additional revenue streams. After a two-year absence from the recording studio, he returned to sign and produce Shirley Brown. She’d been touring with Albert King, who brought her to the label’s attention. Her voice had an Aretha Franklin–like quality—she even cut Aretha’s standards “Rock Steady” and “Respect” at Stax—but Jim focused more on the intimacy she conveyed, the way she courted the listener’s ear. The song “Woman to Woman” had been floating around Stax, rejected by several female vocalists. It has a long spoken introduction—she finds another woman’s phone number in her man’s pocket, and calls to introduce herself and stake her claim. Shirley’s delivery is compelling, like it would be rude to ignore her. Jim proved that his antenna was still tuned, his production skills exquisite.

There was a sense of reunion to the session, with Al Jackson and Duck as the rhythm section (Al also coproduced), Marvell Thomas on piano, Bobby Manuel on guitar, and Isaac’s arranger Lester Snell on organ. The resulting song was too good, in fact, to waste on Columbia, who would only warehouse it. Stretching the legal limits of their contract, Stax created the Truth label, a subsidiary outside the Columbia agreement, and put to work its arterial relationships with the distribution outlets where the connections were still strong. Released in August, “Woman to Woman” went to number-one R&B in November and high up on the pop charts; before year’s end it became a gold record. “‘Woman to Woman,’ the last record I did, was, ironically enough, a million seller,” Jim says. He pauses, then adds, “Too little, too late.”

Stax had been missing payments—to vendors, to employees, to artists. Like weeds, the lawsuits quickly flourished. The initial grievance tore to the company’s soul. On September 10, 1974, Isaac Hayes sued Stax for $5.3 million in a federal civil suit. The company’s July 26 check for $270,000 had been returned for insufficient funds; Isaac’s tax payment to the government bounced with it. (He’d negotiated a $1.89 million contract for the period February 13, 1974, to January 20, 1977, payable in seven equal installments of $270,000; this was the second installment.) Like Stax, Isaac was finding himself in desperate straits. His lawsuit attacked with a vengeance, claiming Stax had cheated his royalty statement since 1968, that the label had not properly promoted his records, and that he’d been billed $100,000 for promotion in violation of his contract. Much of the suit’s language expressed dissatisfaction with and anger at Al Bell. Isaac said Al had promised him equity in the company, had declared a “feeling of brotherhood” for Isaac, had told him in 1968, “We are going to be together and share all benefits all down the line.” Isaac asked that his relationship with Stax be terminated and he be allowed to negotiate a new contract with ABC Records, the proceeds of which could help satisfy his personal debt to Union Planters National Bank. “Isaac didn’t do anything more than the average artist does when he reaches a certain level,” says Deanie, “and that is to become a little bit more difficult to work with.” The suit was settled a week later, out of court, with a promise for an undisclosed sum and the return to him of all his masters and copyrights, and the release from his contract. Al Bell’s organization had been built on Isaac Hayes’s back. On what now would it stand?

At that same time, to avoid another court debacle, the master tapes belonging to Richard Pryor were returned, and his contract terminated; he’d sold well, but the income he generated was absorbed before Stax could pay him royalties. Stax had made him a star but couldn’t keep him a star; he’d go to Warner Bros., where That Nigger’s Crazy would be re-released, to enjoy his days in the sun.

Before the month was out, a federal grand jury subpoenaed records of all Stax’s financial transactions from 1973. The investigation was part of Project Sound, the ongoing nationwide inquiry into recording-industry kickbacks. Documents covering the two prior years, and all testimony before the jury, were released on October 15 to the IRS “for the purpose,” stated US District Judge Robert M. McRae Jr., “of determining whether there are additional tax liabilities due.”

On October 9, 1974, in the wake of the success of “Woman to Woman,” Columbia sued Stax, accusing it of breaking its distribution agreement. Lawsuits being the day’s preferred mode of communication, Stax answered with one against Columbia, suing for $67 million, claiming that Columbia breached the distribution agreement to gain control of the company, citing the Sherman-Patton antitrust laws. Attorneys claimed that during the two-year relationship, Columbia had overordered Stax product, then left the records “unsold in the warehouse of CBS.” They stated that Columbia had withheld more than $2.32 million in sales proceeds due to Stax under the agreement and had “willfully, wantonly, and maliciously” attempted to force Stax out of business. Because of the withholding, Stax claimed, it was unable to meet its payroll, causing it to lose Isaac, among other damages.

“I had the international accounting firm of Price-Waterhouse come in and value our masters,” says Al. “They put it at sixty-seven million dollars. And we started out fighting with a major law firm—Heiskell, Donelson, Adams, Bearman, Williams & Kirsch—which became Senator Howard Baker’s firm. That was one of the most prestigious firms in this state and they wouldn’t have taken on an antitrust suit against CBS unless they believed in the validity of that suit.” The attorneys claimed Columbia “calculated to destroy Stax as a full service record company and to reduce it to a mere label or production company, completely under the domination and control” of Columbia.

Matthews, the bank chairman, recognized the potential of the antitrust suit, and he wanted to put his team of lawyers on it; helping Stax win it could help his bank. “He called me in,” says Al, “and said, ‘I want you to give this antitrust lawsuit over to the bank. We can win this, you can’t. We’ll give you two or three million dollars out of it.’ I wasn’t going to give him a sixty-seven-million-dollar lawsuit and he’ll give me two or three million dollars. If he’d said, We’ll split it down the middle, maybe I could have heard him.”

During the Stax troubles, Westbrooks remembers Columbia’s worry about its reputation in the African-American community. “CBS was concerned about their image on a national basis, especially with black radio stations and black disc jockeys,” he says. “Al Bell was a very, very popular figure in the national black community.” In fact, Columbia tried to bring Al under its umbrella, offering him a corporate vice president’s position overseeing its distribution network. But moving from Stax to Columbia would have, Al felt, been shirking his responsibility and moral obligations. “I said, ‘I can’t do that. You want me to be a Judas and sell out my people.’”

Al was called to a meeting by Arthur Taylor, the young, starched, and suave president of CBS, Inc., not just the record division, but the man to whom all the media heads—records, television, radio, the whole empire—answered. “I went up to the thirty-something floor in the New York CBS office to see Mr. Arthur Taylor,” Al says. “Elevator opened—and it was intimidating. Like going to the Justice Department with all these CBS lawyers running around up there. Here I am arriving with this one little old black lawyer. This huge boardroom runs the length of the floor, could’ve put forty or fifty people into it. Arthur Taylor was sitting at one end, tapping a pencil on the table, and said, ‘Have a seat.’ He had a couple of people beside him, and through the door came a guy with a stack of clippings from newspapers that they were getting from all over the country. There was concern building in the streets, and in black media, and in other media, regarding what was going on between CBS and Stax.”

That concern was deep. The plug was being pulled on an open microphone from America’s African-American heart to the world’s ear. Shirley Brown’s intimate plea was a whisper that, not too long before, could never have been heard. Isaac’s carnal image had been punishable by lynching only a couple decades earlier. Artist after artist, song after song, Stax gave voice to the hearts and minds of a people too long silenced. And with that voice, Stax brought power to its artists and also to its audience. Stax had become the song of a nation. And as Al sat in that huge office high above Manhattan, all of that newfound freedom won with blood and grit was at stake. Columbia cared not a whit about the message. It heard only the cash register. Columbia wanted the sales. Stax was fighting for its voice, its life, and the voices and lives of its people.

Al continues, “Arthur Taylor said, ‘Al, I’m not going to argue with you the merits of your antitrust suit. We just have more time than you and more money than you.’” However daunting the scene may have been, Al had the serenity that comes with faith in his position. “I said, ‘Arthur, there’s no question that you have more money than me but time I question, because I’m not giving up on this.’” If Al was thinking about the hundreds of people who worked for Stax, he must have determined that there was no hope in resolving the issue with Columbia, no hope in retaining their employment by making peace here, because Al didn’t stop; he kept right on going, delivering the goods to the big man on the top floor, saying, “Between me and you, you can call this World War III.” With that statement, Mr. Taylor’s hand stopped tapping that pencil. The room got quiet, and for a moment it seemed that all sound everywhere had stopped. The two executives were eye to eye, physically locked by an unseen tension. The hand holding that pencil clenched, the knuckles getting white, and the silence was torn—SNAP—by the angry breaking of that pencil. Arthur Taylor stood and exited the room.

The wrath of CBS, Inc. was discharged upon Stax. “After that,” says Al, “I grew to appreciate the power of a corporation like CBS. I didn’t realize that they could reach into offices that one would never have thought they could reach into. And they cut off the spigot. They said, ‘We don’t owe you any money because here’s the product that didn’t sell that we had in our warehouse.’ Several eighteen-wheelers came back to where we housed our goods, returning a substantial portion of all the inventory they had purchased on the same skids they were shipped out on. No more cash flow. We couldn’t pay many of our artists and other obligations. They were knocking us to our knees, breaking our back.”

![]()

In Memphis, elements of the white population, feeling their majority slipping away, began expressing paranoia and fear. Blacks were taking over the schools, taking over the city council, and, at the end of 1974, whites feared they would lose their voice in Washington, DC.

The congressional election in 1974 was an off year. Nixon had been reelected president two years earlier, and no Senate seats were up. There was the House election, and in contention was the Ninth Congressional District, which represented the heart of Memphis. The seat had been held for four terms by Dan Kuykendall, a staunch conservative. After the 1970 census, districts were redrawn and Kuykendall’s, which included Soulsville, represented a significantly larger black population. (It was also renumbered from the Eighth.) His opponent in the 1972 race had been African-American, and while the race was close, Kuykendall won 15 percent of the black vote and had the momentum of Richard Nixon’s landslide to help him retain office.

In the 1974 election, Kuykendall’s opponent was Harold Ford Sr., who’d served two terms in the state legislature. Ford was from a prominent African-American family that ran a funeral home and had a history in politics. He organized a vigorous campaign. He understood the racial fears that ran in Memphis and he sought a wide appeal with statements like “Inflation knows no color.” He campaigned on economic development, which would help everyone. With the redistricting in his favor, and the continued momentum from the Voting Rights Act, Ford organized a rudimentary political machine: phone banks, neighborhood caravans, and a proactive voter registration campaign that included rides to the polling places.

Kuykendall, meanwhile, appealed to the city’s conservative core, evident in his steadfast support of President Nixon even after transcripts indicting him were made public. And he had a problem new to the 1974 cycle, brought on by the recent implementation of busing: White flight from the city to the county and beyond had changed the district’s racial demographic to a larger percentage of African-Americans.

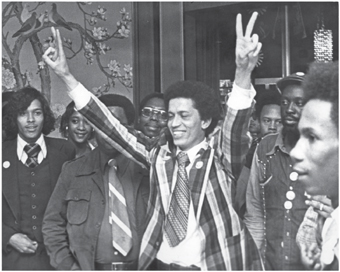

The race grew heated early and as it neared the vote, it was close with an expected Kuykendall win. By nine o’clock P.M. on election night, Kuykendall was ahead by five thousand votes and declared the winner by the major radio and TV stations. But the tally Ford saw on TV didn’t match what Ford’s poll watchers had been supplying him, and he went to the Shelby County Election Commission offices. “For an hour and a half he sat there,” said Election Commission director Jack Perry, “jabbering about ‘Something must be wrong,’ and ‘I know I’ve got the lead.’” As the tally closed, it turned out that six precincts had delivered their ballots but the ballots weren’t among those counted. Soon Ford “and about ten campaign workers found six unopened ballot boxes in the basement of the building.” (Ford was quoted as saying, “We found the reports in a garbage can and sent them up to be counted,” though he later retracted the statement.) Once those missing votes were tallied, Ford was declared the winner. The Shelby County Election Commission was all white; no African-Americans served on it. Harold Ford became Tennessee’s first African-American to serve the United States Congress.

November 5, 1974. Harold Ford becomes Tennessee’s first African-American to serve the United States Congress. (University of Memphis Libraries/Special Collections/Photograph by Jack Cantrell)

Memphis was a city divided. The population was still a majority white, but just barely. The wounds of Dr. King’s assassination had never healed, and the recent busing battles had reopened them. With Ford’s election, many Memphis whites were predicting doomsday scenarios, a revolution of the underclass. Black power frightened them, and they sought ways to take back the power.

![]()

Stax’s troubles had brought the company much unwanted attention, and Al was feeling the backlash against a black-owned company. “Stax was perceived as a white-owned business until they put it in the newspaper that the blacks were involved in the CBS litigation,” says Al, “and that’s when the white community in Memphis started reacting.” Columbia’s stranglehold was keeping any income from Stax, and Union Planters got in the fray by suing both Stax and Columbia. The bank’s suit, resulting from Columbia’s “virtual ownership” of Stax, asked for $10.5 million in damages from the corporate giant, cancellation of the bank’s subordination agreement (so that the bank could then collect its debts before Columbia), and the voiding of a $6 million loan agreement between Columbia and Stax. Union Planters had its own soul to save, and if it had to kill Stax to stay alive, that was basic business; like Columbia, it had millions of dollars invested in the company, though unlike Columbia, the talent of the artists was of no interest to the bank. Union Planters needed the company to thrive, or it needed its assets. Concerned about its reputation in the Memphis community, the bank came to Jim and proposed giving the company to him under some kind of probation. “Jim turned them down right away,” says Whitsett. “He said, ‘I’m with Al Bell on this, I believe in Al Bell.’ And the bank people came back just bewildered. They had to go for the jugular because they did have stockholders, and they had to recoup as much of their loss as they could.”

“It did not surprise me, the posture that that bank took,” says Logan Westbrooks, the Columbia division head. “It was owned and controlled by white men. I grew up in Memphis, I know the racist attitude of whites in the city of Memphis. The moment they became aware that Al Bell was the owner of Stax Records: ‘How dare you, black man, own this company in the city of Memphis!’ It was a vendetta from those white bankers against Al Bell and Stax Records.” Indeed, though Westbrooks would have reason to deflect blame from his company to the bank, his fundamental point remains true: Many white leaders (and followers) in Memphis were uncomfortable with African-Americans gaining ground in society; further, they’d find the idea of the city being represented by African-American culture embarrassing. Business was first, but reputation was not far behind.

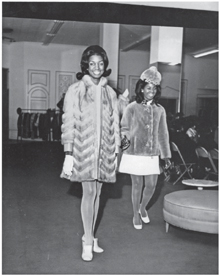

Earlie Biles, Al’s secretary, says, “I think the city saw all these black successful people with gold cars, fur coats, gold jewelry, and fancy this and fancy that, flying here and there—they didn’t understand what was going on.” Deanie Parker, the publicist, concurs: “Union Planters Bank was having very serious difficulties. Being a marketer, I think they were very shrewd. If they could find a scapegoat to position at the center of negative news, and blame their inefficiencies, their ineptness, their shenanigans, on somebody else, then it made a better story for the stockholders and for the customers. And in Memphis, Tennessee, what better target than a record company that’s predominantly African-American that’s making black people wealthy? Where Isaac Hayes is driving around in a custom-made Cadillac that cost more than many white folks’ houses did? And what better examples than Carla Thomas or Shirley Brown, or another artist purchasing a fur coat—cash. We were a victim of the times. Now, that said, Stax Records was not perfect. We were like any business, making the best practical decisions that we could, and we were risk takers as well. And the industry itself was changing.”

Earlie Biles, left, and Bettye Crutcher. (Stax Museum of American Soul Music)

While the label may have felt persecuted, the fact of its indebtedness to the bank remained, along with its lack of collateral, its impenetrable accounting, and the lawsuits against it. These were plenty enough reasons for the bank to pursue it vigorously. “I considered Bill Matthews in all respects an honorable, truthful person,” says attorney Wynn Smith. “As far as racism is concerned, my impression was that he didn’t recognize but one color, and that was green. I never saw any evidence of his being racist, and I was never aware of any impetus to go after Stax for any racial reason at all.”

Each side seems to see what it wants to see, but no matter what the disagreement was about, Al shares an insight that gets to the core of how the disagreement was handled, a reality about the times: “I know that if I had been a white man, Matthews would have dealt with me differently. Assets were sitting here. The language would have been different. The discussion would have been different.” Such a discussion with Al, for example, could never have taken place on the golf courses of several prominent Memphis country clubs that were still “exclusive”—forbidding membership to blacks and Jews among others. American society in general, and Memphis society in particular, was undergoing a transformation, trying to make a paradigm shift from a hundred or more years of institutional racism to new equality. It would be harder for those of the older generations. As progress dragged across stasis, the friction was burning Stax.

Tim Whitsett, who had become president of East/Memphis Publishing, remembers an embarrassing proposal made at a meeting between the bank and the publishing company’s writers. “Matthews pandered, especially to our black writers,” says Whitsett. “I was in the room, Eddie Floyd, Mack Rice, all of our writers.” Matthews proposed that, in lieu of payments to the writers, which would be temporal, that the publishing company fund a statue of Dr. King, which would be lasting. “The writers are going, ‘Hey, man, we’d rather get paid.’ It was so embarrassing. I felt a general uproar bubbling.”

In November 1974, Tim Whitsett was in his office when a Matthews henchman named Roger Shellebarger entered. “He announced that the Union Planters Bank was taking control of the publishing company, and the first thing they’re gonna do is move us downtown next to Union Planters. It was totally astounding.” Stax had defaulted on payments against which the publishing company was the collateral, and the bank was exercising its right to assume control. Jim Stewart had recently met with Whitsett and told him to go along with whatever the bank might say, but Whitsett was not expecting a new boss. Publishing is the music business’s constant cash flow, and diverting Stax’s stream would wither the company.

Even among the inner circle at Stax, this loss was a surprise. Few saw evidence that the situation was turning so calamitous. “All the news was hitting the trade magazines,” says Whitsett, “and I could not fathom the company going under. It was like the Bank of England or the Rock of Gibraltar.”