VII

On the morning of the accident, Huda Dahbour left her Ramallah apartment and struggled through the wind and rain to meet her staff at Clock Tower Square. A fifty-one-year-old endocrinologist and single mother, she managed a mobile health clinic run by UNRWA, the UN organization for Palestinian refugees. She had been at the job for sixteen years, working at UNRWA’s Jerusalem headquarters in Sheikh Jarrah until Israel made it impossible for her to enter the city. Now she treated patients in a mobile clinic in the West Bank.

Three members of her medical team joined her at Clock Tower Square. They were scheduled to make their regular visit to the Bedouin encampment of Khan al-Ahmar. Getting into the minibus, they greeted their driver, Abu Faraj, a Bedouin man with white hair and a white mustache. In addition to driving, he served as a sort of cultural advisor, helping Huda and her team navigate local rivalries and tribal customs.

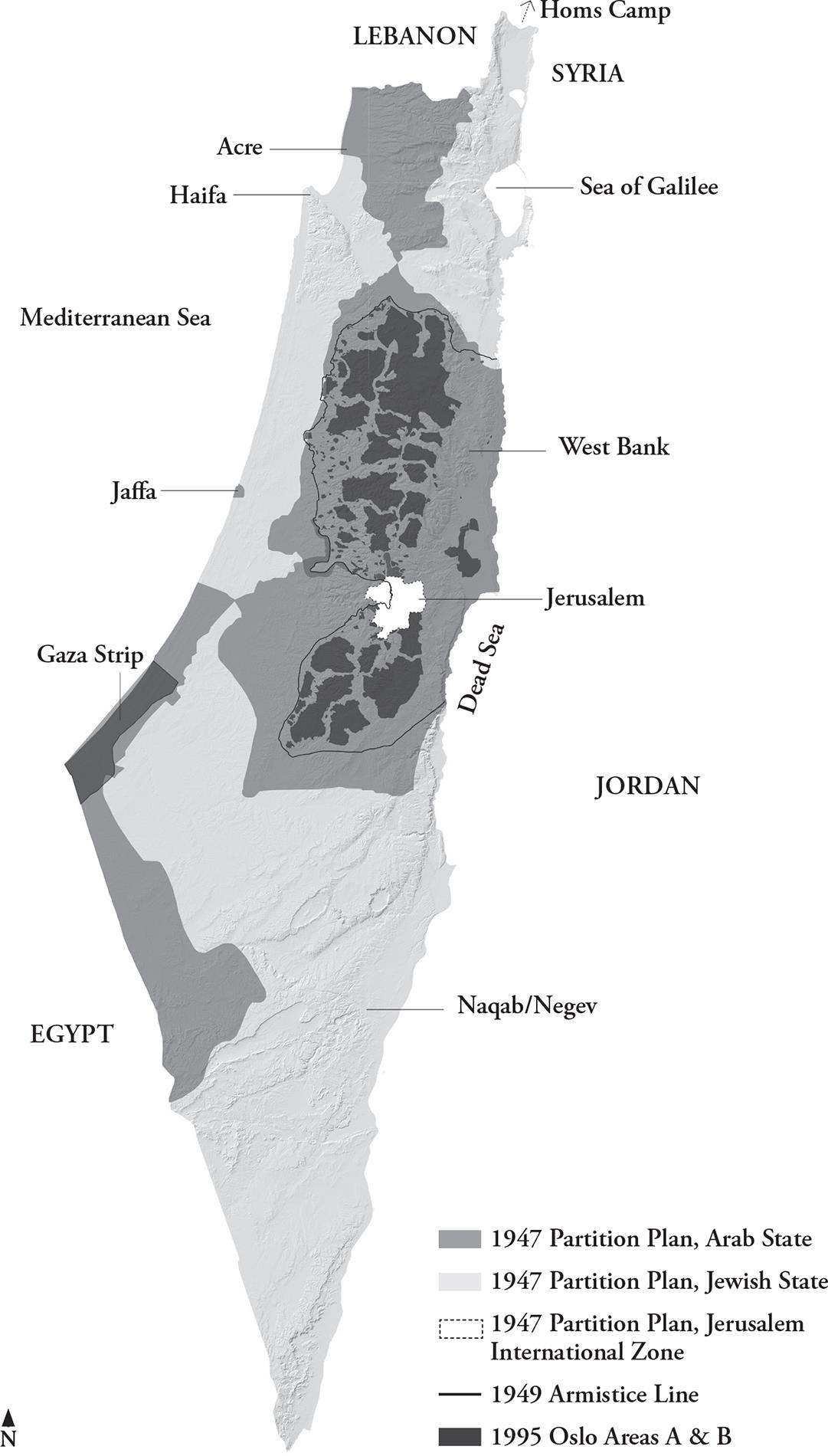

Khan al-Ahmar was home to Bedouin of the Jahalin tribe who had been expelled from the Naqab in the years after the founding of Israel. Most of the tens of thousands of Naqab Bedouin had been forcibly displaced in 1948, fleeing to the West Bank, Gaza, and neighboring countries. In the four years following the war, Israel expelled some seventeen thousand more. In total, around 85 percent of the population was removed. Those who remained in the Naqab were corralled into a reservation, the siyaaj, or fence, while their land was confiscated. Along with the majority of Israel’s Palestinian citizens, they lived for eighteen years under the rule of a military government, which imposed curfews, travel restrictions, a ban on political parties, detention without trial, and closed security zones.

Forced at gunpoint to leave the Naqab and cross into the West Bank, the Jahalin Bedouin made their way north to the desert hills outside Jerusalem. There they were expelled once again to make room for the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim. When they reached nearby Khan al-Ahmar, they requested permission to stay there from the land’s owner, Abed’s grandfather. He initially rebuffed them. Abed’s family, like many in Anata, distrusted the local Bedouin. Some of them encroached on other people’s property, took handouts of UN food and made a business of reselling it, and ignored bills for municipal services, claiming that their Bedouin practices did not recognize bourgeois activities like paying taxes.

They squatted on Khan al-Ahmar anyway. Eventually, Abed’s grandfather came to see the value of their presence on his land: since he wasn’t allowed to access it himself, having the Bedouin there made Israeli expropriation more difficult. Settlers considered the encampment an eyesore, and Israeli planners wanted the area cleared of Palestinians. When Israel issued demolition orders for the rusted tin shanties and schoolhouse made of car tires, Abed’s family provided documents showing that the Bedouin had been given permission to live on the Salamas’ land.

Huda did what she could for the impoverished Bedouin. Though forbidden to treat their goats or take them in UN vehicles to buy provisions, she did so regardless. At the UN, she was known for flouting the rules when her conscience dictated it. Despite repeated warnings from her bosses against engaging in political activity, Huda brought her staff to protest Israeli attacks on Gaza, and on one occasion she took them to give flowers to women political prisoners being released from Israeli jails. After UNRWA made cost-cutting changes that limited prenatal treatment to patients considered at risk, Huda gave the designation to every pregnant woman she encountered. Confronted by her supervisor, she proudly admitted her transgression and vowed to carry on doing it until the regulations were changed.

LEAVING CLOCK TOWER Square, Abu Faraj called the sheikh of Khan al-Ahmar to confirm that Huda and her team were on their way. The villagers had prepared a ceremonial welcome tent to greet them before the UN staff treated the women, children, and men. Heading south, the team sang along, as they always did, to Fairuz, Huda’s favorite singer. After they stopped to pick up the data entry clerk at the Qalandia refugee camp, the pharmacist, Nidaa, said she felt nauseated. Huda thought she looked pale. A young mother of two small children, Nidaa was several months pregnant with a third. Huda told Abu Faraj to pull over so they could get her some food. They turned off at a roundabout and entered a-Ram, an urban area facing the settlement of Neve Yaakov and surrounded on three sides by the separation wall. It was cold, wet, and dreary. They drank tea and ate ka’ek with zaatar and falafel. Now running late for Khan al-Ahmar, they exited a-Ram for the Jaba road and came face-to-face with a horrific sight: a school bus flipped on its side, its doors against the ground, its front engulfed in flames.

The Jaba road was originally built to take settlers to and from Jerusalem without having to enter Ramallah. It was one of many such bypass roads, designed to reduce commute times for the settlers, give them a sense of safety, and create the illusion of a continuous Jewish presence from the city to the settlements. After Israel built new bypass roads, this one came to be used mostly by Palestinians.

It had been carved through an escarpment, forming a deep chasm with tall rocky cliffs on both sides. The village of Jaba perched atop one cliff; a-Ram was on the other. The road had two lanes heading toward the Qalandia checkpoint, and one going in the opposite direction, toward the Jaba checkpoint, and there was no center divider. The single eastern lane served as the main route around blocked-off Jerusalem for some 200,000 people, but the Jaba checkpoint was not permanently staffed. Soldiers were there to stop cars mostly during the morning and evening commutes to reduce the flow of Palestinian traffic onto a road shared with settlers. So at rush hour, the Jaba road was clogged with a long line of Palestinian buses, trucks, and cars. As drivers neared the bottleneck, only minutes after having escaped the maddening gridlock at Qalandia, some would overtake slow-moving vehicles by veering into a lane of opposing traffic. This had caused so many accidents that the artery came to be called “the death road.”

Huda asked Abu Faraj to pull over. People were exiting their cars and converging around the overturned school bus. Because the road was wet and oily, Abu Faraj stopped the van sideways to prevent oncoming cars from sliding into the gathering crowd. Huda and her team jumped out and rushed to the front of the bus. Behind it they could see an eighteen-wheel trailer truck that had come to a diagonal halt across two of the road’s three lanes.

Salem, one of the onlookers, lived just a few hundred feet away but he spoke in the heavily accented drawl of a Hebronite. He had kept his children home that morning because of the pelting rain and heavy fog. In all his thirty-eight years, he had never seen rain like that. He was on his way to work when he saw the overturned bus, stopped his car in the middle of the road, and ran toward it.

Huda called to Salem and a few other men nearby to get the driver out, since he was close to the fire. As they began to pull at him, he yelled to them to save the children and their teachers. Until that moment, Huda hadn’t realized there were children on the bus. Her colleagues would remember the children screaming, but Huda either erased the memory or blocked out the sound. Together with Salem, they yanked at the driver, whose body was stuck and his legs aflame. When they finally managed to free him, the rain doused the fire on his legs.

They laid him at the side of the road, the smoke still rising from his knees, and rushed back to the front of the bus to reach for a teacher, who had been sitting behind him. While they were grabbing her, she shouted that they should leave her and save the children. At this, Nidaa began to convulse and shriek. Huda hurried her back to the UNRWA van and told her not to get out.

Abu Faraj, in the meantime, was directing traffic, keeping a path clear for the eventual evacuation of the wounded. He now ran past the burning bus and splayed semitrailer to the Jaba checkpoint a few hundred feet down the road, thinking to beg the soldiers there to help with the rescue. The smoke was visible at the checkpoint, but the soldiers, who seemed frightened, shouted at him to stay back and not come any closer.

At this point, the fire was too fierce to continue pulling anyone out from the front of the bus. But it had not yet reached the back, where, as far as Huda could see, most of the children were crammed. Salem wanted to break the rear windows to get the children out. Huda wasn’t sure it was a good idea. No one had a better one, though, and there seemed to be no soldiers, police, fire trucks, or ambulances on the way, despite people in the crowd who kept frantically phoning the Israeli and Palestinian emergency services. One of Huda’s team even called a relative who worked in the Palestinian parliament.

Huda and the others close to the bus agreed that Salem should smash the rear windows using a small fire extinguisher, which one of the bystanders had brought from his car. The moment the back window shattered, Huda heard a whoosh of oxygen and saw the flames around the bus shoot up into the air. The fire now doubled in height, sending up thick, black plumes of smoke that rose above the cliff.

Huda watched in shock as Salem crawled into the burning bus. He could hear the kindergartners crying and screaming. Some of them tried to climb up on the overturned seats and jump to the windows above them. Two teachers managed to escape through the smashed windows and brought several of the children out with them.

Ula Joulani, one of the teachers, was on the trip with her nephew Saadi, who was in her kindergarten class. She was like a second mother to Saadi. That morning, as on every weekday, Ula had driven to her parents’ home, where Saadi and his family lived. Complaining about the terrible weather, her mother didn’t think Saadi should go on the trip. Ula laughed, asking her mother if she wanted a refund. Ula had paid the fee for one of her students, an orphan, and had promised to take care of another child, the son of a friend, who, like Saadi’s grandmother, had reservations about the outing.

After Ula made it out of the burning bus, she heard the trapped children calling her name. So she followed Salem back inside, the only other person to do so. Salem, hunched in the bus, had managed to open some of the side windows. He and Ula lifted the children up and through the back of the bus as Huda and the others formed a line, handing the kindergartners down one by one. High above the road, at the top of the cliffs, dozens of villagers had gathered from Jaba and a-Ram. Some of the Jaba Bedouin brought large tanks of water that they poured onto the flames and through the open bus windows, helping to keep Salem and Ula from burning. At the side of the bus, the crowd tried to hose them down using small fire extinguishers.

Ula and Salem managed to rescue dozens of the children. As they progressed toward the front of the bus, where the flames were strongest, the children they reached were in worse and worse shape. Some were charred from head to toe. They were placed on the road face up, their knees bent up to their chests. Had he not known otherwise, Salem would not have recognized them as human. One girl, who was blackened all over, had been set on the ground with the dead children when a nurse working with Huda saw that she was still breathing. Huda and the nurse lifted her up and put her in the backseat of a car that would take her to the hospital.

The stench of burned hair and flesh was overpowering. Huda had read somewhere that smell was the sense most strongly linked to memory. Perhaps that was why, standing there amid the carnage, she was taken back to the worst day of her life.