XII

On the eve of the accident, Radwan Tawam was sitting in his living room in Jaba when the phone rang. It was his uncle Sami, who owned a small bus company where Radwan worked as a driver. Could Radwan transport the kindergartners from Nour al-Houda on their class trip the next morning? Radwan was close to Sami, more like a brother than a nephew, and he always wanted to help, but he hesitated. From his home near the top of the hill in Jaba, he could hear a ferocious wind and see dark clouds overhead. A terrible storm was coming, and the local roads weren’t built for such weather.

Early the next day, Sami kept calling and Radwan kept ignoring the calls. He wouldn’t be strong-armed into driving in this weather. But not long after the last call, Sami pulled up outside Radwan’s house, driving a beat-up, twenty-seven-year-old bus with fifty seats. He got out, walked past the olive and fig trees in the front yard, perpetually covered in dust from explosions at a nearby limestone quarry, and rapped at Radwan’s door. Reluctantly, Radwan agreed to go.

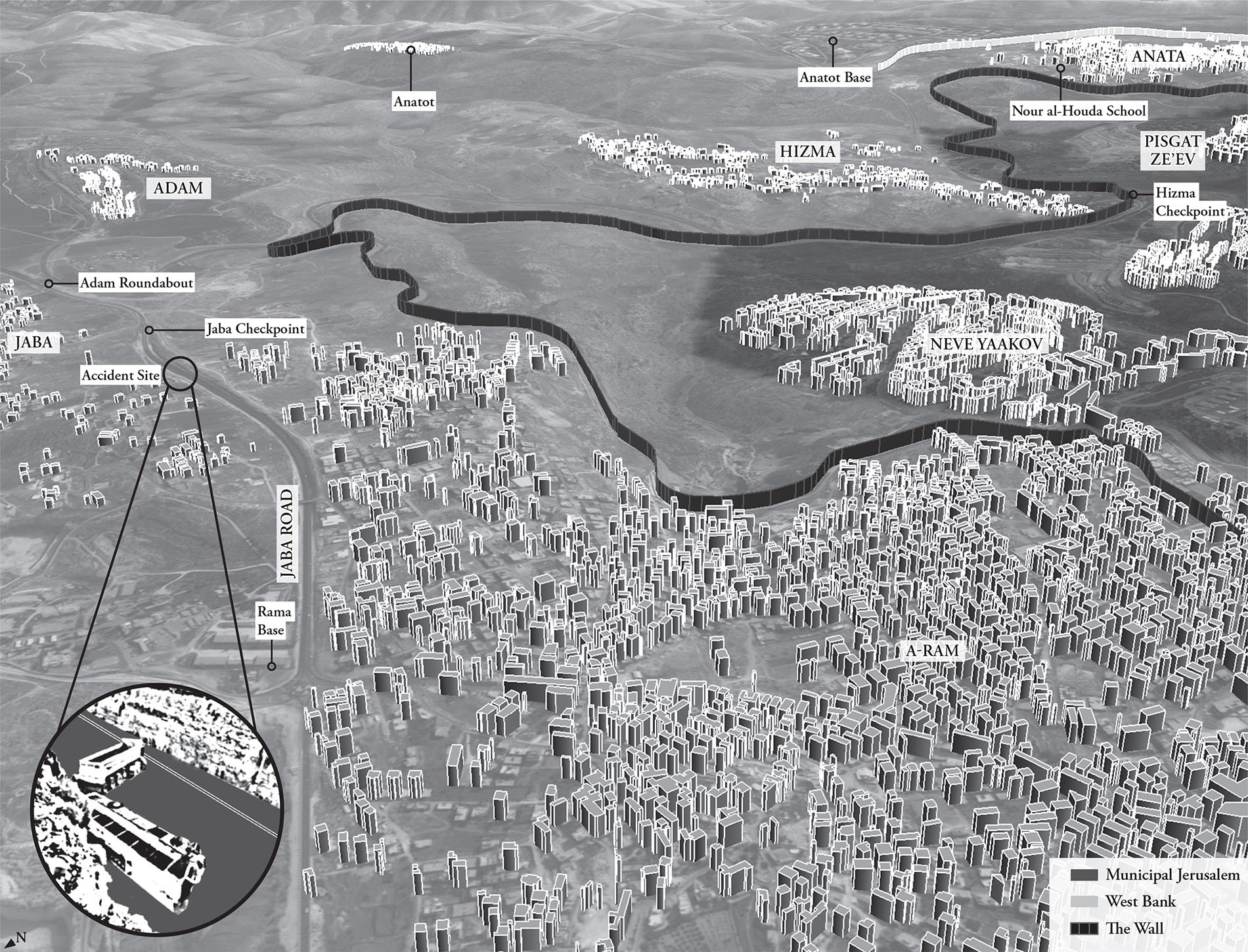

He drove away from the house, slowly steering the bus downhill through Jaba’s narrow roads, which overlooked Tawam family land that had been seized for the settlement of Adam. During the Second Intifada, Israel had closed the main entrance to Jaba, blocking it with mounds of earth that had since become a permanent barrier. To get to Anata, Radwan and Sami first had to drive in the wrong direction, into a-Ram, then double back toward the checkpoint on the Jaba road.

At Nour al-Houda, Sami jumped out, telling Radwan he had to take care of some other business. Radwan saw a line of children waiting to board another bus, also one of Sami’s, which was now overfull. So the second driver told some of the kindergartners to get off his bus and board Radwan’s instead. With the rain coming down and the teachers herding damp, excited children on and off buses, no one thought to revise the passenger lists.

The students piled on and pushed past Radwan, their backpacks too large for their small bodies. As the bus left the school, the separation wall visible through the windows, Radwan turned on the television hanging above the aisle and played some cartoons for the children to watch. When he reached the Jaba checkpoint, the rain turned heavy and loud. The creaky bus was slow, so Radwan stayed in the right lane, allowing other cars to pass as he wended his way up the hill. At 8:45 A.M., less than a minute after crossing the checkpoint, the bus was struck by a massive force. Radwan blacked out.

A video taken by one of the onlookers shows the scene in the final minutes of the rescue, just before the arrival of ambulances and firefighters. In it, people are rushing to the overturned bus, which is reduced to a burning chassis, as tall red flames shoot into the air and the sky turns black with great swells of smoke rising above the rocky cliff. A woman is heard shrieking. Someone yells, “There are kids inside!” And then, “Fire extinguishers! Fire extinguishers!” A number of men fetch small fire extinguishers from their cars, and others are running with water bottles, pouring them into the blaze to no effect.

The flames grow. One man paces in a circle, gripping his face with his hands. Another hits himself on the head. A third, his fire extinguisher emptied, storms away from the bus, yelling, “Where are you people? Dear God!” He then lifts the extinguisher above his head and slams it to the ground. A small corpse lies in the road. “Cover him, cover him!” a voice calls, and then, “Where are the ambulances?” “Where are the Jews?”

Two men run forward holding a child. “The boy is alive! Quick! He needs resuscitating!” Someone else points to an adult figure on the ground. “Bring a car! This man is alive!” A blurry figure jogs away from the bus carrying a girl, her hair in braids fastened with pink ties. She seems unhurt and in a kind of trance, not answering when the man sets her down and says, “Do you need anything, dear?” More children enter the screen, one by one, and are taken to the cars nearby. Through the smoke comes the sound of wailing.

NADER MORRAR WAS the first paramedic on the scene. He’d received a call from dispatch at 8:54 A.M. reporting that a bus had rolled over on the Jaba road. The caller did not say whether the bus was empty or not. Nader knew the accident site—he had heard people call it “the death road.” He assumed Israeli ambulances would get there first, since the road was in Area C, the more than half of the West Bank that after Oslo had remained under total Israeli control, governed by its army, patrolled by its police, and within the jurisdiction of its emergency services.

To get to the site from where he was stationed at the Palestine Red Crescent headquarters in al-Bireh, Nader would have to drive through the walled-off neighborhood of Kufr Aqab, which in heavy rain could flood so badly that cars would be under water. Then on to the Qalandia checkpoint and the pileup on the single eastbound lane leading to the accident, about four and a half miles all told. In this weather, the journey would usually take around a half hour.

To his surprise, he made it in ten minutes. More surprising was that there were no Israeli emergency services, no army, no police. By the time Nader arrived, most of the injured children had been evacuated in cars, but he did not know that. He could see people up on the cliffs overlooking the road, waving their arms and shouting. To his left was the overturned school bus, still burning. Several bodies lay on the ground. “Mass casualty incident,” Nader radioed to headquarters, calling for backup.

Nader moved with some discomfort. He had been a student at Birzeit University during the Second Intifada, when Israel had shut the main road to the school. At a protest calling for Israel to reopen Birzeit, a soldier shot Nader in the leg, fracturing his femur. It took two surgeries and a year of rehabilitation for him to recover, and he had dropped out of school. Inspired by the medical team, he enrolled to become a paramedic. A decade later, working for the Red Crescent, he was again shot in the leg by Israeli forces.

He had barely stepped out of the ambulance before people rushed at him to take the dead. The fire was now so intense there was no way to approach the bus. Two adults were lying on the asphalt, each with what looked like third-degree burns and both struggling to breathe. One was a teacher; the other was Radwan, the bus driver, who had multiple fractures and was severely burned. Nader and his driver loaded them onto the ambulance for immediate evacuation. The only option was to take them to Ramallah—if they attempted to go to Jerusalem, they could waste valuable time or even lose a patient while waiting at the checkpoints for permission to carry the victim on a stretcher to an Israeli ambulance on the other side.

For Nader, in a crisis, all the different legal statuses of Palestinians were irrelevant. The only thing that mattered was whether the patients were Palestinians or Jews. He could never, under any circumstances, bring someone Jewish to a Palestinian hospital. But he had brought Palestinians with Israeli citizenship to West Bank hospitals—and, for all he knew, he was now ferrying two more. As the ambulance rushed to the medical center in Ramallah, passing the Qalandia checkpoint with sirens blaring, Nader treated both Radwan and the teacher, giving them oxygen and stemming the loss of blood while trying to stay focused through their cries.

ELDAD BENSHTEIN HAD woken up early at his home in Tekoa, a settlement in the dry yellow hills southeast of Bethlehem. He had to be in Jerusalem’s Romema neighborhood at 7:00 A.M. to start his shift at Magen David Adom, or Mada, Israel’s national emergency medical service. Nestled at the foot of Herodion, the mountain where King Herod the Great built a palace fortress in his name, Tekoa offered spectacular 360-degree views of the West Bank. To Palestinians, the flat-topped peak was known as Jabal Fureidis, Little Paradise Mountain.

Eldad hadn’t been born in Tekoa, not even in Israel—he had moved at age eleven from Moscow with his parents, both doctors. In Russia they had worked on ambulance crews. Eldad thought it was more exciting to be a paramedic than a doctor, and at sixteen he began volunteering at Mada, years before he joined the staff. He was now thirty-three and had the look of a biker, with an earring, a shaved head, and a goatee.

His ambulance was on the way to a call in Pisgat Ze’ev, the settlement next to Anata, when the dispatcher radioed that they should change course and head to an accident on the Jaba road. Eldad knew only that the crash involved a truck. There was no mention of children or a school bus. The rain was coming down hard. With sirens on, the ambulance sped to the Jaba checkpoint, where soldiers waved them through. They first came to the giant semitrailer splayed across the road and saw fire and smoke rising behind it. As the driver squeezed around the side of the semitrailer, crowds of Palestinians up on both ridges overlooking the road shouted and gestured at them to advance. There was the bus in flames, flipped over, and there were several dead children laid out on the ground. Jumping from the vehicle, Eldad yelled in Hebrew, “Is there anyone on the bus? Anyone on the bus?” Half the people didn’t seem to understand and the rest were too distressed to notice him.

It was 9:09 A.M., twenty-four minutes after the bus had crashed. Eldad was the first Israeli on the scene. Just as he got there, an army ambulance drove in from the opposite direction, coming from the Rama military base less than a mile up the road. But there were still no fire trucks in sight. Eldad went back to his vehicle to call in a mass casualty event but couldn’t tell if the transmission had gone through. He tried his cell phone—no signal—then urged the army doctor to call Mada through his IDF communications system. The fire in the bus was raging and there was no way to enter it. Eldad began talking to the army doctor about triage, though with every passing moment he was more certain that any passengers left on the bus would be dead by the time the firefighters arrived.

Several minutes later, he saw Palestinian fire trucks coming from the direction of the Rama base and then he heard sirens. When more Mada ambulances pulled up—now thirty-four minutes after the crash—he asked if anyone had got his radio messages. They had, which meant additional ambulances were en route. One of the Mada drivers, an old, experienced hand, said they should position the ambulances in a single file, facing Adam, to leave room for other emergency vehicles and be ready to speed to Jerusalem as soon as they had the injured on board.

Eldad stood in the rain, watching with dread as the Palestinian firefighters extinguished the inferno. The whole thing took no more than fifteen minutes, though it felt much longer. When the last of the flames were doused, the firefighters climbed into the skeleton of the bus. The call rang out: no bodies. Eldad began to breathe again.

AFTER HE HAD carried the last child off the bus, Salem felt faint and nearly passed out. He didn’t know what was wrong with him, but he didn’t feel as if he could move his body. The arrival of the Palestinian firefighters seemed to revive him, and Salem began to yell. “You’re an hour late!” he screamed. “You killed them! You killed our children!” He said it over and over, to every paramedic, firefighter, and police officer, whether Palestinian or Israeli.

Salem was taken to an Israeli ambulance to receive first aid and was given a shot to calm him. At first, he didn’t realize where he was. As soon as he did, he ran off. Then he refused to sit in a Palestinian ambulance. “You killed these children!” he wailed again. To everyone and no one, he continued shouting that the Palestinian and Israeli rescue workers were child killers.

Israeli soldiers were at the site by this point, and one of them approached Salem. In a mixture of Hebrew and Arabic he demanded that Salem explain his accusation. The Palestinians at least had the excuse of heavy traffic from Ramallah, Salem said. And they weren’t allowed to have police or fire trucks in the towns close to where the accident happened—they weren’t even allowed to be on the Jaba road without Israeli permission. But still they’d arrived first. The Israelis had no excuse.

All Salem’s customers at his tire repair shop were Israelis. He’d been inside their settlements for his work and he knew they had ambulances and fire trucks. The police headquarters in the Sha’ar Binyamin industrial zone was just a mile and a half away. There was a fire truck and ambulance in Tel Zion—the big ultra-Orthodox settlement above Jaba. The fire station in Pisgat Ze’ev was two miles’ distance as the crow flies. He’d seen ambulances parked in Adam, less than a mile from here—so close you could see the entrance from the burning bus. The Jaba checkpoint was even closer, just down the road, near enough to smell the smoke. There was a water tank there, and the soldiers surely had fire extinguishers. How come the Jaba Bedouin managed to haul their water tanks to the cliff, but not a single Israeli soldier showed up? What about Rama, the military base? Where were the soldiers and medics and jeeps and water tanks and fire extinguishers? If it had been two Palestinian children throwing stones on the road, the army would have been there in no time. When Jews are in danger, Israel sends helicopters. But a burning bus full of Palestinian children, and they show up only after every kid has been taken away? Salem concluded. “You wanted them to die!”

The soldier shoved him, and Salem pushed him back. Within seconds, a half dozen soldiers were beating Salem on the back of the head until he fell to the ground, and then he was punched and kicked. When the soldiers had finished with him, someone got his phone and called his wife to come pick him up. After risking his life to rescue the children, Salem spent ten days in the Ramallah hospital, with damage to both kidneys and dislocated discs in his spine.

For many months, he would wake up at night screaming, begging his wife to smell his arms, to smell the reek of death on his flesh. When he washed his hands, he insisted he picked up the whiff of burning bodies. Without warning he’d break into tears. His wife took him to a psychiatric clinic in Bethlehem. He suffered from memory lapses after the accident, and blamed them on the beating he got from the soldiers. In truth, he was grateful for the bouts of amnesia. They were the only thing keeping him from going insane.

THE MOMENT ELDAD Benshtein realized he wasn’t needed, he got away from the site as fast as he could. He stopped the ambulance near Adam to smoke a cigarette and calm himself before heading back to Jerusalem. The scene he’d left—the burning smell, the charred bodies, the wailing crowd, the bones of the bus—had taken him back to his first days as a volunteer, during the 1990s, and the string of suicide bus bombings, which he had privately named the time of the flying buses.

Eldad returned to Mada headquarters and was directed to transfer one of the children from Hadassah’s Mount Scopus complex to its campus in Ein Kerem. The emergency room looked like a war zone. Families blocked the hallways, holding injured children who had been brought by car and were waiting to be seen. He had been sent to pick up Tala Bahri, a girl from Shuafat Camp. He couldn’t have known, but she was considered one of the most beautiful girls in the school, with large amber eyes, long curly hair, and an irresistible smile. Now she was unrecognizable—severely burned, unconscious, anesthetized, and intubated for mechanical lung ventilation.

On the way to Ein Kerem, Eldad heard on the radio that Mada ambulances were heading to Qalandia to receive patients for transfer from Palestinian ambulances, which were not allowed past the checkpoint. Most of them were injured children coming from the hospital in Ramallah because they needed better care in Jerusalem. It was only then that Eldad began to grasp the scale of the tragedy. He brought Tala to the shock trauma unit and left the ER, stepping into a small garden on Hadassah’s grounds. There he stood alone and wept, for Tala, for the dead children, for the suicide bombings all those years ago.

As Eldad returned to the ambulance, a TV news crew approached him for an interview. His wife was at home in Tekoa watching the news and saw her husband, who seemed confused, struggling to find words. She had never seen him look so lost.

ELDAD HAD LEFT the accident just before a stream of soldiers, police, firefighters, and reporters descended on the site. One of the last rescue workers to show up was Dubi Weissenstern. He was used to coming in at the end. Dubi ran logistics for ZAKA, the ultra-Orthodox, or haredi, volunteer organization that collects the dead for burial. Its volunteers in their white coveralls would fan out over a disaster zone, combing the area for victims and scattered body parts. Nearly every one of ZAKA’s Jerusalem volunteers was haredi, driven to fulfill the Halakhic commandments to honor the dead and bury a person intact, as they were at birth. Dubi was among the dozen paid staff members.

He had grown up in Jerusalem, studying at a yeshiva in Mea Shearim, among the oldest Jewish neighborhoods outside the Old City. Home to the most insular, stridently anti-Zionist, and predominantly Hasidic sects, its residents deem the State of Israel secular and reject its creation as a desecration of Jewish law. Dubi’s family was a little more mainstream, and Dubi himself looked quite modern. He wore the standard uniform of dark slacks, white dress shirt, and black kippah, but he kept his beard in a stubble, styled his sandy blond hair like a businessman, and had cut off his sidelocks many years ago.

As a teenager, Dubi had flirted with the possibility of living a very different life. He was what was called a shabaabnik, a little wild, barely following the Halakha. He left the yeshiva and only half-observed Shabbat, the Sabbath. He even wanted to be a pilot in the Israeli air force, which would have made him an outcast among haredim and estranged him from his family. His parents said it was time to choose—he couldn’t keep one foot in the haredi world and one foot out. Dubi jumped in, though it was not a decision made from faith. He didn’t want to lose his parents.

His father and brother were volunteers at ZAKA, and Dubi joined them. They worked closely with the Israeli police and were often the only other people at a murder scene, seeing the evidence and overhearing the detectives do their work. Dubi had obtained a high security clearance and the status of a civil guard under the police. He had started work in logistics because he was afraid of seeing the dead. His best friend had hanged himself, and Dubi had been the one to find the body. He fainted at the sight and couldn’t sleep for three days. As the logistics manager, he didn’t go to most disaster scenes, only to mass casualty events, where he’d coordinate the volunteers and equipment.

The core principle of the work was k’vod hamet—respect for the dead. Five volunteers were assigned to each victim, enough to carry the stretchers or body bags without dragging them on the ground. Sometimes they retrieved just body parts. Dubi had been at the aftermath of suicide bombings, where ZAKA would spend many hours at the scene, trying to collect every last scrap of remains. On days like those, he called himself a janitor.

The bombings in Machane Yehuda, the Jerusalem market, were particularly hard. The volunteers were unable to distinguish the bombers from the victims. After one suicide bombing, Dubi and his volunteers were at the Abu Kabir morgue to deliver the remains of fifteen people when the pathologist told them they had brought sixteen hearts. Dubi sometimes had nightmares of his wife and children exploding.

It was raining when he got the call over the radio about an accident near Adam. He was ready for snow, wearing hiking boots, a navy-blue sweater, and a tan winter coat. Though he didn’t know whether the victims were Jews or Arabs, he understood that it was a major collision involving dead children. He was in no rush to get to the site, not until he knew the number of victims and could decide how much equipment his colleagues would need. He drove from the ZAKA headquarters at the entrance to Jerusalem and stopped at the storage facility beneath the settlement of Ramat Shlomo, picking up stretchers, bags, cleaning equipment, and white coveralls. If the coveralls got blood on them and one of the victims was Jewish, they would need to be buried with the dead.

When he arrived at the site, the road was lined on both sides with emergency vehicles, army jeeps, and police cars, leaving an open path through the middle. Dubi took in the tractor trailer, the burned-out bus, the children’s backpacks. Even with all the carnage he had witnessed, this crash was one of the worst. He knew he would look at his children leaving for school and think of the small, scorched backpacks.

Bentzi Oiring, the head of ZAKA in Jerusalem, had got there before Dubi. Bentzi was a giant bear of a man, with a large belly and a bushy gray Santa beard. With his glasses, black felt kippah, black vest over his tzitzit and white collared shirt, he seemed dressed more suitably for the yeshiva. He had worked at ZAKA since its founding in 1989 and estimated that he had been at the scene of 99 percent of the bombings in Jerusalem. Far more than Dubi, Bentzi was an anti-Zionist—he’d have no problem living under a Palestinian prime minister, so long as he wasn’t persecuted and coerced into changing his lifestyle, as secular Zionist leaders tried to do.

To Bentzi, few things were as challenging as handling the dead. ZAKA stayed with the bodies for hours and sometimes days, speaking with the police, the pathologists, and the members of the chevra kadisha, who ritually purify Jewish corpses before burial. The hardest work was informing the relatives. Worse than seeing a dead person, Bentzi thought, was watching a family crumble before you. Those people never forgot his face, the face of the angel of death. One day in a haredi neighborhood of Jerusalem, a father noticed Bentzi and ran across six lanes of traffic to escape him.

After Dubi brought large blue cases of equipment, he and Bentzi and half a dozen volunteers put on latex gloves and neon yellow ZAKA vests with silver reflective stripes. Dubi stood atop an army jeep beside a soldier so that he could see above the crowd and call out instructions. Bentzi and the other ZAKA workers combed the bus, truck, and pavement for body parts. They found nothing. Dubi went after them to double-check. Someone suggested that there could be corpses trapped under the side of the bus, so they waited an hour for a crane to come and lift it.

Unlike Bentzi, Dubi refused to speak with families of the dead. He said he wasn’t an actor and couldn’t lie to them about what their loved ones had looked like. It was natural, he thought, that the death of Jews had more of an effect on him than the death of Palestinians—any Jew claiming otherwise had to be lying; it just wasn’t the same. But even a remote tragedy took its toll. The children on the bus were part of what Dubi called a distant circle of connection, yet those backpacks had brought them closer—he could imagine himself in the place of the parents from Anata and Shuafat Camp. All deaths are devastating, even when they are expected, even when someone’s sick and they have a fifty-fifty chance of surviving. But to go from zero to one hundred, that was something else. Any parent would be torn in two.

COLONEL SAAR TZUR was close to the scene of the accident, near the Qalandia checkpoint, when he first got word of it. A rising star in the IDF, he was commander of the Binyamin Brigade, which covered the central West Bank, including the greater Jerusalem region. After spending many years posted in the area, he knew it well and was now headquartered at the Beit El base at the edge of Ramallah. If anyone asked him how long he’d served in his current position, as commander, he’d say four years, not two, because he lived at the base and barely slept. On a typical day he went to bed at 5:00 or 6:00 A.M. and woke up at around 9:00 A.M. He rarely saw his wife and three young children.

The Qalandia checkpoint was a place he could never forget. In 2004, he had pulled up in his jeep at the same time as a man from Jenin, who had been sent there by Fatah’s al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades with a bomb. When the man saw a group of Border Police and soldiers, he remotely detonated the bomb. Saar had just gotten out of his jeep as it exploded, sending him and three Border Police flying backward. Saar was flung thirty feet through the air, slamming his head on a car. The police officers were seriously injured. The only people killed in the blast were two Palestinian bystanders.

These days, since the separation wall had gone up, most of the fatalities in the Jerusalem–Ramallah region were caused by car accidents. There were bad road injuries and deaths in Saar’s sector every week. But right away Saar could see that the Jaba crash was extreme, in the devastation of the site, the distress of the crowd, the horror of seeing those small backpacks on the road.

Saar arrived to the sight of soldiers and Palestinians in a shouting match. He didn’t know what the fight was about, but the Palestinians, who were plainclothes security officers, were not supposed to be there. This was in Area C, the part of the West Bank fully controlled by Israel.

The fight had started over the beating of Salem and then turned into a dispute over jurisdiction. The Palestinians wanted the Israeli soldiers to leave, an unheard-of request. As the two sides argued, the top brass pulled up—Ibrahim Salama, head of the Palestinian Interior Ministry in the Jerusalem area. Saar had heard of him though they had never met. Ibrahim was Abed’s first cousin, but he had no idea that Abed’s son had been on the bus, nor even that it had come from Anata.

It was a visit from Abu Mohammad Bahri, a grandfather of one of the children, that had alerted him to the accident. An enormous elderly man in a kaffiyeh, Abu Mohammad had been driving from Shuafat Camp to renew his ID at the Interior Ministry in a-Ram when he saw the collision, unaware that his granddaughter Tala Bahri was on the bus or that she was seriously injured. Abu Mohammad was distressed and speaking unintelligibly, but Ibrahim could make out that he had seen something terrible near the Jaba checkpoint.

Then Ibrahim’s staff started talking about it. Bringing his deputies and a security detail, Ibrahim decided to see for himself what was happening. He was one of the few PA officials Israel allowed to travel in the West Bank with armed bodyguards. He needed them: among the most visible faces of security cooperation with Israel, Ibrahim had made many Palestinian enemies. Even Abed believed his cousin’s work with Israelis crossed a red line. Ibrahim oversaw the recruitment of informants and arrest of militants and was always in meetings with powerful Israelis, from army generals to the defense minister, with whom he spoke in fluent Hebrew. He had been shot at more than once.

Ibrahim had the belly of a middle-aged man and the mischievous grin of a young boy. Cunning and proud of it, he liked to say he was a fox: he could bring someone out to sea and back without them realizing they were wet. He had recently married a second wife—the first one lived with his mother in Dahiyat a-Salaam, the new one with him in Ramallah, where he slept five days per week. Ibrahim liked to tell his Israeli army friends that when it came to his spouses he believed in Ariel Sharon’s Gaza withdrawal policy, known as “disengagement.” With the generals laughing, he’d add that he had tried and failed to bring his wives together in a truth and reconciliation commission.

Driving in two cars, Ibrahim and his entourage ran into the backup from the a-Ram roundabout, so they turned onto an unpaved path that ran parallel to the Jaba road. He had learned while in transit that the crash involved a Palestinian school bus and that parents were desperately trying to locate their children. When he reached an army roadblock, Ibrahim instructed his driver to stop the car, and he continued on foot. He was climbing down the rocky hill toward the crowd when he was waved over by an old friend, Yossi Stern, the head of Israel’s Civil Administration—a successor to the military government—in the Ramallah district. Yossi was in charge of giving Palestinians work and travel permits, approving settlement building, and demolishing Palestinian homes. He was also involved in coordinating security with the PA, which is how he knew Ibrahim.

Yossi was standing next to Saar, both of them in their green uniforms. Saar had on two backpacks, with an antenna rising above his shoulder. As Ibrahim made his way to join them, he could see the fight going on between the soldiers and the Palestinian officers. Clearly, de-escalation was the immediate goal. Right away, Ibrahim ordered the Palestinian officers at the center of the dispute to leave. Then he turned to Yossi. He knew the requests he was about to make were audacious, but the situation demanded nothing less. First, to give the PA security services control of the site, even though they weren’t allowed to be there. Second, to waive the need for permits for parents with green IDs and let them go through the checkpoints to Jerusalem.

It was Saar’s call, and he agreed, without even checking with his commander. It was the first and only time Saar saw the army relinquish control in Area C. Had the victims been Jews, it would have been out of the question—and Ibrahim would never have even asked. The army would help with whatever was needed, Saar told Ibrahim. He then withdrew his troops to the perimeter, handing authority to the plainclothes Palestinian officers and firefighters. Later they were joined by the PA police, who had been held up at the Beit El checkpoint, waiting for Israel’s permission to leave Ramallah.

ASHRAF QAYQAS, THE driver of the semitrailer, was brought to Hadassah Hospital at Mount Scopus. He was only lightly injured, and police investigators were able to question him at the hospital that same day. Ashraf used to live in Anata—across the street from Abed—and before becoming a truck driver, he had worked with a Bedouin friend of Abed’s repairing and reselling old Israeli cars.

That morning, Ashraf had left home at 6:00 A.M. for his job as a driver for a concrete factory in Atarot, a settlement industrial zone in East Jerusalem. By 6:30, he was in the empty semitrailer on the way to a limestone quarry near the Kokhav HaShahar settlement, twenty-nine miles away. He picked up a load of aggregate, delivered it to the Atarot factory, and then headed back out to the quarry for another load.

Kokhav HaShahar had been established as a military outpost in 1975, under a Labor government, on land seized by military order from the villages of Deir Jarir and Kufr Malik, and was turned into a civilian settlement five years later. The Kokhav HaShahar quarry was one of ten that were Israeli-owned in the West Bank. In 2010, settlement quarries transferred 94 percent of their natural stone product to Israel, accounting for a quarter of all mined materials consumed inside the state. The remaining 6 percent went to West Bank settlements, Palestinian construction, and the Civil Administration.

Just seven weeks before the accident, Israel’s High Court of Justice had ruled on the legality of the settler quarries in the West Bank. International law prohibits an occupying power from plundering the resources of the occupied. Pillage is a war crime. But the court ruled unanimously that the state was permitted to exploit the West Bank’s natural resources. The reason given by its president, Dorit Beinisch, who was considered a liberal justice in Israel, was that the occupation was so long-standing that it required the “adjustment of the law to the reality on the ground.”

In his room at Hadassah Mount Scopus, Ashraf told the police investigators that he didn’t know how the collision had happened. He couldn’t say why he had driven into oncoming traffic or what had caused him to go well above the speed limit in awful weather—he had been driving at nearly twice the permitted speed: ninety kilometers on a road with a fifty-kilometer-per-hour limit. The rain had been coming down so hard he could barely see a few dozen feet ahead of him; his windshield wipers were at the highest setting and still they didn’t clear his view. He had tried to slow down as he approached the Jaba checkpoint. He hadn’t seen the bus, he said, because he had been looking at the road to avoid the potholes, which could have damaged the truck.

In fact, Ashraf had been grossly negligent. During a terrible storm, he had driven a thirty-ton, eighteen-wheel killing machine on a wet, declining slope at great speed. He also had twenty-five earlier traffic offenses, had limited experience operating heavy vehicles—he’d obtained his license only the previous year—and had been working for the concrete company for just one month. The company had been negligent, too: it hadn’t trained Ashraf properly in the use of the very complex braking system on the truck, a ten-wheel top-of-the-line Mercedes-Benz Actros cabin connected to an advanced eight-wheel trailer.

Ashraf denied—but in subsequent testimony admitted—that when he had entered the a-Ram roundabout he might have applied a retarder, a braking device, and neglected to turn it off. The retarder, Ashraf explained, would automatically engage as soon as he lifted his foot off the gas to slow down. He failed to mention that the manual for the truck contained a bold warning in red not to use the retarder in wet conditions, where it could cause the drive wheels to lock and skid.

Later, another police investigator asked Ashraf one final question: “You’re a professional driver. In the rain can you drive with a retarder?”

“Yes,” Ashraf answered. “There’s no problem with it in the rain, but you have to be cautious with it.”

In their report, the police concluded that Ashraf’s speeding, lack of training, and inexperience with the truck’s deceleration system was what had caused the accident. A driver with experience, it stated, would know that you cannot apply a retarder on a wet road.

Ashraf had been on a long, straight stretch when he lost control. As the truck veered into the two lanes of oncoming traffic, the jackknifed trailer began careening across the entire width of the road, banging against the cabin. The truck kept moving toward the school bus, its trailer swinging wildly. Although the bus slowed down and pulled to a near stop on the sloped shoulder, it was in the path of the truck. The truck struck the front of the bus, shoving it backward, and then continued to spin around in a circle, its trailer fanning out behind it. A moment later the trailer slammed into the bus and flipped it over. The impact caused a short circuit in the bus’s fuse box, igniting a fire that was fanned by the day’s strong winds.

AT A HOSPITAL in central Israel, Radwan Tawam lay in bed, groggy from the painkillers. He had blocked out the collision, the fire on his legs, Salem and Huda pulling him through the broken front window, the twenty minutes on the ground until Nader Morrar arrived, and the agonizing ambulance ride to the Ramallah hospital. He had no memory of seeing his wife in tears by the elevators or of his brother telling the doctor there was no way he was going to amputate Radwan’s legs at that crappy place. He had no recollection of his brother using connections to get him transferred to Tel Hashomer Hospital near Tel Aviv or of his cousin, a dentist, riding with him as Radwan repeated, “It’s not my fault, it’s not my fault.”

What he remembered was waking, after a two-month coma, and finding that he had no legs. The shock triggered a stroke and a heart attack; the doctors induced a second, monthlong coma. When Radwan came around again, three months after the accident, he had lost the ability to talk. Learning that six children and one teacher had died, he broke down. After many months of rehabilitation, he was able to speak through one side of his mouth but with a slur. The hardest part was not the wheelchair itself but his humiliating, infantilizing dependency. At first he refused to wear diapers, trying and failing to go to the bathroom on his own. When the doctors took the cast off his arm, they saw that the hospital in Ramallah had set it incorrectly, leaving a large bump on his wrist. That he survived at all was due to his wife, Radwan was sure. She slept at the hospital for more than a year.

All kinds of swindlers came to Radwan, promising millions in compensation for the accident. He and his wife felt helpless dealing with Israeli lawyers and documents in a language they didn’t understand. One of his sons worked at the SodaStream factory in the settlement industrial zone of Mishor Adumim, next to Khan al-Ahmar. His son’s manager, who had a blue Jerusalem ID, spoke good Hebrew and offered to help. But after they gave him money to hire a lawyer, he ran off with it. Radwan heard he had moved to Beit Safafa, on the other side of the wall. With no way to go to Jerusalem to find him, Radwan gave up on getting the money back.

His working life was over, and so was his friendship with Sami, who disappeared after the accident. Radwan would spend the rest of his days confined to his home in Jaba, his wife wheeling him from room to room, the explosions from the limestone quarry sounding in the background as he watched the dust settle on the fig and olive trees in his front yard.