Chapter 5

Spaces real and imagined

Home is where the heart is. In contemporary American culture, the phrase has become ubiquitous. Framed on the walls of family rooms, cross-stitched on throw pillows, written in cursive script on coffee cups: the phrase attempts to capture the sense of attachment, belonging, and close connection that nuclear families feel towards their living spaces. Oddly enough, this same phrase could easily serve as a motto for many monastics who have left their natal homes and families to find alternative places of residence, whether in deserts or forests, whether alone or in a community.

In a blog dated 11 October 2011, Benedictine Sister Ann Marie Wainright reflected on a new postulant’s questions concerning the size and layout of nuns’ cells—questions that prompted memories of the day she moved into her own room in the convent years before. Composing her blog entry in that same cell with sunlight streaming through her window, she wrote, ‘If home is where the heart is, then I was at home—not just in my room, but in the heart of God.’

This same connection was made by early Christian monks. In the 4th century, one of the most prominent monastic centres in Egypt was a settlement called Scetis (Wādī al-Naṭrūn), located west of the Nile Delta. Scetis is the setting for many stories in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, including one anecdote about the monk Moses the Black. One day, Moses tells one of his brothers: ‘Go, sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.’ In this teaching, the cell is conspicuously presented as an extension of the monastic self. That is, for Moses and his compatriots, you are where you live. This insight is also reflected in the geographical nomenclature for Scetis itself. In the indigenous Coptic language, the region is known as the ‘Weigher of Hearts’ (Shiēt, from the roots, shi, ‘weigh, measure’, and hēt, ‘heart’). For the monks of Scetis, their desert cell was the place where their hearts were weighed in the balance by God.

With this close relationship between residential spaces and monastic identities in mind, I now turn to the locations where monks and nuns live in community: monasteries. First, I will focus on monastic archaeology. What can material evidence tell us about monks’ and nuns’ places and modes of habitation, from architecture to agriculture, from practices of visitation to visual culture? Second, I will also examine monastic stories and art to mine the meanings that such landscapes and homescapes had for their resident populations. What did the cell, the monastery, the desert, and the forest, signify for the monastic imaginary? How have local spaces imprinted themselves on monastic pieties, and vice versa?

The archaeology of monasteries

I begin with the material evidence for monastic places of habitation. Historically, monks and nuns have shown a remarkable ability to adapt their physical environments to suit their own needs. Such settlement patterns are attested in literary sources as well as the archaeological record.

In Buddhist and Christian Lives of eminent monks and nuns, ascetics frequently occupy remote caves to pursue a life of renunciation and meditation. In the Chinese biography of Bo Sengguang, for example, the 4th-century Jin monk withdraws to a cave on Mount Shicheng—later known as Hermit Peak—in the province of Shan. There he is haunted by ‘the spirit of the mountain’. In the Life of St Benedict, a ‘narrow cave … overhung by a high cliff’ in Subiaco, north-east of Rome, serves as the Italian monk’s initial retreat. There he is tempted by the devil.

Other stories describe how monks reclaimed and occupied previously existing architectural structures. In the Lives of Anthony and Pachomius, a deserted fortress and an abandoned village are respectively reclaimed for monastic practice. But of course, monastic communities also constructed structures from scratch, planning and building their architecture to specification. Thus, early stories about the Buddha describe financial negotiations for the donation of land used for the construction of new stupas and monastic retreats; and for early Buddhist communities, the Bhikkhu Pātimokkha establishes standards for ‘having a large dwelling place made’, including specifying acceptable locations, the proper amount of plaster, and the placement of doors and windows.

The archaeological evidence for monastic settlements attests to a correspondingly diverse range of architectural and residential practices. Here, it is helpful to think in terms of two different patterns for the physical construction of monastic spaces: first, adaptive reuse of the environment; and second, purpose-built architecture.

In their natural state, caves make for rather inhospitable settings for human habitation, and this is the reason stories about monastic heroes often highlight the threat of exposure and danger associated with such spaces as a constituent component of ascetic renunciation. But in practice, it seems likely that even the most hardened cave-dwelling hermits adapted their physical environments in basic ways to suit their needs. (If they hadn’t, there would be no tangible evidence to confirm they had ever been there!) Architecturally speaking, such adaptive reuse could take a form as simple as the building of a low enclosure wall for privacy, or the levelling of a ledge to be used as a bed. But it could also take more elaborate forms, as in the case of rock-cut monastic complexes from ancient India, Nepal, and China, to early medieval Egypt and Italy.

One of our earliest pieces of evidence for the modification of caves into monastic dwellings comes from 3rd- or 2nd-century bce Nepal, where a number of rock-hewn huts from the period have survived at a site named Gum Bahal, which translates as ‘The Monastery of Caves’. These huts are ‘small boxlike structures’ consisting of two chambers: an entrance vestibule and a sleeping area. Since even the task of excavating the rock mass to create small square chambers would have necessitated a significant investment of time and money, archaeologists think that such huts would have been occupied by high-ranking monastic teachers. A group of seven caves in Bihar, India, may date from even earlier, probably to the middle of the 3rd century bce. The most prominent of them is the Grotto of Lomas Rishi: carved and initially occupied by a sect of Jain monks (Ajivikas), it has a hut-like façade designed to look like timber.

Other surviving rock-cut vihāras in India and China show a more expansive and refined architectural plan. At the monastic sites of Pitalkhorā and Bhājā in Maharashtra, the rock has been carved to mimic ornate wooden architectural designs. Later vihāras from the same region show how caves were opened up into central arcaded courtyards, with ten to twenty cells arrayed around the outer borders, and decorated with sculptures and painted panels. One especially complex example (Ellora Cave 12) has three storeys, approximately thirty small chambers and/or shrines, and a pillared hall measuring around thirty-five square metres in area. At Ajaṇṭā in western India, thirty-six caves carved into a 250-foot-high rock face became home to monks around the turn of the Common Era: by the late 5th century (460–80 ce) an elaborate artistic programme had been executed on the cave walls, including colourful paintings of the lives of the Buddha and sculpted reliefs of nymphs, sea monsters, and genies. Around the same time in China, rock-cut monasteries became way stations for missionaries bringing Buddhist teachings to that region. One such station were the Mogao caves at Dunhuang, which feature ornate sculptures and paintings, including scenes of the Buddha’s incarnations.

One finds analogous adaptations of natural space in Christian cave monasteries as well. At an Egyptian site called Naqlun in the Fayoum Oasis, for example, excavators have discovered a total of eighty-nine rock-cut hermitages dating from the 5th to the 12th century and carved out of the porous tufa that forms the hills and ravines bordering the oasis. Designed for one or two occupants, the hermitages at Naqlun consist of multiple rooms, often plastered, in various sizes and shapes: these could include vestibules, inner and outer courtyards, windows, sleeping quarters, cooking areas, storage spaces, and prayer rooms. The lack of ovens for baking or facilities for storing wine and water suggests that the hermits living there had to depend on deliveries of foodstuffs from the walled monastic community situated nearby.

In Italy, the ‘Sacred Cave’ (Sacro Speco) at Subiaco legendarily associated with St Benedict’s early monastic life provides an interesting comparison. There are no solid archaeological data regarding its period of origin, but surviving evidence confirms that the cave was (re)inhabited by hermit monks in the late 11th century. By the turn of the 13th century a regular monastic community had been established there, and the cave church had become the subject of significant architectural and iconographic modification. From the medieval period to the present, the monks in residence have admitted pilgrims to the site, and visitors have been able to tour a multi-level monastic church carved out of the rock and decorated with an extensive wall-painting programme, including scenes from the life, death, and resurrection of Christ, and from the life and miracles of St Benedict. The lower level of the church features the ‘Sacred Cave’ itself, where Benedict was reputed to have begun his career as a monk. The walls of this holy grotto have been left as bare stone, which spatially conveys to visitors a sense of unmediated access to the monastery’s founding figure.

When it comes to their places of residence, monastics have not only adapted caves and other features of the natural landscape. They have also designed monasteries as purpose-built architecture. When made with less permanent materials like wood or mud brick, such structures have not often survived for archaeological study. But those that do survive give us a picture of diversified monastic forms and functions.

Purpose-built Buddhist monasteries may incorporate various architectural elements. As in the case of rock-cut cave sites, architecturally designed vihāras have typically been configured as ‘a series of cells enclosing three sides of a square courtyard’. But monastic complexes can, and often do, include other elements, including worship halls (chaityas), stupas, refectories, and connecting pathways.

In India, early examples show how these elements were often arranged in a north–south orientation, with flanking buildings to the east and west. The ancient monastic sites of Thotlakonda and Bavikonda in north coastal Andhra Pradesh, India, for example, are laid out along a similar axis. To the north is an area featuring a main stupa and worship hall. To the south lies a courtyard or cloister with a colonnaded hall at its centre, which is surrounded on three sides (east, west, and south) by residential cells. Further to the east is a refectory complex.

A similar ‘bilateral symmetry’ has also been observed at the Horyu-ji monastery (7th century ce) in Nara, Japan, where a ‘golden hall’ and a pagoda are placed on either side of a central axis leading towards a lecture hall to the north. In Japan such structures are characteristically raised on a stone platform (or an ascending series of platforms), and sometimes pagodas are located away from the central axis, outside exterior walls, or hidden among trees. At Horyu-ji, the monastic campus also integrates a range of other buildings, including a dormitory, dining hall, library, lecture hall, and bell tower.

The emphasis on architectural symmetry in the design of Buddhist monastic sites was conditioned, in part, by aesthetic factors, as well as the contours of local topography. In one notably idiosyncratic case, at the 11th-century Byōdō-in monastery outside Kyoto in Japan, one of the halls is designed ‘in the form of a phoenix with outstretched wings’ hovering over a reflecting pond within a beautifully manicured park. In his study of Buddhist monastic architecture in Sri Lanka, Senake Bandaranayake likewise describes an ‘organic’ layout in which built structures were integrated with and served as an extension of their natural environment. Later in this chapter, we will see how architectural landscapes became the subject of spatial imagination in monastic literature and art.

Purpose-built Christian monastic architecture also exhibits a diversity of forms, which may be divided into two main categories: the smaller-scale ‘cell’; and the larger-scale walled enclosure or ‘monastery’ proper. The former is analogous to domestic houses that serve as places of residence for individuals or small family units. As such, ‘cells’ typically incorporate rooms or spaces for sleeping, cooking, eating, receiving visitors, and private prayer. The latter is analogous to villages that accommodate communities of monks or nuns living and working together. As such, ‘monasteries’ often incorporate not only dormitories, kitchens, refectories, guesthouses, and churches, but also walls and gates, administrative and storage buildings, industrial and manufacturing facilities, wells with plumbing and irrigation systems, agricultural plots and orchards, streets and alleyways, and many other features common to small towns or large estates.

A paradigmatic example of the first category—the ‘cell’—is the early Christian monastic settlement of Kellia on the western outskirts of the Egyptian Delta. In Greek, the word Kellia in fact means ‘cells’, and the settlement took shape as a large cluster of small dwellings. In its heyday between the 4th and 8th centuries ce, the Kellia settlement covered more than forty-nine square miles and hosted upwards of 1,500 monastic cells. Most of the surviving remains date from the 6th or 7th centuries.

The dwellings at Kellia were primarily constructed from mud brick and ranged considerably in size. Small cells accommodating one to three people could measure between 180 and 600 square metres. These structures were equipped with sleeping quarters for an elder monk and perhaps one or two of his disciples, a storeroom, and areas designated for work and prayer. Sometimes they would also feature a reception area and an open courtyard, sometimes with a garden, well, and/or latrine. Medium-to-large cells accommodating anywhere from five to ten hermits could range from 700 to 2,700 square metres. These dwellings had open courtyards, larger halls for assembly, and more ornate decorations, including faux-sculptured columns and painted wall murals.

An analogous settlement pattern may be observed in Wādī al-Naṭrūn (ancient Scetis). Since 2006, the Yale Monastic Archaeology Project (YMAP) has conducted surveys and excavations at the Monastery of John the Little, where the remains of around eighty mud-brick residences dot the landscape outside a central walled enclosure with a main church. The site shows how two types of monastic organization—independent cells and a communal monastery—could coexist in practice. The work of the Yale team has concentrated in particular on one monastic cell measuring twenty-five by twenty-five metres (Residence B) and dating to the 9th and 10th centuries ce. The structure contains twenty-five rooms, including primary and secondary kitchen spaces, organized around a central courtyard. Among its rooms is one with prayer niches, an extensive wall-painting programme featuring equestrian martyrs and monastic saints, and several painted inscriptions.

For an example of the second category—the communal, walled ‘monastery’—we may turn to YMAP’s work at the White Monastery in Upper Egypt. In late antiquity, the White Monastery was part of the federation of three monasteries headed in the first half of the 5th century ce by Shenoute of Atripe, whose rules we studied in Chapter 3. The White and Red Monasteries were communities of male monks, while a convent in the village of Atripe to the south was home to female nuns. Since 2008, Yale has conducted surveys and excavations at the White Monastery, and in 2016 we initiated work on the remains of the women’s community at Atripe.

Located at the foot of the cliff at the western edge of the Nile Valley, the White Monastery resembled a village in physical layout and social organization. The monastery was bordered by an enclosure wall and accessed through a gate monitored by a doorkeeper. Inside the gate, the monumental 5th-century Church of St Shenoute, which still stands today, served as the central place of assembly and worship, and probably housed the monastic library (see Figure 5). Another chapel within the complex may have been designed as Shenoute’s burial place and shrine.

5. The monumental, 5th-century Church of St Shenoute at the White Monastery (Sohag, Egypt), viewed from the east.

To the south, west, and north-west of the main church, archaeological remains provide evidence for facilities that would have allowed the monastery to be virtually self-sufficient. These facilities included industrial installations for the processing of olive oil and dyes, kitchens with millstones for grinding grain and eleven or twelve bread-baking ovens, refectories for meal gatherings, dormitories for sleeping, a treasury building that combined administration and storage functions, and a huge well with an elaborate water distribution network. During Shenoute’s time, the monastery also maintained agricultural plots, orchards, and animal pens. Such a complex and extensive system of buildings and landholdings would have required constant administrative upkeep and a cadre of specialists (monastic or otherwise): industrial workers, bakers, cooks, servers, administrators, plumbers, farmers, tenders of livestock, and of course architects, civil engineers, and builders.

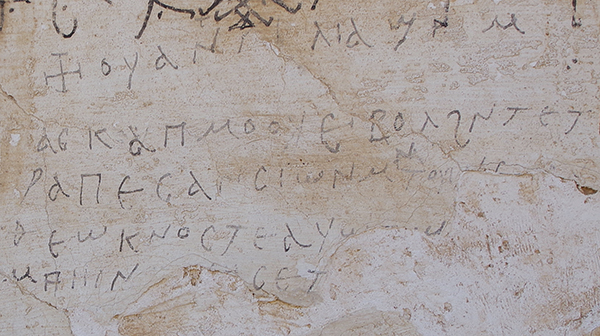

The women’s monastery at Atripe, located about five kilometres to the south of the White Monastery, shows how such communities could accommodate hybridized forms of architecture, with both adaptive reuse and purpose-built structures in evidence. Thus, the church at Atripe was built into the previously existing Ptolemaic temple in the town, but other monastic buildings—including a six-pillared hall and a large refectory with multiple circular eating spaces—were built outside the temple walls. Painted inscriptions (dipinti) analysed in 2016 and 2017 confirm that these spaces were used by female monastics, and that matters of food distribution remained a central concern. In one case, a young novice named Evangelia wrote a note on the wall of the refectory documenting her role in sending water and food out to members of the community (see Figure 6):

6. Late ancient Coptic dipinto (painted wall writing) by a young nun or female monastic apprentice named Evangelia on the wall of the refectory in the Shenoutean women’s monastery at Atripe (near Sohag, Egypt).

Medieval Christian monasteries in Europe developed their own distinctive architectural patterns to meet a similar range of everyday needs. Plans were typically organized around a central ‘cloister’ (from the Latin claustrum, ‘enclosure’). In early medieval Europe, as illustrated by the Plan of St Gall (820 ce), the cloister took the shape of a square colonnaded arcade or covered portico, bordered on one side by the monastic church and enclosed on the other sides by two-storey buildings containing a variety of facilities: dormitories, warming and cooling rooms, refectories, vestiaries, cellars, and larders. Smaller buildings at the corners could house lavatories, bathhouses, kitchens, bakeries, and breweries. Other variations included chapter houses (i.e. meeting rooms). The fundamental purpose of the cloister was to segregate the monks or nuns from the outside world.

Of course, different monastic orders adapted this monastic plan to their own purposes in different ways, and these adaptations had implications for the physical layout, land use, and labour. At the Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910, an increasing emphasis on liturgical service led to architectural renovations that amplified and accentuated the maior ecclesia (the ‘Great Church’). Beginning in the 12th century, the Cistercian reform movement shifted the emphasis, simplifying the liturgy and assigning manual labour to all members of the community, which included both monks and lay brothers. As a result, the monastery plan had to incorporate separate quarters outside the cloister for the lay brothers.

Cistercian monasteries such as Cîteaux and Clairvaux were often established in secluded, undeveloped settings, where the members of the community had to reclaim the land by clearing forests and planting fields. Once a monastery was established, it was the lay brothers—working in the buildings, fields, and water systems outside the cloister as masons, millers, fullers, weavers, bakers, tanners, smiths, farmers, shepherds, plumbers, and civil engineers—‘who enabled the early Cistercian communities to be self-supporting’. In this way, Cistercian monastic foundations could become economic and social centres.

Such was the case at Hailes Abbey in Gloucestershire, England, founded by the Earl of Cornwall in the 13th century. Its extensive landholdings included orchards and fish ponds, and its huge (104-metre-long) church hosted a vibrant pilgrimage industry centred around a contact relic, a phial of Christ’s blood kept in a shrine behind the holy altar.

Thus far, I have discussed the material realities of monastic archaeology and architecture, the physical spaces inhabited by monks and nuns. Such spaces imposed constraints upon movement and daily practice, but they could also be adapted through architectural renovations designed to address new needs in the community. An important part of monastic practice is the challenge of negotiating such spatial constraints, of defining (and redefining) the relationship between oneself and one’s physical environment. And yet, the spatial dimensions to this process of monastic identity formation cannot simply be reduced to the empirical distance between the walls of buildings. Monastics have also had an active hand in reimagining and mythologizing their physical environments, and this is the subject that will occupy our attention for the rest of this chapter.

Imagining monastic spaces and landscapes

If cells are extensions of the monastic self, they have also been understood as places that mediate contact and union with the divine. As Anthony was credited with saying: ‘Just as fish die if they stay too long out of water, so the monks who loiter outside their cells or pass their time with men of the world lose the intensity of inner peace.’ For their inhabitants, cells and monastic enclosures prove to be more than the sum of their material parts: they carry symbolic and spiritual value, reinforced through ritual practice. The architecture of monasteries is informed not only by site plan but also by embodied theologies.

In the case of Christian monasteries, such spiritual or theological value can be seen in the way that cruciform spaces shape the contours of worship and everyday life. One interesting example is the Monastery of St Simeon in north-west Syria. As mentioned in Chapter 2, Simeon (390–459 ce) was a holy hermit whose ascetic regime involved living on top of a 21-metre-tall pillar. Hundreds of pilgrims came from near and far to see the spectacle, to catch a glimpse, and to seek the blessings of the holy man. To accommodate the flow of visitors, a monastery with a hostel grew up around his column. The monastic church was laid out in the form of a cross with Simeon’s pillar at the midpoint. For pilgrims after his death, the architecture communicated that Simeon’s monastery fulfilled the promise of Christ’s crucifixion, simultaneously marking the centre of the world and pointing the way to heaven.

One also observes a symbolic negotiation of the horizontal and vertical in the medieval monastic churches built by the Knights Templar, a military order of warrior monks established in the 12th century who played an instrumental role in Crusader campaigns to the Holy Land. The order’s circular or polygonal churches were modelled after the temple and Christ’s tomb in Jerusalem. Prominent examples include the Holy Sepulchre in Cambridge (c.1130), the Temple Church in London (1185), the Templar Chapel in Laon, France (c.1180), and the Convent of Christ in Tomar, Portugal (late 12th century). Worshippers in these spaces understood themselves to be vicariously present as witnesses to the events of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection in the Holy Land, even as the high arches of the sanctuary space drew their focus upward to God.

Buddhist monasticism has trafficked in similar symbolic constructions of sacred spaces, where architectural structures mediate local and universal access to the holy. The establishment of monasteries at the sites associated with eight major events in the Buddha’s life mapped out an itinerary of loca sancta for pilgrims in northern India, linking those monastic foundations to their founding figure. The cyclical nature of such connections was reinforced and ‘summarized in eight set scenes (baxiang)’ commonly represented in hagiographical literature and art. One such iconographical example is a pigmented stone sculpture from Bodhgaya—now housed at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York—depicting the Buddha under the bodhi tree at his moment of enlightenment, with the other seven scenes depicted in miniature around him. Sometimes sculptures carved into the fabric of the walls themselves also prompted viewers to imagine monasteries as divine palaces and paradises, as in the case of the rock-cut Cave 16 at Ajaṇṭā in India, modelled after the heavenly abode of the god Indra.

The layout of Buddhist monasteries also sometimes provides universalizing coordinates for practitioners within the space. Perhaps the most paradigmatic example is the monastic use of the maṇḍala as a model for architecture and ritual practice.

Maṇḍalas are diagrams—carved into stone, or carefully plotted out in sand—that under some circumstances provide tantric practitioners with a means to visualize and attain enlightenment. Originally altars that were set into the floor as seats for the deities and their images, maṇḍalas came to be ‘envisioned as elaborate, bejeweled three-dimensional palaces atop Mount Meru, the imagined center of the Buddhist world system’. They are typically constructed in layers and concentric rings, with the centre and its four prongs representing the five victorious Buddhas, or jinas.

While the use of maṇḍalas is not restricted to monastic practice, Buddhist monks have long incorporated them into their architecture and ritual life. Two rock-cut cave monasteries (Caves 6 and 7) at Aurangabad in Maharashtra (north-western India) were designed in the form of esoteric maṇḍalas. Elsewhere in the same region, in Cave 12 at Ellora, an early eight-bodhisattva maṇḍala has been carved into the stone. Monks living and meditating at these sites thus would have understood the monastery itself to be ‘a cave in the side of Mount Meru, reaching the very core of the world-system axis’. Lindsay Jones has described this as the ‘architecturalization’ of the maṇḍala: at such sites the very act of moving through the temple or monastic space is implicitly framed as a figurative and psychological journey through both the universe and one’s own consciousness. In Tibetan monasteries, monks and nuns contemplate two-dimensional maṇḍala wall hangings and paintings and painstakingly create multicoloured maṇḍala diagrams out of sand (see Figure 7), while invoking deities and presenting offerings (food, flowers, incense, fire, water, etc.). These are acts that ritually mark the interior of the monastery as a rarefied space for attaining a purified state of wisdom and compassion leading to full enlightenment.

7. Tibetan nuns from the Keydong Thuk-Che-Che-Ling Nunnery (Kathmandu, Nepal) create a sand maṇḍala at Davis Museum, Wellesley College (23 February 2005).

In the artistic and literary imagination of monks and nuns, the landscape outside the monastery enclosure also comes to be viewed as sacralized territory, as an extension of the divine union realized within. The forest or desert surroundings are thus transformed—from a foreboding reminder of the world and its threats, to a verdant spiritual paradise.

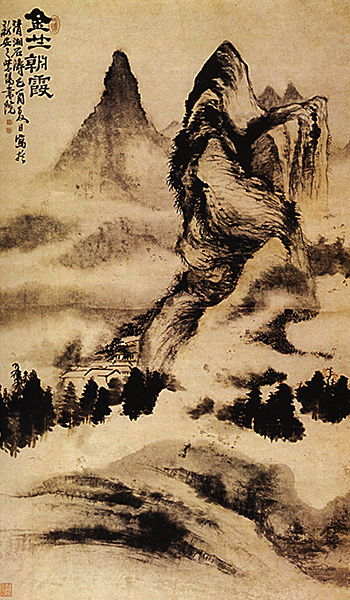

Medieval Chinese Buddhist artists frequently depict monasteries in idyllic mountain settings, nestled among trees by clear-flowing streams. One example is a painting by the 17th-century artist, Shitao. Entitled Light of Dawn on the Monastery, the artist uses an ink-on-wash technique to depict a scene in which the monastic buildings are nestled among pine trees and dwarfed by soaring mountain peaks with craggy summits stretching up into the heavens (see Figure 8).

8. Painting depicting a Chinese Buddhist monastery in an idyllic mountain landscape.

A written account of the Dajue Monastery in Luoyang, China, could just as easily describe the unidentified monastery represented in the painting: ‘The grounds were auspicious, sacred, and truly scenic … [and the monastery] backs on the mountain.’ Indeed, Chinese inscriptions and historical records often attend closely to the significance of topographical and natural features in and around the monastic foundation. Thus, a stone stele highlights how the intersection of rivers, marshes, and mountains mark the ‘sacred confines’ and ‘blessed ground’ at the Shaolin Monastery. Similarly, a Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang notes the presence of aromatic plants, evergreens, hollies, water lilies, and mallows at the Yaoguang Nunnery. In an entry on the Yongning si Monastery, the same source describes how the cypress, juniper, and pine caress the building, and celebrates the fact that ‘the beauty of the cloisters’ exceeds the heavenly ‘Palace of Purity’. Elsewhere, it dwells on the sweet and fragrant fruits, including pomegranates and grapes, that flourish at monastic sites.

James Robson has used the term ‘geopiety’ to describe such accounts. They capture the Chinese notion of fengsu (Japanese, fengshui), which places value on the intersection of the natural environment (feng) and human actions (su) performed within that environment. In this context, for monks or nuns seeking an auspicious place for monastic contemplation, location mattered. Landscape and practice mirror one another: the macro-cosmic paradise without reflects the micro-cosmic paradise within.

The monastic landscape as paradise is a theme found in Christian literature as well. Perhaps the best example of this is the Coptic Life of Onnophrius. It tells the story of a monk named Paphnutius who journeys into the far reaches of the desert trying to find the fabled hermit, Onnophrius, who wanders the wilderness naked and lives in a small hut under a date palm, subsisting on a diet of plants. When he finds him, Onnophrius tells his visitor how the Lord provided him with ‘twelve bunches of dates’ each year and ‘made the other plants that grow in the desert places sweet in my mouth, sweeter than honey in my mouth’. After receiving instructions, Paphnutius is sent back to his own community at Scetis to share his teachings with the brothers there. On his way home, he runs across a well of water surrounded by an oasis of trees, including ‘date palms … laden with fruit’ and ‘citron and pomegranate and fig trees and apple trees and grapes and nectarine trees’, as well as ‘some myrtle trees … and other trees that gave off a sweet fragrance’. Walking among them, Paphnutius asks himself ‘Is this God’s paradise?’ (Life 28–9). Thus, as Tim Vivian has argued, the Life effectively presents the desert as a ‘paradise regained’ by anchorites like Onnophrius, who have returned to the original innocence of Adam and whose heroic piety has made the barren wasteland fertile again like the Garden of Eden.

This vision of monastic sites as Edenic persisted through the medieval period and into modern times. The 12th-century Latin authors Honorius Augustodunensis and Hugh of Fouilloy envisioned monasteries as earthly paradises, likening ‘the body of the Lord’ celebrated in the Mass, and the evergreen planted in the cloister lawn, to the Tree of Life. Their contemporary, the Benedictine abbess and mystic, Hildegard of Bingen, wrote that monastic virgins—in both their buildings and their bodies—remained ‘in the unsullied purity of paradise’. Hildegard famously composed liturgical hymns for her German convent that were meant to ‘recall to mind that divine melody of praise which Adam, in company with the angels, enjoyed in God before his fall’.

In the Christian East, for centuries, the sayings of the early desert mothers and fathers have been transmitted under titles such as The Paradise of the Fathers and The Garden of the Monks. These collections continue to be used as training manuals in monasteries and convents today. Finally, in contemporary North America, Catholic publishers now print devotional volumes like David Keller’s Oasis of Wisdom (2005), where the early monastic heroes of the faith are presented as an Edenic wellspring of renewal for a church parched by modern secularism. In such publications, the places and practices of early Christian monks and nuns are reclaimed for 21st-century pieties of prayer and devotion, and it is to such modern monastic forms of expression that I now turn.