Chapter 1

The Conquest of Eden

Possession and Dominion in Early Virginia

After good deliberation, hee [Wahunsonacock] began to describe mee the Countreys beyond the Falles, with many of the rest…Nations upon the toppe of the heade of the Bay…the Southerly Countries also…[and] a countrie called Anone, where they have an abundance of Brasse, and houses walled as ours. I requited his discourse, seeing what pride hee had in his great and spacious Dominions, seeing that all hee knew were under his Territories.

—John Smith

The land which we have searched out is a very good land, [and] if the Lord love us, he will bring our people to it, and will give it us for a possession.

—Robert Johnson

By the early 1580s, few promoters of colonization—whether statesmen, merchants, or scholars—seriously doubted England's right to take possession of those parts of the Americas uninhabited by Christians. Sir George Peckham invoked the “Law of Nations,” which sanctioned trade between Christians and “Infidels or Savages,” the “Law of Armes” which allowed the taking of foreign lands by force, and the Law of God, which enjoined Christian rulers to settle those lands “for the establishment of God's worde” to justify English claims. In ancient times and “since the nativitie of Christ,” he pointed out, “mightie and puissant Emperours and Kings have performed the like, I say to plant, possesse, and subdue.” Spain's exclusive claims to the New World—by virtue of first discovery and papal donation—were explicitly rejected. Elizabeth I did not understand why she or any “Princes subjects should be debarred from the Indies, which she could not perswade herself the Spaniard had any just Title to by the Bishop of Rome's Donation.” With laudable pragmatism if shaky geography, Richard Grenville advocated the establishment of English colonies in South America on the grounds that “since the Portugall hath attained one parte of the newe founde worlde to the Este, the Spaniarde an other to the weste, the Frenche the thirde to the northe: nowe the fourthe to the southe is by gods providence lefte for Englande.”1

The voyages of Martin Frobisher to Terra Incognita in search of a northwest passage and gold between 1576 and 1578 and Sir Humphrey Gilbert's ill-fated attempt to establish plantations in Newfoundland and along the northern seaboard conjured up what seemed to be a very real possibility of the English becoming the dominant power in the North Atlantic. John Dee, the Hermetic magus who influenced a generation of mariners and explorers, believed an Imperium britannicum was imminent. Claiming America for the English on the grounds of discovery and conquest by the Welsh prince, Owen Madoc, the legendary King Arthur centuries before, and voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot in the reign of Henry VII, he set out the queen's right to take possession of “foreyn Regions”: By the “same Order that other Christian Princes do now adayes make Conquests uppon the heathen people, we allso have to procede herein: both to Recover the Premisses, and likewise by Conquest to enlarge the Bownds of the foresayd Title Royall.” Richard Hakluyt the younger, the greatest propagandist of his age, was perplexed that “since the first discoverie of America (which is nowe full fourscore and tenne yeeres), after so great conquests and plantings by the Spaniardes and Portingales there, that wee of Englande could never have the grace to set fast footing in such fertill and temperate places as are left us yet unpossessed of them.” Founding colonies would be a clear signal of England's intent to stake a claim to American lands and seas as other European powers had done, and not to be shut out of the New World by the Spanish or anyone else. The crown's dominions would be enlarged, the treasury's coffers filled, and national honor satisfied. The “plantinge of twoo or three strong fortes upon some goodd havens” on the mainland between Florida and Cape Breton would provide convenient bases for fleets of privateers operating in American waters, eventually weakening Spanish power in the Old World as well as the New. Finally, as the most forward-looking writers such as Christopher Carleill, Peckham, and the two Richard Hakluyts pointed out, colonies would promote valuable commerce and long-term prosperity, as well as social and economic well being at home.2

But while the English had little doubt about the justice of their rights to establish colonies or the long-term benefits they would bring, there was less certainty about how those rights would be realized and how English settlers would be received by native populations. If first discovery was vital to claims of possession so too was the fact of occupation. It is unlikely Spain and Portugal would have been able to hold onto their colonies for long without settling and developing them, and it was precisely those regions of the Americas largely uninhabited by the Spanish that other colonizing powers eventually seized upon. Rituals of possession—the unfurling of flags, solemn declarations, the erection of crosses and monuments—pronounced formal title to the land, but ultimately occupation and the capacity to defend settlements from internal and external aggressors proved to be the crucial test for all colonizers.3 In this sense, the founding of England's first permanent colony in America, Virginia, and the protracted struggle between the English and indigenous peoples that ensued, is of particular interest. English justifications for conquest and possession were not simply worked out in abstract but were significantly influenced by the experience of contact, notably by the hostilities that stigmatized Anglo-Indian relations at Roanoke and Jamestown.4

England's First Virginia

English settlement of Virginia began not on the James River but a hundred miles to the south at Roanoke Island, on the Outer Banks of modern North Carolina. Following the death of Sir Humphrey Gilbert on the high seas in September 1583 returning from Newfoundland, the mantle of chief sponsor of England's colonizing efforts fell on the broad shoulders of the queen's new favorite, Walter Ralegh. Letters patent issued by Elizabeth in the spring of 1584 empowered him to “discover search fynde out and viewe such remote heathen and barbarous landes Contries and territories not actually possessed of any Christian Prynce and inhabited by Christian people” and to “holde occupy and enioye…forever all the soyle of all such landes Countreys and territories so to be discovered or possessed.” The wording was conventional, derived from the patent granted by Henry VII to John Cabot before the voyage of 1497, which in turn was based on papal injunctions, such as the bull Inter Caetera issued by Alexander VI in 1493, the principal legal justification for Spanish claims to the New World. As we have seen, the English did not subscribe to the exclusionary intent of the Alexandrine bulls, but they adopted without question the centuries-old dictum that newly discovered “savage” or “heathen” lands could be legitimately possessed and settled by Christians.5

The decision to plant a colony at Roanoke was probably determined by Dee's understanding of the geography of the American coast, as illustrated by his map of 1580, and Simon Fernandes, the Portuguese master mariner in Ralegh's service who had explored the region some years earlier with the Spanish. Even so, much of the mid-Atlantic seaboard remained a mystery. While writers and propagandists had built up a growing body of knowledge about America in general during the previous three decades, and sporadic privateering expeditions had added more detailed information about the Caribbean and Spanish Main, relatively little was known about the mainland north of Spanish settlements. Ralegh could have had only a very rough idea about the extent or potential of the lands he now formally possessed, and consequently his first decision was to dispatch two small vessels under Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, guided by Fernandes, to reconnoiter the region and find a location suitable for settlement.

Arriving off the Outer Banks in early July 1584, after a week or so sailing along the coast, Fernandes eventually discovered an entrance into the inner “Sea” where Amadas and Barlowe formally took possession of the region “in the right of the Queenes most excellent Maiestie” and their master, Ralegh. Barlowe's account, carefully edited for publicity purposes, revealed a land ripe for occupation. On the island of Hatarask, there were “many goodly woods, full of Deere, Conies, Hares, and Fowle, even in the midst of Summer.” The forests were not like those of Muscovy and Bohemia, “barren and fruitlesse,” but contained “the highest and reddest Cedars of the world” as well as “many other [trees] of excellent smell, and qualitie.” After a few days on the island they encountered a group of local Indians, described as a “very handsome, and goodly people, and in their behaviour as mannerly, and civill, as any of Europe.” The king of the local tribe (Secotans) was called Wingina and, Barlowe observed, was “greatly obeyed, and his brothers, and children reveranced.”6 Here was Eden, a land of plenty where the “earth bringeth foorth all things in abondance, as in the first creation, without toile or labour.” In a phrase reminiscent of Peter Martyr, the great Milanese scholar who had written an influential account of America half a century before, the Indians were described as a “very handsome, and goodly people,…most gentle, loving, and faithfull, void of all guile, and treason,…such as lived after the manner of the golden age.” Besides emphasizing the Indians' simple way of life, Barlowe was careful to detail their weaponry and methods of warfare, themes developed in Thomas Hariot's more elaborate description published a few years later. He, like Barlowe, believed the Indians “in respect of troubling our inhabiting and planting,” posed little threat, and was hopeful that “through discreet dealing and governement” would be brought to “the trueth, and consequently to honour, obey, feare and love us.”7

Effective as it may have been as a piece of propaganda, Barlowe's account was highly misleading in providing a realistic assessment of the difficulties of establishing a settlement in the Outer Banks. The shallow waters of the sounds and treacherous waters offshore were wholly unsuitable for oceangoing vessels, which were forced to anchor a couple of miles off the coast exposed to the fury of Atlantic storms. As a potential harbor for privateering fleets a worse location could hardly be imagined. His depiction of the natural bounty of the region, a land of milk and honey where little effort was needed to subsist, was merely a conventional reworking of the age-old fantasy of Arcadia, which had little to do with the practicalities of provisioning a colony and creating self-sufficiency in foodstuffs. Finally, his view of simple and pliant Indians who would not only assist English colonists in establishing themselves but, in time, would provide a docile labor force, ignored evidence all around him of warlike and independent peoples who would fight tenaciously to defend their lands. Successful in raising interest and financial backing in England, Barlowe's account left the first colonists dangerously unprepared for the conditions they would encounter and ultimately contributed to the disasters that followed.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that within six months of the arrival of a colonizing expedition under the command of Ralph Lane the following year relations with local tribes had broken down, mainly as a result of English aggression. The Secotans, Lane reported, were convinced the settlers were “fully bent to destroy them…[and] they had the like meaning towards us.” Hariot was told of a prophecy “that there were more of our generation [English] yet to come, to kill theirs and take their places.” The collapse of the Roanoke colony and the hostilities that scarred Anglo-Indian relations left an enduring legacy. Menatonon, chief of the Chowanocs, informed Lane of a powerful king who lived in the north on a great bay, who “had trafficke with white men” but who was “loth to suffer any strangers to enter into his Countrey.”8 This was Wahunsonacock, paramount chief of the Powhatans, at that moment consolidating his territories to the north in Virginia, and it is more than likely news of the violent and unpredictable behavior of the English had come to his ears. For their part, the English remained convinced of the potential bounty of “the maine of Virginea” and of the imperative to possess it. Richard Hakluyt believed the conquest of Virginia could be accomplished with far less difficulty than the subjugation of the “warrelike” Irish. A well-armed force would be quite capable of overcoming “such stubborne Savages as shall refuse obedience to her Majestie.” Events at Roanoke revealed that the Indians were far removed from the innocent and peace-loving peoples characterized by Barlowe. To English eyes, the treachery and hostility of local tribes, (“betrayed by our owne Savages,” said Lane) together with their obstinate resistance to civilized ways, rendered them a more intractable presence than had been anticipated.9 It was a lesson taken seriously by the Jamestown colonists twenty years later.

“Fatall Possession”: The Founding of Jamestown

By the time the English attempted once again to establish permanent settlements in America, the entire complexion of European colonization had changed. During the 1580s and 1590s, scores of English privateers had set out to plunder Spanish treasure fleets on the high seas or mount daring assaults on Spain's rich possessions in the West Indies and along the Main. Most were modest ventures made up of one or two ships in consort but some, such as Drake's voyages of 1585 and 1595, were full-scale military expeditions involving large fleets and several thousand men. Never before had English shipping been so common in American waters, and as a result increasing numbers of mariners and merchants acquired invaluable knowledge of transatlantic crossings, Caribbean islands, and the American coast. At the same time efforts to plant colonies continued, encouraged in part by the seemingly tenuous hold of the Spanish over much of their American empire and by the persistent vision of finding gold and other precious minerals or at the very least establishing a trade in the valuable natural commodities of the region. Ralegh's exploration of the Orinoco to the “rich and beawtifull Empire of Guiana” in search of the golden city of El Dorado was believed practical because that part of the Main was virtually uninhabited by Spanish settlers or “any Christian man, but onely the Caribes, Indians, and salvages.” He played for high stakes and dreamt of English colonies in Guiana comparable in wealth to Mexico and Peru, of an English New World (a New Britannia) that would eventually rival Spain's in riches and power, but justly governed by a virtuous English monarch avoiding the cruelty and tyranny of the Spanish conquista. Even when tales of the fabulous Indian civilization of Manoa proved worthless, the English continued exploring the area from the Orinoco to the Amazon (known as the Wild Coast), owing to the emergence of the area as a major producer of tobacco, which by the 1590s and early 1600s was becoming increasingly popular in Europe and commanded high prices.10

The Wild Coast marked the southernmost limit of English voyages in this period, but at the same time West Country and London merchants, backed by influential statesmen such as Lord Burghley, the Lord Treasurer, were renewing their interests in the far north, initially the Gulf of St. Lawrence and its valuable fisheries where the French and Basques were establishing themselves, and subsequently along the coast of Maine and New England. In the late 1590s, the failure of an unlikely scheme to plant a colony of Puritan dissenters in the Magdalen Islands on “Ramea” (Amherst Island) in the Gulf persuaded English investors to look further south where they would avoid direct competition with the French. Voyages between 1602 and 1605, involving explorations of Penobscot Bay and nearby islands, Cape Cod, and the coastline as far as Narragansett Bay, were followed by enthusiastic descriptions of the natural fertility of the land, waters teeming with fish (in greater plenty than was found off Newfoundland), and the friendliness of local Indians.11 But perhaps more important than individual discoveries themselves was the broader implication of the voyages. By the opening years of the seventeenth century it was becoming clear that if Spanish warships remained a threat along much of the coast from Florida to South Carolina, and the French were tightening their grip on the St. Lawrence, then to have any real chance of success English colonizing projects would necessarily have to be located somewhere along the nine hundred miles from Cape Fear to Nova Scotia. New England represented one possibility; the other was the Chesapeake.

The succession of James I to the throne in 1603 marked an important change in foreign policy. Having little desire to continue the war against Spain, he quickly negotiated a peace treaty ending the plunder of Spanish shipping and possessions. But although condemning piracy in the Atlantic and Caribbean, James had no intention of renouncing English claims to the American mainland north of Florida and lent his tacit support to a number of schemes to establish colonies along the northeastern seaboard. West Country merchants were anxious to exploit the fish, oil, furs, and timber of New England, while their London counterparts, with connections in the Mediterranean and Levant, were keen to promote colonies that would produce commodities traditionally imported from southern Europe—citrus fruits, wine, olives, raisins, sugar, dyestuffs, salt, and rice—as well as the kinds of industrial crops that were being intensively cultivated on marginal lands around London and elsewhere in southern and central England. By the royal charter of April 10, 1606, the North American coast was divided into two spheres of interest: the Plymouth group (which also represented merchants and financiers from Bristol, Exeter, and smaller outports) was permitted to settle lands in latitudes between 38 and 45 degrees, namely New England, while the London group was allowed to establish colonies in the south between 34 and 41 degrees, from North Carolina to the Chesapeake.12

Leaving shortly before Christmas 1606, the expedition financed by the London Company set out for the Chesapeake Bay under the command of the experienced mariner Christopher Newport. After a leisurely crossing, the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery, carrying about 144 adventurers and crew, rounded the Virginia capes and entered the Chesapeake Bay in late April 1607. Most of the first “settlers” in fact went not to settle but to establish a beachhead, explore the land, search for a river passage to the South Sea, and with luck find gold or silver mines (“To get the pearl and gold”). The majority signed on with the hope of returning home within a year or two, preferably rich. Although the men were instructed to sow wheat and other crops “for Victual” to promote self-sufficiency, the colony was not planned as an agricultural community, and no women or children were taken along to create the conditions for family life. That would come later once the colony was secured, but in the meantime the primary task of the first expedition was to rediscover the Chesapeake, take possession for the English, and survey its resources.13

The colonists were impressed by their first view of the land. George Percy wrote with unrestrained delight of the “faire meddowes and goodly tall Trees, with such Fresh-waters running through the woods, as I was almost ravished at the sight thereof.” To give thanks for their safe arrival and to mark the country as now belonging to the English, Newport's men named Cape Henry in honor of the king's eldest son and erected a cross there. First contacts with the Indians were mixed. A small landing party sent to scout the area around the cape was attacked by “Savages creeping upon all foure, from the Hills like Beares, with their Bowes in their mouthes,” who according to George Percy, “charged us very desperately” and wounded a couple of men before retiring into the woods “with a great noise.” A few days later, however, the colonists were entertained by the Indians of Kecoughtan and were welcomed also by the Paspaheghs and “Rapahannas” (Quiyoughcohannocks). The English soon learned that different tribes had very different responses towards them.14

During the next two weeks the settlers explored the lower reaches of the James River, searching for a suitable site to establish themselves. George Percy favored a point of land (named by the English “Archers Hope”) on the creek where forty years earlier Spanish Jesuits had landed before crossing to the York River, but the eventual site chosen was further upriver on Jamestown Island, “in Paspihas Countrey,” about sixty miles from the coast. Newport was anxious to begin exploring the region and a week after their arrival left the newly established colony with twenty-three men on a voyage of discovery up the James River, determined not to return before finding the “head of this Ryver, the Laake mentyoned by others heretofore, the Sea againe, the Mountaynes Apalatsi, or some issue.”15 The expedition represented a belated continuation of the reconnaissance of the bay begun by John White and Thomas Hariot, who had set out from Roanoke in the winter of 1585. White and Hariot had scouted the lands of the lower reaches of the James along its southern shore to the Nansemond, and Newport now intended to carry the exploration of the James to its conclusion in the interior. All along the river the Englishmen were met by friendly tribes apparently eager to trade and Newport learned much from them, notably the existence of a great king, Powhatan (Wahunsonacock), and lands to the west where Powhatan's enemies, the Monacans, lived in the mountains of “Quirank.” The falls, “by reason of the Rockes and Isles,” however, rendered any further progress up the river impossible and effectively put an end to the hope of quick and easy access to the lands beyond.

Nevertheless, from Newport's point of view the voyage had been a success, despite the disappointment of failing to find a passage to the western sea. The English now had a good idea of the extent of the river and had learned something about the peoples who lived along it. The river ran by estimation 160 miles “into the mayne land between two fertile and fragrant bankes,” was between a quarter and two miles wide, and could be navigated by ocean-going shipping most of its length up to the falls. On either side, the country abounded with fair trees, wild fruits, and game, and according to Gabriel Archer, the river teemed with “multitudes of fish, bankes of oysters, and many great crabbs better in tast than ours.” At the confluence of the James and Chickahominy, they had discovered the lands of the “Pamaunche” (Pamunkey), rich in “Copper and pearle,” where the people wore copper ornaments in the ears, around their necks, “and in broad plates on their heades,” and where the king had a “Chaine of pearle” worth at least £300 to £400. Finally, during the many feasts and entertainments on the voyage they established cordial relations with Indians on both sides of the river, including a bond of friendship with the “greate kyng Pawatah” himself.16

Having explored further up the river than any previous European, Newport was anxious to mark the achievement with a symbolic monument—setting up a cross with the inscription “Jacobus Rex. 1607.” at the falls—which would serve as a clear signal to other Europeans (but not to the Indians) that the English now claimed possession of all the lands from the entrance of the bay to the mountains. The ritual was accompanied by a solemn prayer for the king's and the settlers' “prosperous succes,” followed by a “greate showte” proclaiming James sovereign. When their Indian guide, Nauirans, grew uneasy at the English celebration, Newport told him “that the two Armes of the Crosse signifyed kyng Powatah and himselfe, the fastening of it in the myddest was their united Leaug [league], and the shoute the reverence he dyd to Pawatah which cheered Nauirans not a litle.”17

Yet appearances were not what they seemed. The limits of understanding gave each side ample opportunity to deceive the other and both took full advantage. To the English, the exploration of the James and the cataloguing of its peoples and natural resources represented essential preliminaries to taking possession of the region. Surveying, measuring, recording were integral to building up knowledge of the land, assessing its potential use and profit, and gauging the military strength of its inhabitants. Equally important was naming (identifying) the natural features and tribes encountered along the way, in some cases adapting Algonquian terms (accommodated to English pronunciation), in others adopting the names of the royal family, prominent lords, and the explorers themselves. Not only the did the imperative of Anglicizing the landscape create recognizable markers and bounds instrumental in the construction of a mental image of the region, it also endowed a strange and sometimes threatening place with a degree of familiarity and provided a comforting reminder of the close links maintained with England across the ocean. Newport had no compunction about misleading the Indians about their true intentions and the meaning of the cross at the falls. Following instructions from the London council not to offend “the naturals,” he deliberately encouraged the impression that his men were more interested in trade than in occupying the land. The London Company recommended that the settlers avoid antagonizing the Indians before the colony was established and able to produce all its own food. Perhaps with the experience of Roanoke in mind, the company's leaders accepted that the colony might well be dependent on the goodwill of local peoples initially, not only for food supplies but also for information about the region and trade.

For their part, the Powhatan Indians deliberately misled Newport about the identity of “Pawatah,” who was in fact one of Wahunsonacock's sons, Parahunt, not the great king himself, and further deceived him by blaming the Chesapeakes for the attack on the English at Cape Henry whereas tribes loyal to the Powhatans were responsible. The generous hospitality extended to the English at the falls and elsewhere during the voyage was merely a subterfuge to keep them upriver long enough for an alliance of five tribes, numbering about two hundred warriors, to launch “a very furious Assault” on the unsuspecting colonists at Jamestown. The attack was beaten off after an hour of intense fighting, largely owing to the murderous effect on the Indians of small shot fired from the ships' cannon.18 Indecisive in military terms, the assault on Jamestown in late May was nonetheless highly significant. English hopes that their arrival in the Chesapeake Bay would be unopposed or even welcomed by local Indians were dashed and it was now clear they had settled in the midst of a powerful alliance.

If the attack on Jamestown had been a temporary setback, nevertheless the English were in an optimistic mood by the time Newport sailed for England toward the end of June. With a touch of exaggeration, the colonists' leaders wrote to the London Company of a land that would eventually “Flowe with milke and honey,” in the form of all sorts of natural products, and hinted at greater discoveries yet to be made in the mountains where perhaps gold was to be found. Archer wrote enthusiastically, “we can by our industry and plantacion of comodious marchandize make oyles wynes soape ashes,…Iron [and] copper,” cultivate sugar canes, olives, hemp, flax, hops, and fruits. He concluded, “I know not what can be expected from a common wealth that either this land affordes not or may soone yeeld.”19

But while in the summer of 1607 the colony's potential seemed boundless, the reality over the next few years proved very different. A deadly combination of disease, Indian attacks, and famine ravaged the settlement and brought the colony to the edge of extinction.

In the first flush of optimism after landing, John Smith described Jamestown as “a verie fit place for the erecting of a great cittie,” but aside from considerations of defense the choice could hardly have been worse.20 The best lands along the river had been occupied for centuries by local tribes, while the site they had chosen was waste ground used by the Paspaheghs for hunting. Large areas of swamp and marshland (natural breeding grounds for swarms of biting insects) rendered half the island uninhabitable and were unsuitable for tillage. The absence of freshwater springs meant that drinking water had to be drawn from brackish wells dug by the settlers or from the river, which in the summer became increasingly saline and polluted. Unknown to the colonists, they had arrived during a severe drought that would make the problem of finding fresh water all the more difficult. Six weeks after Newport sailed for England the terrible roll call began: “The sixt of August there died John Asbie of the bloudie Flixe [flux]. The ninth day died George Flowre of the swelling. The tenth day died William Bruster Gentleman, of a wound given by the Savages, and was buried the eleventh day. The fourteenth day, Jerome Alikock Ancient, died of a wound, the same day Francis Midwinter, Edward Moris Corporall died suddenly.” On August 22 the colony suffered its greatest loss with the death of Bartholomew Gosnold, perhaps the only man who could have held the fractious leaders together. And so through the end of August into September, George Percy wrote, “Our men were destroyed with cruell diseases as Swellings, Flixes, Burning Fevers, and by warres…many times three or foure in a night, in the morning their bodies trailed out of their Cabines like Dogges to be buried…. There were never Englishmen left in a forreigne Countrey in such miserie as wee were in this new discovered Virginia,” he continued in a bitter indictment of the London Company. “Thus we lived for the space of five moneths in this miserable distresse, not having five able men to man our Bulwarkes upon any occasion,” and so weakened by disease “the living were scarce able to bury the dead.” Percy was mistaken in his assumption that “meere famine” was the principal cause of sickness and death. Rather than starvation, the major killer was polluted river water, “full of slime and filth,” which led variously to salt poisoning, dysentery, and typhoid. An epidemic swept the settlement leaving half the 104 men and boys dead before the end of September. By the onset of winter fewer than forty survived.21

Smith's Epic

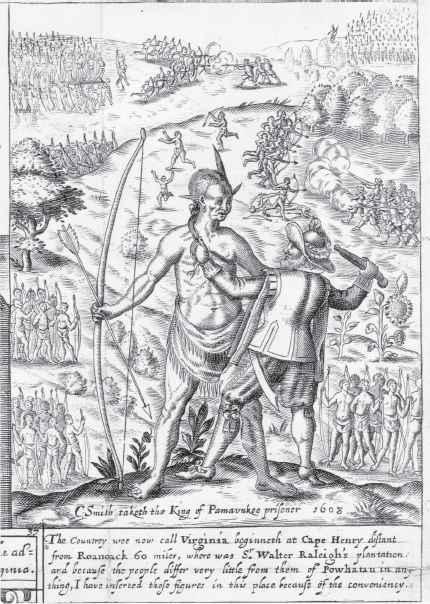

It was against this background of dire necessity that John Smith began trading with the Indians for provisions, first downriver to the large settlement of Kecoughtan and then upriver to the fertile lands along the Chickahominy, where in late December he was captured by the Pamunkey chief, Opechancanough (Figure 1.1). Following several weeks of marches and countermarches back and forth across the frozen landscape between the Pamunkey and Rappahannock Rivers, he was eventually brought into the presence of Wahunsonacock at his capital, Werowocomoco, and received with great ceremony. Smith was the first Englishman to meet the “Emperour” and was impressed by the old man's “grave and Majesticall countenance,” which, he freely admitted, “drave me into admiration to see such a state in a naked Salvage.” In the True Relation, written immediately after the event, he recalled the “great king” told him of the many peoples of the region and lands beyond, including “a fierce Nation that did eate men” and nations to the north, “under his territories,” where a year before they had killed a hundred in battle. “Many Kingdomes hee described mee to the heade of the Bay,” Smith continued, “which seemed to bee a mightie River, issuing from mightie Mountaines betwixt two Seas.” He concluded, “I requited his discourse, seeing what pride hee had in his great and spacious Dominions.” Following an oration along similar lines, wherein Smith recounted the nations subject to his great king (James I) whom he styled “King of all the waters,” Wahunsonacock invited him to “forsake Paspahegh [James Fort], and to live with him upon his River, [in] a Countrie called Capahowsicke.” The offer was not intended to apply to Smith alone, as the following phrase makes clear: “he promised to give me Corne, Venison, or what I wanted to feede us, Hatchets and Copper wee should make him, and none should disturbe us.” Smith and all the settlers would be guaranteed food and safety if they acknowledged Wahunsonacock as their lord and became a subordinate tribe of his chiefdom.22

Figure 1.1. “C[aptain] Smith taketh the King of Pamaunkee prisoner, 1608.” Detail from the plate “Ould Virginia,” engraving by Robert Vaughan in John Smith, Generall Historie (London, 1624). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University. This image represents Smith as considerably shorter than Powhatan's war-chief, Opechancanough, whose hair-lock he grasps in a gesture of dominance. The previous year, it had been Opechancanough who had taken Smith prisoner.

Years later back in England, Smith wrote a considerably more detailed account of the event that included the significant addition of his last-minute reprieve from death by the dramatic intervention of the king's favorite daughter, Pocahontas. Writing in the third person, Smith described what happened:

At his [Smith's] entrance before the King, all the people gave a great shout. The Queene of Appamatuck was appointed to bring him water to wash his hands, and another brought him a bunch of feathers instead of a Towell to dry them: having feasted him after their best barbarous manner they could, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan [Wahunsonacock]: then as many as could lay hands on him dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs to beate out his braines, Pocahontas the Kings dearest daughter, when no intreaty could prevaile, got his head in her armes, and laid her owne upon his to save him from death: whereat the Emperour was contented he should live to make him hatchets, and her bells, beads, and copper.

Destined to take on mythic proportions as a symbol of the transcendent power of love over racial hatred, the truth of Smith's story remains obscure despite the huge volume of writing and controversy it has generated. What is clear from both versions, however, is that Wahunsonacock considered the possibility of sparing the lives of the English by absorbing them into his dominions as a separate people occupying a new tribal territory carved out from the underpopulated lands along the north bank of the lower York. Whether or not he was sincere is as uncertain as Smith's salvation by Pocahontas, but it is likely that, as the colonists' numbers rapidly dwindled during the summer, so his view of them changed: instead of seeing them as a threat he decided the settlers might be of use by providing him with English weapons and copper. With this in mind, he required that Smith send him “two great gunnes” and “a gryndstone” (for sharpening knives and swords) to seal their accord. With abundant English copper to bribe allies and firearms to destroy his enemies there would be no limit to his conquests.23

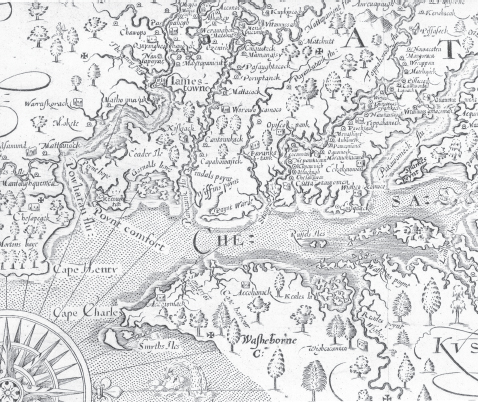

Smith's return to the fort in early January 1608 after a month's absence must have seemed little short of miraculous to his compatriots, who had long since given him up as lost. Not only had he survived unscathed, he brought news of his meeting with Wahunsonacock, a respite from hostilities, and the Indians' promise to supply the starving English with provisions. Taking advantage of the newly established peace, several months later Smith undertook two explorations of the bay that would form the basis of one of the most important achievements of the period: his map and description of Virginia (Figure 1.2). On the first voyage, Smith and fourteen men coasted the Eastern Shore before following the bay northwards for about a hundred miles. After spending a couple of weeks exploring the Potomac, they returned to Jamestown where they arrived on July 21, with the happy news of their discoveries and the hope (“by the Salvages relation”) that the bay stretched far to the west to meet the South Sea.24 Smith did not remain long at the fort but left a few days later to complete his discovery of the bay. On the first expedition he had heard from the Kuskarawoacks of a mighty nation further north called the “Massawomekes” and decided to find them. Accordingly, the expedition made their way to the headwaters of the bay, where they met seven or eight canoes full of Indians they later learned were Massawomecks who spoke a strange language. After exchanging gifts the Indians left and were not seen again, so Smith set course for the Eastern Shore, where they were entertained for several days in the “pallizadoed towne” of the Tockwoughs. There, they were visited by sixty “gyant-like” Susquehannocks, mortal enemies of the Massawomecks, who came with gifts of venison, tobacco pipes, targets (wooden shields), bows, and arrows. The Susquehannocks pleaded with Smith to become “their Governour and Protector, promising their aydes, victualls, or what they had to be his, if he would stay with them, to defend and revenge them of the Massawomeks,” but Smith refused and after learning about a great lake “or the river of Canada” beyond the mountains left them at Tockwough, “sorrowing our departure.”

Having explored the inlets and rivers of the upper bay, Smith and his men returned down the bay to the Patuxent River and then continued on to the Rappahannock River. Sailing their barge as far into the freshes as possible, “there setting up crosses, and graving our names in the trees,” they were suddenly attacked by about a hundred Indians who they learned from a wounded captive were Mannahoacs. From him, further information was gleaned about the peoples and lands of the interior. His people were ruled by the kings of Hasinninga, Stegora, Tauxuntania, and Shakahonea, and their allies, the Monacans, lived close by in the mountains and along the rivers. He knew of the Massawomecks, who, he told Smith, “did dwell upon a great water, and had many boats, and so many men that they made warre with all the world.” Asked why they had attacked them, he answered, “they heard we were a people come from under the world, to take their world from them.” On the final stage of the journey, the company reconnoitered the Piankatank River and then sailed to the south bank of the James to “the country of the Chisapeack,” where entering the Nansemond River, they were attacked by a combined force of several hundred “Chisapeacks” and Nansemonds. Fending off their attackers and threatening to destroy all the canoes they captured, Smith and his men were able to come to terms with their enemies and the following day returned to Jamestown with as much corn as they could carry, thus completing in six weeks a journey that had taken them to the furthest reaches of the bay.25

Figure 1.2. John Smith's Map of Virginia, the tenth and final state of the engraving (1631), currently bound into a copy of Smith's Generall Historie (London, 1624). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University. Unlike modern maps, the top of the page is oriented to the west, not the north. The map shows native villages and chiefdoms as well as new, English place names. The Maltese crosses delineate the boundary between areas Smith and other Englishmen had seen themselves and places they knew only through native informants. This detail shows the area closest to “James' towne” (labeled in large print toward the upper left). Smith's map was originally published in 1612 from a large copper plate engraved by William Hole in Oxford. Over the next two decades, Smith reused the map in other publications and, taking advantage of the malleability of the copper plate, repeatedly updated it, adding new place names as they became available (such as “Washeborne” in the foreground and “Sparkes point” at the mouth of the Potomoc).

Smith and his men were acutely aware of the epic proportions of their two voyages, which were subsequently likened in their writings to famous Spanish discoveries and great feats of exploration in times past. In The Generall Historie, for example, Smith asked: “peruse the Spanish Decades; the Relations of Master Hackluit, and tell me how many ever with such small meanes as a Barge of 2 tuns, sometimes with seaven, eight, or nine, or but at most, twelve or sixteene men, did ever discover so many fayre and navigable Rivers, subject so many severall Kings, people, and Nations, to obedience, and contribution, with so little bloudshed.”26 To ensure their own immortality Smith and his men named (or renamed) the lands and rivers they passed after themselves: the “Sasquesahanocks river we called Smiths falles; the next poynt to Tockwhogh, Pisings poynt; the next it poynt Bourne. Powells Isles and Smals poynt is by the river Bolus; and the little Bay at the head Profits poole; Watkins, Reads, and Momfords poynts are on each side of Limbo; Ward, Cantrell, and Sicklemore, betwixt Patawomek and Pamaunkee, after the names of the discoverers.” The highest mountain they could see to the north, “Peregrines mount,” and “Willowbyes river” were named for Lord Willoughby, lord of the manor where Smith was born. The only casualty of the voyage, Richard Fetherstone, was buried in “Fetherstons bay,” and honored by “a volly of shot.” Where they stopped on their journey or went inland, they left written messages or sometimes brass crosses in holes in trees “to signifie to any, Englishmen had beene there.”27 Whereas Newport and his company had earlier given names to prominent features and the peoples only along the James River, Smith and his men wrote their names across the entire Chesapeake region.

Smith exaggerated when he later wrote he had subjected thirty-five Indian kings to the obedience of the English, but there is little doubt that during the voyages he increasingly took upon himself the role of a plenipotentiary. Time and time again, in a series of encounters that followed a strikingly similar pattern, Smith and his men forced initially hostile tribes to obey the English and sue for peace. Members of the first expedition recalled how “our Captaine ever observed this order to demand their bowes and arrowes, swordes, mantells and furrs, with some childe or two for hostage, whereby we could quickly perceive, when they intended any villany.” Far up the Rappahannock River after a sharp engagement with the Mannahoacs, Smith demanded that their four chiefs surrender their bows and arrows “and then the great King of our [the English] world would be their friend, whose men we were.” A ceremony took place “upon a low Moorish poynt of Land,” where the chiefs and English exchanged gifts, which was followed by much celebration, singing, and dancing by “foure or five hundred of our merry Mannahocks.” Downriver, Smith took on the role of a regional peacemaker in an encounter with the bellicose Rappahannocks, whose chief was also assured of the friendship of King James in return for peace with the English and neighboring tribes. Once again, an exchange of gifts followed by singing and dancing sealed the new accord, this time by six or seven hundred Indians.28

Smith's map, published in 1612 as A Map of Virginia. With a Description of the Countrey, presented to the eye the “way of the mountaines and current of the rivers, with their severall turnings, bayes, shoules, Isles, Inlets, and creekes, the breadth of the waters, the distances of places and such like.” This first attempt to visualize the Chesapeake in detail was hugely influential on cartographic representations of the region for the next seventy years. No one else was able to provide anywhere near such a comprehensive picture of the bay and its peoples. It was a remarkable achievement, surpassing in detail and practical significance, if not aesthetic quality, even the wonderful watercolor maps of Roanoke and the mid-Atlantic coast drawn by John White. Smith gave expression to the sheer expanse of the Chesapeake (approaching a third of the land area of England), the magisterial bay and broad waterways, the myriad creeks and islands, and the numerous tribes and diversity of native peoples. Here was no small island, cramped strip of coast, or minor river valley but an entire country, the bounds of which even Smith had been unable to compass. While at the time of his two voyages the English occupied only tiny Jamestown Island, his map effectively staked England's claim to the whole region, by right of discovery and conquest, and by virtue of English presence in name if not in person.29

Smith's achievements, however, were more apparent to later generations than to his own contemporaries, who had more immediate concerns. The English now had a good idea of the extensiveness of the lands they claimed to possess, but unlike the Spanish in Central and South America they had discovered little of real worth in their new world: no gold, silver, or precious minerals, no convenient access to the Orient, and no advanced Indian civilizations that could be readily plundered. In telling language, the unfavorable comparison with Spanish exploits was recognized by the adventurers themselves:

It was the Spanyards good hap to happen in those parts where were infinite numbers of people, who had manured the ground with that providence, it affoorded victualls at all times. And time had brought them to that perfection, they had the use of gold and silver, and the most of such commodities as those Countries affoorded: so that what the Spanyard got was chiefly the spoyle and pillage of those Countrey people, and not the labours of their own hands…. But we chanced in a Land even as God made it, where we found onely an idle, improvident, scattered people, ignorant of the knowledge of gold or silver, or any commodities, and carelesse of any thing but from hand to mouth, except ba[u]bles of no worth; nothing to incourage us, but what accidentally we found Nature afforded.30

As prospects of quick riches faded it would be Hakluyt's vision, not the example of Spanish conquistadors, that would guide colonists' efforts to produce suitable commodities for sale in England, and for this they needed to occupy the land.

War and Retribution

Shortly after taking charge of the colony in September 1608 following instructions from the Virginia Company, Smith journeyed to Werowocomoco to inform Wahunsonacock that King James had sent him presents to be delivered at Jamestown. In fact, the company had sent gifts to be employed as props (and bribes) at the “coronation” of the Powhatan chief, a ritual intended to confirm their recognition of Wahunsonacock's status among his own peoples while at the same time symbolizing his submission and allegiance to James I. Just as Okisko, king of the “Weopomiok,” had yielded himself “servant, and homager, to the great Weroanza of England [Elizabeth I].” in the final days of the first Roanoke colony, so Wahunsonacock was called upon to play the part of a local lord under the authority of the English king and his envoys in Virginia.31 Barely nine months before, during Smith's captivity, the great chief had offered to support and protect the colonists if they submitted to his rule; now the English had brazenly turned the tables. Wahunsonacock, however, was reluctant to play the role assigned to him. Replying to Smith's invitation to come to Jamestown, he responded: “If your king have sent me presents, I also am a king, and this my land, 8 daies I will stay [at Werowocomoco] to receave them. Your father [Newport] is to come to me, not I to him.” Accordingly, Newport and Smith accompanied by fifty men made their way to the Powhatan capital where the gifts—a bason, ewer, bed, and bedclothes—were put on display. The coronation itself proved a farce. Wahunsonacock would only consent to wear the “scarlet cloake and apparel” brought by the English for the purpose after being assured they would do him no harm, but even worse he refused to kneel to receive his crown, “neither knowing the majestie, nor meaning of a Crowne, nor bending of the knee…. ” After “many perswasions, examples, and instructions, as tired them all,” Newport, “by leaning hard” on the king's shoulders managed to get him to stoop a little “and put the Crowne on his head.” In his honor, the English fired a volley which caused “the king [to] start up in a horrible feare,” but seeing all was well he thanked the English and “gave his old shoes and his mantle [cloak] to Captain Newport.”32

Smith, a relentless critic of Newport and company policy, had been highly skeptical of the “strange coronation,” because the colonists in his opinion had the king's favor “much better, onlie for a poore peece of Copper,” whereas “this stately kind of soliciting made him so much overvalue himselfe, that he respected us as much as nothing at all.” But Wahunsonacock was far more astute than either Smith or Newport gave him credit. The coronation had cost him nothing. He had made the English come to him, accepted their gifts, and in return given them merely some old clothing, (their value presumably residing in the fact they had been close to the royal body). He had confirmed his prestige in the eyes of his own people by inverting the meaning of the ritual: it was he who received the acclamation and homage of the English, not the other way round. Smith was doubtless right in his observation that Wahunsonacock did not understand the symbolism of the crown or the act of receiving it. But more accurately, the Powhatan king did not accept the English meaning of the ritual, just as (apparently) the English completely misunderstood the significance the Indians attached to the event.33

From both sides' point of view, the coronation was yet another example of charade masking intent. Newport was no Virginia king-maker. The crown had been proffered not in recognition of Wahunsonacock's title to royalty but to confirm the Indians' status as vassals of the English. For his part, the Powhatan chief had already decided to rid himself of the troublesome intruders by cutting off food supplies. Several reasons prompted his decision. Whatever he thought about the chances of the small English contingent surviving long or of the potential value of the trade in European goods, particularly weapons, his overriding concern must have been for the security of his territories and his own position as chief of chiefs. The arrival of more settlers in 1608 may have convinced him that the English posed more of a threat than a benefit. “Many do informe me,” he told Smith in the fall, “your comming is not for trade, but to invade my people and Possesse my Country.”34 Under these circumstances it was imperative to take action against the newcomers, and that such action be seen as a warning to any petty chiefs who might have considered siding with the English against him. The nature and recent development of his empire largely dictated his course of action. He could not tolerate a powerful independent people planting themselves in the midst of his lands, and the combination of war, threats, and fear that held together his dominions determined that if the English could not be controlled they must be confronted.

About the same time, the Virginia Company came to a similar conclusion. If the Indians would not accept English rule by persuasion they would have to be subdued by force. A new charter endowed the colony's governor with near absolute powers, and the company began recruiting veteran officers from campaigns in Ireland and the Netherlands to take charge of affairs, men such as Sir Thomas Gates, Lord De La Warr, and Sir Thomas Dale. The decision had not been taken lightly, and followed an intense debate among company members about how to justify military action and the importance of avoiding the bloody excesses that characterized the Spanish. As the project of colonization took on a militant Protestant tone, so it became more closely linked in the English mind to an evangelical crusade. Conversion must follow conquest. “Our intrusion into their possession shall tend to their great good,” Robert Johnson believed, “our comming hither is to plant our selves in their countrie: yet not to supplant and root them out, but to bring them from their base condition to farre better.” Robert Gray put the matter more bluntly. Christian kings may lawfully make war on savage peoples providing the ultimate objective was to reclaim them from their barbarous ways. “Those people are vanquished,” he wrote in a memorable turn of phrase, “to their unspeakable profite and gaine.”35

A force of nine ships carrying some 500 men commanded by Gates and Sir George Somers was dispatched from London in May of 1609. Gates was instructed by the Virginia Company to take Wahunsonacock prisoner or render him a “tributary,” and to require his chiefs to acknowledge no other lord but James I. Priests and chiefs were to be removed from the people and taken into custody, and the young brought up in the manners and religion of the English. Thereby, it was anticipated that the “people will easily obey you and become in time civill and Christian.” The company further advised that the colonists abandon fair trade and get food from the Indians by force, since “they will never feede you but for feare.”36 Hostilities broke out shortly after the arrival of the “third supply,” six of the original nine ships carrying about 250 settlers (the remainder of the fleet had been shipwrecked on Bermuda and would not arrive in Virginia for another ten months). Food shortages at Jamestown persuaded Smith to disperse some of the colonists downriver near the Nansemonds' village at the entrance of the James and others upriver near the falls, where he established his men in the fortified village of Powhatan. English aggression in stealing corn, attacking villagers, and burning their houses led to swift revenge by Indian warriors, forcing the settlers to return to the ill-provisioned Jamestown after sustaining heavy losses. Having confined the English to the fort, and deciding against a frontal assault, Wahunsonacock's warriors sealed off the island in an attempt to starve the English into submission. During the siege of Jamestown from November 1609 to May 1610 about half the garrison died of disease and malnutrition, were killed as they tried to escape, or were slain after putting “themselves into the Indians handes, though our enemies.”37

These were among the most harrowing times of Virginia's troubled early history, exceeding even the horrors of the settlers' first summer. Once again, it was George Percy who recorded the “worlde of miseries” they endured. To satisfy their “Crewell hunger,” he wrote, they ate their horses and dogs, vermin around the fort such as rats and mice, and when these ran out even their boot leather. In desperation, some went beyond the palisade into the woods in search of “Serpents and snakes, and to digge the earthe for wylde and unknowne Rootes where many…weare Cutt off and slayne by the Salvages.” But worse was to come as weeks turned into months. Percy recalled, “And now famin begineinge to Looke gastely and pale in every face thatt notheinge was spared to mainteyne Lyfe and to doe those things which seame incredible As to digge up dead corpses outt of graves and to eate them and some have Licked upp the Bloode which hathe fallen from their weake fellowes.” To prevent the colony falling into complete disorder, martial law was enacted. Anyone caught stealing from the common store was executed; a man who murdered his wife and ate her was tortured to extract a confession and then dealt with similarly.38

When Gates arrived in May 1610 the “sixty” survivors were in such a terrible condition “itt was Lamentable to behowlde them.” Many, through extreme hunger, “Looked Lyke Anotamies [anatomies] Cryeinge owtt we are starved We are starved.” One Hugh Price, “In A furious distracted moode did come openly into the markett place Blaspheameinge exclameinge and cryeinge owtt that there was noe god. Alledgeinge that if there were A god he wolde nott suffer his creatures whom he had made and framed to indure those miseries.” The palisades of the fort had been torn down, entrances left open, and houses “rent up and burnt” for firewood. William Strachey observed “the Indian killed as fast without,” if men went beyond the fort, “as Famine and Pestilence did within.” In “this desolation and misery,” Gates considered he had no other choice but to abandon the colony. After burying their cannon “before the Fort gate” (an indication that abandonment was seen as temporary), the English left Jamestown at midday on June 7 and sailed downriver to Hog Island. Having arrived three years earlier to the sound of trumpets, the English marked their departure by the somber beat of the drum and a volley of small shot.39

The following day, however, a remarkable turnabout occurred. Continuing down the James River, Gates and his small flotilla were met by an advance party of the new governor, Thomas West, Lord De La Warr, who had recently entered the bay with three ships and 150 colonists, two-thirds of whom were soldiers. De La Warr's arrival saved the English colony and in the long run proved decisive in the war against the Powhatans. Taking the offensive for the first time in nearly a year, the English organized themselves into military companies and conducted a series of devastating and brutal raids on neighboring Kecoughtans, Paspaheghs, Chickahominies, and Warrascoyacks, during which they adopted a scorched earth policy reminiscent of campaigns in Ireland in the 1590s and put to the sword men, women, and children. Villages were burned to the ground, “Temples and Idolls” destroyed, and ripening corn carried away. The following year, between April and August 1611, another six hundred colonists arrived with a “greatt store of Armour, Municyon[,] victewalls,” and other provisions, enabling English commanders to continue their destructive raids on tribes all along the James River from its mouth to the falls.40

No decisive battle marked the end of the war, but English success in establishing themselves upriver at Henrico, downriver near the Indian town of Kecoughtan, as well as on Jamestown Island was abundantly clear to Wahunsonacock by 1614. Refusing to surrender formally, he had nevertheless come to accept that his warriors were incapable of dislodging the invaders from his lands. For their part, the English considered the victory theirs. They had successfully fended off the Powhatan threat and consolidated their hold on the colony. They had also entered into alliances with tribes on the Eastern Shore and concluded articles of peace with the powerful Chickahominies, who adopted the English king as their overlord. A pamphlet of 1616 confidently asserted that the colonists were “by the Natives liking and consent, in actuall possession of a great part of the Countrey.”41 The marriage of Wahunsonacock's favorite daughter, Pocahontas, to an English gentleman, John Rolfe, in April 1614 symbolized the new accord between the two peoples, who now (seemingly) lived side by side in harmony and friendship as one nation.

But the question remained: whose nation? Wahunsonacock had tacitly agreed to live in peace with the English but had not relinquished his title to the region nor acknowledged James I his king, and if a number of tribes had transferred their allegiance to the English during the war, nevertheless the core of his empire remained intact. Seduced by their own propaganda, which lauded the praises of the new colony, and enjoying the fruits of prosperity as a result of the adoption of tobacco cultivation, the English were completely duped by the great king's effective successor, Opechancanough, and lulled into a fatal sense of false security. The great uprising of March 22, 1622 left 347 settlers dead, about a quarter of the entire colony, and was a defining moment in Anglo-Indian relations in early America. It removed any moral obligation from the English (in their view) to continue their self-imposed labor of bringing civility and Christianity to the Indian.42 English policy did not change significantly after 1622, in the sense that the second Anglo-Powhatan war was in many respects a continuation of the first, but any hopes that the two peoples could live together in peace were utterly confounded by what propagandist Edward Waterhouse called the “barbarous Massacre.” By “this last butchery,” Samuel Purchas fulminated, the Indians “made both of them and their Country wholly English.” They could be cleared from the land in the knowledge that “having little of Humanitie” they had given up their right to be treated like humans. “Our first worke,” governor Sir Francis Wyatt wrote from Virginia in 1623 or 1624, “is expulsion of the Salvages to gaine the free range of the countrey for encrease of Cattle, swine &c which will more then restore us, for it is infinitely better to have no heathen among us, who at best were but thornes in our sides, then to be at peace and league with them.” To English eyes, the uprising fully justified the dispossession of the Indians. As Waterhouse argued: “our hands which before were tied with gentlenesse and faire usage, are now set at liberty by the treacherous violence of the Savages…so that we, who hitherto have had possession of no more ground then their waste…may now by right of Warre, and law of Nations, invade the Country, and destroy them who sought to destroy us.” The subjugation of the Indians as a conquered people was taken for granted and their removal from English lands proceeded with gathering pace through the 1620s and 1630s. A final desperate act of resistance led by Opechancanough was mounted in 1644, but the country had already been lost and with it the Powhatan empire.43

Conquest and Dominion

The twin imperatives of conquest and dominion are of importance in explaining Anglo-Indian encounters in early America, influencing English policy toward colonization, and shaping Indians' attitudes to the strangers who had come into their lands not just to trade but to settle. From this point of view, the descent into violence that characterizes relations at Roanoke and in the Chesapeake was not just the inevitable outcome of English aggression toward peoples they considered culturally inferior, a consequence of the breakdown of trade, or an expression of the Indians' defensive reactions to European invaders. Negotiations and eventually hostilities were structured on both sides by a powerful sense of territory and sovereignty.44 In Virginia, colonists encountered an aggressive and skilful chief who at least initially may have entertained the possibility of absorbing the English settlers into his domains. If Wahunsonacock believed the colonists' stories of a great king across the water, he evidently did not consider that settlers should necessarily remain subject to such a distant authority, any more than he could conceive of English claims to his lands or their expectation he should conform himself to English governorship. He had told John Smith at the mock coronation that he was already a king and the lands surrounding them were his. But when he reminded Smith that he was one of his chiefs, Smith told him: “you must knowe as I have but one God, I honour but one king [James I]; and I live here not as your subject, but as your friend.” Sovereignty was indivisible; there could be no compromise.45 This was the crux of the matter. Neither Smith nor any other English leader could transfer his allegiance to an Indian king, any more than Wahunsonacock could accept the sovereignty of the English monarch. Since neither side was capable of comprehending the basis of the other's claims, arguments and counter-arguments were soon overtaken by violence, war, and the forcible dispossession of Indians hostile to the English. Smith was astute in his observation that the Indians “were our enemies, whom we neither knew nor understood,” but equally the Powhatans had no means of understanding the English compulsion to claim Virginia as their own. In these circumstances, a bloody struggle for possession was inevitable.