Chapter 2

Powhatans Abroad

Virginia Indians in England

In the summer of 1603, an English expedition brought two or three natives of Powhatan's domain to London, where in September the captive “Virginians” paddled a canoe on the Thames before a rapt audience. That event inaugurated—several years before Captain John Smith and his companions secured a foothold in Virginia—the human exchange between Powhatan's Tsenacommacah (“densely inhabited land”) and King James's England.1 Although the movement of peoples would in the long run be dominated by thousands of English men and women making permanent homes in Virginia rather than two dozen Powhatans residing temporarily in England, the thinner eastward current would play a significant, if unheralded, part in the Atlantic world's cultural interaction.

The captives of 1603 are notable not only for their chronological primacy but for having been taken to England by force. Most of the subsequent eastward voyagers before the demise of the Virginia Colony as a corporate enterprise went willingly, the surviving records suggest, either as envoys of Chief Powhatan or as temporary guests of the Virginia Company of London. The few but important Indians in the first category served Tsenacommacah by scouting the English colonists' homeland for information about its people and resources. The second and larger category consisted of Virginia Company recruits for English schooling and conversion to Christianity. A notable exception to the two paradigms was Pocahontas, the Powhatan princess whose presence in England demonstrated the colony's missionary potential. Regardless of the circumstances behind their transatlantic travels, Indians in England before 1624 gave thousands of English people a first-hand impression of American natives and, through them, some inkling of Powhatan culture.

The Virginians who exhibited their skills on the Thames in 1603 are a hazy initial episode in the story of Tsenacommacah's inhabitants abroad. The precise circumstances of their seizure are unknown; their voyage and initial reception in England are undocumented; and, after a moment's fame on the Thames, they drop from sight.2 The sole record of their English experience is Sir Robert Cecil's list of “rewardes” for services rendered to his London household, which shows payments of four and five shillings during the first week of September 1603 “to the virginians”; the actual disbursement was probably by Sir Walter Cope, who seems to have supervised the Indians in London. Another five shillings were “geven by Myles [surely a Cecil employee] to ii watermen that brought the cannowe to my Lords howse” on the Strand, and twelve pence “to a payre of ores[men] that waited on the Virginians when they rowed with ther Cannow.”3 No further evidence illuminates Tsenacommacah's first migrants to England.

What these Virginians observed in their London stay can only be surmised, but there are grounds for informed guesses. Nearly a score of American natives had been in England during the previous two decades, all of them apparently persuaded, or forced, to leave their homelands to serve their hosts' pragmatic purposes. Leaving aside the eight or so who arrived before 1577 (information on them is sparse; half died within a month), the Indians in England between that date and 1603 were interrogated about their homelands, indoctrinated in English customs, taught the English language, and sent back with new expeditions as interpreters, guides, and liaisons to their own and neighboring peoples. From the experiences of these American natives, and by extrapolating from the evidence on five Abenakis from the “northern parts of Virginia” (renamed New England in 1616) who arrived in 1605, the expectations for Cope's Virginians of 1603 can be readily surmised.4

The most exemplary early American visitor, from England's perspective, was Manteo of Croatan Island, who learned English in London from the linguistically talented Thomas Hariot in 1584–85, then served as interpreter, guide, and diplomat for the first Roanoke Island outpost in 1585–86. After another journey to England in 1586–87, Manteo returned to Roanoke with the “lost” colony of 1587 and probably shared its fate. Manteo’s companion of 1584–85, the Roanoke native Wanchese, vehemently opposed English settlements after completing his transatlantic round trip, but he was a notable exception in the pre-1603 roster of Indian intermediaries.5 The two other Indians from the Carolina coast who were in England in the 1580s seem to have assisted the English. Towaye probably accompanied Manteo on his second trip to England and definitely returned with him to Roanoke in 1587, perhaps as a second interpreter. The other Indian, seized by Sir Richard Grenville in 1586, was likely preparing to accompany Grenville's aborted relief expedition to Roanoke in 1588 when he succumbed to disease.6 English-trained Indians had not saved the Roanoke outposts from disaster, but they had been valuable to the colonial enterprise.

Sir Walter Ralegh's explorations in the Orinoco River valley in the 1590s reinforced the point. The ten or so natives of Trinidad and Guiana taken to England by his agents in 1594 and 1596, and by Ralegh himself in 1595, became interpreters of varying proficiency, their linguistic skills contingent, most likely, on the duration of their stays abroad. John Provost of Trinidad, for example, served Ralegh's nephew Sir John Gilbert “many yeeres” in England and in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries was a reliable interpreter and guide in Guiana to several English scouting parties and to at least one incipient English outpost. He also persuaded wary Guianan natives that the English, unlike the slave-raiding Spanish, should be welcomed as peaceful and potentially useful visitors.7 Surely Sir Robert Cecil had similar roles in mind for the Virginians who plied the Thames in 1603.

Why none of those Indians were aboard the Susan Constant, Godspeed, or Discovery when Christopher Newport's little fleet sailed from London in December 1606 is unknown but easily imagined. The South Americans, even if willing, would have been irrelevant in Tsenacommacah's unfamiliar geographic and linguistic setting. Cope's Virginians most likely had not survived the plague of 1603, which killed thousands of Londoners that summer and frightened many of the gentry and nobility into temporary exile. (King James left London in early August; Lord Cecil was miles away when the Indians lodged at his house.8) If the Virginians somehow survived the plague and subsequent diseases, they may have returned to the Chesapeake on an unrecorded voyage between 1603 and 1606. In the latter year, the Virginia Company of London's counterpart for the settlement of the area north of the Hudson River assigned several captive New England Algonquians, seized in 1605, to its two scouting expeditions and other Indians to a colonizing expedition in 1607. A Spanish fleet captured the two Indians who sailed on the first of those voyages, but their compatriots on the second and third performed the intended roles moderately well at the short-lived Sagadahoc Colony in Maine.9 The absence of one or more Indian guides on Christopher Newport's fleet of 1606–7 is therefore surprising and can only mean that no qualified Virginian was available. Jamestown's troubled early history would illustrate, by their absence, the usefulness of cultural intermediaries.

Powhatan's Envoys

In early 1608, a few weeks after Powhatan's famous first confrontation with John Smith, the sachem dispatched his envoy Namontack “to King James his land, to see him and his country, and to returne me the true report thereof.”10 Smith described Namontack as the chief's “trustie servant, and one of a shrewd subtill capacitie,” although he was often referred to—figuratively in some accounts, literally in others—as the chief's son. As a hostage to Namontack's safe return, the Powhatans received from Captain Christopher Newport a linguistically ironic swap: for the “savage” (in English parlance) Namontack they acquired a thirteen-year-old English lad named Thomas Savage, introduced to Powhatan as Newport's son.11 He would spend the next three years with the Virginia Algonquians, learning their language, observing their customs, and endearing himself to Chief Powhatan. After Savage's return to Jamestown in about 1611, he translated for the colony often and well until his death in the early 1630s.12 Thus the paramount chief of Tsenacommacah and the leader of the English outpost each used a surrogate son to glean information about the other's customs, resources, and intentions.

At this early stage of English colonization, Powhatan had no reason to fear for Tsenacommacah's future. The hundred or so colonists at Jamestown seemed unlikely to survive: always short of food, badly sheltered, and scarcely able to defend their small enclave, despite their thunderous weapons, gigantic (to Indian eyes) vessels, and self-assumed cultural superiority. By the time Namontack reached Jamestown in early March 1608, fire had destroyed most of its crude buildings, “which being but thatched with reeds,” remembered one of the colonists, “the fire was so fierce as it burnt their Pallisado's, (though eight or ten yards distant) with their Armes, bedding, apparell, and much private provision.” In the ensuing weeks of bitter cold and extreme shortage of food, half the colonists died.13 Long before Namontack boarded Newport's ship, he must have expected to be unimpressed by England.

In London, Powhatan's first appointed envoy to Whitehall made quite a stir. The Venetian ambassador informed his government that a leading inhabitant of Virginia had arrived “to treat with the King.” Pedro de Zuniga, Spain's ambassador to England, notified Philip III that “Newport brought a lad who they say is the son of an emperor of those lands” who had been instructed “that when he sees the King he is not to take off his hat, and other things of this sort.” Zuniga was “amused by the way they [English authorities] honour him, for I hold it for surer that he must be a very ordinary person.”14 Such European preoccupation with Namontack's social status is telling. If the Venetian and Spanish ambassadors reported accurately the English perceptions of this Tsenacommacah native, his billing as the son of an emperor made him mildly important; what his hosts might learn from him about the American environment or Powhatan culture seemed to matter very little. Namontack was not, to be sure, the first Indian in England, nor even the only one there (in 1608 he shared the exotic limelight with a few natives of New England and several of Trinidad and Guiana), but he was the first voluntary envoy from the area of England's sole existing outpost. English authorities should have cared.

No accounts survive of Namontack's activities abroad. He must have seen London's notable sights and perhaps glimpsed other parts of England. That he had an audience with King James is doubtful, absent any record of the event, though he may have spotted the monarch in a passing carriage, and he surely met officials of the Virginia Company of London. That Powhatan's envoy was topical is nonetheless evident from the character in Ben Jonson's Epicoene (1609), who drew a “map or portrait” of Namentack when he was there.15 Of greater importance for the Powhatans, Namontack must have made extensive mental notes on the English capital—its teeming population compared to Tsenacommacah's, its multistoried buildings, its innumerable ships, its pomp and ostentatious wealth; but also its gagging odors, littered streets, and widespread, sometimes lethal poverty. Namontack surely carried home an ambivalent description of Captain Newport's nation. In any event, the envoy's stay lasted only four months. Newport sailed from England in mid-July 1608 with Namontack aboard and reached Jamestown in late September.16 A few weeks later, John Smith visited Powhatan at Werowocomoco and “redelivered him Namontack he had sent for England.”17

Back in Tsenacommacah, Namontack spoke favorably of his experience. Francis Magnel, an Irishman who spent eight months in Virginia, reported that “The Emperor [Powhatan] sent one of his sons to England, where they treated him well, and sent him back to his land. The Emperor…and his people were very happy over what he told them about the good reception and entertainment he found in England.”18 And Namontack was sufficiently trusting of English customs to play a crucial role in Newport's “coronation” of Powhatan as King James's Virginian vassal—a role the supreme sachem of Tsenacommacah had no intention of playing. A suspicious Powhatan acceded to the ceremony only when “perswaded by Namontack they would not hurt him.” Weeks later, Namontack helped the hungry colonists obtain several hogsheads of corn despite Tsenacommacah's renewed hostility to the English intruders.19 From that point on, Powhatan's first envoy to England is primarily notable for the uncertainty of his fate and for his embodiment of the evidential confusion that shrouds early Indian transatlantic travel.

Despite Smith's assurance that he “redelivered” Namontack in the autumn of 1608 and sure signs that Namontack was at Tsenacommacah later that autumn, he seems to have disappeared. In 1614 Powhatan complained to secretary of the colony Ralph Hamor that after Namontack went to England in exchange for Thomas Savage, he “as yet is not returned, though many ships have arrived here from thence, since that time, how ye have delt with him I know not.”20 Smith later provided a possible explanation. In his Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624), Smith ended a brief, second-hand narrative of Sea Venture's wreck on Bermuda in 1609 with a grim scenario: “There were two Salvages also sent from Virginia by Captain Smith, the one called Namuntack, the other Matchumps, but some such differences fell betweene them, that Matchumps slew Namuntack, and having made a hole to bury him, because it was too short, he cut of[f] his legs and laid them by him, which murder he concealed till he was in Virginia.”21 A year after the publication of Smith's history, the Reverend Samuel Purchas corroborated the story. In reprinting an early Virginia assertion that among the Powhatan Indians “Murther is scarsly heard of,” Purchas added a marginal note: “Yet Namantack in his returne was killed in Bermuda by another Savage his fellow.”22

Perhaps Smith and Purchas were right. Newport departed Virginia on his third trip to England in December 1608 and probably arrived before mid-January 1609.23 If Namontack accompanied him a second time and Matchumps went with them, the two Powhatans could have boarded Sea Venture in early June 1609 and, along with all passengers and crew, survived its crash off the Bermuda coast in late July. Matchumps had abundant opportunity to kill Namontack during the ten months in which Admiral George Somers directed the building of two small ships for the final leg to Jamestown. But undermining the plausibility of an Indian versus Indian crime on Bermuda in 1609 is the absence of any reference to Namontack or Matchumps, either by name or ethnicity, in the many contemporaneous accounts of Sea Venture's wreck and its aftermath. Some chroniclers might have considered two Indians of slight importance; for English writers and readers, the central message of England's tempestuous rediscovery of Bermuda was God's merciful rescue of one hundred and fifty terrified souls on an island paradise that was widely reputed to be the “Isle of Devils.” But why would one of the survivors, the learned William Strachey, whose very long letter of 1610 to an anonymous “Excellent Lady” abounds with the Bermuda episode's people and events, have overlooked the presence of two Virginia natives on an archipelago which almost miraculously had no natives of its own? And would Strachey not have mentioned Namontack's conspicuous absence when the survivors sailed on to Jamestown in 1610, while relating that two Englishmen, one a murderer, were left behind? Such omissions seem improbable by an author whose Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania, written no more than two years after he and the other Bermuda survivors reached Virginia, mentions both Matchumps and Namontack, with no hint of an altercation between them or of the latter's demise.24

The soundest surmise from the scraps of conflicting evidence on Powhatan's first envoy to England may be that in 1608 Namontack spent about four months in England, where he was well treated and returned home with useful information; that during the next few months he assisted in Powhatan's coronation and served as a guide and interpreter to the colonists. He then probably went to England a second time, perhaps in late 1608—possibly a year or two later—and had not returned to Tsenacommacah by 1614. He may have been killed by Matchumps on Bermuda in 1609 (despite no mention in the reports) or slain by Matchumps at a later date on the Bermuda Islands or elsewhere, with Smith entering a garbled report at the end of his account of the Sea Venture episode and Purchas uncritically adopting Smith's explanation. But whatever his fate, Namontack is the first envoy from North America to observe England and report his findings to the indigenous side of the incipient British empire.25

A few more Powhatans followed Namontack's path to England before 1616, although the intermittent Anglo-Indian wars allowed scant opportunity for ambassadorial visits, and the circumstances of most Indian travels are unclear. In 1610, for example, Strachey mentioned Powhatan's displeasure with Jamestown's leaders for not giving him a coach and horses, “for hee had understood by the Indians which were in England, how such was the state of great Werowances, and Lords in England, to ride and visit other great men.” In addition to Namontack, Powhatan's informants could have been Powhatan's brother-in-law Matchumps, who, according to Strachey, “was sometyme in England,” and Kainta, son of a local chief, captured by the English during one of the internecine wars, and “sent now [ca. July 1610] into England, untill the ships arrive here againe the next Spring.”26 Nothing further is known about Kainta's travels or his presumed return to Virginia after about eight months abroad. Why colonial officials sent this captive to England is unknown. He must have been there too briefly to master the English language, though he probably learned enough to be useful to Powhatan; he could have been exposed to intensive questioning and indoctrination; and eight months was surely long enough for any American visitor to observe that the aristocracy traveled by horse and carriage. Or perhaps Kainta was primarily a curiosity, a symbol of the colony's power to seize and transport a “savage” prince—another Virginian on display.

The “Indian College”

By the time Kainta arrived in England, the linguistic training of Indians abroad no longer retained the urgency it had held at Roanoke and Guiana. In Virginia, Thomas Savage and several other colonists were now adept at the Powhatan language and presumably more loyal to colonial interests than Indians educated in England were likely to be. But the conversion and education of the Powhatans and their neighbors was another matter. The colony had few clergymen and no schools and thus no practical way to fulfill the Virginia Company of London's obligation to “bring the infidels and salvages, lyving in those partes, to humane civilitie.” A pamphlet addressed to the Virginia Company insisted that it is “not the nature of men, but the education of men, which make[s] them barbarous and uncivill”; if you “chaunge the education of men…you shall see that their nature will be greatly rectified and corrected.”27 The best place to instill civility and Christianity, English imperialists believed, was England, though it was worth a try in Virginia.

A plan to indoctrinate Indians in England was underway by the early summer of 1609. Shortly before Sir Thomas Gates boarded the Sea Venture, the London Company advised him to “procure…some convenient nomber of their Children to be brought up in your language, and manners.” After Gates was presumed to have been lost at sea, the company sent Sir Thomas West, Lord De La Warr, to administer the colony; if Indian leaders “shalbe willfull and obstinate,” he was to seize Indian shamans and “send over some three or foure of them into England [so that] we may endevour theire Conversion here.”28 Although intermittent war with the Powhatans prevented the full implementation of those instructions, a trickle of potential Indian converts across the Atlantic began about 1610. Kainta may have been the first.

Once again, the particulars are obscure. The earliest recruit, if not Kainta, was probably “one Nanawack, a youth sent over by the Lo. De Laware, when hee was Governour there,” according to a pamphlet of 1630, harking back to De La Warr governorship in 1610–11. If conversion was the goal for Nanawack, it failed initially, for “living here a yeare or two in houses where hee heard not much of Religion, but saw and heard many times examples of drinking, swearing, and like evills, [he] remained as hee was a meere Pagan.” A change of venue made all the difference. With the boy “removed into a godly family, hee was strangely altered, grew to understand the principles of Religion, learned to reade, delighted in the Scriptures, Sermons, Prayers, and other Christian duties, wonderfully bewailed the state of his Countrymen, especially his brethren; and gave such testimonies of his love to the truth, that hee was thought fit to be baptised.” As often happened to Indians abroad in the seventeenth century, death intervened. His hosts were nonetheless impressed by the depth of Nanawack's faith, for he “left behinde such testimonies of his desire of Gods favour, that it mooved such godly Christians as knew him, to conceive well of his condition.”29

The London Company's long-range plan was to enroll Powhatans at a school and college in Virginia, where academic studies would complement the training in religion and manners. A colony law of August 1619 directed each town and plantation to “obtaine unto themselves by just meanes” several Indian youths for exposure to “true Religion & civile course of life. Of which children the most towardly boyes in witt & graces of nature [are] to be brought up…in the firste Elements of litterature, so as to be fitted for the Colledge intended for them.” College education would, of course, extend beyond English literature to Latin and Greek, as would a preparatory school's lessons, if a prominent English educational reformer had his way. John Brinsley advocated high quality grammar schools as the antidote to the “inhumanitie” exhibited by “manie of the Irish, the Virgineans, and all other barbarous nations,” in accordance with Ovid's judgment that “Right learning of ingenous Arts, / The savage frames to civill parts.” But not until 1620 would the company have sufficient funds to begin either an Indian school or a college.30

In the meantime, several Powhatans followed in Kainta's and Nanawack's footsteps. In 1617 Samuel Purchas observed that the sponsors of Virginia's intended Indian college had “brought thence children of both sexes here to be taught our language and letters, which may prove profitable instruments in this [educational and missionary] designe.” Just who those Indian children were—their names, ages, dates, and circumstances of migration—is unknown. They must have been few in number, given most Indian parents' reluctance to part with their children and the paucity of references in the surviving records to Indian youths in England. Two burial records for a London parish in 1613 may pertain to such visitors: entries for October 28 and November 4 read identically: “A Virginian, out of Sir Thomas Smithes howse.”31 While “Virginian” in 1613 could still refer to an Indian from anywhere along the eastern coast of North America between Florida and Canada, none outside of the Virginia Company of London's territory—that is, the Virginia Colony and its environs—would likely have been living at the home of the company's president. Perhaps the two Indians who died in 1613 were adult Virginians whose arrival in London is undocumented; one may have been Nanawack. The most plausible explanation is that they were two of the anonymous youths sent to England by Lord De La Warr and his successors for schooling and conversion.

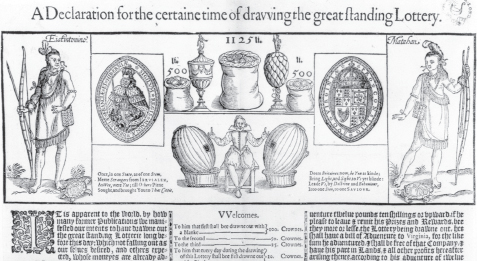

Two young males from Tsenacommacah, probably part of the missionary/ educational contingent, had their likenesses widely distributed in Jacobean England. In early 1615, the Virginia Company issued “A Declaration for the certaine time of drawing of the great standing Lottery,” a moderately successful bid to raise funds for the corporation's general expenses and especially its missionary work (Figure 2.1). This large broadside featured two full-length drawings of Virginia Indians: on the upper left corner is Eiakintomino, facing to his left and holding a bow and arrows, wearing a fringed mantle and purse, with a turtle near his left foot. On the upper right hand corner, Matahan has a similar pose, garment, accoutrements, and turtle, but he faces to his right and has a slightly different feathered ornament in his hair. The first four lines of a poem which supposedly expressed the Virginians' Christian longings are near Eiakintomino's feet, the other four lines near Matahan's. The whole text reflects English expectations of imminent Indian conversion to Anglicanism and a current English penchant for comparing the Indians' presumed lack of civility to the ancient Britons' before the Roman conquest.32

Although there is no proof that Eiakintomino and Matahan posed in England—adaptations of illustrations by John White and others proliferated for centuries without the artists seeing an Indian—there is reason to believe that these Indians were in London in 1615 or earlier. Almost contemporary with the lottery broadside is the Dutch artist Michael van Meer's full-length watercolor portrait of Eiakintomino in St. James Park, flanked by five large fauna. The handwritten Dutch caption identifies the scene as “A young man from the Virginias” and, elsewhere on the picture, “These Indian birds and animals [in fact, they are European rather than “Indian”], together with the young man, were to be seen in 1615, 1616 in St James Park or zoo which is [illegible] near Westminster before the city of London.”33 No evidence survives about Eiakintomino's and Matahan's fate.

Figure 2.1. The Virginia Company of London, “The Great Standing Lottery,” broadside (London, 1615), detail. Courtesy of the Society of Antiquaries of London. This larger broadside advertised a lottery to raise money for the Virginia Company and features portraits of two Virginia natives: Eikintomino on the left and Matahan on the right. The text promotes the idea that the Virginia colony will benefit the region's natives: they are depicted as eager to convert to English ways and adopt the English religion. The verse at the men's feet reminds readers that the English themselves were at one time pagans, and begs them to “Bring Light and Sight to Us yet blinde.”

Their lives in England must have overlapped with several youths in the delegation of Powhatans, featuring Pocahontas, assembled by Sir Thomas Dale in 1616. Tomocomo (a.k.a. Uttamatomakkin, Tomakin), Pocahontas's brother-in-law and her most prominent native companion on the great promotional visit of 1616–17, lamented to Samuel Purchas that he was himself too old to learn a new religion, “bidding us teach the boies and girles (which were brought over from thence).” Tomocomo may have referred to Indians who had been sent earlier, but other potential students surely accompanied him to England. In June 1616 a Londoner noted that Dale “hathe brought divers men and women of that countrye to be educated here.”34

Another Englishman estimated that “ten or twelve old and younge of that countrie” arrived with Pocahontas. A London parish record suggests that one male member died about two months after their arrival in England, for on August 6, 1616, “A Virginian, called Abraham, [was] buried out of Sr. Thomas Smithes.” Another Powhatan apparently lived for several years with George Thorpe, a member of Parliament and sometime councilor to James I, who in 1620 would become Virginia's supervisor of the prospective Indian college; before his departure for that assignment, Thorpe mentioned a document “written [as amanuensis] by the virginian boy of mee George Thorpe.” The youth must have been in England for at least a year, probably much longer, to have mastered English well enough to write a legible copy of a complex text. He is almost surely the “Georgius Thorpe” who was baptized at St. Martin in the Fields on September 10, 1619, and whose burial was recorded seventeen days later as “Georgius Thorp, homo Virginiae.” Another Powhatan who may have come to England and remained past 1617 is Tomocomo's wife and Pocahontas's sister, Matachanna, who could have been caring for the Rolfes' young son Thomas and may herself, like the youngster, have been too ill to return to Tsenacommacah in 1617. Perhaps she returned to Virginia a year or two later; there is no known burial in England, and her very presence in England is conjectural.35

Clear evidence survives that two, perhaps three, female Powhatans remained in England for several years after Pocahontas's death. In May 1620 the Virginia Company noted that “one of the maides w[hi]ch Sr Thomas Dale brought from Virginia…who some times dwelt a servant w[i]th a Mercer in Cheapside is nowe verie weake of a Consumption”; the company paid for her medications.36 Six months later, two young women in the company's care, Mary and Elizabeth (no surnames or Indian names are recorded), were indigent, and Mary—perhaps the unnamed consumptive—was ill. The company tried “to place them in good services where they may learne some trade to live by hereafter,” but such efforts were fruitless, probably because the women lacked appropriate skills or proficiency in English, perhaps because English prejudice curtailed their opportunities. In any case, the company soon cut its losses by sending both maids to Bermuda, where women were in short supply, to be married “with such as shall accept of them.”37

The Virginia Company bore the costs of passage and all necessities for the “two Virginian virgins” and the four boys who served them: clothing, bedding, soap, starch, food, and drink for bodily comfort; bibles and psalters for spiritual comfort. The women carried also the company's request that Governor Nathaniel Butler use “his care and authoritie” to find “honest English husbands” (which Butler thought “a harder task in this place than they wer aware of”) and to arrange for their postnuptial employment: “after some staye in the Ilands,” the company proposed, the Indians “might be transported home to their sauvage parents in Virginia (who wer ther no lese than petie kinges), and so be happely a meanes of their conversion.” John Smith echoed that sentiment a few years later: “After they were converted and had children,” he hoped, “they might be sent to their Countrey [Tsenacommacah] and kindred to civilize them.” The Virginia Company's missionary hopes persevered.38

One of the Powhatan women, probably Mary, died at sea, but the other reached Bermuda and, less than a year later, fulfilled one of the Virginia Company's intentions. In the spring of 1622 she was “married to as fitt and agreeable an husband as the place would afford,” reported Governor Butler, who entertained more than one hundred guests at a lavish reception. Butler's generosity was motivated partly by the hope “that the staungers at their returne to Virginia might find reason to carry a good testimony with them of the wellfare and plenty of this plantation.”39 Although Butler did not identify the strangers from Virginia, the implication is that two or more Powhatans had attended the wedding.

The records are unfortunately silent on what proselytizing efforts Elizabeth (if she was the survivor) may have made in Tsenacommacah or even if she left Bermuda. With the Virginia Colony entering a decade of brutal Indian-English warfare after the Powhatan uprising of March 1622, a Christian Indian and her English husband would have been unlikely immigrants.

Pocahontas in England

Pocahontas was, potentially, Powhatan's most effective envoy to England. True, Tomocomo was Powhatan's designated reporter in the group that accompanied his daughter, and she had not seen her father for nearly four years, yet when Pocahontas reached England in 1616 she could gain entry where Tomocomo could not. Her fluent English, conversion to Christianity, marriage to an Englishman, and adoption of “civilized” clothing made her acceptable to London society (Figure 2.2). And she was a Powhatan princess, welcomed by English nobles and gentry for her high birth as well as her personal charm. With her continuing fondness for her father and her adherence to a vision of Virginia that extended, rather than displaced, her natal society, Pocahontas would probably have shared her observations with Powhatan. The pity is that Tsenacommacah's most effective ambassador to the Court of St. James did not live to tell the paramount chief a word of what she had seen and heard in eight busy months—more useful information about England and the English, probably, than everything gleaned by Namontack, Tomocomo, and the other Virginians who visited England between 1608 and 1617.

Figure 2.2. Pocahontas in 1616: “Matoaka alias Rebecca daughter to the mighty Prince Powhattan Emperor of Virginia,” drawn from life by Simon van de Passe. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University. This engraving—and a copy of it in which Pocahontas's features have been slightly Europeanized—circulated in 1617, and were included in copies of John Smith's Generall Historie (1624).

From the English perspective, Pocahontas was in London primarily to promote the Virginia Company, its missionary program, and the feasibility of English “civility,” even intermarriage, for Tsenacommacah's people. She epitomized England's social aspirations for America. The Virginia Company therefore treated her more prominently and lavishly than it did any of her companions, and to some extent it reaped the expected rewards. Historians and anthropologists have long debated Pocahontas's precise role in England and—especially and most intriguingly—what the experience meant to her, but there is no doubt that from a public relations standpoint, the months before she took ill were unprecedented for an indigenous American visitor.40 Yet despite the far greater attention paid to the Powhatan princess than to any of her predecessors in England, the monopoly of English writings in the surviving sources—although sometimes purporting to quote or paraphrase Indian voices—makes any reconstruction of the events and assessment of their meaning an exercise in cautious probability at best.

This much is documented. While the other members of Dale's delegation were distributed to households throughout London, the Rolfes (and perhaps Tomocomo) lodged initially in an old hostelry and former theatre at the bottom of Ludgate Hill, the Bell Savage Inn (another linguistic irony), owned originally by a family named Savage, though not, apparently, closely related to the Virginia Colony's Thomas Savage.41 There the Powhatan princess received a variety of English visitors and ventured forth to see London's sights and meet its luminaries. The most notable excursions were undoubtedly to attend the royal family. Next in importance, and better recorded, was a visit to Lambeth Palace, across the Thames from Westminster, where the Reverend Dr. John King, Bishop of London, “entertained her with festivall state and pompe,” according to Samuel Purchas, who was also a guest, “beyond what I have seene in his great hospitalitie afforded to other Ladies.” Purchas noted that Pocahontas was patronized by “divers particular persons of Honor, in their hopefull zeale by her to advance Christianitie.” That motive explains the Bishop of London's enthusiasm: his and his successors' clerical jurisdiction—from the founding of Virginia until the Revolution of 1776—included all of English America. If the bishop meant seriously to promote the gospel in the infant British empire, he had best begin with the person John Smith described to Queen Anne as “the first Christian ever of that Nation, the first Virginian ever spake English, or had a childe in mariage by an Englishman.”42 If “that Nation” meant Tsenacommacah, the first and third statements are true; but unless Smith meant fluent English, the second is surely false, in light of Namontack, Matchumps, and other Powhatans who had crossed the Atlantic and must have learned passable English, perhaps with Thomas Hariot's help. But hyperbole aside, Smith's point is sound: Pocahontas was by far the best evidence yet that the colonization of eastern North America might lead to an integrated but predominantly Christian community and a culturally English society. The bishop did his part to honor England's most prestigious religious and social convert.

By the time Pocahontas's triumphal visit neared its completion, the Virginia Company was preparing her next contribution to the conversion of Virginia's natives. On March 19, 1617, the company voted a special award to John Rolfe of one hundred pounds from its missionary funds,

uppon promise made by the said Mr: Rolfe in behalfe of him self and the said Ladye, his wife, that bothe by their godlye and vertuous example in their perticuler persons and famelye, as also by all other good meanes of perswasions and inducemts, they would imploy their best endevours to the winning of that People to the knowledge of God, and embraceing of true religion.43

Armed with this new charge, the Rolfes joined Samuel Argall, Tomocomo, and a perhaps a few more of the Powhatan delegation aboard the George for the arduous voyage home. With Pocahontas's death at Gravesend a few days later, the missionary enterprise lost what Purchas hailed as “the first fruits of Virginian conversion.” Because no other native of Tsenacommacah could match Pocahontas's social stature and achievements, the Virginia Company's interest in bringing other Indians to England waned rapidly, especially when the boys and girls who accompanied Pocahontas failed to fulfill the company's high hopes. In 1622 Sir Edwin Sandys, Sir Thomas Smyth's successor as head of the Virginia Company, discouraged the transportation of more Indians to England for education because “he feared (upon experience of those brought by Sr Tho: Dale)” that the enterprise “might be farr from the Christian worke intended.”44

The failure of Tsenacommacah's boys and girls to absorb English religion and customs did not preclude Powhatan and his successors from sending individual envoys to England, but Tomocomo's experience boded poorly for his category of Indian traveler. At first, Tomocomo had drawn almost as much attention as his sister-in-law, although for antithetical reasons. Whereas Pocahontas was substantially anglicized and therefore admired in England for what she had become, Tomocomo was blatantly and proudly Indian, shunning English religion, English clothing, even English hair styles. Although the sources are not specific on the garb he affected in London, it was probably little more than a breech clout, mantle, and moccasins; and, as we know from Samuel Purchas, the right side of Tomocomo's head was shaved clean while the left side sported a “Devill-lock” several feet long.45 Tomocomo was a powerful, dramatic presence.

Smith, who had known Tomocomo in Virginia, encountered him again in London in early 1617. Smith thought the meeting was “by chance,” but Tomocomo insisted that Powhatan had ordered him to find Smith, who was “to shew him our God, the King, Queene, and Prince, I [Smith] so much had told them of.” Smith's response was brief and unsatisfactory to Tomocomo: “Concerning God, I told him the best I could, the King I heard he had seene, and the rest hee should see when he would”—that is, whenever Tomocomo wanted to. But Tomocomo refused to believe he had seen King James until Smith (who had surely heard of their attendance at a royal masque) explained the circumstances. “Then he replyed very sadly,” Smith recalled, “You gave Powhatan a white Dog, which Powhatan fed as himselfe, but your King gave me nothing, and I am better than your white Dog.”46

If Tomocomo barely recognized King James, he surely got to know Samuel Purchas, B.D., pastor of St. Martin's by Ludgate, who tried to enlighten Powhatan's envoy about Anglican Christianity, with an unnamed employee of Sir Thomas Dale as interpreter—perhaps an Indian, more likely Thomas Savage or another bilingual colonist. “With this Savage,” Purchas recalled of Tomocomo, “I have often conversed at my good friends Master Doctor Goldstone [Theodore Gulstone], where he was a frequent guest.” Purchas's description of those conversations is brief but intriguing. They were not, as one might expect, didactic monologues by Purchas and Gulstone on Anglican theology and English culture; rather, Tomocomo did his share of showing and telling. “I have both seen him sing and dance his diabolicall measures,” Purchas observed, “and heard him discourse of his Countrey and Religion.” On the latter subject, Purchas had only disdain for the Indian's views. Tomocomo, he concluded, was “a blasphmer of what he knew not, and preferring his God to ours, because he [i.e., the Powhatans' god] taught them (by his owne so appearing) to weare their Devill-lock at the left eare.” Tomocomo, Purchas protested, “beleeved that this Okee or Devil had taught them their husbandry, etc.”47

While Tomocomo was unpersuaded by England's theology, he had to be impressed by its population, which numbered two to three million compared to Tsenacommacah's ten to fifteen thousand. Powhatan had asked him “to see and signifie the truth of the multitudes,” and Tomocomo dutifully notched the numbers on a stick en route from Plymouth to London, “But his arithmetike soone failed.” Purchas reported that Tomocomo was “no lesse amaze[d]…at the sight of so much Corne and Trees…, the Virginians imagining that defect thereof” in England had caused the migration to America.48 Like other Indian visitors to England before him, Tomocomo must have told a disappointed Powhatan that the English, despite their many shortcomings by Indian standards, were numerous beyond belief and that their natural resources exceeded Tsenacommacah's. It was a grim message for Indian leaders who expected England to be as sparse and inept as its early American outposts suggested.

Partly, perhaps, because Tomocomo was disturbed by England's boundless population and potential power, but more likely because he felt slighted by King James and patronized by the Reverend Purchas, Powhatan's envoy carried home a jaundiced view of his hosts. Upon his return to Tsenacommacah in May 1617, he lambasted the whole nation. “Tomakin rails agt Engld[,] English people and particularly his best friend Tho: Dale,” Governor Samuel Argall observed, though he added that “all his reports are disproved before opachanko [Opechancanough] & his Great men” to the end that “Tomakin is disgraced.”49 Unless Argall indulged in wishful thinking, it appears that some of Tomocomo's well-traveled compatriots—possibly Matchumps, Kainta, or members of the Pocahontas party—contradicted his stories.50 Tomocomo would be Tsenacommacah's last envoy to England.

The Failure of Diplomacy

During nearly two decades of Powhatan visits to England, thousands of English men, women, and children gawked at the strangers from across the ocean. By and large, English viewers paid dutiful attention to Lady Rebecca Rolfe for her social standing and the royal family's imprimatur and especially for her embrace of Protestant Christianity, the English language, and English customs; she was, in Purchas's words, “accordingly respected.” Londoners stared in awe, very likely, at Namontack, Kainta, and Tomocomo, who had high status at home and were surely escorted by officials of the Virginia Company, themselves men of some prominence. But English treatment of the boys and girls who lived in private homes, walked London's streets, and struggled with the Anglican catechism and the Jacobean classical curriculum was probably insensitive, perhaps callous, even malicious, which might account for the Powhatan children's failure to impress Edwin Sandys. In some instances, natives of Tsenacommacah may have followed the footsteps of the captives of 1603 as sights to be ogled or, like Martha's Vineyard's Epenow a decade later, be “shewed up and downe London for money as a wonder.”51

Which is not to say that England learned nothing from the visitors. Assuming that the twenty or more Indians from Tsenacommacah were representative of their tribesmen in physique and physiognomy, the English public saw people quite similar to themselves in size and general appearance, not the monsters or sharp-toothed cannibals of many fanciful reports from the New World. The English public also learned that the Indians' dark color was largely a veneer. Reverend William Crashaw's sermon of early 1609 explained that “a Virginean, that was with us here in England [probably Namontack],…was little more blacke or tawnie,” after wearing English clothes for awhile, “then one of ours would be if he should goe naked in the South of England.”52 Virginians, English observers must have concluded, were eminently suitable to “civility,” for despite Tomocomo's alarming costume and immense pony tail, Pocahontas—and most if not all other Indians in England—appeared regularly in adopted English attire and accepted, superficially at least, English norms of behavior. And along with the living examples of native America before their eyes, English readers had corroborating testimony in the descriptive accounts of Indians and their cultures, sometimes partly about the Indians in England, by a host of English writers: John Smith, Samuel Purchas, James Rosier, John Brereton, Ferdinando Gorges, and many, many more, and numerous illustrations, original or derivative, by John White, Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, the de Bry family, and others. The English people did not become fully informed about American natives by such publications nor by the Indians' physical presence, of course, but many Londoners surely became less ignorant, possibly less prejudiced, by learning how truly human they were. Crashaw insisted, “the same God made them as well as us, of as good matter as he made us, gave them as perfect and good soules and bodies as to us and the same Mesiah & saviour is sent to them.” Indians, in short, are “our brethren.”53

Crashaw was speaking, of course, as a clergyman. For England's secular proponents of American colonization, visiting Indians, whether they came willingly or not, had other uses. Except for some passages in the writings of Purchas and Smith, few accounts survive of how information about America was gleaned from the Powhatans, but evidence exists on how Englishmen during the same era probed other Indian visitors' minds. James Rosier, who described five Abenakis brought from coastal Maine in 1605 is a prime example; he had many conversations, by sign language and rudimentary spoken words, in which he learned much geographic and ethnographic knowledge about coastal Maine. For the Indians, ironically, such conversations often backfired. Of the three Abenakis who lodged in his home, Sir Ferdinando Gorges remembered, “the longer I conversed with them, the better hope they gave me of those parts where they did inhabit, as proper for our uses, especially when I found what goodly Rivers, stately Islands, and safe harbours those parts abounded with.”54 The Abenaki homeland would soon suffer from English incursions and imported diseases.

Indians from Maine, Virginia, or elsewhere also gleaned information about England, and every visitor who survived his stay abroad no doubt carried home an abundance of useful observations. The difference between Indian and English intelligence-gathering was in its purpose: imperial, in England's case; protective, in the Indians'. Although England's vision of an American empire was still in the future, the movement for colonies and converts was gaining momentum, stimulated in part by the presence of Indians in England.

Powhatan contributed to the flow of visitors by sending Namontack in 1608, John Smith reported, “to know our strength and Countries condition.” Namontack probably acquired a general sense of both matters—England's military “strength” as represented by castles and cannons, uniformed men and armed ships; England's “condition” as reflected in swarming people and bustling commerce, as well as undercurrents of economic, religious, and political unrest. Namontack's “true report” to Powhatan must have made the chief more suspicious of English intentions and more skeptical about cordial cohabitation in the Virginia tidewater. Eight years later, Powhatan's charge to Tomocomo was essentially the same as to Namontack: find the truth and report it faithfully to me. In the interval between the first and last envoys, “some others which had been heere in former times,” Purchas noted in 1617, citing Thomas Dale as his source, “being more silly, which having seene little else then this Citie [London], have reported much of the Houses, and Men, but thought we had small store of Corne or Trees.”55 Such selective reporting may explain why Tomocomo tried to record the population on a stick.

The disquieting facts collected by Powhatan's envoys surely impressed and discouraged the chief and his successors—his brother Opitchapam briefly, then their brother Opechancanough—for many years. England had too many emigrants lusting for land, too many ocean-going vessels designed for commerce or war, too many firearms, and too many idle soldiers ready for new mayhem. By 1617, when Tomocomo returned to Tsenacommacah, the colony's booming tobacco crops had created insatiable demands for more farm land, with devastating effects on tribal holdings and on Anglo-Indian relations. By then, Powhatan had perhaps grasped the full import of England's restless population and perceived the colony's determination to wrest Tsenacommacah from Indian control. Had he fully comprehended that dismal prospect a few years earlier, he might have rephrased his lament of 1614 to Ralph Hamor. “I am now olde,” he told Hamor, “and would gladly end my daies in peace, so as if the English offer me injury, my country is large enough, I will remove my selfe farther from you.”56 Although peace prevailed when Powhatan died in July 1618, it would last fewer than four more years. By hindsight, it seems clear that the death of his favorite daughter and Tsenacommacah's most eminent envoy to England had already undermined the prospects—if they ever seriously existed—for a truly bicultural society on the American side of the seventeenth century's Atlantic world.