In our day to day work, my colleagues and I see time and time again poor decisions made by management based on mistakes held to be true in financial models. Companies are loathe to pay for specialists to come in and check their models, seemingly happier to pay a greater price through lost sales, higher costs and reduced market share instead. It is important to understand why a self-review or an audit is so cost-effective and necessary.

I am going to go over this again. It needs emphasising. Spreadsheeting is often seen as a core skill for accountants, many of whom are reasonably conversant with Excel. However, many would-be modellers frequently forget that the key customers of a spreadsheet model (i.e. the decision makers) are not necessarily sophisticated Excel users and often only see the final output on a printed page, e.g. as an appendix to a Word document or as part of a set of PowerPoint slides.

With this borne in mind, it becomes easier to understand why there have been numerous high profile examples of material spreadsheet errors. I am not saying that well-structured models will ensure no mistakes, but in theory it should reduce both the number and the magnitude of these errors.

Modellers should strive to build “Best Practice” models. Here, we want to avoid the semantics of what constitutes ‘best” in “Best Practice”. There is no set of rules that is applicable for each and every situation. A quick scan of the web will find you various rules such as Best Practice Spreadsheet Modelling Standards, FAST, SMART and TransparencEY amongst others. Each requires modellers to read a large set of rules to learn by heart. Who does this? When was the last time you read documentation or instructions? Instead, let me revisit one final time to consider the term as a proper noun and reflect upon the idea that a good model has four key attributes (CRaFT):

•Consistency: Formulae should be copied uniformly across ranges, to make it easy to add / remove periods or categories as necessary. Sheet titles and hyperlinks should be consistently positioned to aid navigation and provide details about the content and purpose of the particular worksheet. For forecast spreadsheets incorporating dates, the dates should be consistently positioned (i.e. first period should always be in one particular column), the number of periods should be consistent where possible and the periodicity should be uniform (the model should endeavour to show all sheets monthly or quarterly, etc.). If periodicities must change, they should be in clearly delineated sections of the model.

•Robustness: Models should be materially free from error, mathematically accurate and readily auditable. Key output sheets should ensure that error messages such as #DIV/0!, #VALUE!, #REF! etc. cannot occur (ideally, these error messages should not occur anywhere).

•Flexibility: When building a model, the user should consider what inputs should be variable and how they should be able to vary. This may force the model builder to consider how assumptions should be entered.

•Transparency: Most Excel users are familiar with keeping inputs / assumptions away from calculations away from outputs. However, this concept can be extended: if most decision makers see models printed out or on slides, the spreadsheets should be understandable without sight of the formula bar.

If your model adheres to these four standards, you are most likely in possession of a “Best Practice” model.

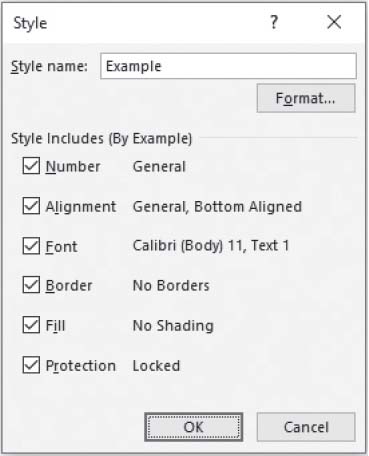

One way to make your spreadsheets appear more consistent is to employ styles in your models. The terms ‘format’ and ‘style’ are often used interchangeably but they are not the same thing. To see this, select any cell in Excel and apply the shortcut keystroke CTRL + 1. This shortcut brings up the Format Cells dialog box:

Excel has six format properties: Number, Alignment, Font, Border, Patterns and Protection. A style is simply a pre-defined set of these various formats. With a little forethought, these styles can be set up and applied to a worksheet cell or range very easily.

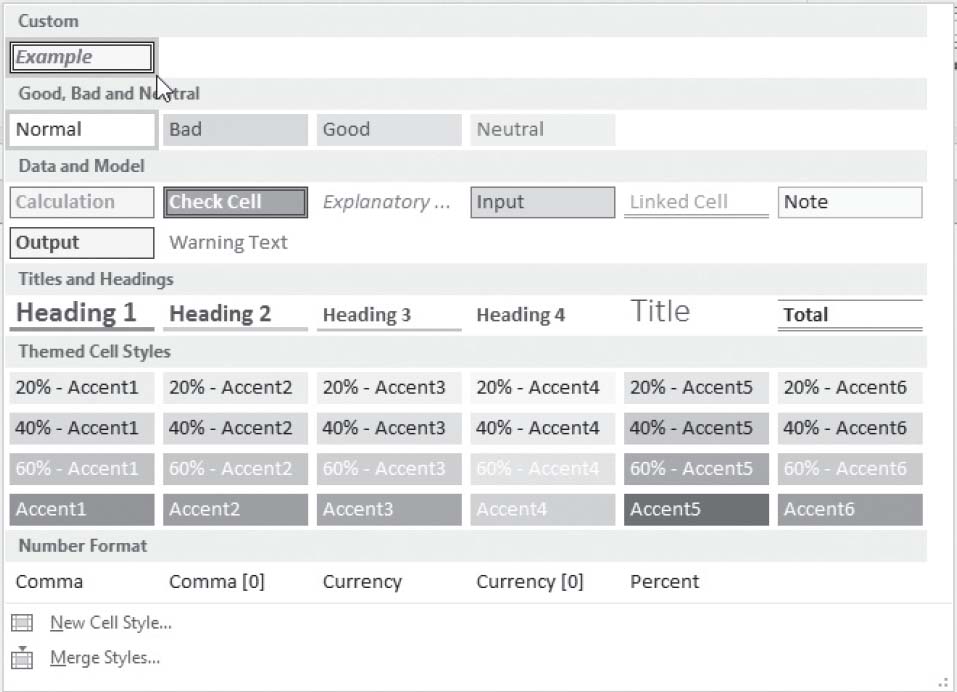

In all versions of Excel, styles may be accessed via the keyboard shortcut ALT + O + S:

Depending upon your version of Excel, the dialog box may look slightly different to the image above. The dropdown box (highlighted above) can be edited so that new styles may be created. If you click the ‘Modify’ button (Excel 2003 and earlier) or the ‘Format’ button (Excel 2007 and later) the ‘Format Cells’ dialog box appear again and formats may be created in the usual way, clicking on ‘OK’ or ‘Add’ to complete the process.

Now that this style has been added, in Excel 2007 and later you simply select the range and then click on the style in the Styles gallery on the Home tab:

The difference between Formats and Styles becomes obvious when you realise you want to change (update) a style. Just select one of the cells that the style is attached to and call up the Style dialog box in the usual way, modifying the style as required. Click ‘OK’ when finished. Note that every cell in the open workbook that uses this style has automatically updated.

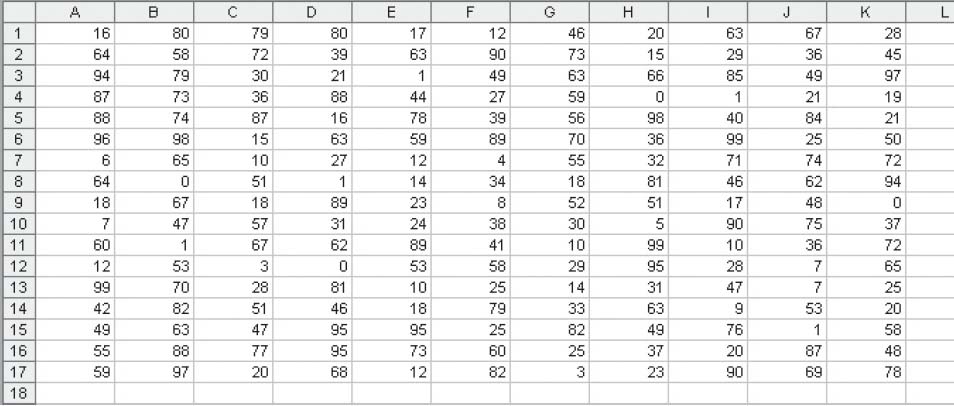

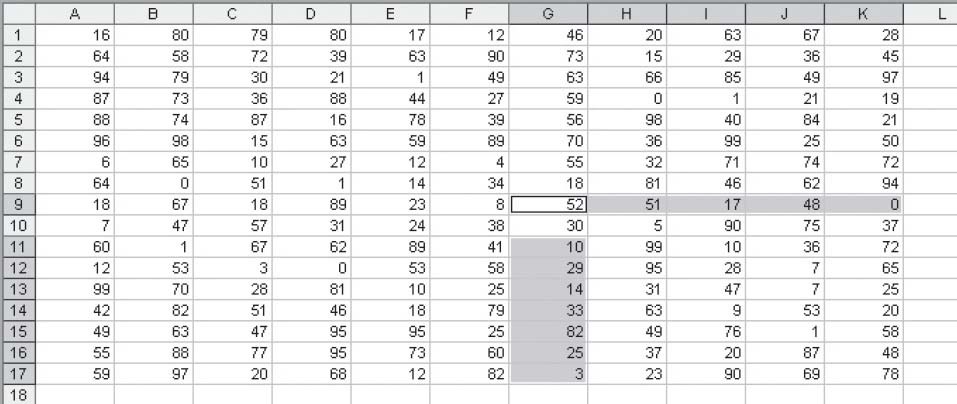

Consider the following block of data:

Let’s assume this data is supposed to refer to a similar block of data elsewhere. How can we tell if the formula has been copied across and down correctly? Inspection by eye achieves nothing here.

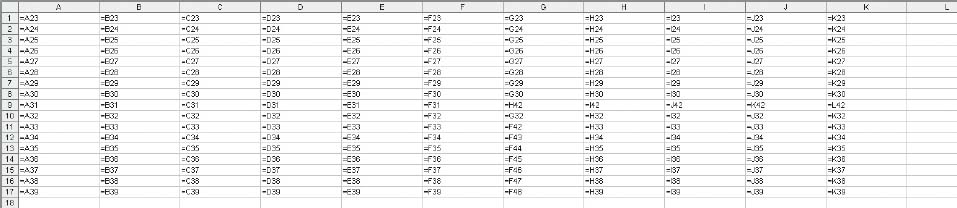

One option is to use the keyboard shortcut CTRL + (the character is the key to the left of the 1 on a standard QWERTY keyboard):

This shortcut toggles cell values with their content (i.e. formulae). This will show formulae which have not been copied across properly, but this is still fraught with user error (can you spot the relevant cells?) and would be cumbersome with vast arrays of data.

Instead, there is a simpler, automatic approach. Select all of the data (click anywhere in the range and press CTRL + *). Then use the keyboard shortcut CTRL + \ viz.

This automatically selects all of the cells whose contents are different from the comparison cell in each row (for each row, the comparison cell is in the same column as the active cell).

CTRL + SHIFT + \ selects all cells whose contents are different from the comparison cell in each column (for each column, the comparison cell is in the same row as the active cell). In this example, where a formula is supposed to be copied across and down, there will be no difference.

These cells can now be highlighted and reviewed at leisure.

Whilst nothing replaces the peace of mind in obtaining a third party model audit (see later), I often get asked to provide an initial list of checks model builders can perform on their own models. Assuming modellers do not have access to specialist auditing software, this list is not intended to be exhaustive (I can’t give away all of my secrets!), but it’s a good starting point:

1.Use Excel’s Background Error Checking - Strictly speaking, this should be instigated during the model development phase as it can assist the modeller throughout construction.

To enable this functionality, go to Excel’s Options (ALT + T + O) and in the ‘Formulas’ section, ensure that the ‘Enable background error checking’ tick box is checked. Once activated, the user can select which error checking rules should be catered for by inspecting the ‘Error checking rules’ section directly beneath this check box.

This functionality does not prevent errors from occurring, but potentially erroneous cells are highlighted by Excel in a fashion similar to cells that include comments, viz.

The problem with this approach is it is easy to miss this annotation, but it is better than nothing.

2.Use Excel’s Formula Auditing tools - In the ‘Formulas’ tab of the Ribbon, use the tools in the ‘Formula Auditing’ section of the toolbar. In particular, ‘Error Checking’ is useful (although it may only be applied to one worksheet at a time) as it highlights a lot of issues Excel is programmed to consider as “dubious” (e.g. inconsistent formulae, #DIV/0! errors).

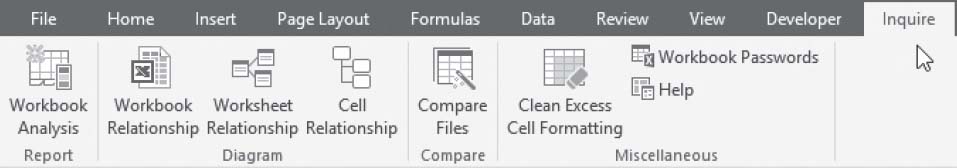

For those lucky enough to have the Professional Plus version of Excel 2013 or later, Spreadsheet Inquire adds to Excel’s in-built functionalities to allow users to analyse the links between workbooks, worksheets and / or individual cells:

3.Find Prima Facie Errors - There are glitches in Excel and occasionally, a prima facie error may slip through. These obvious errors are particularly embarrassing to miss, as these are usually identified by end users picoseconds after a model has been handed over.

There is a simple sure-fire check: CTRL + F (Excel’s ‘Find’ functionality).

Simply type ‘#’ in ‘Find what’ (the obvious errors all begin with ‘#’), but then click on the ‘Options’ button to display the options and change the ‘Within’ setting to ‘Workbook” and then look at ‘Formulas’, ‘Values’ and ‘Comments’ in turn using the ‘Find All’ button to correct any issues identified.

4.Review inconsistencies in formulae - as discussed earlier.

5.Look for errors in unintentional links in range names - The Name Manager in Excel (CTRL + F3) can be used to both identify links and range names containing errors.

6.Locate unintentional links - How often does the following dialog box send shivers down your spine?

So-called “phantom links” (i.e. links that seem to appear from nowhere) should be located and eradicated.

7.Perform high level analysis - Depending upon the purpose and scope of the model built, you can create a check list of items to review for each model (e.g. does your Balance Sheet balance? Does the cash in the Cash Flow Statement reconcile to the amount in the Balance Sheet? What is the forecast days receivable?). Using accounting ratios focusing on profitability, liquidity and gearing may be beneficial too. More of that in the next - and final - chapter.

8.Create “quick” charts - For key outputs, you can graph the data momentarily. Simply highlight the data and press the F11 function key, viz.

Do the charts make sense? Are there unseemly ‘blips’ or inconsistent trends? Can dramatic changes be readily explained? These rough and ready charts can highlight calculation mistakes in an instant on occasion.

9.Close and re-open - Do you get unexpected error messages upon opening? This is a frequent oversight made by modellers. Are calculations set to ‘Automatic’? Are there any unexpected links, circular arguments or other error messages (e.g. “Not enough memory to display”)? It is better that you discover these issues before your customers do.

10.Spell check - Nothing looks less professional than opening a Dashboard Summary to look at the “Selas Turnover” or items labelled incorrectly. There is really no excuse for not spell checking a model (‘Review’ tab of the Ribbon has a spelling check or simply hit ‘F7’).

11.Printing and viewing - Not strictly speaking an error, how many times have you decided to print out a model sent to you only to find it print over several reams of paper that even Tolstoy would have been proud of? It is worth taking time to set up print margins and included headers and footers. Also, each page should be reset (CTRL + HOME) and saved on the front page so that models are not opened with the end user finding themselves in cell GG494 of a sheet called “ID_Rev_MR”. Been there, done that, bought the consequences.

12.Protection - If as a modeller you have invested sleepless nights in getting a model to work, you do not really want an end user typing “17” over a sophisticated formula that has taken hours to get precisely right. These unowned hard codes often come back to haunt the modeller - unfairly - and cast doubt over the credibility of an otherwise robust model. Take the time to protect cells, worksheets and the workbook as required to avoid these issues.

A self-review is a cheap way of checking a model. Sometimes you need more than that. There are professional model audit firms out there that specialise in reviewing models (such as ourselves - quick advertising plug). They will incorporate a rigorous analysis of a model incorporating one or both of the following processes:

•Line-by-line (detailed) review; and

•Analytical (high level) review.

The line-by-line review tests each unique formula in the model to be checked using specialist model auditing software such as Spreadsheet Advantage, Spreadsheet Detective or Spreadsheet Professional in the base case scenario. Other scenarios may be reviewed depending upon the scope of the work. After careful analysis, auditors will provide recipients with a report, called the Model Review Findings, detailing any errors identified. These Model Review Findings will be categorised as to severity. We using the following definitions:

•Category 1: Affects the calculations in versions of the model within the scope of the review;

•Category 2: May affect the calculations under assumptions outside the scope of the current review;

•Category 3: Unclear or bad practice. This may affect the user’s interpretation of the results, but does not necessarily affect the calculations; and

•Queries: Questions asked to increase understanding of the calculations with the express intention of identifying errors.

Before a final report can be provided, all Queries and Category 1 issues have to be resolved. Category 2 and 3 issues do not necessarily have to be corrected for the review, but may represent a risk to model users under other scenarios.

Once these errors have been corrected, if applicable, the audit will undertake a high-level analytical review of the model and its key outputs. Once completed, usually the model auditors will provide a report describing whether:

•The calculations in the model are in all material respects internally consistent and mathematically correct, with respect to whatever scope was agreed; and

•The model allows agreed selected changes in assumptions to correctly flow through to the results.

Given a model audit is a highly formal review made by a third party, auditing firms will generally not be responsible for performing any of the following tasks:

•Commenting on the completeness or reasonableness of the assumptions, including accounting, tax and regulatory-related assumptions;

•Commenting on the probability of the projections being achieved;

•Considering the cash flows or other balances from the perspective of specific shareholders and lenders, other than to the extent that they are explicitly represented in the model;

•Reviewing links to files outside the model;

•Assessing whether the financial statements are presented in a format suitable for public financial or tax reporting;

•Reviewing commentary embedded within cell notes; and

•Commenting on the model’s compliance with generally accepted accounting principles or tax legislation.

This is often an expensive exercise, but when business decisions will prove very costly if model outputs are wrong, this is often a better option when much is riding on the logic of the model. Audits do not usually comment on the assumptions. I would recommend undertaking a self-review first before submitting a model to a formal audit. It saves time and money and leads to a more collaborative exercise.