9

Ile Sainte Hélène

The next morning dawned to a completely changed atmosphere in the camp. As we woke up and cautiously poked our faces out of the dormitories, no military presence was to be seen, and soon the compound was full of men taking in the details of our new accommodation.

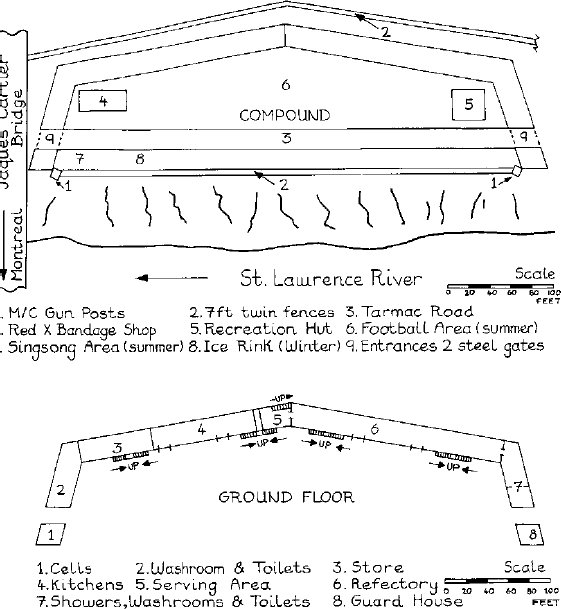

A long three-sided building of three floors, surmounted by a gently sloping roof, the structure was made of stone blocks about two feet thick. Access to the ground floor was by means of two large doors in the centre section, whilst the upper floors could be reached both by internal wooden stairs and from the outside by means of sets of stone steps leading directly up from the compound. The floors of the upper sections were of rough wood, and the ground floor was paved with large flagstones. The rear of the fortress was an unbroken stone wall and at the front of the building, regularly spaced window apertures gave light and ventilation.

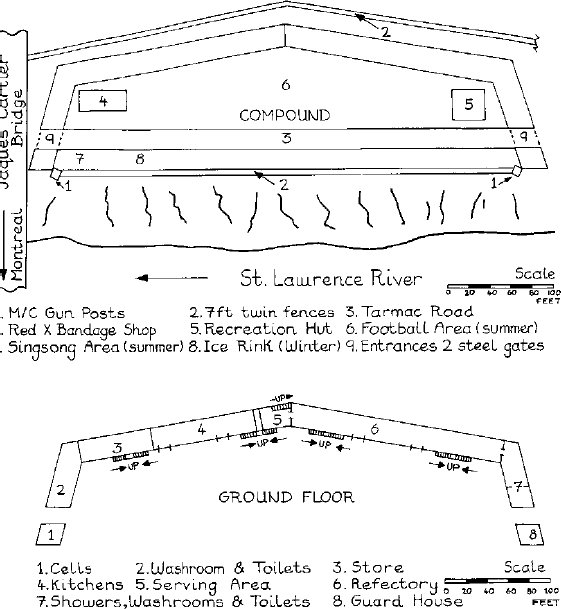

Across the front of the building a seven-foot-high, double barbed-wire fence had been erected to form a courtyard about 100ft wide by 350ft long. At either end of the fence stood an elevated wooden tower, each equipped with a heavy machine-gun manned by three soldiers. The whole structure ran parallel to the river, separated from it by some 50 yards of gently sloping ground. Across the river lay the city of Montreal, surmounted by a huge neon illuminated crucifix on the heights of Mount Royal beyond. Dominating the scene was the impressive structure of the Jacques Cartier bridge as it passed over the northern end of the building, with one of its giant concrete pylons almost touching the perimeter fence of the compound. The old fortress of Ste Hélène, built so many years ago by Champlain on the island named after his young bride, was now serving as an internment camp for 407 Italian prisoners.

News of the arrival of the prisoners had evidently filtered through to the population of Montreal, for the bridge was thronged with curiosity seekers strolling along the walkway, stopping whenever possible to stare at the packed compound below them. Soldiers posted on the bridge kept the pedestrians on the move. These soldiers, together with the machine-gun crews on the towers, were the only military personnel in sight.

The men had now donned the clothes given to them the night before, which consisted of a blue shirt with a large red circle on the back, trousers with a broad red stripe running down the side of the leg, and a blue jacket, also with a large red circle on the back. As the morning wore on without any sign of guards appearing inside the compound, the men gained confidence, and soon the courtyard was packed with a milling mass of blue-clad prisoners. Although the space available was very limited, after the claustrophobia of the Ettrick the men revelled in the luxury of freedom of movement, and strolled around exchanging experiences of the night before, comparing cuts and bruises.

After some time the gates of the camp swung open to signal the entrance of a group of soldiers. The officer who interrogated Ralph Taglione the night before, stepped forward and began to address us from the top of the stone steps set into the wall of the fortress. With a slight Irish intonation to his voice, he introduced himself as Major O’Donohoe, the Camp Commandant, and with no reference to the events of the night before, informed us that this was to be our permanent camp. He then presented to us Captain Pitblado, who was to instruct us in the routine of the camp.

The captain was a jolly looking, rotund little man approaching middle age, with the face and manner of an avuncular WC Fields. He smiled broadly, waved a hand as if in greeting, then proceeded to address the assembled prisoners in the manner of a boy scout leader exhorting his adolescent charges.

This was to be our home for the foreseeable future, he said, so everyone had to cooperate to make it comfortable for all. Each group of 20 had now to choose a leader, who in turn would elect a Camp Leader, who would be in daily contact with the military to ensure the smooth running of the camp. Provisions would now be arriving, and the first task of the prisoners would be the selection of their own kitchen personnel. He beamed cheerfully at us and gave a little wave with a plump hand. He then concluded his address with a little homily by which he was to be forever remembered, and which was to become the catch phrase of the camp.

‘Now lads, now that we know one another we’ve got to play ball together. You play ball with me and I’ll play ball with you’.

At this, there were a number of understandable sotto voce comments from the prisoners, still nursing the bruises of the night before. Then, flanked by two massively built sergeants, Le Seour and Rutherford, the former of whom had been noticed acting with great enthusiasm and vigour at the reception of the previous night, the little captain began a tour of the compound. He nodded pleasantly to all and sundry; his manner that of a paternal schoolmaster making himself acquainted with his pupils. He stopped from time to time to speak to individual prisoners, always finishing the conversation with his catchphrase. . . ‘You play ball with me and I’ll play ball with you’.

Nevertheless, Pitblado’s manner and walkabout amongst the prisoners served the purpose of creating a much more relaxed and less fearful atmosphere in the camp. Moreover the promise of the arrival of provisions and the prospect of good and regular meals boosted morale, pushing into the background the memory of the brutalities of the previous night. Captain Vinden then made an appearance at the top of the steps. He had spoken no more than a few words when the men showed one of the very few examples of solidarity in the face of their captors. A low and sustained sound of booing arose from the compound and the prisoners retreated into the interior of the building, leaving the captain to direct his words to an empty courtyard. There was no questioning the unanimity of feeling as to the captain’s role, or lack of it, in the previous night’s proceedings. After a few more weeks of occasional appearances in the camp he was never seen again.

The first few days in the camp passed in a flurry of organisational activity. We were such a disparate group of individuals from so many different backgrounds that the organisation of the camp was not an easy matter. We did not even share a common language. A good 20 per cent of the men spoke only English, and many of the sailors spoke only their own dialects. Apart from the sailors none of us had ever been subjected to any form of group discipline. It has been said that in any group of four Italians you will find five different opinions on any given subject. The proof of such an observation could be found in the behaviour of the Camp S inmates in the simple matter of choosing group leaders for themselves. No people on earth have been as well conditioned by experience and history to be suspicious and cynical of those placed in authority over them as the Italians, and this dislike of authority is often transformed into lack of cooperation and civil disobedience.

Therefore the act of picking one person from a group of 20 strangers to be their representative became a labour of monumental proportions. Many, ever suspicious of motives, changed their minds from one moment to another; for to put power, however little, into the hands of an individual until one could be sure of that person’s patronage, became a matter of the utmost importance.

Amongst the merchant seamen these matters were quickly resolved, for they already had a chain of command which they continued to adhere to. In some of the groups the background of origins was so similar, as in ours, for example, where all the prisoners came mainly from a Scottish environment, that the selection of a leader was not a matter of great argument. In some of the other groups however, the problem was not so easily resolved.

Not only did the members of these groups come from a great variety of social backgrounds, but it has to be remembered that Italy at that time had become a nation only a few decades before. Despite Mussolini’s furious efforts to instil a sense of nationhood, there remained a vast and almost unbridgeable gulf between the northern and southern regions of the country. There was, and to some extent there is still to this day, a great division between the cultural and psychological background of a Milanese or a Tuscan, and that of a Calabrian or a Sicilian. Add to this quasi racial difference the political elements in the camp, with Fascists, Communists and Liberals scattered throughout, and one had a perfect recipe for disorder.

In time, however, the question of group leaders and then of camp leadership was settled. The function of the Camp Leader was to liaise with the military authorities and for this role Tino Moramarco was chosen. He was a tall and handsome figure of a man, about six foot tall, of magnificent physique, and had formed part of the Italian decathlon team in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, although without any great success. His present occupation was obscure. The unkind ones in the camp said that he was nothing but a gigolo, but whatever his occupation, he cut an imposing figure at the head of the camp. Since he was not possessed of any great intellect and did as he was told by his companions, he was reckoned to be just right for the job.

The first item to be sorted out was the staffing of the kitchen. To Captain Vinden’s description of two Italian attributes, recently enunciated by him on the Ettrick, another could definitely be added — a love of good food. Among the prisoners were some of London’s finest chefs and since the kitchen provisions were of first-class quality, we were eventually able to experience meals the equal of which would have been difficult to find in any of the best restaurants of Montreal.

We settled down to make the best of our circumstances. As a permanent dwelling place Camp S left a lot to be desired. Sleeping quarters were cramped and lavatory accommodation was inadequate, which led to long queues in the morning. Recreational facilities were non-existent, and the compound was far too small to accommodate 400 men at any one time.

On the plus side the food was good, and the military presence was at a minimum, although we could always see the two machine-gun towers overlooking us as we walked about in the compound. Our view across the river was spectacular, with the bridge and the magnificent vista of the city. The benefit of the view was two-edged, however, for as time passed, and with no end to our captivity in sight, the presence of the city such a short distance away served only to increase our longing for freedom. But such emotions had not as yet had time to formulate. Very few in the camp believed that our imprisonment would last for any great length of time, and so at the beginning all our energies were directed to adjusting to our new circumstances.

Camp routine was soon established. Reveille was at 7am, when the blowing of a bugle heralded the arrival of a platoon of soldiers, who stood rigidly to attention as the Union Jack was run up a flagpole in the centre of the yard. Under threat of being shot at, no prisoner was allowed into the compound before that time, but by then many of the men would be up and about inside the building, going down through the refectory into the toilet area, hoping to attend to their needs before the main body of the camp awoke. Breakfast was at 8am when we lined up at the kitchen for morning coffee and bread. Then the work parties, whose composition had already been posted up in two languages on the notice board, would begin the job of cleaning up the refectory and preparing the camp for morning roll-call and inspection.

A camp office had been set up from which the daily orders were issued, and because of my fluency in both languages and the contacts I had already established in the various factions in the camp, I was offered a job there by Moramarco. I seemed to have a natural aptitude for languages, was well on my way to understanding the various dialects of the sailors, and I found the work there very satisfying.

The cleaning and disinfecting of the latrines was a most unpleasant task, and the one to be avoided most if at all possible. After a morning’s use by 400 men, the 15 loos would be well-choked and the cleaning of them was a Herculean task. This work was apportioned daily on a rota basis to each group, and the only ones excused from it were the priests, the ships officers, the Camp Leader and his office workers, the 20 or so elderly of the camp and anyone with a doctor’s line for exemption. A small room at the side of the dormitories had been designated as a sick room, with Dr Rybekil, a Jewish refugee, in charge, who was kept extremely busy with applications for daily work exemptions.

By 11am the dormitories, kitchen, refectory and toilets would be clean and in order. Roll call would then take place in the compound, where we stood scruffily to attention as we were inspected by the major and counted by a sergeant. A deferential Moramarco would follow at the major’s heels taking note of his many complaints, for the civilians were an untidy lot who did not conform to the standards of neatness expected by the Camp Commandant. With the roll-call over, work would start in the kitchen for the lunchtime meal which was served around 1pm.

After these activities the boredom of the day continued. The prisoners congregated in little clannish groups, sauntering idly around the compound. Groups of opposing views would be studiously avoided, and conversation would endlessly be centred around the progress of the war and the possible duration of their captivity. With the long hot afternoon over, there came a summons to the evening meal, another roll-call in the compound, then lights out and bed.