One

IN THE BEGINNING

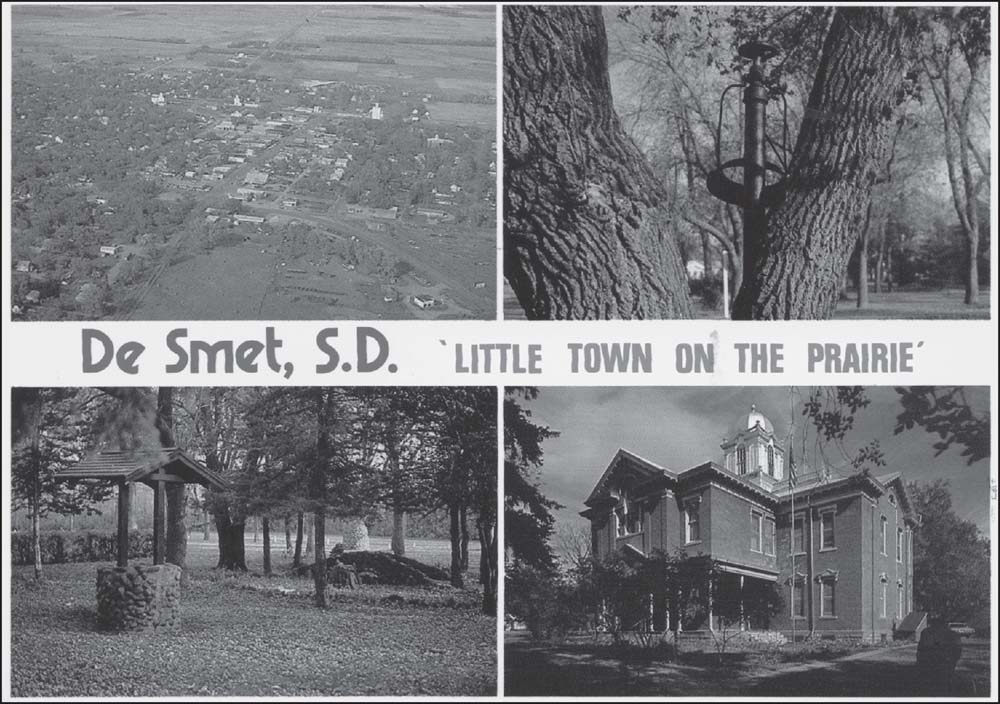

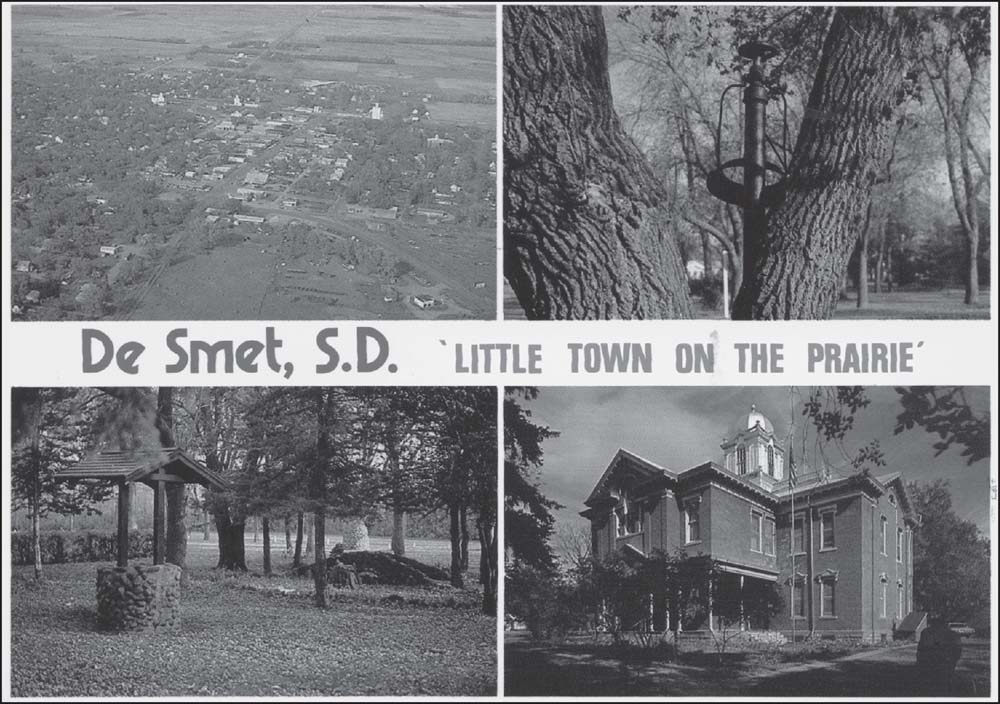

Families in covered wagons rolled into Dakota Territory as the West expanded. Railroads were being built, and it was not long before they steamed and whistled into De Smet. De Smet, the “Little Town on the Prairie,” has stretched its borders in all directions and has seen people arrive from all over the world.

Only stakes in the prairie grass indicated the site for the town of De Smet in early 1880. As the Chicago and North Western Railway extended its Dakota Central branch from Tracy, Minnesota, to Pierre, South Dakota, on the Missouri River, it established small towns along the way, including De Smet. The stakes in the ground soon became a bustling little community.

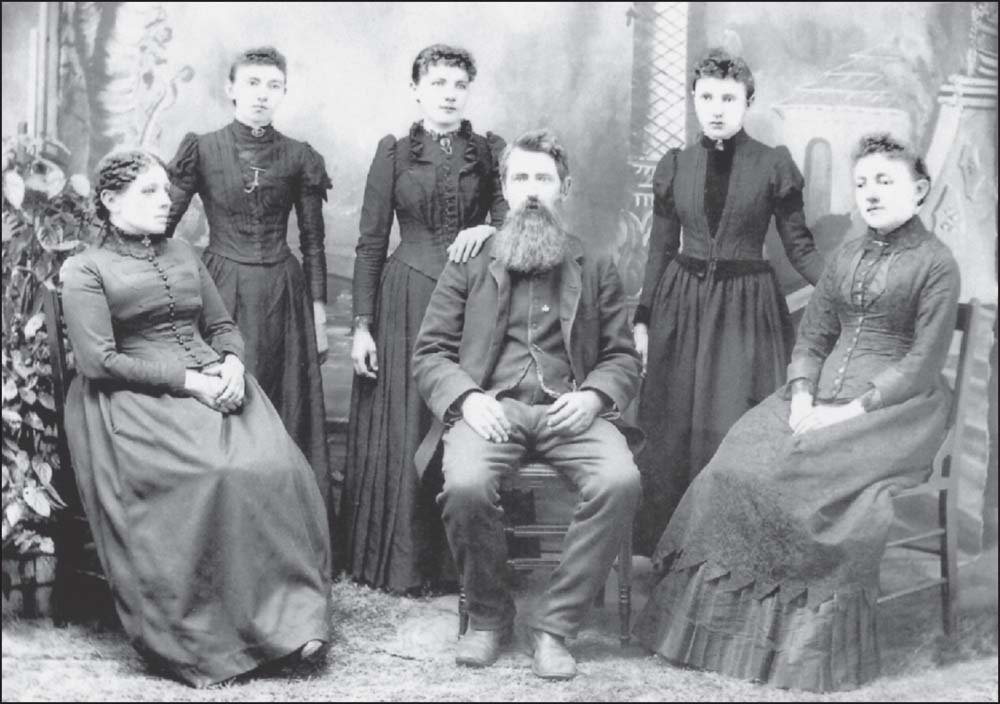

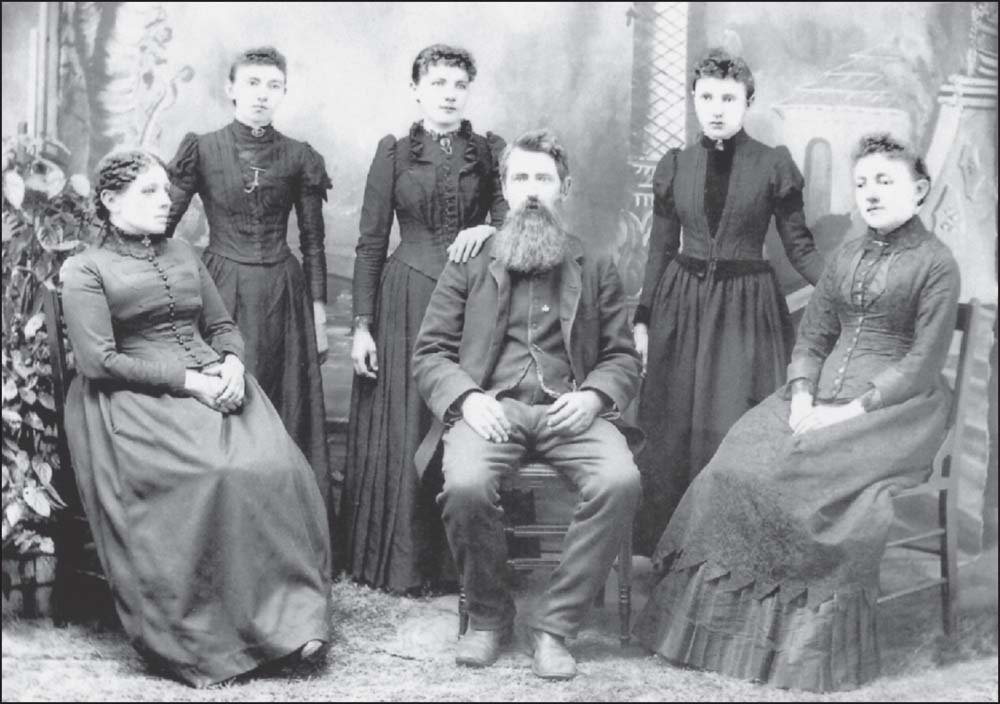

The family of Charles Ingalls became the first family of De Smet when they followed the Chicago and North Western Railway to Dakota Territory. The family includes, from left to right, Caroline, Carrie, Laura, Charles, Grace, and Mary. Charles worked as the timekeeper and paymaster for the railroad. He played an active part in the development of De Smet and had the distinction of being the first justice of the peace and the first town clerk.

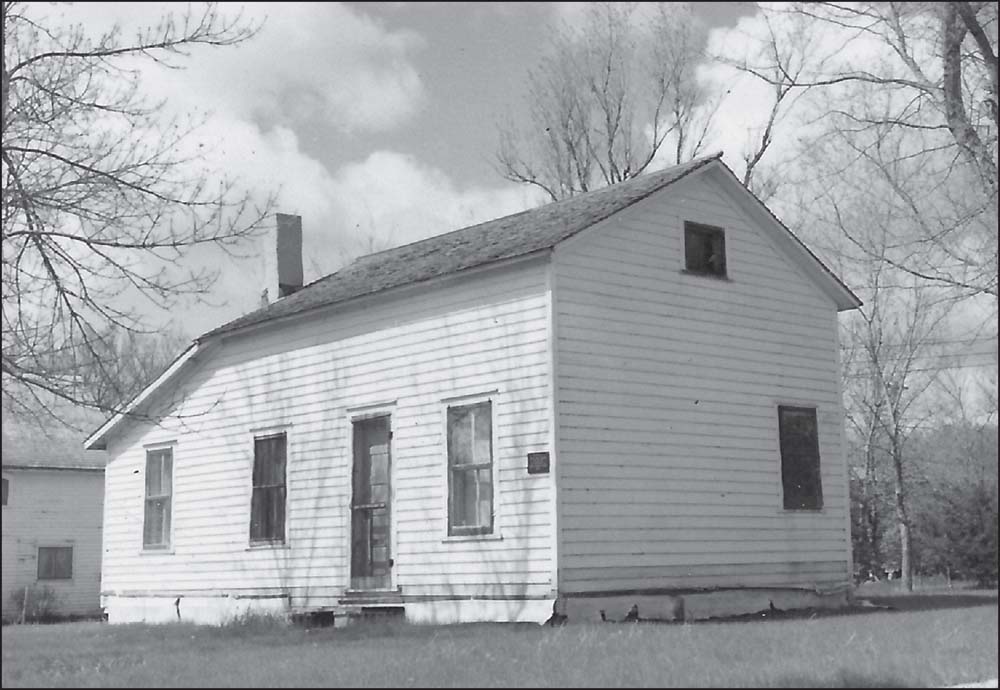

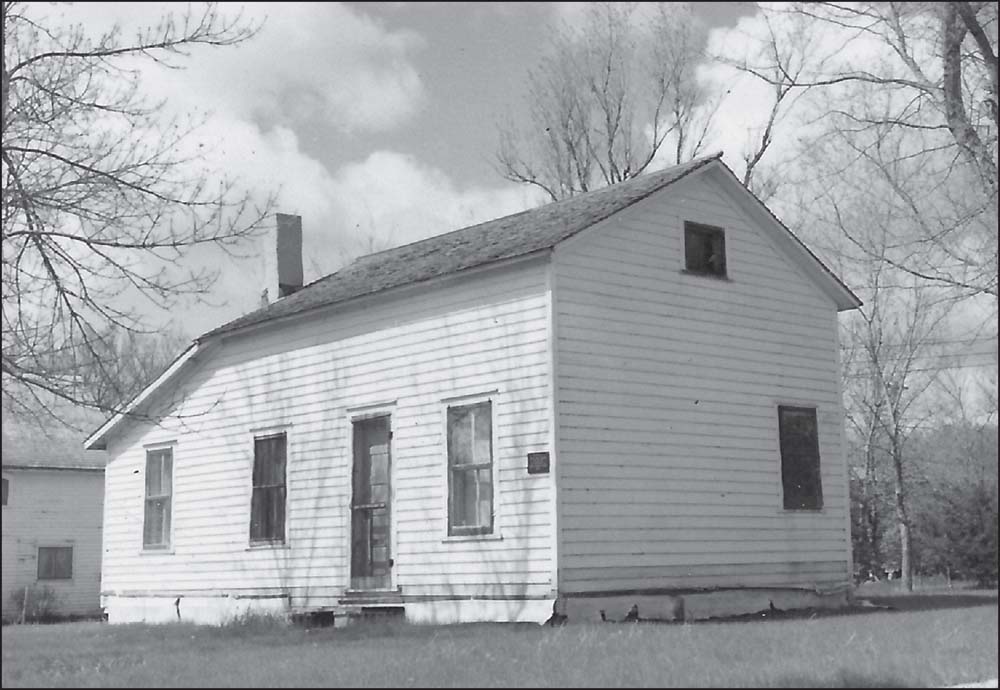

The surveyor’s house is the oldest building in De Smet; it was built in 1879, a year before there was even a town. Built by the Dakota Central Railroad (a branch of the Chicago and North Western), it was located on the north shore of Silver Lake. The Charles Ingalls family lived here during the winter of 1879–1880. In 1884, the house was moved near the east end of the railroad switch in De Smet.

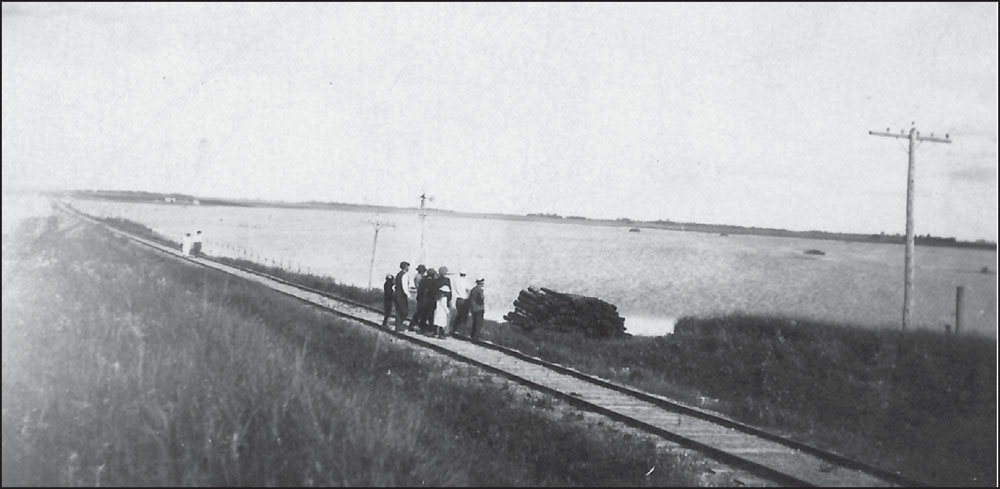

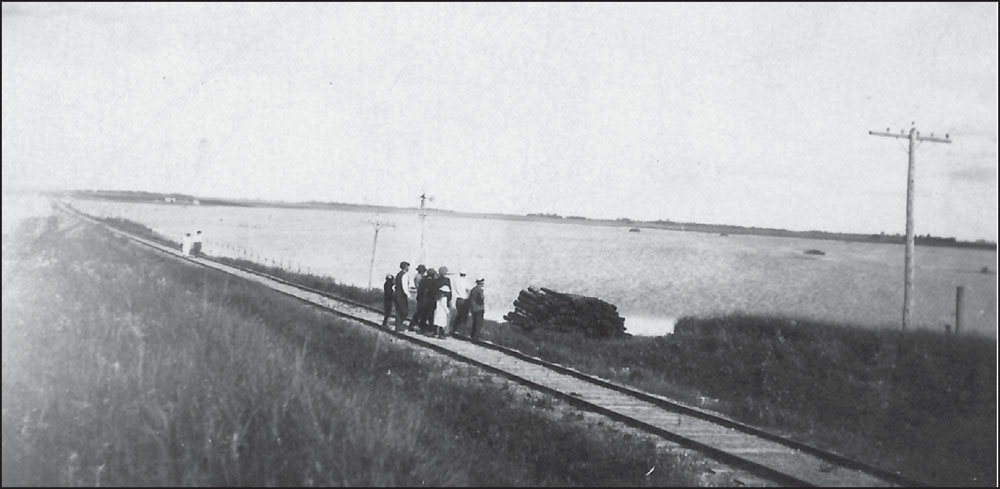

Silver Lake, located on the southeast edge of De Smet, has a long and interesting history. The Ingalls family arrived in 1879 to a “beautiful little lake full of water.” Over the years, ditching efforts were made to drain Silver Lake into Lake Henry. During the 1980s, extensive rains filled the lake, making it a full body of water once more. Old-timers of De Smet recall learning to ice-skate on Silver Lake. Frozen rushes stood along the paths they skated on, and when they needed a rest, they would sit on a muskrat house.

De Smet, South Dakota, became a literary landmark in the 1930s when Laura Ingalls Wilder began publishing her Little House books. Laura felt her childhood memories were “altogether too good to be lost,” so she began writing her series of books. De Smet is the setting for five of her books, and with them she preserved the early history of the city.

Harvey Dunn (far right), a prairie painter, visits with Aubrey Sherwood (far left) at Dunn’s 1950 art exhibit, held in De Smet’s Masonic Temple. Dunn, a native of Manchester, South Dakota, was adopted by the residents of De Smet, and he returned many times for Old Settlers Day. He gave four of his original paintings to the De Smet library and one to the American Legion. All five are displayed at the Hazel L. Meyer Memorial Library.

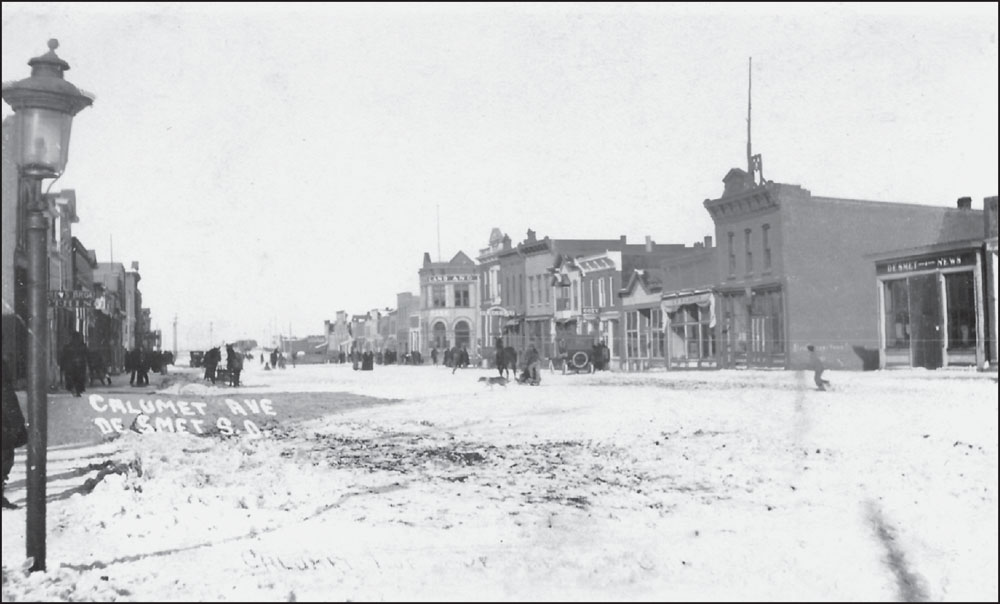

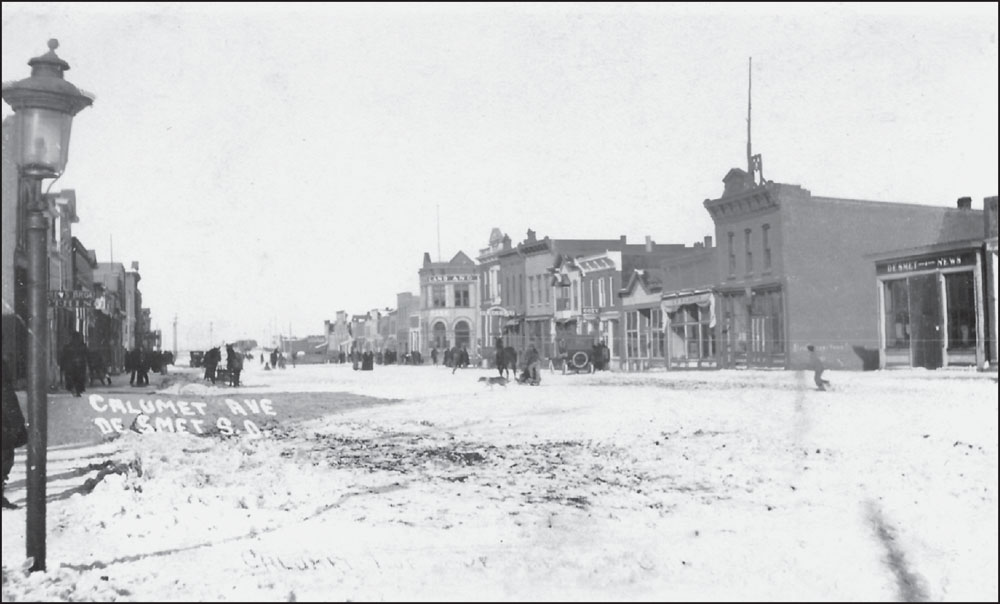

De Smet was a typical railroad town, with wooden sidewalks, gaslights on the main street, and barns in backyards for the milk cows. During the time that this image was taken, Robert Boast, a prominent resident and street commissioner, would not have to run a water truck to keep the dust from blowing down Calumet Avenue because the snow-covered street gave the board riders a clean trip to their destination.

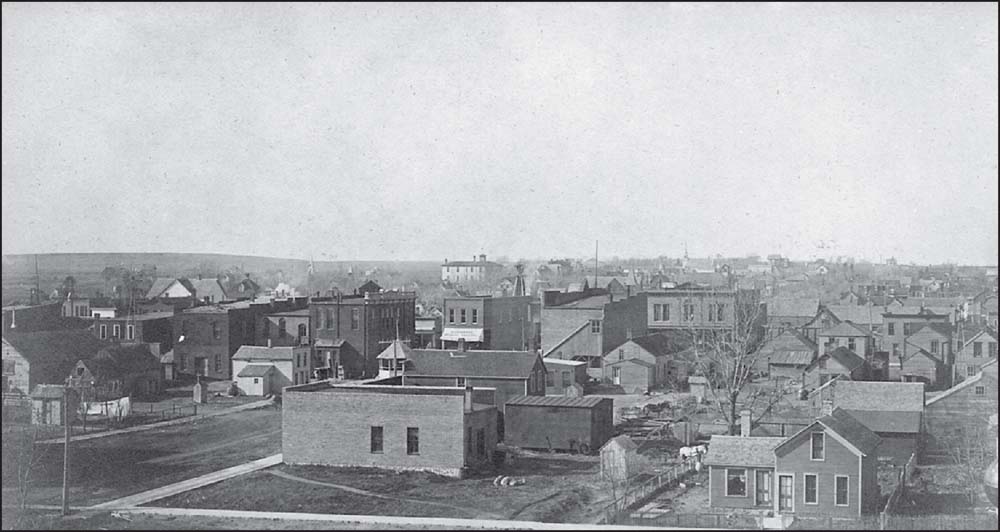

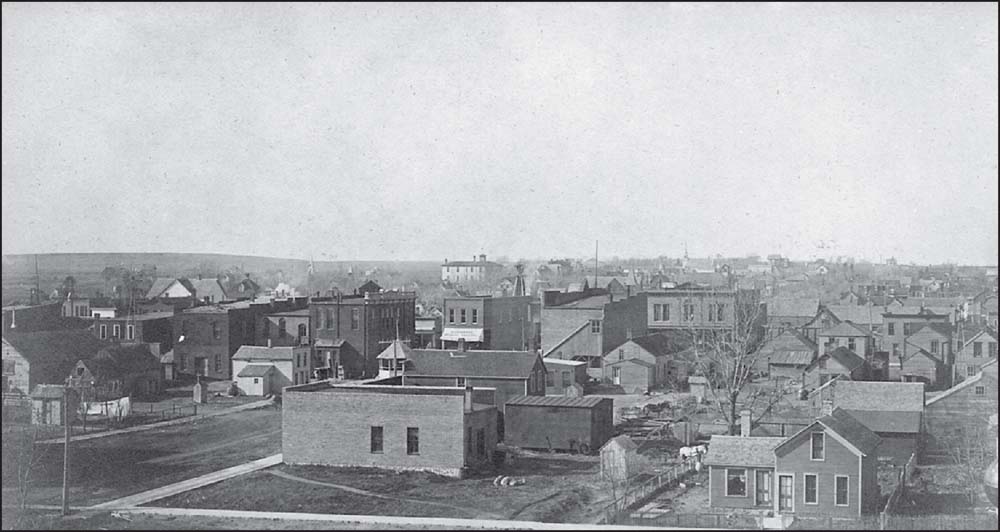

Main Street slowly emerged from early tar-papered, quickly built structures to those more fit to stand the test of time. This view is looking south from Second Street along the west side of Calumet Avenue.

Kingsbury County was organized at the Amos Whiting homestead in 1880. The county was named for the Kingsbury brothers, who were prominent in territorial affairs. This stately courthouse was completed in 1898.

Momentum was taking the little town to greater places when it became the county seat in 1888. This austere courthouse was constructed for the people of Kingsbury County in 1898, and the west part was added in 1892.

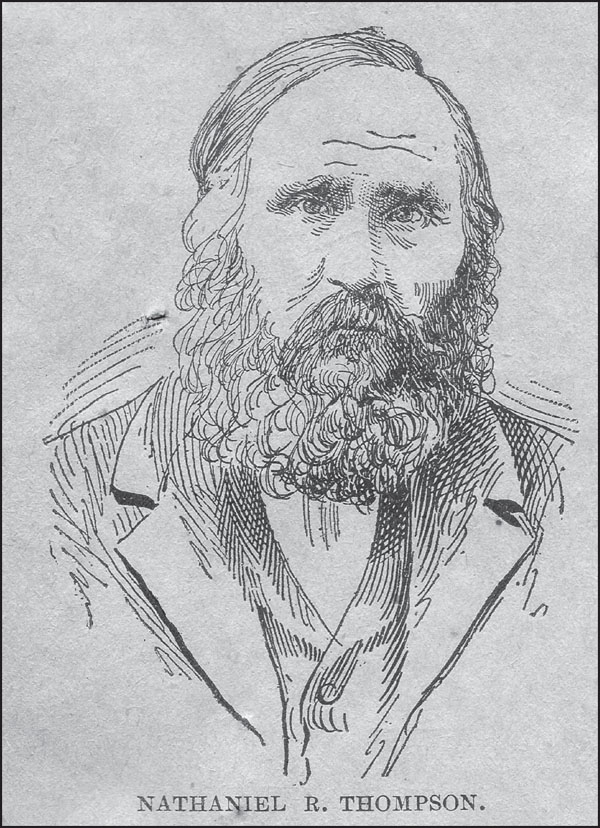

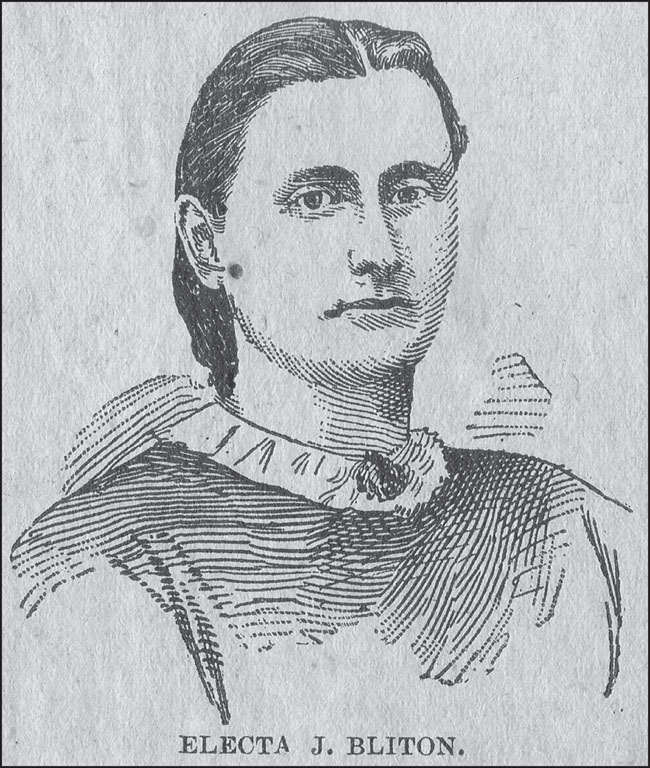

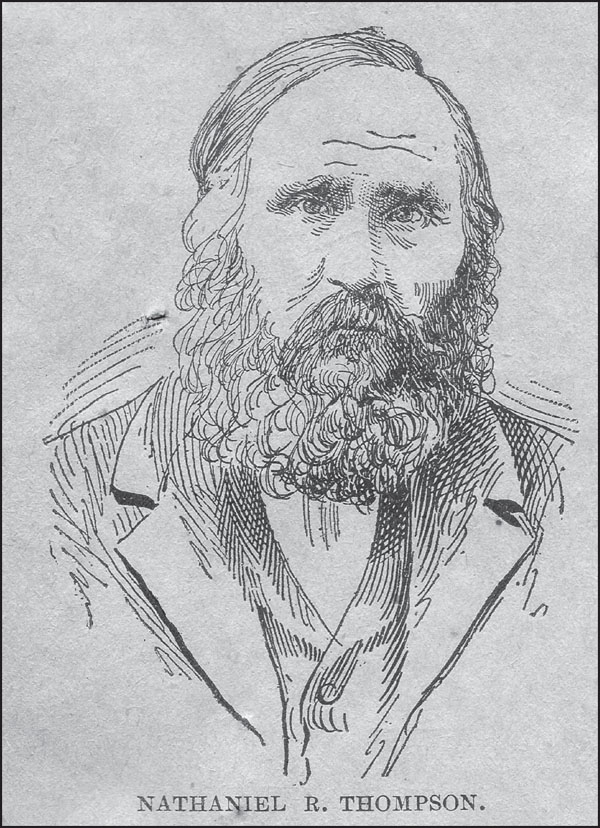

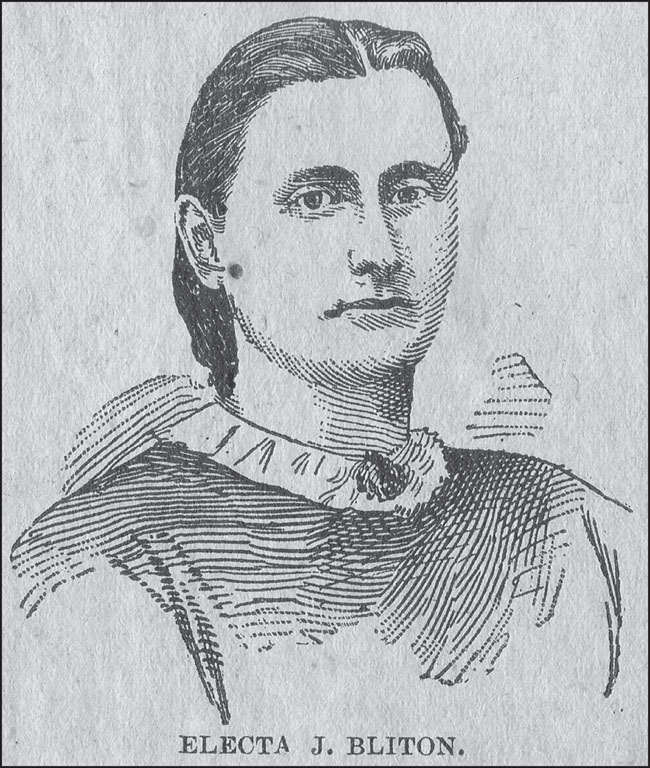

When Nathaniel Thompson was put to death in 1893 by hanging, it was the first execution in not only De Smet, but in the state of South Dakota since its organization. Thompson stabbed Electa Bliton (Arlington) to death. R.H. Richardson was the county sheriff and made arrangements for the execution that took place in the jail yard, which was surrounded by a high fence to shut out proceedings from the public eye.

Mrs. Thompson had filed for divorce because of cruel and inhumane treatment from her husband, Nathaniel, and his son. She was cared for by the ladies’ benevolent society and housed at the home of Electa Bliton after being carefully examined by the commissioners of insanity, where her husband had taken her for treatment. The trial went on for more than one year.

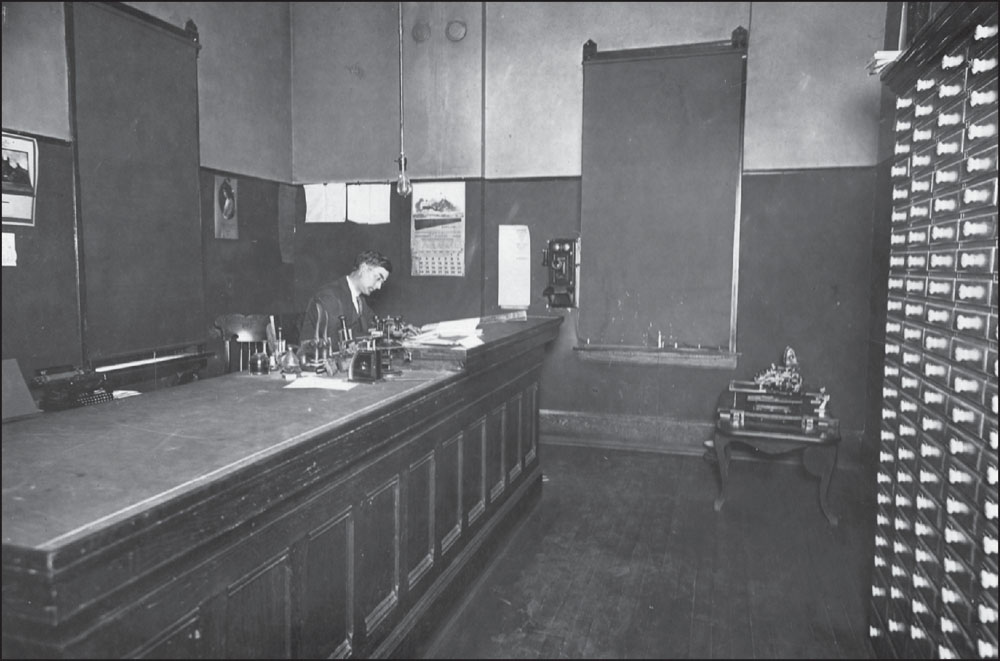

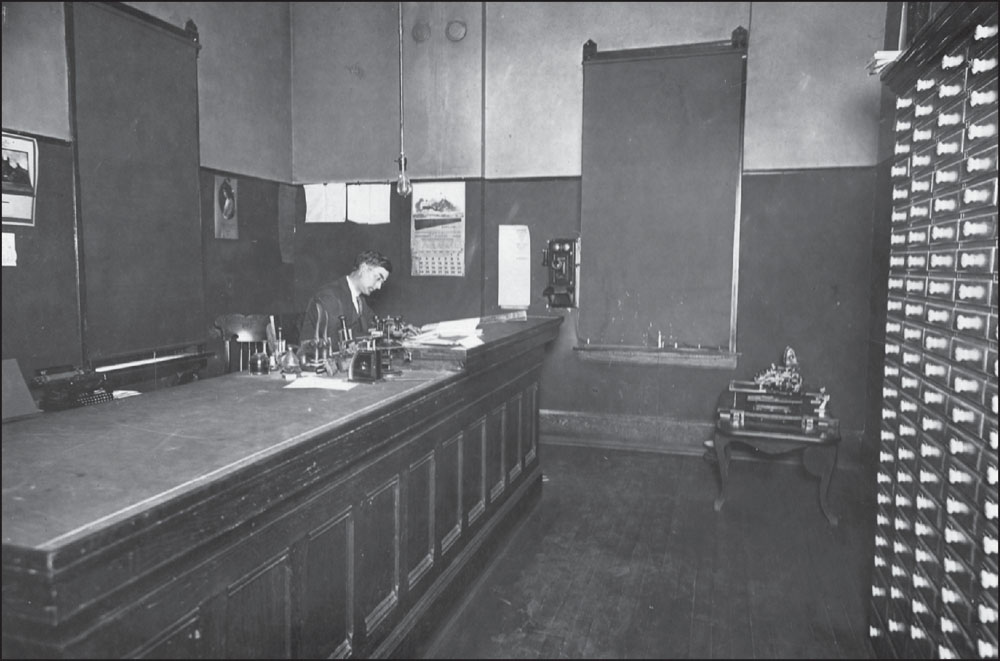

Shown here is the clerk of courts’ office in the Kingsbury County Courthouse, De Smet, South Dakota. E.F. Ruskell served as the clerk of courts from 1915 to 1917 and appears in this picture. The wall calendar shows the date to be in September 1916.

The cloud of war hung over De Smet in World War I. The first military draft since the Civil War called thousands of men into uniform. Enshrined on the World War I memorial (off the northwest corner of the courthouse) are the names of those who served from Kingsbury County. The plaque reads, “In Honor of the Boys from Kingsbury County, dedicated November 11, 1920.” The couple shown here is unidentified.

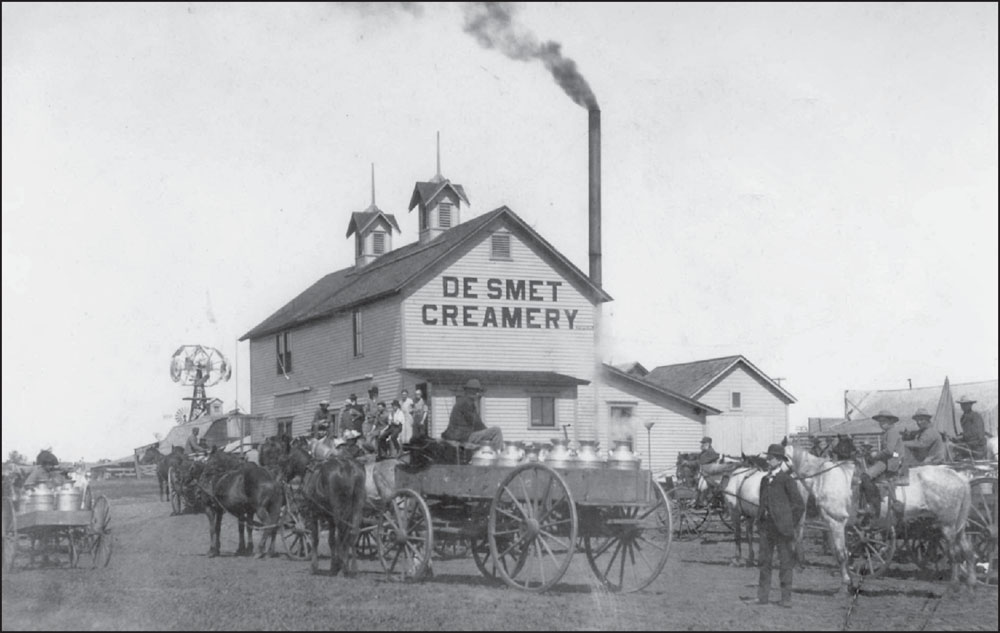

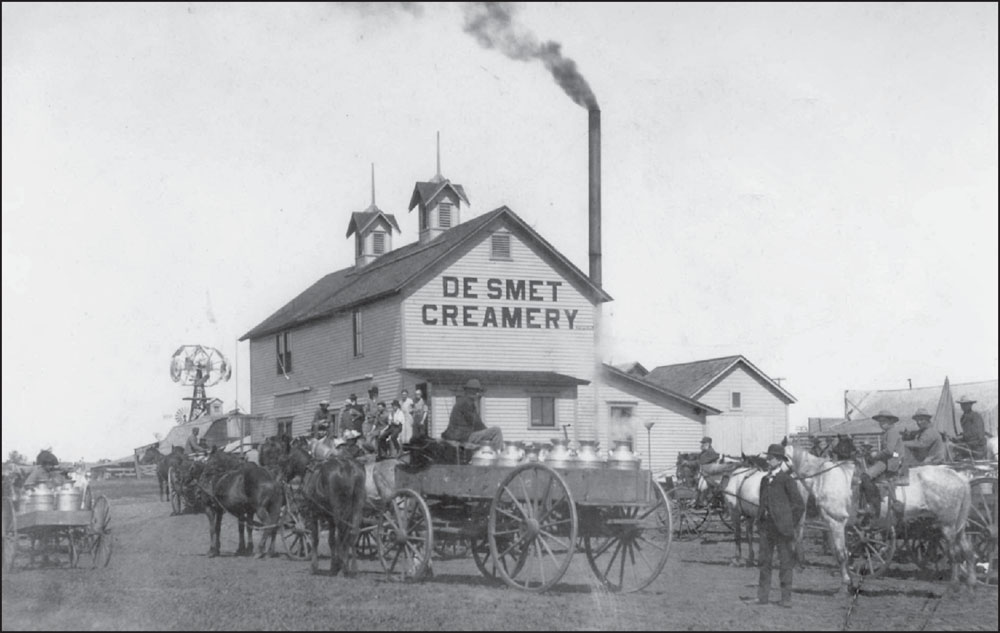

An important commodity, cream was a moneymaker, hence the nickname “Cream City” in early De Smet. Seen in this c. 1900 photograph are cans of cream being brought to the De Smet Creamery to be weighed and purchased by the creamery. Jack Distad, a butter maker, stands at the entry; C.P. Sherwood stands in suit and hat in the foreground. The O’Keefe Building is on the right.

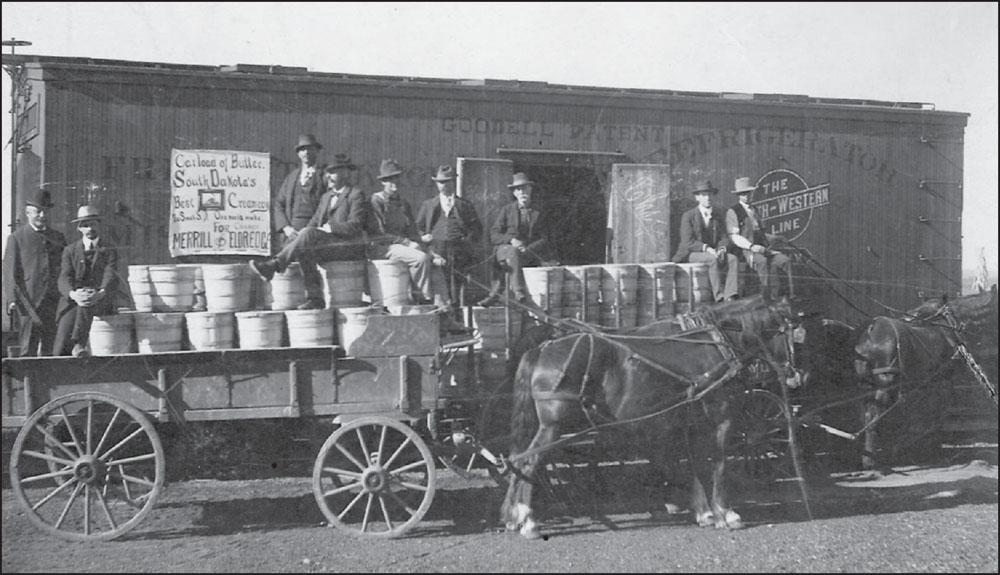

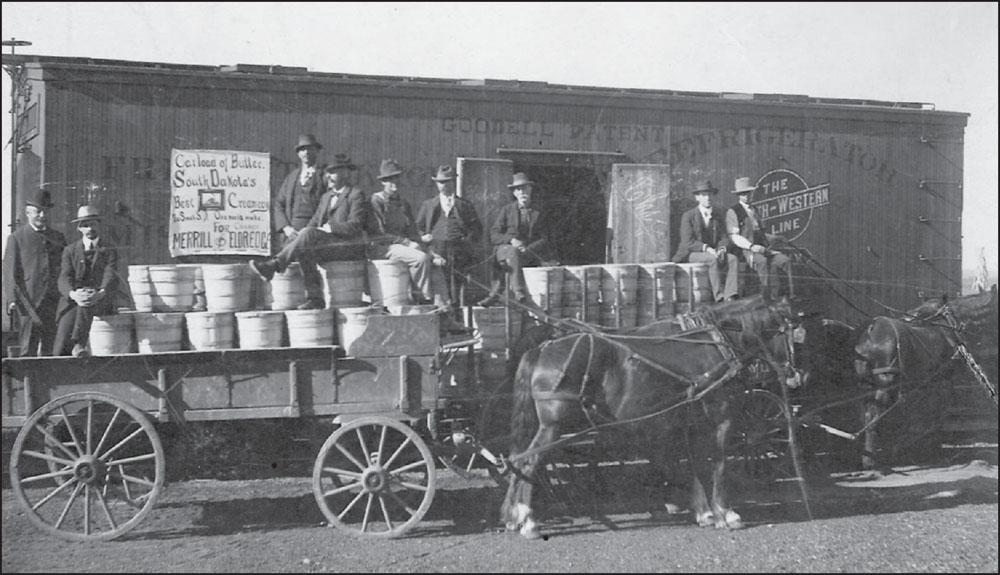

Bringing firm, chilled butter from farm to market was the intent of the North Western Line as it had a carload leaving De Smet in the Goodell Patent refrigerator car, headed for Merrill and Eldredge. It is hard to believe all the wooden buckets hold butter. Pictured, from left to right, are ? Stewart, C.P. Sherwood, unidentified, A.L. Waters (sitting), unidentified, Frank Andrews, A.L. Griffin (chief butter maker), Harry Hubbard, and unidentified.

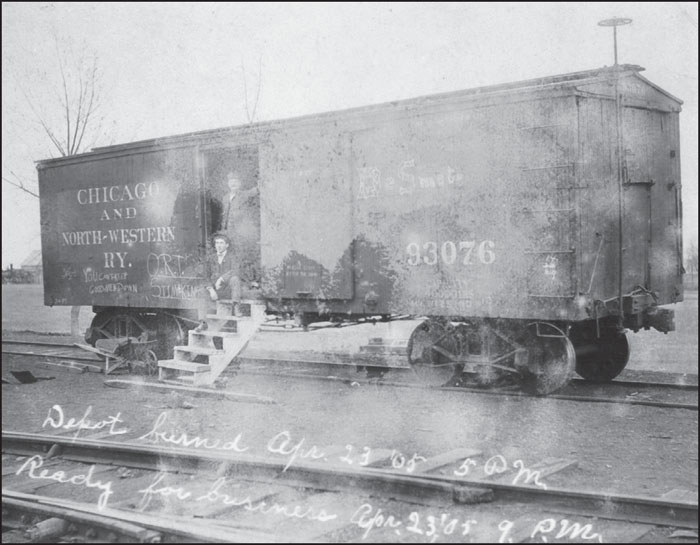

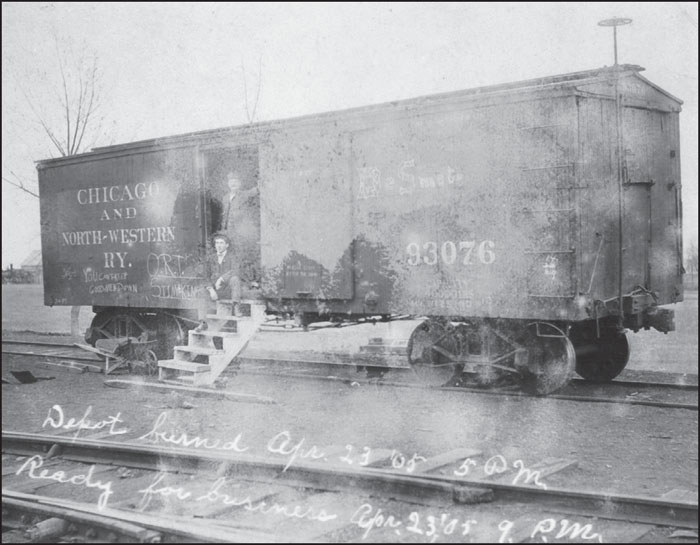

This converted boxcar is open and ready for business, as usual. This unique depot was set up after De Smet’s original, two-story building burned to the ground in 1905. The notation on the picture states the depot burned at 5:00 p.m. and the railroad was ready for business by 9:00 p.m. the same day, April 12, 1905.

Built in 1905–1906, this structure replaced the two-story depot that burned down. The fire started when a match head snapped off and set the heavily oil-soaked, pine floor ablaze. This building now houses the De Smet City Museum and still stands on the original plat. The signal pole stands at the peak of the building and remains outside the depot today. Switches are mounted inside on the wall between the two windows.

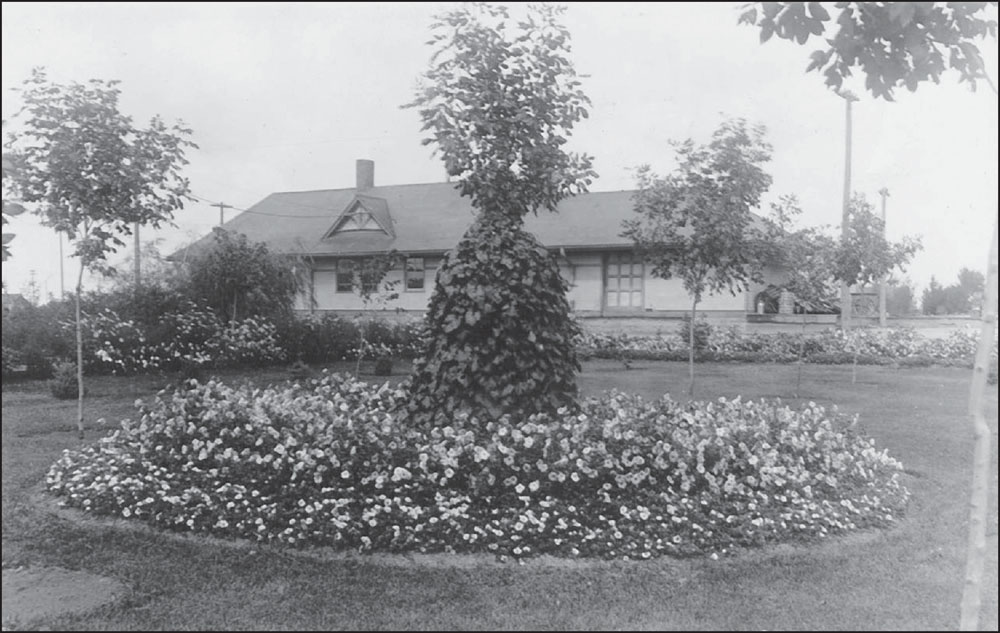

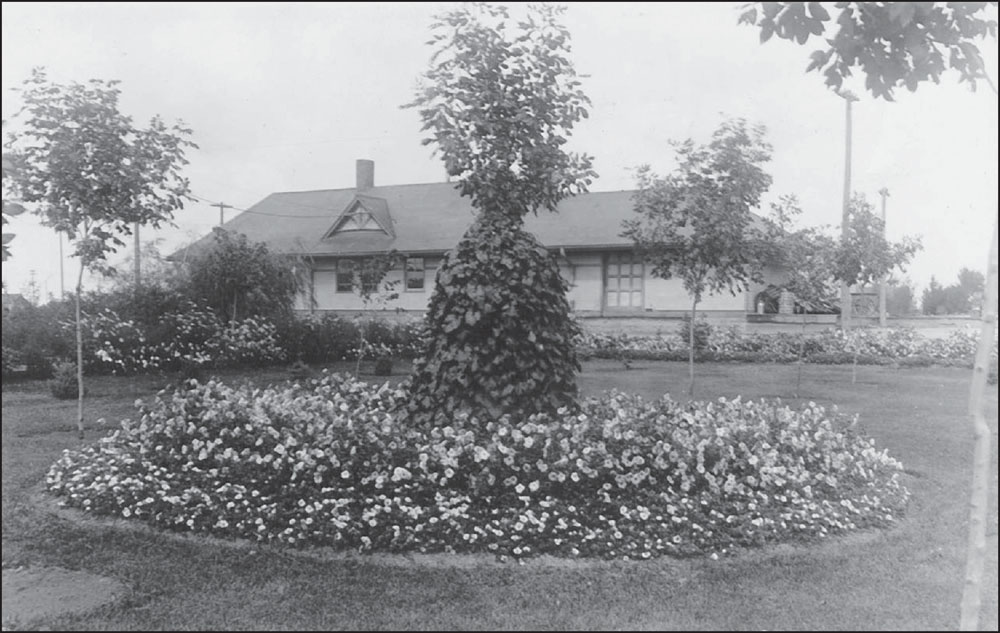

One conductor on the Chicago North Western Line remarked, “We’ll be seeing the prettiest park on the line,” meaning the railroad park at De Smet. Here, flowers circle a vine-covered tree while flowers line the perimeter and trees can be seen in the park itself. Many children recall playing hide-and-seek or other games in this park.

A wooden water tower, filled by the windmill, sits between the tracks on the northeast side of the depot, allowing for easy access for the steam locomotives to fill their tanks. A quarter of a million miles of railroad tracks crossed the nation in 1916, the peak of the train’s popularity as a means of travel.

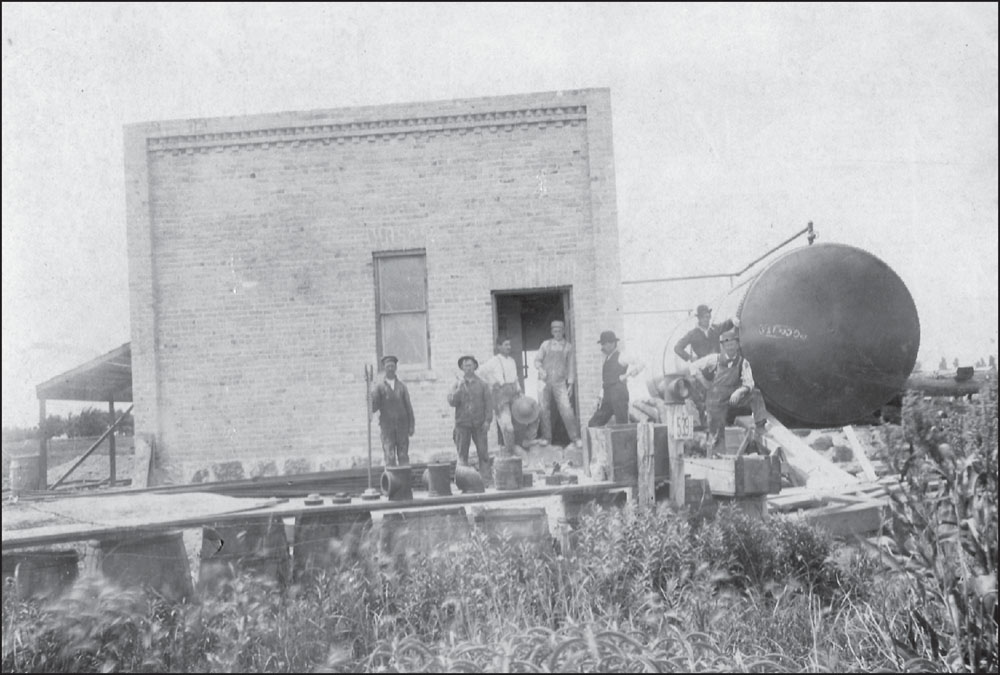

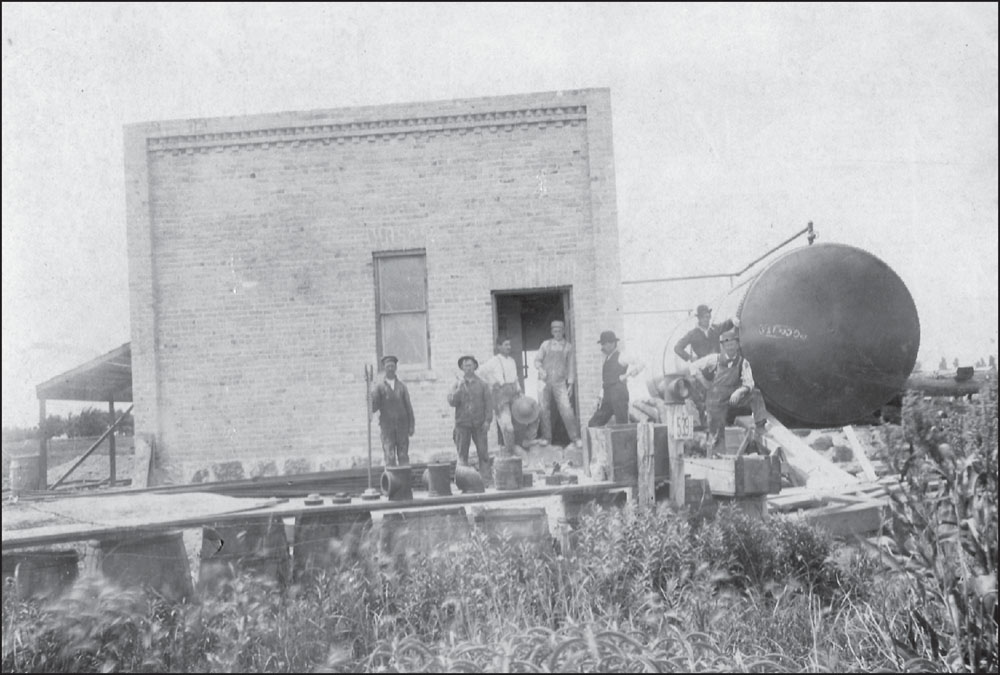

In 1903, the city’s gas plant provided the means for the homes, businesses, and streetlights to be kept alight. An early news article states the plant was located in the former auto sales building (now the vicinity of the fire hall on Highway 25). The oil, burned to make gas, was shipped in by rail and piped to the large tank seen on the right side of the picture.

Belching smoke, the city’s gas plant is ablaze in 1904. Sediment and frost combined to fill up the mains so gas could not get through. However, some good comes from all, and the gas became more satisfactory due to the mains being cleaned after the fire.

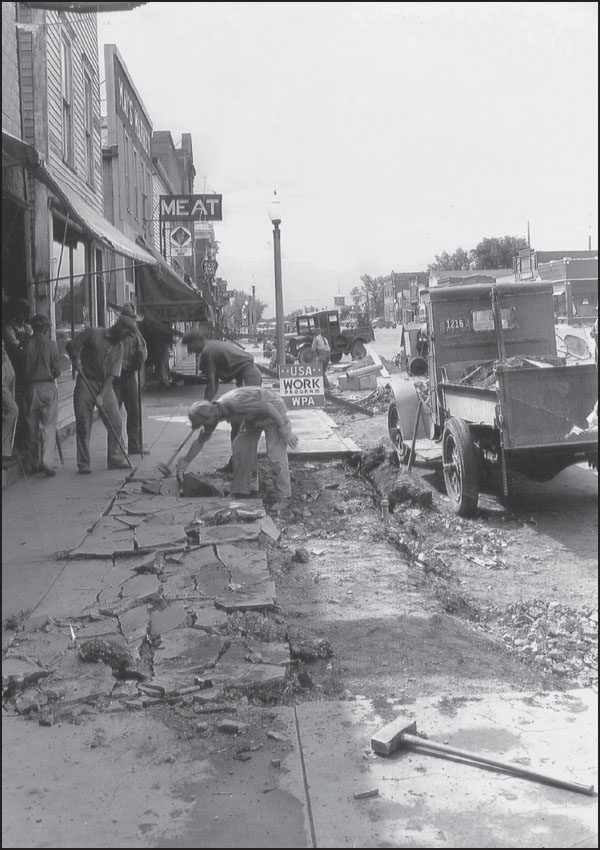

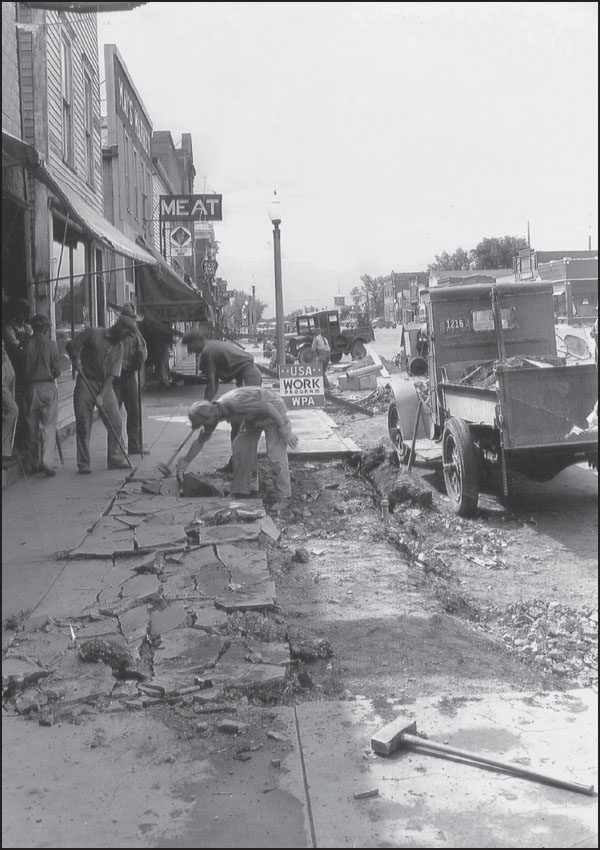

In 1936, the WPA (Works Progress Administration) came to the rescue of De Smet’s east-side Calumet Avenue sidewalks. Down the street, Mays Meat Market, a beauty shop, and the large Red Owl sign standing out from the storefront can be seen.

A dog never misses the chance to leave a lasting impression in fresh cement, and it appears the WPA men are diligently working on smoothing out the prints. There certainly appear to be many establishments that are readily selling libations. Across the street, a stately hotel occupies the corner, the Chevrolet garage has gas pumps, and the De Smet Lumber Co. sign is readable.

Shown here is a classic example of firefighting equipment and men in early De Smet. Few sounds are as frightening as the sound of the fire whistle; but thanks in part to Benjamin Franklin, who promoted organized firefighting in Philadelphia in the 1700s that set an example for the nation, these volunteers appear to be ready to handle the call.

Firemen pose on the east side of Washington Park on June 10, 1941. They are, from left to right, (first row) Glen Van Tassel, Forest Cook, Harlan Hoy, Rod Brandt, Ben Rehfield, Ernie Johnson, Russ Hunter, Lawrence McKibben, Ron Graham, Ray White, Art Christensen, Art Enderly, Barney Hasche, Alfred Ryland, and Darrell Freeman; (second row) Ollie Schoonover, Theodore Smith, Reginald Smith, Ted Haughn, Doc Paul Tschetter, and Kerm Buchele.

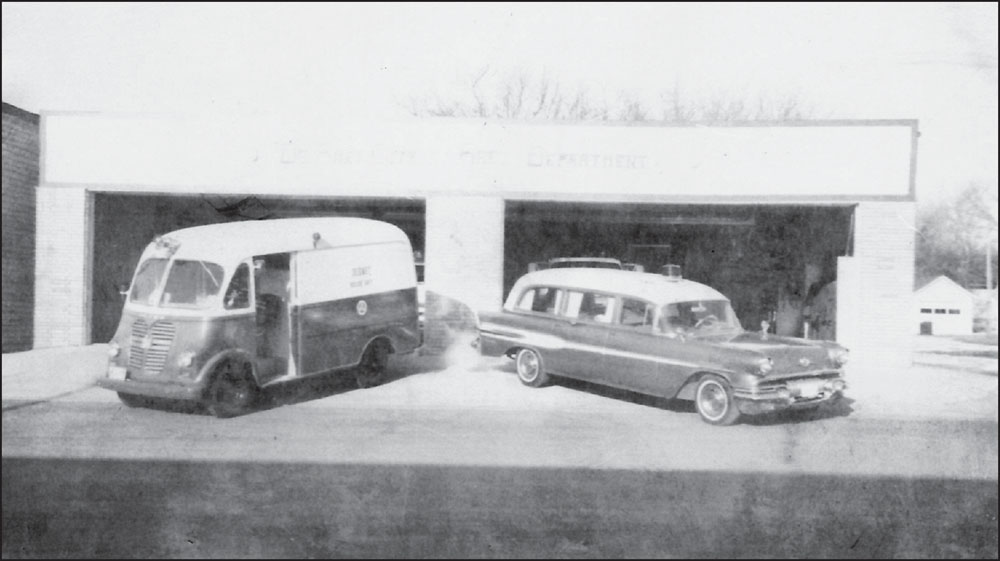

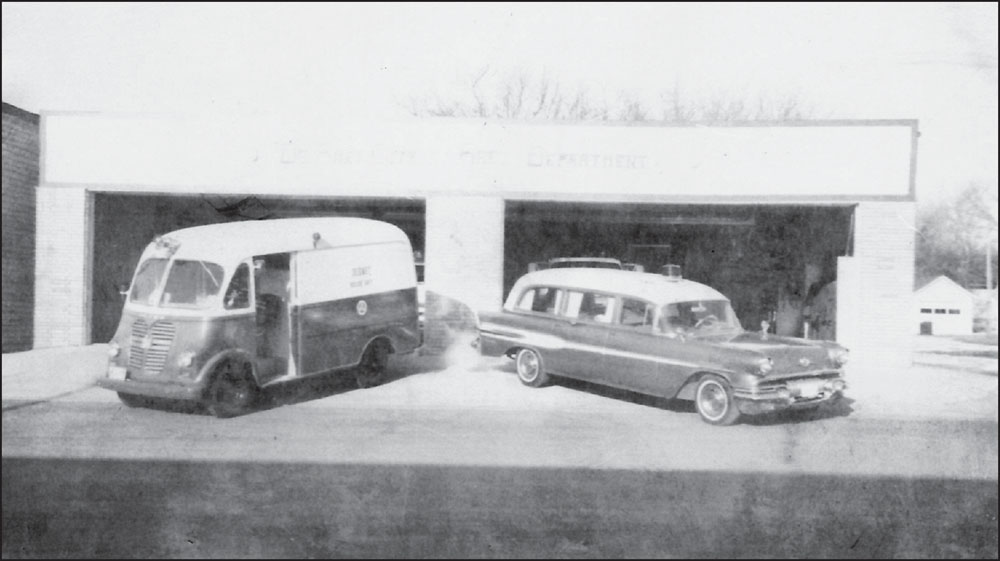

Some of the members of the fire department in the 1960s include, from left to right, (first row) Frosty Tibbetts, Dale Snyder, Dr. Robert Bell, Dr. William Hanson, Jim Burvee, and Leon Carpenter; (second row) Bill Purrington, Art Flindt Jr., Don Torgeson, Dave Harris, and Tex Myers. All have a relaxed look as they pose in front of the 1960s ambulance.

The department has come a long way from these two “new” ambulances, but the picture brings a ready smile to all who remember how the city thought these vehicles were “right uptown.” The ambulance on the right is a former hearse that was given to the fire department by local mortician Marvin Ketelsen.

Organized fire departments have always been a must, beginning with the bucket brigade and continuing right on through today. The earlier trucks and gear were housed in the building to the left, on the east side of Calumet Avenue. The early library can also be seen just to the fire hall’s right.

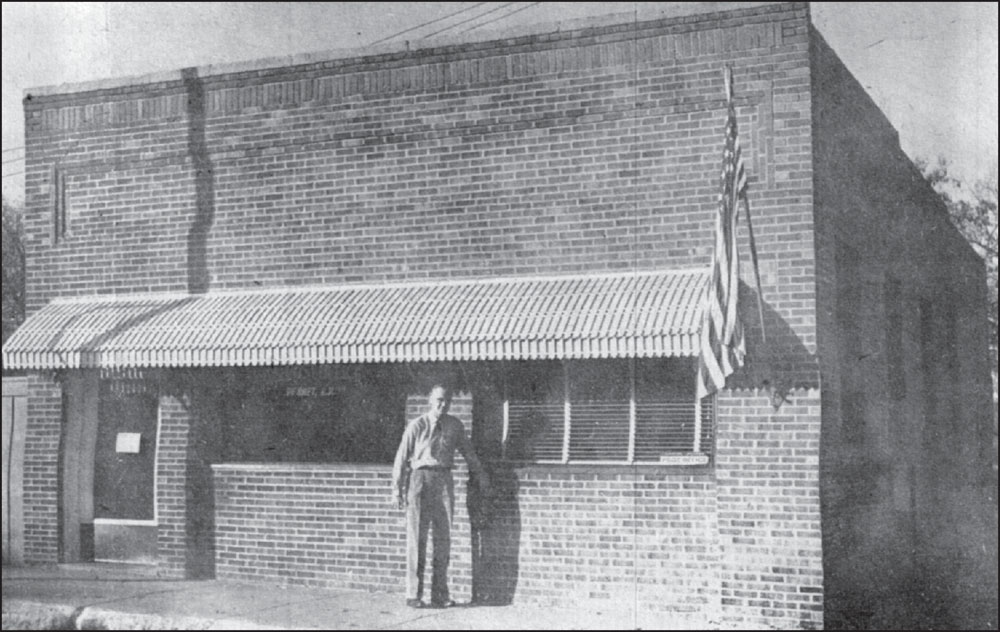

Volunteer firemen proudly stand before the fire station, built in 1964. Though it is no longer the fire station, the building still stands in the 300 block of southwest Calumet Avenue.

Relocated from a room in city hall after 31 years, the public library in De Smet was finally given a home at the Hazel L. Meyer Memorial Library. On the corner of Calumet and First Street, the land was donated by S. Neal Meyer and Roy Hanson for this new building site. Substantial funds from Meyer and his mother, Hazel, along with private donations and matching federal money, paid for the library in 1968.

Part of the Firefighter’s Pledge, “the love to serve unselfishly whenever I am called” took a new dimension on September 11, 2001, when an attack was made on the World Trade Center in New York. Each September 11, De Smet firefighters arrange a tribute in front of De Smet’s fire hall in memory of firefighters lost in the 9/11 attacks. Built in 2010, it currently houses six fire trucks and two ambulances for the 30 volunteer firemen.

Life seemed good to many when a person could walk to the end of the front walk and gather the mail. This postal deliveryman has full bags on his motorized bicycle. De Smet applied for its first post office on March 24, 1880. To the authors’ knowledge, the post office buildings have always been on Calumet Avenue or Second Street.

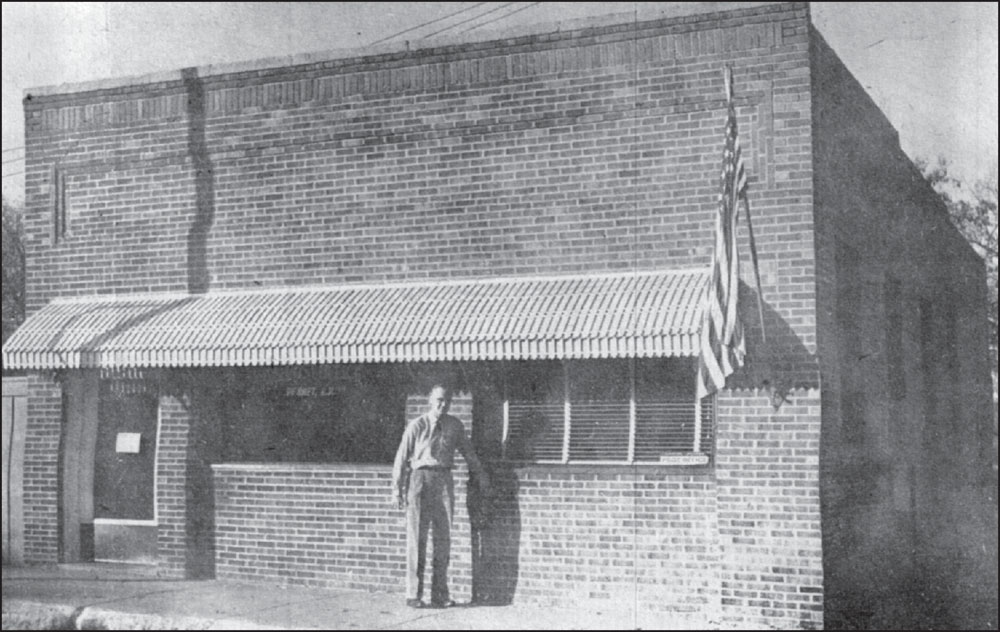

After 31 years, the flag came down at the old post office in 1960. Hollis Hill, postmaster, stands in front of the brick structure on Second Street. The post office moved to Calumet Avenue, where the Sturgeon Hotel sat at one time. Later years saw the old post office building serving the offices of Farmers Home Administration from 1960 to 1972, and as the dental office of Dr. Dan Slaight from 1972 to 2013.