OF THE SIX PEOPLE who started PayPal, four had built bombs in high school.

Five were just 23 years old—or younger. Four of us had been born outside the United States. Three had escaped here from communist countries: Yu Pan from China, Luke Nosek from Poland, and Max Levchin from Soviet Ukraine. Building bombs was not what kids normally did in those countries at that time.

The six of us could have been seen as eccentric. My first-ever conversation with Luke was about how he’d just signed up for cryonics, to be frozen upon death in hope of medical resurrection. Max claimed to be without a country and proud of it: his family was put into diplomatic limbo when the USSR collapsed while they were escaping to the U.S. Russ Simmons had escaped from a trailer park to the top math and science magnet school in Illinois. Only Ken Howery fit the stereotype of a privileged American childhood: he was PayPal’s sole Eagle Scout. But Kenny’s peers thought he was crazy to join the rest of us and make just one-third of the salary he had been offered by a big bank. So even he wasn’t entirely normal.

The PayPal Team in 1999

Are all founders unusual people? Or do we just tend to remember and exaggerate whatever is most unusual about them? More important, which personal traits actually matter in a founder? This chapter is about why it’s more powerful but at the same time more dangerous for a company to be led by a distinctive individual instead of an interchangeable manager.

Some people are strong, some are weak, some are geniuses, some are dullards—but most people are in the middle. Plot where everyone falls and you’ll see a bell curve:

Since so many founders seem to have extreme traits, you might guess that a plot showing only founders’ traits would have fatter tails with more people at either end.

But that doesn’t capture the strangest thing about founders. Normally we expect opposite traits to be mutually exclusive: a normal person can’t be both rich and poor at the same time, for instance. But it happens all the time to founders: startup CEOs can be cash poor but millionaires on paper. They may oscillate between sullen jerkiness and appealing charisma. Almost all successful entrepreneurs are simultaneously insiders and outsiders. And when they do succeed, they attract both fame and infamy. When you plot them out, founders’ traits appear to follow an inverse normal distribution:

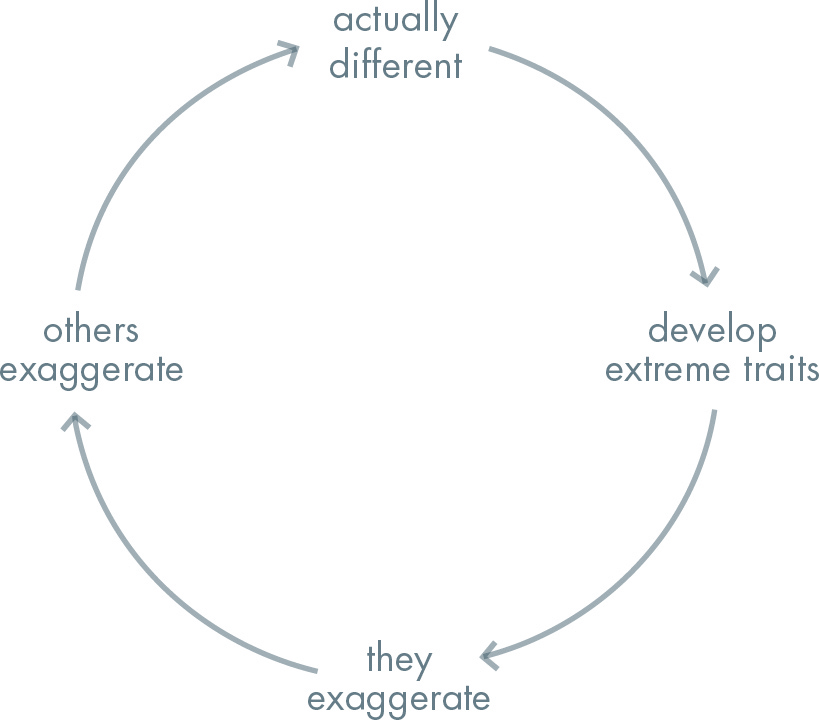

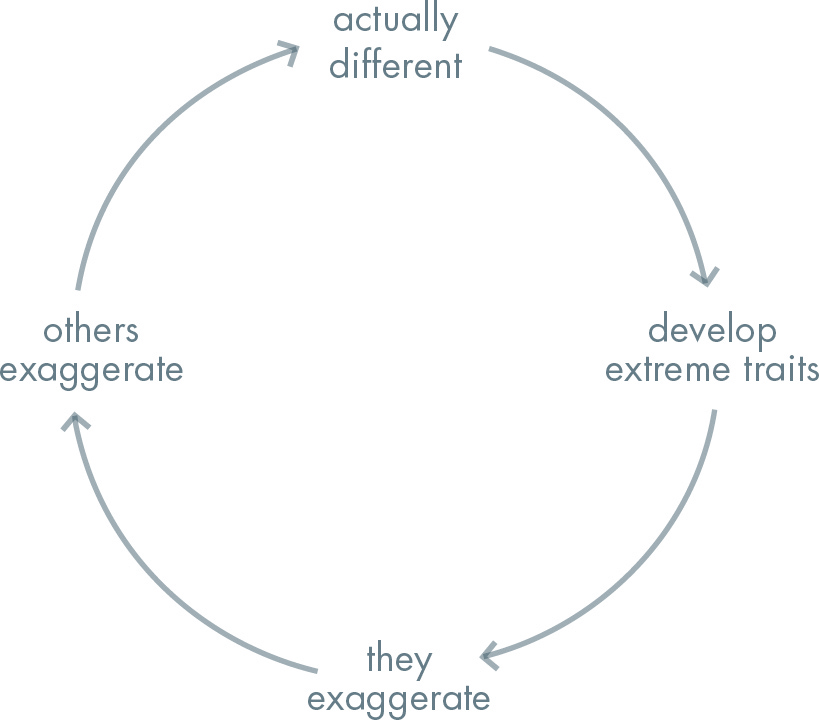

Where does this strange and extreme combination of traits come from? They could be present from birth (nature) or acquired from an individual’s environment (nurture). But perhaps founders aren’t really as extreme as they appear. Might they strategically exaggerate certain qualities? Or is it possible that everyone else exaggerates them? All of these effects can be present at the same time, and whenever present they powerfully reinforce each other. The cycle usually starts with unusual people and ends with them acting and seeming even more unusual:

As an example, take Sir Richard Branson, the billionaire founder of the Virgin Group. He could be described as a natural entrepreneur: Branson started his first business at age 16, and at just 22 he founded Virgin Records. But other aspects of his renown—the trademark lion’s mane hairstyle, for example—are less natural: one suspects he wasn’t born with that exact look. As Branson has cultivated his other extreme traits (Is kiteboarding with naked supermodels a PR stunt? Just a guy having fun? Both?), the media has eagerly enthroned him: Branson is “The Virgin King,” “The Undisputed King of PR,” “The King of Branding,” and “The King of the Desert and Space.” When Virgin Atlantic Airways began serving passengers drinks with ice cubes shaped like Branson’s face, he became “The Ice King.”

Is Branson just a normal businessman who happens to be lionized by the media with the help of a good PR team? Or is he himself a born branding genius rightly singled out by the journalists he is so good at manipulating? It’s hard to tell—maybe he’s both.

Another example is Sean Parker, who started out with the ultimate outsider status: criminal. Sean was a careful hacker in high school. But his father decided that Sean was spending too much time on the computer for a 16-year-old, so one day he took away Sean’s keyboard mid-hack. Sean couldn’t log out; the FBI noticed; soon federal agents were placing him under arrest.

Sean got off easy since he was a minor; if anything, the episode emboldened him. Three years later, he co-founded Napster. The peer-to-peer file sharing service amassed 10 million users in its first year, making it one of the fastest-growing businesses of all time. But the record companies sued and a federal judge ordered it shut down 20 months after opening. After a whirlwind period at the center, Sean was back to being an outsider again.

Then came Facebook. Sean met Mark Zuckerberg in 2004, helped negotiate Facebook’s first funding, and became the company’s founding president. He had to step down in 2005 amid allegations of drug use, but this only enhanced his notoriety. Ever since Justin Timberlake portrayed him in The Social Network, Sean has been perceived as one of the coolest people in America. JT is still more famous, but when he visits Silicon Valley, people ask if he’s Sean Parker.

The most famous people in the world are founders, too: instead of a company, every celebrity founds and cultivates a personal brand. Lady Gaga, for example, became one of the most influential living people. But is she even a real person? Her real name isn’t a secret, but almost no one knows or cares what it is. She wears costumes so bizarre as to put any other wearer at risk of an involuntary psychiatric hold. Gaga would have you believe that she was “born this way”—the title of both her second album and its lead track. But no one is born looking like a zombie with horns coming out of her head: Gaga must therefore be a self-manufactured myth. Then again, what kind of person would do this to herself? Certainly nobody normal. So perhaps Gaga really was born that way.

Extreme founder figures are not new in human affairs. Classical mythology is full of them. Oedipus is the paradigmatic insider/outsider: he was abandoned as an infant and ended up in a foreign land, but he was a brilliant king and smart enough to solve the riddle of the Sphinx.

Romulus and Remus were born of royal blood and abandoned as orphans. When they discovered their pedigree, they decided to found a city. But they couldn’t agree on where to put it. When Remus crossed the boundary that Romulus had decided was the edge of Rome, Romulus killed him, declaring: “So perish every one that shall hereafter leap over my wall.” Law-maker and law-breaker, criminal outlaw and king who defined Rome, Romulus was a self-contradictory insider/outsider.

Normal people aren’t like Oedipus or Romulus. Whatever those individuals were actually like in life, the mythologized versions of them remember only the extremes. But why was it so important for archaic cultures to remember extraordinary people?

The famous and infamous have always served as vessels for public sentiment: they’re praised amid prosperity and blamed for misfortune. Primitive societies faced one fundamental problem above all: they would be torn apart by conflict if they didn’t have a way to stop it. So whenever plagues, disasters, or violent rivalries threatened the peace, it was beneficial for the society to place the entire blame on a single person, someone everybody could agree on: a scapegoat.

Who makes an effective scapegoat? Like founders, scapegoats are extreme and contradictory figures. On the one hand, a scapegoat is necessarily weak; he is powerless to stop his own victimization. On the other hand, as the one who can defuse conflict by taking the blame, he is the most powerful member of the community.

Before execution, scapegoats were often worshipped like deities. The Aztecs considered their victims to be earthly forms of the gods to whom they were sacrificed. You would be dressed in fine clothes and feast royally until your brief reign ended and they cut your heart out. These are the roots of monarchy: every king was a living god, and every god a murdered king. Perhaps every modern king is just a scapegoat who has managed to delay his own execution.

Celebrities are supposedly “American royalty.” We even grant titles to our favorite performers: Elvis Presley was the king of rock. Michael Jackson was the king of pop. Britney Spears was the pop princess.

Until they weren’t. Elvis self-destructed in the ’70s and died alone, overweight, sitting on his toilet. Today, his impersonators are fat and sketchy, not lean and cool. Michael Jackson went from beloved child star to an erratic, physically repulsive, drug-addicted shell of his former self; the world reveled in the details of his trials. Britney’s story is the most dramatic of all. We created her from nothing, elevating her to superstardom as a teenager. But then everything fell off the tracks: witness the shaved head, the over- and under-eating scandals, and the highly publicized court case to take away her children. Was she always a little bit crazy? Did the publicity just get to her? Or did she do it all to get more?

For some fallen stars, death brings resurrection. So many popular musicians have died at age 27—Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, and Kurt Cobain, for example—that this set has become immortalized as the “27 Club.” Before she joined the club in 2011, Amy Winehouse sang: “They tried to make me go to rehab, but I said, ‘No, no, no.’ ” Maybe rehab seemed so unattractive because it blocked the path to immortality. Perhaps the only way to be a rock god forever is to die an early death.

We alternately worship and despise technology founders just as we do celebrities. Howard Hughes’s arc from fame to pity is the most dramatic of any 20th-century tech founder. He was born wealthy, but he was always more interested in engineering than luxury. He built Houston’s first radio transmitter at the age of 11. The year after that he built the city’s first motorcycle. By age 30 he’d made nine commercially successful movies at a time when Hollywood was on the technological frontier. But Hughes was even more famous for his parallel career in aviation. He designed planes, produced them, and piloted them himself. Hughes set world records for top airspeed, fastest transcontinental flight, and fastest flight around the world.

Hughes was obsessed with flying higher than everyone else. He liked to remind people that he was a mere mortal, not a Greek god—something that mortals say only when they want to invite comparisons to gods. Hughes was “a man to whom you cannot apply the same standards as you can to you and me,” his lawyer once argued in federal court. Hughes paid the lawyer to say that, but according to the New York Times there was “no dispute on this point from judge or jury.” When Hughes was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1939 for his achievements in aviation, he didn’t even show up to claim it—years later President Truman found it in the White House and mailed it to him.

The beginning of Hughes’s end came in 1946, when he suffered his third and worst plane crash. Had he died then, he would have been remembered forever as one of the most dashing and successful Americans of all time. But he survived—barely. He became obsessive-compulsive, addicted to painkillers, and withdrew from the public to spend the last 30 years of his life in self-imposed solitary confinement. Hughes had always acted a little crazy, on the theory that fewer people would want to bother a crazy person. But when his crazy act turned into a crazy life, he became an object of pity as much as awe.

More recently, Bill Gates has shown how highly visible success can attract highly focused attacks. Gates embodied the founder archetype: he was simultaneously an awkward and nerdy college-dropout outsider and the world’s wealthiest insider. Did he choose his geeky eyeglasses strategically, to build up a distinctive persona? Or, in his incurable nerdiness, did his geek glasses choose him? It’s hard to know. But his dominance was undeniable: Microsoft’s Windows claimed a 90% share of the market for operating systems in 2000. That year Peter Jennings could plausibly ask, “Who is more important in the world today: Bill Clinton or Bill Gates? I don’t know. It’s a good question.”

The U.S. Department of Justice didn’t limit itself to rhetorical questions; they opened an investigation and sued Microsoft for “anticompetitive conduct.” In June 2000 a court ordered that Microsoft be broken apart. Gates had stepped down as CEO of Microsoft six months earlier, having been forced to spend most of his time responding to legal threats instead of building new technology. A court of appeals later overturned the breakup order, and Microsoft reached a settlement with the government in 2001. But by then Gates’s enemies had already deprived his company of the full engagement of its founder, and Microsoft entered an era of relative stagnation. Today Gates is better known as a philanthropist than a technologist.

Just as the legal attack on Microsoft was ending Bill Gates’s dominance, Steve Jobs’s return to Apple demonstrated the irreplaceable value of a company’s founder. In some ways, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates were opposites. Jobs was an artist, preferred closed systems, and spent his time thinking about great products above all else; Gates was a businessman, kept his products open, and wanted to run the world. But both were insider/outsiders, and both pushed the companies they started to achievements that nobody else would have been able to match.

A college dropout who walked around barefoot and refused to shower, Jobs was also the insider of his own personality cult. He could act charismatic or crazy, perhaps according to his mood or perhaps according to his calculations; it’s hard to believe that such weird practices as apple-only diets weren’t part of a larger strategy. But all this eccentricity backfired on him in 1985: Apple’s board effectively kicked Jobs out of his own company when he clashed with the professional CEO brought in to provide adult supervision.

Jobs’s return to Apple 12 years later shows how the most important task in business—the creation of new value—cannot be reduced to a formula and applied by professionals. When he was hired as interim CEO of Apple in 1997, the impeccably credentialed executives who preceded him had steered the company nearly to bankruptcy. That year Michael Dell famously said of Apple, “What would I do? I’d shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders.” Instead Jobs introduced the iPod (2001), the iPhone (2007), and the iPad (2010) before he had to resign in 2011 because of poor health. By the following year Apple was the single most valuable company in the world.

Apple’s value crucially depended on the singular vision of a particular person. This hints at the strange way in which the companies that create new technology often resemble feudal monarchies rather than organizations that are supposedly more “modern.” A unique founder can make authoritative decisions, inspire strong personal loyalty, and plan ahead for decades. Paradoxically, impersonal bureaucracies staffed by trained professionals can last longer than any lifetime, but they usually act with short time horizons.

The lesson for business is that we need founders. If anything, we should be more tolerant of founders who seem strange or extreme; we need unusual individuals to lead companies beyond mere incrementalism.

The lesson for founders is that individual prominence and adulation can never be enjoyed except on the condition that it may be exchanged for individual notoriety and demonization at any moment—so be careful.

Above all, don’t overestimate your own power as an individual. Founders are important not because they are the only ones whose work has value, but rather because a great founder can bring out the best work from everybody at his company. That we need individual founders in all their peculiarity does not mean that we are called to worship Ayn Randian “prime movers” who claim to be independent of everybody around them. In this respect Rand was a merely half-great writer: her villains were real, but her heroes were fake. There is no Galt’s Gulch. There is no secession from society. To believe yourself invested with divine self-sufficiency is not the mark of a strong individual, but of a person who has mistaken the crowd’s worship—or jeering—for the truth. The single greatest danger for a founder is to become so certain of his own myth that he loses his mind. But an equally insidious danger for every business is to lose all sense of myth and mistake disenchantment for wisdom.