More than three decades after the first mobile phone call made by Martin Cooper of Motorola to rival Joel Engel at Bell Labs ,1 Nokia of Finland stood proud with more than 50% global market share during 2007 Q4, followed by Motorola and Samsung of South Korea to make the global big three. However, thanks to Apple’s iPhone, the deck was reshuffled in that same quarter and in just five years Nokia’s global market share had slipped to merely 3.1%.2 It was acquired by Microsoft for $7.9 billion in 2014 ($7.6 billion of which would be written off within less than two years).3 As of 2019, Samsung , Apple , and China’s Huawei rounded up the global three for smartphone manufacturers with Samsung in the lead with 20.4% and the other two vying for #2 spot, each with 14.4% global market share.4

At the outset of the last century, the U.S. had already surpassed England to become the largest and lowest-cost producer of steel globally. U.S. Steel Corporation alone accounted for two-thirds of the U.S. and almost 30% of world production, eventually followed by Bethlehem Steel , and Republic Steel to make the big three (unable to compete with low-cost competitors , both would go bankrupt in 2001). The U.S. produced more than 70% world steel by the end of World War II (WWII).5 Eventually, Nippon Steel of Japan and Posco of South Korea rose to prominence. Today, U.S. firms are nowhere to be found among the list of top ten leading global steel manufacturers which consists exclusively of Asian firms. The global leader in steel is ArcelorMittal (of India , headquartered in Luxembourg), followed by China Baowu Group and HBIS Group (also from China ). Indeed, Chinese firms produced more than ten times the steel produced by the U.S. in 2016.6

As the birthplace of the TV and home to more than 220 manufacturers in its heyday, the U.S. had every reason to be on the leading edge of the smart and HDTV market today.7 However, it never even had the chance. After going through its days of glory with brands such as RCA, Motorola , Westinghouse, and GE , when the last standing U.S. manufacturer Zenith was acquired by LG (of South Korea ) in 1995, it was merely the #3 player in the U.S. with under 10% share. The leader was Thomson of France with more than 20% share followed by Phillips (of the Netherlands) with 15% share. The deal propelled LG from 2% share in the U.S. to the top three.8 The same year the first flat-screen plasma TVs were introduced, and Japanese brands such as Sony , Sharp, Matsushita , and Toshiba began to shine. Yet today, even the Japanese have had to vacate the leaderboard. Samsung wrested global leadership from Sony in 2006 and has not looked back.9 It is currently the global LCD leader with over 20% share, followed by LG with 12% share and TCL (of China ) with 11% of the market.10

The globalization of the home appliances market can be traced back to then-world leader Electrolux’s acquisition of U.S. #3 player White Consolidated in the U.S. in 1986. Whirlpool retaliated by purchasing KitchenAid (in its home market) and Phillips’ appliance division to become #2 in Europe over Bosch-Siemens and Merloni. Whirlpool also acquired Maytag after a bidding war with Haier for $1.7 billion in 2006 to solidify its U.S. position. However, Haier declared its intention to be #1 globally, and building upon the strength of its domestic market, would not be denied for long. It initially started with smaller appliances and wiped out its Italian competitors . Haier then became a full-line appliance company competing successfully against global leaders Whirlpool and Electrolux . It finally became the global leader in 2009 and has further solidified its leadership with its acquisition of GE’s appliance division for $5.6 billion in 2016.11 Today, the chances are your new microwave oven which was likely to be made in Japan in the earlier days and subsequently in South Korea was actually made in China .

At first glance, all seems to be in order in the world of PC manufacturing. Based on 2018 figures, Lenovo (of China , formerly known as Legend) has the lead with 22.5% global market share, followed by HP 21.7% and Dell with 16.2%.12 However, this apparent order does not alleviate the ongoing intensive competition between HP and Lenovo , and the pressure on Dell’s position. In the next decade, it is possible for HP and Dell to not only fall out of contention for leadership but also become #3 and ditch players, respectively. Apple , which arguably pioneered personal computers, has become a specialist , and its archrival IBM long ago exited the PC manufacturing business.

In 1995, the year Amazon.com launched, Wal-Mart was already a well-entrenched incumbent with $89 billion in revenues.13 In all, the e-commerce industry is less than three decades old; however, global e-retail sales volume was expected to rise to $3.9 trillion in 2020.14 And despite the predictions of the early skeptics, there is no end in sight to the boom. Also, 17.5% of total global retail sales in 2021 are predicted to be online, still leaving ample room for future growth .15 The online retail sector has already globalized with Alibaba (31%; Taobao.com, Tmall.com), Amazon (15%), and Tencent (10%; JD.com, VIP.com, Yihaodian) taking the lead based on gross merchandise volume. Can you imagine a world where Walmart is not a global generalist ? Its global share of online retail stood merely at 1% in 2019.16

As Drucker observed in his usual penetrating style: “[t]he multinational corporation is both the response to the emergence of a common world market and its symbol…The multinational business is in every case a marketing business.”17 Meanwhile, we live in an era of unprecedented and disruptive change. Business leaders around the world are struggling to adapt, much less anticipate where the next wave of disruption will hit them. One cannot help but notice the winds of change. Who would’ve imagined that the innovators and captains of industry in the above examples would be global leaders no more?

The birthplace and home domain for marketing—distribution and retailing—have not fared much better when it comes to avoiding disruption. The market capitalization of leading retailers has been annihilated over the past decade. For example, Macy’s was down 55%, Kohl’s was down 64%, and JC Penney stock decreased 86% between 2006 and 2016, while Toys“R”Us and Sears are already bankrupt. Meanwhile, Amazon stock sat under $30 a share in August 2006. During the summer of 2020, it traded at over $2750 implying a return exceeding 9000%!18 In fact, when Amazon announced that it was buying Whole Foods for $13.7 billion cash in June 2017, its stock market capitalization appreciated by $15.6 billion; arguably, it acquired the company for free and pocketed $1.9 billion in the process!19

The average life span of an S&P 500 firm has gone down from 90 years in 1935 to under 18 years today20 and is decreasing fast.21 Ninety percent of Fortune 500 firms in 1955 (the inaugural year the list was announced), despite their might and vast resources are no longer in the list any more.22 Typical of the pace of the information age, early search firms of the tech era (Excite, Alta Vista, Netscape), online service providers (Prodigy, CompuServe, AOL), and PC manufacturers (Tandy, Commodore, IBM) are either out of manufacturing or out of business altogether.23

In our increasingly digital, mobile, and global world, the existing theories of business and economics have lost much of their relevance with the phenomenal rise of China and India,24 the phenomenon of Brexit, and the seismic shifting of the global economic center of gravity from West to East. The traditional thinking that a developed country, often the U.S., will come up with the next major innovation, launch at home first, and then take it to other markets does not ring true anymore. Over 3.5 billion smartphones are already in use globally, and with a wide variety of smartphones currently sold for less than $25,25 it is not hard to imagine a day when everyone will be able to connect, experience, and become global consumers alike. This will revolutionize business as well as society.

As mentioned earlier, this book is based on empirical analyses of hundreds of markets and industries in the U.S. and globally. Competitive markets evolve in a predictable fashion across industries and geographies, where every industry goes through a similar life cycle from beginning to end (or revitalizes itself). The pattern is so consistent that it represents a natural market structure at every level from local to regional to national and ultimately global, a structure that is not only common but one that also provides the highest levels of profitability and stakeholder well-being for the entire industry!

Academics have produced a number of theories that explain organizations and competitive strategy but there are few seminal theories of industry life cycle and evolution. In this book, we describe how markets/industries evolve systematically and attempt to put forth a coherent explanation to fill this void. We rely on our own analyses as well as extant research and anecdotal evidence to develop more convincing arguments. In particular, organizational ecology and industrial organization literatures provide further support to our claims, with empirical studies from film, newspapers, telecommunications, wineries, semiconductor manufacturers, and more.26 Even experimental research supports our main thesis of three major players and optimal profitability. Indeed, after conducting a meta-analysis of the literature and conducting a series of oligopoly experiments of their own, three experimental researchers concluded: “[t]wo are few and four are many.”27

Finally, our own empirical analyses of hundreds of markets as well as project collaboration with the Boston Consulting Group support the foundational premises of the Global Rule of Three.28 The world has changed so much, yet the Global Rule of Three prevails. So what exactly is the Global Rule of Three?

The Rule of Three and Globalization

Artificial market structures outside Europe and North America are also giving way to the “natural” market structure represented by the Rule of Three. For example, the great trading houses of Japan (such as Mitsubishi , Mitsui, and Sumitomo) have long participated in numerous business sectors, supporting weaker businesses through interlocking shareholdings (the “keiretsu” system, which creates a closed market within the overall free market). This shielded many poor performing companies from market forces, and as a result kept too many weak companies afloat in the market. In recent times, however, this system has finally started to break down. The discipline of a truly market-driven economy is forcing weak companies to exit or get acquired, often by global competitors .

In South Korea, the huge diversified “chaebol” such as Hyundai, Daewoo, Samsung, and LG have traditionally used their enormous clout with the government to maintain their leadership in virtually every major economic sector. The Asian economic crisis of 1997 and the conditions of the subsequent International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout of South Korea started the process of breaking down this cozy relationship and brought market forces to bear to a greater extent.

In India, most major industries have been dominated by the large industrial houses, many of them family-controlled. Two decades ago, foreign companies faced stringent restrictions on their ability to participate in the Indian economy. Capacity rationalization was nearly impossible to achieve as a result of licensing and the inability to “downsize” (reduce the labor force) when market conditions so dictated. All of this has changed, as economic liberalization and the demise of isolationist economic thinking have triggered a shift toward competitive markets.

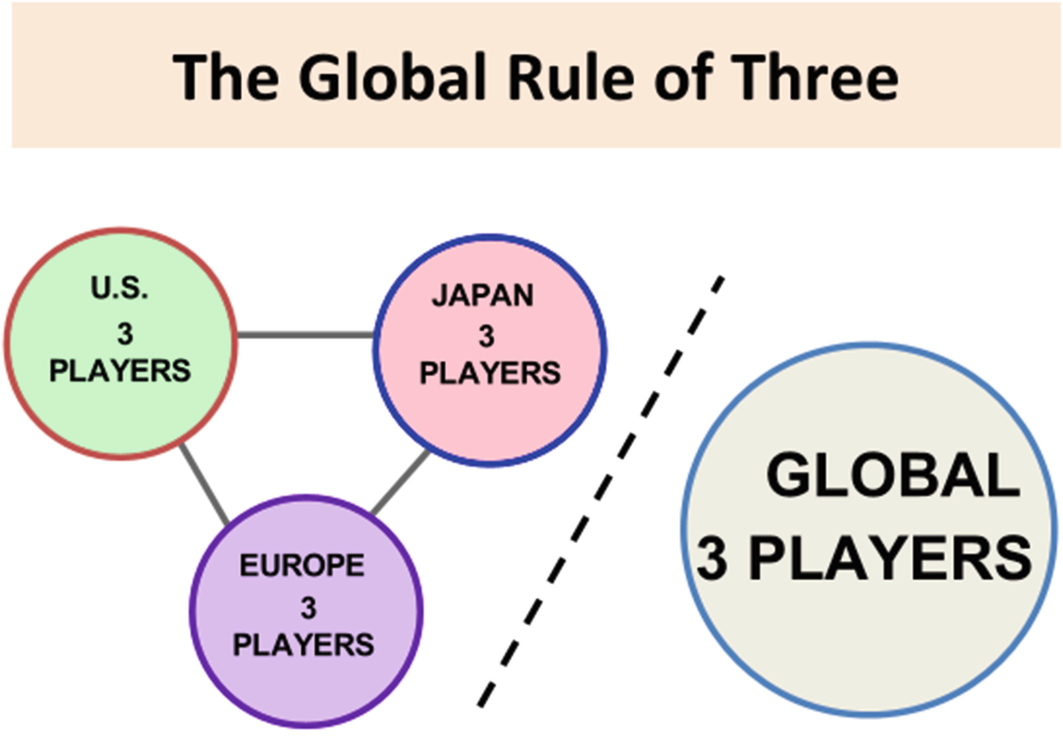

The important and ongoing shift toward global markets leads to a significant corollary of the Rule of Three: no matter how large the market, the Rule of Three prevails. In other words, when the scope of a market expands—whether from local to regional, regional to national, or national to global—the Rule of Three prevails, and further consolidation and industry restructuring become inevitable. Many nationally or regionally dominant companies find themselves trailing badly once the market globalizes.

For example, though U.S. banks are still prohibited from true, no-holds-barred interstate banking, they are working around those restrictions with holding company structures making de facto regional banking increasingly the norm. Consolidation through mergers and acquisitions is proceeding apace toward a Rule of Three market structure. Such a structure already exists in Germany and Switzerland. Likewise, the U.S. airline market has moved from a regional to national scope, and the process of sorting out full-line players from geographic specialists has been underway. The survivors are American, United, and Delta. Cable TV franchises, once the most local type of business, have consolidated into large regional players, with national and international consolidation following close behind.

Because local or regional markets are relatively rare (and are usually maintained only through regulatory mandate), the most important transition is when a market organized on a country-by-country basis moves toward becoming truly global. A distinct pattern emerges when markets move to this level, offering some of the most powerful evidence for the Rule of Three.

When the market globalizes, many full-line generalists that were previously viable as such in their secure home markets are unable to repeat that success in a global context. When this happens, we usually find that there are three survivors globally—typically, but not necessarily, one from each of the three major economic zones of the world: North America, Western Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region (also see Chap. 6 on the New Global Triad). To survive as a global full-line generalist , a company has to be strong in at least two of the three legs of this triad.

If a country has a large stake in an industry, it may be home to two or even all three full-line players. This was true in the aerospace market in the U.S., where the Defense Department essentially bankrolled the industry’s technological superiority. Japan targeted industries such as consumer electronics, steel, shipbuilding, and several others. In the long run, however, political considerations make it unlikely that one country could dominate a significant market globally. Thus, in the aerospace market, the historical dominance by U.S. companies led several European governments to boost Airbus to a position of global prominence.

With globalization, the #1 company in each of the three triad markets is best positioned to survive as a global full-line generalist. Other players either go through mergers as a consequence of global consolidation or selectively exit certain businesses to become product or market specialists, often by geographic region.

However, in the U.S. consumer electronics market, where not a single U.S. generalist has survived, a fierce fight for market share is taking place where the Koreans (Samsung/LG) have pushed aside the Japanese (Matsushita/Panasonic and Sony). This battle will determine which players survive as global full-line generalists . The U.S. presents an ideal battleground because there is no company with a “home court advantage”; since there is no major domestic consumer electronics player, there is little danger of government intervention. Ultimately, however, the Chinese may take over the U.S. market from the Koreans.

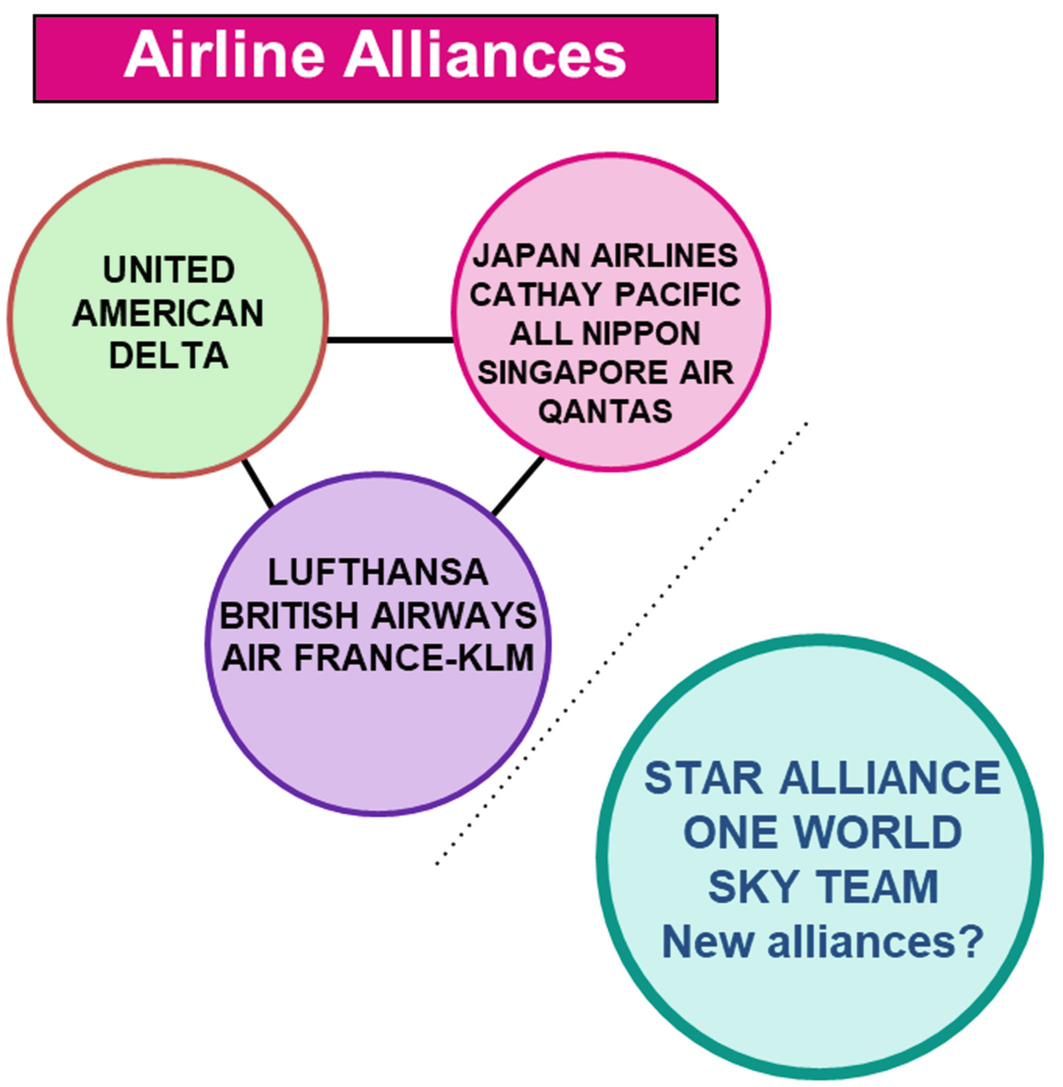

In the airline market, globalization is proceeding simultaneously with the market’s evolution toward national competition after deregulation. Given the numerous restrictions on foreign ownership of airlines, and in the absence of true “open skies” competition, the global industry is organizing into three big alliances: Star Alliance (Air Canada, Lufthansa, SAS, Turkish, United Airlines, and several others; 24% share), SkyTeam (Delta, Air France, Aeromexico, Alitalia, CSA Czech Airlines, and Korean Air Lines; 21% share), and Oneworld (Aer Lingus, American Airlines, British Airways, Cathay Pacific, Finnair, Iberia, LanChile, and Qantas; 18% share).29

From local to regional to national markets, the last stop in the evolution of industries and markets is going global, where three players eventually emerge globally and become dominant. “Globalization cannot be stopped, and there will be winners and losers in the transformation to a global marketplace.”30 A national market leader must have a strong foothold in at least two out of the three largest markets to become a global leader. As powerfully argued by Kenichi Ohmae in his seminal work on Triad Power, these three major markets were North America, Europe, and Japan historically.31

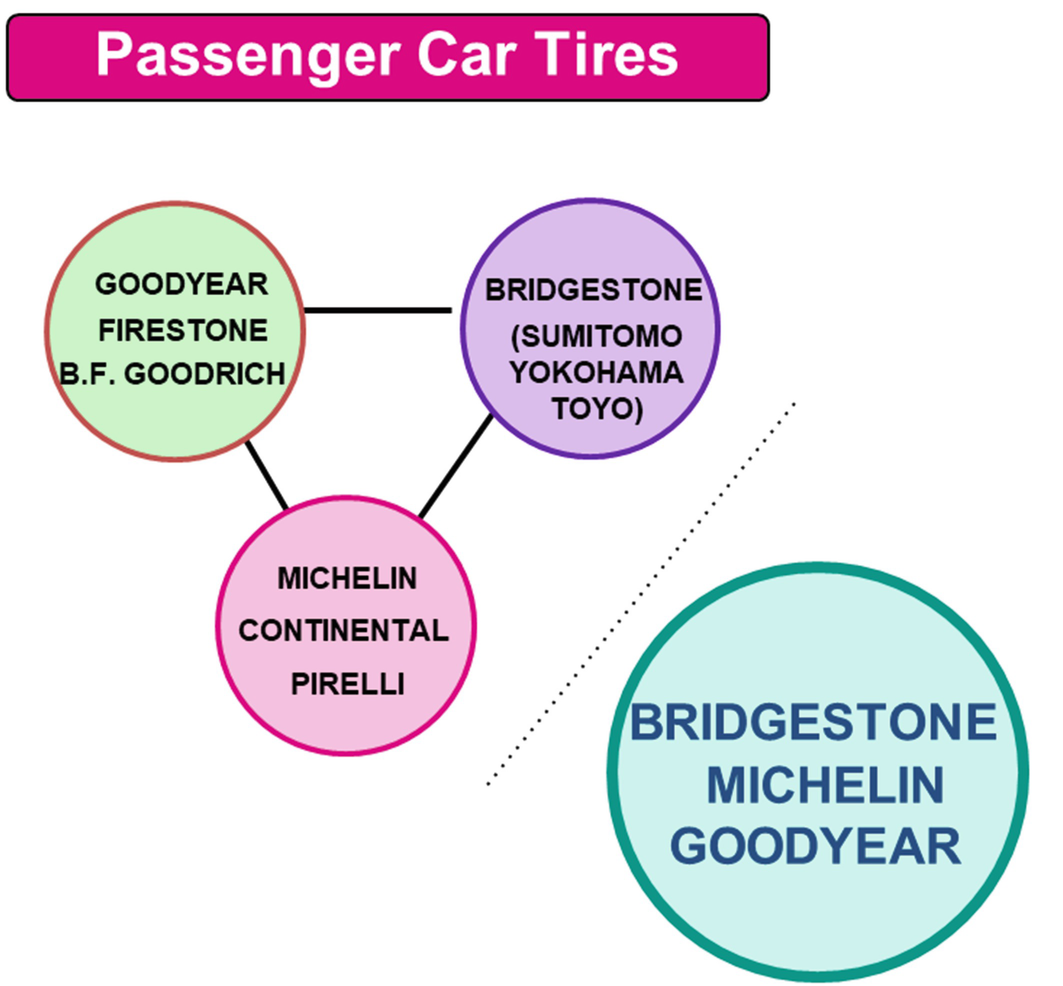

If the competitive process has already enabled the Rule of Three to apply in each of the three largest markets, then one player may rise as a global Rule of Three player from each market. We observe this most clearly in the global tire industry. The historical order in the U.S. was Goodyear, Firestone, and BF Goodrich (with Uniroyal and General Tire as specialists); Michelin, Dunlop, and Pirelli in Europe (and Continental since the EU had still not integrated, thus regulation allowed for the persistence of a fourth player); and Bridgestone, Toyo, and Yokohama in Japan. Then the world market became standardized through radial tires. Currently, Bridgestone, Michelin, and Goodyear make the top three players in the world and the Rule of Three has prevailed globally as well.

On the other hand, a great deal of change is taking place and the global leaderboards are far from immune. Indeed, a new triad power has emerged, making it increasingly unlikely that one player from North America, Europe, and Japan each will continue to prevail as global leaders. On the contrary, the global leaders of the twenty-first century will increasingly arise from emerging markets. For example, Apple, once the disrupter and global leader of smartphones, vacated the #1 position to Samsung and was then surpassed by Huawei from China.32

Similarly, global PC manufacturing incumbent HP has been surpassed by Lenovo. And if you guessed the global leader in a legacy industry such as the tobacco market is Philip Morris or British-American Tobacco, you’d be wrong. China National Tobacco Corporation is the global leader with a 32% global market share that dwarfs Philip Morris’ 15% and British-American Tobacco’s 16%, respectively.33 Finally, all three of the most valuable banks in the world (namely ICBC, China Construction Bank, and Agricultural Bank of China) hail from China measured by brand value or assets.34 The center of gravity is clearly shifting from the West to the East, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Why and how did we get here?

In many ways, the notion of shifting economic powers and the commensurate rise of nations is nothing new. For example, South Korea took leadership in a number of industries such as steel, appliances, and telecom. Before South Korea, the economic miracle story was Japan, whose firms took leadership from their European and American counterparts in a number of industries such as automobiles, robotics, and consumer electronics. And even before then, Americans were aggressively conquering markets from European incumbents. Thus, the European Century (nineteenth) gave way to the American Century (twentieth) and now the twenty-first century clearly seems to belong to Asia. And China and, as we will discuss in Chap. 6, India are taking full advantage.

Liberal policies tend to bring prosperity and accelerate the transfer of wealth, whereas protectionist policies try hard but fail to stop it. Taking a historical view, it is important to recognize that openness and increasing trade permeated across the globe during the late nineteenth century. Unfortunately, the rise of nationalism and two World Wars prevented the natural evolution of free trade until the second half of the twentieth century. Subsequent to World War II, there was a period of time where several world leaders emphasized self-sufficiency through tariff and non-tariff barriers rather than building comparative advantages based upon the natural as well as human resources of their countries. However, protectionism threatened the affluence of both developed and developing nations.35 When it became all too obvious that these approaches did not work, globalization resumed its inevitable path to prominence.36 The volume of trade between and among the NAFTA countries, EU, and ASEAN has been increasing since the 1980s as a result of trade liberalization. After the collapse of communism, economic pragmatism became prevalent; privatization unlocked value for consumers and investors and accelerated this process. Tariffs were decreased. New innovations in communication, increased travel, internet, and advertising also led to a higher acceptance of foreign-origin products and services. “Consumers came to appreciate diversity and variety in the marketplace. Turkish doner became the most consumed fast-food in Germany, Indian curry became the flavor of choice in England. Salsa sells more than ketchup in the US….”37

Globalization also has cultural, social, and humane implications. Cultural diversity is our human heritage. Arguably, the single most important source of economic as well as scientific development has been based on trade between nations (with varying resource advantages). “However, nations do not trade, merchants do. These merchants not only generated financial wealth, but also served as a bridge for new inventions, social innovations, and culture. For example, pasta as well as gunpowder found their way to Europe through trade…Merchants of today are increasingly global corporations,”38 and the world is a “global shopping center” with an autonomous economy which is more than the sum of national economies.39 In this context, global competitiveness is the new institutional imperative for corporations.40

It is fair to say that whereas the twentieth-century business was based primarily on ideology, politics, and advanced nations, the twenty-first century will be primarily based on markets and resources of emerging nations.41 Akin to the emergence of three players in each cycle from local to regional to national, the convergence to the Global Rule of Three is also economics driven. To the extent that deregulation (open competition) accelerates the national Rule of Three, low barriers to trade and free markets accelerate the convergence to the Global Rule of Three. Our position is that the reach of globalization is irrevocable. Hence, no matter how much protectionist policies get in the way of progress, a global convergence is also ultimately inevitable. And when the industry globalizes, there is no room for more than three players, in the long run, no matter how big the companies.

In the next section, we trace the evolution of global markets and examine which multinational corporations might emerge as the top players.

2019 GDP indexed to purchasing power parity (PPP)

China | $27.31 trillion |

U.S. | $21.43 trillion |

India | $11.04 trillion |

Japan | $5.71 trillion |

Germany | $4.44 trillion |

Russia | $4.39 trillion |

Indonesia | $3.74 trillion |

Brazil | $3.48 trillion |

U.K. | $3.16 trillion |

France | $3.06 trillion |

In a global economy, multinational corporations play a significant role in the transfer of wealth between regions and nations. Margin expectations at the stock exchanges of advanced economies lead the incumbents to divest or vacate commoditized segments and businesses. This trend has favored Asian firms. As markets are vacated by incumbents, we expect to see China become #1 or #2 globally in an increasing number of industries. In that sense, the center of gravity of the Global Rule of Three is shifting from the U.S. and Europe to Asia, and from Japan and Korea to China and India. There will inevitably be more consolidation as well as newly emerging players in the global arena. For example, Japan has already conceded the shipbuilding sector to South Korea. Meanwhile, Hanjin Shipping Company, South Korea’s largest shipping line, and one of the largest container carriers in the world went bankrupt in February 2017.43 We predict that the Chinese shipping firms will rise to further prominence to challenge Danish shipping giant Maersk in the future.

Transition from Local to Regional to Continental to Global

Businesses that used to compete locally can become regional with government blessing. For example, the U.S. banking sector used to be local within each State. Consolidation followed gradual deregulation and the Rule of Three became prevalent at the regional level on both East and West Coasts. Currently, Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase, and Wells Fargo all have more than 10% share and are jockeying for position.44 Meanwhile, regional banks are trying to scale up as evidenced by the recent merger of BB&T and SunTrust valued at $66 billion.45 While Uber and Airbnb both started as local operations in San Francisco and have become global network empires, most hospital groups, universities, and colleges are still local, and many utilities are still run as local monopolies.

Open markets lead to rationalization and a continental Rule of Three structure. Currently, the airline industry is transitioning from national to regional/continental, and regional economies such as the EU and ASEAN facilitate this transition. Despite the potential impact of Brexit, German, French, or Italian markets cannot be conceived independently of another.

Meanwhile, some of the most fascinating journeys take place when industries transition from regional/continental to global. This transition to global markets can be attributed to the following factors:

New market opportunities: Globalization of markets can come about based on new market opportunities. For example, U.S. companies became increasingly global after WWII to revitalize the destroyed infrastructure and economies of Japan and Europe through the Marshall plan “which was geared to build a market for U.S. goods and private sector open to U.S. investment.…”46 U.S. businesses were motivated by the government to enter these foreign markets and invest; the rest is history. IBM, Coca-Cola, Boeing, McDonnell-Douglas, Lockheed, and Johnson Controls all became dominant players globally, beginning with the Japanese market.

Liberalization of trade: The old model used to be about starting and getting established domestically first, and subsequently using the cash flow from domestic operations to fund/subsidize gradual international expansion. The typical evolution took place through joint ventures because foreign acquisitions were blocked through formal and informal mechanisms. For example, Xerox had joint ventures with Fuji (Japan), and Rank (U.K.). However, the energy crisis and the subsequent sluggish economic conditions in the 1970s gave way to rise of free markets in the 1980s and 1990s. Western economies were not growing domestically while emerging markets needed machinery and capital, so foreign trade and operations were encouraged. Globalization accelerated as large emerging economies came to the realization that they could not survive on their ideologies alone; be it communism in the Soviet Bloc, socialism in India, or China where a doctrinaire communist regime proved unsustainable and needed to be reformed. Latin America went through a similar process. Thus, the European Union was founded (1993), NAFTA was signed (1994), the GATT was folded into the WTO (1995), and the ASEAN bloc was expanded—all in the 1990s. It was thanks to this liberalization of trade that the multinational corporations of the West were eventually allowed to buy out the stakes of their joint venture partners, and integrate their foreign subsidiaries with their domestic operations .

Private sector participation: Nowadays , governments around the world permit and even encourage the private sector to participate in new market opportunities. For example, the richest person in Latin America (and fifth in the world) is Carlos Slim, thanks primarily to his telecom empire enabled by the Mexican government (a consortium led by Slim’s Grupo Carso bought Telmex, the old government monopoly, when it was privatized in 1990 and made big bets in wireless telecommunications).47 Similarly, almost 100 Russian oligarchs accumulated a wealth of more than $1 billion each following the privatization that took place after the collapse of communism.48 Billionaires came out of nowhere in emerging markets such as China, India, Brazil, Mexico, and Turkey, and formed conglomerates. And then as a natural next step, these conglomerates from emerging markets also started going global (also see Chap. 7).

Globally conceived tech firms: Globalization has also been accelerated by born-global technology companies who think about global leadership from day one. The classic example of this phenomenon is Microsoft whose operating system became dominant globally well-within a decade of the company’s inception in 1975. Indeed, its first international office, Microsoft Japan (named ASCII Microsoft at the time) was founded in 1978, two years before the company’s famous deal to develop the operating system for the IBM PC.49 Similarly, Apple (founded in 1976) had its first authorized dealer in Japan in 197750 and always capitalized on the potential of global markets for each of its products from then on. Google search engine was designed to serve consumers globally from the get-go, and Facebook with its 2.7 billion users is also clearly a global player.51 Naturally, the revenues of these global tech giants are also commensurate with the size and number of the markets served. Silicon Valley is full of start-ups with global aspirations. The new breed of tech firms (e.g., Snapchat and Twitter) was all born global. For example, Airbnb had over 4 million listings in some 65,000 cities across 191 countries in 2018.52

However, the born-global business is not unique to the U.S. In fact, born-global firms are more likely to come out of countries with limited home market potential such as Estonia (population 1.33 million; Skype), Sweden (pop. 10.23 million; IKEA), Finland (pop. 5.52 million; Nokia), or Israel (pop. 8.88 million; M-Systems) which ranks #1 for R&D intensity in the world and has also been dubbed the Startup Nation.53

Based on the above factors which underline and fuel globalization, several consequences are to be expected:

Domestic Consolidation: The influx of new competitors further necessitates the need to build efficiency and cause within-border mergers of equals. Historically, we have witnessed intensive consolidation among the airlines following deregulation (and the entry of new low-cost carriers). GE’s acquisition of RCA and the HP-Compaq merger are additional examples of this phenomenon. Current examples can be found in the financial (e.g., SunTrust-BB&T merger) and pharmaceutical sectors (e.g., BMS Celgene acquisition).

Global Consolidation: As companies expand globally, they tend to enjoy scale and scope which comes from adding multiple product lines, and adding new geographies. However, as markets grow from local to regional, regional to national, national to continental, and ultimately global, industries consolidate further. The evolution in consumer electronics is reflective of this. For example, top PC manufacturers have already become global, and we predict no survivors from the U.S. in the future. Lenovo will be #1, and Acer will likely become global #2. Perennial leader IBM years ago exited the business by selling to Lenovo, and the future for other household names such as HP and Dell does not look bright. A similar pattern is taking place in the world of television; U.S. companies exited during the early 1980s because they could not compete with Japanese, and the Japanese now find it hard to compete with the Koreans, who will not be able to compete against the Chinese! The same pattern also applies to IT infrastructure manufacturers in the evolution to a global structure. The Alcatel-Lucent merger (2006) and Nokia’s acquisition of Alcatel-Lucent (2016) are further examples of this enormous surge in global M&A with no end in sight.

Restructuring of Survivors: If a generalist is strong in all three triad markets, it will survive. In fact, strength in only two of the three markets is frequently sufficient for survival. Since Asia is proving a challenge for global telecom giants, they have been trying their hands in the relatively neutral U.S. While Deutsche Telecom has held onto its 3# position in the U.S. with T-Mobile, Vodafone, the second-largest mobile operator in the world, was bought out of its 45% stake in Verizon Wireless for $130 billion in 2013.54 In the final analysis, there is only room for three global players, and some leaders will either be acquired or must give up their generalist status, abandon certain markets, and become niche players. For example, recall the example of The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company a.k.a. A&P discussed previously. Once a leading supermarket chain, A&P had to change its business model, abandon markets, and become a niche company in order to exit the ditch .

Major Investment in Emerging Markets: In most cases, these investments already have to be completed in order to remain ahead of the curve. Arguably, General Motors (GM) is surviving today because of its early foray into the Chinese market. Even though GM exited China in 1949 and re-entered with a joint venture in 1994, its presence dates back almost a century. In fact, there was a Chevy dealer in Shanghai as early as the 1920s, and Sun Yatsen, who is recognized as the father of Chinese democracy, the first premier Zhou Enlai, and the last emperor Puyi all owned Buicks. Reportedly, over 15% of the cars in China in the 1930s were Buicks. Not surprisingly, Buick continues to do well in China .55

Similarly, Volkswagen started initial negotiations for entering China in the 1970s and has had a presence for almost four decades.56 L’Oréal, with over 20 years of experience in China, also boasts a headquarters, R&D center, two plants, and four business divisions there and has clearly benefited from the tremendous growth of its economy over the last two decades.57 The future of L’Oréal and many luxury brands increasingly lies with China, and it is increasingly apparent that beauty can even overcome trade wars, as sales of Lancôme and Yves Saint Laurent Beauté continue to rise regardless of the economic sub-text.58

Most accounting, law, and consultancy firms are private. They are based on a partnership structure where owners are also the managers, whereas ownership in public firms is divorced from management. Nevertheless, the journey to Rule of Three commences whenever the partnership structure is abandoned. For example, advertising agencies were historically founder-driven. Subsequently, leading agencies such as Ogilvy, Leo Burnett, and Young & Rubicam decided to divest ownership and create groups. Hundreds of agencies have consolidated, and a big four (Omnicom, WPP, Publicis, and Interpublic) have emerged globally.59 Indeed, if the 2014 Publicis Omnicom merger deal had not collapsed, we would have already observed the Rule of Three in this historically fragmented industry.

The journey for accounting firms has been somewhat different. There used to be eight large accounting firms which have since consolidated into the big four (Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers or PwC, Ernst & Young or EY, KPMG). Smaller accounting firms such as BDO, Grant Thornton, and CliftonLarsonAllen continue to consolidate further. However, as long as they remain partnerships, the Rule of Three structure may not be realized. Interestingly, their primary competitors in IT consulting, such as IBM and EDS, were already publicly traded. Thus, the big four decided that traditional accounting such as audit, advisory, restructuring, and tax could remain partner-driven whereas the consulting side could be divested or publicly traded. For example, EY sold its IT consulting to Capgemini and PwC sold it to IBM, both of which are publicly traded. Deloitte and KPMG may similarly decide to divest. Interestingly, there were internal fights within Andersen as to which group would keep the Andersen name which ironically became a liability following the Enron scandal; thus, the consulting practice was rebranded as Accenture. The main reason for this structural transformation is that partnerships are unable to utilize stock options the way they are utilized by publicly traded firms to reward employees. This creates a competitive disadvantage. Typically, the Rule of Three goes in tandem with going public. Indeed, it is rare for private firms to prevail as global contenders.

If a global player somehow misses the boat, it is compelled to make major acquisitions in emerging markets in order to survive as a global player. Besides China, which now boasts many global brands such as Haier, many emerging nations have developed their own dominant brands. Investing in emerging markets represents both an offensive and defensive play: multinational corporations from emerging markets are rising to prominence globally; hence, the incumbent multinationals must scramble to equalize.

For example, Uber (which recently bought Middle Eastern start-up Careem for $3.1 billion),60 is competing with Didi from China rather than Lyft from the U.S. for global dominance.

Similarly, Starbucks has been in China for two decades with over 4000 outlets in 140 cities, but now finds itself in competition with Luckin Coffee which is three years old but has already surpassed Starbucks with over 4500 locations across China. In response, Starbucks plans to expand to 6000 locations by 2022.61 Similar battles have played out in India as well. For example, after Coca-Cola was forced out of India in the 1970s, local soda brands such as Thums Up, Campa Cola, and Limca thrived. When Coca-Cola returned to India in the 1990s, it found that Thums Up did better than the original Coke and wisely decided to keep the brand they purchased. Today, Thums Up is the #2 selling soda brand in India after Sprite.62

Besides China and India, the key emerging markets that require presence by all global players differ based on sector. For example, Brazil is key for agriculture, industrial raw materials, and construction equipment. For global players with foresight (e.g., Huawei), African nations represent the current frontier for infrastructure investments.

- U.S.:

three big players + niche players

- Europe:

three Players (primarily Western Europe), one German, one French, one Italian/Dutch/British, and so on + niche players.

- Japan :

three big players (Japan used to be second-largest economy, now is the fourth) + niche players

The Global Rule of Three circa 2000. (Source: Adapted from “The Global Rule of Three” presentation by Jagdish N. Sheth, 2017)

Mega-mergers such as AOL-Time Warner and now AT&T and Time Warner continue to increase in size and frequency, delighting investment bankers. However, beyond 40% domestic market share, the incremental value generated by the market leader starts to diminish and there are greater incentives to engaging in international market development. Yet no matter how big the market, there is simply not enough room for nine top players globally. Thus, another round of consolidation takes place, this time in the form of cross-border M&A, until the leading player assumes a viable share of the global market. The mergers that have been taking place are not only within countries but between regions. For example, there is tremendous activity in global M&A and exits in the steel industry, carbon black, aluminum, cellular phones, and so forth. In the end, we fully expect to see the emergence of the Global Rule of Three in each of these sectors.63

We proceed now with additional examples of global industries and then discuss the evolution in greater depth.

The Case of the Tire Industry

Consider the global automotive tire industry. As you may recall, this is an example of a structure where the large players are balanced among the three markets. That is, there are established incumbents in each of the key markets. Interestingly, when there are three established players in each key market, one (usually #1) out of each market becomes a global leader, and #3 players become the first casualties as industries become global. As foreign firms enter, competition becomes too intense and the #3 firm collapses trying to fight for market share. For example, Dunlop was acquired by Goodyear under distress, and BF Goodrich sold to Michelin. (There was no #2 or #3 at the time in Japan.)

The industry started globalizing in the 1970s. Michelin capitalized on the success of its radial tires and opened a manufacturing plant in the U.S. in 1975. As the U.S. manufacturers were trying to catch up or exiting, Michelin was acquiring companies in the U.S., Poland, Hungary, and Colombia in the 1980s and eventually became the global leader. However, Bridgestone of Japan also had leadership aspirations. It outbid Pirelli to acquire Firestone (then the #2 player in the U.S., which also had a European presence) in 1988 and subsequently became the global leader. Finally, Goodyear was not able to hold onto its market leadership in the U.S. and is currently the #3 player globally. Thus, the global big three consists of #1 Bridgestone, #2 Michelin, and #3 Goodyear.

- U.S.:

Goodyear-Firestone-BF Goodrich (see Box 5.2 on BF Goodrich for an illustrative example of dealing with an intensively competitive market structure).

- Japan :

Bridgestone (it was the only player historically but now has three more competitors, Sumitomo, Yokohama, and Toyo).

- Europe:

Michelin-Continental-Pirelli

Global passenger car tires. (Source: Adapted from “The Global Rule of Three” presentation by Jagdish N. Sheth, 2017)

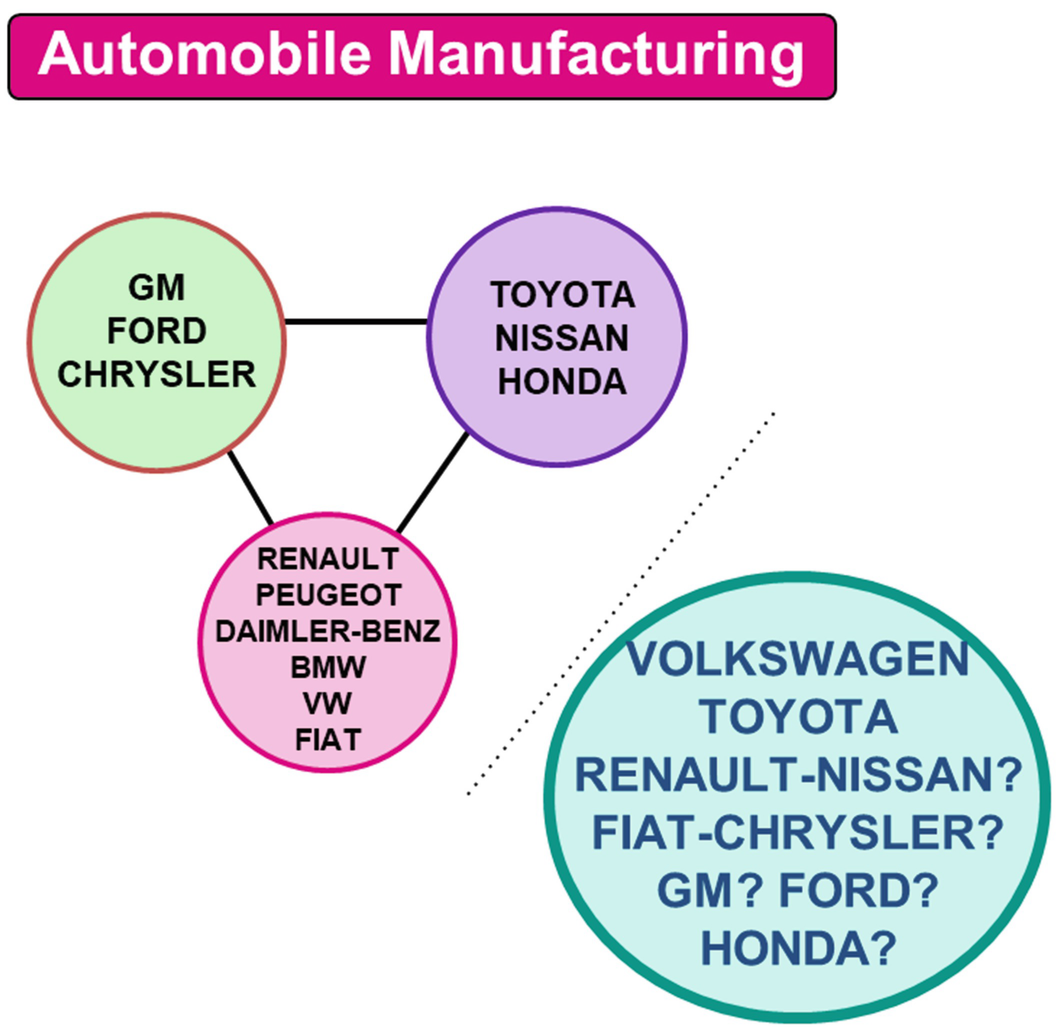

The Case of the Automobile Industry

The evolution of the U.S. automobile industry is illustrative of the predictive power of the Rule of Three. During its early days, the industry’s facilities consisted of workshops. By 1914, over 300, mostly small, automakers had set up shop. By the 1940s, however, the maturing industry was consolidating to three front-runners, GM, Ford, and Chrysler, alongside small specialists such as American Motors Corporation (AMC) and Studebaker. The structure provided stability over the next couple of decades. However, the industry was disrupted by the Japanese market entry with smaller reliable cars, and subsequently the fuel crisis. Toyota (and for a while Honda) became strong competitors. Consequently, when the competition for market share between GM and Ford intensified, the number three incumbent Chrysler succumbed to the ditch at the end of the 1970s. Its revival required not only CEO Lee Iacocca’s exemplary leadership but also the biggest government bailout to date in 1979. When the government’s shot-in-the-arm subsided, Chrysler once again attempted to exit the ditch by purchasing AMC in 1987.

AMC was another ditch dweller which had downsized to a specialist and acquired earlier in the decade by Renault. However, the structural problem in the market (i.e., Japanese competition) persisted, so struggling Chrysler tried a third time to get out of the ditch by merging with Daimler in 1998. This, in light of the Rule of Three, was bound to fail yet again because Daimler is a specialist in the U.S., and the combined shares of the two still left the Daimler-Chrysler combo stuck in the ditch with the wrong size. Moreover, differences in corporate culture between the two companies proved too much to bear. Finally, facing a global financial crisis, and once again rising fuel prices, the U.S. automobile industry experienced peril in the new millennium. In 2008, both Chrysler and GM had to be bailed out by the government.

Left to market forces, Toyota, Ford, and a nimble, restructured, and divested GM would likely have prevailed as the new big three in America. With cash infusion from Fiat, Chrysler temporarily overcame the ditch hurdle by improving its share from 8.9% to 11.5%.66 Whether the new products and technology from Fiat’s platforms will succeed in keeping them on the right side of the fence remains to be seen. Historically, Chrysler had, and still has, the option to survive as a specialist or get acquired by one of the top three. It appears that every ten years or so, structural problems surface and something has to give in the U.S. automobile industry.

Globally, the question remains as to who will be the #3 player behind Volkswagen and Toyota. Superniche players like Ferrari and Lamborghini will remain. In fact, Ferrari’s annual volume of roughly 10,000 sports cars gave it a market cap of $29.8 billion in May 2020 which exceeded that of GM, Ford, or Fiat Chrysler.67 However, volume-driven players will have problems, and casualties are expected to occur in Europe and Japan. What will happen to smaller players such as Honda, Nissan, and BMW? One can speculate that downsizing and specializing would be more suitable for BMW than Honda. Thus, Honda could become casualty, yet it has traditional pockets of strength for building engines for other applications to fall back on. Nissan, which has already been bailed out by Renault previously could be headed for bigger trouble.

Meanwhile, the entire deck is being reshuffled with Germany vowing to stop production of internal combustion engines by 2030!68 Who will dominate the electric cars in the new world order? Tesla is very innovative yet remains undercapitalized and its stock is among the most shorted in history.69

And do not count out latecomers such as China’s Geely, which sold more than 1.5 million vehicles in 2018.70 Another shakeout appears to be on the horizon and we will surely see more M&A activity in this space in the next decade. When there are two global players, a third one emerges sooner or later, usually through M&A or alliances. No wonder Fiat Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne has been trying to talk GM into a merger for years.71 As the reported aspirations of Peugeot to buy Fiat Chrysler, and the plans of Renault to buy both Nissan and then Fiat Chrysler demonstrates, the push for global consolidation will remain quite strong in the automotive industry.72 Meanwhile, Ford is focusing on trucks to boost its profitability and may even exit the four-door sedan market one day.

- U.S.:

GM-Ford-Chrysler

- Japan:

Toyota-Nissan-Honda

- Europe:

Volkswagen-Renault-Fiat-Daimler Benz-BMW

Global auto manufacturers. (Source: Adapted from “The Global Rule of Three” presentation by Jagdish N. Sheth, 2017)

While you may be familiar with Goodyear, Bridgestone, or Michelin, you are probably not as familiar with BF Goodrich, unless you are an auto enthusiast. It may also come as a surprise that BF Goodrich is the oldest and arguably the most innovative tire manufacturer in the U.S. It is illuminating to review its storied history.

BF Goodrich was founded by Dr. Benjamin Franklin Goodrich in 1870 in Akron, Ohio, a city that would come be to known as the rubber capital of the U.S. (Goodyear as well as several other tire manufacturers would be later based there). Its first products included fire-hoses covered with cotton and later on bicycle tires. The company quickly thrived and became one of the largest rubber and tire manufacturers in the world.

BF Goodrich was decidedly innovative from the start. It established a rubber research laboratory in 1895, the first of its kind in the U.S. The company also became one of the earliest suppliers of tires and other equipment to airplanes. BF Goodrich was proud to let the public know that the winner of the inaugural international flying race in 1909, as well as Charles Lindbergh when he flew solo from New York to Paris for the first time in 1927, had BF Goodrich tires on their airplanes. The R&D engine of BF Goodrich churned out one great invention after another. For example, the rubber reclamation process that BF Goodrich developed was widely adopted by the industry and utilized for decades.

More important, BF Goodrich invented the PVC (polyvinyl chloride) in 1926. PVC went on to have a number of very successful applications such as floor covering, electrical insulation, garden hoses, and luggage. Charles Lindbergh had commented that ice was the biggest danger he faced on his historic flight across the Atlantic. BF Goodrich developed and introduced the first aircraft de-icing mechanism in 1932 to address the problem.

The company focused on two areas of specialty to build upon its expertise in rubber manufacturing—specialty chemicals and aerospace. The specialty chemicals focus was in part based upon the need to improve the characteristics of rubber products, which the customers demanded. Similarly, the focus on aerospace was initially limited to supplying tires and rubber products to planes but consequently expanded to military applications.

In 1938, and just in time for World War II, BF Goodrich invented synthetic rubber and scaled-up production. This invention turned out to be critical for the U.S. war effort since as much as 95% of the production relied on the natural rubber supplies from the Far East. Since Japan controlled the trading routes, the U.S. would have lost much of its mobility without BF Goodrich’s synthetic rubber.

In 1946, BF Goodrich invented the tubeless tire which represented another breakthrough innovation for the industry. Whereas tires with tubes were more likely to blow out due to friction, the new tubeless tires had airtight seals, resulting in significantly better tire safety.

After World War II, BF Goodrich developed a new strategy for a peace-time economy. It began to diversify and expand its presence in the aircraft industry via acquisitions. Aerospace became an independent division within the organization in 1956. The fuel controls of the first jet airliners were provided by none other than BF Goodrich. Even astronauts are familiar with the brand BF Goodrich. To develop its first spacesuit, NASA commissioned the company in 1961. During the cold war era, BF Goodrich continued its investments in emerging technologies such as surveillance, reconnaissance, space, and aviation technologies.

Tire Industry Evolution

The bread-and-butter tire business which accounted for 60% of BF Goodrich’s revenues was getting more and more competitive. The company was struggling to remain among the top three players and prevent succumbing to the ditch. Many of the new innovations (such as tubeless tires) served to extend the usable life of the tires which meant fewer replacement tire sales and more intense competition for the original equipment manufacturer (OEM ) tire business (i.e., tires installed on new cars by their makers). This point was brought home by William O’Neil Sr., who founded General Tire: “Detroit wants tires that are round, black, and cheap-and it don’t care whether they are round and black.”74 In the 1960s, while the replacement tire market profit margin ranged between 5% and 8%, it was merely 3–5% for the OEM market.

In 1979, BF Goodrich’s world market share was about 4% against 23% for Goodyear, 16% for Michelin, 14% for Firestone, 7% for Bridgestone, and 6% for Pirelli. The historical focus of BF Goodrich was the replacement tire market which represented about three-quarters of the tires sold. Again, about three-quarters of these tires were typically bought for passenger cars. For example, in 1987, of the 205 million tires sold, 152 million were replacement tires and 53 million were OEM tires.

Worldwide production exceeded 800 million tires in the late 1980s. The market was more or less divided between North America (30%), Asia (30%), and Europe (25%). Benefiting from the success of their steel belt radial tires, Michelin from France became the largest manufacturer, followed by Goodyear (U.S.), and Bridgestone (Japan).

The Move to Radial Tires

Radial tires were commercially introduced by Michelin in 1948 and made popular in Europe. Nevertheless, they were not immediately successful in the U.S. By 1970, 97% of tires sold in France, and 80% of tires sold in Italy were radial, whereas they represented merely 2% of sales in the U.S. Radial tires required automobiles to have an updated suspension system. They also cost about 35% more to produce and resulted in a harder ride. In 1971, the CEO of General Motors declared that “[y]ou won’t see a changeover to radial tires as original equipment on Detroit’s new cars in the near future.” And yet radial OEM orders started to come in by Fall 1972.

Goodyear initially questioned the new technology but subsequently introduced its own all-season radial tire five years later in 1977. The incumbents also made efforts to upgrade to advanced bias ply with steel belts (belted bias ply). Among these, Firestone made significant investments but failed to merge radials to existing bias-ply system and maintain product quality. Subsequently, they agreed to a voluntary recall of 8.7 million tires in 1978 at a cost of $150 million, which amounted to the largest product recall in U.S. history at the time.

The new radial technology provided longer product life, increased safety, handling, and economy than even the most expensive bias tires. For example, radial tires last three to four times longer than ply tires. However, producing radial tires required U.S. manufacturers to get new equipment such as tire building machines, fabric and wire bias-cutters, new or modified curing, slacking, and handling systems. Once again, it was BF Goodrich that first produced and sold radial tires to the American public in 1965. They also launched the “Radial Age” advertising campaign.

Michelin began making inroads to the U.S. market through its private branding deal with Sears and was selling one million tires annually. The tire industry was going global. Globalization required more R&D which was only sensible if the significant sum could be allocated over a larger number of units. For example, when Honda entered the U.S. market, Bridgestone brand tires followed them. As the fourth largest tire manufacturer in the U.S., BF Goodrich experienced some market share gains but was increasingly seeing its profit margins shrink.

The Aftermath

BF Goodrich recognized the structural problems, the inherently intensive competition, and the thin margins in the tire manufacturing business, and decided that their core competency of specialty chemicals was better deployed elsewhere, namely in the aerospace industry. First, their solution to the structural problem was to spin-off their tire division and strengthen it with a merger with Uniroyal 1986. Alas, the Uniroyal Goodrich generated close to $2 billion in revenue but merely $35 million in profits in 1987. Thus, it was welcome news when Michelin offered to buy the company in 1988 and completed the buyout for roughly $1.5 billion in 1990. The shrewd strategic move away from tires paid off, and BF Goodrich never looked back. In 2001, it divested its specialty chemicals division to focus on aerospace and related markets and changed its name to Goodrich Corporation. Eventually, it became the largest pure-play aerospace company in the world. In 2012, United Technologies acquired Goodrich in an $18.4 billion deal (additionally assuming another $1.9 billion in Goodrich debt obligations). Meanwhile, Goodyear which was the perennial market leader when Goodrich exited the tire business in 1990 had a market capitalization of merely $3.28 billion in 2012, just a fraction of what United Technologies paid for the Goodrich deal.

The Case of Aircraft Manufacturing

There was a time when the U.S. had a complete monopoly over aircraft manufacturing following the Wright brothers’ successful flight at Kitty Hawk. The old-world order used to be Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, and Lockheed. However, Lockheed lost billions in its transatlantic partnership with Rolls-Royce over a decade and its wide-body jet business collapsed in the early 1980s, so it decided to focus on military aircraft where margins were healthier.75

Europe’s joint Airbus consortium effort (supported by several governments) capitalized on the gap and became #2, effectively creating a global triad between Boeing, Airbus, and McDonnell Douglas. During an intensely competitive period between Boeing and Airbus during the 1990s, McDonnell Douglas found itself in the ditch. Airbus made its foray into the U.S. by leasing planes to failing airlines such as Continental, and Air Canada. Eventually, even American Airlines also bought from them, breaking the Boeing monopoly. After McDonnell Douglas’ efforts to create an alliance with Taiwan Aerospace were blocked by the U.S. government, it merged with Boeing in a $13.3 billion deal in 1997.76

Global aircraft manufacturers. (Source: Adapted from “The Global Rule of Three” presentation by Jagdish N. Sheth, 2017)

Post the United Technologies-Raytheon mega-merger, a wave of M&A appears to be on the horizon for the aerospace and defense industry in the next few years. We expect some players to act soon. Boeing needs to counterbalance its commercial market domination and 737 Max woes, and engine-maker GE Aviation could be the likely target. Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and to a lesser extent, Northrop Grumman will all suffer financially and get acquired if they do not actively seek mergers. Private equity has an increasingly large role to play in consolidating industries that are quickly becoming global (also see Box 8.1 “Why More Mergers Are Inevitable in Aerospace and Defense” in Chap. 8).

The Case of the Airline Industry/Alliances

The U.S. airline industry went through big-bang deregulation in 1978.78 The Civil Aeronautics Board was abolished, and regional franchises and price-controls were abandoned. Nearly 70 airlines collapsed in the race to grow and become national. For example, Allegheny (which was later renamed US Airways) bought Lake Central, Mohawk, Pacific Southwest, Piedmont, Trump Shuttle, Metrojet, and America West, and finally merged with American Airlines in 2015. Northwest and Continental both succumbed to the ditch and were acquired by Delta and United respectively. At the end of the journey, American, United, and Delta emerged as legacy carriers, until Southwest decided to become a national airline and disrupt the Rule of Three. Southwest is currently competing with American Airlines head-to-head for domestic market leadership. Meanwhile, Delta took advantage of its rival’s customer service woes and public relations blunders to dislodge United and become the #2 legacy carrier (#3 overall).79 A similar journey is still taking place in Europe. In fact, since October 2018, five European airlines have collapsed (Wow Air, Primera Air, Cobalt Airways, Germania, British Midland).80 Further consolidation looms large to the extent that antitrust policy permits it. And when it doesn’t, new alliances are forged.

Certain industries such as postal services, telecom, electric utilities, and airlines are subject to heavy government rules and regulations. Because of public sector ownership or antitrust concerns, companies may not be able to merge. Thus, they form alliances to which the Rule of Three also applies.

- U.S.:

American-Delta-United81

- Note:

Southwest Airlines has the lead in domestic passengers but is not interested in global expansion.

- Far East:

All Nippon-Singapore Air-Qantas

- Europe:

Lufthansa-British Airways-Air France

- Global Consortia:

Star Alliance-One World-SkyTeam

Global airline industry and alliances. (Source: Adapted from “The Global Rule of Three” presentation by Jagdish N. Sheth, 2017)

However, once again the global order is likely about to change. China, having observed the aftermath of the big-bang deregulation experience of the U.S. and seeing dozens of airlines go out of business decided to consolidate their airline operations and allow for only three major carriers (China Southern, China Eastern, and Air China) to exist in the first place. This enabled them to avoid the loss of capital, jobs, and turmoil of consolidation.82 Meanwhile, India followed in the footsteps of the U.S. deregulation approach and still has room for further consolidation currently with four carriers with more than 10% domestic market share and a couple in the ditch. Nevertheless, domestic travel is booming in both India and China. For example, China Southern (already the sixth-largest airline globally) plans to grow its fleet by a full one-third in just two years.83

Due to their domestic market scale, Chinese and Indian carriers are bound to make it to the global leaderboards eventually. Even others such as Etihad, Emirates, Qatar, and Turkish airlines can become viable regional players or even global players through investment and alliances. Meanwhile, Covid-19 reshuffled the deck for the industry and propelled Zoom Communications’ market cap to over $48 billion, more than the market value of the top seven airlines combined (just over $46 billion, led by#1 Southwest Airlines [$14.04 billion] and rounded up by #7 Air France [$2.14 billion])! In all, the largest seven carriers lost 62% of their value between January and May of 2020.84

When an industry is dominated by firms from the same country (e.g., the U.S. in aerospace after WWII, soft drinks), then all three players race across continents to form the Global Rule of Three from one geography. Japan experienced this, and at one time, the largest watchmakers as well as TV manufacturers were all Japanese firms. In investment banking, JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley are emerging as global players and even after extending the list to include Bank of America (BofA) Securities and Citi that round up the global top five, all are notably based out of the U.S.85 We will see many more examples of this with China and India dominating entire sectors globally in the future.

In order to survive as a global player, you have to be strong in all three triad markets, or at least in two of them. If a company is strong in only one market, and the industry globalizes, it may only remain a regional player (market specialist ) in the long run, and will ultimately be bought out by one of the global players. The axioms of the Global Rule of Three can be summarized as follows:

Global Rule of Three Generalizations

When the market globalizes, many full-line generalists that were previously viable as such in their secure home markets are unable to repeat that success in a global context. When this happens, we usually find that there are three survivors globally; typically, but not necessarily, one from each of the three major economic zones of the world: North America, Western Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region. To survive as a global full-line generalist , a company has to be strong in at least two of the three legs of this triad.

The path to global dominance relies on aligning procurement/supply chain/finance while staying on top also requires strategic marketing proficiency.

Firms with global aspirations have to conquer their home markets first. A weak domestic base becomes a hindrance during global expansion.

Global consolidation continues until a clear leader emerges and the top three players all command a minimum critical share (i.e., 10%) of the global market each.

Firms with global aspirations need to craft the right attack strategy. A good product at a lower price penetrates the markets faster than a great product at a premium price.

Timing is important. Expansion is easier if an industry is going through (de)regulation or shakeout.

Attack as a pack: Your traditional suppliers, distributors, and even competitors may consider entering at the same time. There are synergies and it may even trigger a paradigm shift in how the new players are perceived. (Koreans did this with LG, Daewoo, Hyundai, and Samsung entering markets within a short period of time.)

Much of the discussion up to this point has focused on generalists. Yet by definition, there can at most be a handful of generalists in each market which eventually consolidate in the convergence to the big three. Meanwhile, there are hundreds of viable specialists globally. Niche companies/specialists in a globalizing market have four options: (a) they can expand internationally and become a global niche player, (b) they can remain domestic as a superniche company, (c) they can launch new specialist businesses, or (d) they can let themselves be acquired at a premium. Many specialists will experience at least two of these options, if not more, in the coming decades.

Online specialists are advised to think locally and act globally—create supply diversity by organizing peer-to-peer networks and connecting them globally. Then take the best of these products and look for ways to scale them and make them global.

One cannot be loyal to a channel as a global generalist, while this may still be possible for a specialist. For example, Pizza Hut refused to engage in delivery for a long time and lost market share to Papa John’s and others in the process. Starbucks, in addition to expanding the number of its locations, also began to sell through supermarkets. This is also consistent with Amazon’s recent foray into brick and mortar, its Whole Foods acquisition, and plans to operate more physical stores soon.86

There is something special about the number three in so many contexts that it is worthwhile reflecting. For example, as a writing principle, Rule of Three implies that a trio of events or characters is more effective for engaging the reader, for example, The Three Musketeers, Three Little Pigs. As a presentation technique, in advertising slogans, and journalism, the Rule of Three also comes up consistently since audiences tend to remember three things: “A Mars a day helps you work, rest and play.” Rule of Three can convert an ordinary speech to a moving one, for example, “Veni, Vidi, Vici” (Julius Caesar), “Friends, Romans, Countrymen” (Shakespeare in Julius Caesar), “Blood, Sweat and Tears” (General Patton), “Government of the people, by the people, for the people” (Gettysburg Address), “the Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” The Rule of Three in Finance refers to trading patterns and expectations of traders regarding three successive trading outcomes. In Statistics, The Rule of Three means that “3/n is an upper 95% confidence bound for binomial probability p when n independent trials no events occur.”87 In other words, let’s say you read the first 200 pages of this book and found no typos. We can all hope that the rest of the book is typo-free but the statistical Rule of Three would imply that the probability of your finding a page with a typo in the rest of the book would be under 1.5% (3/200).88 In history, triumvirate (troika in Russian) refers to three individuals sharing political power for administration (Caesar, Crassus, Pompey; Anthony, Lepidus, Octavian). In perception, a third dimension adds sufficient complexity. In physics, a tripod is more stable than a square-shaped object. In government, the balance of power is maintained through legislative, executive, and judicial bodies. Finally, the trinity principle which contrasts with the duality (either/or thinking) in the Western cultures is commonplace in religion (Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit). Religious affiliations in the world are led by three religions with Christianity 31%, Islam 24%, and Hinduism 15% “market share.”89 In the U.S., Christian denominations are divided into three large groups: Evangelical Protestantism, Mainline Protestantism, and the Catholic Church90 The third dimension is critical and usually strategically different than the first two: for example, body, mind, and soul.91 Hence, three appears to represent a universal structure for balancing the phenomena, whatever it may be.

We observe that three global players have already emerged in several narrowly defined product markets: cellular baseband processor vendors (Qualcomm, MediaTek, Samsung), cigarette vendors (CNTC, PMI, BAT), cloud IT infrastructure vendors (ODM Direct, Dell, HPE/H3C), credit card processing (UnionPay, Visa, Mastercard), CRM vendors (Salesforce.com, SAP, Oracle), DRAM chip vendors (Samsung, SK Hynix, Micron), external enterprise storage systems vendors (Dell, NetApp, HPE/H3C), graphics chip vendors (Intel, Nvidia, AMD), hard copy peripherals vendors (HP, Canon, Epson), mobile internet browsers (Chrome, Safari, UC Browser), LCD TV vendors (Samsung, Sony, LG), security appliance vendors (Cisco, Palo Alto Networks, Fortinet), smart speaker vendors (Amazon, Google, Baidu), server system vendors (HPE, ODM, Dell), storage hardware vendors (EMC, NetApp, IBM), tablet vendors (Apple, Samsung, Huawei), and vaccine companies (GSK, Merck, Pfizer). (Please refer to the Appendix for many more global markets and our projections for 2030.)

Next, we discuss the new triad power and its impact on global markets, resources, geopolitical alignment.

The Rule of Three emerges locally, nationally, regionally, and ultimately globally.

The average life-span of an S&P 500 firm went down from 90 years in 1935 to under 18 years today, and 90% of Fortune 500 firms from 1955 are no longer on the list.

Competitive markets evolve in a predictable fashion across industries and go through similar life cycles. There is a common structure that provides the highest levels of profitability and stakeholder well-being for the entire industry.

The market-driven economy is causing weak companies to exit, get acquired by global competitors, or become specialists, often based on geographic region.

No matter how large the market, the Rule of Three prevails.

Many generalists that are dominant in their countries or regions are unable to have the same success when the market globalizes. When this happens, there is generally one global survivor from each of the three major economic zones.

For a company to survive and succeed as a global, full-line generalist , they must be prominent in at least two of the three legs of the global triad.

If a country has a large stake in an industry, it may be home to two or even all three full-line players.

The path to global dominance relies on aligning procurement, supply chain, finance while staying on top also requires strategic marketing proficiency.

Firms with global aspirations have to conquer their home markets first. A weak domestic base becomes a hindrance during global expansion.

Global consolidation continues until a clear leader emerges and the top three players all command a minimum critical share of the global market each.

Firms with global aspirations need to craft the right attack strategy. A good product at a lower price penetrates the markets faster than a great product at a premium price.

Timing is important. Expansion is easier if an industry is going through (de)regulation or shakeout.

Attack as a Pack: Your traditional suppliers, distributors, and even competitors may consider entering at the same time. There are synergies and it may even trigger a paradigm shift in how the new players are perceived.

One cannot be loyal to a channel as a global generalist, while this may still be possible for a specialist.

Specialists in a globalizing market have four options: (a) they can expand internationally and become a global niche player, (b) they can remain domestic as a superniche company, (c) they can launch new specialist businesses, or (d) they can let themselves be acquired at a premium. Many specialists will experience at least two of these options, if not more, in the coming decades.

Online specialists are advised to think locally and act globally—create supply diversity by organizing peer-to-peer networks and connecting them globally. Then take the best of these products and look for ways to scale them and make them global.