Until early in the 20th century, art in Ecuador was mainly associated with the colonial School of Quito, but the first three decades of the 1900s saw the rise of a school called indígenismo (indigenism).

As Ecuadorian artists have not been isolated from currents in the international art world and many of them have studied or traveled in Europe and North America, the unifying factor of the indigenist school has not been the style of painting, which ranges from Realist to Impressionist, Cubist, and Surrealist, but the subject matter; Ecuador’s exploited indigenous population.

Mural depicting the discovery of the Amazon by Oswaldo Guayasamin, on display in the central staircase of Palacio de Carondelet.

Getty

Inspired by a Sierra life

Eduardo Kingman is perhaps the prototypical indigenist. From the 1930s until his death in 1998 he painted murals and canvases, and illustrated books exploring social themes and the use of color. Juguetería (Toy Store), an oil painted in 1985, shows the back of a barefoot indígena girl peering into the window of a brightly lit toy shop. The toys are rendered in cheerful primary colors, while the girl outside in the shadows, the picture of longing, is painted in somber burgundy, black, and blue.

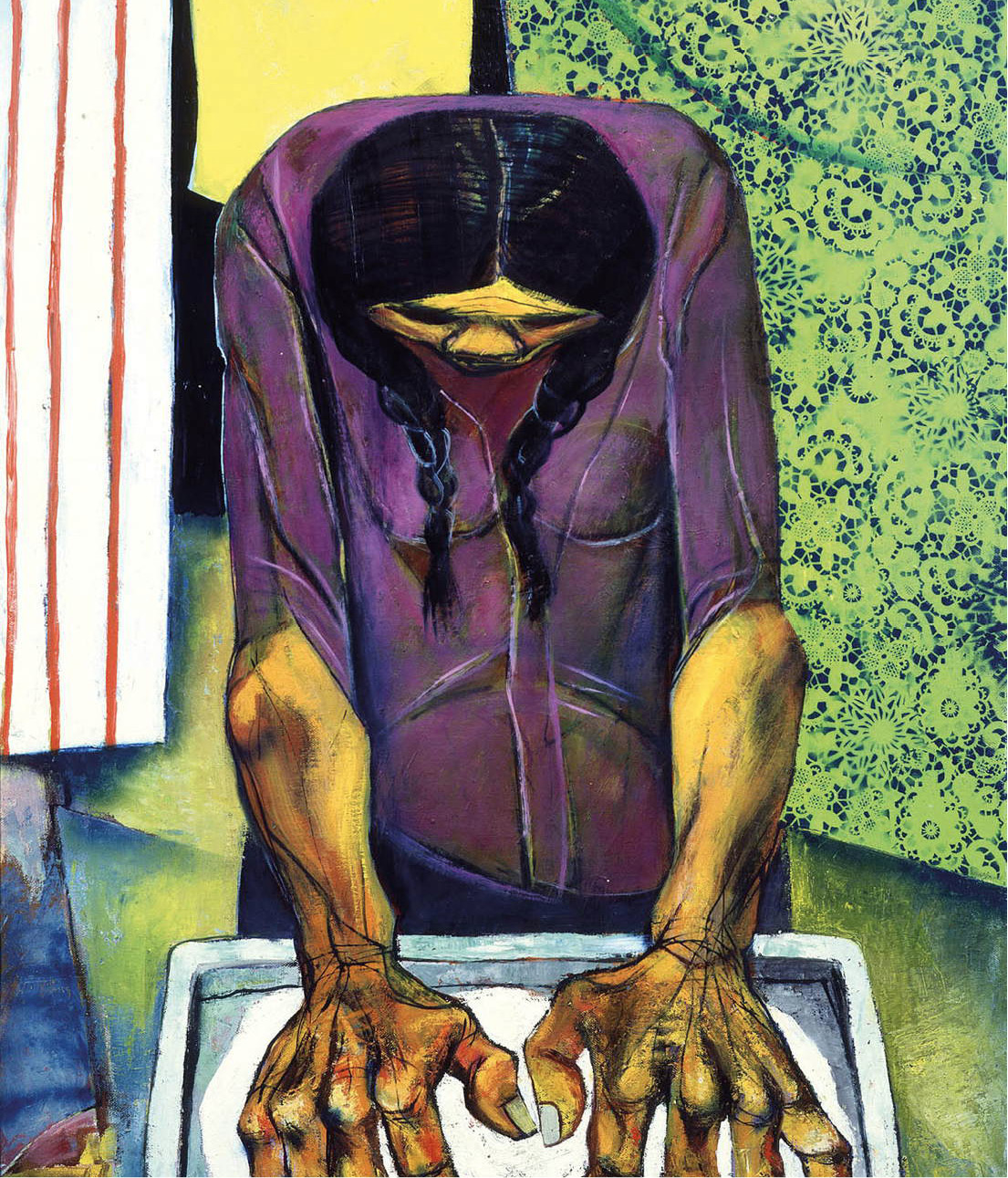

Such paintings as Mujeres con Santo (Women with Saint), El Maizal (The Maize-Grower) and La Sed (Thirst) are characteristic of Kingman’s work: the indigenist subject matter and highly stylized, semi-abstract human figures with heavy facial features and huge, distorted hands. These paintings convey powerful images of oppression, sorrow, and suffering.

Camilo Egas went through a Dalíesque period before he went on to become the most indigenist of the Ecuadorian painters.

Camilo Egas, who died in 1961, lived in France for long periods of time and moved through a range of styles, from Surrealist to Realist, and abstract Expressionist. In Indios (Indians), painted in the 1950s, three longhaired men lean diagonally into the picture, using ropes to haul an unseen burden. The painting is executed in a few bright, clear colors: blue sky, black hair, brown skin, red, white, and yellow clothing. Neither the bodies nor the features of the men are abstract or distorted, and the impression conveyed is one of dignity and strength rather than misery. He also produced El Indio Mariano, a beautiful profile portrait in the same idiom.

Manuel Rendón was a prolific painter who produced a remarkably diverse body of work. Rendón spent his youth in Paris, where his father was the Ecuadorian ambassador, and he was greatly influenced by the modern art movement in France. Rendón is considered an indigenist artist, but he is equally well known for his Cubist-style paintings of men and women in the 1920s and for a series on the Sagrada Familia (Holy Family) in the 1940s. He also painted pointillistic figurative and abstract works, and did many sketches in pencil and pen and ink.

An example of the indigenist painting style, by Eduardo Kingman

The Picture Desk

Ecuadorian maestro

Oswaldo Guayasamín, who died in 1999, is the best known of the generation of artists who came of age in the 1930s and 1940s. His father was an indígena, and Guayasamín consistently and proudly emphasized his indigenous heritage. Few people are neutral about Guayasamín’s work, with its message of social protest. His admirers see him as a gifted artistic visionary and social critic, while his detractors see him as a third-rate Picasso imitator whose innumerable paintings of indígenas with coarse features and gnarled hands have become parodies of the genre. Make up your own mind by visiting the Museo Guayasamín in Quito.

Anyone familiar with the graphic paintings and statues of Christ, agonized and bleeding, in Spanish colonial churches can trace this theme of suffering in Guayasamín’s work, although his figures are secular rather than religious.

One of his early works, the 1942 painting Los Trabajadores (The Workers) is realistic in a manner similar to that of the Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco. The similarity is more than coincidental, as Guayasamín worked with Orozco in Mexico. Guayasamín went on to develop a style influenced by Cubism, with its chopped-up and oddly reassembled images, notably in his series of monumental paintings La Edad de la Ira (The Age of Anger), Los Torturados (The Tortured), and Cabezas (Heads).

Oswaldo Guayasamín, Ecuador’s most famous painter.

Getty

In 1988 Guayasamín continued to make visual political statements with his enormous mural in the meeting hall of the Ecuadorian Congress in Quito, in which 23 panels convey episodes from Ecuador’s history; Guayasamín produced anything but a romanticized picture. Nineteen of the panels are in color, four are in black and white. The latter depict the first Ecuadorian president to enslave the indígenas, Ecuador’s civilian and military dictators, and a skeletal face wearing a Nazi helmet emblazoned with the letters “CIA.”

While Ecuadorians took the mural in their stride, the United States was outraged. The US ambassador called for the letters to be painted out and various US congressmen discussed cutting off economic aid to Ecuador. Guayasamín regarded this as exactly the kind of bullying that he was protesting against, and the panel has remained unchanged.

Perhaps what will become his most famous work was only finished after his death at the insistence of his family. La Capilla del Hombre, in the Bellavista neighborhood of Quito, is rapidly becoming known as his masterpiece. The stone temple resembles an ancient pre-Columbian one on the outside, but inside it is very modern, with fine woodwork and architectural design. A mural depicts the Latin American man from pre-Columbian times to the present. An eternal flame marks the altar on the lower level, which burns for peace and human rights. The minimalist chapel shows the dreams, fears, anguish, inspirations, and love of this great artist.

La Capilla del Hombre in Quito.

Getty

An artistic immigrant

Olga Fisch arrived in the country more than half a century ago as a refugee fleeing from Hitler, bringing with her a background in the visual arts. Fisch was among the first to recognize the value of Ecuadorian artesanías as art, and the design potential of traditional motifs. A talented painter, Fisch is best known for her work in textile design, especially rugs and tapestries, based on her interpretations of pottery, embroidery and weaving motifs. She also designed clothing and jewelry, available at her two stores in Quito.

Where to see Ecuadorian art

The Casa de la Cultura on Avenidas Patria and 12 de Octubre in Quito has a good collection of modern art, with 20th-century sculptures on the lawn outside. The Museo y Taller Guayasamín, at Calle Bosmediano 543, is devoted solely to Guayasamín’s work. La Capilla del Hombre is five blocks up from the Museo Guayasamín at Lorenzo Chávez EA18-143 and Mariano Calvache. The Centro Cultural Metropolitano, at García Moreno and Espejo, and the Museo de Arte Contemporánea, at Luis Dávila y Venezuela in the San Juan neighborhood, have exhibitions. Ecuador’s largest international art exposition is the Cuenca Bienal, held in odd-numbered years.

Modern-day artists

The younger generation of painters has moved away from indigenismo to more personal, idiosyncratic themes and subject matter. In the 1970s Ramiro Jácome was part of the neo-Figurative movement, a return to works with recognizable figures. In the early 1980s he changed his style, painting a series of abstract oils, characterized by deep, rich colors. Later in the 1980s he returned to figurative works. In Barrio (Neighborhood), painted in 1989, three semi-abstract people are delineated by swift, black brushstrokes. They lean against storefronts in what looks like a seedy downtown neighborhood, and the use of yellows and reds contributes to a carnival-like atmosphere. Jácome’s 1990 oil A la Cola (To the End of the Line) depicts a slashing rainstorm in which three bright-yellow taxis outlined in black divide the canvas diagonally. They are balanced by a mass of frantic people in the upper left, rendered in swirling lines of black and white. The painting effectively conveys the feeling of desperation familiar to anyone who has ever tried to catch a taxi in Quito in the rain.