The Andes are often thought of as the spine of Ecuador, but a ladder is a better analogy. Think of the Eastern and Western cordilleras as the sides of the ladder, with the lower east–west connecting mountains (called nudos or knots) as the rungs. Between each rung is an intermontane valley at about 2,300 to 3,000 meters (7,000 to 9,000ft) in elevation, with fertile volcanic soil.

The valleys are heavily settled and farmed today and were the territory of different ethnic groups in pre-Inca times. Both the Pan-American Highway and the railroad run north–south between the cordilleras, bobbing up and down over the nudos past fields, farms, and startled cows beneath a range of dormant and active volcanoes, some of which have snow all year round.

A chiva bus driving through the Avenue of the Volcanoes near Quilotoa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

In 1802 the German explorer Alexander von Humboldt named this route the “Avenue of the Volcanoes.” Ecuador’s position on the equator means that you can travel through the avenue past orchids and palm trees, but with tundra vegetation, glaciers, and snow visible in the mountains above. By leaving the valley and hiking or climbing upward you can pass through all the earth’s ecological zones from subtropical to Alpine.

A splendid way of traveling down the “avenue” is by rail, but you will need to check which lines are running on the Tren Ecuador website (www.trenecuador.com). If open, the railroad does allow you to get an intimate look at life along the tracks, traveling through people’s back yards, so to speak, rather than down the main road. The route suggested in this chapter, however, takes the Pan-American Highway, with detours and side roads to places of interest on the way.

The road south

Leaving Quito 1 [map] by car or bus for the south can seem to take for ever, as the streets leading to the Pan-American Highway are usually jammed. However, there is a bypass, the Nuevo Oriental, which connects with the Pan-American Highway on the outskirts of south Quito, and makes driving much less stressful. The road goes through the Valle de los Chillos and connects with the main highway about 8km (5 miles) farther south. The traffic eases a bit as you wind down off the Quito Plateau and into the first intermontane valley. Way off to the east the snowy peak of Volcán Antisana (5,750 meters/18,860ft) can be seen.

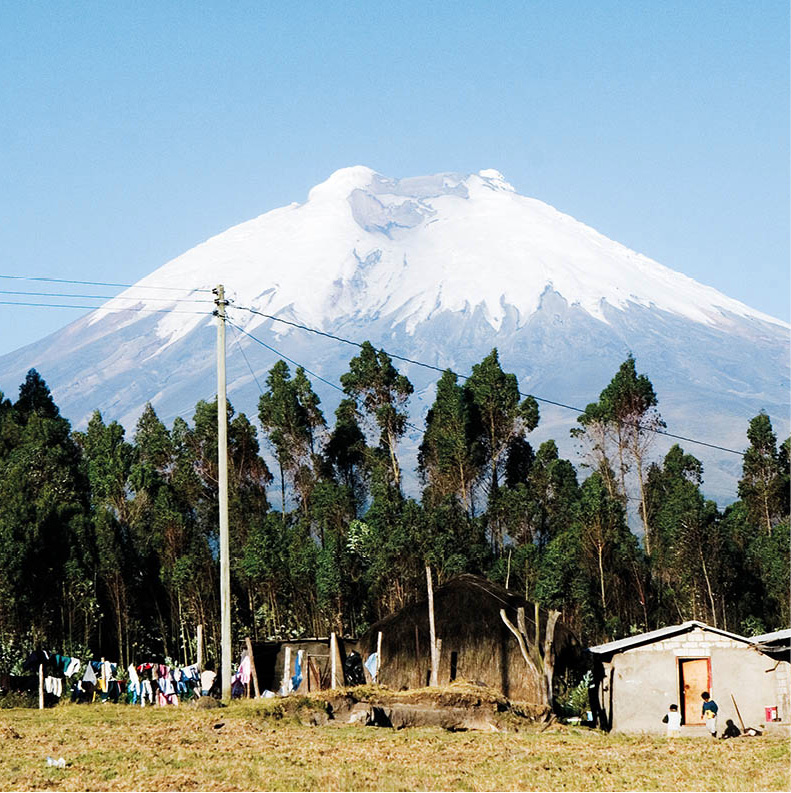

Mount Cotopaxi is Ecuador’s highest active volcano.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Looming over the region is Volcán Cotopaxi (5,897 meters/19,350ft), Ecuador’s second-highest peak and one of the world’s highest active volcanoes. On a clear day you can see its symmetrical, snow-capped cone from Quito. In the Western Cordillera, almost directly across from Cotopaxi, is Volcán Illiniza (5,248 meters/17,218ft), or the Illinizas as they are called, for there are actually two peaks. The lower, northern peak is a satisfying climb for non-technical climbers and hikers, while the southern one, Illiniza Sur, is only for those with experience.

Some 32km (20 miles) beyond Machachi, just over the first pass, is the entrance to the magnificent Parque Nacional Cotopaxi 2 [map].

Both sides of the highway are covered by a forest of Monterrey pines, many of them unfortunately dying from a fungal disease. The pines are not native; they were introduced from California for a forestry project and are a textbook example of the dangers of monoculture: the pines have crowded out the indigenous vegetation and the fungus has spread rapidly from tree to tree.

The national park centers on Cotopaxi, of course, but there are several other peaks that attract rock climbers, including Rumiñahui (4,712 meters/15,460ft), and there is also a great variety of wildlife, ranging from falcons and highland hummingbirds to tiny deer and the endangered, and rarely seen, Andean puma.

Fact

The origin of the Quichua name Cotopaxi is not clear, and has had several different interpretations. Some translate it as the combination of two Quichua words: kotto, meaning peak or mountain, and paksi, denoting shining. Another interpretation comes from the words cutu, meaning neck, and pachi, broken – which sees Cotopaxi as a headless neck with a white poncho of snow. Yet another translation denotes it, rather evocatively, as the “neck of the moon.”

Haciendas and markets

As elsewhere in Latin America, the prime agricultural land in the valley was taken from the indigenous population soon after the Spanish conquest and turned into large Spanish-owned haciendas (estates), many of which still exist and include vast landholdings, despite the Agrarian Reform of 1964.

Several haciendas are also found in the less productive, windswept high páramo. Of these, the closest to Cotopaxi is Hacienda el Porvenir (tel: 02-2041520; www.tierradelvolcan.com). This is the perfect base for some high-altitude acclimatization: there are wonderful walks and bike rides on the property, as well as adventurous horseback riding into the national park. Guided ascents of the volcano can also be arranged. The same company also owns remote, rustic Hacienda El Tambo, on the far side of Cotopaxi, and Hacienda Santa Maria, where there is a complex of aerial zip lines to take you flying over forest and river.

Parading through the streets of Latacunga during the Mamá Negra festival.

Quito Visitors Bureau

Very close by, just south of Machachi, is possibly one of Ecuador’s most distinctive haciendas, San Agustín de Callao (tel: 03-271 9160; www.incahacienda.com). San Agustín is built on the site of an Inca palace, one of the two most important Inca constructions in Ecuador, and its dining room and chapel are built entirely within the original Inca stonework. Stay here amongst the antiques, murals and whispering masonry walls, and you will feel deeply immersed in history. There’s also a whole program of activities, including hikes to the top of Cotopaxi, visits to some secret angling spots, or horseback rides across the páramo on one of the hacienda’s beautiful steeds.

Farther south, towards Latacunga is the small town of Lasso. Turn off west here for Hostería La Ciénega (tel: 03-271 9052; www.hosterialacienega.com). Now a hotel and restaurant, its main house – a stone mansion with huge windows, stone-cobbled patios and Moorish-style fountains – was built in the mid-1600s for the Marquis de Maenza and was occupied by his family for more than 300 years. The stone chapel has a bell, still rung on Sunday mornings, which was installed in 1768 in thanksgiving when Cotopaxi ended 20 years of devastating eruptions. Von Humboldt stayed here in 1802 when he surveyed Cotopaxi, and the de Maenza-Lasso family plotted Ecuador’s independence from Spain on this site in the 1800s. The comfortable rooms are beautifully furnished with antiques and chandeliers. Besides opportunities for excellent bird-watching in the gardens, you can ride horseback from here and make day trips to Cotopaxi National Park.

Colorful woven bags in Guamote’s Thursday market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The little towns in the valley, and the larger city of Latacunga 3 [map] (pop. 50,000), are interesting primarily for their fiestas and market days. Some 90km (56 miles) from Quito, Latacunga is somnolent and pleasant, with a number of buildings constructed from local gray volcanic rock. It was founded in 1534 on the site of an Inca urban center and fortress. There are busy Saturday and Tuesday markets, where crafts are sold, especially shigras (bags), baskets, and ponchos.

Shepherd tending his flock near Quilotoa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Fiesta de la Mamá Negra

Latacunga’s festival of the Virgin of the Mercedes, commonly known as the Fiesta de la Mamá Negra (the Festival of the Black Mother) takes place twice a year: on September 23 and 24 and again in November to coincide with the anniversary of the city’s founding. It’s a lively event with obvious indigenous influences, despite its Christian name and outward trappings, which of course include paying homage to the figure of the black-faced Virgin Mary.

There are huge street parades with allegorical figures, often making satirical, social, or political points; masquerades; local bands; noisy firework displays; and dancing in the streets late into the night. There is also a solemn Midnight Mass (misa del gallo) although some of the celebrants are a little less than solemn.

Latacunga’s municipio (town hall) and cathedral are on the main plaza, the Parque Vicente León, which has topiary and a well-maintained garden. Behind the cathedral is a colonial building housing an arcade with shops, offices, and an art gallery. Five blocks west down Calle Maldonado at Calle Vela is the Casa de la Cultura (Tue–Fri 8am–noon and 2–6pm, Sat 8am–3pm), built on the remains of a Jesuit monastery and the old Montserrat watermill. The museum houses pre-Columbian ceramics and weavings, and a library, theater, and gallery. Some 10km (6 miles) west of Latacunga is Pujilí, which has a lively market on Sunday, and colorful Corpus Christi festivities in June.

Quilotoa crater lake.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

A wild and scenic loop west of Latacunga takes you through the market towns of Zumbagua, Chugchilan, Sigchos, and Saquisilí, then back to Latacunga. Zumbagua’s market on Saturday is stocked with a kaleidoscopic array of fresh produce. Half an hour’s drive farther on is Lake Quilotoa, an azure, water-filled volcanic crater, still considered active. Indigenous people from the Tigua Valley nearby sell naïve, brightly colored enamel paintings on sheepskin at the crater rim. On the way north from here to the village of Chugchilan is the Black Sheep Inn (tel: 03-281 4587; www.blacksheepinn.com), an ecological farm with delicious home cooking and great views over the sierra. The whole loop back takes several hours along mainly dirt roads, so a stop here is a welcome break. Saquisilí only comes out of its torpor on Thursday market day. The market is an economic hub for the surrounding region, with indígenas buying and selling everything from cattle to cotton. The market is decidedly a local, rather than tourist, affair and a favorite with many travelers for that reason.

Another 10km (6 miles) farther south you cross the provincial boundary and enter Tungurahua province, named after the area’s dominant volcano. The region is known for its relatively mild climate and production of vegetables, grain, and fruit, including peaches, apricots, apples, pears, and strawberries, and you will encounter roadside vendors along the highway on both sides of the city of Ambato.

Ambato

Some 128km (80 miles) from Quito, Ambato 4 [map] is the capital of Tungurahua province. Arriving in the city brings you abruptly face to face with the 21st century. Ambato was almost totally destroyed by an earthquake in 1949 and then rebuilt, so virtually nothing of the colonial town remains. With a population of about 150,000, the city is the sixth-largest in Ecuador. Industries include some textiles (especially rug-weaving), leather goods, food-processing, and distilling, but the most interesting aspect of Ambato is its enormous Monday market, the largest in Ecuador. Thousands of indígenas and country people come into town for the different activities, which take place in various parts of the city. Several plazas contain nothing but produce vendors, while the streets are lined with kiosks selling goods of all kinds. To reach the textiles, dyes, and crafts (ponchos, ikat blankets and shawls, shigras bags, belts, beads, hats, and embroidered blouses), follow Calle Bolívar or Cevallos about 10 blocks north from the center of town to the area around Calle Abdón Calderón.

Indígena in Salasca market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Ambato’s attractive central plaza is Parque Montalvo, named for the writer Juan Montalvo (1833–99) and bearing a statue to the same. Montalvo’s house, at calles Bolívar and Montalvo nearby, is open to the public. Ambato, in fact, is often known as “La Tierra de los Tres Juanes” (Land of the Three Juans) because Juan Leon Mera (who wrote Ecuador’s national anthem) and the renowned teacher Juan Benigno also heralded from here. On the north side of the plaza is Ambato’s modern cathedral, and opposite is the post office. The Parque Cevallos, a few blocks to the northwest, is green and tree-lined, and is the site of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales (Natural Science Museum; Mon–Fri 8am–noon and 2–5.30pm), packed with stuffed animals and birds of the region. The Río Ambato flows through a gorge to the west of the town center. A paved road leads out of Ambato to the east, past Volcán Tungurahua and down into the Oriente, forming one of the main east–west links between the jungle and Sierra.

Traditional woven rugs for sale in Salasca.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

From Ambato, catch a bus or truck 20km (12 miles) northeast to the small town of Píllaro. This is the way to get to the Parque Nacional Llanganates, which is perpetually wrapped in fog and covered with virtually impenetrable cloud-forest vegetation. These remote mountains appeal to the Indiana Jones in all of us because of various accounts of General Rumiñahui hiding Quito’s gold here, before Benalcázar and the conquistadores could get to it.

The people of Salasaca

About 14km (9 miles) east of Ambato on the road to Baños is Salasaca, the home of a small, beleaguered indigenous group, thought to be of Bolivian origin, which is struggling to hold on to its land and maintain its customs in the face of enormous pressure from criollos in the surrounding communities. This group is thought to be mitmakuna, living here as a result of the Incas’ policy of forcibly moving whole tribes from their homelands to distant foreign territories as punishment for uprising or the threat of it.

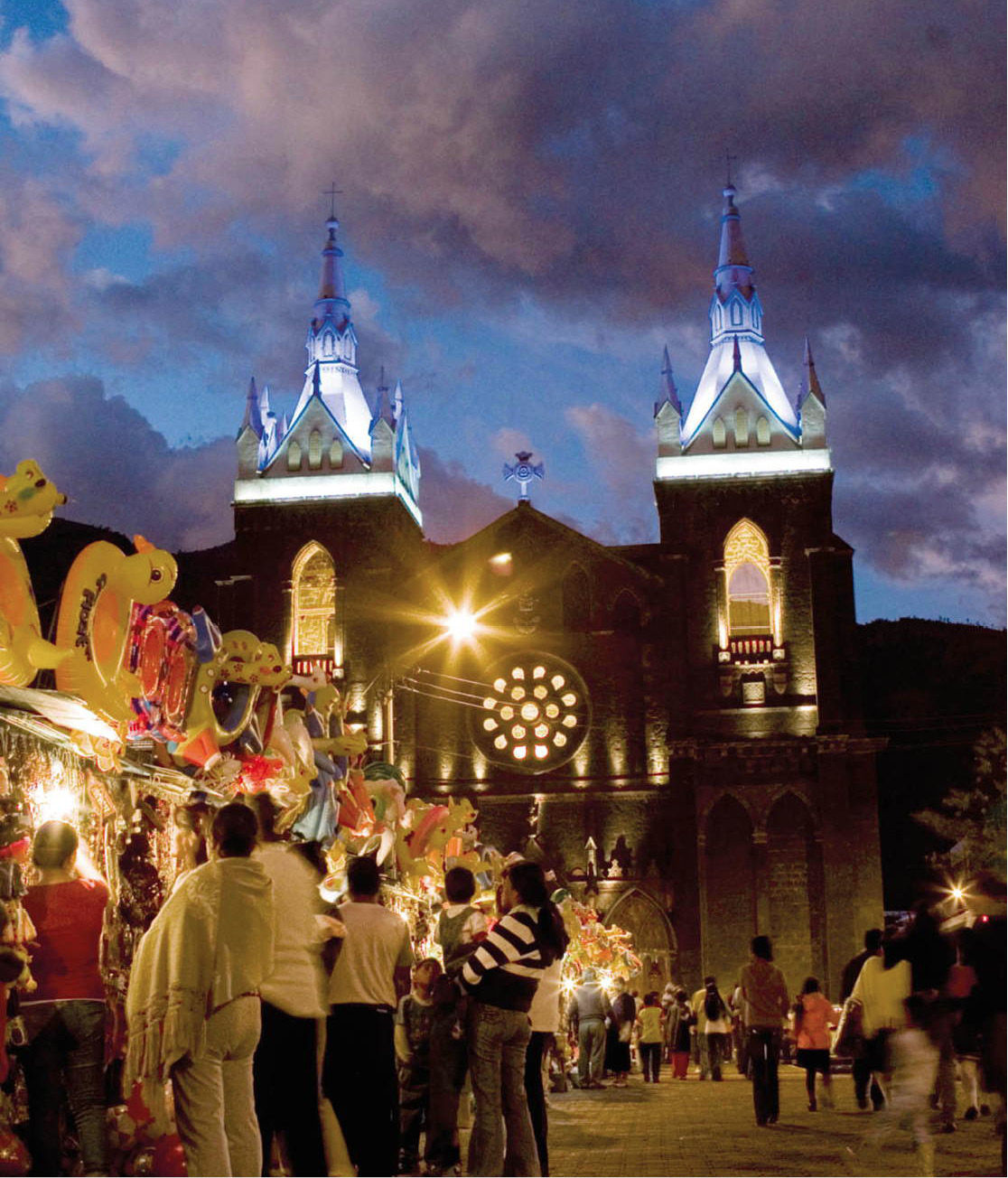

Street stalls in front of the basilica of Nuestra Señora del Agua Santa, Baños.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Salasaca men wear black and white ponchos and handmade white felt hats with broad, upturned brims at the front and back. Unique to Salasaca are the men’s purple or deep-red scarves dyed with cochineal, a natural dye that comes from the female insects that live on the Opuntia (prickly pear) cactus. Salasaca women wear the same hats as the men, brown or black anakus, cochineal-dyed shoulder wraps, hand-woven belts with motifs, and necklaces of red, Venetian glass beads.

Salasaca market traders.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

A few kilometers past Salasaca is Pelileo, a little town where you would not want to invest in property: it has been leveled by earthquakes four times in the past 300 years. As the last quake was in 1949; the present Pelileo is an entirely modern town. There is a small Saturday market, which is attended by many indígenas from Salasaca. It is also Ecuador’s major production center for blue jeans.

Tip

The Manto de la Novia, San Miguel, San Pedro, and Inés María waterfalls near Baños can all be reached by chiva bus tours.

Baños

Beyond Pelileo the highway drops 850 meters (2,790ft) to Baños in only 24km (15 miles), following various tributaries and then the Río Pastaza itself in its headlong rush to the Amazon basin. The region produces sugarcane for distilled alcohol, and many kinds of fruits and vegetables.

The town of Baños attracts both visitors from Ecuador and foreign travelers.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Baños 5 [map]has always been famous for its thermal hot springs bubbling out of the side of the wild and unruly Volcán Tungurahua (5,023 meters/16,480ft). In 1999 the volcano started erupting again, and the 25,000 townsfolk were evacuated. Residents fought their way back in at the beginning of 2000 at their own risk, even with the volcano spewing hot rocks and ash only 7km (4 miles) away. Another major eruption took place in 2006 accompanied by a 10km (6-mile) -high ash cloud and pyroclastic flows resulting in seven deaths and destroying hamlets and roads on the western and northwestern slopes of Tungurahua. The volcano continued its activity through 2010 and 2011; geologists are still keeping a close watch on the peak and will evacuate the town again if activity increases. Tourist operators in town offer night-time volcano-viewing tours: but check if there are actually any pyrotechnics going on at the time you visit, before signing up.

Eat

In typical holiday town style, Baños does a roaring trade in sweet treats. Most visible is the manufacture of melcocha, a hard toffee made from cane sugar that has to be pulled and shaped in long straps while warm. Melcocheros work the malleable sugar with a deft twisting and throwing action. If you stand and watch long enough, you might be given a bit to try.

Baños is something of an adventure hub for backpackers. Streets full of tour operators tout four-wheel drive buggy tours, mountain biking, bungee-jumping, rafting, canyoning, and discount jungle visits. One of the classic routes in this area (for bicycle, scooter, or by 4WD bike) is to head along the road between Baños and Puyo skirting the deep canyon of the Río Pastaza, surrounded on all sides by cloud-forest-cloaked mountains, and waterfalls. Take care not to enter the many unlit road tunnels, though: there is an unpaved detour round each of them which is safer for pedestrians and cyclists. Some of the waterfalls along this route are spectacular, especially the plume-like Pailón del Diablo and Manto de la Novia, about 20km (12 miles) from Baños, which should not be missed.

The gentle, subtropical climate of Baños (altitude 1,800 meters/5,910ft) is another draw, and it makes the region a hiker’s paradise. There are short trails in the hills directly above the town, and nearby, there are the little-explored national parks of Los Llanganates and Sangay, two of the most biologically diverse areas in the world. With luck and patience, four kinds of monkey, spectacled bears, mountain tapirs, and birds such as the cock-of-the-rock and black and chestnut eagle can be seen in the forests here. The area is also home to an exceptionally high diversity of plants, many still unknown to science. A recent study of just one genus of orchid has turned up 14 new species.

Eat

Baños has its own version of the Hard Rock Café, called the Jack Rock Café. It’s a quaint little place in the middle of a strip of bars.

While foreign travelers come to Baños for the hot springs, hiking, and adventure activities, many Ecuadorians come here to pay homage to the Virgin of Baños, known as Nuestra Señora del Agua Santa (Our Lady of the Holy Water), whose statue is housed in the basilica in the center of town. The Virgin is credited with many miracles, including delivering people from certain death in a fire in Guayaquil, and saving the lives of travelers when a bridge over the Pastaza River collapsed. The walls of the basilica are hung with paintings depicting these events. The basilica grounds have a small museum with moldering stuffed tropical birds and the Virgin’s changes of clothing.

From Baños, return to Ambato (buses are frequent and the journey takes about an hour) and make a trip to the west. A paved road circles around Volcán Carihuairazo (5,020 meters/16,470ft) and Volcán Chimborazo (6,310 meters/20,700ft) and heads for Guaranda and the coast. Chimborazo is the highest peak in Ecuador, and it looms over the provinces of Chimborazo, Bolívar, and southern Tungurahua like a giant ice cream, dominating the landscape. The Reserva Producción Faunística Chimborazo (Chimborazo Fauna Reserve), which surrounds the mountain, is the place to visit for views, high-altitude hiking, and to see some of the way of life of the remote, chilly indigenous villages in the area. The reserve covers a vast 56,560 hectares (139,800 acres) between 3,800 meters (12,470ft) above sea level to the summit of Chimborazo, and is home to vicuña, llama, and alpaca; the last are also prized livestock for local people. Foxes and deer are also seen here, condors often soar overhead, and this is one of the few places to see the giant hummingbird (Patagonia gigas), which due to its cold-temperature habitat, hibernates at night and wakes up with the sun. High-altitude polylepis forests are also a fascinating feature of the park, as are the pre-Inca sites of worship on the mountain’s flanks, where local villagers still make ritual offerings.

The trees at the top of the world

The amazing polylepis tree is found growing in sparse patches in the high Andes; indeed, it has the unique distinction of being the tree that grows at the highest elevations in the world. Stands of this ancient, gnarled, slow-growing tree with its bark as flaky as paper (hence the Greek name, meaning “many scales”) are found between 3,800 and 4,600 meters (12,000–15,000ft) above sea level. This is remarkable because the natural treeline of the Andes (above which other trees cannot grow) is much lower: 3,200–3,500 meters (10,000–11,000ft) above sea level.

Polylepis trees usually grow in sheltered, inaccessible gulleys in high-altitude grasslands such as the Ecuadorian páramo, but researchers believe they may once have covered much more extensive swathes of the Andean range, and that existing forests are just the remnants that remain after millennia of being used for fuel and construction material. Many polylepis species (there are thought to be 28) are now protected.

Ecuador’s ancient forests are also an important habitat for other endangered plant, bird, and animal species, Furthermore, they help to prevent erosion on steep mountainsides and are the source of many medicinal plants.

The Western Cordillera outside Ambato is the land of emerald mountains. Every inch of the hillsides is farmed by the Chibuleo indígenas, turning the land into a patchwork quilt of every shade of green. Every so often, either Carihairazo or Chimborazo pokes its snowy head out above the clouds. The road climbs to the páramo above 4,000 meters (13,000ft), with some superb views of Chimborazo, then drops again to Guaranda, which is 85km (53 miles) from Ambato. Midway through the journey you enter Bolívar province.

Guaranda and the Chimbo Valley

About 90km (56 miles) from Ambato, the capital of Bolívar province, Guaranda 6 [map](2,670 meters/8,760ft) is a small, sleepy town of 21,000 people that comes alive on Saturday with the weekly market. The town is set among seven hills, one of which, Cruz Loma (Cross Ridge), has a giant statue of an indigenous chief, El Indio de Guarango, a mirador (lookout), and a small, circular museum with pre-Hispanic and colonial artifacts. There are three other small museums in the town with mixed collections, including colonial art and ethnographic material: the Museo Municipal, the Museo de la Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, and the Museo del Colegio Pedro Carbo. Opening hours are variable: check on arrival at the tourist information office located on García Moreno (Mon–Fri 8am–noon and 2–6pm). The Parque Central has a monument to Simón Bolívar, which was a gift from the government of Venezuela. Guaranda is the market center for the Chimbo Valley, a rich agricultural region that produces wheat (trigo) and corn (maíz). A 16km (10-mile) ride through the valley south from Guaranda takes you to San José de Chimbo, an ancient town with colonial architecture and two thriving craft centers. The barrio (neighborhood) of Ayurco specializes in fine guitars, handmade from high-quality wood grown in the province. Tambán barrio produces hunting guns and fireworks, but these are not just any old fireworks. Bamboo frames (castillos, or castles) are fabricated in the shape of giant birds, huge towers, or enormous animals, with fireworks attached. They are set off to striking effect at fiestas throughout the country. It is not uncommon for the castillo to fall over, shooting sky rockets directly into the crowd. Gringos generally jump for cover behind the plaza fountain, but the Ecuadorians love it.

Chimborazo province

Chimborazo province was the pre-Inca territory of the Puruhá tribe. Modern towns such as Guano, Chambo, Pungalá, Licto, Punin, Yaruquíes, Alausí, Chunchi, and Chimbo were all originally Puruhá settlements. But, as elsewhere, the Incas moved people around: they settled indígenas from Cajamarca and Huamachuco, Peru, in the Chimbo region and moved many Puruhá people to the south.

Today, Chimborazo has an amazing mixture of people who wear different kinds of traditional dress, although there aren’t necessarily special names for all these groups. Chimborazo was the site of many obrajes (textile sweatshops) in colonial times and after independence. The indigenous population became increasingly impoverished and marginalized through succeeding centuries as they were pushed by new settlers into the mountains or became attached to the country haciendas as wasipungeros (serfs).

The Chimborazo indígenas did not take mistreatment and injustice lying down. There have been many revolts over the centuries, including an uprising of 8,000 indígenas around Riobamba in 1764, a revolt in Guano in 1778, and a rebellion in Columbe and Guamote in 1803. Land shortages are still a problem, and men from many communities frequently migrate temporarily to the larger cities in search of work. Chimborazo has also seen intensive Protestant evangelical activity, which has often exacerbated tensions.

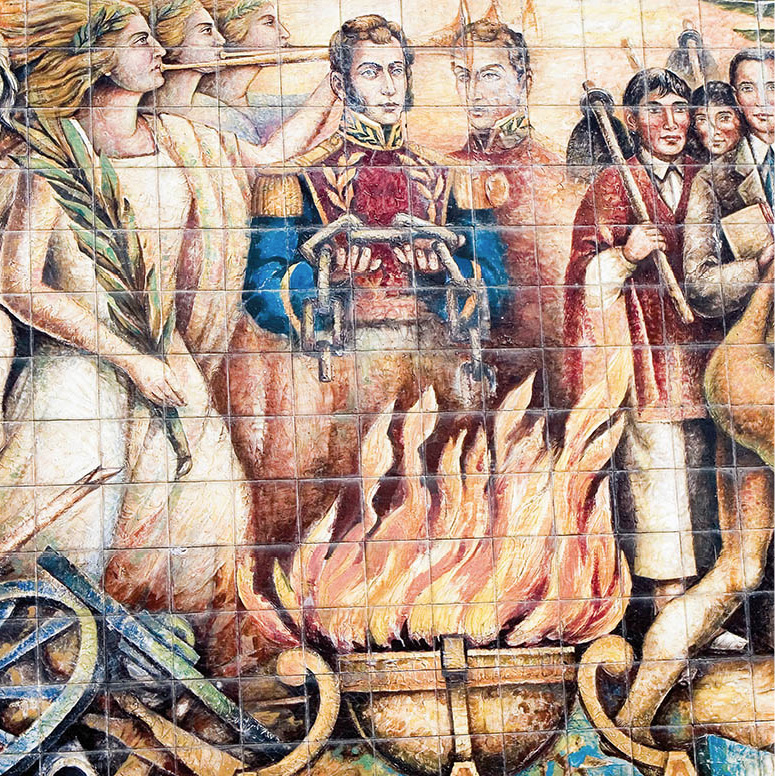

Mural depicting the history of Riobamba in the Parque 21 de Abril.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The most obvious ethnic marker in Chimborazo is hats. While indígenas are increasingly using dark, commercially made fedoras, a large number still wear the handmade white felt hats, especially for fiestas and other special occasions. In the Guamote market you can spot as many as 15 different kinds of white, handmade hat being worn. Such variations as the size and shape of the brim and crown and the color and length of the streamers, tassels, or other decorations all indicate the wearer’s community or ethnic group.

Tip

One of the great experiences in this region is to soar down the side of Chimborazo from its Carrel Refuge (4,800 meters/15,744ft) on a bike. Several companies offer this thrilling 55km (33-mile) descent, but the best is Riobamba bike tour operator ProBici (tel: 03-295 1760; see page “ProBici”).

Riobamba

Riobamba 7 [map]is the capital of Chimborazo province. In 1541 the Spanish chronicler Pedro de Cieza de León began an epic 17-year horseback journey in Pasto, Colombia, riding south along the Royal Inca Highway through Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. By 1545 Cieza de León was in central Ecuador heading for Riobamba. “Leaving Mocha,” he wrote, “one comes to the lodgings of Riobamba, which are no less impressive than those of Mocha. They are situated in the province of the Puruhás in beautiful fair fields, whose climate, vegetation, flowers, and other features resemble those of Spain.” Chimborazo is still primarily an agricultural province, growing crops such as wheat, barley, potatoes, and carrots, with some grazing land for small herds of sheep, llama, and cattle.

Riobamba’s cathedral.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Although at 2,750 meters (9,022ft) Riobamba is only 180 meters (590ft) higher than Ambato, it feels much colder, perhaps because of the wind sweeping down off the glaciers of Chimborazo. The original Riobamba was founded by the Spanish on the site of a major Inca settlement 21km (13 miles) away, where the modern town of Cajabamba stands, but the old town was flattened by an earthquake in 1797 and a new location was chosen. The new Riobamba (pop. 150,000) retains much of its 18th-century architecture and is a relatively sleepy town, except on Saturday, which is market day

Ornate ironwork, Riobamba.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Two areas of the Riobamba market are of particular interest to visitors. Traditional indigenous garments, including such items as hats, belts, ponchos, ikat shawls, fabric, shigras, hats, and old jewelry (beautiful beads, earrings, and shawl pins) are sold in the Plaza de la Concepción on Orozco and 5 de Junio, along with baskets and ikat blankets. In one corner of this plaza people set up their treadle sewing machines and mend clothes or sew the collars on ponchos, while other vendors sell aniline (synthetic) dyes. Just south of this plaza on Calle Orozco is a small cooperative store selling crafts made by the indígenas of Cacha.

Sewing the collar on a poncho in the Plaza de la Concepción, Riobamba.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Another important craft of the Riobamba region is tagua nut carving. The egg-sized seeds of the lowland tagua palm are soft when first exposed to air but then harden to an ivory-like consistency. Tagua is carved into jewelry, chess sets, buttons, rings, busts, and tiny kitchen utensils. Stores selling tagua crafts are found opposite the train station on Avenida Primera Constituyente (Avenue of the First Constitution). The street acquired its name because, after winning independence from Spain, Ecuador’s first constitution was written and signed in Riobamba on August 14, 1830.

About eight blocks northeast of the artesanías plaza is the Plaza Dávalos, where cabuya fiber (made from the Agave americana cactus, the century plant) and products are sold. Cabuya crafts have been an important local industry in the region since colonial times. Indígena women spin the fiber into cordage, used for the soles of espadrilles, rope, sacks, and saddlebags.

After the market has finished, the town empties rapidly and lapses into somnolence for another week. This is your opportunity to visit the Museo de Arte Religioso (tel: 03-296 5212; Tue–Sat 9am–noon and 3–6pm), housed in the Convento de la Concepción on Calle Argentinos. Among the items on display are statues, vestments, and a fabulous gold monstrance encrusted with diamonds and pearls.

Different colored dyes for sale in Riobamba market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

There is also the museum in the Colegio Nacional Pedro Vicente Maldonado (Tue–Sat 9am–noon, 3–6pm) at Avenida Primera Constituyente 2412, with natural history exhibits; the Museo de la Casa de la Cultura (Tue–Sat 9am–noon and 3–6pm) focuses on archeology; and the Museo del Banco Central (tel: 03-296 5501; Mon–Fri 8.30am–5pm, Sat 10am–4pm) located in the bank building downtown, has ethnographic and modern art exhibitions. The Museo de la Ciudad (tel: 03-295 1906; Mon–Fri 8.30am–5pm, Sat 9am–4pm) has temporary and permanent exhibits. Opening times for all these museums can be erratic, so it is worth checking at the tourist information office on Avenida Daniel León Borja, which is not far from the train station. Riobamba also has some majestic old churches, including the cathedral on 5 de Junio and Veloz and the circular basilica (the only one in Ecuador) on Veloz and Alvarado in the Parque La Libertad.

Riobambo lies in the shadow of Volcán Chimborazo.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Climb to the top of the Parque 21 de Abril (located on Calle Argentinos north of the center of town) for views of Chimborazo, Carihuairaso, Tungurahua, and Altar (5,319 meters/17,450ft). This brooding hulk to the south of the city in the Eastern Cordillera is known in Quichua as Capac Urcu (Great or Powerful Mountain). It is better not to visit at sunset, however, as there have been muggings in the vicinity at that time.

Fact

Also known as ivory or ivory-nut palms, tagua palms are an important source of income for indigenous communities, who carve its seeds into craft and commercial items. Their need for the tagua means that it also helps to prevent the destruction of the rainforest.

Exploring the region

Riobamba is a good base for excursions to the rest of Chimborazo province. For a day trip to buy rugs and visit the artisans at work, catch a bus or cab 12km (7 miles) north on a subsidiary road, not the Pan-American Highway, to Guano. The town is known for its cottage-industry production of fine rugs, hand-knotted on huge vertical-frame looms. Most shops have a workshop attached where you can watch the weavers at work. Just a kilometer or two beyond Guano (there is a bus service) is the small town of Santa Teresita, which specializes in the production of carrot or potato sacks woven from cabuya fiber. Many of the weavers have enormous warping frames in their yards, with hundreds of meters of cabuya on them, and you may also see the woven yardage stretched out along the road. At the edge of town is the Balneario Las Elenas, with two cold-water swimming pools and one warmer pool – all fed by natural springs – and a cafeteria.

Most of Chimborazo province lies south of Riobamba, and it’s a part of Ecuador worth exploring. The road to Licto climbs above Riobamba and offers views of the city and the volcanoes.

Guamote’s Thursday market draws indígenas from all over the region.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

A quiet but extremely traditional Sunday market, drawing indígenas from the Laguna Colta area and the usual assortment of vendors, is held in Cajabamba, 13km (8 miles) south of Riobamba on the Pan-American Highway. This was the site of the old Riobamba, which was originally a Puruhá community, and then the Inca settlement of Liripamba when it had fine, mortarless stonework, including a temple of the sun, a house of the chosen women, and a royal tambo (lodge).

Guinea pigs for sale.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The stones from the Inca buildings were then incorporated into the Spanish town, which in turn was destroyed in the 1797 earthquake and subsequent landslide. The only building surviving from the 18th century is the chapel.

About 2km (1 mile) beyond Cajabamba is the tiny town of Balvanera (also spelled Balbanera), on the shores of Laguna Colta. Colta indígenas graze their cattle and sheep along the marshy shores of the lake, and use the totora reeds in the lake to make esteras (mats) and canastas (baskets). Locals claim that the town’s little church, with its image of the Virgin of Balvanera, is the oldest in Ecuador, constructed by the conquistador Sebastián de Benalcázar and his troops after a victory over the Inca forces, but there is no documentary evidence to support this.

Guamote’s Thursday market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

In Guamote (51km/32 miles south of Riobamba), the Thursday market is the major weekly fair for the southern part of the province. Indígenas on horseback or leading llamas laden with produce arrive from communities where no road reaches. At the animal market much of the bargaining takes place in Quichua, but at the food and clothing markets more vendors speak Spanish. You will see more indígenas in different kinds of traditional dress here than at any other market in Ecuador.

Switchback railroad

From here, the highway drops down past Tixan and into Alausí 8 [map] (2,356 meters/7,730ft). Alausí was once used as a resort to escape from the heat of Guayaquil, and has a charming feel, with impressive mountain views, and a quiet way of life except for market day on Sunday. Alausí is most famous for the legendary Nariz del Diablo (Devil’s Nose) railroad that switchbacks between here and Sibambe, dropping precipitously. The railroad used to run all the way to Guayaquil, but many switchbacks were washed away in the El Niño storms of 1982–3. Only the part between Riobamba and Sibambe has been repaired.