The north Pacific coast of Ecuador is one of the best places on the continent to take a break from the sometimes demanding rigors of travel. Much of this varied coastline consists of largely empty, palm-fringed beaches, which present the ideal opportunity to practice one of the foremost customs of ancient Ecuador: sun worship.

This area bore the brunt of the devastating floods of 1982–3 and 1998–9, brought about by the El Niño current, when roads, beaches, trees, crops, and a significant number of dwellings were washed away, although things have now largely recovered.

Juice stall.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

As a string of holiday resorts springs up along the coast, however, the last signs of destruction fade. This development testifies to Ecuador’s growing stature as a tourist destination, due partly to its own charms, and partly to its neighbors’ ill fortunes. A holiday in parts of Colombia, with its cocaine-related civil disturbances, is not for the faint-hearted, while large sections of the Peruvian coastline are washed by the Humboldt Current that brings damp, misty weather and ice-cold waters. Because of this, Ecuador has cornered the market in tropical beaches along South America’s west coast. However, the prevailing security situation should be checked before visiting. Ecuador’s northern Pacific coast has been known to see some of the armed violence that is more prevalent across the Colombian border. Wherever you go on Ecuador’s coast, it is still not a good idea to walk along the beaches alone at night.

Sunset, Puerto López.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Land of two seasons

The wet season on the Ecuadorian coast runs from December to June, the remainder of the year being dry – or perhaps, more accurately, not so wet. During the wet season, when flooding is commonplace and high levels of humidity make life uncomfortably sticky, the beaches – despite being below par – are well patronized. All things considered, August to October is the best time to visit this relaxed region.

The coastal topography consists of a thin lowland strip, which turns from forbidding mangroves in the north to dry scrubland on the Santa Elena Peninsula, west of Guayaquil. A short distance inland runs a range of low, rounded, crystalline hills. The region is cut by numerous rivers meandering down from the Andes, which regularly flood the alluvial plain that lies to the east of the hills. Huge alluvial fans, often consisting of porous volcanic ash eroded from highland basins, spread out from the major river mouths, providing very fertile soil.

The province of Esmeraldas is one of dense, luxuriant rainforest characterized by two main botanical strata: a high canopy of towering evergreen broadleaf species sprinkled with palms; and at eye level, clusters of giant ferns, shrubs, and vines. Among these are spectacular smaller plants such as orchids and bromeliads, which proliferate in the Amazonian forest.

South of Esmeraldas is a zone of deciduous scrub woodland that drops its leaves during the dry season. A narrow strip of tropical, semi-deciduous forest lies just north of Manta; and from here down to Guayaquil, this mangrove forest is broken only by the infertile scrubland of Santa Elena. Among the commercially used plants of the coastal forests are the balsa tree, source of the world’s lightest timber; the ivory-nut palm (tagua), used to make buttons; and the toquilla reed, from which the renowned Panama hat is manufactured.

The coastal region, which contains almost half of Ecuador’s 13 million people, is populated by a veritable melting pot of ethnic groups. Here, more than in the Sierra and the jungle, the trails of history incorporate all the colors of the rainbow. At the time of the Spaniards’ arrival, the centers of coastal indigenous habitation were Esmeraldas, Manta, Huancavilca, and Puná; these peoples were either exterminated outright, or else they mixed to the point where the distinctness between groups was completely extinguished.

Boy enjoying the beach at Galera.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

A century or so later, the Spanish-indigenous mixture (called mestizo) was infused with African blood as slaves were brought from West Africa, creating the mulatto (Afro-Hispanic mix) and montubio (indigenous-African mix) races. Indigenous Caribs were also shipped to Ecuador to work the plantations, adding a fourth element to this ethnic conglomeration. Mestizos comprise the majority of the coastal population, but the black influence is one of the region’s most interesting features, pervading all aspects of life.

From the Colombian border

A journey that begins in San Lorenzo 1 [map], in Ecuador’s northwestern corner, can only get drier. The sea is the town’s raison d’être, and fresh, salty breezes fill the potholed streets. The land around San Lorenzo is mostly mangrove swamp, navigated by motorized dugout canoes, while the town itself is frequently sodden with rainwater that has nowhere to run off. A road was recently constructed, linking San Lorenzo to Ibarra and Quito, and there is a bus service. However, many travelers who find themselves here may have come up the coast by boat. San Lorenzo used to mark one end of the spectacular, day-long train trip from Ibarra; unfortunately this line currently only runs from Ibarra to Primer Paso.

House with wraparound veranda in Esmeraldas province.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Despite its isolation, San Lorenzo can generate a certain amount of bustle. It possesses the best natural harbor on the Ecuadorian coast, and a hinterland still largely untouched due to its inaccessibility. The population has grown from 2,000 in 1960 – when, in the days prior to the discovery of oil in the Oriente, this was Ecuador’s El Dorado, the alluring, untapped frontier – to 20,000 today. Lumber traders have made profitable incursions into forests rich in mahogany, balsa, and rubber, creating industries and bringing itinerant laborers to this long-neglected outpost. However, illegal logging has put the forests under threat.

It should be noted that San Lorenzo has no immigration office, nor any official currency exchange, so crossing the Colombian border to Tumaco is near to impossible and, given the security risks in this part of Colombia, certainly not advisable.

African legacy

San Lorenzo has the feel of a town invented by Gabriel García Márquez. The descendants of people from distant continents have been washed up by history on this forbidding shore, and made the most of their displacement. African slaves transported in the 17th and 18th centuries were unloaded in Cartagena (Colombia) and marched southward to man the coffee, banana, and cacao plantations; less than half of this human cargo survived the privations of passage to reach their destinations.

Montañita streets.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The legacy of Africa lives on here today in the form of ancestor worship and the voodoo rituals of macumba, whereby spirits are summoned to cure and curse. Beneath the Latinized veneer of regular Sunday Mass lies an ancient belief in macabre spirits or visiones such as La Tunda, who frightens bad children to death and then steals their bodies, or El Rivel, who feasts on corpses.

African rhythms anchor the up-tempo beat of marimba music, which can be heard in San Lorenzo. Esmeraldeña marimba retains purer links with its origins than does the Colombian style, which has borrowed heavily from the Caribbean jingles of salsa and often resembles Western pop music. Talented musicians and dancers of both marimba styles can be seen rehearsing on Wednesday nights, and when they hit the downtown bars, San Lorenzo starts jumping. Men are said to come of age when they begin to andar y conocer; literally, “to walk and to know,” or “to travel and learn.” In local idiom, this commonly used phrase means “to strut,” and is heavily loaded with sexual innuendo.

To get to the coast road you have to go by boat from San Lorenzo to La Tola. Services are cheap and regular and take about 2.5 hours. En route to La Tola lies the island of La Tolita, an important ceremonial center from 500 to 100 BC. Tribal chiefs were buried here, their tombs filled with artifacts of gold, silver, platinum, and copper. In recognition of its historical significance, La Tolita has been declared an Archeological National Park and is undergoing extensive excavation. Like many such sites in South America, La Tolita has been savagely plundered by thieves, its treasures sold on the international black market. Fortunately, however, the government’s attention was attracted in time to salvage a substantial portion of the relics, and another gap in the jigsaw puzzle of ancient Ecuador is slowly being filled. An archeological museum has been erected on the site, showcasing finds from the digs and recovered artifacts.

Limones and around

Opposite La Tolita at the mouth of the Río Santiago is Limones (which must also be reached by boat). It is a small town of some importance as the center of the local lumber industry, but without a lot to offer tourists. Wood is floated downriver to the sawmill here, and processed for further distribution.

The lumber camps, isolated in the dense, upriver jungle, were quite notorious in their early days during the 1960s for a form of outpost exploitation worthy of the author Joseph Conrad. The mestizo owners forbade their workers – mostly morenos (a generic term for dark-skinned people in Latin America) – to leave camp. Instead, prostitutes and alcohol were shipped in to the camps each pay day; a kind of slavery with overpriced and monopolistic fringe benefits.

At a hairdressers in Puerto Lopez.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

This delta region is the home of the Cayapa or Chachi, who – along with the Tsáchilas of Santo Domingo – were the only indigenous coastal tribe to evade extermination by the Spaniards. In both cases, survival was due to the inaccessibility of their homelands. Today, the Cayapa number approximately 4,000. They are sometimes seen selling their finely woven hammocks and basketwork in the markets of Limones and La Tola – and occasionally Esmeraldas – but they prefer the privacy of Borbón and the inhospit-able upper reaches of the Río Cayapa. A turnoff on the La Tola–Esmeraldas road runs to Borbón, but this country is decidedly off the beaten track, and travel can be numbingly difficult, especially in the wet season.

A better option is to take a motorized dugout from El Bongo restaurant in Limones upriver to Borbón. From here expeditions continue up to Boca de Onzoles, at the confluence of the Cayapa and Onzoles rivers. In this far-flung village, a Hungarian émigré called Stefan Tarjany runs a comfortable lodge – Steve’s Lodge (Casilla 187, Esmeraldas; no phone) and organizes trips to the mission stations of Santa María and Zapallo Grande. He also arranges boat trips to the Reserva Ecológica Cotacachi-Cayapas, but the usual starting point for this trip is San Miguel, the last settlement on the river. It is advisable to check that these trips are still running before journeying to this remote location.

The reserve covers some 204,400 hectares (505,000 acres) and its habitat varies from lowland tropical forest, in this region, to cloud forest, to windswept plain, and accordingly has an enormous range of flora and fauna. It is also the home of the Cayapa, who continue to live in their traditional way, trying to avoid the encroachment of Western values and influences. The reserve receives protection from the Ecuadorian government and from international conservation organizations. Guided tours in dugout canoes can be arranged with the park rangers.

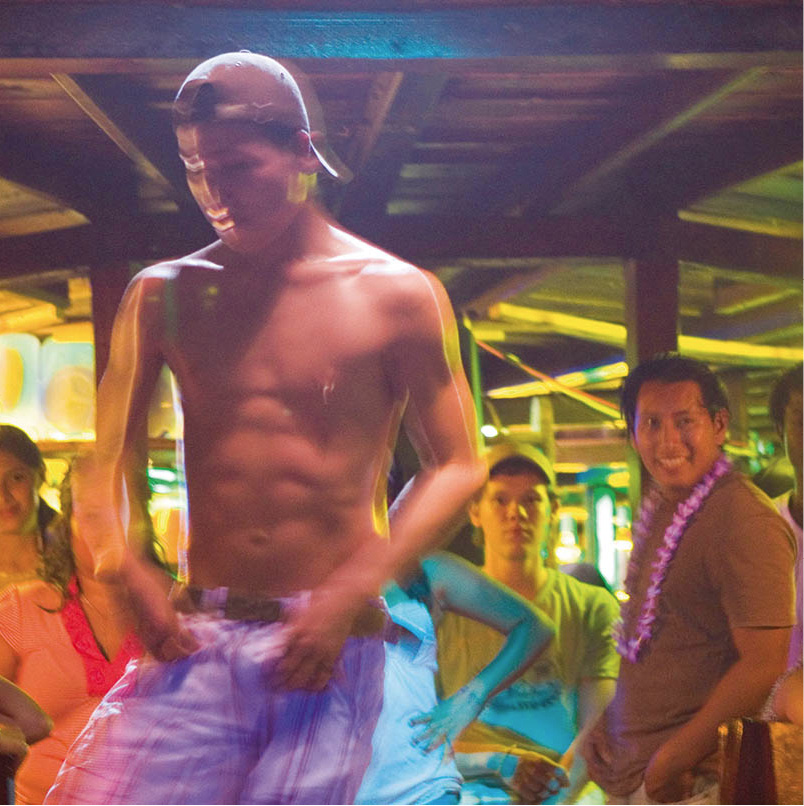

Dancing the night away in Atacames.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Travel in other parts of Ecuador is rarely as adventurous as in these alluring backwaters, which few visitors make the effort to explore. The Cayapa people’s counterparts in the Oriente – Stone Age tribes such as the Jivaro and the Huaorani – have received far greater international exposure, which in turn has attracted more tourists. This exposure may, however, prove beneficial as the search for oil in the Amazon basin is a much greater threat to indigenous lifestyles than anything the Cayapa are up against.

Tip

Though Esmeraldas city has been trying to shed its dangerous reputation, it is still somewhere to be circumspect, especially at night. Take taxis rather than walk after dark, and avoid anywhere away from the main streets of town. Special care should be taken in the market areas both day and night.

The road to Esmeraldas

The road from La Tola to Esmeraldas 2 [map] is rough and never ready: rancheros, which are open-sided trucks fitted with far too many wooden benches, take 5 hours to cover the 100km (60 miles); regular buses do the journey in 3 hours. The northern half of this road may suffer severe flooding during the wet season, but otherwise it is a carefree, breezy ride past cattle farms and swamps teeming with birdlife. A few small towns are strung out along the way, but offer little reason to pause.

It was near Esmeraldas that the conquistador Bartolomé Ruiz and company landed, the first Spaniards to set foot on Ecuadorian soil. Esmeraldas is named after the precious stone found in bountiful quantities in the like-named river, at whose mouth the city lies. The native Cara, who inhabited this area before migrating to the mountain basins around Otavalo during the 10th century, worshiped a huge emerald known as Umina. Today, the treasures are more industrial than geological: Esmeraldas is the major port of the north coast, whence timber, bananas, and cacao are shipped abroad. The 500km (300-mile) trans-Andean oil pipeline ends here, and the construction of an oil refinery has brought new jobs and money to the city.

The treatment of previously fatal tropical diseases has contributed significantly to the growth of Ecuadorian ports, notably Guayaquil, Manta, and Esmeraldas. The eradication of yellow fever from these towns early in the 20th century was the first step, followed by the discovery and availability of quinine as an antidote for malaria, which as recently as 1942 accounted for a quarter of all deaths in Ecuador. The treatment of tuberculosis, cause of almost one-fifth of deaths in Ecuador just a generation ago, completed the region’s health improvements, providing the basis for the international maritime trade, although the area is one of the poorest in the country.

Black capital

Esmeraldas’ population of nearly 120,000 consists of mostly mestizos and morenos, with a surprising minority of mountain indígenas looking forlorn and far from at home. Esmeraldas is the center of black culture in Ecuador. It is here that the visitor is most likely to encounter a full marimba band, complete with huge conga drums, led by the bomero, who plays a deep-pitched bass drum suspended from the ceiling. Esmeraldas is, like its music, a vibrant city that embodies the distinctive elements of coastal urban life. The people are gregarious and no-nonsense, playing with far greater enthusiasm than they work. Nothing is highbrow, all culture is popular, and most would rather watch the opposite sex sway by than observe a religious ritual. The energy level on the streets soars as the sun dips into the Pacific, and bars and restaurants – serving dishes of delicious cocado, fried fish in a spicy coconut sauce – fill to overflowing.

For the more cerebrally inclined, the Museo Arqueológico (Mon–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–1pm and 2–4pm; free) has exhibits on many of the region’s pre-Inca cultures: Bahía, Valdivia, Chorrera, and Tuncahuan, as well as some small golden masks from La Tolita. There is also the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (tel: 06-271 0393; Mon–Fri 8.30am–12.30pm and 2.30–6.30pm; free) with a collection of colonial and contemporary art, but do not be surprised if you are the only visitor. Discotheques far outnumber museums in Esmeraldas, which is a fair reflection of the hedonistic spirit of the ancient peoples whose suggestive figures are on display here.

Relaxing retreats

Everything about Esmeraldas province says “laidback.” For many visitors, the languid climate and the pleasant slowness of the pace of life is conducive to spending a quiet few days at a beach retreat or secluded backcountry lodge. Here are a few recommended destinations for your get-away-from-it-all holiday-within-a-holiday in Esmeraldas:

Playa Escondida (tel: 09-973 3368; www.playaescondida.com.ec) A shady, quiet retreat right on the seashore, and set in 40 hectares (100 acres) of ecological reserve, 3km (2 miles) west of Tonchigüe. This is not luxury, but being so close to nature makes up for that.

The Playa de Oro community, near the border of Reserva Ecológica Cotachachi-Cayapas runs a rustic jungle lodge (www.touchthejungle.org) with private bathrooms and mosquito nets. Jungle tours and meals are included.

Mompiche Beach Lodge (tel: 02-225 2488) has quite luxurious cabañas close to the beach, with hammocks to laze in and sea-kayaking tours of the nearby mangroves.

El Acantilado (www.hosteriaelacantilado.com), located on the edge of the beach, 1km (0.5 miles) south of Same, is a quiet oceanfront retreat with simple cabañas or suites set in a lush garden with a big swimming pool.

Golden sands and palm trees

To the immediate southwest of Esmeraldas begins a stretch of coastline containing the finest beaches in Ecuador. The beach suburb of Las Palmas is a more pleasant alternative to staying in the rather unattractive downtown area of Esmeraldas, but the beach is polluted and reported to be a dangerous place for tourists and single women. The road to the other, less visited beaches passes the Petro Ecuador oil refinery and a luxury hotel, the Hostal La Pradera (tel: 06-270 0212) – complete with swimming pool, tennis courts, and a statue of the Virgin of the Swan in a garden grotto – before reaching the coast.

Strolling along the beach near Atacames.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The road from Esmeraldas is reasonable and there is a bus service down the coast to Muisné. Mompiche, 127km (79 miles) south of Esmeraldas was, until recently, a sleepy fishing backwater. Now it’s become one of the most talked-about surf destinations in Ecuador. Around Mompiche are wonderful black-sand beaches, but boat tours out to the nearby Isla Portete cost around $5 and it’s here, on this small island, that you will find the region’s best surfing. There’s also good birdwatching here.

The small, friendly resort town of Atacames, 30km (19 miles) from Esmeraldas, is popular with Ecuadorian and foreign tourists alike. In recent years it has gained a reputation as a noisy party town, where the music blasts out 24 hours a day, particularly during the June–September high season. The town has blossomed into the largest resort on the north coast, with countless hotels, resorts, cabins, and lodges. Atacames has a cooperative of artisans, presided over by El Tío Tigre (Uncle Tiger), which manufactures and sells bracelets and necklaces of black coral, found just offshore to the south. Buying such artifacts cannot be encouraged, however, since in many areas the coral has been pillaged to the point of virtual extinction.

While the beach at Atacames looks harmless, there is a powerful undertow. There are no lifeguards, and the current sweeps some swimmers to their deaths every year. Sea snakes washed up on the beach pose another risk: they are venomous and should be avoided. A less avoidable problem is theft, which has been steadily increasing in Atacames in recent years. There have also been several reports of assault on the beach late at night, so solitary midnight strolls are not recommended. Despite these warnings, the probability of a visitor encountering any trouble remains slim.

Beach life at Same.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Some 6km (4 miles) farther south lies Súa, a small, beautifully located fishing village, somewhat more friendly than Atacames. The fishermen haul their catch right up onto the small beach, which immediately becomes an impromptu local market. The sky fills with seabirds such as frigates and pelicans, who do a fine job gobbling up fish heads and guts. While a stay in Atacames is chiefly a matter of relishing the elements, Súa offers glimpses of life in a small seaside town with its eye less on tourists than on the next catch.

Eat

The Hotel Súa has rooms with balconies and sea views. The -restaurant is recommended both for fish and a wide variety of other meals.

Luxury and adventure

A further 8km (5 miles) along the ocean road lies an unpaved side track to the beach of Same (pronounced “Sa-may”), perhaps the finest along this stretch. There is little here other than a collection of mostly expensive and tasteful hotels. Same does have the air of a place on the verge of overdevelopment, as it has become a resort for wealthy Quiteños who have erected an endless line of high-rise condos, but it remains the quintessential “away-from-it-all-in-comfort” destination.

Beach football at Galera in Esmeraldas province.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The completely undeveloped villages of Tonchigüe and Galera, both with lovely beaches nearby, lie a short distance west of Same. At this point, the road leaves the coast and cuts southward through undulating banana plantations before re-emerging at the shoreline opposite the island of Muisné, 83km (52 miles) from Esmeraldas. Motorized dugouts ply the short distance from the mainland to Muisné and, since few visitors bother to come this far from Esmeraldas for just another beach, Muisné exudes the alluring, timeless languor characteristic of any remote tropical island. The beaches here are enormous and empty; there is a handful of cheap, basic hotels and good seafood restaurants, and nothing more. The ghost of Robinson Crusoe may well haunt Muisné’s beaches; if you see another set of footprints in the sand, it must be Friday. Inland from Muisné there is an isolated community of native Cayapa, some of whom may be seen around town at the Sunday market.

Fact

Ecuador’s shrimp breeding industry has burgeoned in recent years, but it has been to the detriment of the coastal mangroves, which were cleared to build shrimp farms. You can see the last of the healthy mangroves around Same and Musine; and once you’ve observed the destruction the farms cause, you may think twice before you eat shrimps.

From Muisné to Cojimíes 3 [map], 50km (31 miles) to the south, there is no road. One or two motorized dugouts make the 2-hour journey each day, some continuing as far as Manta; the boats hug the coastline all the way, making it a safe and picturesque trip. An adventurous alternative is to head off under your own steam: the town of Bolívar, from where boats depart for Cojimíes, is about 23km (14 miles) from Muisné, making a feasible, if challenging, day’s walk. There are several rivers to be forded en route, but locating a ferry is usually easy, and an early start should bring you to Bolívar, where there are no hotels, in time to catch a boat to Cojimíes before dark. The wildlife along this pristine, largely uninhabited coastline is unsurpassed on Ecuador’s mainland shore: jellyfish and crabs proliferate, as does the full gamut of pelagic birds. Again, check the security situation before making this journey.

Colorful sun shelters on Canoa beach.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Cojimíes lies at the northern end of the road that follows the coast down to Manta. It is a quiet and welcoming town, the site of a pre-Columbian settlement that still awaits comprehensive excavation. Transportation connections are delightfully whimsical: the unpaved road is impassable in the wet season, and the daily rancheros usually run along the beach in a race against the rising tide. Just south of Pedernales, the road crosses the equator – marked by a small monument – and then forks. The left-hand turn runs through more farms and plantations to Santo Domingo de los Colorados, while the coastal road continues on to the small market town of Jama. Another 50km (31 miles) south lies Canoa. This peaceful village is center of a fast-developing deep-sea fishing industry and is fast becoming a backpacker buzzword thanks to its location alongside one of the widest, loveliest beaches in the country. There are some interesting caves and rock formations nearby.

Scenic roadway

The inland loop through Santo Domingo returns to the coast at Bahía de Caráquez, and is a refreshing change for anyone suffering from an overdose of empty, sun-drenched beaches. This route through the heartland of Manabí province is among the most scenic in the coastal region, and passes several interesting stop-offs. Past more banana plantations and cattle farms, the road runs to El Carmen, whereafter green hills rise from the plain. Much of Manabí, particularly the southern area, suffers a dearth of rainfall, due primarily to the lifeless winds of the Humboldt Current. Nevertheless, the province is the agricultural core of Ecuador, with coffee, cacao, rice, cotton, and tropical fruits cultivated widely. The Poza Honda Dam, built mostly with German finance, is fed by the Río Portoviejo and irrigates large areas of previously uncultivatable lowlands.

Chone (population 41,000) prospers on the strength of these industries, as well as the manufacture of leather saddles and a type of straw hat called a mocora. The banks of the Río Chone, twisting through the undulating Cerros de Bálsamo (Bálsamo Hills), sustain increasing numbers of shrimp farms, an indication of Ecuador’s modern industrial diversification, although they have also led to the destruction of mangrove forests. The road climbs to a vantage point offering splendid views of Bahía de Caráquez and the mangrove islands dotting the bay, and then slides down to the coast.

Fishermen on the beach at San Vincente.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The resort village of San Vicente stands at the mouth of the Río Chone, opposite Bahía de Caráquez. The recently constructed church of Santa Rosa has an ornate, eye-catching facade and mosaic and glasswork by the Ecuadorian artist Pelí, but otherwise there are few diversions except for the beach. About 70km (44 miles) inland along a makeshift road is the important archeological site of San Isidro. The prehistoric inhabitants of San Isidro excelled in the art of ceramics, and imitations of their beautifully crafted figurines are today sold throughout Ecuador.

Tip

To learn more about eco-projects in and around Bahía de Caráquez, visit www.planet-drum.org.

Banana centers

Bahía de Caráquez 4 [map] is named after the native Cara who, legend has it, came “by way of the sea” and settled in this bay. Formerly an important export center for bananas and cacao, Bahía entered semi-retirement when the focus of banana exporting – in which Ecuador continues to lead the world – shifted south to Guayaquil and Machala. The cacao industry, in turn, has been steadily declining since it was struck down by a crippling blight in 1922–3, at which time Ecuador was the world’s foremost producer. In 1999 Bahía became an eco-city in recognition of its strong green movement and the efforts made by the local community to rebuild the city in an ecologically sound way after the disastrous El Niño floods and earthquakes of 1997–8. A stroll along the palm-fringed riverside malecón (pier), past rows of stately old mansions, some of them in Victorian “gingerbread” style, reveals remnants of former prosperity. Nevertheless, Bahía’s strategic river-mouth location ensures its continued existence as a minor port, and it remains the largest coastal town – with 20,000 inhabitants – between Esmeraldas and Manta.

Much of Bahía’s energy today is devoted to tourism: unlike many of Ecuador’s north-coast towns, it is easily accessible on good roads from Quito, and is one of the most popular resorts in the country. While there are few noteworthy sights in the town, it does offer some simple pleasures. An ascent of La Cruz hill is rewarded by sweeping views of the river and coastline, and a sojourn to a riverside café affords relief from the burning sun. There is also a collection of pre-Columbian Manabí pottery in the Casa de Cultura. Ferries across to San Vicente depart frequently, providing a means of transportation as well as a scenic way to cool off.

From Bahía, tours can be arranged to the Río Muchacho Organic Farm. While many farms in the area have destroyed the ecosystem and rendered the land desert-like, Río Muchacho is covered with vegetation. You can go horseback riding around the farm or try shrimp-fishing. Multiple-day tours can include Spanish lessons and the opportunity to interact with the Montubios, the local indigenous people. Beach tours are also available on open-sided chiva buses, which tour the bay, stopping at a number of sites of interest.

Worker at Río Muchacho organic farm, near Bahía de Caráquez.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Venturing slightly farther afield, launches can be hired to visit Isla de los Pájaros and Isla Corazón in the bay. These two islands, as the former’s name indicates, have raucous seabird colonies. A boardwalk has been constructed on Isla Corazón, which leads right over the mangroves.

Some 20km (13 miles) south of Bahía de Caráquez are the friendly, peaceful fishing villages of San Clemente and San Jacinto; driving along the beach at low tide may look tempting, but is inadvisable as many cars have died a watery death here. Instead, follow the Portoviejo road and turn off just before Rocafuerte; this route leads to San Jacinto, and on to San Clemente 5km (3 miles) away to the north. Along this road, which is notable for the giant ceiba trees lining the way, lies Crucita, a beach resort and a perfect spot for paragliding. Shortly thereafter, and just 15km (9 miles) east of Manta, is the fishing village of Jaramijó. This is the site of an extensive pre-Columbian settlement and where Eloy Alfaro, one of Ecuador’s best-remembered presidents, lost an important naval battle against conservative forces in December 1884: the wreck of his ship, the Alajuela, can still be seen. Also near San Clemente, is the archeological site of Chirije which dates back to the Bahía culture (500 BC–AD 500). A small museum on the site has finds from the ongoing excavations of the area.

Fact

The ancient city of Manta had a population of 20,000 and traded with the coastal peoples of Mexico and Peru.

Pre-Columbian hedonists

For 1,000 years prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, Manta 5 [map] was the center of one of Ecuador’s pre-eminent indigenous cultures. It was known as Jocay – literally, “fish house” – by the local inhabitants, whose exquisite pottery was decorated with scenes of daily life. And what a life it was. The exuberant hedonism of contemporary coastal Ecuadorians can be traced back directly to the ancient Manteños with their pervasive fertility cult and enjoyment of coca. Their concept of physical beauty was expressed by the practice of strapping young children’s heads to a board in order to increase the backward slope of their chins and foreheads. The desired effect was an exaggeration of the rounded, hooked nose.

The Manteños sacrificed their prisoners of war by ripping out their still-beating hearts. Their culture was part-settler, part-wanderer, as they cultivated fruit and vegetables while also trading with highland tribes – their source of precious metals – and navigated the ocean in rafts and dugouts as far as Panama and Peru, and possibly the Galápagos Islands. Their skill extended to the arts of stonemasonry, weaving, and metalwork; in short, a cultural sophistication of great breadth and depth.

The Spaniard Francisco Pacheco founded the modern settlement of Manta just 10 days before Portoviejo in 1535. Nine years earlier, however, his fellow countryman Bartolomé Ruiz had encountered a balsa sailing raft with 20 Manteños aboard: 11 of them had leapt into the sea in terror, while the remaining nine served as translators before being set free. Perhaps this rare instance of Spanish tolerance has contributed to the unique character of modern Manta, for it is the most relaxed and habitable city of the entire coastal region.

In its previous incarnation as Jocay, the main thoroughfare of Manta was lined with statues of the chieftains and head priests. The Catholic Church ordered its place to be taken by inoffensive jacaranda and royal poinciana trees. Today, with a population of approximately 180,000, Manta is a major seaport, with coffee, bananas, cotton textiles, and fish comprising the bulk of the exports. For all this, the city feels much smaller than similarly sized Esmeraldas, the pace of life being much slower. Large numbers of Ecuadorian tourists vacation here.

Manta is divided by an inlet into a downtown and a resort district, the latter called Tarqui. Along the expansive Tarqui Beach, local fishermen unload and clean their catch – tuna, shark, dorado, eel, and tortoise – whipping the attendant gulls and vultures into aerial frenzy. A towering statue of a Manabí fisherman overlooks the proceedings, noticing few material changes from earlier times.

Stall in Manta’s fish market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Museo Banco Central (Tue–Fri 8.30am–5pm, Sat 10am–6pm) houses the finest collection of Manteño artifacts in Ecuador and is well worth a visit. Manta’s outdoor theater is the venue for occasional performances, especially during the agriculture and tourism exposition held each October. Playa Murciélago is an unprotected surfing beach a few kilometers west of town, site of the comfortable Hotel Manta Imperial. In Tarqui, the Hotel Haddad Manabí, dating from 1931, offers central accommodations with a slight touch of faded grandeur.

Panama Hats

US soldiers wore them, prohibition gangsters loved them, but do these coveted, tropical-chic accessories have a future?

Montecristi is the capital of Panama hat-making. For 150 years the best superfinos have been woven in this peaceful, nondescript town, and it is here that tourists come to buy the genuine article directly from the weavers’ hands. Why are these world-famous sombreros called Panama hats if they come from Montecristi? A mistake, apparently, attributed to some 19th-century gold-miners who forgot where they bought their innovative headgear.

The Panama hat production trail begins in the low hills west of Guayaquil, a region cooled by the sea breezes of the Humboldt Current, and where rainfall is plentiful but not excessive. In these conditions, the Carludovica palmata – named after King Charles IV and his wife Louise by two Spanish botanists in the late 18th century – thrives.

Today the plant is cultivated in fields divided according to the families’ seniority in the trade. The stalks of the plant can grow as high as 6 meters (20ft), but it is the material inside the stalks, the new shoots containing dozens of very fine fronds, each about a meter long and a few millimeters wide, that is used. These fronds are boiled in water for an hour and sun-dried for a day. The procedure is repeated to ensure maximum strength when woven.

Works of art

The finest weaving is done at night or on dull days, as direct sunlight makes the fronds too brittle, and hot sweaty hands don’t produce tight weaves. Women and children make the best hats, because their fingers, being smaller, are more agile. A superfino – as the best hats are called, those most tightly woven with the thinnest, lightest straw – takes up to three months to complete. The test of a true superfino is that it should, when turned upside down, hold water without any leakage. It should also fold up to fit neatly in a top pocket without creasing.

No one knows exactly how long straw hats have been woven in Ecuador, but the craft certainly preceded the Spanish conquest. The conquistadores were impressed by the headgear worn by the indigenous inhabitants of Manabí province, and adapted it for their own use.

A few of the Panamas were sent to the United States in the late 18th century. Then in the Spanish-American War of 1898, when the hats were considered ideal headgear for soldiers, the export market to the US really took off. The hats first hit Europe in 1855 at the World Exposition in Paris, and, as illustrated by many of Renoir’s paintings, they soon became a debonair item of contemporary fashion.

Chicago chic

America fell in love with the Panama, and for the next 50 years kept the industry going. The gangsters of the Prohibition period took such a shine to them that the Manabí manufacturers still call the wide-brimmed variety El Capone.

The industry peaked in 1946, when 5 million hats were exported, constituting 20 percent of Ecuador’s annual export earnings. In those days every household in Montecristi produced top-quality Panamas, but numbers have now dwindled to a handful. The international demand has fallen steadily since the early 1950s. China and Taiwan now produce cheaper imitations that are sufficiently like the genuine item to satisfy all but the most discerning, and many of the weavers of Manabí now earn their living by making mats and wickerwork furniture.

Panama hat shop, Montecristi.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Ecuador’s “Panama” hat

Straddling the highway between Manta and Portoviejo is the deceptively non-descript town of Montecristi 6 [map], for more than a century the home of the renowned Panama hat. Until recently, the majority of Montecristi’s 9,000-odd inhabitants were engaged in the weaving of these remarkable headpieces, made from the straw fronds of the Carludovica palmata. Large numbers of them still are, but Montecristi has had to move with the times, and some have switched to making fine wickerwork furniture and decorations. It is the quintessential cottage industry and many houses contain a rudimentary factory and showroom. The lack of any signs of wealth in Montecristi is sad testimony to the inequitable distribution of the industry’s hefty profits. Like Portoviejo, to the northeast, Montecristi owes its existence to pillaging pirates: in 1628, a group of Manteños left the coast in search of an inland refuge following pirate raids. Their colonial-style houses, now in a state of chronic disrepair, line the quiet, dusty streets and, in combination with the non-mechanized weaving, this physical neglect creates the air of a town stuck in another time.

The cathedral at Montecristi contains a statue of the Virgin that has supposedly worked several miracles.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Montecristi’s religious atmosphere is similarly dated: the beautiful church contains a famous statue of the Virgin to which several miracles were once attributed. And Montecristi’s favorite son is now long dead: Eloy Alfaro, president of Ecuador at the turn of the 20th century and a committed liberal reformist, was born here. His statue overlooks the main plaza, and his house is now a mausoleum, with his library and many personal effects on display. Almost alone among towns in coastal Ecuador, Montecristi survives as a relic, an impression heightened by the sight of modern-day tourists and Panama hat dealers roaring into town in search of a bargain.

Eat

If you are into fruit salads and smoothies, try La Fruta Prohibida on Avenida Chile in Portoviejo.

Portoviejo

From Montecristi it is only 24km (15 miles) to Portoviejo 7[map] , a town with a long history. In fact, it was one of the earliest Spanish settlements in Ecuador, founded on March 12, 1535, just three months after Benalcázar re-founded Quito atop abandoned Inca ruins. Guayaquil, founded in January 1535, was the first Spanish coastal community, but the local people, based on the nearby island of Puná, repeatedly launched marauding raids of such ferocity that alternative sites were sought.

The original settlement, founded by Francisco Pacheco on the orders of Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro, was, as its name (“Old Port”) suggests, located on the coast. The omens, however, were far from auspicious: in 1541, a fire destroyed the town, and 50 years later the local indigenous population staged a fearsome uprising. Finally, when English pirates ravaged the port in 1628, it was decided that a spot farther inland would be out of harm’s way. Since then, Portoviejo has existed in the shadow of Manta, though as capital of Manabí province it remains an important administrative and educational center. Its population has recently topped the 170,000 mark, most of which is engaged in commerce, industry, and the rich agricultural pickings of the hinterland. Portoviejo’s bustling streets are prettily bordered with rows of trees and flowering shrubs, and a stroll through the Parque Eloy Alfaro is perhaps the most pleasing pastime. Opposite the park is one of Ecuador’s starkest modern cathedrals; beside it stands a statue of Pacheco, the city’s founder.

There are two museums: the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, with a collection of traditional musical instruments; and the Museo Arqueológico, which is not as good as its counterpart in Manta. Portoviejo has a few old colonial buildings still standing, but otherwise little testimony to its long and tumultuous history.

Leaving Portoviejo, go back the way you came for 14km (9 miles), then turn off the Guayaquil road to the village of La Pila, which is an interesting stop-off. In the wake of the discovery of exquisite pre-Columbian ceramics in the area, the resourceful inhabitants of La Pila began producing indistinguishable imitations to cash in on their forebears’ artistry. Nowadays they have embraced originality and appear to have inherited not only the enterprise but also the considerable artistic skill of their ancestors.

Playing pool in Puerto López.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

In contrast, Jipijapa – a town of 30,000 inhabitants situated another 40km (25 miles) along the highway to Guayaquil – appears to have been swallowed up by Ecuador’s flourishing agricultural industries, particularly coffee and cotton. At Jipijapa, a side road climbs into the damp, luxuriant hills of southern Manabí before descending to the coast near Puerto Cayo, a fishing village with pristine beaches.

A large tract of the surrounding area was designated the Parque Nacional Machalilla in 1979. It protects a 55,000-hectare (135,910-acre) expanse of tropical dry forest, which is home to a wide variety of bird and animal life, as well as a stretch of coast and two islands. Some 15km (9 miles) offshore is Isla de la Plata, an ancient Manteño ceremonial center currently undergoing excavation. The island is named for an incident in the late 16th century, when Sir Francis Drake captured a silver-laden galleon and made camp on the island to tally his spoils. Recently, there have been a number of archeological finds from pre-Columbian times. Today it is inhabited only by sea turtles, blue-footed boobies, and a number of frigate birds such as the albatross, and can be reached by hired motorboat from Puerto Cayo; a trip of two hours. Look out for shells of the spondylus oyster, which in pre-Columbian times served as a unit of currency, and as such was regularly interred in the tombs of tribal chieftains. There is good diving and snorkeling here as well, and a number of agencies in Puerto López can provide gear and transportation.

You can enter the park from the coast road, or from the Manta to Guayaquil highway south of Jipijapa. Park admission costs $15 for the mainland parks or for Isla de la Plata, or $20 for both (ticket valid for five days), and tickets can be purchased at the park office in Puerto López (Alvaro and Moreno; daily 7am–6pm) or at the park.

Tip

Parque Nacional Machalilla is the only coastal park in Ecuador, and it protects varied habitats including tropical beaches and coastline, cloud forests, and tropical dry forests, as well as over 350 species of bird together with monkeys, anteaters, lizards, iguanas, and deer.

Continuing south, the well-worn coast road passes through Machalilla 8[map] , the center of the culture of the same name that flourished between 1800 and 1500 BC. It is rich in archeological remains, especially in the vicinity of Salaite and Agua Blanca, where there is a small archeological museum. A pleasant 45-minute walk from Machalilla brings you to the deserted horseshoe beach called Los Frailes (the Friars). About 10km (6 miles) further south, fleets of heavily laden fishing boats dock in the village of Puerto López each afternoon at about 4pm, and the skippers sell their catch there and then.

Strolling along a Pacific coast beach.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Whale-watching

Dusty, sleepy Puerto López is at first glance perhaps not a typical visitors’ paradise. That all changes between June and September, however, when it becomes the whale-watching capital of Ecuador. During these months, humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) migrate with the Humboldt Current from the Antarctic to mate and give birth to their calves in the warm, shallow waters around Machalilla National Park. Humpback whales, which can reach 16 meters (53ft) in length and weigh 30–40 tonnes, are the most acrobatic of the bigger whales, often breaching out of the water and slapping the water’s surface dramatically with their large pectoral fins and tail flukes. The excitement becomes palpable in town during whale-watching season when many professional – and some fly-by-night – operators open up shop and loudly tout their tours to make the best of the short, but lucrative, season. Most operators offer whale-watching tours with snorkeling or diving and park excursions. Book well ahead. Recommended operators include: Exploramar, with 8–12-person boats and PADI divemasters (tel: 05-230 0123; www.exploradiving.com), and Mantaraya, which also has an excellent lodge (tel: 02-336 0887; www.mantarayalodge.com). Puerto Cayo is also becoming another centre for whale-watching along this part of the coast and has a handful of operators that offer good boat tours.

From Salango to Montañita

About 5km (3 miles) south of Puerto López is Salango, a small fishing village close to a site where dozens of people took part in the largest archeological dig in the country, providing insights into the fragmentary history of pre-Columbian Ecuador. The relics of a host of successive cultures – Valdivia, Machalilla, Chorrera, Engoroy, Bahía, Guangala, and Manteño – that inhabited this fertile stretch of coastline as early as 2000 BC were painstakingly recovered. A museum here is filled with artifacts found in the area.

Ask most Ecuadorians what their favourite beach getaway and they will most likely tell you about Ayampe, about half way along the road from Salango to Montañita. It’s a relaxed, and undeveloped fishing village, but at the rustic Finca Punta Ayampe (tel: 09-189 0982; www.fincapuntaayampe.com) you can nevertheless stay overnight and take surfing lessons.

Mouth-watering ceviche.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Around 23km (14 miles) south from here, Montañita, which for many years was simply a locally known surf spot, has blossomed into the largest surf resort in the country, one of Ecuador’s biggest backpacker hangouts and very much part of the hip traveler “scene.” Many cheap hotels, jewelry stands, restaurants, and bars and clubs line the cluster of streets. The town is a good base for arranging tours into Machalilla National Park, Isla de Plata, and for whale-watching, paragliding, or kite-surfing. The beach is crowded during the summer months and filled with umbrellas, beer vendors, surfers, and carts selling ceviche de ostra (oyster ceviche). More upscale accommodations can be found at the north end of the beach, known as Baja Montañita, and in the town of Olon a few kilometers north. Some 3km (2 miles) south of Montañita is Manglaralto, which is a small, cozy town with several small yet decent hotels offering great value for money, such as Hotel Manglaralto just off the beach beside the central park.

Surfer in Montañita.

Corrie Wingate