Within the space of a century, successive invaders – the Incas and the Spaniards – swept across the country in great waves of destruction, each seeking to remake it in their own image. Their impact is reflected in the varied ethnicity of the Ecuadorian people – 7 to 10 percent indigenous, 78 percent mestizos (mixed European-indigenous blood), 11 percent criollos (locally born Europeans), and 5 percent the descendants of black Africans. Their legacy of brutal exploitation constitutes an ongoing struggle for modern Ecuadorians.

A 19th-century illustration of the scientist Alexander von Humboldt watching the sky.

Mary Evans Picture Library

Sierra cultures

The land that is now Ecuador was first brought under one rule when the Incas of Peru invaded in the middle of the 15th century. By this time, the dazzling cultures of Manta and La Tolita on the Ecuadorian coast had flowered and faded, while an increasingly powerful series of agricultural societies had divided the region’s highlands among them.

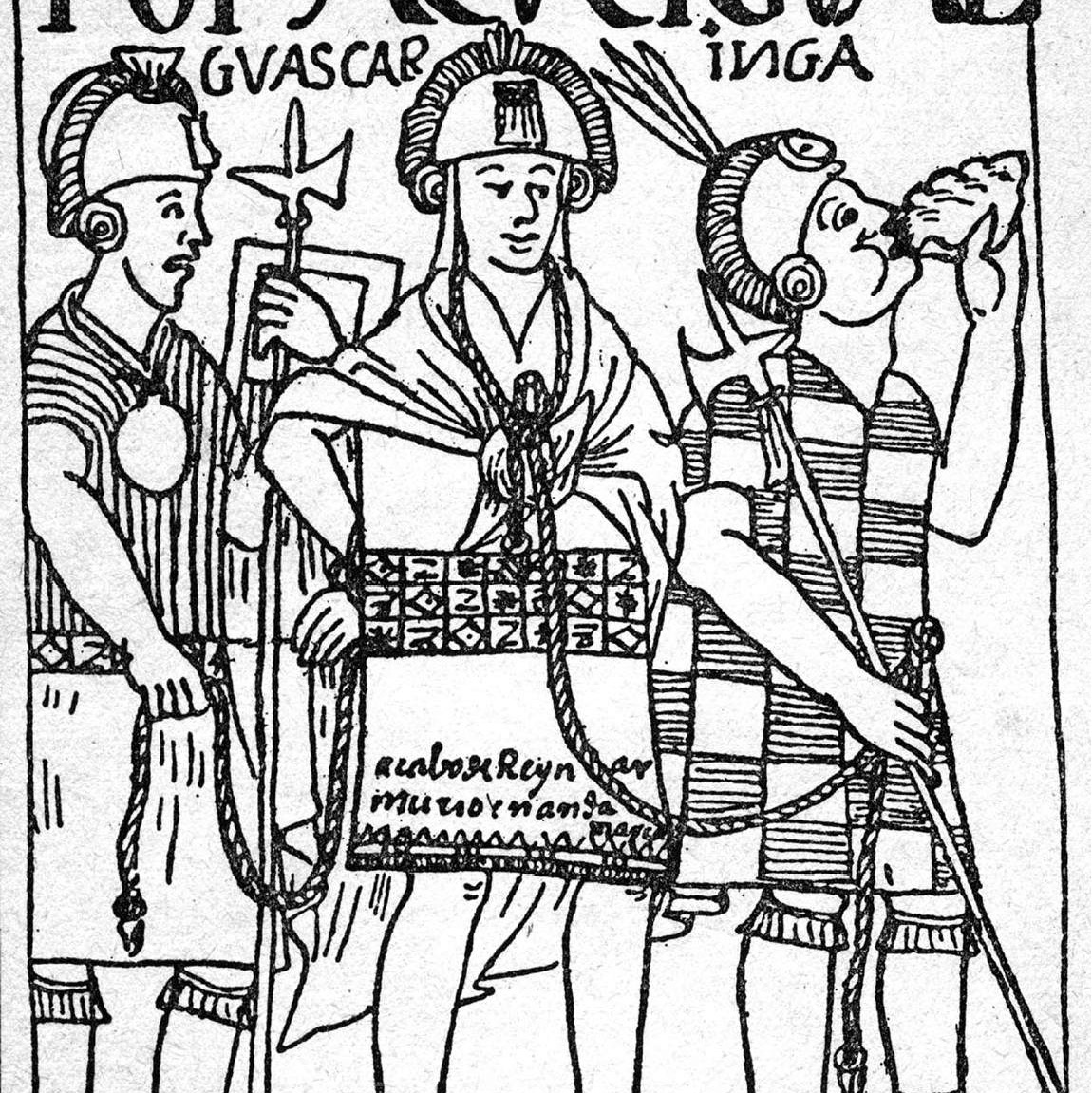

The garotting of Atahualpa.

Getty

The greatest were the Cañaris, who inhabited the present-day towns of Cuenca, Chordaleg, Gualaceo, and Cañar. Theirs was a rigidly hierarchical society. Only the Cañari elite were allowed to wear the fine, elaborate gold and silver produced by their metalsmiths. Among the Cañari artifacts, figures of jaguars, caymans, and other jungle animals predominate, showing their strong links with Amazonian groups.

In the north, archeological evidence points to a more fragmented rule, though often still called “the Kingdom of Quito.” Research has all but dispelled the existence of the legendary Shyri and Duchicela dynasties. Rather than a centralized state, local chieftains formed periodical military alliances, possibly giving the attacking Incas the impression of centralized rule under the Quitu-Cara tribe based around Quitu, particularly in light of their fierce defense of their independence. The city was already an established commercial center on the site of present-day Quito

Tribes in the area included the Yumbos, traders between the Andes and the coast, Cochasquies, Cayambis, Otavaleños, and the Pasto on the present-day border with Colombia. The pre-Inca Cochasquí pyramids north of Quito are among Ecuador’s most important archeological ruins. Locals were well aware of the equator as “the path of the sun.” Their economy was based on spinning and weaving wool, and there was a traveling class of merchants who traded with tribes in the Amazon Oriente. Farther south, the Puruháes, ferocious warriors based around Ambato, were more closely related to the Cañaris.

Famous Inca masonry at the ruins of Ingapirca.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Inca invasion

Into this landscape of tribal identity marched the Incas – literally, “Children of the Sun” – who were to be the short-lived precursors of the Spaniards. Although established in the Peruvian Andes from the 11th century, it was not until about 1460 that they attacked the Cañaris, with the ultimate objective of subjugating the Kingdom of Quitu. Ecuador became brutally embroiled in imperial ambitions as armies dispatched from distant capitals turned the country into a battlefield.

The Cañaris fought valiantly against all odds for several years before being subdued by the Inca Tupac Yupanqui. His revenge severely depleted the indigenous male population: when the Spanish chronicler Cieza de León visited Cañari territory in 1547, he found 15 women to every man. Inca occupation was focused on the construction of a major city called Tomebamba on the site of present-day Cuenca. It was intended to rival the Inca capital of Cuzco, from where stonemasons were summoned to build a massive temple of the sun and splendid palaces with walls of gold.

The capture of Huascar during the Incas’ bitter civil war.

Mary Evans Picture Library

But by the time Cieza de León arrived, Tomebamba was already a ghost town. He found enormous warehouses stocked with grain, barracks for the imperial troops, and houses formerly occupied by “more than two hundred virgins, who were very beautiful, dedicated to the service of the sun.” At nearby Ingapirca, the best-preserved pre-Hispanic site in Ecuador, the Incas built an imposing complex that also served as temple, storehouse, and observatory.

Legendary dynasties

According to local lore, the Caras – who, it is thought, arrived in the Andes by traveling upriver from the areas around Esmeraldas and Bahía de Caráquez on the coast – were under the rule of the Shyri (“lord”) dynasty. They then conquered an area including Cayambe and Otavalo in the north down to Latcunga and Ambato in the south. The Puruháes, ruled by the Duchicela family, intermarried with the Shyri in the 14th century, so creating a “Kingdom of Quito,” the core of a pre-Hispanic Ecuadorian nation. Belief in this realm is still widespread, though historians as early as the 19th century began to question its very existence.

Inca conquest along the spine of the Andes continued inexorably. Quitu, which had fallen by 1492, became a garrison town on the empire’s northern frontier and, like Tomebamba, the focus of ostentatious construction. Battles continued to rage: for 17 years the Caras resisted the Inca onslaught before Huayna Cápac, Tupac’s son, captured the Caras’ capital, Caranqui, and massacred thousands.

The Incas at war were a fearsome sight. Dressed in quilted armor and cane or woolen helmets, and armed with spears, champis (head-splitters), slingshots, and shields, they attacked with blood-curdling cries. Prisoners taken in battle were led to a sun temple and slaughtered. The heads of enemy chieftains became ceremonial drinking cups, and their bodies were stuffed and paraded through the streets.

The Incas made battle drums from the stomachs of their enemies. By 1492, they had conquered much of present-day Ecuador, ending with the epic battle that gave Yahuarcocha, or blood lake, near Ibarra its name.

Imposing the new order

The Incas introduced their impressive irrigation methods and some new crops – sweet potatoes, coca, and peanuts – as well as the llama, a sturdy beast of burden and an excellent source of wool. The chewing of coca, previously unknown in highland Ecuador, soon became a popular habit. The Imperial Highway was extended to Quitu, which – although 1,980km (1,230 miles) from Cuzco – could be reached by a team of relay runners in eight days. Inca colonization also brought large numbers of loyal Quechua subjects from southern Peru, and many Cañaris and Caras were in turn shipped to Peru as so-called mitimaes. Loyalty to the Inca, with his mandate from the sun, was exacted through the system of mita – imperial work or service – rather than taxation. As large areas came under centralized control for the first time, a nascent sense of unity stirred; but it was an alien and oppressive regime, attracting little genuine loyalty.

The Ecuadorian natives who suffered Inca domination were proud, handsome peoples. Cieza de León spoke of the Cañaris as “good-looking and well grown,” and the native Quiteños as “more gentle and better disposed, and with fewer vices than all Indians of Peru.” Tupac Yupanqui married a Cañari princess, and Huayna Cápac, in turn, the daughter of a Quitu aristocrat. This was to play a crucial part in the collapse of the empire, for Huayna Cápac, seeking to unite his domain through marriage, achieved just the opposite.

Huayna Cápac had been born and raised in Tomebamba; his favorite son, Atahualpa, was the offspring of the Quitu marriage and heir to the northern quarter of the empire. Atahualpa’s half-brother Huascar was descended from Inca lineage on both sides, and thus the legitimate heir. In 1527, Huascar ascended the Cuzco throne, dividing the empire. Civil war soon broke out, and continued for five years before Atahualpa defeated and imprisoned Huascar after a major battle near Ambato.

Atahualpa, an able and intelligent leader, established the new capital of Cajamarca in northern Peru. But the war had severely weakened both the infrastructure and the will of the Incas, and by a remarkable historical coincidence, it was only a matter of months before their death-knell sounded.

This illustration shows Spanish conquistadors laying waste to the native peoples.

Getty

The bearded white strangers

Rarely have the pages of history been stalked by such a greedy, treacherous, bloodthirsty band of villains as the Spanish conquistadors. With their homeland ravaged by 700 years of war with the Moors, the Spanish believed they had paid a heavy price for saving Christian Europe from Muslim domination. When news reached Spain of the glittering Aztec treasury, snatched by Cortés in 1521, it fired the imaginations of desperate owners of ruined lands – and the Church – and spawned dreams of other such empires in the New World.

The first conquistadors to set foot on Ecuadorian soil landed near Esmeraldas in September 1526. They had been dispatched from Colombia by Francisco Pizarro to explore lands to the south. The party, led by Bartolomé Ruiz, discovered several villages of friendly people wearing splendid objects of gold and silver, news of which prompted Pizarro himself, with just 13 men, to follow a year or so later. Near Tumbes, he found an indigenous settlement whose inhabitants were similarly adorned, and so planned a full-scale invasion. Late in 1530, having traveled to Spain to secure the patronage of King Charles I (or Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor) and the title of governor and captain-general of Peru, Pizarro – this time with 180 men and 27 horses – landed in the Bay of San Mateo near Manabí.

Into the Amazon

A sign on Quito’s cathedral and a monument in front of the church at Guápulo honors Ecuador’s proud discovery of the Amazon basin.

Once Quito had been settled, the conquistadors began to seek new lands and adventures. Tales of El Dorado and Canelos (the Land of Cinnamon, supposedly to the east) filled the air. Francisco Pizarro appointed his brother Gonzalo to lead an expedition to find these magical destinations.

The search for El Dorado

On Christmas Day, 1539, Gonzalo Pizarro left Quito with 340 soldiers, 4,000 indígenas, 150 horses, a flock of llamas, 4,000 swine, 900 dogs, and plentiful supplies of food and water. Surviving an earthquake and an attack by hostile natives, the expedition descended the Cordillera. At Sumaco on the Río Coca they were joined by Francisco de Orellana, who had been called from his governorship of Guayaquil to be Gonzalo’s lieutenant.

Hacking their way through dense, swampy undergrowth, and hampered by incessant heavy rain, they were reduced to eating roots, berries, herbs, frogs, and snakes. The first group of people they met denied all knowledge of El Dorado, so Gonzalo had them burned alive and torn to pieces by dogs. They met another group who spoke of a city, supposedly rich in provisions and gold, just 10 days’ march away at the junction of the Coca and Napo rivers.

A large raft was constructed, and 50 soldiers under Orellana’s command were dispatched to find the city and return with food: already 2,000 indígenas and scores of Spaniards had starved to death. Hearing nothing of the advance party after two months, Gonzalo trekked to the junction, but there was no city. The pragmatic natives had very sensibly lied to save their skins. In early June, 1542, the 80 surviving Spaniards from Pizarro’s group staggered into Quito, “naked and barefooted.” By then, Francisco de Orellana was far away. The brigantine’s provisions were exhausted by the time the party reached the river junction: sailing back upstream against the current was impossible, and the difficulties of blazing a jungle trail would have killed the weary men. Hearing the call of destiny and whispers of El Dorado across the wilderness, Orellana sailed on.

For nine months the expedition drifted on the current. Crude wooden crosses were erected as they progressed, purporting to claim the lands in the name of the Spanish king. They encountered many indigenous tribes: some gave them food and ornaments of gold and silver; others attacked them with spears and poisoned arrows, claiming many Spanish lives. On one occasion 10,000 tribespeople are said to have attacked them from the river banks and from canoes, but the Spaniards’ arquebuses soon repelled them. They heard frequent reports of a tribe of fearsome women known as “Amazons,” who lived in gold-plated houses. Near Obidos, the “Amazons” attacked. They were “very tall, robust, fair, with long hair twisted over their heads, skins round their loins, and bows and arrows in their hands.” From this report, the great South American river and jungle area took its name.

Finally, in a lowland area with many inhabited islands, Orellana noticed signs of the ebb of the tide and, in August 1541, sailed into the open sea. For the first time, Europeans had traversed South America. Today, if you want to emulate this experience in style and comfort, you can take a cruise aboard the Manatee Amazon Explorer, a comfortable riverboat which began operating in 2002 on the Río Napo from the town of Francisco de Orellana, colloquially known as Coca.

Gonzales Ximenes de Quesada searched (without success) for El Dorado.

Mary Evans Picture Library

For two years the conquistadors battled against the native peoples and against the treacherous terrain of mosquito-infested swamps and jungles, and frozen, cloud-buffeted mountain passes. Arriving exhausted in Cajamarca in November 1532, they formulated a plan to trap the Inca Atahualpa. At a pre-arranged meeting, the Inca and several thousand followers – many of them unarmed – entered the great square of Cajamarca. A Spanish priest outlined the tenets of Christianity to Atahualpa, calling upon him to embrace the faith and accept the sovereignty of Charles I. Predictably, Atahualpa refused, flinging the priest’s Bible to the ground; Pizarro and his men rushed out from the surrounding buildings and set upon the astonished Incas. Of the Spaniards, only Pizarro himself was wounded when he seized Atahualpa, while the Incas were cut down in their hundreds.

Atahualpa was imprisoned and a ransom demanded: a roomful of gold and silver weighing 24 tons was amassed, but the Inca was not freed. He was held for nine months, during which time he learned Spanish and mastered the arts of writing, chess, and cards. His authority was never questioned: female attendants dressed him in robes of vampire-bat fur, fed him, and ceremoniously burned everything he used. The Spaniards melted down the finely wrought treasures, and accused Atahualpa of treason. Curiously, Pizarro baptized him “Fransisco,” and then garroted him with an iron collar.

Lament for Atahualpa

An elegiac lament was composed by the Incas upon the death of their leader Atahualpa: “Hail is falling/Lightning strikes/The sun is sinking/It has become forever night.” Atahualpa is still considered by many people to have been the first great Ecuadorian. Curiously, Pizarro baptized him with his own Christian name, Francisco, before garroting him with an iron collar.

There are indigenous people today, in the Saraguro region, who are said to wear their habitual somber black and indigo ponchos and dresses because they are still in mourning for the death of Atahualpa, nearly 500 years ago.

Francisco Pizarro.

Alamy

Two worlds collide

To the Incas, the Spanish conquest was an apocalyptic reversal of the natural order. In the eyes of a 16th-century native chronicler, Waman Puma, these strangers were “all enshrouded from head to foot, with their faces completely covered in wool… men who never sleep.”

The Incas had no monetary system and no concept of private wealth: they believed the only possible explanation for the Spaniards’ craving for gold was that they either ate precious metals, or suffered from a disease that could be cured only by gold. Their horses were “beasts who wear sandals of silver.”

Conversely, the conquerors perceived the native peoples as semi-naked barbarians who worshiped false gods and were good for nothing; Cieza de León’s positive remarks only illustrate his unusual fair-mindedness.

While Pizarro continued southward toward Cuzco, his lieutenant, Sebastián de Benalcázar, was dispatched to Piura to ship the Inca booty to Panama. But rumors of these treasures had traveled north, and Pedro de Alvarado, another Spaniard in search of riches, set out from Guatemala to conquer Quitu. With 500 men and 120 horses, he landed at Manta in early 1534, and during an epic trek slaughtered all the coastal natives who crossed his path.

Hearing of this, Benalcázar quickly mounted his own expedition to capture Quitu. Approaching Riobamba in May, he encountered a massive Quiteño army under the Inca general Quisquis. Fifty thousand soldiers, the largest Inca force ever assembled, were deployed, hopelessly outnumbering the Spaniards. But the soldiers, owing no loyalty to the Incas, mutinied and dispersed, and the best opportunity to defeat the Spanish was lost. Alvarado was paid a handsome sum by Pizarro to abandon his Ecuadorian excursion and return quietly to Guatemala.

Benalcázar marched northward with thousands of Cañaris and Puruháes in his ranks, for both tribes sought revenge on the brutal Incas. Arriving in Quitu in December, 1534, he found the city in ruins; Rumiñahui, the Inca general, had destroyed and evacuated it rather than lose it intact. Atop Cara and Inca rubble, with a mere 206 inhabitants, the Villa de San Francisco de Quito was founded on December 6, and Guayaquil the following year. Rumiñahui launched a counter-attack a month later, but was captured, tortured, and executed.

By 1549, the conquest was complete: a mere 2,000 Spaniards had subjugated an estimated 500,000 native Ecuadorians. The number of casualties is impossible to ascertain, but tens of thousands died in this 15-year period, through starvation, disease, and suicide, as well as in battle.

The Spanish yoke

Having conquered the native peoples, the conquistadors fought each other for the prizes: not until 1554 did the Spanish crown finally subdue them. In 1539, Pizarro appointed his brother Gonzalo governor of Quito, but when the first viceroy to Peru passed through shortly there-after, he found the colonists in revolt. Gonzalo fought off the viceroy’s forces in 1546, only to be deposed and executed by another official army two years later. During Gonzalo’s governorship, an expedition was mounted to explore the lands east of Quito. The undertaking was a disaster , but under the renegade leadership of Francisco de Orellana, the first transcontinental journey by Europeans was made in 1541.

The construction of San Francisco in Quito.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

When Cortés cried, “I don’t want land; give me gold!” he spoke for all conquistadors. But the immediately available treasures were soon exhausted. The land and its inhabitants were divided among the conquistadors, and the first settlers soon followed. Of the Quito region, in contrast to the damp, ghostly barrenness of Lima, Cieza de León wrote: “The country is very pleasant, and particularly resembles Spain in its pastures and climate.”

The Avenue of the Volcanoes, the strip of land 40 to 60km (25 to 40 miles) wide running the length of Ecuador between two towering rows of volcanoes, was ideal farmland. In addition, workshops were established to produce textiles, and slaves were brought from Africa to man the coastal cacao plantations. Ecuador escaped the grim excesses of mining that befell Peru and Bolivia, as the Spanish, to their disappointment, found few precious metals here.

As well as horses, pigs and cattle were introduced, and Ecuador nurtured the first crops of bananas and wheat in South America. The Spaniards also imported diseases such as smallpox, influenza, measles, and cholera. But with much of the highlands and all of the Oriente so inaccessible, Spanish settlement was relatively light, so geography saved the native peoples from extermination, if not from subjugation.

Colonial administration was based on the twin pillars of the Church and the encomienda system, where encomenderos (land-owners) were given tracts of land and the right to unpaid native labor, and in return were responsible for the religious conversion of their laborers. The laborers were obliged to bring tribute, in the form of animals, vegetables, and blankets, to their new masters, as they had to the Incas. It was a brutally efficient form of feudalism, whereby the Spanish crown not only pacified the conquistadors with a life of luxury, but also gained an empire at no risk or expense. For centuries, the main landowner was the Church, as dying encomenderos donated their estates, in the hope of gaining salvation. Pragmatically, indígenas accepted the new faith, embellishing it with their own beliefs and rituals. Days after Benalcázar founded Quito, the cornerstone of the first major place of Christian worship, the church of San Francisco, was laid. Franciscans were followed by Jesuits and Dominicans, each group of missionaries enriching themselves at the indígenas’ expense.

Methods of conversion could be brutal: children were separated from their families to receive the catechism; lapsing converts were imprisoned, flogged, and their heads were shaved. Some priests took native women as mistresses, and their children contributed to the number of mestizos, people of mixed Spanish-native blood. Quito – seat of a Viceregal Court or Audiencia from 1563 – grew into a religious and intellectual center during the 17th century as seminaries, libraries, and universities were established. Art, particularly painting and sculpture, flourished in Quito and was exported to other parts of the Spanish Empire.

Push for independence

In reaction to the Spaniards’ oppressive socio-economic actions there sprouted violent popular uprisings and nascent cries of “Liberty!” As early as 1592, the lower clergy supported merchants and workers in the Alcabalas Revolution, protesting against increased taxes on food and fabrics. The authorities put an end to the agitation by executing 24 conspirators and displaying their heads in iron cages.

During the 1700s, the ideas of the European Enlightenment crept slowly toward Quito University. The works of Voltaire, Leibnitz, Descartes, and Rousseau, and the revolutions in the United States and France, gave intellectual succor to colonial libertarians. The physician-journalist Eugenio Espejo, born in 1747 of an indigenous father and a mulatto (Afro-Hispanic) mother, emerged as the anti-imperialists’ leader.

Espejo was a fearless humanist. He published satirical, bitterly combative books on Spanish colonialism; and as founding editor of the liberal newspaper Primicias de la Cultura de Quito, was probably the first American journalist. He was repeatedly jailed, exiled to Bogotá for four years, and finally died, aged 48, in a Quito dungeon. From his cell, he wrote to the President of the Audiencia: “I have produced writings for the happiness of the country, as yet a barbarian one.”

Von Humboldt: The first travel writer

According to the German scientist, Ecuadorians sleep calmly under active volcanoes, live in poverty atop riches, and are cheered by sad music. This still rings true.

Simón Bolívar described Humboldt as “the true discoverer of America, because his work has produced more benefit to our people than all the conquistadors.” Praise indeed from the liberator of the Americas. But how did this wealthy Prussian mineralogist come to play such a vital role in the history of the continent?

Alexander von Humboldt was born in Berlin in 1769. As a young man he studied botany, chemistry, astronomy, and mineralogy, and traveled with Georg Forster, who had accompanied Captain James Cook on his second world voyage. At the age of 27 he received a legacy large enough to finance a scientific expedition, and made such an impression on Charles IV of Spain that he received special permission to travel to South America.

Humbolt’s expedition

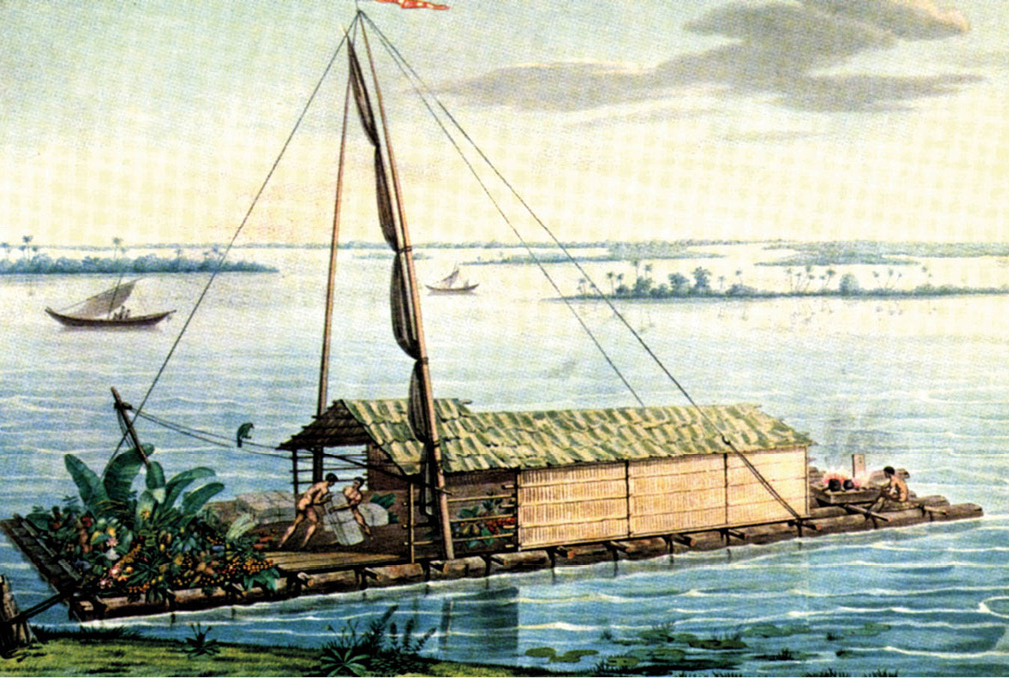

With his companion Aimé Bonpland, Humboldt set off for Caracas in November 1799. During their five-year expedition the two men covered some 9,600km (6,000 miles) on foot, horseback, and by canoe; suffered from malaria; and were reduced to a diet of ground cacao beans when damp and insects destroyed their supplies. Following the course of the Orinoco and Casiquiare rivers, they established that the Casiquiare channel linked the Orinoco and the Amazon. In 1802 they reached Quito, where Humboldt climbed Chimborazo, failing to attain the summit but setting a world record (unbroken for 30 years) by reaching almost 6,000 meters (19,500ft). He coined the name “Avenue of the Volcanoes” and, after suffering from altitude sickness, was the first to realize its connection with a lack of oxygen. Between ascents he studied the role of eruptive forces in the development of the earth’s crust, establishing that Latin America was not, as had been believed, a geologically young country.

A man of many interests

While in Ecuador, Humboldt began assembling notes for his Essays on the Geography of Plants, pioneering investigations into the relationship between a region’s geography and its flora and fauna. He claimed another first by listing many of the indigenous, pre-conquest species; and he was responsible for the birth of the guano industry, after he sent samples of the substance back to Europe for analysis.

Humboldt’s contributions seem endless: off the west coast he studied the oceanic current, which was named after him; his work on isotherms and isobars laid the foundation for the science of climatology; he invented the term “magnetic storms,” and as a result of his interest the Royal Society in London promoted the establishment of observatories, which led to the correlation of such storms with sunspot activity.

He was also deeply interested in social and economic issues and was adamantly opposed to slavery, which he considered “the greatest evil that afflicts human nature.” Goethe, a close friend, found him “exceedingly interesting and stimulating,” a man who “overwhelms one with intellectual treasure”; while Charles Darwin had been inspired by Humboldt’s earlier journey to Tenerife, in the Canary Islands, and his description of the volcanic Pico de Teide and the dragon tree. Darwin respectfully described him as “the parent of a grand progeny of scientific travellers.”

A color print after a drawing by Alexander von Humboldt from his expedition rafting on Guayaquil River.

Mary Evans Picture Library