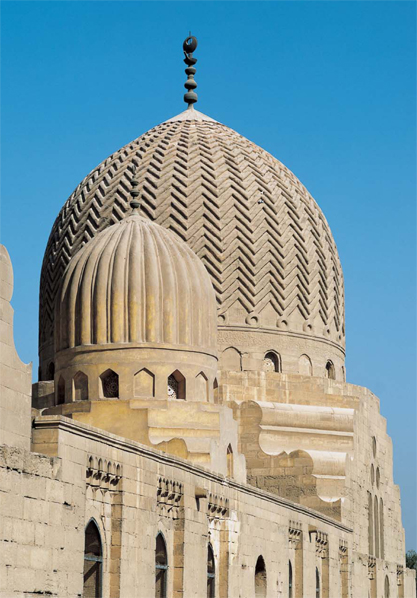

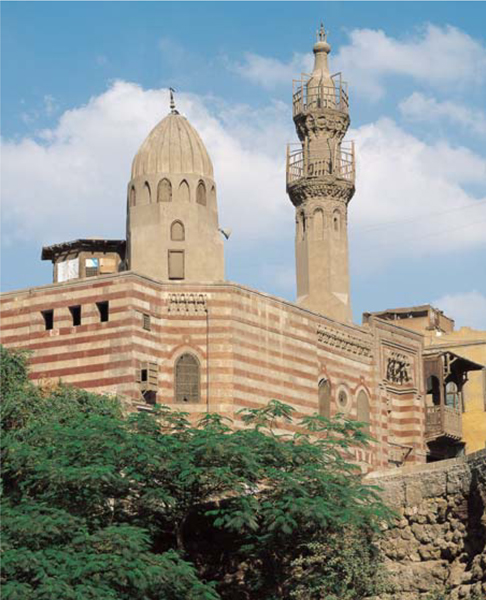

Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, general view, Cairo

Salah El-Bahnasi, Mohamed Hossam El-Din, Gamal Gad El-Rab, Tarek Torky

I.1.b The Citadel Towers: al-Ramla and al-Haddad

I.1.c Tower of Sultan Baybars al-Bunduqdari

I.1.d Ruins of al-Ablaq Palace

I.1.e Mosque of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad

I.1.f Madrasa of Qanibay Amir Akhur

I.1.g Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan

I.1.h Madrasa of Gawhar al-Lala

I.1.i Entrance of Manjak al-Silahdar Palace

I.1.j Entrance of Yashbak min Mahdi Palace

Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, general view, Cairo

The Citadel, view from the North Cemetery, Cairo (D. Roberts, 1996, courtesy of the American University of Cairo).

When Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi had his Citadel built, his desire was for it to be both a defensive fortress and the seat of the Sultanate. His initial lack of trust in Cairenes led him to have the Citadel located at a distance from the city, the construction of which followed the fortress model of the Crusades. Architectural innovations were introduced, however, mainly ideas gathered during Salah al-Din al-Ayyub’s time spent in Aleppo and on campaigns carried out in Syria and Palestine against the Crusaders. Such elements are evidenced by the bent passageway entrances rendering access from the outside difficult while aiding defence from the inside and by the machicolations, or projecting galleries, from which to observe and attack the enemy. The Citadel was sited in an ideal defensive position, overlooking the city of Cairo to the north and Fustat to the south, the desert and rocky hills bordering to the north and east.

The North Wall of the Citadel (military section)

Salah al-Din entrusted the construction of the Citadel to his Minister Baha’ al-Din Qaraqush al-Asadi who began with the north curtain wall which he built along an irregular line for defensive purposes. The main gate, al-Bab al-Mudarrag (the “Staircase Gate”) is located in the west wall crowned by a foundation plaque, which dates the gate to the year 579/1183. It was later restored in 709/1309 by the Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun. Several semicircular towers are placed along the length of the walls, of which al-Ramla and al-Haddad towers, located on the eastern edge, are particularly noteworthy (I.1.b). This section, which was reserved for the armies, contained buildings used as Mamluk lodgings, none of which have survived to our day.

In the year 901/1496 the German knight Arnold Von Haref arrived in Cairo on his way to Jerusalem, seeking permission from the Sultan of Egypt, al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qaytbay to travel to Palestine and Syria. The Sultan took interest in the man and invited him to an audience at the Citadel. The book that Arnold Von Haref wrote on his journey provides us with records of palaces, houses and a Mamluk school, where 500 young men were trained in the art of horse-riding, while also learning to read and write.

Next to Bab al-Mudarrag we find three marble plaques bearing details of successive restorations carried out by different sultans. Firstly Sultan Jaqmaq’s renovations on the gate in 842/1438; the second was carried out by Sultan Qaytbay in 872/1468 and the third by Sultan al-‘Adil Tumanbay in 922/1516, the latter two being aimed at strengthening the walls of the Citadel.

The South Wall of the Citadel (residential section)

There is evidence that work commenced in this area with the well Qaraqush dug at the same time that the northern walls were being built. The well, guaranteeing the supply of water to the garrison, is accessed by a descending spiral staircase and is divided into two parts by a water wheel of earthenware vessels. The wheel raised water to a tank located half-way up the well shaft and from there, water was brought to the surface by other wheels.

Later, Sultan al-Kamil Ibn al-‘Adil al-Ayyubi would have the royal palaces built and it was then that he had the seat of power established in the Citadel to which he brought his family and government. Henceforth, the Citadel remained the seat of government and residence of governors of Egypt until 1291/1874 in the era of the Khedive Isma‘il.

With the arrival of the Mamluk Sultans, earlier palaces built by al-Kamil were reconstructed and converted into three royal residences known as the Palaces of al-Guwaniyya near the al-Ablaq Palace (I.1.d). Furthermore, Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad commissioned a great iwan for the council of the Sultanate to meet. The southern stretch of wall was surrounded by another, the ruins of which still survive today in the al-Siba’ tower (I.1.c) dating back to the reign of Sultan Baybars I al-Bunduqdari.

These walls separated the residential area from the Sultan’s stables. Among those who most influenced the building of the Citadel are Sultan Baybars and the Qalawun family, who definitively established the seat of the Mamluk Sultanate there. Unlike the events marking the first half of the Citadel’s history, when the Ayyubid governors made every attempt to isolate it from their people, the two Mamluk Sultans were concerned with opening up the Citadel to its people.

Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, entrance, Cairo (D. Roberts, 1996, courtesy of the American University of Cairo).

In the stables’ area we find the mosque known as Ahmad Katkhuda al-’Azab which goes back to the time of the Burgui Mamluks. It was built in the year 801/1399, during the reign of Farag Ibn Barquq.

Mamluk Monuments outside the Citadel

During the times of the Mamluk sultans, the wall over the Citadel Square (al-Rumayla) was embellished with several dazzling palaces, reflecting the grandeur and opulence of the Sultanate. Citadel Square is considered one of the oldest squares in Cairo. During Ayyubid rule and from the beginning of the 6th/12th century it became the city’s centre of gravity. Al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun planned the urban layout and had palm and other trees planted; around it he was to have a stone wall built, such that the square was transformed into a vast space stretching well below the walls of the Citadel, from the gate of the stables to the cemetery (nowadays Sayyida ‘A’isha).

During the Mamluk era building work continued within the Citadel walls around the square of the same name and with the houses of Sultan Baybars’ amirs and successors. Among the most noted constructions are the Palaces of Yashbak min Mahdi (I.1.j), Manjak al-Silahdar (I.1.i) and Alin Aq al-Husami. The horse (al-Khuyul) and armourers (al-Silah) suqs, thought to have reached perfection as model specialist suqs, were also transferred to this area, in the vicinity of the Mosque of Sultan Hassan.

Around the Citadel, numerous religious buildings were erected, among them the Madrasas of Sultan Hassan (I.1.g), Gawhar al-Lala (I.1.h) and Qanibay al-Rammah (I.1.f).

M. H. D. and T. T.

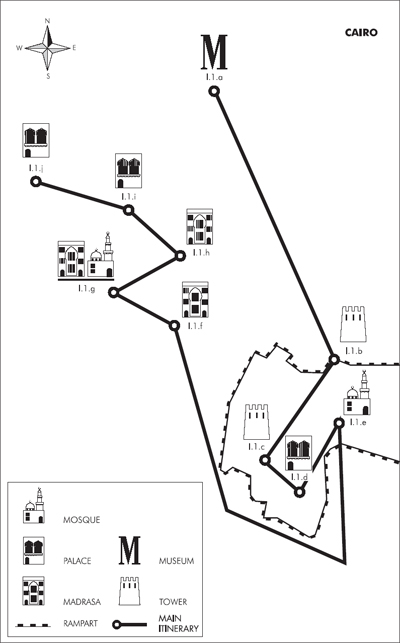

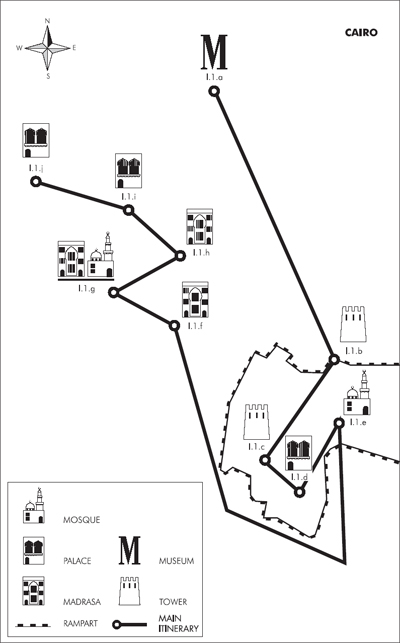

I.1.a Museum of Islamic Art

The museum is located near Bab al-Khalq, opposite the Cairo Directorate of Security.

Opening times: daily from 09.00-16.00 closed Fridays 11.30-12.30 in winter and 13.00-14.00 in summer. There is an entrance fee.

In 1880, the Commission for the Conservation of Arab Monuments was founded with the aim of creating a complete inventory of works of art in the different Islamic houses, palaces and mosques. Of these pieces, 110 were transferred to the Arab Archaeological Museum, a building in the courtyard of the Fatimid Mosque, al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, next to the north walls of the city. The collection continued to expand acquiring artefacts from the Commission and the first catalogue of the collection was published in 1895. Given the limited space of the site, another larger museum was built in Bab al-Khalq, next to the Egyptian National Library in 1903, to which the Arab Archaeological Museum transferred its collection. The building, designed along traditional Islamic lines in keeping with the works on display, held onto its name. While the collection belonged to the artistic legacy of the Arab countries, it also housed a variety of art collections from non-Arab Islamic countries, such as Turkey, Iran and India. Thus, it was decided in 1953 that the name should be changed to the Museum of Islamic Art.

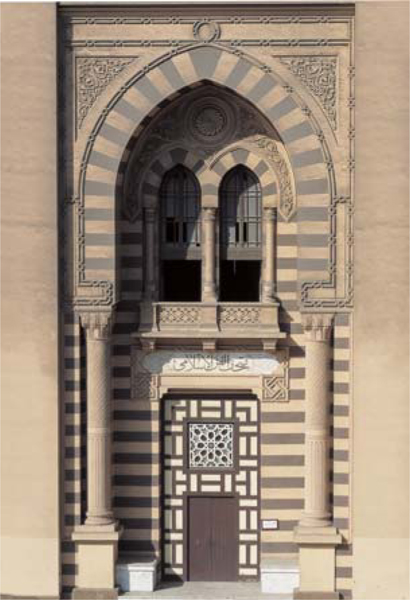

Museum of Islamic Art, main façade, Cairo.

The greatest collection in the world of Islamic archaeology, comprising some 100,000 pieces is found here. The works occupy 25 rooms on two floors and are displayed in chronological order from the Umayyad period through to the end of the Ottoman period. The pieces are classified according to the materials used in their manufacture and their country of origin. Mamluk art occupies a special place among the acquisitions. The collection includes ceramic vessels (the style imitates celadon porcelain from China and Sultanabad ceramics from Iran), and a collection of enamelled terracotta pieces, characterised by the inscriptions and arms of the Mamluk Amirs and Sultans. The collection of wooden articles testifies to the variety of techniques used in the decoration of this material, including carving, turning and inlay. Among the most important wooden articles is a screen from the Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, demonstrating the turned wood technique and a Qur’an case, decorated with ebony and ivory, from the Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha’ban.

Museum of Islamic Art, entrance, Cairo.

Among the Mamluk masterpieces in the museum is a collection of metal artefacts, a testimony to the degree of perfection attained in the period and to the skill with which artisans produced all manner of decoration in gold and silver inlay on bronze basins and bowls. Zayn al-’Abidin Katbugha’s candlestick, Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad’s kursi al-’asha’ (dining table) and Qaytbay’s candlestick are among the most representative examples of metalwork from the Mamluk period.

Wooden panel, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 11719), Cairo.

The technique of glass enamelling was to reach its greatest expression in both precision and perfection during this period, as evidenced by this collection of 60 glass lamps from the Mamluk era, a representative sample of some 300 lamps in different museums of the world. Most outstanding are the lamps from the Madrasa of al-Nahhasin belonging to Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun. The 19 lamps bear the name and titles of Sultan Hassan, son of al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun, and those of Sultan al-Ashraf Sha’ban.

Ceramic bowl, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 5707), Cairo.

The Museum’s collection of textiles from the Mamluk era highlights the characteristics of this art form. On a piece of silk bearing the name of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun, depicting a family of leopards, the fineness of the cloth and its exquisite decoration may be fully appreciated. The carefully hand-crafted rugs of Mamluk artisans were highly prized among Europeans. Proof of their widespread popularity in Europe is found in their representation in the work of other artists during the Renaissance, in particular in Italy, and above all in the paintings of Carpaccio.

Among other valuable works of art we find examples of manuscripts, which help us to understand book-production techniques of the period, including calligraphy, illumination, gilding and binding. These manuscripts, and in particular the work Al‘ab al-Furusiyya, show how the Egyptian school of illustration held onto characteristics from the Arabian school, which by then had already disappeared in Iran and Iraq following Mongol invasion.

Among the most important acquisitions of the Museum of Islamic Art is its coin collection, comprising gold Dinars, silver Dirhams and bronze coins, all rich in inscriptions.

S. B.

Decorated wooden panel

(Mamluk room, reg. no. 11719, 8th/14th century)

This wooden panel is decorated with small interlocking pieces forming geometric shapes. The centre bears a star-shaped motif, inlaid with ebony and ivory.

Bronze candlestick, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 4463), Cairo.

Ceramic bowl (Mamluk room, reg. No. 5707, 8th/14th century)

Under the glazed enamel, this large ceramic bowl is decorated with a gazelle raising her head as if to eat the leaves from trees. The drawing is outlined in white on a blue background, bearing Chinese-style decoration of branches covered in leaves and lotus flowers. The drawings are surrounded by a circular border, closely resembling inscription in naskhi script, of exquisitely slender letters.

Brass candlestick (Mamluk room, reg. no. 4463, 7th/13th century)

Marble plaque, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 278), Cairo.

The brass candlestick with silver inlay (height 14 cm. and 8 cm. diameter at the top) has a cylindrical base, that narrows to form a cone-shaped top with a flat ring and protruding edges. The broad band around the base shows figures of dancers, which are at the same time the body of the letters of a naskhi inscription; it reads “glory and eternal life triumph over the enemy”. The edges of the upper ring also bear naskhi inscriptions on a background of carefully spaced small leaves. The inscription reads: “the victorious, the glorious, Zayn al-’Abidin Katbugha, painted the tashtakhana (crockery store) of this venerated place”.

Decorated marble plaque (Mamluk room, reg. no. 278, 8th/14th century)

The centre of this decorated marble plaque bears a large oval medallion. The bas-relief decoration presents a background of hands reaching out to branches with flowers and birds. The plaque comes from the Mosque of Amir Sarghatmish built in Cairo in the year 757/1356 (IV.1.h).

Glass lamp

(Glass room, reg. no. 270, 8th/14th century)

This glass lamp bearing red and blue enamel is decorated with inscriptions that bear the name of the Sultan Qaytbay. It no longer has its base, but the neck bears a band with flower decorations in Renaissance style, evidence that it was made in Europe, probably in Venice.

Glass lamp

(Glass room, reg. no. 33, 9th/15th century)

This glass lamp decorated with red and blue enamel and gold measures 33 cm. in height and the neck, 25 cm. in diameter. It is decorated with a symmetrical lotus flower and peony design common in Chinese art, on a background of smaller sixpetalled flowers and small plant leaves. The drawings have a red enamel outline on a background of blue enamel. The lamp, with handles, comes from the Mosque of Sultan Hassan (I.1.g).

Glass lamp, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 33), Cairo.

Glass lamp, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 270, Cairo.

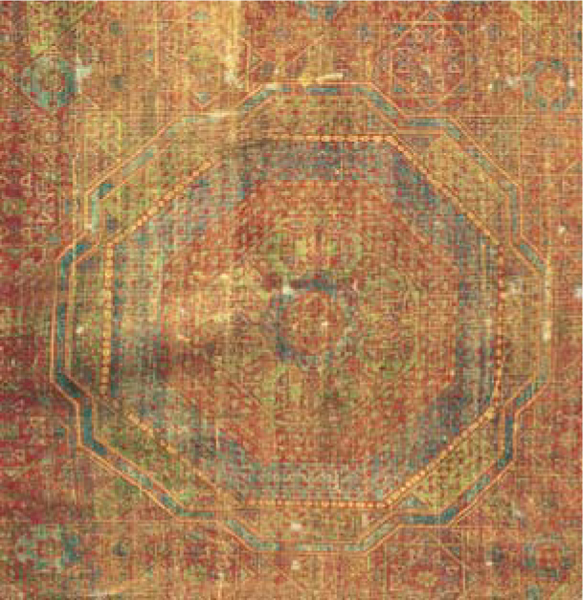

Fragment of carpet

(Carpet room, reg. no. 1651)

This fragment of Mamluk-style rug bears geometric designs and measures 20.9 m. in length and 1.94 m. in width. A large octagonal medallion can be seen in the centre with eight pointed stars in red, violet, sky-blue and white.

T. T.

Fragment of carpet, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 1651), Cairo.

I.1.b The Citadel Towers: al-Ramla and al-Haddad

The Citadel can be reached from Salah Salim Avenue on the road to Mount al-Muqattam. The entrance is through the present-day Main Gate in front of which there is a large car park for coaches and cars. Al-Ramla and al-Haddad towers are located in the (military section) Citadel on its eastern edge.

Within this area of the walls and towers there is an open-air amphitheatre (Mahka al-Qal’a) officially opened in 1994 where exhibitions, artistic events, concerts and summer festivals are held. Near the amphitheatre there are public toilets as well as those inside the Citadel near the cafeteria.

Opening times: from 08.00 to sunset. There is an entrance fee.

Towers of al-Ramla and al-Haddad, Cairo.

Since their construction, the Citadel towers (burg in the singular) were used as barracks for soldiers. The towers were closely associated with the Circassian Mamluks, from the reign of Sultan Qalawun onwards, who had his soldiers lodged in them on their arrival in Egypt, hence the nickname they acquired “Burgui Mamluks”.

Among the towers located on the northern stretch of wall we find al-Ramla and al-Haddad on its eastern end. These circular towers of a height of 20.8 m. have three floors including the upper flat roof. The walls are built of rusticated blocks with loopholes at intervals. These openings were widened during the time of Sultan al-‘Adil, brother of Salah al-Din and can be reached from a platform covered by a vault.

The upper open-air floor can be reached by an inner staircase. Openings on the parapet at intervals allowed surveillance and control tasks to be carried out. Al-Haddad tower differs from al-Ramla tower and others in that it has four machicolations supported on brackets and its middle floor is octagonal similar to a durqa’a.

G. G. R.

From the top of the towers the visitor has a splendid panoramic view of Mount al-Muqattam, which includes al-Guyushi Mosque, Salah Salim Avenue, ruins of the Citadel towers and its surrounding wall.

I.1.c Tower of Sultan Baybars al-Bunduqdari

This tower is located in the residential sector of the Citadel, where the north wall joins the west. The Police Museum (with a cafeteria) was built in 1983.

Tower of Sultan Baybars al-Bunduqdari (Burg al-Siba’), Arms of Sultan Baybars on the façade, Cairo.

Sultan Baybars al-Bunduqdari had the tower built on the intersection of the north and west walls of the southern Citadel wall, known as Burg al-Siba‘ (“Tower of Lions”) inside the Citadel. As such, historians have referred to it in their writings as the “Corner Tower”. It owes its true name, however, to the upper section of its façade, uncovered when construction of the Police Museum commenced. Figures of lions, the emblem of Sultan Baybars, were uncovered. A total of 100 lions were painted on its eastern wall and 12 on its north. Lions were also found on many other buildings of his; on the façades of the al-Ablaq Palace constructed in Marja, Damascus; on the bridges built in Cairo (in the present day al-Sayyida Zaynab Quarter) hence the name of the “al-Siba‘ Bridges”, which are now extinct.

S. B.

From here you have a panoramic view of both Old Cairo and Modern Cairo. On looking over the Citadel Square, major Cairene monuments are in view; among them the Mosques of Sultan Hassan and al-Rifa‘i, the Madrasas of Qanibay Amir Akhur and Gawhar al-Lala, the Mosques of al-Mahmudiyya and Ahmad Ibn Tulun and hundreds of minarets scattered throughout the city affording a splendid and unforgettable view.

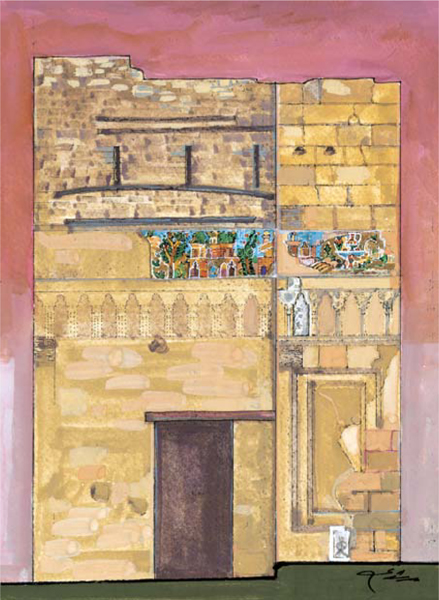

I.1.d Ruins of al-Ablaq Palace

The ruins of the al-Ablaq Palace are located in the vicinity of Sultan Baybars al-Bunduqdari tower, below what is today ground level.

Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun was to commission his palace, called al-Ablaq Palace on the west side of the southern enclosure of the Citadel of Salah al-Din in 713/1313. On the basis of archaeological finds in the area, the palace is believed to have stretched from the outer wall of the Citadel to the entrance hall of al-Gawhara Palace. The palace was reserved for the Sultan to hold his daily audiences and above all, for the administration of State affairs, though special occasions were also celebrated there. Its name derives from the building technique known as al-ablaq, consisting of alternating courses of black-and-white stone (the white stone over time has yellowed).

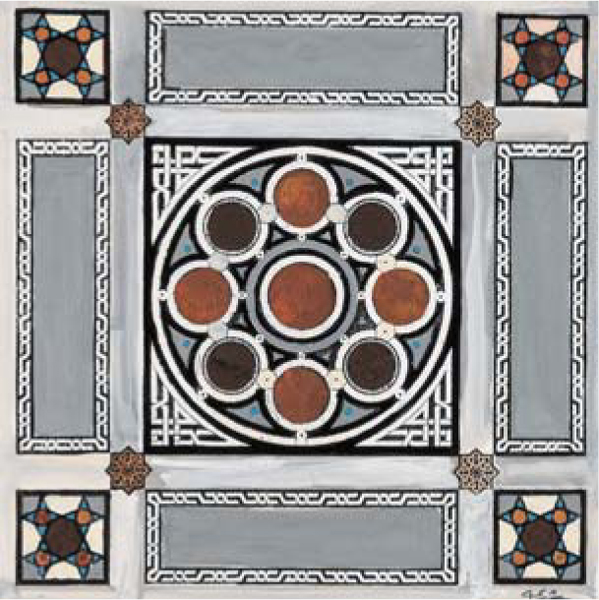

Ruins of al-Ablaq Palace in the Citadel, Cairo (painting by Mohammed Rushdy).

From archaeological finds we know that the floor plan comprised two iwans and a durqa‘a. This layout closely follows that of other palaces of the period such as the Alin Aq al-Husami and Bashtak Palaces (see Itinerary II). On evidence from other similar structures we can assume this palace had two iwans and a durqa‘a, its centre covered by a dome. From the northern iwan, larger than the southern iwan, the Sultan could look out over the imperial stables, the horse bazaar (al-Khuyul) in the Citadel Square and over the city of Cairo, and from the River Nile to Giza. Access to the remaining palace rooms and to the complex of buildings, such as the great iwan and the al-Guwaniyya Palaces, was gained through the southern iwan, built by al-Nasir Muhammad in the Citadel. The palace was subsequently abandoned. It was later turned into the Kiswa factory for the Ka’ba in Ottoman times, and finally Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (1220/1805-1265/1849) was to have his mosque built over the hypostyle hall of the palace. Alterations have left the building stripped of its original wealth and magnificence. Nevertheless, the works of the Khitat written by the historian al-Maqrizi bear testimony to its decorative features. He mentions floors and walls covered with marble and ceilings of gold and lapis lazuli. On the lower part of one of the durqa‘a walls there are still vestiges of marble, and on the upper part of the same section a piece of gilt marble mosaic can be seen indicating that a panel of the same material once covered the entire wall. The mosaic contains floral and geometric designs very similar to those panels still visible today in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus.

S. B.

Mosque of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, dome and minaret, Cairo.

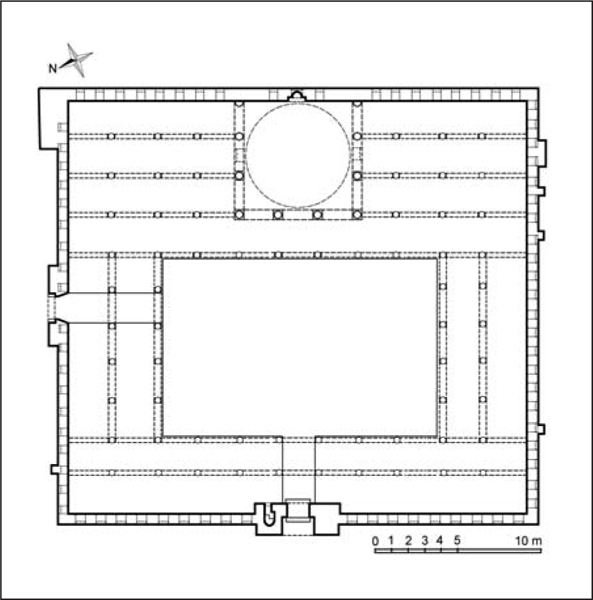

I.1.e Mosque of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad

This mosque is situated within the grounds of the Citadel, opposite Bab al-Qulla and is reached on leaving the Police Museum area.

The third reign of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad from 709/1310 to 740/1340 was marked by the unprecedented development that took place in the city of Cairo, which saw an increase in the number of monumental buildings there. The Sultan began a vast building programme in the Citadel. The enormous domes of his palace (al-Ablaq Palace) and mosque (measuring 8 m. and 15 m. in diameter respectively) were to dominate the skyline until the 19th century when Muhammad ‘Ali (1820-1857) had his mosque built in the grounds.

Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad was to build his mosque in 718/1318 in the southern area of the Citadel. In 735/1335 it was extended to accommodate nearly 5,000 faithful, and remained the congregational mosque for the inhabitants of the Citadel and its vicinity throughout Mamluk rule and beyond into the Ottoman period.

The mosque appears suspended as the supporting arches of the lower floor can be seen. Its rectangular plan (63 m. x 57 m.) centres on a courtyard surrounded by four porticoes or arcades of two rows of arches in height. The side and rear arcades are two aisles deep, while the largest arcade is that of the qibla sanctuary comprising four aisles. The horseshoe arches are supported on marble and granite columns taken from different buildings of earlier periods (Ptolemaic, Roman and Coptic). In each of the two nearest arcades to the qibla, two columns have been left out directly in front of the mihrab in order to open up a square space there. A dome rises above the space originally made of wood, but it has on several occasions since its construction been restored and more recently rebuilt. The rest of the ceiling over the prayer hall is wooden with a coffered ceiling of small octagons. The mihrab in the qibla wall and the two niches on either side equal in height to the mihrab are decorated in marble and mother of pearl.

Mosque of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, dome and minaret, Cairo.

The mosque has two entrances and two minarets. The stone minarets, one in the southeast corner over the residential quarter, and the other over the northwest entrance towards the military sector, are the most outstanding feature of the mosque. The southeast minaret has a rectangular base, a cylindrical middle section and is crowned with a gawsaq (colonnaded pavilion). The second minaret decorated in high relief has cylindrical lower and middle sections with carved horizontal zigzags and vertical zigzags, respectively. The upper section displays a deep-fluted carved design. Both minarets are crowned with fluted bulbiform domes, the finials decorated with green glazed tiles similar to the main dome, and bearing an inscription in white on a blue background. This unusual decorative style formed part of the restoration work carried out on the mosque in 736/1335, during which the walls were raised, the ceiling rebuilt, and the upper sections of the minarets decorated with brick and glazed tile.

Faience, or glazed tile, and brick techniques along with bulbiform domes are clearly not a tradition of Cairene origins. Renowned for her prosperity, Cairo attracted many foreign artisans to the city during the reign of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad. With Mamluk-Mongol relations growing closer in the 720s/1320s Persian techniques and motifs became more widespread. Al-Maqrizi recounts how a master craftsman from Tabriz (a city in northwest Iran) took part in the reconditioning of the mosque and how the minarets were built in the same style as those of ‘Ali Shah Mosque in Tabriz. The main entrance portal to the mosque on the north west façade displays a trilobed arch. The second entrance is on the north east side, opposite Bab al-Qulla where the north and south Citadel walls join. Like the main entrance, this portal has a characteristic tri-lobed arch. A third entrance in the south east wall is once thought to have existed in the second qibla aisle, the private access of the Sultan from the area reserved for the harem (al-harim); nowadays the door is blocked.

Mosque of Sultanal-Nasir Muhammad, decorations of the dome over the mihrab, Cairo.

The upper row of arcades overlooking the courtyard shows openings resembling those in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus. Around the courtyard we find cresting, the corners topped with small incense-burner decorations. While this mosque awoke great interest during the Mamluk reign, in particular in Sultan Qaytbay who was to have the minbar restored in coloured marble, the mosque was abandoned during the period of the Ottoman Empire, and the dome and minbar fell into ruin. During the British occupation of Cairo, the mosque was used as a military store and prison. In 1947, the Commission for the Conservation of Arab Monuments was to take charge of its restoration, rebuilding its dome and adding a wooden minbar, bearing the name of King Faruq I.

S. B.

I.1.f Madrasa of Qanibay Amir Akhur

The Madrasa of Qanibay Amir Akhur is located in Salah al-Din Square opposite Bab al-Silsila (nowadays Bab al-‘Azab) leading to the Sultan’s stables.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer). The madrasa is currently being restored and visitors are not allowed inside.

Amir Qanibay, amir akhur (in charge of the Sultan’s stables), ordered this madrasa to be built in the time of Sultan al-Ghuri. This information is shown on the entrance and on one of the walls of the mausoleum. The madrasa was located near both the horse bazaar (al-Khuyul; in its singular al-Khayl) and the stables on the lower enclosure of the Citadel. The problem of the irregular, stepped ground was ingeniously resolved by building its different rooms on various levels. The sabil and kuttab were located on the lower-ground floor while the mosque and madrasa, which are reached by a staircase, were built above the storerooms. The madrasa is located next to the southwest wall. The entrance is a tri-lobed arch, above which there is another arch, the voussoirs of which take the shape of interlocking trefoil leaves. A hollow space has been left between the lintel and the arch. The minaret is located to the left of the entrance and has square lower and middle sections, both of which are crowned with balconies supported on stone muqarnas brackets. The upper section comprises two tall rectangular-based bodies, both crowned with a muqarnas cornice and a bulbiform dome. The minaret has two finials or “heads”, rather than the usual one, thus appearing to be a double minaret. It is the oldest of its kind in Cairo followed by the minarets of the al-Ghuri and al-Azhar Mosques.

The madrasa comprises an open durqa’a, surrounded by two iwans and two sadlas (small iwans). The sanctuary occupies the largest iwan, containing a stone mihrab and a small wooden minbar and is covered by a sail vault, while the iwan on the opposite side has a cross vault and two sadlas pointed barrel vaults.

The mausoleum is reached through a door in the southeast corner of the durqa’a. The tomb is square in shape with a dome resting on pendentives decorated with muqarnas. The sides of the octagonal drum under the dome have lamps recessed in the walls.

Madrasa of Qanibay Amir Akhur, main façade, Cairo.

The wealth of innovative architectural and decorative elements in the madrasa makes it one of the finest examples of Mamluk art. These features can be seen on both the façade, the floral decoration of the dome and the double-topped minaret, and on the inside, in the variation of its iwan and sadla ceilings and in the fascinating decoration on the walls.

The Commission for the Conservation of Arab Monuments restored the sabil, kuttab and minaret to their original style in 1939.

S. B.

I.1.g Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan

The Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan are on Citadel Square opposite the Mosque of Qanibay al-Sayfi. Opposite the mosque and madrasa is al-Rifa‘i Mosque, built at the beginning of the 20th century, where Khedive Isma‘il and King Fu’ad are buried along with, more recently, the Shah of Iran. The pedestrian walkway lined on either side by the buildings, opens into a garden with a café for those who wish to relax and enjoy the atmosphere of the place.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer).

Madrasa of Qanibay Amir Akhur, main façade, Cairo.

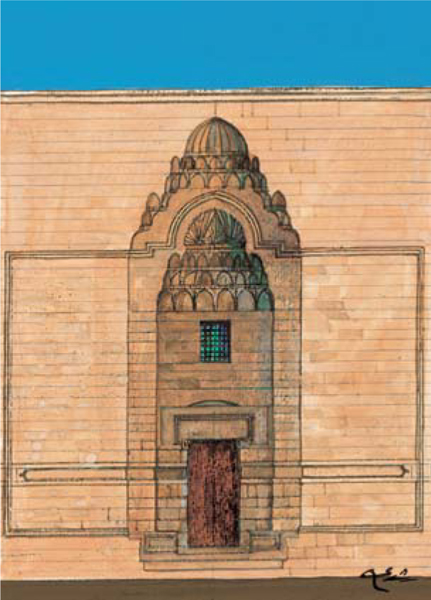

In 757/1356 Sultan Hassan Ibn al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun ordered the demolition of the palaces of Amirs Yalbugha al-Yahyawi and al-Tunbugha al-Maridani. They were located on the site of the horse bazaar (al-Khuyul) in the Citadel Square, and in their place, he had an architectural complex built. One of the main features of the buildings are their extensive façades on a slight up-hill slope crowned by muqarnas cornices, with tall shallow recesses regularly spaced along their length. Such positioning cleverly married the need for surveillance over the city with its facing Mecca, while also facing the direction followed by the Sultan’s procession in that period. It allowed anyone approaching the building from the Armourer’s bazaar (suq al-Silah) and in the direction of the Citadel to contemplate its vast façade in all its detail but not anyone approaching from the opposite direction.

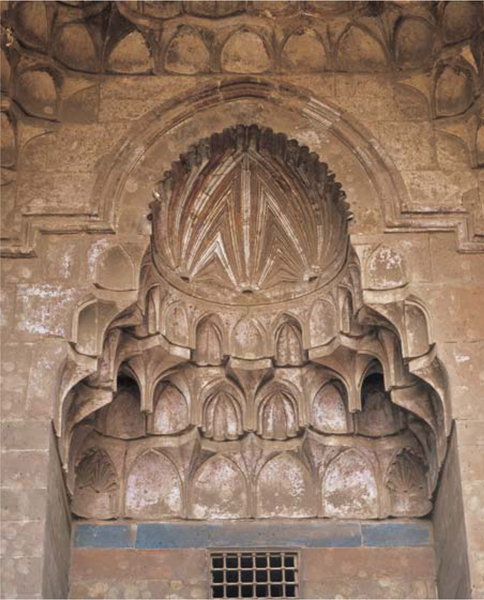

Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, decoration on the ceiling of the entrance derka, Cairo.

The Sultan Hassan Complex, combining a mosque and a madrasa, as was usual in the times of the Mamluk sultans, represents the apogee of several architectural achievements from the earlier Bahri era. Its proportions and positioning, however, render it exceptional, and as such, it has been chosen here to represent the masterpiece of Cairene Mamluk architecture.

With its lofty portal (36.7 m. high) and majestic semi-dome stalactite vault, the main entrance is the most lavish of Mamluk portals. From here access is gained to the cruciform-domed entrance hall that leads to the service area on one side and to the centre of the building along a double-bending passageway on the other. The floor area of this monumental complex, some 8,000 sq. m., is comprised two main bodies at angles to one another; the service wing with the main entrance being placed at an angle to the building housing the mosque, madrasa and mausoleum.

The complex contains lodgings for both teachers and students, and for employees of the madrasa. There were also rooms reserved for doctors, a library, baths, kitchens and the sabil with the kuttab above. The latter two are located on the side of the Armourer’s (al-Silah) bazaar, into which the original minaret to the right of the main entrance once fell killing every single person in the square at the time. The complex was originally designed to have four minarets; two, however, on either side of the portal were never built, the other two, restored in the 20th century, can be seen on either side of the qubba on the south east wall.

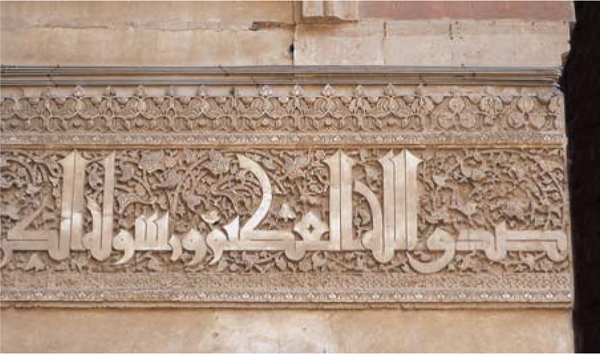

The mosque courtyard is paved with marble, in the centre of which an octagonal ritual ablutions fountain stands covered by a wooden dome supported on eight marble pillars. The courtyard is surrounded by four iwans. The largest is that of the qibla, in the centre of which we find the mihrab decorated in marble of three different colours, with gilt inscriptions. Beside the mihrab is the minbar, also in marble though undecorated. Its wooden door is faced in brass with gold and silver inlay. In front of the mihrab is the splendid marble dikkat al-muballigh, (recitation platform) from where the prayers of the day were repeated for all the faithful present to hear. The doors on either side of the mihrab lead to the mausoleum qubba. The positioning of the mausoleum behind the iwan meant that three of its sides were exterior walls gaining maximum visibility from the Citadel, the seat of Mamluk power.

An enormous vault the arch of which is said to be the largest ever built over an iwan in Egypt covers the sanctuary. Around the wall of the iwan a stucco band bears an inscription of Qur’anic verses, carved in Kufic script on a foliate background.

The remaining three iwans are smaller also covered by vaults. The doors flanking the north and south iwans lead to each of the four madrasas destined to be the venues for the teaching of each of the four legal rites (Shafi’i, Maliki, Hanafi and Hanbali). The largest of the four is the Hanafi Madrasa in which the name of the surveyor Muhammad Ibn Bilik al-Muhsini appears, who oversaw the building work. Each madrasa is centred on an open courtyard with a fountain for ritual ablutions, surrounded by four iwans. Adjoining are the students’ cells rising up to six floors in height.

In the centre of the square mausoleum hall, whose outer wall overlooks Salah al-Din or Citadel Square, is a wooden screen surrounding the raised marble tomb, which was initially prepared for the burial of Sultan Hassan. Here, however, it was his son al-Shihab Ahmad who was buried, as on the Sultan’s assassination his body was never recovered.

Masque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, decorative detail in the wall of the derka, Cairo.

Nowadays, the large stone dome over the mausoleum is the result of 17th-century restoration work following a fire that destroyed the original dome. The wooden pendentives with their carved muqarnas, luxuriously decorated in coloured paint and gold, originally supported the wooden dome. The mausoleum, with its beautiful mihrab, contains a Qur’an lectern said to be the oldest one known to Egypt. It also houses the largest mausoleum dome in the country, measuring 21 m. across and 30 m. in height. In addition to other innovative elements, such as the positioning of the qubba behind the iwan, the domed entrance hall and the plan to crown the portal with two minarets, the building is also outstanding for its water-supply system. Sultan Hassan used the nearby irrigation channel (to the north west of the building) to bring and distribute water to the various rooms of the madrasa and student lodgings located on different floors. Stone brackets, which used to hold the pipes bringing water to the different areas of the building, can still be seen along the length of the south west façade.

S.B.

Mosque and Madrasa of Sultan Hassan, qibla iwan, Kufic calligraphy on a foliated background, Cairo.

I.1.h Madrasa of Gawhar al-Lala

Gawhar al-Lala Madrasa can be reached from the Citadel Square (Salah al-Din) up a steeply stepped street behind the Mosque of al-Rifa‘i. This madrasa is next to the Madrasa of Qanibay Amir Akhur.

Opening times: all day except during midday and afternoon prayers (12.00 and 15.00 in winter, 13.00 and 16.00 in summer). The madrasa is currently being restored and visitors are not allowed inside.

The madrasa was built by Amir Gawhar al-Lala (al-Lala is the name given to the post of private tutor to sons of a sultan), civil servant in the palace of Sultan Barsbay. Gawhar al-Lala was an emancipated slave, at one point in service to the son of Barsbay, who died in prison suddenly as a result of an epileptic fit.

The madrasa was planned along the lines of the cruciform madrasas, popular at the time of the Circassian Mamluks in the 9th/15th century. Inside the building adjacent to the madrasa there is a sabil, kuttab and qubba in which its founder is buried, as well as storerooms and lodgings for the students and civil servants. The main entrance in the centre of the southwest façade overlooking Darb al-Labbana Street and the sabil, with its wall built of wood, is located in the southern section. It is of the type of sabil with a corner column, which came about in the 8th/14th century. The kuttab is typically located above the sabil and above the façade the minaret rises, built in a style called al-qulla or “knob” style, with a single balcony. On the western corner is the mausoleum qubba, the door to which is made of wood and distinguished by its copper decoration common to that period. The door, flanked by stone benches, leads to a derka (a rectangular hallway), from where via a bent passageway with a muzammala and a hidden door leading to Gawhar al-Lala’s house, is the durqa‘a. The Madrasa durqa‘a is decorated with marvellously coloured marble and covered by a decorated wooden lantern. It has two iwans and two sadlas, the largest iwan being that of the qibla.

G. G. H.

I.1.i Entrance of Manjak al-Silahdar Palace

Manjak al-Silahdar Palace is found at the beginning of Suq al-Silah Street, near the Armourers’ bazaar (al-Silah) next to Sultan Hassan Mosque.

Closed to the public, it can only be viewed from the outside.

This palace receives its name from Amir Manjak al-Yusufi al-Silahdar who held the post of amir al-Silah or amir of Arms during the era of Sultan Hassan. All amirs who held this title resided in the palace. Among them was Taghri Bardi, father of the historian Abu al-Mahasin, who was born there.

With the opening of Muhammad ‘Ali Street in the 19th century the palace was destroyed and today only the main entrance remains. Its pointed arch is framed by a surround of stone relief that narrows in the middle taking the shape of the Arabic letter mim. The arms of its founder, a circle divided into three sections with a sword in its centre, appears on the spandrels. The entrance leads to a derka previously covered by a sail vault, which rested on plain pendentives.

G. G. R.

Madrasa of Gawhar al-Lala, general view, Cairo.

I.1.j Entrance of Yashbak min Mahdi Palace

Yashbak min Mahdi Palace is located to the west of the Citadel, near Sultan Hassan Madrasa in Salah al-Din Square.

Closed to the public, it can only be viewed from the outside.

Madrasa of Gawhar al-Lala, marble courtyard floor, Cairo (painting by Mohammed Rushdy).

Though nowadays only the main-entrance, part of the great hall and a few other vestiges remain from the 7th/14th century palaces, the Palace of Yashbak min Mahdi is the best conserved of the amirs’ residences. Built for Amir Sayf al-Din Qusun, saqi (cup bearer) and sonin-law of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun, it was nevertheless used by those who held the post of atabek or commander-in-chief of the armies. Amir Yashbak min Mahdi was the first Mamluk to hold simultaneously the posts of First Secretary, Regent of the Kingdom and Commander-in-Chief. During his period of residence in the palace in the Qaytbay period, he had it restored in around the year 880/1475.

Entrance to Manjak al-Silahdar Palace, Arms of its founder, Cairo.

The majority of what can be seen today dates back to this period. The ruins are on the same site as the palaces of the amirs, near the seat of government in the Citadel. In those times, the proximity of the amirs’ palace to the Citadel was proportional to the importance of his post, hence the location of this residence, belonging to the atabek of the armies.

Entrance to Yashbak min Mahdi Palace, Cairo (painting by Mohammed Rushdy).

The magnificent portal, second only to that of the Mosque of Sultan Hassan, opens on the north west façade, where the main entrance is crowned by a trilobed arch of coloured marble with decorative motifs carved in stone. An inscription on the entrance with the names of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun and Amir Yashbak min Mahdi provide us with information about the different stages of construction and reconditioning of the palace.

The deep recessed portal crowned with an extraordinary stalactite vault supporting a ribbed cushion dome, bears the name of two artists, Muhammad Ibn Ahmad and Ahmad Zaghlish al-Shami the Syrian, both of whom took part in its construction.

The solid vaulted halls of the lower floor served as stables and storerooms and upheld the sumptuous reception hall and other rooms above it. The reception hall adopted the traditional design of a large covered courtyard (durqa‘a), of some 12 m. across, with wide iwans along its length and sadlas along its width. Despite the state of ruin in which it finds itself today, the importance of this palace can be deduced from the quality and size of the pointed horseshoe arches, with their al-ablaq stonework giving us a clear idea of the dimensions of the original building. It is easy to imagine the splendid marble paving, the carved wooden ceilings with their gold and paint work, the central fountain, the glass windows and the turned wood screens which in previous times adorned its interior.

G. G. R.

Entrance to Yashbak min Mahdi Palace, detail, Cairo.

Entrance to Yashbak min Mahdi Palace, naskhi inscription, Cairo.

MAMLUK DRESS

Salah El-Bahnasi

Mamluk Sultan, (painting by Mohammed Rushdy).

Mamluk clothing was characterised by designs and decorations that varied according to use or occasion. Clothing formed part of one of the largest industries of the times: the weaving industry.

This included the manufacture of silk and in particular of patterned materials created with carved wooden printing stamps. Alexandria became famous for the weaving trade and in the words of al-Qalqashandi, the historian, the cloth manufactured there was without equal in the world. Sultan al-Ashraf Sha‘ban visited the workshops in Alexandria, and was deeply impressed.

With each social class being identified by a particular style of dress, Mamluk garments were produced in great variety. In addition to this, diplomatic and trading relations between the Mamluks and Europe, India, Iran and China brought further variety to manufacturing and favoured the importation of designs from these countries. Many decorative elements on Mamluk clothing found their inspiration in art forms from Europe and the East.

The garments used by the different social classes of the Mamluks, characterised by their warrior spirit, were associated with military equipment, above all suits of armour, swords, and helmets, shields and axes, which were only displayed on festive occasions.

The Sultan’s official dress comprised a turban and black jubbas, and a gold belt from which hung a sword. The use of black was considered a sign of loyalty to the Abbasid Caliph, for the Standard of the Abbasid State was of the same colour. On occasions, the sultan would don a fur-lined coat over a woollen or silk garment embroidered with gold thread; on other occasions he wore velvet, and in the summer, white vestments.

Amirs wore the fez rather than the turban as a head-dress, which like the cape or cloak was reserved for religious men. In winter they would wear cloth cloaks (al-jukh) known as jukha.

Mamluk woman, (painting by Mohammed Rushdy).

On Fridays the khatib, or prayer leader, would wear black garments, carry a banner of the same colour and a sword, a sign of his rank. Silk garments, however, were deemed to infringe religious law. Muslim religious figures wore white turbans whereas their Christian counterparts wore blue, and Jews yellow. These colours extended to Christian and Jewish dress in general. Qadi (judges) and learned men wore garments characterised by long loose-fitting sleeves. The majority of men also wore a turban and a cotton tunic, with a low neck and long sleeves. Turbans were on occasions used to carry coins, making them a common target for thieves and bandits.

Dress for women consisted of a long chemise and loose fitting pleated trousers over which a dress or tunic was worn. Women wore a loose-fitting white cloak, known as izar, and a headscarf. With the exception of dancers and singers, women also wore the hijab (veil) to cover their faces.

Mamluk-period dress generally stands out for its extravagance, often using imported animal furs and skins, and gold or silver adornments. One story has been passed down through the ages recounting how the wife of Sultan Baybars ordered a dress for her son’s (al-Aziz Yusuf) circumcision ceremony costing 30,000 Dinars. For each separate dress type there was a special suq with its own artisans. Amongst the most important markets is the al-sharabshiyyin suq, specialising in head-dresses for the sultan, amirs, viziers and judges.

SPORTS AND GAMES IN THE MAMLUK ERA

Salah El-Bahnasi

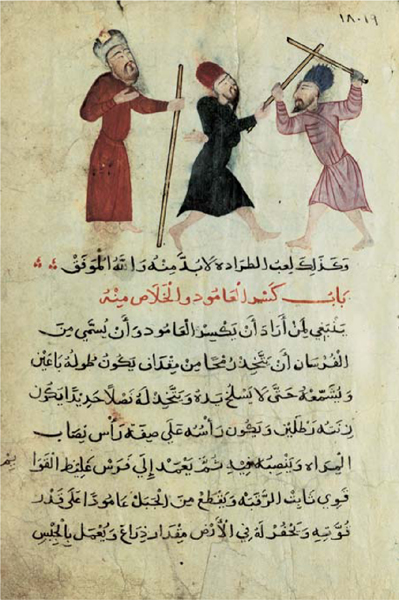

Manuscript on horse riding and fencing, fencing scene, 9th/15th Century, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 180199), Cairo.

In accordance with the overriding principle of “the survival of the fittest” in the times of the Mamluks, they placed great importance on acquiring such virtues as valour and fortitude by means of sport. Horse riding formed an essential part of these activities, for soldiers, amirs and the sultan himself. As such, Mamluk governors, and in particular al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Qalawun, spent enormous sums of money on the purchase of excellent horses. A special administrative unit

(known as al-rikkab khana, or horsemen’s rooms) was established to take care of the sultan’s stables.

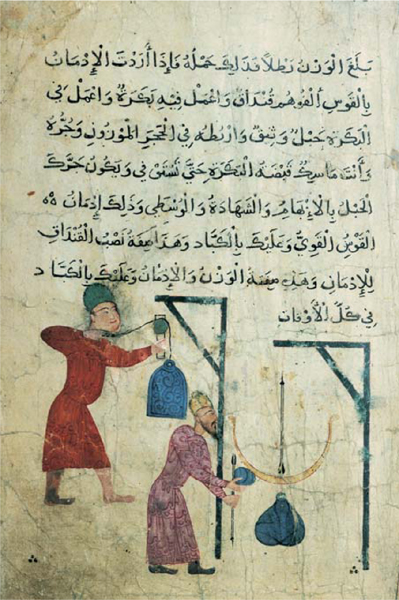

Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay made sure that, as well as the Mamluks, other sectors of society would learn to ride. Among the many events of the closing ceremony in the equine games during the reign of al-Ashraf Qaytbay, the main event was the day of the procession in honour of the convoy that was to carry the Kiswa to Mecca. Among many principles, Islam promotes that of horse riding. There is not a better example of the importance of horses in Mamluk times than the positioning of the suq dedicated to their sale near the Citadel – the seat of government. The more than 7,000 horses left behind on Sultan Baybars’ death bear even greater testimony to their importance. The al-Baytara manuscript (veterinary science; the profession and art of shoeing horses) conserved in the Egyptian Library contains an illustration of two riders racing. The Museum of Islamic Art houses another manuscript displaying equine games and fencing dating back to Mamluk times. Manuscripts dedicated to horse riding also bear scenes of fencing between two contenders accompanied by a third holding a pole seemingly acting as referee.

Of the most attractive sports for the Mamluks was qabaq. This consisted of firing an arrow at a gold or silver recipient, inside which a dove was placed. Whoever hit the target – decapitating the dove – won the competition and was awarded the gold recipient as a trophy. A special area on the edge of Bab al-Nasr was reserved for the practice of this sport. An illustrated Mamluk manuscript dating from the year 875/1471, kept in the National Library in Paris, shows two horsemen aiming their arrows at a target – a recipient placed on high ground.

Hunting was another of the Mamluks’ favourite sports and was considered a manifestation of power and prestige. Specially trained birds and dogs were used in the hunt, as well as firearms. The prey caught was considered among the most precious presents exchanged between the governors of the time. It was customary to hunt during the spring. Furthermore, hunting was not considered simply a sport, but also a form of entertainment, and singers, musicians and jesters usually accompanied sultans on a hunt. From time to time, however, such events would end in disaster. Once outside the protection of the city, enemies of the sultan would take the opportunity to do away with their master; a fate Sultans Qutuz and al-Ashraf Khalil were to meet.

Manuscript on horse riding and fencing, weight-lifting scene, 9th/15th Century, Museum of Islamic Art (reg. no. 18235), Cairo.

Sultans were also passionate about ball games and especially jawkan, a sport played on horseback with a long pole with a curved end. Sultan Baybars was said to play three matches a day on Saturdays during the festivities that followed the annual flooding of the Nile. Such was the interest the Mamluks had in this game that certain civil servants were chosen and given special tasks for this activity, such as the jawkandar, in charge of having the sultan’s playing equipment ready. Mamluk works of art show scenes inspired by the sport. Examples can be seen on a gold and silver inlaid brass recipient from the end of the 7th/13th century, kept in the Panaki Museum in Athens; also on an enamelled glass bottle in the Islamic Museum in Berlin.

Swimming was another important sport of the times and skill was demonstrated by swimming across the Nile from bank to bank. One of the sultans most famed for his skill in this sport was al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh. Wrestling had many followers, but it was reserved for amirs and not for sultans given the inappropriate postures required.