APPENDIX

Methodology

THE LAW AND POLICY STUDENT POLITICAL AMBITION STUDY (LPS-PAS)

The goal of this project’s methodology was to find a subset of the population that would be well-positioned to run for office but who had not (yet) run. I hypothesized that whatever “candidate-deterrence effects” exist would be visible earlier in life than previous samples have tested (more details on previous samples/surveys will follow). I therefore sought young adults, but ones who had already made key decisions about their career directions by choosing a graduate school program in law or policy. The ideal sample would therefore come not just from law and policy schools but also from high-ranking programs.

The use of students from top-tier law and policy schools equalizes to a large degree (although certainly not entirely) the structural factors that tend to give certain candidates (and especially white men) a competitive edge. Yet this project hypothesizes that gender and race differences should still persist, even among elites. The design chosen minimizes SES effects in the attempt to isolate effects of race, gender, and then race–gender intersectionality. The data in this sample allow me to investigate the multiple factors working simultaneously that correlate with depressed political ambition among women in general, and women of color in particular, through comparisons with similarly situated men.

SITE SELECTION

The three specific schools chosen for sample recruitment were Harvard Law School and Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government (which together produce a number of national political leaders) and Suffolk Law School (which produces many Massachusetts political leaders). The Harvard schools were a natural choice, given their reputations and the likelihood that these schools would attract extremely ambitious students across race and gender. Harvard Law and Harvard’s Kennedy School are also well known as conduits into national-level governmental positions. Harvard sends a significant number of its graduates into politics and government in the United States. More U.S. presidents have attended Harvard than any other university; seven presidents, including current President Barack Obama, attended Harvard Law School.1 Currently, 47 Harvard affiliates hold U.S. congressional seats, constituting slightly less than 9 percent of the congressional body and more than double that of any other university.2 Each Congress for the past two decades has had at least 34 Harvard alumni in its ranks, peaking at 48 in 1995.3 Twelve percent of U.S. attorneys general have been Harvard graduates (more than any other single university).4 At the state level, Harvard has the largest number of alumni in legislative statehouses across the country (totaling 104 in number).5

Looking specifically at graduates from Harvard’s Kennedy School: a substantial portion of its graduating classes each year enters the public sector. Between 2001 and 2012, of those who reported employment, the Kennedy School sent an average of 46 percent of its graduates into government jobs, with a low of 38 percent in 2011 and a high of 59 percent in 2002.6

I chose Suffolk Law after collecting data on current state legislators in Massachusetts and finding that Suffolk Law is the modal degree: forty-two percent of Massachusetts state legislators with a JD come from Suffolk, a far higher proportion than the next closest competitors, New England School of Law and Boston College Law.7 (Not all state legislators have a JD, but it was the most common form of graduate degree, held by 47 percent of Massachusetts state legislators.8) Suffolk Law, then, is the largest “feeder” of graduates into state-level politics, just as Harvard—specifically Harvard Law and Harvard’s Kennedy School—is the largest “feeder” of graduates into national-level politics. The Suffolk data also serve as a check on the Harvard data, to test which effects might be Harvard-specific and which may be more generalizable to the population of elite law students. Likewise, the Harvard Kennedy School data serve as a check on the data from the two law schools, to test for differences between highly ambitious JD students and their non-JD but still policy-minded counterparts.

Together, these students from elite law and policy schools constitute an ideal sample; they are, on the whole, relatively high-SES young people, who are mostly unmarried and childless (thus minimizing the effects of work–family conflict). Most notably, the work of the admissions committees of these schools ensures a far closer “match” between men and women, and between whites and nonwhites, than we would find in a representative sample from the general population or in many other institutional settings.

SURVEY RECRUITMENT

Between 2011 and 2014, I conducted an original web-based survey of law and policy school students from the three previously-described campuses. Of the 777 collected surveys, 764 were usable; the rest were omitted because of incomplete responses or because the respondents were not U.S. citizens (a prerequisite of sample inclusion). I supplemented the survey data with one-hour interviews with more than 50 survey respondents, varied by race, gender, year, and school, to further understand respondents’ interest in and reactions to politics and to a possible political candidacy.

I began the project by launching the survey in April 2011 at Harvard’s Kennedy School, with a sampling frame of 330 students, from which I had a 60 percent response rate, resulting in a sample of 217 students who took the survey. I then replicated the process at Harvard Law (with a response rate of about 62 percent, resulting in a sample of 330) and Suffolk Law (sample of 150 respondents).9

Recruiting only from uncompensated volunteers for this survey could skew the results, as it might mean that only students already interested in politics would take the survey. Because I wanted to capture the politically uninterested as well as the interested, and the politically unambitious as well as the ambitious, I used funding from several grants to provide incentives to all respondents. Funding for survey recruitment incentives was generously provided by grants from IQSS (The Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard), CAPS (the Center for American Political Studies at Harvard), the Ash Center for Democratic Governance at Harvard’s Kennedy School, and Marie Wilson. With this assistance, I was able to promise each survey respondent a $10 reward (in the form of a coupon for Amazon.com or Starbucks) for taking the fifteen-minute survey.

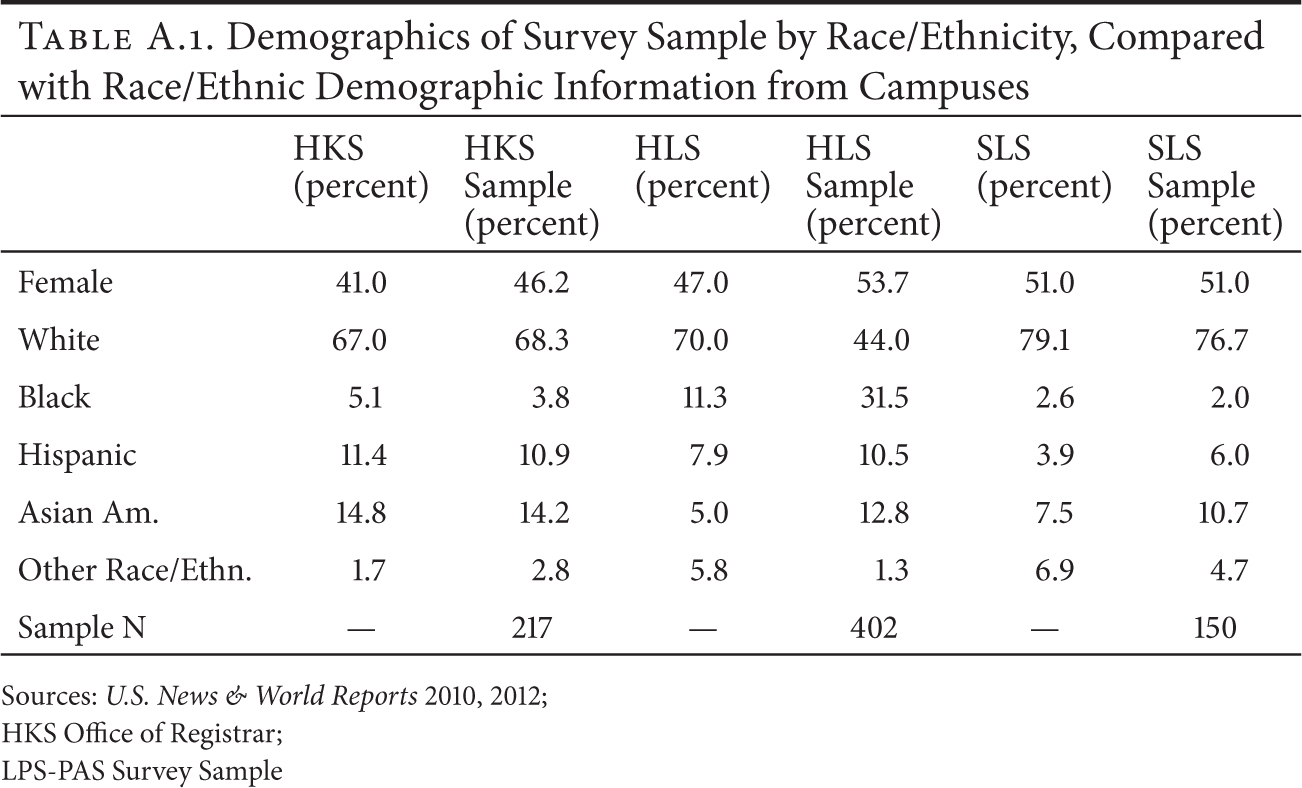

A reward of this magnitude for this amount of time works out to a rate of $40/hour, which is a competitive wage for law and policy students, and it ensured a good participation rate in my study. It is, however, neither coercive nor out of line with the kinds of salaries such students might expect from summer jobs with law or consulting firms. The incentive should make us trust the data more, as it maximized participation from those who might otherwise have passed over a survey request with “politics” in the title. Table A.1 gives basic demographic data about the sample from each campus, compared with the known demographics of the students at that campus as a whole.

Overall, both Harvard’s Kennedy School and Suffolk Law under-represent domestic minorities as students, making an intersectional race–gender analysis more difficult because of a low-n problem. However, Harvard Law School has a relatively large proportion of black American students, and I oversampled these, which greatly increased the number of black respondents in my survey sample. My sample also includes a fairly good proportion of Asian American students, and a lower but still testable number of Hispanic students, allowing some comparisons to whites and to other minority groups. Regarding gender, the sample is 51 percent female at both of the law schools, and 46 percent female at Harvard’s Kennedy School. This percentage is comparable to the student populations at all three schools.

WEIGHTING DATA BY RACE

The survey design called for stratified sampling. Where possible (which turned out to be only at Harvard Law), I collected the names and e-mail addresses of every student and information about each student’s racial/ethnic background. Race was observer-coded by me and checked by at least one research assistant, to divide the sample into two major groups: those who we were pretty sure were white/Anglo/Caucasian, including Jewish, and those who appeared to have some other kind of racial or ethnic background (East or South Asian, Native American, black, Hispanic). I drew a random sample from the list of white students and Asian, of whom there were many to choose, for sampling, and included the entire list of black and Hispanic students in the sampling frame. The response rate for this campus was 62 percent, resulting in a sample of 402 responses.

For the Harvard Kennedy School sample, as the MPP program was much smaller (I received one list of all 330 students then enrolled), I included the entire list of both white and minority students as the sample for that campus. I received a 60 percent response rate at this campus, resulting in a sample of 217 students who took the survey (211 of which resulted in usable responses).

At Suffolk, where names and e-mail addresses were not available because I was not a student at that university, I recruited through three methods: (1) an e-mail request that the Dean of Students sent as part of a weekly newsletter (which included for several weeks/issues my announcement of paid survey recruitment); (2) posters I put up all around the Suffolk Law campus with pull-off tabs announcing the survey and payment, with my e-mail address on each poster and each pull-off tab (those interested e-mailed me and once I ensured from their e-mail addresses that they were Suffolk Law students, or asked them to write from their official Suffolk Law addresses if they had not done so at first, I sent them a web link for the survey); and (3) I hired a Suffolk Law student to recruit participation in the survey through the race- and ethnicity-based student clubs, like the Black Law Students Association. This resulted in 150 usable responses from this campus.

The resulting survey sample as a whole (for all three campuses) contains a good oversample of minority students, such that the sample is 57.2 percent white and 42.8 percent minority. But the large bulk of the black and Hispanic students come from Harvard Law and were recruited in a different manner than the white and Asian American students in that sample. I therefore calculated and applied sample weights.

CALCULATING AND APPLYING SAMPLE WEIGHTS

Because not every student had had an equal chance of being included in the sample, in the interests of achieving black and Hispanic oversamples, I calculated sample weights to be applied only to those who were oversampled (black and Hispanic students at Harvard Law School). The calculation allowed me to underweight the responses of black and Hispanic students from Harvard Law School (who were oversampled), and overweight the responses of black and Hispanic students from Suffolk Law and Harvard’s Kennedy School. This necessitated knowing the proportions of both of these groups not only in my sample but in the overall school populations from which the sample was drawn. Having obtained these figures about each school’s population from their admissions offices or outside sources, I calculated sample weights (“pweights”) by dividing the population percentage by the sample percentage.10 I then applied these pweights to each analysis where possible (means, correlations, and regressions). In the book text, the first time I refer to a sample mean, I use the term weighted, with a footnote to explain, and to indicate that from then on all means would actually be weighted means, without my saying so each time.

INTERVIEW METHODOLOGY

Interview respondents (n = 53) were recruited from those who took the survey. A “thank-you” screen at the end asked those interested in discussing these questions further, for an additional $20 incentive, to contact me. With interviews that usually took forty-five minutes to one hour, this worked out to compensation at a rate of between $20 and $27 per hour—not as high as for the survey, but still a reasonable rate of pay for their time.

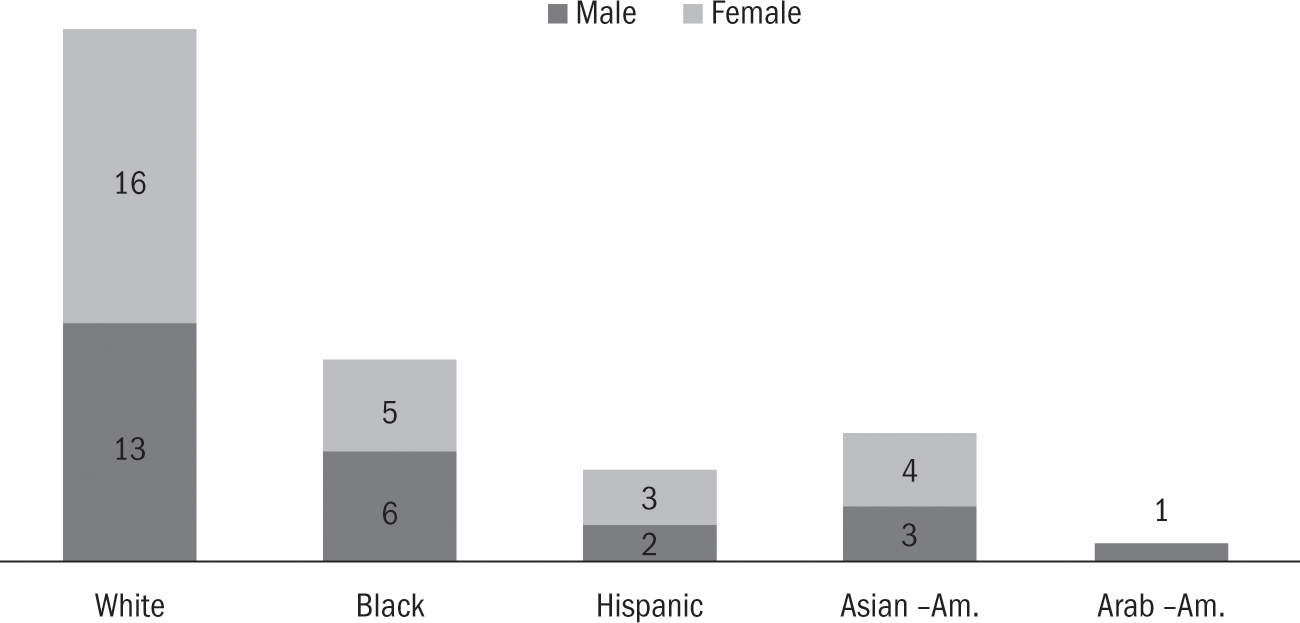

I selected the interviewees from among those survey respondents who, after taking the web-based survey, responded to a request to talk with me further about the questions in the survey. In that choice, I considered gender, race/ethnicity, school, and year in the school’s program, to achieve a diverse mix. I ended up interviewing more than 70 percent of those who volunteered for an interview, with the interviewees I passed up being mostly white in my quest for racial diversity. Figure A.1 presents demographics from the interview sample.

Figure A.1. Interview Sample, by Sex and Race/Ethnicity (n = 53). Source: LPS-PAS, Interview Sample.

I generally met interviewees at a coffee shop on or close to their campus, or in my office or a room in their campus’s library if they asked for more privacy. With respondents’ permission, I audiotaped each interview and transcribed the full file, then deleted the audio recording to preserve respondents’ confidentiality.11 I coded each transcript and analyzed the quotes for each code, as well as analyzed the transcripts more holistically. Figure A.1 gives demographic (race and gender) information about the sample of interviewees for this project.

SAMPLE VERSUS GENERAL POPULATION

The students of the two Harvard schools and Suffolk Law School constitute an elite sample; as much as possible, this project attempts to minimize the role of SES (which previous studies have shown to be perhaps the most powerful factor in explaining political participation) so as to study the effects of other factors—in particular, race, gender, and perceptions/expectations of elections and holding office. The sample is representative of U.S. political candidates—who, as research has documented, are more educated, wealthier, more partisan, and more politically active than those in the general population.

Several studies have conducted surveys of elite populations of eligible candidates, in the same vein as the LPS-PAS. Two of the most notable come from Lawless and Fox (2005) and Stone and Maisel (1997–98). Recently, Broockman and colleagues have collected data from the first-ever “National Candidate Study” (2012), drawing from 10,000 declared state legislative candidates. Table A.2 gives demographic and political engagement information about each previous study’s sample in the first three columns and the LPS-PAS sample in the fourth column.

Previous samples of potential candidates have tended to be whiter and more male than the general population (which is also true of actual candidates—see the National Candidate Study data from Broockman et al.). The LPS-PAS sample of eligibles, however, intentionally over-represents people of color and women, as the project’s original questions centered on these groups. My sample is also intentionally younger than other samples in this vein, to look for effects “upstream” of earlier research. Relatedly, the LPS-PAS sample is more Democratic than previous samples of candidates and potential candidates, as is true of this age group more generally. Otherwise, as table A.2 shows, my sample is in line with previous samples of eligibles and declared candidates in terms of unusually high incomes and levels of education.

SURVEY AND INTERVIEW INSTRUMENTS

The original survey and interview questionnaires for this project were approved by Harvard’s IRB (Institutional Review Board) in December 2010 and reapproved each year up to 2014 while I collected several rounds of data to ensure a sizeable and diverse sample. Both instruments were beta-tested extensively among then-current Harvard students of various schools. The survey instrument (available from the author upon request) contained many original questions and also replicated questions from several previous surveys, including the ANES (multiple years); Verba, Schlozman, and Brady’s “Citizen Participation Study” (1990), and Lawless and Fox’s “Political Ambition Study” (2005). The instrument contained items testing for:

- a) Education factors: current program, parents’ education levels, subjects’ high school experience(s) (such as whether the high school was single-sex and how racially mixed it was);

- b) Demographics: race, gender, citizenship, religion/religiosity;

- c) Childhood and background factors: family income, whether subject grew up in a rural, suburban, or urban environment; how racially mixed the subject’s neighborhoods and high schools were; R’s history of participation in high school and college activities;

- d) Personality and psychological self-assessments: how subject identifies on a number of traits linked to gender and/or race, including ambition, confidence, competitiveness, and willingness to take risks;

- e) Political socialization factors: parents’ political and civic activity; subjects’ child and early adulthood political engagement and participation;

- f) Experiences of discrimination, based on race and/or gender (including harassment).

- g) Current political factors and engagement: interest and participation in political activity; party affiliation and ideology self-placement scale;

- h) Policy stances on two major political issues (abortion and income inequality);

- i) Perceptions of politics, politicians, and officeholding: whether subject thinks politics is useful to solve problems, trusts government, and thinks politicians can make positive change;

- j) Running-for-office variables, including: willingness to consider running (even at some point in future); level of office in which subject might ever be interested; and reasons why subject would or would not run; and

- k) Perceptions of discrimination/disadvantage in politics: whether subject anticipates barriers/burdens; does subject think whites versus minorities and men versus women have advantages or disadvantages in campaigns.

TABLE A.2. Selected Characteristics of Potential and Actual Candidate Samples |

||||

Maisel & Stone “Potential Candidates” Study (1997–98) |

Lawless & Fox “Eligibles” Study (2001–2) |

Broockman et al., “National Candidate Study” (2012) |

Shames LPS-PAS (2012–14) |

|

Demographic Background |

||||

Male |

77% |

53% |

72% |

50.5% |

White |

92% |

83% |

81% |

66.1% |

Graduate or Professional Degree |

63% |

(see Note 1) |

45% |

(all pursuing one) |

Age |

47% aged 50 or more |

48.5 (mean) |

55–64 (median range) |

27 (median) |

Family Income $90,000 or Higher |

54% |

(see Note 2) |

$96,000 mean income for sample |

46% (see Note 5) |

Political Background |

||||

Identify with Democratic Party |

59% |

45% |

55% |

61.3% |

Identify with the Republican Party |

41% |

30% |

45% |

10.1% |

Identify as Liberal |

30% |

NA |

37% |

63.6% |

Identify as Moderate |

19% |

NA |

18% |

23.6% |

Identify as Conservative |

51% |

NA |

45% |

12.8% |

Active in Political Campaigns |

54% |

(see Note 3) |

67% |

23.6% |

N |

1,708 (see Note 4) |

3,614 |

10,000 |

763 |

Sources: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample; Maisel and Stone 1998 (see Note 4); Lawless and Fox 2005; Broockman et al 2012 Note 1: Lawless and Fox 2005 does not publish this percentage, but the “average education score” for their sample was a 5.4 out of a possible 6, suggesting that most of their sample had postcollege education. Note 2: Lawless and Fox 2005 does not publish this percentage, but the “average income score” for their sample was a 4.6 out of a possible 6, suggesting (as with the other samples) a family income significantly higher than for the U.S. population average. Note 3: Lawless and Fox 2005 does not publish this percentage, but the “average participation score” for their sample was a 5.5 out of a possible 9, drawing on a list of nine possible political activities. Note 4: For this sample, table only gives data for first-time “named candidates,” not the state legislators who were positioned to move up to Congress. Note 5: The LPS-PAS instrument gave income categories rather than allow students to enter their family income manually, in the interest of accuracy and response rate. However, the income categories do not exactly match up with those given in the other surveys listed here. This percentage for the LPS-PAS sample gives the percentage of people whose families earned $100,000 or above rather than $90,000 or above. |

||||

To categorize subjects racially, I used the current U.S. Census series of questions on race/ethnicity. I first asked respondents to identify as ethnically Hispanic or not, and then (if yes) what type of Hispanic origin (with great detail in answer choices). I then asked their racial category (black, white, Asian, with a fine degree of detail under Asian). For purposes of analysis, I folded all Asian respondents into a category I call “Asian American,” and respondents with Hispanic ethnicity origins into the category “Hispanic.”12 If respondents self-identified as being both white and of a nonwhite race, I classified them for data analysis purposes into the nonwhite group.

This combination of survey and in-depth interview data makes possible an analysis of young elite eligible candidates’ expectations of both positive and negative factors in the electoral environment and legislative institutions, including those relating to race and gender, and their expectations about the usefulness of politics to effect positive change. The data shed light on the ways in which structural barriers and perceptions of political usefulness shape eligible candidates’ willingness to consider a political campaign seriously.

For those interested in using the survey dataset, it will soon be available for public use from the Harvard Dataverse, through the Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Science (IQSS), at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/.