2

Political Ambition

What It Means and Why We Should Care

Representative democracy requires many things, among them free and fair elections, civil rights for citizens, constraints on executive power, and a free and independent media.1 Critically, we also need people who are ready and willing to run for office (candidates)—and preferably enough of them to create good electoral competition. The better the competition, we hope, the better will be the quality of those who eventually assume office. An ideal democracy would have a bounty of high-quality, competitive candidates among whom voters could select. Even if the sovereign citizen’s only real duty is to say yes or no2 to a particular candidate, democracy can still thus afford meaningful choice among candidates, parties, and policies. This theory starts to break down, however, if we lack good candidates. A shortage of those who would be high-quality candidates, manifesting either as a shortage of candidates overall or an oversupply of low-quality candidates, constitutes a serious problem for our democracy.

Recruitment into political candidacies in the United States relies mostly on would-be candidates’ stepping forward relatively independently. In stark contrast to most developed democracies, the United States has “candidate-centered politics” rather than a party-centric system.3 Citizens rarely become candidates without some (and often a large) degree of self-recruitment. Although parties are quite important in most election and governance processes, our parties here, compared with their counterparts in other democracies, have relatively little control over who will run under their name. U.S. democracy is not simply the “competitive struggle for the people’s vote”4 but also the prior competition over who will wage that struggle. For better or for worse, candidate selection—one of the most critical functions of elite party decision makers in other countries—is “crowd-sourced” in the United States. As political scientist Joseph Schlesinger argued nearly half a century ago in his classic treatise, “Ambition lies at the heart of politics.”5

This means that, in contrast to a system wherein it is the job of the party to convince someone to stand for office, in the United States we need people who self-identify as wanting to run. Those who run are therefore distinguished first and foremost from those who do not by their ambition to hold office. Summing up the lesson learned from a multi-year study in a book called Political Ambition, political scientists Linda Fowler and Robert McClure write, “Ambition for a seat in the House, more than any other factor—more than money, personality, or skill at using television, to name just a few examples—is what finally separates a visible, declared candidate for Congress from an unseen one.”6

More specifically, this ambition means that those who run find politics meaningful or useful. Sue Thomas, an expert on women and U.S. politics, explained in her book How Women Legislate, “[T]he very choice of joining an organization (assuming a certain level of choice was operational) signifies that the person doing the choosing considers the organization or its goals to be generally valuable and legitimate.”7

On the one hand, this produces a surprisingly open system, one in which ambitious, charismatic candidates can rise quickly from relative obscurity, even against the wishes of party bosses. The political career of Barack Obama makes the point nicely; in few other comparable democracies could a politician with so little electoral experience attain a country’s top office. Recent Tea Party candidates similarly illustrate the system’s permeability and the parties’ relative lack of control; inexperienced candidates have won their parties’ primaries in several high-level elections in just the past few years, going on to embarrass their parties in the general election. American history is rife with examples of such “outsider” candidates (Donald Trump in the current election springs to mind), either within the two major parties or as third-party candidates who then help to chart a new direction for one of the main parties. With enough will and work, would-be candidates in the United States, even outsiders, can often overcome the barriers to entry.

On the other hand, as open as the U.S. political system may be in some ways, the crucial individual will to run—more important here than in other democracies—is distributed neither evenly nor widely. The barriers seem steep, even insurmountable or not worth surmounting, to many who would make good political candidates and able public servants, if only they would run. Aversion to running for and/or holding office, particularly if differentially distributed across politically relevant groups, can constitute a serious problem for a democracy. Schlesinger wrote, “A political system unable to kindle ambitions for office is as much in danger of breaking down as one unable to restrain ambitions. Representative government, above all, depends on a supply of men so driven.”8 In other words, our ability as citizens to select good leaders through an electoral process is constrained by those who choose to run. I suppose I could still vote for you as a write-in candidate, even if you did not want to run, but that is a technicality. Realistically, if you do not want to run, you meaningfully constrain my ability to vote for you. And if you would have been the best candidate, too bad for me.

A candidate-centered democracy, then, is only as good as the candidates who choose to come forward to stand for office. Reflecting in Who Runs for Congress, political scientist Thomas Kazee mused that his discipline has “long assumed that ambition for public office in America is widespread, that the number of people seeking elective positions is adequate to ensure both a steady supply of able public servants and a level of electoral competition sufficient to hold officeholders accountable for their actions.” What if this is not the case? Candidate emergence and its lack may be, as Kazee argued, the “key to understanding American politics.”9

The candidates we currently see run—those generally most ambitious to hold office—are a narrow and unrepresentative bunch of those who could run. Both factors (narrow and unrepresentative) are concerning. Representative government is strengthened when representatives share experiences and understandings with their constituents. An unrepresentative group of candidates vastly reduces, in important ways, the likelihood of the resulting elected officials’ being like those they represent.10 Indeed, a current crop of candidates, as measured in 2012 in a 10,000-person study of candidates at all levels of office, is unrepresentative of the American populace in multiple ways, especially in terms of race, sex, and class.11

So much for unrepresentative—what about narrow? That the pool of the politically ambitious is small could by itself be a problem if it meaningfully reduces competition for the seats, which could reduce the quality of those eventually chosen. And a small pool can also be a problem for democracy if it means that seats go uncontested, which turns out to be the case in a fairly large and apparently increasing proportion of elections, not so much at the national level but lower. A 2012 William and Mary College study found that only about 60 percent of state legislative elections offered voters a choice between major-party candidates.12

Finally, a narrow, unrepresentative pool of candidates suggests a loss of talent sorely needed to solve major national and international political crises. It could mean that people who would be excellent political leaders are choosing not to run, for reasons we have yet to fully understand. I here argue that such choices are rational, given the balance of negative to positive perceptions on the part of most potential candidates about candidacy, politics, and government. If young people—and especially young women—are averse to running, in other words, it is not because they are irrational.

Anticipating Running for Office

Anticipation is a critical concept in political science. In an address to the 2000 American Political Science Association, renowned political scientist (and then-president of the association) Robert Keohane urged political scientists to pay greater attention to the role of what he called “rational anticipation.”13 As he put it, “Agents, seeing the expected consequences of various courses of action, plan their actions and design institutions in order to maximize the net benefits that they receive.”14 The idea is not radical; it represents the essence of rational-choice thinking. To make rational choices, individuals rely on anticipation, and therefore perceptions.

Douglas Arnold made the same point in his theory of how and why members of Congress act as they do: they are anticipating the response of constituents, even in the absence of any constituent knowledge of their actions. “The cautious legislator, therefore, must attempt to estimate three things: the probability that an opinion might be aroused, the shape of that opinion, and its potential for electoral consequences.”15

Before both Keohane and Arnold, back in the 1950s, economist Anthony Downs had articulated a famous theory of rational action as applied to voters. Downs was careful not to equate being “rational” with being “inhuman.” His “rational man” still has feelings, prejudices, and illogical thoughts—but “[moves] toward his goals in a way which, to the best of his knowledge, uses the least possible input of scarce resources per unit of valued output.”16 The benefits for a rational actor must outweigh the costs—and the rational actor’s “best knowledge” (what I call “perceptions” on the part of eligible candidates) is more critical for prediction than the objective reality, although it is based upon the objective reality.

Turning his attention to why people vote, Downs offered a series of equations describing the rational actor’s utility functions in voting or abstaining. His logic runs into a problem explaining the rationality of an act that has costs (voting) but few apparent benefits. The rational actor, he assumes, will correctly perceive that if no one votes, the democracy in question will collapse—but if the voter is that perceptive, she will also figure out that as long as someone else votes (and someone else always will), she won’t have to. Ultimately, Downs resorts to adding a new term to his model, on the benefits side; many citizens, he explains, derive a psychological reward from the continuing existence of democracy, and this is often (but not always) large enough to counterbalance the often-small costs of voting. (Riker and Ordeshook, later interpreters of Downs, called this the “D-term,” for the reward of doing one’s civic duty.17)

In my own work, faced with data suggesting high and rational perceptions of multiple, expensive costs to running, at first I had trouble explaining why logical actors would decide to be candidates. I discovered that the solution, for a small and unrepresentative bunch in my sample, had to do—as in Downs’s model—with finding perceived rewards that offset the perceived costs. Those who want to run perceive benefits from politics and political candidacy that are not shared by those deterred from running. I elaborate more on the specific content of these costs and benefits in later chapters.

Just as with Arnold’s “cautious legislator” and Downs’s “rational voter,” previous studies find that potential candidates are careful and thoughtful about whether and when they run. We know, for instance, that incumbents regularly collect large “war chests” of campaign funds that rationally deter challengers, including high-quality challengers.18 We know also that minority candidates are more likely to emerge in majority–minority districts than in white districts.19 Research also stresses the importance of eligibles’ perceptions of winning. Studying strong potential challengers for House seats in the mid-1990s, Maisel and Stone write that the challengers were “most strongly influenced by what they perceived to be the chances of winning their party’s nomination in their district.”20 Women may be more “rational” in this sense than men; studying state legislators who flirted with the idea of running for Congress, Fulton and colleagues find that the female legislators were more sensitive than their male counterparts to “the strategic considerations surrounding a candidacy.”21 Similarly, Lawless and Fox found in a matched sample of male and female eligibles, the women were less likely to think they would win should they run.22

Like the eligibles studied in this research, the young potential candidates in my study have thought ahead. About half (47.7 percent) had already been asked to run for office. A majority (63 percent) had thought about running, even if not seriously. My subsequent analysis shows that their perceptions of costs and benefits line up with their desire to run. Their political ambition strongly relates to a rational cost-benefit calculus much like that employed in a Downsian model or in other rational-actor models of political participation more generally.23 Nearly all (92 percent of the sample on average) called themselves “ambitious,” but they were not equally politically ambitious. My data analysis explores the differences and the rational reasons why some show an interest in running while most do not.

Gaps in Who Runs: Sex, Race, and Class

I think it’s very tough because I think society has kind of ingrained that it’s like politics is kind of a male-dominated industry.… I think it’s definitely become a more even playing field, but I think white males still dominate.

—John, white male JD candidate, Suffolk Law School

The United States is a country of astonishing diversity, yet public offices continue to be overwhelmingly dominated by white men. Although women constitute a majority (51 percent) of the U.S. population,24 they make up only 25 percent of state legislators, 18 percent of big-city mayors, 19 percent of members of Congress, and 12 percent of state governors.25 People of color are a growing third of the population, yet they hold less than 15 percent of elected political positions.26 Across states, 9 percent of all state legislators are black, 3 percent are Hispanic, 1 percent is Asian American, and 1 percent Native American.27 Under-representation by race and gender characterizes government bodies at all levels, but especially at the top; the U.S. Senate is 94 percent white and 80 percent male.28

One of my interviewees, Matt, a student at Suffolk Law School, proposed a useful test for visualizing such gaps. When asked about the current ratios of men to women or whites to nonwhites in Congress, he said he did not know exactly, but that “they’re not where they should be.” When queried further, he elaborated: “I think that my … ideal situation would be if I walked into a room full of politicians [and] the first thing that goes through my head shouldn’t be, oh my God, there’s a lot of white men here.” By his proposed test, we’re currently failing.

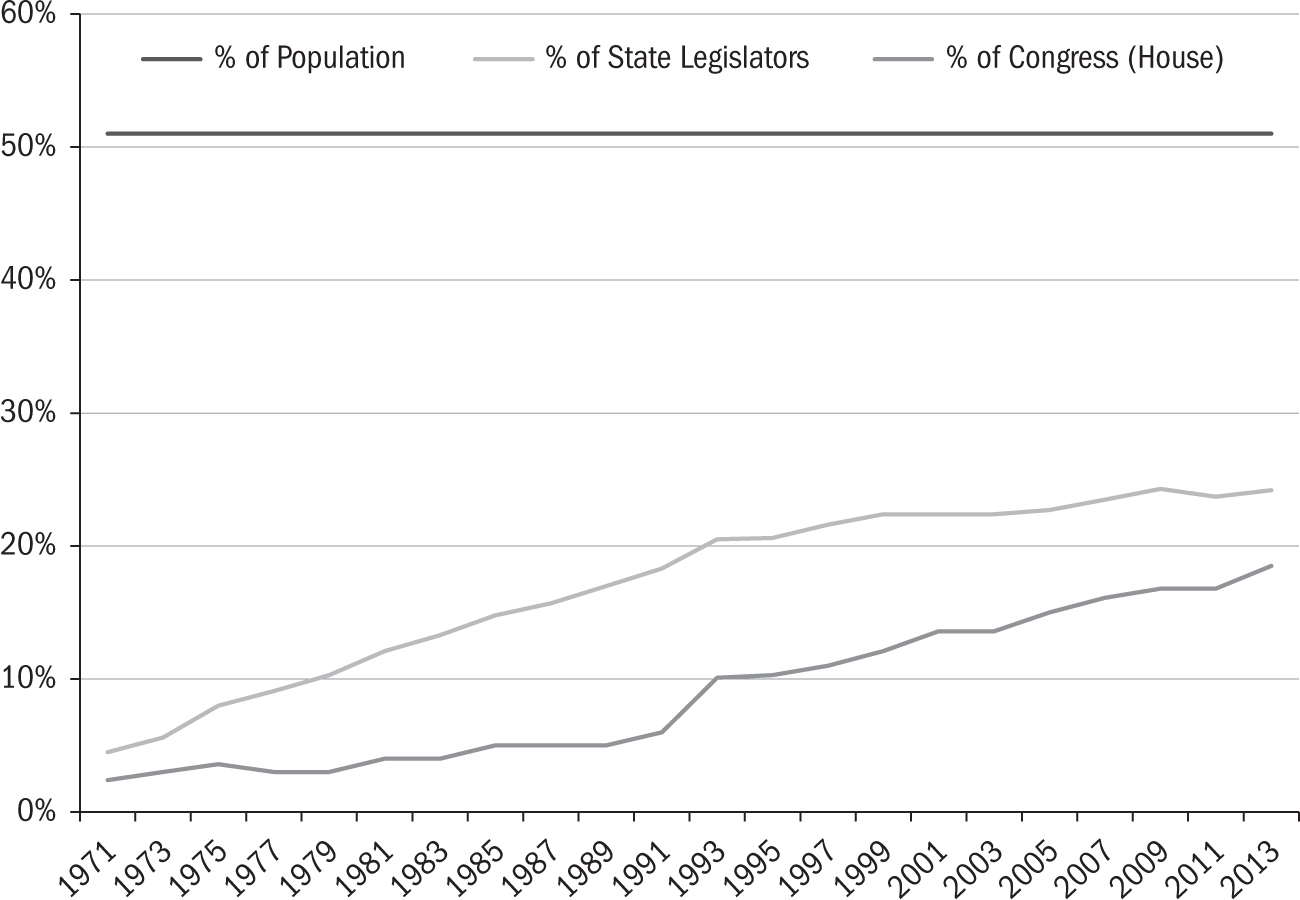

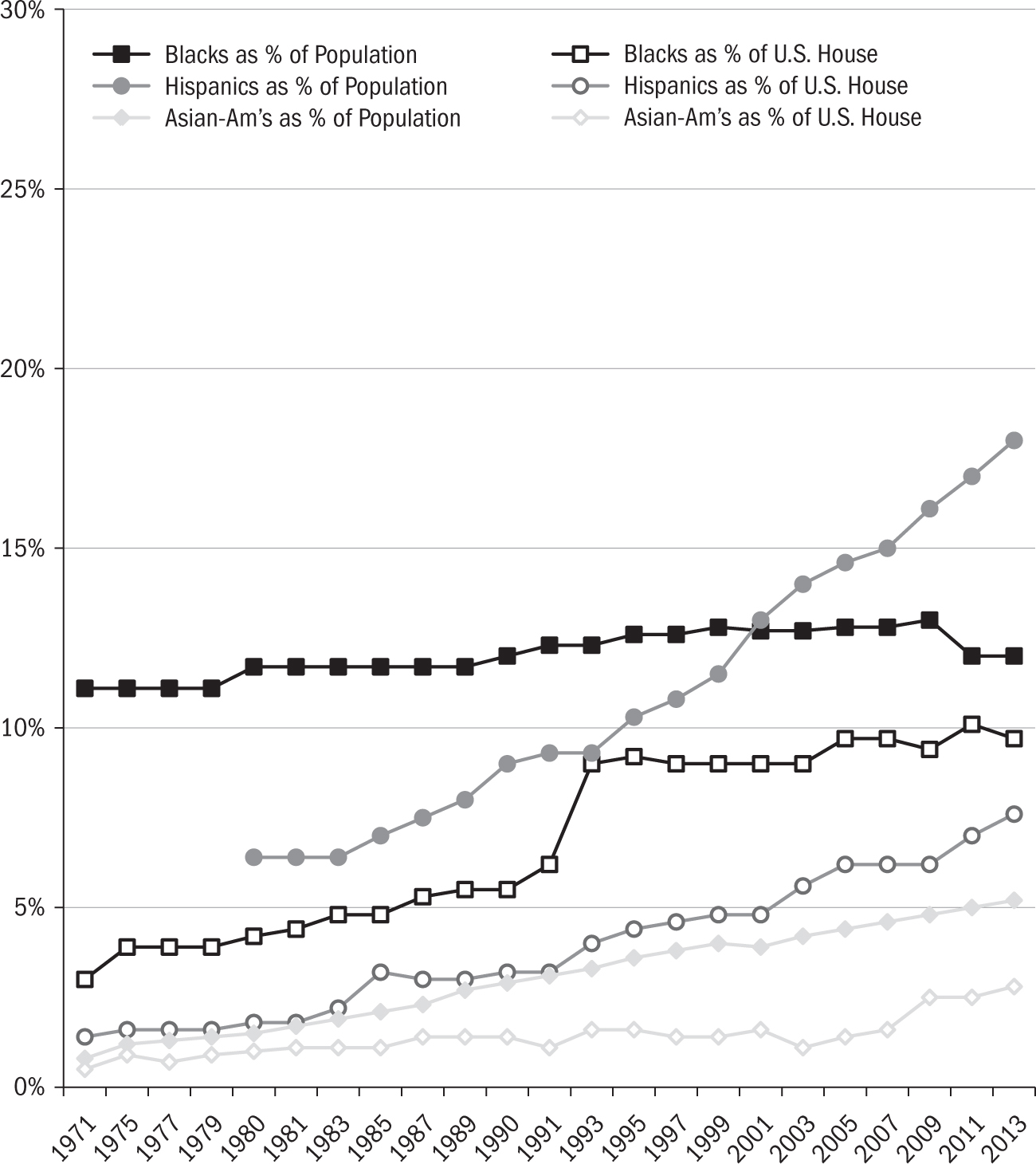

Time alone is not solving this problem of disproportionality; in the past two decades, gains for both women and racial/ethnic minorities have been at best incremental and have sometimes reversed course.29 Figures 2.1 and 2.2 depict the levels of women and minorities in Congress and state legislatures, and minorities in Congress and state legislatures, respectively. In nearly twenty years, blacks have increased their proportion in the U.S. House by about two percentage points, from 7 to 9 percent.30 Black, Asian American, and Hispanic members of Congress come almost exclusively from majority–minority districts, where racial minorities make up a majority of the population. However, these districts may decrease in number in the future as a result of the recent Supreme Court ruling in connection with the Voting Rights Act (Shelby County v. Holder).

In the same twenty-year period, women have increased their share of state legislative seats by only four points (from 21 percent in 1994 to nearly 25 percent now).31 In 2010, for the first time since women began running for public office in their own right in significant numbers, women lost rather than gained ground in Congress, and that year also saw the largest drop of women in state legislatures.32

State legislative term limits—which feminists, political reformers, and scholars of politics used to think would increase the diversity of legislative bodies—seem to have had the opposite effect, at least for women.33 As elected women are term-limited out of office, other qualified women are not coming forward to take their place, causing a decrease rather than an increase in elected women overall.34 This led political scientists Jennifer Lawless and Richard Fox in 2005 to conclude that the problem of under-representation of women is one of willingness or ability to run.35 I too find that the political ambition of women is lower than that of similarly situated men but emphasize the rationality of women’s lower ambition, in contrast to some less-rational explanations.36

Figure 2.1. Women as a Proportion of U.S. Legislative Bodies and U.S. Population, 1971–2013. Source: Compiled from data given in CAWP 2016, U.S. Census 2014, Congressional Research Service 2014a.

Few studies have investigated race and political ambition until recently. Works by Marschall, Ruhil, and Shah suggest that black candidates are more likely to run in places where blacks have previously held political power.37 Similarly, another study of minority groups beyond blacks found that minority candidates were more likely to run when their racial/ethnic group held a larger share of the population in that area.38 Relatedly, other studies suggest that that a lack of “political empowerment,” usually defined as blacks’ holding positions of power like a mayoralty, may be at least partially responsible for lowered political ambition among black citizens in those areas.39 Putting the two perspectives together might suggest that such a lack of empowerment could be a negative feedback cycle, leading to fewer candidates of color. People of color, in other words, are quite understandably more likely to run where they think they have a chance of winning. Their perceptions of their chances appear to depend on both the history of elected leadership at that level or in that area and on the concentration of their racial/ethnic group in the population. In this case, gender and race are not alike, because of geographical residential segregation by race but not by gender.40

Figure 2.2. Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans as a Proportion of U.S. Legislative Bodies and U.S. Population, 1971–2013. Sources: Compiled from data given in: Biographical Directory of the United States Congress 2014; Congressional Research Service 2014a, 2013, 2012; U.S. Census Bureau 2010, 2002, and 2001; and NCSL 2009. Note: “Hispanic” was not a U.S. Census designation until late in the planning for the 1970 census, and the question was asked only on the long form, sent to 5 percent of households. Also, the 1970 questions asked were confusing, and the resulting data inconsistent (see Haub 2012). Reliable statistics on this category are not available until the 1980 datasets.

In the general population, socioeconomic status is likely the most important predictor of who will be deterred by structural barriers, particularly given the necessity of campaign fundraising. In an era of what Nick Carnes calls “white-collar government,” the most severe under-representation in our representative government may be by class rather than by race or gender.41 Even those I spoke with in interviews, who were generally quite privileged in many ways, still seemed to think politics was for richer, more powerful people; we can only imagine how removed from politics the truly poor must feel. Future research could usefully examine what kind of candidate-deterrence effects might exist for different socioeconomic strata.

In this work, however, my goal was to minimize class differences. We already know that socioeconomic status is one of the most critical factors affecting any form of political participation.42 This project therefore attempted to study the differences in political ambition between men and women, and between whites, blacks, Hispanics, and Asian Americas, separated (as much as possible) from class. This is easier said than done, though the pre-screening by admissions committees to which I previously referred was especially helpful. Even if a student at Harvard Law grew up in a Los Angeles ghetto (as did one of my interviewees), the very fact of the Harvard Law degree will go a long way toward leveling the playing field when he or she leaves school.

We would expect at least some of the race and gender differences that show up among the larger U.S. population, and which are tied to income and education, to be minimized among these students of elite law and policy schools. Yet the research presented here tells us that gender—and some race—differences persist among even those with relatively high levels of income and education.43 In particular, my survey and interview data suggest that women, and especially women of color, are far more likely than their male counterparts to perceive the barriers to electoral office as insurmountable or as not worth surmounting, even when socioeconomic differences are minimized. For female potential candidates, the costs just seem higher, and sometimes the rewards lower.

Unrepresentative Democracy: Why We Should Care

Leadership is by nature unequal; it is an elite pursuit. In many ways, we should expect people in leadership positions to resemble one another more closely than they resemble ordinary members of the community. Why should we be concerned that a group of leaders is homogeneous in a gendered and raced way, if we are not concerned that leaders are also homogeneous in terms of personal characteristics (intelligence, ambition, aggression, charm, organizational skills, and dedication to a group or cause)?

The answer takes us beyond the personal characteristics of leadership into the function of a leader.44 Having leaders who are disproportionately dedicated, charismatic, and ambitious is not particularly concerning philosophically, as this is the purpose of a leader—to show dedication to his or her group or cause, to attract and keep members, to organize the group’s actions and affairs, to act as a public icon of the group, to ensure the care and well-being of group members. That leaders are disproportionately male and white should pose a concern, as these features do not seem necessarily related to the function of a leader but instead appear tied to historical and cultural prejudices and constraints about who is allowed to demonstrate ambition, intelligence, public responsibility, and aggression. As political theorist Will Kymlicka notes with regard to gender, which we should also apply to race, “almost all important roles and positions have been structured in gender-biased ways.”45

Following several works by political theorist Jane Mansbridge, under-representation is appropriate in a democracy only when the perspectives and interests of the under-represented group are well represented by others in situations where diverse perspectives are needed and interests conflict.46 Severe and continuing under-representation is thus just only if the axes of unequal representation are irrelevant to the interests of members of the under-represented group. This is the case with neither race nor gender.47 Lawless and Fox explain, “A central criterion in evaluating the health of a democracy is the degree to which all citizens—men and women—are encouraged and willing to engage the political system and run for public office.”48

To be clear, justice within the context of representative democracy does not demand full, unchanging equality among all groups. That inequalities exist between groups is not in itself a problem; that these inequalities affect the representation of the groups’ perspectives and interests, that the inequalities persist rather than rotate, and that the inequalities derive from a history of state action—as is the case with both race and gender inequalities—makes these significant and a matter of justice for the democratic state to address.49

Beyond the question of the intrinsic justice of more equal distributions of offices, there are also instrumental questions of policy output and governance process to consider. Both theory and empirical evidence suggest a link between substantive representation of issues and descriptive representation of people. There are good reasons why “blacks should represent blacks and women represent women,” in Mansbridge’s words. She explains that in certain contexts, and often for some good reasons, “[D]isadvantaged groups may want to be represented by ‘descriptive representatives,’ that is, individuals who in their own backgrounds mirror some of the more frequent experiences and outward manifestations of belonging to the group.”50

On the policy side, many studies support the conclusion that policy results change when legislatures become more representative by race and gender, although party and ideology complicate the effects.51 On the process side, several studies find that the inclusion of women and people of color changes the style as well as the substance of legislative decision making.52 In addition to the concerns about justice and political equality as ends in themselves, then, lack of gender and racial diversity among the elected leaders in a representative democracy seems to carry implications for interests and self-understandings of its citizens and the process and results of the political system as a whole. It is therefore alarming, from a democratic standpoint, that there seem to be some serious gaps in individuals’ willingness to run for office by key and politically relevant identity categories, including race and gender.53

What We Know about Why Gaps Persist

Considerable scholarly attention has given us important, insightful hypotheses about the motivations prompting certain people to run for office. Until the mid-1990s, however, this “political ambition” or “candidate emergence/recruitment” research studied only people who had already run (such as elected officials or candidates who ran but lost) or those who were actively deciding.54 A recent wave of research examines the political ambition of people who would make good candidates but most likely won’t run. In particular, several projects examine how such political ambition varies along identity lines.55

Why are white women and people of color less likely to run for office than white men? Existing literature has addressed this question better for gender than for race, pinpointing several important mechanisms that contribute to the continuation of male dominance of U.S. politics. Some studies, however, also provide insight into the racial issues at play, sometimes tying race to socioeconomic status and sometimes examining it from a social-psychological perspective for its symbolic motivating or de-motivating power. For both race and gender, existing explanations address structural, institutional, and individual-level factors.

First and foremost, on the structural side of the gender question, many have noted the primacy of women’s disproportionate work–family conflict as compared with men, which keeps far more women than men away from time-intensive jobs, including politics.56 At the same time, because of a persistent wage gap and the concentration of women in lower-prestige and lower-paying jobs, women tend to have lower incomes than men. They therefore collect fewer of the resources that stimulate political interest and participation.57 Women of color, who are disproportionately lower-income compared with their white female counterparts, are particularly vulnerable to the effects of both of these structural factors, which may in large part account for their paucity as candidates. A third structural barrier is incumbency, because incumbents overwhelmingly win reelection and the vast majority are male.58 (As Laura Liswood, founder and secretary general of the Council of Women World Leaders, frequently says, “I don’t believe there is a glass ceiling; I think it is just a thick layer of men.”) Finally, the structure and functioning of U.S. political parties may limit entry for political outsiders of various stripes, including women.59

Some of these structural factors, however, may be changing. Researchers used to attribute the relative dearth of women as candidates to the fact that women did not acquire as much education, as measured by college degrees. Also, men used to greatly outnumber women among graduates from law school. Both of these factors have changed in the past few decades. Women now are more likely than men to graduate from college, and law school cohorts are increasingly gender-balanced or close to it.60 Although there is no one degree for becoming a politician, a JD comes closest; lawyers make up a larger proportion of Congress and state legislatures than any other profession.61 The gender gaps in salary62 and wealth63 persist but are attenuated for elite women, who are more like elite men than they are like their lower-income female counterparts. The same could be argued of well-educated, wealthier minorities when compared with their lower-income counterparts.

Moving to more specific institutional factors, scholars have pointed to several that seem to affect the political behavior of both legislators and citizens in ways connected to race and gender.64 For example, when women (non–race-specific) hold greater power within a political institution or are seen as prominent in that institution or are visible as high-level candidates, this power and visibility may stimulate greater interest, participation, and/or efficacy on the part of other women.65 Some research also suggests the same pattern among blacks (non–gender-specific), where black citizens are “empowered” to participate politically by seeing black leaders.66

We can imagine several possible mechanisms connecting the presence or absence of members of one’s group in positions of power to one’s own likelihood of participation, feelings of efficacy, or political interest. Seeing members of one’s group may have a role-modeling effect (“I could be like her/him”). Alternately, or in addition, it could act as a powerful signal of acceptance by the institution (“Look, s/he made it”); this may have been part of the dynamic in the nomination and subsequent election of Barack Obama as president. Relatedly, but not identically, the presence of women or people of color in an institution may lead outsiders to see the institution itself differently (“Perhaps it isn’t as sexist/racist an environment as I thought”).67

With some notable exceptions, most of the key writings on how institutions affect eligibles’ political ambition are in the comparative field of political science rather than American politics research. Those who study women’s political participation and ambition in countries like those in Europe and Latin America have focused on institutional constraints and opportunities.68 Much of the recent comparative literature about women’s ascent in politics concerns gender quotas, which occur in some form (mostly as reserved legislative seats or as party-based quotas) in more than one hundred countries worldwide.69 Another major strand of research in the comparative literature investigates party-based recruitment into candidacies.70 Studies in both veins assume strong and relatively centralized political parties that have a good deal of control over choosing their candidates. These studies are thus able to fairly effectively assign blame for women’s continuing under-representation.71

In U.S. politics, where individual eligibles generally shoulder the burden of self-recruitment, the political science literature dealing with parliamentary systems—mostly institutionalist in style—is not as relevant to help us understand political ambition. Prominent recent studies about why more eligible women do not run for office in the United States have disagreed about whether to emphasize individual initiative or institutional factors.72 Here, I follow the lead of the emerging “contextual” model of political ambition, drawing from both the institutionalist and individualist literature.73 Individualized political ambition, I suggest, in line with this emerging model, depends deeply on eligibles’ perceptions of the institutional costs and rewards involved. In a U.S. context where individual political ambition is vital, we must be aware of the components of individual decision making about what politics is and whether to participate in it—but we must also acknowledge that such individual decisions are deeply informed by perceptions of the institutional barriers and opportunities one will face.

Moving from the research on structures and institutions to individual-level factors and political ambition, recent studies have identified a major gender-based confidence gap, with women generally being much less likely than men to think of themselves as qualified to hold public office.74 There is also powerful evidence of gender-role socialization effects. In contrast to men, women are socialized from infancy to believe they should prefer the private to the public sphere—or at least be able to participate fully in both, which in practice tends to reduce the time available to women for public leadership, relative to men.75 Women see few women in office and therefore may believe, consciously or not, that politics is not for them.76 Other studies have found that, as a group, women are more risk-averse than men, and in political campaigns women attach greater importance than men do to winning the race.77 Finally, a group of studies finds that women continue to be treated differently from men as candidates, particularly in media coverage but also in recruitment and treatment by party leaders, biases that eligible female candidates anticipate with distaste.78

Eligible candidates who feel different from the political “norm” may expect that their qualifications will not be seen as enough for them to win an election or do the job. They may also feel that they will have to work harder than a white male to get elected or once in office. Indeed, studies find that women candidates and legislators do work harder than their male counterparts to raise the same amount of money79 and that, as legislators, they bring home more pork to their districts.80 Last, expectations about the usefulness of politics to solve problems or create positive change may be crucially related to the reasons women and people of color do not seek elective office. We know from research that women’s primary motivation in running for office is to affect policy and “create change.”81 Yet this factor has not been examined or tested enough as a crucial component of individual political ambition among eligible candidates82—and an explanation for how and why women’s desire for office may differ from men’s.

Overall, differential expectations (about bias, barriers, disproportionate work, and the usefulness of politics) between women and men, and/or between whites and people of color, could help us explain why white men continue to be the most likely to seek political office. Understanding such expectations is critical to solving the problem of under-representation for two reasons. First, removing structural barriers alone may not be enough to create greater equality in elective offices if political-psychological challenges persist. And second, large structural factors are unlikely to change overnight.83 Even if structural barriers persist, it may be that changing the expectations held by women and people of color could convince more of them to run. In a costs-rewards framework, it is crucial to know what costs good potential candidates anticipate—but beyond this, as costs may be difficult to change, we also need to know what rewards they do or do not see.