6

Inefficient and Unappealing Politics

Women and Candidate Deterrence

You do begin to at least understand why more women [than men] would look at [running] with clear eyes and say “No, thank you.”

—Liz, MPP candidate, Harvard’s Kennedy School

Liz was a white female Kennedy School student who had experience working with government and had been working with some friends on a startup project to create a smartphone app to help people vote. It is fair to say that she was a political creature. But she was also deeply introverted and said she couldn’t stand the idea of being scrutinized and judged the way she thought she would be as a political candidate. And, she said, it would be worse for women. They wouldn’t get a fair shot at the game.

Liz’s idea of looking at the decision to run or not with “clear eyes” fits in well with this book’s overall theme of rational decision making. Rational, in the sense of comparing costs with benefits, can still take into account the “relationally embedded” kind of decision making about which Carroll and Sanbonmatsu write. Their work finds, as I do, that both costs and rewards matter greatly as someone considers running for office. For women especially, they argue, a simple lack of costs is not enough; increased political representation “is produced by both the absence of impediments and the presence of encouragement and support.”1 Costs matter, but so too do rewards.

Interestingly, as this chapter will show, the costs-benefits comparison looks different for women on the whole from the way it does for men. In particular, women—even in this sample of well-matched elite, ambitious young people—were more likely to see high costs and low rewards. The bulk of the sample had good reasons to be deterred from running, in other words, but women on the whole ended up having more good reasons not to do so. And when we look more closely at those factors enumerated in earlier chapters, and especially campaign finance and privacy, we see that women seem to feel the costs more keenly. This can show up in the quantitative data even if everyone perceives a cost, if women were more likely than men to say that they “strongly agree” with a question rather than simply “agree.” They are also significantly less likely than men to see holding political office as useful, in the sense of solving problems they think important, a key predictor of political ambition, as we saw previously.2 As Taylor Woods-Gauthier, at the time an executive director of a state-level women’s candidate-training program, explained to me in 2013, “Women just have a harder time seeing politics as an efficient means to their ends.”

Women are also strongly likely to see additional costs relating to their gender, in the form of expectations of gender biases on the part of various political actors (voters, media, party leaders, and funders). This seems related to the gender gap in feeling qualified to run, which turned up both in my sample and in earlier research.3 Given the expectations about double standards and other gender biases, however, I interpret the gender gap in “feeling qualified” somewhat differently from the way other researchers do; it is perfectly logical for women to discount their qualifications if they think they will be subjected to a double standard (as in, judged more harshly because they are female). Finally, as in prior studies, women in my sample are far less likely than men to have been asked to run, another factor strongly predicting political ambition.4 This, though, could be correlation rather than causation; if one is not already active in politics, one will be less often recruited to run. Likely, all of these processes are at least partially connected, if not strongly interlinked.

Multiple expectations and experiences on the part of women result in differing perceptions of the costs and benefits of running compared with those of similarly situated men. We end up with measurably different levels of political ambition across gender even when all in the sample are ambitious, well-educated, and studying in the schools that send people into politics. This chapter suggests that, while most in the sample are rationally deterred from running, women are more deterred than men.

Equal Ambition but Unequal Political Ambition

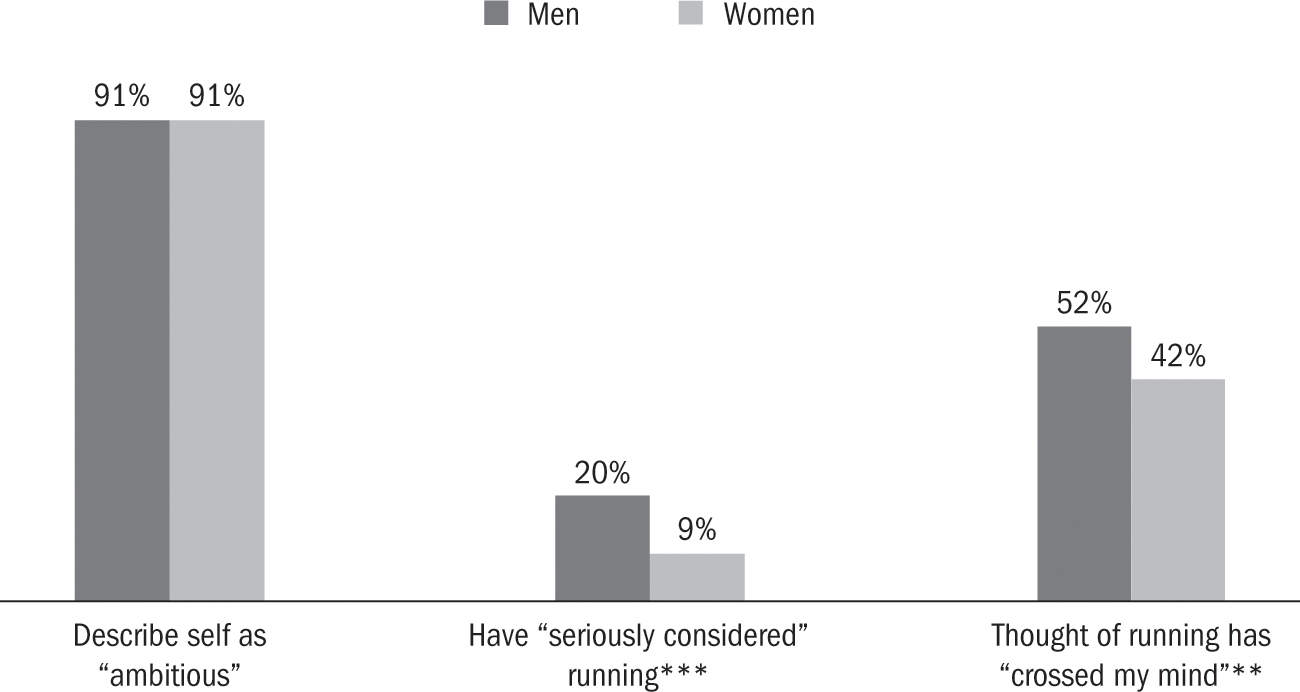

Respondents did not differ by sex in their level of ambition overall. As we would expect in this elite sample, nearly all respondents described themselves as “ambitious.” There are no significant differences in describing oneself as ambitious across sex, nonwhite race,5 or graduate school/program. As figure 6.1 shows, ninety-one percent of women in the survey sample, and the exact same percentage of men, agreed that the term ambitious described them well or very well. There was no sex difference, either, in the proportions of men versus women calling themselves “very ambitious” instead of merely “ambitious”; 49.3 percent of the men6 and 50.0 percent of the women chose the “very” category.

However, not all respondents were equally politically ambitious. When asked if they had ever thought about running for public office (not including student government), significantly more men than women answered in the affirmative. Men were much more likely than women to say both that they had “seriously considered” running and that the thought had “crossed their mind.”7

Only about half of all women had thought about running in either way (fleetingly or seriously), while nearly three-quarters of the men had done so. Looking at who had thought seriously about it, we see that 20.3 percent of men but 9.2 percent of women had done so. To look at it another way, of those who had seriously considered running for office, fewer than a third were women.8

Figure 6.1. Ambition and Political Ambition, by Sex. Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. * p < .1, ** p < .05, *** p < .01 (for difference between sexes). N = 716 (ambitious Q). N = 753 (thought of running Qs).

The figure sets up an intriguing and important question. Why, in a sample of highly ambitious women and men, are the women significantly less politically ambitious than the men? The men and women in this elite sample should be, and in many ways are, more alike than they are different. The work of the highly selective admissions committees at these schools served to ensure a sample matched on all kinds of characteristics that tend to have a gender skew in the general population, such as ambition, family income, and education. In my survey sample, there is no gender skew to these characteristics among respondents. Also, one of the biggest differences between adult men and women—time spent engaged in child care—is mostly absent among my sample, as few of my respondents had children.

Yet even after we control for family responsibilities, general ambition, education, and income, there is still a large difference in the political ambition levels of the men and women in my sample, as shown in the illustrations earlier. One interpretation is that these differences could be tied in some way to biology (perhaps women are just genetically averse to politics?). However, the data that respondents gave about their previous political activities contradict such an interpretation. More female than male respondents said they had been active in student government in high school (although there is debate about whether this bears any relation to running for office later in life).9 And there is no difference by sex in reports of participating in politics outside of school while in high school. If anything, the women report having been more active in politics in high school and report about the same level of activity relating to politics in college. Some research has found that girls in general are differently socialized in families as far as politics is concerned.10 But among the ambitious and elite group of my sample, men were not more likely to have been politically socialized than women (in the sense of discussing politics with their families while growing up),11 and the women were just as likely to have run for school office in high school or college.12

Significant sex differences do not begin to emerge until respondents’ recent reports of political activity, in the past two years (in college or immediate postcollege). Something seems to happen to young women that changes their perceptions of the relative costs and rewards of politics, and the change, as far as I can tell from these data, comes between high school and college or in college. As I did not expect to find this, I do not have sufficient measures on this point in my study, either in the interviews or the survey data—future research is needed to evaluate this seemingly critical political development phase in a gender-conscious way. For now, I will stick to my data and tell you what I know for sure: the young men and women I surveyed and interviewed, by the time I got to them, saw the political world differently from each other.

In terms of women’s lower political ambition when compared with those of men, research has suggested various answers, including that women lack confidence,13 that women see bias in politics,14 that women are more strategic about how and where they spend their time,15 that women are less likely to be asked to run (recruited),16 that the prospect of electoral competition itself is more offputting to women than to men,17 and that women are more risk-averse.18 I find support in my data for all of these explanations and can also add a new consideration: in addition to seeing more and higher costs (to put into my cost-benefits framework what research has found), I also find that women see fewer rewards in the idea of candidacy. Not only do the costs seem higher when compared with those of similarly situated men, in other words, but the benefits seem lower.19 That, I argue, is a crucial and missing piece of our explanation of women’s political ambition. In this chapter, I walk through the data on both the costs and the rewards sides, now looking at women and men separately.

Women’s Greater Sensitivity to the Costs of Running

Previous chapters suggested that young and elite prospective candidates perceive multiple costs to running for office, such as the need to raise large sums of money and the perception of privacy invasion by media or opposition research. These costs were perceived by large proportions of the sample and seemed to deter those who did not see corresponding rewards to balance out these costs. Men as well as women perceived and were deterred by these barriers—but as the data in this section will show, women were more deterred than men.

If we return to table 3.4, giving survey data on the costs of running, we can now look at whether women and men perceive and react to these costs similarly or differently. Table 6.1 replicates that first table, but now for each cost I give the means for women and men separately, as well as an indication of whether the difference is statistically significant. For many variables, there is no significant difference between men and women. But a few do show differences; for example, men in general perceived invasion of family’s privacy, losing at anything, and having skeletons in their closet to be more costly. On the other hand, women were more likely to perceive as costly things like dealing with the media, facing hostile questions, needing a thick skin, and taking risks.

The final row in table 6.1 gives the average scores of men versus women on the overall costs index developed in the previous chapter. This gives us a sense of how the costs stack up for women versus men as groups and tells us that on the whole, even before we add in any new costs, women overall perceive running as more costly than men do. The difference in means is not huge, but it is strongly statistically significant.20

When I run regression analyses looking at the factors that affect political ambition, as shown in table 6.2, the coefficient on the costs index is strongly significant, despite the inclusion of multiple controls, including respondent sex. And when I use the costs index itself as a dependent variable, as shown in the second column, the coefficient on being female rather than male, while not large, is strongly statistically significant. In other words, costs matter collectively for political ambition, and women see more of them in general than men do.21

Women See Lower Rewards

Separately from the analysis of costs, we can look at whether perceptions of the potential benefits of running for or holding political office differ by sex. As one might expect, there is indeed a difference; women see fewer of the possible rewards and are sometimes less enthused about those they do see. If we look again at the possible individual rewards variables that went into that “rewards index” in chapter 5 and look at means for men versus women, as in table 6.3, some clear differences jump out.

TABLE 6.1. Costs Variable Means and Overall Index, by Sex (with Each Cost Cariable Constrained to a Binary) |

||

Perceived Cost |

Mean for Men (percent) |

Mean for Women (percent) |

It is important to me that I can “[Be] sure of always having a relatively well-paying job” |

87.1* |

89.9 |

I would be more likely to run if “It would not interfere with [my] family’s privacy” |

81.1** |

75.3 |

I would be more likely to run if “Campaigns were fully publicly financed, so [I] would not have to raise money for [my] campaign” |

78.0 |

77.5 |

I would feel negative about “Calling people to ask for donations” |

72.1 |

75.2 |

I “Hate to lose at anything” |

71.2*** |

56.0 |

I “Avoid conflict whenever possible” |

51.3 |

47.0 |

The consideration of being expected to contribute financially to my family of origin is “very or somewhat important to [my] choice of future job(s)” |

44.0 |

49.1 |

I “will be expected to contribute financially to [my] parents, siblings, or other relatives in the future” to a large or moderate extent |

43.4 |

48.7 |

I would feel negative about “Dealing with the media” |

31.2*** |

46.5 |

I would feel negative about “Facing hostile questions” |

24.8*** |

50.1 |

I am not “Thick-skinned” and I believe “It takes a thick skin to survive in politics” |

26.8*** |

47.6 |

“In today’s media environment, you’d have to be crazy to run for office” |

33.7 |

40.1 |

I would feel negative about “Dealing with party officials” |

34.5 |

32.3 |

I am not “Willing to take risks” |

27.9*** |

37.6 |

I believe that politicians often “lie” |

28.4 |

29.3 |

I do not fit into either major political party |

30.6 |

26.2 |

I would feel negative about “Going door-to-door to meet constituents” |

26.7 |

29.3 |

I would feel negative about “Making public speeches” |

12.4*** |

24.6 |

I think politicians often “Act immorally” |

15.8 |

13.5 |

I would be more likely to run if “[I] had fewer skeletons in [my] closet” |

13.9** |

8.2 |

Overall Costs Index Score |

.318*** |

.355 |

Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample; N = 764 |

||

TABLE 6.2. Regressions with Costs Index Predicting Political Ambition, and Other Factors Predicting Costs |

||

Model 1 (Logistic) |

Model 2 (OLS) |

|

Dependent Variable: Had thought seriously of running for office (binary) |

Dependent Variable: Costs Index (continuous) |

|

Independent Variables/Controls |

||

Female |

−.898*** |

0.034*** |

Nonwhite |

.311 |

0.012 |

In public policy program (versus law) |

.194 |

−.023* |

At either Harvard School (versus Suffolk) |

.397 |

0.011 |

Family income at about age 16 |

−.041 |

−.004 |

COSTS INDEX |

−4.188*** |

— |

Constant |

−.338 |

.330*** |

N |

748 |

758 |

R-Sq |

.07 |

.12 |

Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample; N = 764 |

||

As before, with costs, this is not a story purely about gender difference; there are several questions on which men and women as groups did not disagree much, or at all. But there are also some rewards to running that men as a group saw far more than women did, such as thinking that politics solves problems. To put it another way, if we look only at those people who agreed strongly with the statement “The problems I most care about can be solved through politics” and break down those strong-agreers by sex, the group is 80 percent male.22 On the other side, if we look only at those who disagreed with that statement, the disagreers group is 57 percent female.23 Those two groups, however, may overstate the case, as they are only those who feel most strongly. What about those who agreed or disagreed, but not strongly? The same gendered pattern shows up, although less starkly; women, even though they are exactly half of the sample as a whole, are less than a majority of those who think that politics solves important problems, and a majority of those thinking it does not.24

TABLE 6.3. Rewards Variable Means and Overall Index, by Sex |

||

Perceived Reward |

Mean for Men (percent) |

Mean for Women (percent) |

Considers self “Good at being in charge” |

86.5 |

88.5 |

Would feel positively about “Being a part of history” as a candidate^ |

85.6 |

84.3 |

Considers “Feeling useful, doing something good in the world” an important life goal^ |

73.1 |

87.8 |

Considers self “A good public speaker” |

80.8*** |

69.2 |

Would be more likely to run if “Cared about an issue and knew [I] could make a difference if [I were] in office” |

56.3 |

61.7 |

Would feel positively about “Going door-to-door to meet constituents” |

56.7 |

52.1 |

Would be more likely to run if thought “Could help [my] community” |

52.1 |

53.4 |

Would be more likely to run if thought “It would help [me] get a better job later”^ |

47.4 |

44.2 |

Thinks “The problems I most care about can be solved through politics” |

48.5*** |

30.5 |

Considers self “Very competitive”^ |

59.0** |

29.9 |

Would feel positively about “Attending fundraising functions” |

27.7 |

34.0 |

Has strong opinions on policy issues |

22.6** |

28.7 |

Believes one person can “make a difference in politics” |

26.0 |

21.4 |

Thinks politicians often “work for the public good” |

25.7* |

21.7 |

Would be “very likely” to interrupt professor in a class |

26.6*** |

14.6 |

Thinks politicians often “help people with their problems” |

21.0*** |

14.2 |

Considers becoming “famous” an important life goal |

16.6*** |

8.4 |

Overall Rewards Index Score |

.370*** |

.315 |

Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample; N = 764 (for most questions) Sex Difference Significance: * p<.1, ** p<.05, *** p<.01 ^ These questions have a low n (around 47 responses each), as they were asked only in the final survey wave. |

||

The interviews and survey data both suggested in chapter 4 that believing that politics is useful to solving problems is a key reward component of running for office. The fact that young women are significantly less likely than men to believe that politics has this kind of reward potential is an important reason why women as a group perceived fewer rewards when thinking about running for office, as compared with similarly situated men. But other variables show large differences as well, including thinking that politicians “often help people with their problems,” which men believed far more than women. Men were also about twice as likely to want to be famous, to be ready to interrupt, to think themselves good at public speaking, and more likely than women to see rewards from the competition inherent to politics. On the other hand, women were somewhat more likely to have strong policy opinions. But overall, men were far more likely to see politics, and running for office, as potentially rewarding than women were.

Charlotte, a white female MPP candidate at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, mused on several of the costs at once, saying:

I’d hate [running]. Just because I think that there’s such a good chance you could lose. I’m a pretty risk-loving person, but I wouldn’t enjoy that kind of a risk … for the most part, it’s just going to be really hard to get the work done once you’re in there. And so, I mean it doesn’t pay well, it’s—you’re frustrated all of the time, you’ve got no job security ’cause you have to think about getting elected again, and running just seems miserable, having to knock on a million doors, convince people that you’re awesome and the other guy sucks, even if that’s not necessarily true, and then promising change that you probably can’t bring, because it’s not just you in office, it’s you plus like 50 other people, so, just because you’re elected doesn’t mean things are necessarily going to change, even with your best efforts. I just feel I can effect a lot more change and do good work from the outside and find it much more satisfying.

Charlotte was one of a number of what we might call “refusers”—those who absolutely disliked the idea of running, no matter how I asked about it. It wasn’t that she hadn’t thought it through. Being a student at the Kennedy School, surrounded by politicians and former politicians and future politicians, she had thought about it quite a lot. But put together, the high costs and low rewards that she perceived were pretty darn deterring.

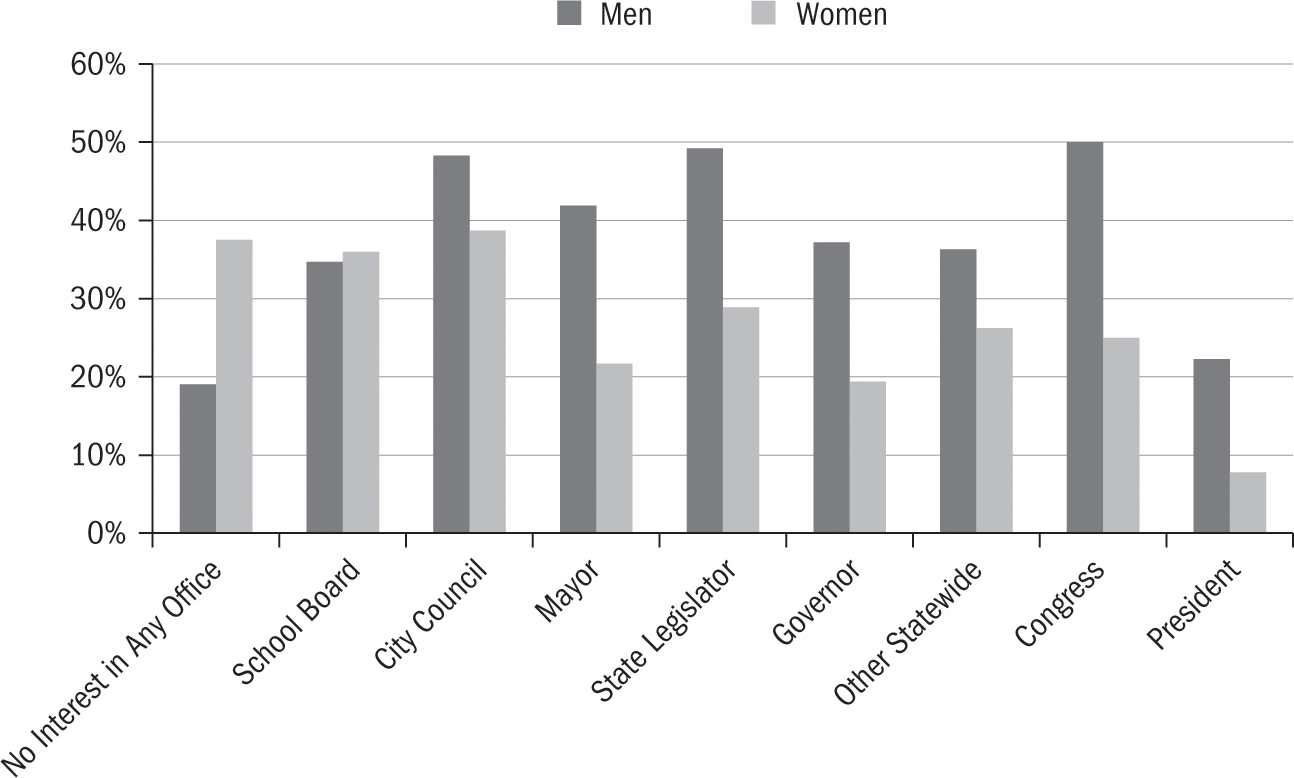

Levels of Office, by Sex

Figure 4.1 showed the proportions of all respondents in the sample who said they could imagine themselves running for different types of office at different levels of government. When we look at the sample as a whole, we see a good level of interest across multiple levels, without much of a pattern, except that the lowest number of people wanted to run for president and the highest for city council. If we now go back to that chart and break down the responses by sex, a different pattern emerges, only for women. Figure 6.2 shows the percent of men versus women who said yes, they could imagine themselves maybe running for that type or level of office at some point in the future.

Figure 6.2. Levels of Office, by Sex; N = 764

If we look only at the darker bars (men), the levels of possible interest in all offices is relatively high and pretty constant, with a dip in wanting to run for president (although more than 20 percent of men in this sample seemed ready to consider it!). And men’s level of “No interest in any office,” shown in the far-left bar, is quite low compared with women’s. Women, on the other hand, seem more interested in local legislative offices (school board and city council had the most interest) and show more interest in the legislative rather than executive options at both the state and national levels, preferring state legislator to governor and Congress to president. Indeed, a dummy variable testing for female sex was strongly and negatively associated with a variable testing for interest in higher levels of office.25 And women were far more likely than men to be in that “never want to run for anything” category, the “refusers.”26

Costs versus Rewards Distributions, by Sex

The data presented thus far suggest that for otherwise ambitious women as a group, political ambition is simply—and rationally—lower than for similarly situated men. This does not mean that women are not ambitious; they are. And it does not mean that women do not want to change the world—the interviews and survey evidence strongly suggest that they do. In fact, women were significantly more likely than men to rank “improving life in my community” as an important life goal.27 Men too wanted to change the world yet were far more likely to think that they could do so through politics. Not every man was more politically oriented than every woman, but the distributions speak to an important pattern: those who believe they could change the world through politics were far more likely to be men than women.

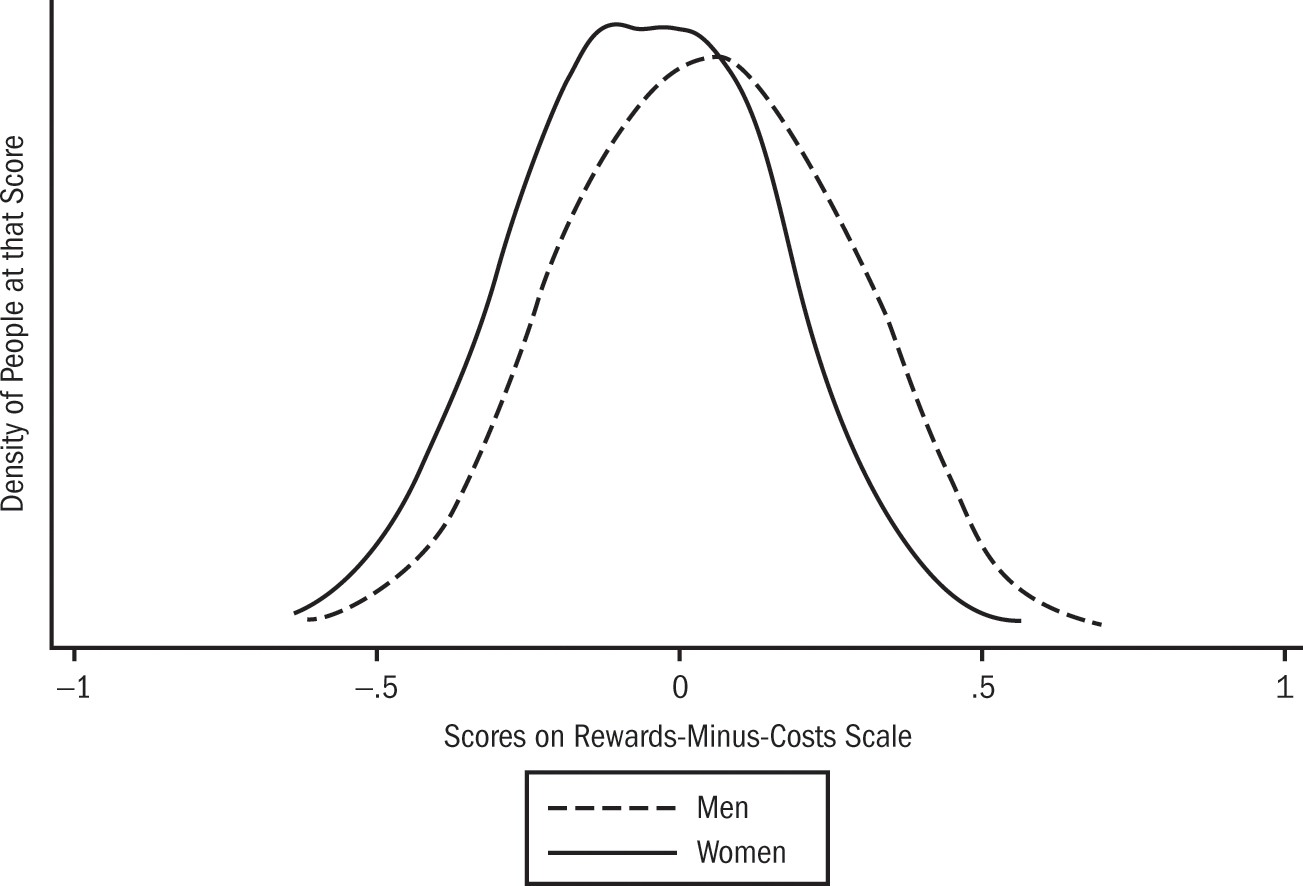

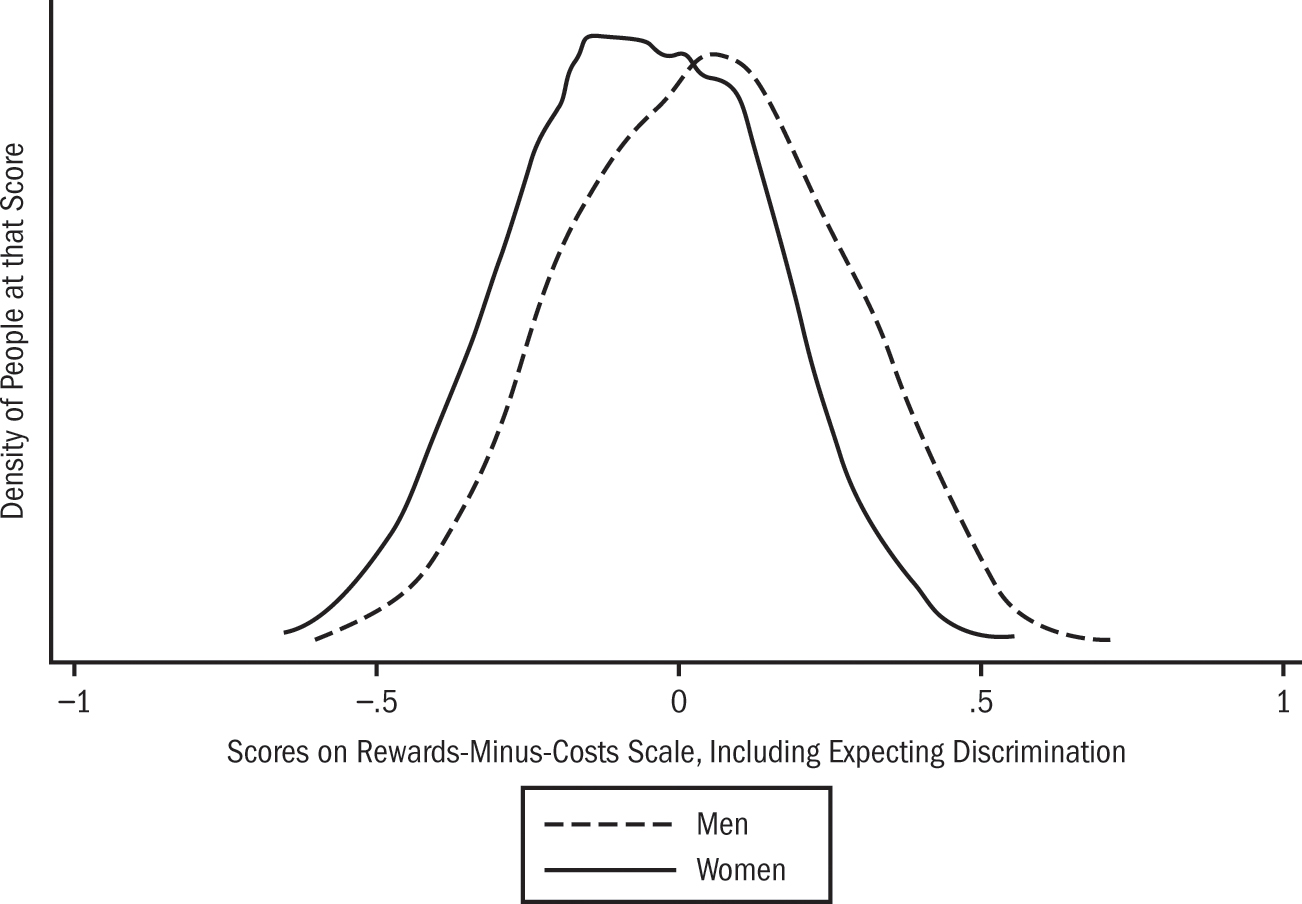

Earlier, figure 5.4 showed the distribution of rewards-minus-costs scores for the sample as a whole as one distribution curve. Now, in figure 6.3, I show the curves for men and women separately. As the figure makes clear, the curves overlap more than they diverge—women and men are more alike than they are different.28 But on the whole the men’s curve is shifted to the right of the women’s, further toward the rewards side and away from the costs side. The bulk of people, in other words, both male and female, hover around the 0-line when costs are subtracted from rewards. But in this rare activity, running for office, where it is the far-right tail that likely matters most and not the great bulk in the middle, that far-right tail (where rewards far outweigh costs) has far more men than women. Small but powerful marginal differences in the means can add up to large differences in the tails.29

Figure 6.3. Distribution Curves of Rewards-Minus-Costs Index Scores, by Sex (Kernel density estimates). Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. N = 764.

But that is not the end of the story. It turns out that in addition to seeing higher costs and lower rewards on average, women also saw a whole other important cost that affected the sexes differently: discrimination. Some people were vague about where the bias might come from, while others were quite specific, naming a variety of actors who could show bias (voters, party leaders or other gatekeepers, recruiters, funders, and journalists). Many of my interviewees seemed to agree with the famous sentiment of comedian Elayne Boosler from the 1980s, that she was “just a person trapped in a woman’s body.” Yet being so trapped, they expected to be treated like women rather than like people. And taking this factor seriously as a cost further shifts women’s scores both away from men’s and away from wanting to run.

Role Incongruity

I think it’s harder for women than it is men to run. Not only because of the way they approach problems …, but also because of the way they’re able to deliver a message, the problem is if they’re too staccato or too hysterical about it, it sounds like you want to get away from it, it sounds like an angry woman sounds. Whereas a yelling man is like, “holy crap,” and you at least acknowledge that something is going on, so it’s hard for [women].

—Ben, white male student at Suffolk Law School

In an interview long after her race, Bonnie Campbell, the former attorney general of Iowa and the Democratic Party candidate for Iowa governor in 1994, recounted the difficulty she had simply in getting dressed each morning of the campaign. If she wore pants, she said, she feared criticism for trying to imitate men. (This was before Hillary Clinton popularized the black pantsuit for political women.) But if she wore a skirt, she thought she risked looking weak to potential voters. If she wore no makeup or jewelry, she knew the media would comment on their absence, perhaps suggesting that she did not care enough about her appearance or was a lesbian. But if she wore makeup and jewelry, she feared that commentators or voters would think she had something to hide. She said, “Sometimes I would just stand in front of my closet, paralyzed.”30

Campbell doubted that her male opponent had the same problem, instead linking her experience to the difficulties women have when running for political office. She said her opponent used her sex against her in underhanded ways, including saturating the radio airwaves of the state with negative ads featuring the sounds of a lion roaring with a male announcer saying, “It’s a jungle out there.” The ads implied that the female Campbell was not tough enough to be governor (despite her years of experience as a lawyer and attorney general of the state). “Running a political campaign is often antithetical to what it means to be a woman,” she reflected several years after losing that race.31

Women seeking leadership roles, as with Campbell, often feel that being visibly different from the male norm affects them in some way. When reporters asked veteran Representative Pat Schroeder (D-CO) if she was “running as a woman” in her 1988 presidential bid, she responded, “Do I have an option?”32 Her levity in no way detracts from the power of this message. She clearly felt she would be perceived as a woman, whether or not she wanted to be, and therefore as different.

In some cases, difference can be a helpful attribute, as when “insiders” are seen as corrupt, incompetent, or even just “business as usual,” in a time when the public is fed up with such. In these cases, “outsider” status is a positive, and insiders may even attempt to emulate it.33 In general, however, and especially in cases of crisis, military conflict, or a poor economy,34 scholars of gender suggest that the gendering of leadership as masculine, and the conflation of politics with war, conflict, and/or force, all of which are historically masculine rather than feminine pursuits, presents challenges for women.35

The dilemmas detailed by Bonnie Campbell in her gubernatorial race reminiscences are described by scholars of women and leadership as “gender role incongruity.”36 While gender roles have been changing rapidly in the past few decades, the preponderance of evidence suggests they are still strong influences in most people’s lives.37 Gender identity is one of the earliest things we learn about ourselves and those around us; most children begin defining themselves and others in gendered ways at age two if not before.38

Certain features of gender roles have proven immune to the feminist challenges of the past century. As a society, we still associate masculinity with authority, leadership, and aggressiveness, while we link femininity with compassion, nurturance, and subservience and still assume women to be primary caregivers for children and the elderly.39 In a speech in 2002, U.S. Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) suggested that a woman running for office was and still is something of a gender paradox: “Think about the attributes of someone running for office—smart, tough, knowledgeable in foreign policy. And if you do have all these things, my God, are you really a woman?”40

Scholars of women and politics agree that the gendering of the public leadership as masculine creates challenges for women candidates. Susan Carroll writes, “Although socialized to exhibit values and behaviors considered appropriate for females, in running for office women enter a sphere of life dominated by masculine values and behavior patterns.”41 Georgia Duerst-Lahti and Rita Mae Kelly, in their study of gender power, say, “Our review of the literature on power and leadership reveals how rarely the words women and feminine are associated with them and how heavily men and masculinity saturate our understanding of power and leadership.”42 Likewise, Cheryl King cites a “preference for masculine” in our cultural definitions of leadership, and writes that leadership and governance “[bear] an explicit masculine identity.”43 Lyn Kathlene says bluntly, “Few social and occupational domains are more masculinized than politics.”44

One result is the necessity for women to prove they can do the job as well as the men. Political scientist Sue Thomas has written, “Women legislators often find themselves continuously in a position to prove themselves to be every bit as competent, knowledgeable, dedicated, serious, and ambitious as their male counterparts.”45 In several over-time studies of women and men who hold the same jobs, women indicate that they have to work harder. The researchers argue that “the association between sex and reported required work effort is best interpreted as reflecting stricter performance standards imposed on women, even when women and men hold the same jobs.”46 Noting the findings from experimental research showing that people rate work more highly when told it was done by a man, one researcher (Gorman) explained, “This is what women are up against. They have to prove themselves.”47 The prospect of additional hurdles to surmount because of one’s sex or race may make the idea of competing for leadership, and particularly against a white male (the vast majority of incumbent office holders48), less appetizing than it might be for another white male.

Research on gender and political ambition has found that women who have not themselves run for public office anticipate that female candidates as a group will face sexism. In a 2008 study by political scientists Jennifer Lawless and Richard Fox, fully 87 percent of women agreed that it would be “more difficult” for a woman to be elected to high-level public office compared with a man.49 “Women are nearly twice as likely as men to contend that it is more difficult for women to raise money for a political campaign, and only half as likely to believe that women and men face an equal chance of being elected to high level office (13 percent of women, compared to 24 percent of men).”50 Women in their sample (adult professionals in the fields leading to political candidacies) were far more pessimistic about the possibility of female candidates’ ability to raise as much money and gain as many votes as male candidates, and they were more skeptical than the men about their own chances of winning. Many of their female respondents connected these negative assessments to their sex.51 Lawless and Fox conclude, “The perceptual differences we identified translate into an additional hurdle women must overcome when behaving as strategic politicians and navigating the candidate emergence process.”52

The Cost of Being a Token

One additional factor, which some interviewees raised, was the idea of not wanting to enter an institution where they would be in the minority. This could certainly make sense in the sense of partisanship—individuals’ political ambition could rationally wax and wane depending on whether their party is in the majority or minority. But this kind of minority-anticipation could also play a role in terms of race, gender, or other identity factors (possibly sexual orientation, religion, or others, although my research did not examine these).

In terms of gender, research on participation (and to some extent political ambition) has found that young women are far more likely to consider politics as a possible career choice when they see women role models serving in office.53 This may be due, as other research and theory has suggested, to an expansion of the social definition of who can rule.54 But what of the related idea that women may be more likely to want to serve in office if they didn’t think they would just be the “token woman”?55 Public policy student Esther certainly talked about how much she admired the pathbreaking women currently serving in Congress. Yet her description, however laudatory, did not suggest that that kind of pathbreaker role was one she necessarily wanted for herself. She said, “There are some fabulous women leaders in Congress, but they are certainly not the majority. So it’s a brave thing for a woman to have to do, to … go down that path where not many others have, it’s hard.” Recent research suggests that where more women run, more women will run56—but that doesn’t make it any easier for the individual pathbreaker who must go first or alone.

Women in the Sample

The Millennial women in my study were, for the most part, extremely aware of their difference from the male norm in politics, and most considered it a disadvantage. In general, these women already perceived higher costs and lower rewards from running than did the men. Adding in perceptions of discrimination and double standards appears to have further weighted the scales against running for the women studied.

Charlotte, the white female MPP student quoted earlier, explained her perceptions of gender and racial bias in this way:

I think it’s a lot harder for a person of color to be elected, and I think it can be harder for a woman to be elected also. I think a white male is perceived to be genderless and colorless, so his gender and color just [don’t] enter the picture, whereas the fact that someone is a woman or a person of color, those are things to think about and so that enters the picture in a way that being a white male doesn’t. And I think it also affects your access to those resources we were talking about. I think you have a lot less access to resources when you’re a person of color or a woman.

Similarly, Liz, the public policy student quoted at the start of this chapter, gave an explanation of why more women might not want to run that begins to link (gender-related) experiences to expectations of future discrimination. She said she thought that “[w]omen are taught to be less publicly opinionated in a lot of ways, so to have to stand up and proclaim what you think on any issue under the sun all the time .…” This thought led her to another: “And ambition. You don’t get rewarded for it on lower levels, so to suddenly decide you have this burning fire, or want power, it’s less commonly found.” Women’s expectations of being treated differently were, to her mind, perfectly rational given experiences of being expected to act differently from men.

This kind of anticipation of discrimination could be seen as an additional “cost” to running that affects women far more than men. Women in general, and especially women who had already experienced discrimination, were very likely to anticipate it in the future. The result was that both men and women anticipated discrimination against women in politics, but women more so. This pattern, as it turns out, applied to many of the other costs of running that were explicated in previous chapters. While most people seemed affected by these costs, women in the sample were often more sensitive to them than the men.

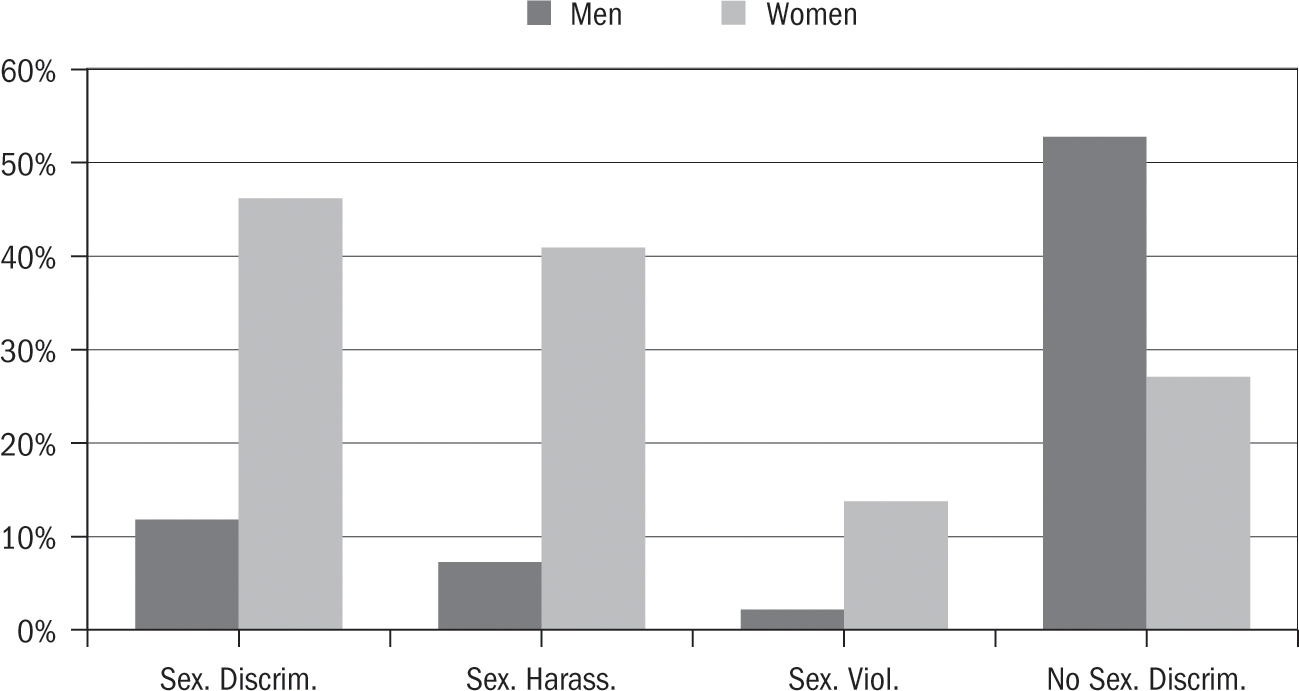

By the time they reach their mid-twenties, the mean age of the sample, men and women have had more than two decades of gender-differentiated experiences to draw upon. Most of the women and some of the men in my study appeared to have thought a great deal about gender, both in their own lives and as a concept more broadly. Many (including men) talked in interviews about having taken women’s studies or gender studies classes, or having encountered this subject matter in other classes in college. And fairly large proportions, especially of the women, had had what scholars believe to be critical gender-consciousness experiences (discrimination, harassment, or assault based on sex, gender, or sexuality).57

Women were far more likely than men to report experiences of all forms tested except religious discrimination. Nearly half of the women (46.0 percent) and 12.1 percent of the men said they had faced discrimination because of their sex. Similarly, 45.9 percent of the women and 7.3 percent of the men reported having been sexually harassed. Sexual violence was not as widespread but had still touched the lives of many in the sample: 13.3 percent of the women and 1.8 percent of the men.58 Such experiences, particularly sexual harassment and assault, are described as “gender-motivated violence” by those who study them. Such experiences can have a “consciousness-raising”59 effect, leading those who connect their experience to larger gender trends to see the “personal as political,” in the words of a famous slogan of the 1970s women’s liberation movement.60 As Simone de Beauvoir famously wrote in The Second Sex in 1949, “One is not born but rather becomes a woman.”61

Women were also far less likely to have lived a life free of experiences of discrimination. Overall, fully half of the men (52.2 percent), and 64.6 percent of white men, reported that they had never experienced discrimination in any of the listed forms. Conversely, only 28.0 percent of women (33.7 percent of white women) reported no experience of discrimination, a strongly significant difference statistically, by both race and gender.62 Figure 6.4 shows these gender differences graphically, comparing the proportions of women versus men within those saying they have experienced any of the listed forms of discrimination, and, in the final column, showing the percentage of men versus women reporting no experience of discrimination. In short, the cumulative effects of discrimination fell far harder on women in the sample than men, particularly when the discrimination was based on sex, gender, or sexual orientation/gender identity.

These experiences of discrimination strongly predict expectations of future discrimination. Respondents who had experienced discrimination, in other words, were more likely to expect that the political world was unfair. Scholars of identity, particularly relating to race, gender, and sexuality, suggest that experiences of discrimination can “teach” individuals to expect more of the same in the future.63 Causality, however, could run in another direction; it might be that those who are aware of or sensitive to discrimination are more likely to view experiences in that light. Either way, experiences of discrimination correlated strongly with expectations of it.

Figure 6.4. Experiences of Sex-Linked Discrimination, by Sex. Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. N = 764.

Large majorities in the survey sample expected that whiteness and maleness provided a professional advantage. Both men and women expected women to face bias in the working world and in the media; 67.2 percent agreed with the statement “Men get more opportunities than women for jobs that pay well, even when women are as qualified as men for the job.” Similarly, 91.8 percent of agreed that “Women are judged for their appearance more than men are.”

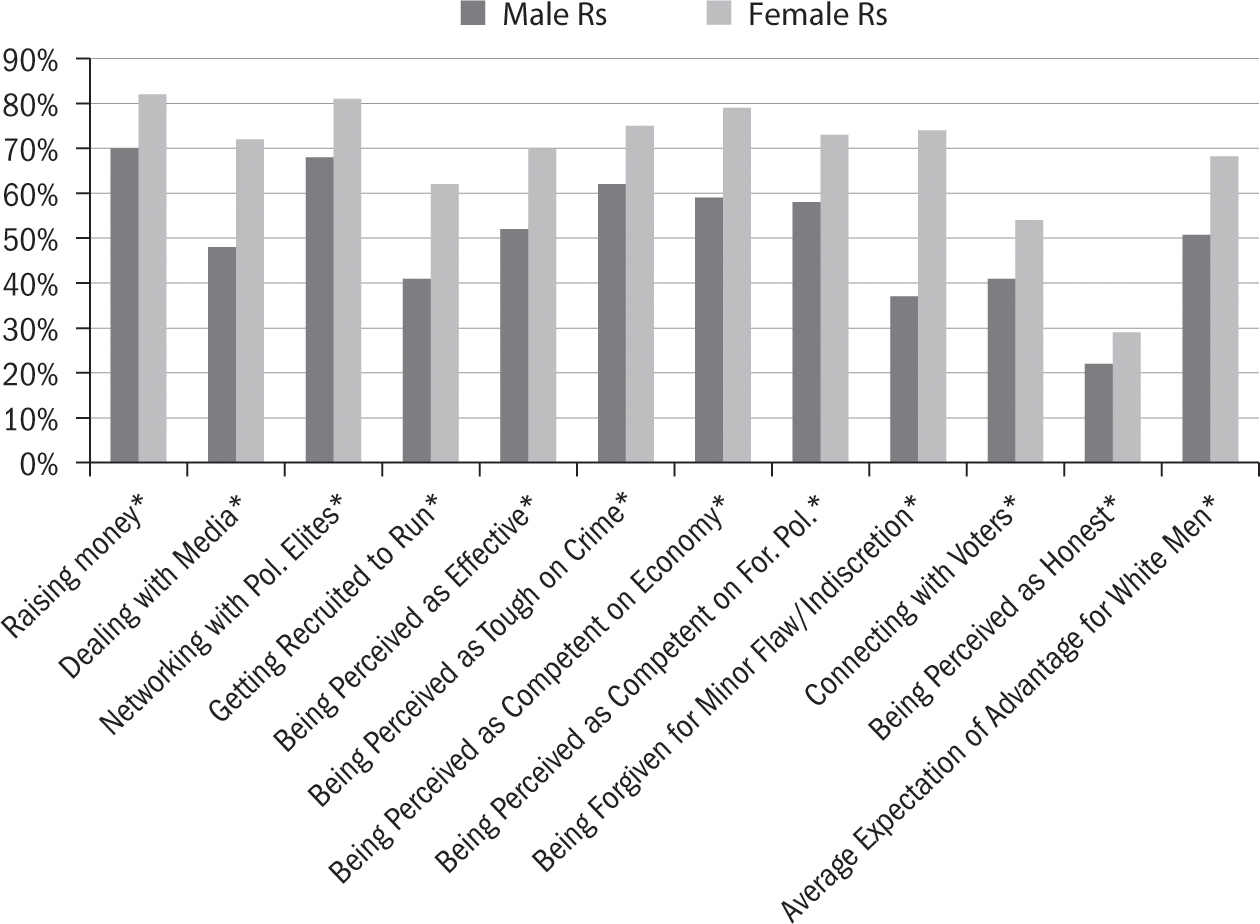

Not surprisingly, given this set of expectations about gender in the wider world, politics as a specific domain was considered strongly biased in favor of men. Only 7.4 percent of the sample agreed with the statement “It is just as easy for a woman to be elected to high-level political office as a man.”64 These kinds of “anticipation-of-discrimination effects” are shown graphically in figure 6.5, which gives average answers by respondent sex to a series of questions about who might have an advantage in campaign activities. The survey asked respondents to mark the type of candidates they thought would have an advantage in each type of campaign activity in a matrix of types of candidates by race and sex: white male, white female, black male, black female, Hispanic male, Hispanic female, Asian American male, and Asian American female. The campaign activites asked about are along the X-axis. The chart gives the average for male and female respondents, respectively, who anticipated that a white male candidate would have an advantage in these aspects of a campaign.

Figure 6.5. Expectations of Advantage for a White Male Candidate, by Respondent Sex. Survey instructions: “Please mark which of the following type of candidates you think would have an advantage in the following list of campaign activities, if any.” Answer choice gave respondents a matrix of types of candidates (white male, white female, black male, black female, Hispanic male, Hispanic female, Asian American male, and Asian American female) and a series of campaign activites (listed along the X-axis). The chart gives the weighted average of a “yes” response for the white-male-candidate category, by respondent sex, for that type of campaign activity. The stars indicate statistically significant differences between the answers of male versus female respondents. Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. N = 713.

As the figure shows, large proportions of both male and female respondents anticipated that a white male candidate would have an advantage in most activities, but women thought so more than men. On average, women were nearly 20 percentage points more likely than men to think a white male candidate would have an advantage in these campaign activities. The gap wanes, as with “being perceived by voters as honest,” and waxes, with the largest gap showing up in “being forgiven for a minor character flaw or indiscretion.” In few activities did the majority of women agree with the majority of men; all of these averages are statistically significantly different by sex,65 with women always anticipating more advantage for a white male candidate.

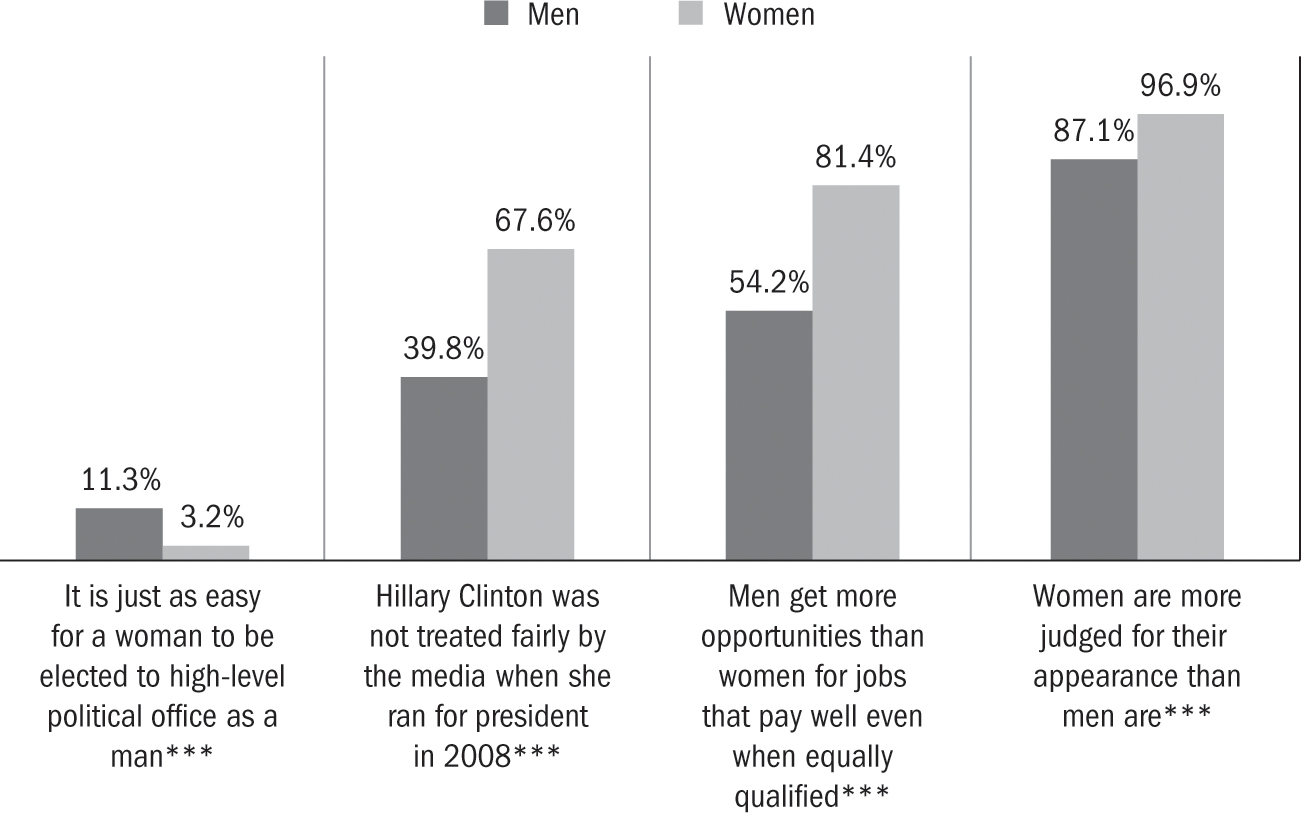

Factors other than previous discrimination may also give rise to expectations of bias against women in the political world, on the part of a number of political actors (voters, media, funders, and party leaders). Even without experiencing it oneself, one could observe and “read” discrimination in current U.S. politics. For example, although only a few in my survey sample knew the exact number of women in Congress, almost all (98 percent) believed that women were under-represented. (They were right—the current figure is 19 percent women in Congress, despite 51 percent of the U.S. population’s being female.66) And a majority of the sample (53.4 percent) believed that a specific woman, Hillary Clinton, was treated unfairly when she ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2008.67 A plurality of men thought this too, but women believed it more: 39.8 percent of the men thought Clinton was treated unfairly, compared with 67.6 percent of the women (and the difference between the sexes was strongly statistically significant).68 These sample means and others along this vein are displayed in figure 6.6.

Women in this sample, in other words, saw the political world as pretty strongly biased in favor of men.69 They saw race as well as sex bias, thinking for example that Hispanics/Latinos are generally portrayed negatively in the media. Men agreed, just not seeing quite as much bias. Almost no one thought that running for office was gender- or race-neutral.

To test this idea further, I created an index of expecting discrimation, which aggregated into one scale all the survey questions about discrimination (both race and gender) and standardized the index by dividing by the number of questions, as I had done before for both the costs and rewards indices. When the index was standardized by my dividing by the number of points possible, each person could score between 0 and 1 on this “expecting political discrimination” scale. Those scoring 1 or close to it expected a whole lot of bias in political campaigns, while those scoring around 0 saw little. As we would expect from the data given thus far, men and women both expected that those who are not white or male would face political discrimination, but women expected it more. On average, male respondents scored .37 on this index, while the corresponding figure for females was .52.70

Figure 6.6. Expectations of Gender Bias: Percent Agreeing with the Statement, by Sex. Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. * p<.1, ** p<.05, *** p<.01 (for difference between sexes). N = 763 (for all question except job opportunities). N = 716 (for Q on men versus women and job opportunities).

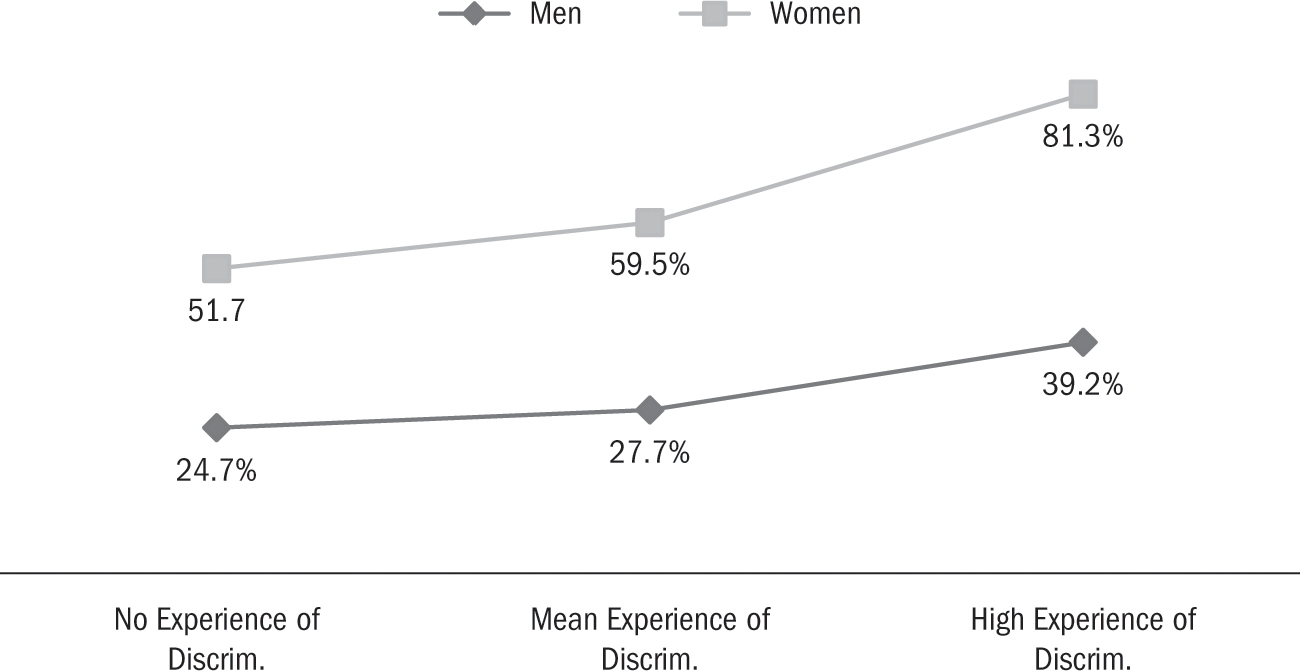

Having already experienced discrimination seems in the survey data to have heightened women’s perceptions of it in politics, but even those women who reported no personal experiences of discrimination expected that women would face it as candidates. Relatedly, men who had experienced some form of discrimination (racial, religious, or gender/sexual orientation) were more likely to see bias in U.S. politics. To give a simple illustration of how gender and discrimination experiences intersect in these kinds of expectations of discrimination, consider figure 6.7, giving means for different groups. This figure gives predicted probabilities of how likely one would be to expect discrimination against women and racial/ethnic minorities, based on whether one has already experienced discrimination. And the figure gives the probabilities separately for men versus women. It tells us that both one’s sex and one’s experiences of discrimination matter strongly in predicting how likely one will be to expect discrimination. Men who have not themselves experienced bias have about a 25 percent probability of expecting discrimination against women and minorities in politics and other realms. Men who have some experience with discrimination themselves are more likely to expect it for others (about 28 percent), while men who have faced a lot of bias have nearly a 40 percent probability of expecting discrimination.

Figure 6.7. Predicted Probabilities of Expecting Discrimination, by Sex and Experience of Discrimination. Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. N = 764.

Meantime, women as a group are already very likely to expect bias, but having already experienced discrimination is a very strong predictor of expecting it even more. Women with no experience of discrimination have about a 52 percent probability of expecting it, and women who have experienced some discrimination have about a 60 percent probability. Women who have had many experiences of discrimination have an 81 percent probability of expecting that women and racial/ethnic minorities will face bias. The upshot is that both gender and previous discrimination are significant predictors of expecting political discrimination, in other words—and those who expect it most are women who have faced it before.

Perceptions versus Reality

Whether the costs actually are higher for women as candidates is subject to debate; plenty of research has found that gender discrimination continues to exist on the part of voters, party leaders, media, and campaign donors, although recent research also finds that these biases are far smaller than they used to be (and are perhaps smaller than most people think).71 We know, for instance, that female candidates now regularly raise the same amounts of money as male candidates—although it also appears that women may have to work harder than men to raise that same amount of money, such as by making twice as many phone calls to donors.72 Research on media treatment of women as candidates finds that they are more likely than men to find themselves discussed in terms of their appearance (what Marie Wilson, formerly president of the Ms. Foundation for Women and the White House Project, has famously called “hair, hemlines, and husbands” coverage), less likely to be quoted in their own words, and more likely to be paraphrased.73

It appears that gender biases in recruitment of candidates persist, although in some places far more than others, and often because of social network effects rather than conscious discrimination.74 Researchers of women in business call these “second generation” discrimination effects and find them in recruitment for leadership in business as well.75 The model is that people in leadership (mostly white men) tend to mentor, support, and recruit people they already know, and/or with whom they feel most comfortable, who are often though not always similar to the existing leaders in terms of gender and race.76 Gender quotas, often within parties, have been effective in increasing the recruitment of women in more than one hundred other countries, including most of those in Europe, but are resisted strongly in the United States and would not make as much sense within our “candidate-centered” system here, where candidates often must self-recruit.77

In terms of voters, good research tells us that, in surveys, very few people admit to outright bias against voting for women as candidates.78 Indeed, political scientists Lawless and Fox use these figures to suggest that female candidates should just get out there and run79 more often, as they are over-expecting gender discrimination. However, think of it this way: if women are far less likely to run, and less likely to feel confident about and qualified to run, as these researchers have found, then generally only the most qualified and confident women end up as candidates, which helps explain why women tend to be higher-quality legislators80—social scientists call this a major selection bias. If what we see is mostly high-quality women running, but men of all candidate-qualities feel qualified to run (even if they are not),81 we should indeed see voter bias, just the other way. The rates of voting for women as candidates should be higher than the rates of voting for men, but they are not. Mere equality of voting rates for both types of candidates, then, is not really evidence of a lack of voter discrimination; indeed, it may be the opposite.

Biases continue to exist, in other words, but perceptions of discrimination among the sample may overestimate the extent of these biases. Or maybe not, if you believe (and some of the research is quite convincing on this point) that “second generation” discrimination is still pretty powerful. And more important, in the case of political ambition, as researchers have pointed out, perceptions are more powerful than reality.82 How and why respondents perceive gender biases in the acts of running for and/or holding political office—and how such expectations affect their political ambition—is what is most relevant. And the answer is that they perceive a whole lot of bias, and it seems to have quite a large effect.

Cumulative Effects: Women More Deterred

When added to the perceived costs one might face in running for office, anticipation of discrimination further led women (and especially women of color, whom I will discuss specifically in the next chapter) to see more costs than benefits. Why play a game when the deck is stacked against you, and especially if you do not much like what you may get if you win?

Three related but theoretically distinct mechanisms are thus at work in creating the difference we observe between women’s and men’s political ambition. The first is that for women, the costs of running for office just seem higher (even before adding in expectations of bias). On average, if we look at the sexes separately on the costs index from chapter 5, we see that men scored .32 and women .36.83 Women on average saw higher costs, in other words, and the difference is strongly statistically significant.84 The second mechanism is that women on average saw lower rewards. On the “rewards index,” men on average scored .37 and women .32, with the difference again being strongly statistically significant.85

The third mechanism is that women as a group, and especially those who had already faced discrimination, expected that as candidates they would face a whole set of costs relating to gender bias. Many expected fairly high levels of bias and double standards, particularly thinking that women would be more likely to be judged by their appearance, that white men would have advantages in most aspects of campaigning, and that Hillary Clinton was treated unfairly in her 2008 run for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Let’s add data on that third mechanism to the previous costs-rewards integrated framework of analysis. Expecting to face discrimination as a candidate could be thought of as a cost to running. In line with the way the costs index was constructed, we can give those expecting some discrimination a 1, while those who expect a lot of discrimination get a 2. (This will also change the denominator of the ratio, that calculation of how many points are possible overall, so I will adjust the formula accordingly.) The addition of this new cost to running also affects the overall score we get when we subtract total costs from total rewards, so I will recalculate that score for each person as well.

If we re-map the distribution curves of men’s versus women’s perceptions of rewards-minus-costs, as in figure 6.8, we see that adding in perceptions of a biased political world exacerbates yet furthers the existing gender split on costs and rewards. These curves still overlap, but not quite as much as before. Now, as figure 6.8 shows, the average of the summary measure (rewards minus costs) falls further behind the 0 line for women. Taking seriously the expectation of gender bias, in other words, makes costs more clearly outweigh rewards for women as a whole.

Figure 6.8. Revised Distribution Curves of Rewards-Minus-Costs Index Scores, by Sex. Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. N = 764.

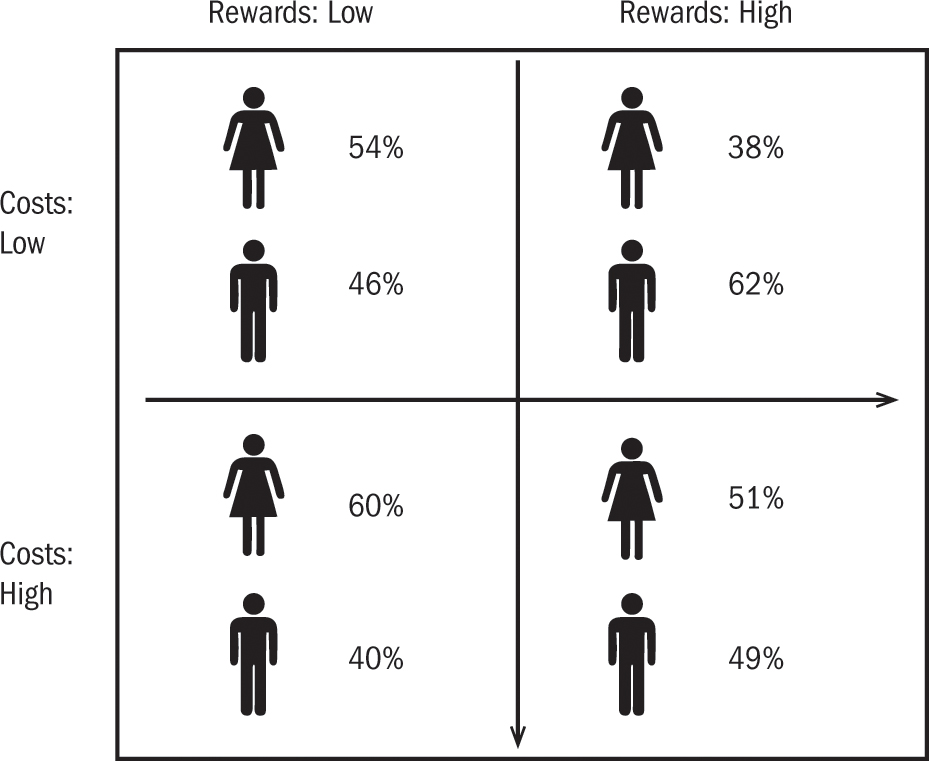

Figure 6.9. 2x2 Matrix: Costs Dummy versus Rewards Dummy, by Sex. Source: LPS-PAS, Survey Sample. N = 763. Notes: “Low” here signifies falling below the sample mean for that index. “High” signifies above the sample mean. Chart gives distribution of women versus men in each cell.

Figure 6.9 revisits the 2x2 matrix of costs and rewards developed in the previous chapter, this time looking at the distribution of men and women across the four cells. Looking at the distributions of men versus women in each cell of the matrix in figure 6.9 is instructive. Women are most plentiful in the two low-rewards boxes and are least likely to be in the box of those seeing high rewards but low costs.

Summary

The men and women in this elite sample should be, and in many ways are, more alike than they are different. However, certain items show very strong differences between men and women, and many of these relate to running for public office. From the evidence presented here, it appears that women in general are less likely than men to think that politics is of use in solving the problems they care about—and this correlates strongly with political ambition.86 Also, women have been far more likely than men to have experienced discrimination and are much more likely to expect to face it in the electoral arena, should they run. Women, more than men, see running as a game that is stacked against them.

Differing perceptions of the usefulness of politics by sex and differing experiences with discrimination both seem extremely related to the disparate levels of political ambition between men and women. Even before we add the expectation of discrimination as a cost, women saw higher costs and lower rewards to candidacy than did men. However, the vehemence with which interview respondents spoke about bias in the electoral arena and the high numbers of the survey sample expressing concerns about such biases together suggest that such expectations should indeed be considered as part of a rational cost-benefit analysis. When they are added to the rewards-minus-costs index, women as a whole fall far below the zero-line. And women, despite being fully half of the sample, were only 38 percent of the people in “high rewards, low costs” box of the 2x2 matrix. Instead, they were disproportionally clumped in the “low rewards” boxes (see figure 6.8).

As studies have found, certain personality characteristics, such as confidence, differ across men and women as groups. Such characteristics may partially account for women’s relative reluctance to run for office.87 But the larger story is that almost everyone in the sample saw costs to running for and holding office, and only a narrow slice saw compensating rewards. For women as a group compared with men as a group, the costs just seem higher and the rewards seem lower. On the other hand, those who did have high political ambition—both women and men—were very likely to see politics as useful in solving important problems. Future research should investigate this connection more thoroughly, and the origins of positive perceptions of politics more generally.