CHAPTER Four

Guiding Principles for Teaching Children with Trauma

Although many educators feel that young children will outgrow the effects of trauma, this is a mistaken belief. Young children are both the most vulnerable of populations and the most deeply influenced by trauma (Nicholson, Perez, & Kurtz 2019).

Three-year-old Liam has never had trouble falling asleep during rest time. Even after wildfires forced his family to flee their home six weeks ago, Liam has slept well, hugging his stuffed penguin, Pablo, closely to his tummy. Lately though, Liam has become anxious as rest time approaches. His educator, Ms. Sherrow, shares her concern with Liam’s mom: “It’s almost like he is scared to fall asleep.” Ms. Sherrow is observing that signs of trauma may lay dormant and suddenly appear well after the trauma itself has ended.

• • • •

Five-year-old Emma has never missed a day of school. At the home visit before kindergarten started, Emma’s grandmother, with whom she lives, shared with her teacher, Ms. Garcia, that Emma had been sexually abused by a family member when she was 2 and 3 years old. Ms. Garcia is surprised that despite the severe trauma in her life, Emma never acts out in the classroom. In fact, she seems to be in her own world, often staring into space. Emma keeps to herself and never bothers anyone. What Ms. Garcia has not yet realized is that Emma’s withdrawal and daydreaming are very much signs of trauma, too.

Experiences like Liam’s and Emma’s are not unique. Children are not immune to aftereffects from natural disasters, abuse, and other adverse experiences. As you’ve read in the previous chapters, trauma negatively affects children’s developing brains and bodies and has the potential to cause lifelong damage.

However, over the last 20 years or so, much has been learned about trauma and how a healing-centered approach can help children recover from these negative experiences. Indeed, coupling your expertise with the support of colleagues, specialists, families, and community leaders has the potential to ensure that children are not doomed by their past.

In this chapter we offer foundational information on basic principles that can be used to inform and guide your interactions with children. Chapters 5, 6, and 7 will discuss how to use these approaches in your day-to-day teaching practice. The following principles offer overarching guidance on teaching children exposed to trauma.

Principle 1: Recognize that All Children Will Benefit from a Trauma-Informed Approach

TIC focuses on social and emotional supports to help children learn to self-calm, regulate their emotions, and focus on learning. It is rooted in relationships and trust and emphasizes safety, predictability, and consistency. These are important social and emotional supports for every young child, so using a trauma-informed approach serves everyone in your program. By supporting the development of skills such as executive function, making friends, problem solving, and empathy, you are readying every child you teach for learning and school success.

As noted in Chapter 1, you may not be certain whether a child has been affected by trauma or not. Not all instances of trauma are readily identifiable. Some children with ACEs may be known to you because the child welfare system is involved in their lives. However, some children with ACEs may never be known to you. While it is possible with parental permission to screen all children in your program for trauma and then link the results to service delivery systems such as a multitiered system of support (MTSS), doing so is a debatable approach. As of 2016, only one in eight schools at every level in the United States was making use of universal screening (Eklund & Rossen 2016).

In this book, we do not recommend the use of universal screening by schools or programs. For one thing, screening can lead to embarrassment or shame. Being known as a child who receives special treatment sets one apart from one’s peers. Since one of the primary goals of recovery is to normalize life for a child exposed to trauma, no child should feel less than normal because of what they have experienced in life. “The best approach is to make sure we provide trauma-sensitive learning environments for all children” (Cole et al. 2013, 9).

Even when educators are aware of specific children having experienced trauma, they cannot assume that they know the extent of the children’s traumas or the underlying causes. Very often there is more to the story that hasn’t been uncovered. As the Council for Professional Recognition (2019) cautions early childhood educators, “You don’t need to know exactly what caused the trauma to be able to help. Instead of focusing on the specifics of a stressful situation, concentrate on the support you can give. Stick with what you see—the hurt, anger, and worry—instead of getting every detail of a child’s story” (6).

Providing the same social and emotional supports to all children in your classroom or family child care program will help ensure that no child who has experienced trauma will slip through the cracks. And every child will be enriched by your sensitive asset-building teaching.

Principle 2: Use a Strengths-Based Approach to Teaching

A natural impulse for many educators is to assess what a child’s problems are and then try to fix them. You may even wonder whether children so traumatized by their experiences can ever become healthy. Yet when working with children who have been frightened and disoriented by immigration experiences, beaten down by abuse, or depressed by loss, focusing on what’s wrong both makes the problems worse and tends to leave children disengaged (Lewis 2015). Instead of focusing on what a child is lacking, build on what the child knows and can do. Strengths-based teaching has educators help children assess what they do well and then use these strengths and talents to build and bridge knowledge. You do this by focusing on the following (Zacarian, Alvarez-Ortiz, & Haynes 2017b):

❯ Identifying children’s existing strengths

❯ Honoring, valuing, and acknowledging these strengths

❯ Helping students become aware of their strengths

❯ Building instructional programming that boosts social ties and networks by drawing from children’s strengths

Drawing on children’s strengths and capacities builds resilience and helps them develop the skills, competencies, and confidence they need to become active learners and critical thinkers. It also leads to improved educational outcomes, more success, increased engagement, and even greater happiness (Biswas-Diener, Kashdan, & Gurpal 2011; Ginwright 2018; SAMHSA 2014b; Zacarian, Alvarez-Ortiz, & Haynes 2017b). This doesn’t mean that you deny the existence of barriers and challenges to the children’s learning, but that you use your energy and attention to intentionally focus on children’s assets.

You’ll find that it doesn’t take great effort to identify strengths in young children, even when trauma has left them with great challenges. So much growth and development take place during the preschool and kindergarten years that there is always some new strength and capacity that emerges: “You sang ‘Itsy, Bitsy Spider’ all by yourself, Anyah! Maybe you and Keily would like to sing the song to all of us at our afternoon meeting.”

Strengths-based teaching is especially well suited to children who have had trauma in their lives (Zacarian, Alvarez-Ortiz, & Haynes 2017a). It allows educators to focus on the whole child rather than the trauma or the child’s behavior. This means looking at the child’s personality, relationships, family and community values and beliefs, interests and dislikes, protective factors, support systems, and other capacities (Nicholson, Perez, & Kurtz 2019).

Proponents of a strengths-based approach envision children’s assets as being like individual tiles in a mosaic. Each strength may not stand out individually, but all the tiles taken together become a unified piece of art (Zacarian, Alvarez-Ortiz, & Haynes 2017a). As an educator, your mission is to take all a child’s individual tiles—or assets—and use them as a foundation for helping that child learn and succeed.

Principle 3: Recognize, Appreciate, and Address Differing Influences on Children’s Experiences with Trauma

Chapter 2 discussed some of the ways factors such as race, culture, language, socioeconomic status, disability, and gender influence the experience of trauma for children and how bias and discrimination in response to such aspects of children’s identities can be a source of trauma (Carter 2006; Hughes & Tucker 2018; Stevens 2015). A key part of individualizing your approach and making use of trauma-sensitive guidelines is to view children’s experiences through these lenses. While none of these influences predetermine a child’s response, they are an important part of the picture when determining how to best reach and teach individual children.

Here are some fundamental actions you can take as you seek to better understand the influences on individual children’s experience of trauma:

❯ Get to know every family and child well. Understanding another person can strip away stereotypes and replace them with respect, understanding, and appreciation of differences as well as similarities. Do not assume that people who share a cultural or other identity have the same experiences or follow the same traditions. Knowing the specific country a family has emigrated from, for instance, is helpful in better understanding that family. Even more helpful is learning to know their individual experiences and practices.

❯ Know yourself. Examine your own biases for preconceived notions and ways in which your own background and experiences might influence how you interact with children and families. Reflect on the language (both spoken and body language) you use to make sure that you are not inflicting microaggressions (see Chapter 2). Videorecord yourself during children’s play and group times to study your responses to children to determine any biases you may be acting on.

❯ Support children’s identities through books, music, toys and other materials, language, and cooking experiences that reflect the children, families, and their communities. Have dress-up clothes and props for dramatic play that are familiar to children, including open-ended pieces that can be used in multiple ways and items that are representative of their communities. Encourage children to have pride in who they are and to appreciate others for who they are.

❯ Read aloud, discuss, and have children act out in skits and with puppets storybooks that deal with trauma through specific lenses such as race, culture, or gender. For example, Ouch! Moments: When Words Are Used in Hurtful Ways (by Michael Genhart) addresses racial microaggressions.

❯ Work to forge a bond with each child, bearing in mind how factors like differences in home language, culture, and race may affect your interactions and the child’s responses. Designate one-on-one time every day.

❯ Offer play experiences that children can participate in regardless of language. Art, sand and water play, and music are open-ended experiences where all children can express themselves.

❯ Connect with community groups that serve migrant and refugee families for ongoing support, ideas, and knowledge of how to better serve families in their home languages.

❯ For children with disabilities or developmental delays, who often need predictability to be successful, avoid changes to the daily routine and environment as much as possible to alleviate the stress that children often experience following trauma (CDC 2019). Offer soothing sensory techniques such as drawing, deep breathing, mindfulness, yoga, or exercising to manage emotions. As described in Principles 5 and 6, focus on building children’s self-regulation skills, not just working to reduce challenging behaviors (Rossen 2018).

❯ While children display a variety of reactions to trauma, keep in mind that that there are gender differences in children’s reactions to trauma and their resilience. In general, girls experience depression and anxiety following trauma, while boys show more anger and act aggressively (Epstein & Gonzalez, n.d; Foster, Kuperminc, & Price 2004). Mindfulness is an important strategy for helping children regardless of gender develop needed self-regulation. See Chapter 6 for more on mindfulness.

❯ Perhaps most important, be an advocate for all children and families, particularly those whose experience of trauma may be affected by the factors discussed here. Chapter 8 suggests several ways you can do this.

Principle 4: Embrace Resilience as a Goal for Every Child

As an educator, you want many things for children: to master the goals in the curriculum; to develop a love of learning and a sense of curiosity; to be creative; to think critically; to appreciate the arts; to be kind and empathic; to make responsible decisions and solve problems; to feel capable, competent, and confident; to be able to reach their full potential; and to feel optimistic about themselves, others, and the world they live in. Touching on all these goals is a desire for children to be resilient—to be able to overcome whatever adversities they have been exposed to so they can learn and reach their full potential. It’s important that even children who have not been exposed to trauma be resilient so that they are prepared for whatever challenges life throws their way.

Culture is among the factors that influence children’s resilience, and it has a strong influence on both a child’s reaction to trauma and recovery from it (Raghavan & Sandanapitchai 2019). Clauss-Ehlers (2004) uses the term “cultural resilience” to express how cultural values, language, customs, and norms can be used to fortify oneself against adversity. Examining the cultural supports that work as protective factors in creating children’s resilience will help you focus on what builds resilience rather than what chips away at it.

In addition to cultural supports that encourage the development of resilience, some children are more resilient than others due to temperament and factors such as caregiver–infant attachment. But for the most part, children’s resilience skills need to be nurtured and supported. As trauma pioneer Bruce Perry reminds us, “Resilient children are made, not born” (Grogan 2013).

The good news is that the number one way of fostering resilience in children is also the number one activity you should be doing anyway. According to the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (n.d. c), “The single most common factor for children who develop resilience is at least one stable and committed relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver, or other adult.” You can be that person for the children in your program. Chapter 6 delves into building relationships with children.

In addition to forming a strong positive relationship with children, teachers can help children develop these critical skills to boost their resilience (Pearson & Hall 2017; Reivich & Shatté 2002):

1. Emotional regulation—the ability to keep emotions in check and not be overwhelmed by feelings

2. Impulse control—the ability to stop and choose whether to act on a desire to do something or to delay gratification

3. Causal analysis—the ability to analyze and accurately decide what caused the problem being faced

4. Realistic optimism—the ability to maintain a positive thinking style without ignoring real-life constraints

5. Empathy—the ability to understand the feelings and needs of others

6. Self-efficacy—the belief in one’s own abilities to succeed and make a difference in the world

7. Reaching out—the ability to learn from mistakes and take on new opportunities

Many of these skills are explored further in the guiding principles that follow. By working one-on-one with each child, you can foster resilience that will predispose children to both recover from trauma and be ready to learn and succeed.

Principle 5: Help Children Learn to Regulate Their Emotions

According to resilience researcher Andrew Shatté, emotional regulation is the most important ability associated with resilience (Pearson & Hall 2017). Children who have experienced trauma may be easily triggered by sounds, smells, sights, and misconstrued words and actions into a fight-flight-freeze reactive mode (National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments, n.d.). At these times, their stress hormone levels increase and survival becomes their focus. Learning is put on hold when body and brain are on alert (Center on the Developing Child, n.d. e). Your primary focus is on how to turn this situation around.

One major part of your strategy should concentrate on setting up the program environment to reduce triggers. Chapter 5 provides guidance on how to design a space and plan a schedule to make children feel safe and comfortable. When triggers do arise for a child—perhaps a backfiring car sounds like a gunshot or a thunderstorm brings back memories of flooding—use a two-step approach: first, help children calm down, and second, when their stress has been reduced, help them learn how to regulate their emotions. By doing so, you open children up to a chance to focus on learning: “Children who have experienced adversities but demonstrate adaptive behaviors, such as the ability to manage their emotions, are more likely to have positive outcomes” (Murphey & Sacks 2018, 10).

When children are overwrought, angry, and acting out, go with them to the calming area in your classroom (see Chapter 5). Help the child release the intense feelings by squeezing balls and other pliable toys, playing with sensory materials, doing deep breathing exercises, reading books about characters who have similar emotions, listening and moving to music, or rocking tenderly with you.

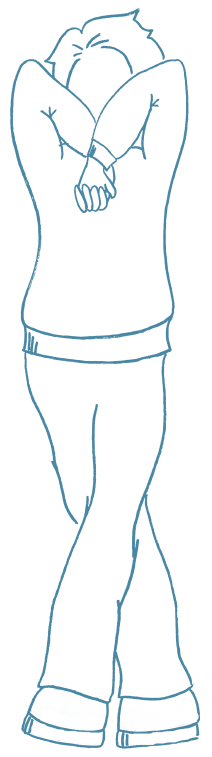

You might also try what are known as mental “hookups”—physical exercises designed specifically to help children calm down during meltdowns or periods of high anxiety (see Fig. 5). You can do this by having a child stand with their legs and arms crossed in front of their body. The child places the palms of their hands against each other, with the fingers interlocked. Then ask the child to loop their hands underneath their arms in a pretzel fashion and hold that position for as long as they can, with two to five minutes being the ideal. This exercise uses movement to refocus the brain’s activity and help the child calm themselves (Integrated Learning Strategies 2017).

When children have calmed, they are ready to learn some ways to regulate their emotions. Emotional regulation involves both cognitive and psychological processes, including becoming aware of one’s feelings, learning the difference between emotional states, tolerating feelings without fear of losing control and expressing them safely, and moving from co-regulation with the help of an adult to self-regulation (Craig 2008).

Remember that emotional regulation is a skill, and like all skills, it takes continuing practice to be learned and mastered. Here are some ways you can work on emotional regulation with children:

❯ Be a role model always. Talk calmly, quietly, and warmly, sometimes known as “low and slow.” Share your own feelings and what you do to keep them under control with children. Your calming behavior can be contagious to children who are dysregulated.

❯ Use feeling charts to help children learn to identify and label feelings. Charts can be easily made using emoticons or photographs of children in the program posing to represent a variety of feelings.

❯ Encourage children to make drawings, paintings, or collages of faces to illustrate different feelings, noting how colors can be used to express emotions.

❯ Provide children with ideas for different activities they can do to deal with a feeling they are experiencing. For example, if they feel scared, they can talk with a teacher about it and plan for how to address their fear. They could also cuddle up with a stuffed animal and a blanket on a beanbag chair for comfort, act out what has scared them in dramatic play, or focus on something fun that will take their mind in a different direction, such as playing outside on the slide with a friend.

❯ Use books about feelings to give children the vocabulary they need to describe their emotions. Go beyond basic labels like happy and sad—identify emotions and facial expressions as delighted, thrilled, or cheery. This builds vocabulary and teaches synonyms, and it helps children learn to identify the nuances of emotions.

❯ Teach children to take notice of how their body feels and how to put those feelings into words: “I see that your hands are in fists. I wonder how you are feeling inside that made you tighten your hands like that.”

❯ Offer sensory activities like sand play, water play, and finger painting every day for children to work through emotions. Provide soothing natural materials to explore.

❯ Take children outdoors every day where they can exercise and use their large muscles and loud voices.

Figure 5. Using the hookup move to self-calm.

❯ Encourage dramatic play so children can express emotions and work through their fears by role playing. If a child needs help regulating emotions, occasionally enter the play: “I hear you yelling at the baby doll because she won’t stop crying. That must be very frustrating that she won’t stop. I wonder what else you could try to help her calm down.”

❯ Put on skits and puppet shows and use persona dolls (dolls given a particular identity and treated as classmates and friends who often invite children to help solve a problem) to act out the main characters expressing their emotions acceptably.

❯ Help children problem solve and reframe frustrated thinking: “It’s hard to wait for snack time when we’re hungry. What can we make for our afternoon snack that we will be able to eat right away without having to wait to warm it up?”

❯ Encourage children to use self-talk to calm themselves down and to manage challenges: “When I get discouraged or worried, sometimes I give myself pep talks in my head. I tell myself, ‘I’m really good at drawing. I bet I can make beautiful roses on this cake out of icing.’ I wonder if that would help you.”

❯ Help children use tools to keep their emotions in check, such as deep breathing, yoga poses, and visualization techniques.

❯ Display a “Cooling Off” poster with words and photos that convey strategies for regulating feelings. Some suggestions might be drawing, listening to calm music, shaking a glitter jar (see Appendix 3), walking with an adult, taking a deep belly breath, and crumpling paper and tossing it in a basket (Nicholson, Perez, & Kurtz 2019). Near the poster, place materials in a basket that correspond to some of the strategies.

As children gradually move from co-regulating with your assistance to self-regulating, they are less likely to be ruled by their emotions and can better maintain a state of being present.

Principle 6: Use Positive Guidance When Dealing with Children’s Challenging Behaviors

Let’s cut to the chase: Punishment, suspension, and expulsion are inappropriate for any young child. While the symptoms and behaviors that typically accompany experiencing trauma can challenge the patience of any educator, it is vital to always keep in mind that children are not trying to grate on your nerves or to intentionally misbehave. They are dealing with fears, and their brains are in survival mode. This state leads many children to act out in ways that disturb others. Take, for example, Hugh:

Hugh’s mother has been addicted to drugs since before Hugh’s birth. A neighbor continually complained to authorities that 5-year-old Hugh was being left alone. Nothing happened until a few months ago when Hugh found some matches and started a fire big enough for the fire department to have to come and extinguish it. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but Hugh was removed from his home and placed in foster care. He is quiet and withdrawn at his new foster home, barely speaking even when asked a question. At preschool, however, he pushes others when they are in his way, tells other children what to do, and demands that things be done his way.

Ms. Stafford, his preschool teacher, has tried several techniques to address the behaviors, starting with positive reinforcement for good behaviors. This technique has worked well with many other children. Disappointed when this brings no change in Hugh’s behavior, she tries scolding, taking away privileges, shaming (for keeping everyone from being able to eat lunch because Hugh won’t take a seat), and ignoring (when Hugh starts yelling and throwing things outside). Not wanting to resort to more severe punishments when those approaches don’t work, Ms. Stafford talks the situation over with colleagues and becomes convinced that the solution to Hugh’s aggressive behavior is to put Hugh in time-out and have him reflect on his behavior.

In time-out, however, Hugh sits in the chair and holds onto its sides and jumps with the chair. Thinking Hugh will eventually tire of this behavior, Ms. Stafford assigns Hugh to time-out for most the day. In a test of wills, neither Ms. Stafford nor Hugh will relent.

Ms. Stafford is now at her wit’s end. Her traditional approach to guidance has had no effect on Hugh’s challenging behaviors other than to escalate them. Hugh’s behavior and outlook are deteriorating, and Ms. Stafford is out of ideas and patience.

Ms. Stafford believes that Hugh is intentionally misbehaving. She fails to understand that Hugh is in reaction mode. His brain is in a fight-flight-freeze frame of mind, seeking survival. Putting Hugh in time-out triggers his feelings of abandonment and not being cared about. Moreover, it does nothing to help Hugh regulate his emotions. As experts on trauma-sensitive care have noted, “Time-outs will be terrifying to children with trauma histories. Being abandoned and sent away as a punishment will be more triggering” (Nicholson, Perez, & Kurtz 2019, 161).

Time-out, zero-tolerance policies, and other punitive discipline techniques have little effect on changing the behavior of any child. For children like Hugh, they can have the additional ill effect of retraumatizing the child and sending the child a message that they are unlikeable. Ms. Stafford must help Hugh regulate his emotions in a safe place. Until he is calm and can release his fear, Hugh will have difficulty focusing on learning and interacting with others in positive ways. To this end, Ms. Stafford might try some of the following techniques (Downing 2016; Jennings 2019b; Nicholson, Perez, & Kurtz 2019):

❯ Rather than time-out, offer Hugh “time-in.” This is an invitation for a child and teacher to sit together and connect. It enables children to feel safe and in control—factors that have been missing from Hugh’s life.

❯ Speak calmly and in a lowered voice when Hugh pushes a child or throws a chair or blocks. “Hugh, I can see that you are upset, but I can’t let you throw things or hurt anyone. Let’s go to the calming corner. You can throw beanbags or squeeze the squishy balls to get rid of your unhappy feelings. I’m going to sit there with you until you’re feeling better.”

❯ Refrain from asking Hugh to explain his behavior by asking questions like “Why did you jump in the chair? Couldn’t you at least have sat still in time-out?” Hugh may be just as puzzled by the way he acts as Ms. Stafford is. Children with a history of trauma (and most young children in general) have little self-knowledge or understanding of why they behave as they do.

❯ Acknowledge Hugh’s feelings: “I can see that you’re getting frustrated with the puzzle. I get that way at times, too. You might enjoy doing the one with fruit instead. I know that you like bananas and grapes a lot.”

❯ Offer Hugh choices (all of which are acceptable to Ms. Stafford) so that he gains a sense of control: “Hugh, would you rather squeeze one of the stress balls or read a book with me?” When he is calm, the teacher could even offer Hugh choices regarding his behavior when it has been out of control: “Hugh, when you had an outburst this morning, you were very upset, and so was I. Let’s think of some things you might do to help you calm down when you feel this way.” This approach gives Hugh some control over his behavior without making him explain why this behavior occurred.

❯ Let Hugh know what he should be doing rather than what he shouldn’t be doing: “Hugh, I’d like you to come sit at the lunch table next to me” rather than “Hugh, we’re all hungry and you’re wasting everyone’s time by just standing there.”

❯ Offer Hugh and all children an opportunity to participate in making classroom rules. Children are more likely to buy in and follow the rules when they have had a say in developing them: “Everyone, Hugh is suggesting that we need a rule that if we want to run, we need to do it outside. What do you think? That would mean that indoors we walk or sit or lie down, but we won’t run.”

Who Gets Expelled?

As far back as 2005, researcher Walter Gilliam found that preschoolers were being expelled at a rate three times higher than were children in grades K–12. For children enrolled in non-state-run pre-K programs, the rate was 13 times higher than in K–12 (Gilliam 2005).

Today, the rate of expulsion remains unacceptably high—more than 5,000 pre-K children are expelled each year (Council for Professional Recognition 2019). This translates into roughly 250 preschool children being suspended or expelled every single day (Malik 2017).

Hugh’s behavior in the program, and Ms. Stafford’s frustration at not being able to successfully address it, puts him at risk of being suspended or expelled. Being male puts him at an even greater risk: Boys compose 54 percent of the preschool population, yet 79 percent of preschool suspensions happen to boys. Moreover, boys represent 82 percent of children suspended multiple times (US Department of Education Office for Civil Rights 2014).

If Hugh had a disability, the odds of suspension or expulsion would likewise increase. Students with disabilities receive twice as many of these disciplinary actions as do their peers without disabilities (US Department of Education Office for Civil Rights 2014).

And if Hugh were Black, Latino, or Native American, the likelihood of his suspension or expulsion would go up even more. Black children are suspended or expelled at 3.2 times the rate of White children. Native American children have a rate 2 times that of their White counterparts, and Latino children are suspended or expelled 1.3 times as often as White children (Owens & McLanahan 2019).

Part of the reason for the discrepancy in treatment is that schools serving children of color and children from low-income families are more likely than other schools to adopt zero-tolerance policies toward children’s misbehaviors (Welch & Payne 2010). In these schools, even minor infractions can lead to punishments such as immediate suspension or expulsion.

But beyond this, there is documented differential treatment in the way preschool teachers and administrators treat children of different races. A Yale Child Center study found that educators of all races spend more time watching Black youngsters for disruptive behaviors than they do their White classmates (Wright 2020). Black boys in particular are at the receiving end of teachers’ expectations of problem behaviors. They are given harsher disciplinary actions than are White boys exhibiting the same behaviors (Gilliam et al. 2016). Among all races, Black teachers hold the highest standards for Black boys’ behavior (Mwenelupembe 2020).

These punitive practices serve no one—least of all the children. Expelled preschool children are more likely to be unprepared when they enter formal schooling in kindergarten. This negative impact carries on throughout their school careers, including a higher risk for school failure (Council for Professional Recognition 2019).

❯ Let Hugh know that you have positive expectations that he will be following the classroom rules. “Hugh, I know that you’ll be able to put the blocks on the shelf when you’re done playing with them. Thank you.”

❯ Choose words that de-escalate tensions, such as “I wonder if …” or “Let’s try …” or “Suppose we …” or “I wonder if we moved the easel outside if you’d enjoy painting where there’s more space. I bet the fresh air will feel good, too.”

❯ Credit Hugh publicly whenever it is appropriate to do so: “Thank you for bringing over the book so that I can read it to you and Tessa. That was very thoughtful of you, Hugh.” If the teacher needs to call attention to negative behavior, however, she should do it privately by calling Hugh over to a place away from the others, having him sit him down, and quietly telling him, “Hugh, you know that we have a rule that you can’t throw things. In fact, you helped make this rule. You might have hit someone when you threw that block. My job is to keep everyone in this classroom safe—including you.”

If Ms. Stafford were to continue to treat Hugh’s outbursts as misbehavior rather than as symptoms of a deeper problem, the result for Hugh would very likely be suspension or even expulsion from preschool. Children like Hugh, who are not being responded to with social and emotional support, try educators’ patience and all too often the only recourse seems to be removing the child from the program (see “Who Gets Expelled?”).

While suspension and expulsion are a disservice to any child, for the traumatized child, it can do irreversible damage. Expulsion is another form of trauma. It only serves to reinforce for children that they are not wanted, destroying any relationship that may have been formed with their teacher. Rather than remediate the situation, it sets children back even further. Suspension and expulsion ought never be regarded as a possibility for young children.

Principle 7: Be a Role Model to Children on How to Act and Approach Learning

Teachers and parents have the power to influence what children think, feel, and do. If you like singing “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes,” reading Pete the Cat books, and making homemade granola for snacks, those will be the favorites of many of the children. They look to you for guidance, inspiration, and validation—and for assistance in maneuvering the complexities of life.

By following your lead, children can begin to heal from trauma and become engaged learners. Think about how you might model the following and use these activities to help children grow and learn:

❯ How to use the indoor and outdoor spaces to play independently or with a friend, a small group, or the whole group

❯ How to read books, write, and count

❯ How to appreciate nature, garden, and nurture pets

❯ How to create art and music and how to dance

❯ How to make, maintain, and support friendships

❯ How to attentively listen to others

❯ How to self-calm and self-regulate

❯ How to build on people’s strengths, not their weaknesses or failings

❯ How to be realistically optimistic

❯ How to listen and react with empathy

❯ How to be kind and grateful

❯ How to solve problems

❯ How to learn from failures

❯ How to use positive self-talk as a resilience technique

❯ How to laugh, enjoy oneself, and have fun while learning

Principle 8: Help Children Turn Negative Thinking Around

Many children who have experienced trauma have had to deal with great negativity in their lives. This can lead children to act in unpleasant ways, making them difficult to be around. Children who have experienced trauma may misinterpret others’ actions and attribute negative intent when there is none. They may focus on their own pessimistic thoughts. For many children who have experienced trauma, life feels like an ongoing worst-case scenario.

A key strategy in building resilience in young children is for them to develop thinking that is realistically optimistic. You can do this with children by gently disputing their negative thinking and showing them when it’s not rooted in fact.

Optimism can be learned, no matter how innately pessimistic a person may be or how negative their life circumstances have been (Seligman 2005). By going through what has been dubbed the ABCDE model, educators can help children as young as 2½ learn to reframe their negative thinking to be positive (Hall & Pearson 2004). Here’s how the model works (based on Colker & Koralek 2019 and Seligman 2005):

A = an adverse event

For the purposes of this example, the teacher, Ms. Jones, asks 4-year-old Oliver to leave the sand table and find a new place to play.

B = beliefs and thoughts about the adverse event

Oliver reads into the request and takes it as a command, which is triggering for him. His teacher takes away the choice he had in deciding to play at the sand table, which makes him feel like he has no control. He interprets his teacher’s behavior as being punishing and targeted at him. He feels that Ms. Jones clearly doesn’t like him.

C = the consequences of having these thoughts and beliefs

Oliver goes into survival mode and gets very angry. He throws a bunch of props into the sand table, nearly hitting some children playing there, and shouts at Ms. Jones, “You’re being mean. You’re always mean to me. I hate it here. You like everyone but me.”

Ms. Jones asks Oliver to accompany her to the calming corner: “Oliver, I can see that you are very upset. Let’s go to the calming corner together. Why don’t you throw some sensory balls at the target or hit a punching doll, if you prefer. That will help you get rid of some of these feelings that are so strong. Afterward, when you feel a bit calmer, we can talk.”

Once Oliver gets more control over his emotions, Ms. Jones sits facing Oliver on beanbag chairs, and continues with the model.

D = disputation of the pessimistic beliefs

Ms. Jones begins by calmly explaining why she asked Oliver to leave the sand play area: “I am sorry that you thought I was mean. That was most certainly not my intent. The problem was that there were too many children at the sand table. It was getting too crowded for everyone to safely play there. You were the first to arrive there, so I asked you to move on because other children did not have such a long turn.”

Ms. Jones also disputes Oliver’s interpretation that she didn’t like him by recalling many times when she demonstrated her positive feelings toward him. “At lunch today I asked you to help set the tables with me. Yesterday, after you fell off your trike, I cleaned the scrape and gave you a big hug. And last week at group time, I asked you to sit next to me and help take attendance. Can you think about how you felt at these times? I hope you know that I like you a lot.”

After Oliver reflects on Ms. Jones’s words, he nods and admits that those were nice times.

E = energization from successfully disputing the negative thoughts and realizing that the situation is not as feared

Oliver feels better about his relationship with Ms. Jones and why she asked him to leave the sand table. Now he doesn’t mind leaving and asks Ms. Jones if they can read a book together in the library center.

Obviously, it will take more than a one-time conversation like the one Ms. Jones had with Oliver to change his negative thinking. Using the ABCDE process repeatedly and regularly will help children like Oliver who tend to instinctively think negatively to develop a positive thinking style. Each time you hear a child expressing their negative thinking, take the opportunity to help the child regulate their emotions and then help them reframe their negative thinking in a positive way.

For some children, learning to self-regulate emotions and dispute negative thoughts is a straightforward process. For others whose negative thinking runs deep, it will take considerable time. As always, be patient.

One final point about the above example: Ms. Jones should examine her own thinking for possible bias toward Oliver. Is there some truth to Oliver’s assertion that she doesn’t like him? How might his challenging behavior be consciously or unconsciously affecting how she interacts with him?

Turning children’s negative thinking into optimism offers profound benefits. Optimists, as compared to pessimists, are healthier, live an average of nine years longer than pessimists, and have happier, more fulfilling lives (Colker & Koralek 2019). Optimism is correlated with self-efficacy, problem-solving skills, and the ability to learn from mistakes (Seligman 2007). These are the same skills that children exposed to trauma often lack and need so they can prosper in preschool and kindergarten.

Principle 9: Enrich Children’s Lives with Art, Music, and Dance

All people need art to have a fulfilling life. Art enriches the soul and brings beauty to life. Here is what Sir Philip Pullman (ALMA, n.d.), award-winning British novelist, says:

Children need art and stories and poems and music as much as they need love and food and fresh air and play. If you don’t give a child food, the damage quickly becomes visible. If you don’t let a child have fresh air and play, the damage is also visible, but not so quickly. If you don’t give a child love, the damage might not be seen for some years, but it’s permanent.

But if you don’t give a child art and stories and poems and music, the damage is not so easy to see. It’s there, though.… That hunger exists in many children, and often it is never satisfied because it has never been awakened. Many children in every part of the world are starved for something that feeds and nourishes their soul in a way that nothing else ever could or ever would.

Beyond the cultural value art brings to children’s lives, it also serves a major educational and therapeutic value. Children communicate through their artwork, music, dance, and movement. For many children, it is easier to express their emotions through these avenues than it is through talking. For children with a history of trauma who may not comprehend what has happened to them and are not always aware of what their feelings are—let alone why they feel the way they do—the arts may be the best way of giving them a voice. Engaging in arts also offers restorative powers for children who have experienced trauma (Sorrels 2015). The rhythm of music, for instance, can help organize a brain that is disorganized (Baker 2007).

The arts are a prime outlet for communicating about the trauma. Drawing, painting, modeling with clay, dancing, singing, and moving to music offer a path to survival and recovery. Listen to and observe children as they create and work through their emotions in art; let the information you gain guide your next steps.

Provide children materials, space, and time for creating, moving, and expressing themselves each day, not just for special projects. Art, music, and dance should also be taken outdoors. Singing with children at arrival and departure times or during cleanup or transitions becomes a ritual that gives children a sense of belonging and security.

Principle 10: Look Beyond Children’s Traumas and Celebrate the Joys in Life

Throughout this book there is a global theme: Your knowledge, skills, and dedication will help children experiencing trauma to heal and flourish. It’s easy to get caught up in the many challenges that must be faced to help children get to the point where they will heal.

Healing, though, is just part of the goal. What about the flourishing part? Children who have been traumatized are children first, and they are due the same aspirations and high expectations that every child in your program is due. Helping children flourish means taking a deep breath and refocusing on the lightness and laughter that is, happily, also a part of teaching.

Help children find activities and experiences that let them feel good about themselves and their place in the world. If a child loves music, use that as a forum for the child to shine. The patterning in music can be used as a springboard for developing math skills. If a child is good at throwing and catching balls, incorporate physical activity as a part of learning. Have them make up part of a continuing story as the ball is thrown and caught. Let their strengths and interests guide the presentation of content.

Encourage children to be creative and silly and to delight in a belly laugh when something humorous happens. As noted previously, one of the chief goals of a healing-centered program is that children be able to share in the normalcy of childhood. This means that all children deserve high-quality programming, nurturing interactions, a warm atmosphere, and an environment where they can be curious and explore, experiment, and discover with competence and confidence.

You also want to help children look beyond themselves and develop empathy and kindness toward others. Consider having a gratitude box prominently displayed in your room (Colker & Koralek 2019). Each day have the children think of something good that happened for which they are grateful and would like to share with others. A gratitude memory can be anything from “My teacher picked me to help get out the cots for rest time” to “They served chicken fingers for lunch” to “I made a pretty collage.” At a designated time, help the children write their memories on index cards that can be inserted in the gratitude box. The children can illustrate the cards and sign them or leave them unsigned. Don’t forget to write and insert your own gratitude card. At a morning meeting perhaps once a week, randomly pick out a card from the gratitude box and read it aloud to the group. If the card has been signed, have the author—even if it should be you—tell the group how this memory made them feel. If unsigned, have the group talk about that gratitude memory together.

Taking the time to reflect on and express gratitude not only makes children kinder but also counteracts the trauma-related effects of stress and depression in the one who is grateful (Colker & Koralek 2019; Seligman 2005). By looking beyond themselves, children feel better.

Activities like this will also make children who have experienced trauma feel both like they are a part of the group and that they are moving beyond the trauma into a world where their trauma no longer defines who they are and what they can do. You want children to be able to embrace joy and feel that the world can be a good and loving place.

Principle 11: Remember that You Don’t Have to Have All the Answers

The most knowledgeable and confident people know their limitations and willingly admit to the need to learn more. You are not expected to know everything. If you don’t have the training or experience to know how best to respond, seek advice. This is nothing to chastise yourself for. To the contrary, you should be proud of yourself for doing what is best for children.

If you don’t know how to handle a child’s challenging behavior or how to prevent other children from shunning a traumatized child who is being obnoxious to them, ask your administrator or a counselor or specialist for guidance and support. They can help strategize how to help a child who bites or to stop bullying in its tracks.

Likewise, don’t feel you have to be certain before referring a child to a mental health, special education, or counseling professional for evaluation. Together with the specialist and the child’s family, decide if the child could benefit from some type of intervention.

Depending on the need, there will be many times you will want to consult with the child’s family or guardians. If it is a policy question, check with your administrator. Your colleagues can also offer helpful information. Often you need to check with specialists. If the child is seeing a therapist, that person may have the answer you are seeking, although be prepared if this person cannot answer anything personal about the child due to doctor–patient confidentiality. If you are part of a school system, there is often a psychologist or special educator on staff who can assist you.

The point is that you are not alone during any of this. You are in the front line, but you are also part of a trained and prepared program and community that are there to support you—just as you support children. With patience and dedication, you can turn children’s fears and insecurities around.

A Path Forward

Children with a trauma history need and deserve to be viewed, educated, and treated as children first, not as trauma victims. This means that they too can share in the educational future you envision for the children in your program. By using the guiding principles presented in this chapter, you can steer children with a traumatic past toward a present and future with promise. The next few chapters offer further guidance on how you might best do this.