CHAPTER 27

The MCT Ketogenic Diet

This chapter was written by Elizabeth Neal, RD, PhD, who works as a dietitian for Matthews Friends in the United Kingdom and has both clinical and research experience with using the MCT diet.

By the mid-20th century, when the classic ketogenic diet was falling out of favor because of availability of new anticonvulsants and a feeling that large amounts of fat were unpalatable, Dr. Peter Huttenlocher of the University of Chicago set out to invent a new and improved form of the ketogenic diet. He believed that the ketogenic diet was an effective treatment that more families would try—and benefit from—if it were formulated with foods more closely approximating a normal diet. Dr. Huttenlocher and his group replaced some of the long-chain fat in the classic ketogenic diet—that is, fat from foods such as butter, oils, cream, and mayonnaise—with an alternative fat source with a shorter carbon chain length. This medium chain fat, otherwise known as medium chain triglyceride (MCT), is absorbed more efficiently than long chain fat, is carried directly to the liver in the portal blood, and does not require carnitine to facilitate transport into cell mitochondria for oxidation. Because of these metabolic differences, MCT will yield more ketones per kilocalorie of energy than its long-chain counterparts. This increased ketogenic potential means less total fat is needed in the MCT diet. Whereas the classical 4:1 ratio ketogenic diet provides 90% of energy from fat, the MCT ketogenic diet typically provides 70% to 75% of energy from fat (both MCT and long chain), allowing more protein and carbohydrate foods to be included. This increased carbohydrate allowance makes the MCT diet a useful option for individuals who are unable to tolerate the more restricted carbohydrate intake in other ketogenic therapies. Recent evidence from laboratory studies also indicates that MCT may additionally have a direct anticonvulsant action that is specific to medium-chain fatty acids of a particular chain length. Further research into this exciting area is ongoing.

Calculation of the MCT diet is not based on the ketogenic ratio but instead looks at the percentage of dietary energy that is provided by MCT. The original MCT diet provided 60% energy from MCT; the remaining 40% included 10% energy from protein, 15% to 19% energy from carbohydrate, and 11% to 15% from long-chain fat. However, this amount of MCT caused gastrointestinal discomfort in some children, including abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting. For this reason, in 1989 Dr. Ruby Schwartz and her colleagues suggested using a modified MCT diet, which reduced the energy from MCT to 30% of total and added an extra 30% of energy from long-chain fat. In many children, this lower amount of MCT may not be enough to ensure adequate ketosis for optimal seizure control, and in practice a starting MCT level of 40% to 50% energy is likely to provide the optimal balance between gastrointestinal tolerance and good ketosis. This can then be increased (or decreased) as necessary during fine-tuning. Christiana Liu and her colleagues in Toronto published a paper in 2013 on their extensive experience of using the MCT ketogenic diet. They report good tolerance of diets with 40% to over 70% energy from MCT, with a generous carbohydrate allowance. However, they highlight the importance of close monitoring of gastrointestinal symptoms, especially during the initiation of the diet where problems can occur if MCT is introduced too quickly.

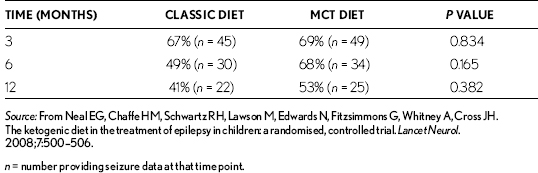

Schwartz and her group in 1989 also compared the clinical and metabolic effects of the MCT ketogenic diet, both traditional (60% MCT) and modified (30% MCT), with the classic 4:1 ketogenic diet. They found all three diets equally effective in controlling seizures, but compliance and palatability were better with the classic ketogenic diet. However, in this study children were not randomly allocated to one of the diets, leaving it open to possibility of bias. The question of differences in efficacy and tolerability between the classic and MCT ketogenic diets was further examined at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, in a randomized trial of 145 children with intractable epilepsy, the results of which were reported in 2009. Children were randomized to receive a classic or MCT ketogenic diet and seizure frequency was assessed after 3, 6, and 12 months. Data were available for analysis from 94 children: 45 on the classic diet and 49 on the MCT diet. Table 27.1 shows results for percentage of baseline seizure frequency between the two groups after 3, 6, and 12 months. Although the mean value was lower in the classic group after 6 and 12 months, these differences were not statistically significant at any of the times (the P value is greater than .05 at 3, 6, and 12 months). There were also no significant differences in numbers achieving greater than 50% or 90% seizure reduction. Serum ketone levels (acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate) at three and six months were significantly higher in children on the classic diet. There were no significant differences in tolerability except increased reports in the classic diet group’s of lack of energy after 3 months and vomiting after 12 months. This study concluded that both the classic and MCT ketogenic diets have their place in the treatment of childhood epilepsy.

So how does the MCT diet work in practice? The MCT is given as a commercially available MCT oil or emulsion. At present there are two emulsions: 50% MCT (Liquigen®, Nutricia) or 20% MCT (Betaquik®, Vitaflo), both of which are available by prescription in the United Kingdom and the United States. The amount of MCT has to be calculated into the diet just as for any other fat and should be divided up over the day and included in all meals and snacks; the amount will be specified in the diet prescription provided by the dietician. MCT emulsions can be mixed with milk as a drink (best with skimmed or semi–skimmed milk as full-fat milk causes the mixture to thicken excessively); they can also be added to foods such as soups and mashed potato, or used in recipes, ranging from sugar-free jellies, sauces, and baking. MCT oil also works well in meal preparation and baking. Recipes for meals and snacks are available from Matthew’s Friends (www.matthewsfriends.org). MCT has a low flashpoint, so be cautious when frying, and keep the temperature fairly low!

TABLE 27.1

Mean Percentage of Baseline Seizure Numbers at 3, 6, and 12 Months in Classic and MCT Diet Groups

As the MCT ketogenic diet allows a wider variety of antiketogenic foods, portions of protein foods are more generous than with the classic diet, as are the allowed amounts of fruits and vegetables. Small amounts of higher carbohydrate foods, such as milk, bread, potatoes, and cereals, can also be calculated into the daily allowance. Sweet and sugary foods are not allowed and low-glycemic index carbohydrate choices are encouraged. As with the classic diet, food must be weighed accurately and energy intake is controlled. Although the prescription can be implemented using exact recipes, many centers will prefer food exchange lists because of the more generous amounts of carbohydrate and protein. The use of separate carbohydrate, protein, and fat exchanges is recommended because this allows an even macronutrient distribution over the meals and snacks. Individual requirements for micronutrients must always be considered with additional vitamin, mineral, and trace element supplementation. The prescribed diet must also meet essential fatty acid requirements.

The MCT diet can be provided as a tube feed if necessary but there is no complete product available as there is for the classic diet, so the prescription and preparation of such a feed will be more complicated; use of a classic ketogenic diet feed product will be preferable.

On commencing the MCT diet, the MCT oil or emulsion needs to be introduced much more slowly than long-chain fat (over about 5–10 days), as it may cause abdominal discomfort, vomiting, or diarrhea if introduced rapidly. During this introduction period the rest of the diet can be given as prescribed, but an extra meal may be needed to make up the energy while using less MCT. Once on the full diet, it must be followed just as strictly as the classic diet. Fine-tuning is usually needed to maximize benefit and tolerance. This is done by increasing or decreasing the MCT dose; the amount of long-chain fat can be adjusted to keep the same total energy from fat in the diet. If a higher level of ketosis is desired and an increased amount of MCT is not tolerated, the amount of carbohydrate in the diet can be reduced and long-chain fat increased to balance overall energy provision.

Discontinuing the MCT diet should be done in a stepwise process. The MCT is slowly reduced and the protein and carbohydrate increased. However if the MCT diet works well, as with other ketogenic therapies, it is usually continued for at least 2 years.

In oil or emulsion form, MCT can also be used as a supplement to the classic ketogenic diet, both to increase ketosis and to help alleviate constipation. Swapping some of the fat allowance for a small dose of MCT can soften the stools and, in limited amounts, is usually well tolerated. In a similar way, MCT is increasingly being used to supplement the modified Atkins diet to boost ketone levels.