Over time, we have learnt that it is most productive if the trainees attend the first meeting of the PPD module during their introductory week on the course—preferably on the first day, as previously indicated. The small groups now meet for a total of nine hours each during that first week in order to create an integrated and mutually supportive trainee group as quickly as possible.

In both the large and the small groups, the leader(s) introduce the module, engage the participants, arid aim to create an atmosphere of trust, where confidences will be respected; the leader(s) also disclose relevant personal and professional material to encourage this process and to reduce the gap between group member and leader. Because humour is such a tremendous asset in helping people to relax and learn without loss of face, an early aim is to create an atmosphere of playful seriousness.

Throughout the module, the leader deliberately suggests that trainees work in a variety of combinations: sometimes in pairs, for more intimate disclosure; sometimes as a whole group, in order to disseminate a wider variety of ideas; sometimes in their specific sub-groups, such as the supervision groups, in order to confirm their identity. In the pairing exercises, trainees are encouraged to choose a partner whom they know least well, so that the group becomes more cohesive over time. Balking at taking part in exercises is rare, and I usually respond to such reluctance by considering the expectations that we have that clients divulge their all in therapy, and why we think that it is important, and finally link this with the group's ideas about helping other trainees become more involved.

The first exercise takes place at the first group meeting of the module, after the leaders have introduced themselves.

Timing 20 minutes.

Comment The repetition helps everyone to make connections between names and faces and encourages a sense of mutual recognition. It is the beginning of a process of group cohesion. As the challenge to remember gets harder, some of those who have already had their turn may become very protective and start to prompt those who are struggling, whilst others appear more competitive. These responses often provide early and useful indicators of the ways in which certain group members respond to group situations. It is the beginning of getting to know the participants.

Caveat I would recommend the use of this exercise for up to—but not more than—30 people. Remember:

Professional pointers The way in which people respond to names unfamiliar to them, especially those from other languages, can become a learning exercise in itself. When the naming game has been completed, the group is encouraged to discuss this issue in terms of their own experiences, coping with persistent mispronunciation, and how in practice they deal with clients who come from other cultures and have names that are hard to recognize and difficult to remember.

This can best be done in pairs, because it gives each trainee an opportunity to get to know another individual before having to speak in the group.

Timing Approximately 20 minutes.

Comment Allow more time than you might think necessary, as this exercise tends to generate a lot of comment and disclosure of family attitudes and relationships, as well as patterns over generations. Sometimes it can lead to unexpected associations and attributions ascribed to names (Bennett & Zilbach, 1989).

To encourage an open and more equal atmosphere, I related my own experience of being called Judith, which I described as implying having to be good, sitting up straight, and being utterly conventional. Failure to obtain my "posture girdle" at school finally convinced me that Judith, despite the exciting biblical association with Holofernes, was clearly not the name for me. Paradoxically, I only felt entitled to use the less formal name Judy when I became professionally established and felt that I had earned the choice.

Caveat It is important to move from the pair back into the whole group so as to build up a process of wider group connections. In small groups, feedback can be shared generally; in larger groups, it can be helpful to split into sub-groups of four for further discussion for a short time, before asking for comments from the whole group. This gives more trainees an opportunity to take an active part in the discussions.

Professional pointers Clarification with clients about how they would like to be addressed is not only a mark of respect but can also produce important information. A discussion of the significance of names and connections between family members who have the same name is an extremely useful way to open up discussion in therapy. It often also provides data about cultural practice—for example, there are those cultures in which you cannot name a child after a family member who is still alive, whereas in others a child may be given the name of a respected or loved living relative.

After each set of questions, allow time for the pairs to do their talking for 5-10 minutes at each of the indicated pauses.

If you do become qualified, what will you have proved and to whom?

(pause)

Do you think that being a family therapist is a way of finding out more about yourself and your family, or a way of learning how to avoid finding out more?

(pause)

How do these opinions affect you?

(pause)

Timing Approximately 45 minutes.

Comment Useful connections may be drawn between therapists' and clients' reflections on corrective or replicative family scripts.

Caveat If trainees are feeling anxious, they may give rather glib responses initially; if given adequate time to think about the issues, however, it will be a useful exercise at the start of their course.

Professional pointer Trainees who focus on pathology or go "looking for trouble" in their clinical work may also lose sight of strengths in their own and their clients' families.

This exercise has proved most effective when used on the first day of the PPD module, i.e. before the group members get to know each other. It works equally well with small and very large groups.

(At this stage, the four are relieved to return to their seats and gratefully merge with the group.)

Timing 35 minutes.

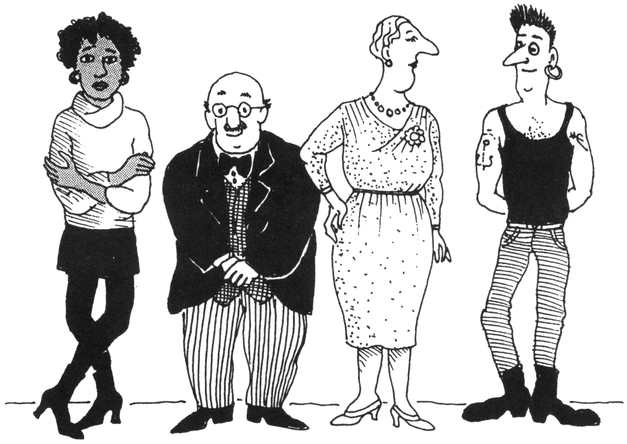

Comment This is a very powerful exercise, pushing participants to acknowledge their own biases and to consider how they in turn may be perceived by others. In my experience, most trainees make their final selection on the basis of their first impressions, although occasionally a few change their original choice when the therapists start talking and may become more animated and mobile. The content as well as the style of their interaction with others can prove either reassuring or a limitation.

Caveats

(a) Clearly, at this early stage in the first meeting of the module, trainees are still very uncertain and anxious about being exposed. If those selected demur, the leader usually makes the point that this is a similar situation to that regularly experienced by our clients, who are constantly required to expose themselves—and their dilemmas—in front of strangers. Some genuine explanation that the leader needs some help, and that it won't last too long, usually does the trick. Making it overt that you are seeking difference may make it easier too.

(b) It may be awkward selecting people on the basis of discernible difference such as race, size, or style of dress, but being "protective" and ignoring difference is poor modelling and is not helpful if the aim is to be more aware of the wide range of clients' views.

(c) It is important to allow adequate discussion time for people to make connections between what they are looking for in a therapist and what they themselves might represent to their clients, and how to deal with any discrepancy!

(d) There may be a temptation to rush the process of the exercise to save the four potential therapists from possible discomfort or embarrassment, but succumbing and galloping on will give a very mixed message about the importance of the exercise.

Professional pointer Therapists can forget how uncomfortable and "on show" clients can feel through having to expose their difficulties in front of strangers, being videoed, and so forth. It is hard to remain sensitive to the novelty of this experience for the clients, especially when as a therapist you are dealing with families on a daily basis. Hopefully, this exercise brings trainees in touch with some of the discomfort experienced by clients.

The purpose of the exercise is to increase the trainees' awareness of how they may impact on others—and to become more selfaware of how their appearance, age, race, gender and physical presentation may impact on clients.

The exercise could be further developed into a discussion about which differences could be comfortably discussed and how the trainees might deal with their own and their clients' disappointments or prejudices.

This exercise is often considered by trainees to have made the most impact in the first few meetings of the PPD module. The exercise was designed to try to address the issue raised by Flaskas and Perlesz (1996) that since family therapists are not required to have any personal therapy, they may not have experience of the client position.

I In the first or second meeting,

Timing 1¼ hours.

Comment As you can imagine, the experience makes a forceful impact. The purpose of this exercise is to emphasize how anxiety-provoking a visit to an institution can be and how people feel less respected when they are kept waiting and are unaware of what to expect. In practice it is not unusual for therapists to continue with their supervision group or team discussions even though they know that the family has arrived and is waiting. Taking part in this exercise and knowing what it feels like to be ignored and kept waiting may discourage this aspect of disrespectful practice.

"Group members as 'family' in waiting-room"

What is somewhat surprising is the degree to which the trainees, who are "only" role-playing, nonetheless find this such an incredibly powerful and uncomfortable experience. I have wondered whether this might be because in this situation they are forced to think of themselves as being on the same continuum as clients, rather than being able to hide behind their professional status. However, I remain uncertain as to whether the non-role players found the exercise equally as potent.

Caveats

(a) Be on good terms with your administrative staff, and remember to make them part of the plan and to thank them afterwards.

(b) Encourage the observers in the group to get feedback from the "role-players" first before a more general discussion.

Professional Pointer It is often difficult for trainers to convey adequately the essential message that clients and therapists inhabit a similar emotional continuum; therefore, these early exercises focus on attempting to bridge the artificial dichotomy between "them and us"—that is, the professionals and their clients.

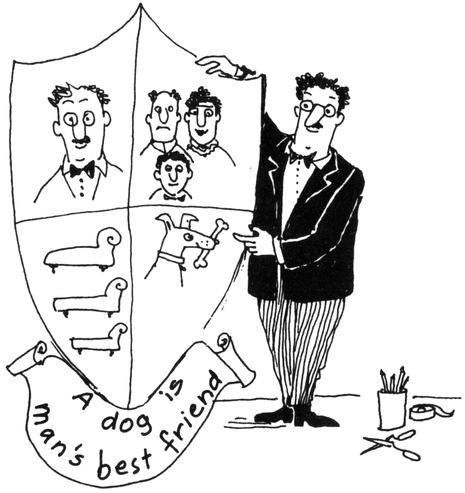

Timing V/i hours (45 minutes for the drawing of the shields, and the remainder for setting the task and showing and discussing the shields).

Comment This is a powerful tool for encouraging people to think about themselves in a simple way in which symbols may be more immediate and significant than words. This exercise also demonstrates a technique that can be used equally well with clients. By doing the exercise themselves, the trainees are not only involved in a personal experience, but are also learning a new clinical intervention. As can be seen, the individual has to consider himself in relation to four major perspectives. I personally find this exercise quite a challenge: by specifying these four significant areas, it is difficult to avoid thinking about major aspects of the self. Hopefully, trainees doing this exercise will be encouraged to see their clients subsequently as less unidimensional than they might appear in therapy.

"Personal shield"

It is helpful to remind participants that, over time, what they might draw on their shields will change, depending on their particular circumstances and mood.

Even in large groups, where there will not be much time for looking at everyone's shield in detail, it is important to acknowledge all their efforts and ask everyone to hold up their drawings, in order to show the variety of drawings and symbols. Some people appear much more secretive than others about their shields and will draw the most obfuscatory symbols, whilst others actively enjoy the process of both drawing and explaining theirs. In small groups all participants are encouraged to show and tell.

One very courteous mature trainee, an established academic from overseas, filled her shield with images of serving others. Her motto read "Always consider others first". Feeling emboldened by the trainee's enthusiasm in the group, I wondered whether this was really the motto she had in mind and so asked the trainee what else she might have written instead, pointing out that she could experiment with being uncensored and free to say anything at all. The trainee looked up and then, with great daring, wrote "Oh, fuck it" on her shield. It brought the house down!

Caveats

(a) Some trainees dash through their drawing, but this should not induce the group leader to rush the process; they often come back to their shields and then get more involved with them, especially when they observe their colleagues continuing to work on theirs. If people respond by saying that they cannot draw, clarify that it is not about art but about what can be communicated in another medium. Designing something totally enigmatic or producing an absolutely minimalist drawing can make a considerable impact on the group and can be constructively linked with professional skills, such as how to deal with a family in therapy who opt not to do a task or do it in a minimal way.

(b) Just as it is important to avoid becoming symmetrical or critical of clients who do not appear to take advantage of their therapist's interventions, the same is true of leaders in relation to trainees.

Professional pointer As commented above, this is a new technique for exploring the creativity of clients and trainees; one in which non-participation is as informative as activity. This exercise is particularly useful in clinical practice when working systemically with an individual or a couple.

"Sharing the cake"

Timing Including explanations and discussion, a minimum of 35 minutes is needed. Allow 15-20 minutes to stay with the task itself.

Comment The idea of symbolizing slices of a cake to depict the amount of space allocated to each of an individual's roles was introduced in 1995 by C. P. Cowan and P. A. Cowan during a workshop presentation on becoming a family.

This is an effective way of reducing complicated issues to a manageable proportion in the context of a group. Initially it seems simple, but it can have a powerful effect, leading to trainees having to consider their own situation, how they have organized their lives, and whether this is what they want.

This is one of those exercises that some people may try to rush through without thinking about the implications; however, by suggesting that those who finish quickly wait while the others complete their cakes, it is possible to establish a more serious atmosphere and provide further time for contemplation.

Caveat Ensure that there are paper and pens available.

Sculpting (see Duhl et al., 1973) is a three-dimensional representational method of communicating a personal experience; it can make an immediate and powerful emotional impact not only on the sculptor, but also on those taking part in the sculpt and those observing the process. Using this technique in the early meetings quickly leads to mutual sympathy and respect as well as to group cohesiveness. The technique is also used to look at systems such as trainees' agencies and other wider networks.

Consistently over the years, trainees have reported that they have found sculpting to be one of the most effective and moving exercises, one that provides a snapshot, capturing a moment imprinted on the memory. Specific examples of participants' sculpts have not been included here, out of respect for confidentiality.

The technique is taught by the leader describing the purpose and method of sculpting, then modelling the process; finally, trainees take it in turn to guide each other through their sculpts, so that the group leader need not remain so central. Great store is placed on attention to details of closeness and distance between family members, and on specific postures and facial expressions. The whole process unwinds slowly, allowing the sculptor to get in touch emotionally with the experience. As little as possible is said, in order to avoid disturbing the atmosphere; the leader or guide stays near the sculptor to offer support and may touch his arm in encouragement.

Although a great deal of emotion may be raised in these sculpts, they should be dealt with in a supportive way by the group and contained by the group leader, rather than becoming the focus of therapeutic interventions. The aim is to model building on strengths and the widening of perspectives rather than hunting for pathology. Where a person is particularly affected by his sculpt, time is allowed to help the trainee express feelings and then move on to linking the past and present. Hopefully this process is therapeutic, albeit not therapy per se.

Sculpting in the context of the small groups is usually started during the block week at the beginning of the course and completed within the subsequent two meetings.

Timing 45 minutes per person to include sculpting and discussion for each person, plus a brief break of at least 5 minutes between each one.

Comment Sculpting serves as an initiation rite, in which each participant offers personal material as a rite de passage to becoming a member of the group. Trainees virtually always choose to sculpt a traumatic episode from their past, possibly as a way of making the most of an opportunity to explore and find different meanings in such an episode. They have often remarked on the powerful effect of being in someone else's sculpt and experiencing a situation from the sculptor's viewpoint.

Caveats

(a) The exercise as presented here can only be used with small groups, since each person needs at least 30 minutes.

(b) These personal sculpts are often incredibly moving, and intensify an experience, so it is important to be respectful and allow the sculptors adequate time to set them up, with pauses for thought, and to re-experience the feelings associated with them.

(c) It is essential to ensure that all the trainees will have done their sculpts within as short a period of time as possible. Too long a delay may leave some trainees feeling exposed if they have already sculpted their family, and it can create unnecessary anxiety for those still to do their sculpts.

(d) In the small group, the intensity of the sculpting experience is such that subsequent sessions can feel like an awkward change down from fourth to second gear. A few trainees have been disappointed at the subsequent lessening of that heightened emotional level and personal focus.

In other instances, sculpting has been used to trouble-shoot—for example, on occasions in the small groups, to find out more about conflicts and alliances within a group.

Timing 35 minutes.

Comment It is important to specify that the sculptor was merely presenting his own view, rather than "how it is". If no one is prepared to do this, two people can be asked to place two or three others around them and then ask these two mini-groups to place themselves in juxtaposition to each other. Finally, the remaining trainees are invited to put themselves into the sculpt. It may prove confusing, but it will demonstrate alliances and distance between the participants.

Caveat Stage C can lead to an idealized harmonious group sculpt, avoiding making any conflicts overt. However, the discussion at the end of the exercise often leads to helpful expressions of difference as trainees describe their preferred, and often different, outcomes.

Professional pointer This is one example of dealing with the concept of "speaking the unspeakable", which the trainees are encouraged to pursue—either verbally or metaphorically.

As the following example demonstrates, sculpting can also be useful as an unplanned and spontaneous technique;

Two trainees wanted to air their differences in the group; after each had described his view of the disagreement and reached an impasse, a third was asked to help each of them sculpt firstly how the situation had arisen and secondly how it looked currently. The two were then asked to demonstrate in turn how they would like their relationship to look. The remainder of the group encouraged them to demonstrate, with a moving sculpt, the steps that would need to be taken to get into this desired relationship. The original pair were then left to discuss the exercise in private while the remainder of the trainees discussed other splits and alliances in the group.

Professional pointers Learning to sculpt is a technique that can be directly used with clients and when consulting to networks. It is particularly useful with families in which problems have become intellectualized and stuck.

Because of time limitations, sculpting in large groups must be done in sub-groups rather than by each individual trainee. For example, sculpting was used to demonstrate the prevailing mood within the supervision groups and to activate creativity and humour to deal with participants' anxieties.

Leaders of the large groups always tried to find connections between issues that the group members raised and the planned format; when at times this was not possible, we would adjust to their needs, discussing this shift of focus with them.

On one occasion, the group leaders had planned to consider the different ways in which trainees might introduce new and possibly challenging ideas to their clients; the intention was to link this to the ways in which they themselves had learned to cope with change in their own family of origin. However, following our usual opening question—"How are things—what's happening?"—we sensed an extremely high level of anxiety in the group. We discussed this openly in front of the trainees and agreed to change tack. We decided to use the situation to try to normalize some of the participants' worries, to encourage them to learn from each other, and to explore different and creative ways with which they, in turn, could help their clients deal with fears. The emphasis had shifted, from a direct focus on the introduction of change, to how to ventilate anxiety about feeling deskilled on a demanding, challenging course.

Timing Approximately 1 hour, depending on the number of supervision groups: at least 15 minutes is needed for initial discussion and preparation of the presentations, and 5 minutes for each to be presented.

Comment The result was both hilarious and inventive. One group mimed being airline passengers in flight without a pilot, but with a rather uncertain, tentative stewardess attempting to be in control as the plane took off for what turned out to be a very bumpy journey indeed. The relief when they landed was almost palpable. Another used clipboards and pens to devise a colourful board game based on snakes and ladders, with players making darts ahead only to be apparently arbitrarily shunted back to the starting line. Another group precariously balanced various up-ended tables and chairs into a pyramid, with the four members of the supervision group scrambling—and alternatively pushing, shoving, and even occasionally supporting each other—to get to the top. Yet another group was desperately trying to row their boat down the stream, as one trainee kept threatening their survival by rocking the boat and finally falling out. The others resisted the temptation to leave him in the water, and slowly hauled him aboard—he was last seen waving, not drowning! In a graphic demonstration of parallel training and domestic pressures, one trainee was first seen being circled by his three colleagues, each indicating that he should be doing something different, and then was seen returning home where his wife and two children each started pulling him in different directions.

Professional pointer Whilst metaphor is well established as an integral part of clinical practice, the use of play to make your point is less so. I believe that too often the therapist sets the tone of interviews by her own serious demeanour, which may not take into account the family's natural style, spontaneity, and imagination, all of which could be used in problem-solving.

Exercises like these were successfully used to encourage group cohesion, to share personal information, and to encourage the use of humour and creativity to dispel some anxieties.