ABOVE: The stone wall that encloses this side patio was specifically designed to display sculpture at eye level.

ABOVE: The stone wall that encloses this side patio was specifically designed to display sculpture at eye level.

It is not easy to define June LaCombe in simple terms. She is an accomplished gardener and a dedicated artist, but she is also a very successful curator, a serious art collector, a lifelong naturalist, a student, an educator, and an advocate. She has so seamlessly integrated these many aspects of her life that, in every endeavor, she is never just one but all in differing proportions. When she speaks of the inseparability of one aspect from the others, she communicates in such a thoughtful manner that her quiet demeanor nearly belies the deep passion she feels for what she has created, and continues to create—a life built on exploring and challenging the boundaries between the ideas of “art” and “garden.”

The back roads of Maine are full of surprising treasures, and June LaCombe’s gardens are a wondrous example. Hawk Ridge Farm, at the end of a long gravel road, is the home and studio she shares with her husband, Bill, and the center of her creative expression. Purchased thirty years ago, this working farm had a fine core of old maples and ancient pear and ash trees. Today the meticulously restored and expanded house is entirely surrounded by gardens, fields, and woodlands that June has designed specifically to showcase works of art from her own extensive collection as well as from the artists she represents. In 1996 she curated her first exhibition of sculpture in this environment as a way to “give voice to place.” This concept, originally expressed by earth artist, art historian, and photographer James Pierce, resonated so strongly with June that she has been exploring the relationship between sculpture and setting ever since. “Sculpture, like the landscape, has a resonant energy. When, through careful siting, it becomes the focus of a place, you start to see both with greater acuity.”

ABOVE: On a sunny ledge in June’s office, peony blossoms fill a carved stone urn by Stephen Parmley.

From the handsome, light-filled addition where June hosts art collectors’ groups from around the country, sets of French doors open to a long brick patio backed by a wall of dry-stacked native stone. Lined with weathered cedar benches and large, simple urns, the three-foot wall is specifically designed to exhibit smaller sculptures at eye level. A precisely balanced stone piece by John BonSignore and an elegant marble by Constance Rush reside among the double pink peonies, irises, lady’s mantle, rosy spirea, and silver artemisia that tumble over the edges of the densely planted bed. The permanency of the sculpted materials, backed by a deep green screen of late-blooming Japanese lilacs, enhances and is enhanced by the shifting colors and textures of the surrounding flowers and foliage.

Gary Haven Smith’s White Line is tucked among the foliage in a shaded spot.

Curving around the back of the house are large specimens of honeysuckle, native aster, witch hazel, and a flowering almond shrub that June has pruned into tree form—its fragrant creamy peach flowers covered with bees each spring. The yard is edged with a mix of mature shrubs that define the space: highbush cranberry (Viburnum trilobum), autumn olive, quince, double-file viburnum, rose of Sharon, and shadbush. A hedge of forsythia, started with cuttings from June’s grandmother, balances a row of sweet-scented mock orange, her grandfather’s favorite.

Toward the house, the gently sloping lawn leads down to a low semicircular stone wall, which wraps around a giant pear tree before fading into the ground at the far end. This earthwork, along with a mirroring pair of paisley-shaped beds that bloom with cream-colored tulips in spring and white impatiens in summer, was created specifically for the purpose of presenting the tree and was inspired by the work of early earth artists. June has studied the art and artists of this still-evolving movement for many years and in 2004 completed doctoral studies at Antioch New England in a self-designed program researching the integration of environmental art into the field of environmental studies. She believes that the work of artists such as Lynne Hull, Agnes Denes, and Ana Mendieta can teach us as much about our relationship with the environment as can scientific study. “The arts engage the emotions, and that may be the spark needed to stimulate action,” she says.

ABOVE: Works in stone of varying colors and textures blend and contrast with the hardscape and plantings throughout the property.

“Sculpture, like the landscape, has a resonant energy.”

At the edge of the lawn, a rustic gate opens to a stone path that wends its way down a fern- and hosta-covered slope under a canopy of shade trees. Fittingly nestled in the vegetation is a striking set of white terra-cotta Fiddleheads by sculptor Sharon Town-shend. The path leads to a discreet swimming pool, lined black in order to more naturally resemble a pond. The surrounding brick patio includes a small post-and-beam pool house, its flush board siding covered in lattice and climbing vines. At the far end of the pool, a large flat-topped rock serves as a diving platform. Whimsical, brilliantly colored metal chairs by Melita Westerlund offer a place to sit and study the wildlife that frequents the fields beyond.

In addition to creating a venue for sculpture, June’s reverence for the land inspires a stewardship that includes organic gardening practices and the creation and preservation of wildlife habitat. She also raises peacocks and a small flock of chickens, which are let loose in the perennial beds each spring so they can gently ‘till’ the newly thawed soil. In wide fields that parallel the gardens, her horses canter and frisk in a rotating landscape of fresh clover. Indigo buntings, attracted to movement and sound, frequent the stone fountain just outside June’s office window. In their dedication to resource preservaton, June and Bill have replaced their inefficient windows, added insulation in the original parts of the house, and installed a wood-pellet furnace, which uses the waste wood so abundant in this forested state. They use an old-fashioned clothesline. They hope their home can become a model for sustainable life practices as well as a living gallery.

June’s senses are acute and tuned into this rich environment, and she is particularly attracted to sculptors who share her sensibilities: those who work with earth’s elements—particularly stone and wood—and who listen to the materials in order to create work that goes beyond what it might represent. Many of pieces she shows bear evidence of the material in its raw form, before the artist’s hand touched it. In selecting and siting this work on her land or elsewhere, she hopes to expose the viewer to a different way of interacting with the natural world, to engage with a material or a place without dominating it.

ABOVE: Chairs by Melita Westerlund and Eros Snake Eros Woman by Squidge Liljeblad Davis are shown by the poolhouse.

Sculpture in the Landscape

ABOVE: Fiddleheads by Sharon Townshend

ABOVE: Daphne by Celeste Roberge

ABOVE: Landscape by Cabot Lyford

“My goal is to find the right piece of sculpture for the setting so that both will resonate in new ways. Sculpture can help us explore our relationship with our environment and give years of contemplative pleasure. There is a changing role for sculpture today. Sculpture holds a place in a garden or landscape, making us more aware of natural forces. It sets up a relationship with the land and enlivens a place. Sculpture can provide a focal point for a contemplative garden. A strong piece of sculpture will continue to reveal itself over time and celebrate the beauty of the material, the sensual appreciation of form, and its setting.”

–June LaCombe

Over the years June has sited sculpture in temporary exhibits on her property.

The opposite end of June’s property is divided into three distinct environments. At the far edge is a large field of tall meadow flowers that sway rhythmically in the gentle wind. Mown paths lead the way through clover, fragrant lady’s bedstraw, starflowers, vetch, milkweed, and blackberries. Along the far hill, June has planted a contour of lupines that have spread among the native dock, buttercups, daisies, and hawkweed. Placed throughout this field are a half-dozen large sculptures in stone, steel, and wood. Upon encountering them in this setting, one begins to experience the work in the way June intended. A set of large wire figures by Jean Noon seems poised to reveal the negative space between them. The bristled form of Celeste Roberge’s steel and copper Daphne reflects the structure of the wild vegetation around it. At night a plum tree at the edge of the field glows with pod-shaped orbs by light sculptor Pandora LaCasse. Under the tree a stone table provides an ideal midsummer setting for a feast of locally grown organic food; June regards cooking and sharing these meals as another component of the art process.

In the center of this vast front yard, June has designed and planted a garden that produces many of the organic vegetables, fruits, berries, and herbs she serves. The garden is laid out in a herringbone pattern of diagonal rows—increasing in length and planted according to crop need. Shorter rows toward the front of the bed are reserved for smaller crops of herbs; longer rows are for larger plantings of lettuces, peas trained on twig trellises, green onions, tomatoes, broccoli, and corn. Along the center path, the rows terminate in annual flower varieties. A grapevine rambles along a simple back fence and over an arbor that leads to the field. In the bright sunshine of the lawn, Andreas von Huene’s black granite Raven watches over a bed of rhubarb.

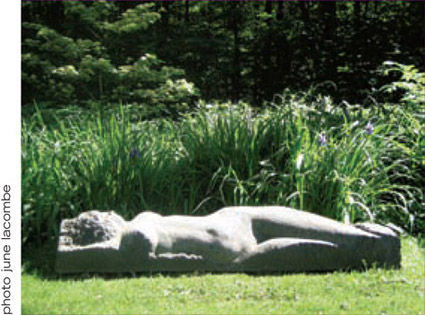

Across the yard, the road is edged with a meandering bed of pagoda dogwoods and hawthorns under towering stewartias. Groupings of old roses in a spicy, deep velvety pink are interplanted with lilies and dozens of varieties of antique columbine. Sprouting from seeds that June discovered around old house foundations while exploring the woods on horseback, the single, double, and triple columbines bloom purple, pink, and white each spring. Sited along the edge of the bed is a magnificent reclining nude, Landscape, by celebrated sculptor Cabot Lyford. Beyond the row of boulders, midday shade provides an ideal location for Gary Haven Smith’s granite and moss piece.

The soft curving forms of Seed of the Soul by Constance Rush and Leda and the Swan by Katie Bell are perfectly suited to the colors and textures in this bed of double pink peonies, both tall and creeping phlox, silvery artemesia, and irises.

June’s property includes several diverse growing environments. On the open southeast side of the house, George Sherwood’s kinetic sculpture, Curves of Life rotates slowly in the breezes that sweep across the wide lawn. The opposing pair of angled rows beyond are planted with herbs and vegetables to take advantage of the full sun. A grape arbor marks the entrance to the field of wildflowers and sculpture beyond.

The remaining lawn is left open but for a select few sculptures that balance this expanse of green in form, scale, and material. The opposing arms of George Sherwood’s kinetic Curves of Life rotate with the movement of the surrounding air. A pair of figurative gray granite abstracts by Roy Patterson glisten almost white in the strong sun. A line of mature maples that shades the house in the summer heat seem perfectly spaced to accommodate smaller works, such as one of Cat Schwenk’s Earth Books. Come fall the maples also provide shade for June as she creates her own artwork.

Considering June’s strong connection to place, it is not surprising that she often uses the raw materials around her as her medium. A decade ago when she and her husband returned from a ten-month residency in New Zealand, she saw her home with fresh eyes. She began to collect the big downy feathers shed by her peacocks, the vines from her grape arbor, iron ochre from the Indian paint pot mine in her own back woods, and shards of mica that littered the local landscape from an old feldspar quarry. With them she created a series of spheres that became touchstones for her journey back to these places she loves and the materials she had missed in her absence. Today she works primarily in clay because of its tactile nature. She remembers creating pinch pots as a child, and in her years as educational director of the Maine Audubon Society she often worked with groups of children digging clay from the riverbeds and experimenting with open-pit firing.

ABOVE: A trio of stone pieces by Jon BonSignore rise precariously from the tall grasses.

ABOVE: June sculpts leaves on a fall day.

Hers is a meditative art process; on brisk autumn days she will sit with the leaves swirling around her and absorb the beauty of this place, then work to express that beauty by hand-sculpting the twisting, curling leaves of clay. Her pieces are a form of note taking. When fired, the light, fragile bisque leaves evoke the essence of place.

June believes that living with art can be an important next step in our development as a society, nurturing a more contemplative, less consumptive lifestyle. With her own work, her exhibitions and patronage of sculpture by other artists, her continued study and frequent lectures on the integration of environment art and education, she strives to engage people in a process that is her source of constant exploration. Each year the sculpture she exhibits changes, but the meaning remains the same. “Celebrate the place, stimulate the senses, and understand with greater depth our connection with the earth.” June’s gardens are a living example of that connection, and her advocacy is strengthened by sharing the gardens with others. At Hawk Ridge Farm we see how sculpture in the living landscape can nurture the poetics of place, and the boundaries between art and life begin to blur.