Writing Lives

Some of the anxieties of a writer’s life brilliantly captured in these strip cartoons by the Detection Club’s own ‘Clewsey’.

![]()

The Writing Process

Reginald Hill

In composition I fall somewhere between Gray’s fantastic foppery and Trollope’s exact measure, but rather closer to the latter. I know there will be days when writing will be impossible, either physically or temperamentally, so on all other days, weekends and holidays included, I’m sitting at my desk by nine in the morning and there I stay till one, by which time I may have produced a couple of hundred or a couple of thousand words. Afternoons are for reading, research, deep thought, correspondence, plus the odd game of golf or the even odder bout of gardening.

I’m still very much a steam-age writer. I can’t type. I’ve tried and the noise distracts me, and besides, those regular little letters don’t reflect what’s going on in my mind anything like the spidery wanderings of black or blue lines of ink. I use a nylon-tipped pen, of a make which I’m not going to reveal unless they pay me. But I have used many a thousand of them and if I were ever the victim of an acid-bath murder and only the middle finger of my left hand remained, you could probably identify it by fitting one of these pens into the groove just above the top knuckle.

I generally start by reading through whatever I wrote the previous day, revising it in some small detail perhaps, and making marginal notes about any larger revision which I feel may be necessary. This is because I want to get on with the next bit and not finish the current session without any measurable progress in terms of length. Often I will have scribbled myself a note to remind me where I’m going next. Frequently these notes are totally illegible, and I have to press on without their help. Occasionally they are only half legible, and I am sure there have been times when I have inadvertently misled myself. I do, of course, have a broad idea of where a story is going, but there is a constant process of modification in the light of the opportunities that open up and the difficulties that become apparent as I write.

Changes, of course, are nearly always retroactive as well as anticipatory. To change a character or a relationship in mid-book requires the whole build-up to be altered. Frequently what seemed like a very small thing in the beginning involves something like a complete rewrite. At other times, having decided to modify a character, say, I discover as I work backward that this is not, after all, a sudden decision but something I’d been nudging myself toward for a long time, and relatively little needs changing in the earlier pages. I have on occasion even changed the identity of the murderer, which might seem so large a shift of direction as to be artistically disastrous. But always it has been because the character first designated in my mind has evolved into someone who could not have done the killing, whereas someone else has emerged who could. Of course the physical possibilities then have to be built in by an alteration of details of time and place throughout the story, but these are the mere furniture of a crime novel. I don’t think I’ve ever got them wrong yet, but I should much prefer to hear the complaint that my perpetrator was in the wrong place than that he was in the wrong personality.

Once a first draft is finished, I go through the whole book and do a detailed revision and reshaping, still in longhand. At this stage I find scissors and Sellotape come in very handy. Then the draft goes to the only person in the whole world who has a more-than-even chance of deciphering it, my wife. She types it out and passes it back with comments, often unrepeatable. I then go through the typescript, revising once more, and above all attempting to trim the excess fat.

Characters, relationships, situations, backgrounds – I find that in order for me to get these right, I need to know far more than is necessary for the reader, and it’s hard to keep this surplus out of an early draft. I should imagine that at this stage I cut between five and fifteen per cent of a book. Now comes the final typing, the script goes off to my agent, and the three-pronged anxiety syndrome familiar to all authors begins to prick at the gut. First the agent has to get it, second he has to like it, third he has to sell it. The first a telephone call or an acknowledgment slip takes care of, but it’s a strong source of anxiety nonetheless, and I am always careful to ensure nothing leaves my possession unless I retain a back-up copy. The second is not automatic, not if you’ve got a decent agent. On the other hand, he won’t be too brutally dismissive, not if he’s got any soul and any sense! He’ll tell you you’re a genius, then he’ll say he doesn’t like it. But if he’s enthusiastic, then you know the battle’s half won. There may still be another round of revision if an editor feels strongly, and persuasively, that something needs changing. But these are the pains of the long-distance runner who sees the tape in view and knows that no blister on earth is going to stop him getting there.

Curiously, revision is a process I’ve come to enjoy more as time has gone on. Ideally, I think now I should like to hold on to my scripts for a couple of decades and keep on tinkering from time to time till I get them right. But when I started, the thought of altering those immortal words was like Moses taking a hammer to the tablets he’d just ferried down the mountain. I remember my first publisher-requested revisions consisted on my part of removing several ands and substituting commas. Things have changed and I am now able to wield the surgeon’s knife with a steady hand, not because I have less respect for what I have written, but because I have got more.

The other advancement of learning which took place was also, I suspect, common to most authors – the assimilation process by which the raw material of personal experience is tested against the needs of the story and not admitted until its colour, texture and taste match that of the imaginative creation. What must go is the self-indulgence of private jokes and personal references.

Particular research into backgrounds is one thing; the use of what you already know is much more difficult. I went to Italy to get background for Another Death in Venice and again later for Traitors’ Blood and a possible sequel. This process is one of observing, selecting, discarding, and is, in fact, much easier than writing a book set in milieus familiar from long usage. In A Clubbable Woman I used a rugby club based upon my own experience of the atmosphere and ethos of such a club. In An Advancement of Learning I used a north-of-England college not unlike the one I was then teaching in. In Fell of Dark I used the city I had been brought up in and the area of English countryside surrounding it. The dangers of close familiarity are not legal, though plenty of people claimed to recognize enough characters and situations to fuel a chamberful of lawsuits. (Interestingly, such identifications were nearly always wrong and, happily, few people are objective enough to spot themselves.) No, the real danger is artistic, that the familiar reality should become more important than the imagined story. We all know the type of tedious raconteur who grinds through acres of nonessential detail and would pause in his eyewitness account of the Crucifixion to inquire of himself, ‘It was on a Friday … was it a Friday? … no, it could’ve been Thursday … no, I’m wrong again, Thursday we had that nasty shower … it was definitely Friday!’ To the writer, selectivity is all, and to the tyro, this is perhaps the most difficult process. Art should not simply hold a mirror up to life, particularly to the author’s own life. That way you get stuck with one over-familiar face and a lot of uncontrolled background detail, and in any case, it’s all back to front …

I think that now after a couple of dozen books I am beginning to learn my trade … The ultimate stage of reputation, of course, which comparatively few reach, would be to have a name so powerful in market terms that it would sell anything. Well, the money would be nice, but I don’t know if I’m ready yet for the irresponsibility.

![]()

![]()

Keeping Track

Paula Gosling

Killing people for fun and profit has its upside. For me, it’s the research. I love that research. I pick a subject I find and go to the children’s section of the library and find all they’ve got on it. Then I use the bibliography to progress to adult reading, then expert reading, and so on, until I have it all in the palm of my notebook. Sometimes I even go and talk to experts face to face, and that’s the most fascinating of all. If I could remember all the things I’ve had to learn about in order to write crime novels, I’d be as smart as Dickens.

Unfortunately, each successive book I write seems to obliterate the last. I knew something once about hunting, about solar astronomy, about Spain, about telepathy, about jazz, about survival in sub-zero environments – all that good stuff. I also knew characters named Malchek, Skinner, Cosatelli, Stryker, Abbott … oh, lots of folks. And I remember everything, absolutely everything about all of them – until somebody asks me.

Interviewers can be tough, but the fans are the toughest. Damn, they are smart cookies. They notice everything and forget nothing. There I am, full of excitement and information about my latest book, and they ask me something like ‘Why did Professor Pinchman stay in his office that night?’ Or ‘Why did Malchek choose a Ruger rifle instead of a Remington?’

Who? What? Monkey Puzzle? Fair Game? Who wrote those? Me? Oh dear. Actually I think it’s a matter of criminal capacity. I mean, books are big, lumpy things, full of words and images, and I have just this small, round, size-seven head. In Fahrenheit 451 Bradbury had his characters of the future commit just one book to memory. One book each, right? So how can we be expected to remember eight? Oh, I see. It’s our job to remember. We’re writers. We get away with murder. True.

But we usually have to deal with just one murder at a time. All right, maybe two or three. Four? Well, certainly no more than ten. And we have to remember all the details of who was where and why they were there and what time it was and why the others weren’t there and what the weather was like the previous Tuesday. And there are the noises and the smells and the colours, and how long the strychnine took to act, how much noise a .22 makes in a heavily-draped 20-foot by 18-foot room, how many men Drusilla slept with at college, why the floor creaked and why the mouse ran after the cat. Plus there’s the rest of my life to think about: I have responsibilities, you know. It’s not easy being a woman with a career. I mean, what am I going to cook for dinner tonight and who’s going to sort out the laundry and … and … no, I’m not getting shrill, I’m not, I’m not!

![]()

![]()

Reading for Pleasure

Jonathan Gash

Writing fiction can actually dictate what one reads, a truth I discovered quite a long time after I first hit – well tapped – the literary scene. More, writing fiction may modify the pleasure one derives from reading.

To see how my illustrious predecessors went about it, I consulted all the Reading for Pleasure articles, and was at once struck by the poshness of their choices. I really mean it. Between The Gulag Archipelago and Neugroschel’s translation of Great Works of Jewish Fantasy there’s not a lot as far as I am concerned, and in my days as a train-shocked commuter I needed a minimum of five tomes a week to stay sane. Another thing: there’s an absence of stories in what my colleagues write about, judging from their recommendations, but maybe I picked back numbers ‘with biasing unrandomness’. I wouldn’t know. But some books, such as those by P. M. Hubbard, do have the peculiar hallmark of readability – which is about it, as far as I can see.

Can the very labour of authorship, of itself and in some subtle way, decide the choices one makes? Leaving aside the business of ‘collecting drop material for a book’ and ‘culling for background’ (I only learnt these terms recently), I actually believe it can, and that very often such influences will make one fly in the very teeth of learned critical opinion. And here’s the proof: Frederick Forsyth’s The Devil’s Alternative. Quite unashamedly, I tell you I liked it. Fully aware of the risk of biasing unrandomness again, I was quick to get through it before that ghastly display appeared in Dillon’s window and brainwashed all pedestrians within bucket distance. The point is that nobody ought to approve of it, presumably for the same reasons that so many of us ought not to have approved of Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal. We learnt from Robert Robinson’s book programme shortly after the book was published that Forsyth suffers from a congenital form of the Inadequate Characterization Syndrome. In fact, when the poor author was called in to explain he got quite a drubbing from the sixth-form-of-the-air for it. The story was seen as a routine game of noughts and crosses, with the odd nought disguised as a supertanker, and the odd cross exploding now and then, but all really nothing but a game of OXO. Wrong, from one who found himself reading it for no other reason than as a kind of self-imposed duty, and who gained pleasure thereby: interested, speculation pleasure this time.

Fiction, I feel, should be about recognizable ‘selves’, whether they be people larger than life (Wilbur Smith’s Hungry as the Sea is an engrossing example) or even animals – and here I strongly favour the gripping Night of the White Bear by Alexander Knox instead of the much more vaunted and trendy The Plague Dogs, or all those wee rabbits on Porton (sorry, Watership) Down.

On a daughter’s instruction I tackled the science fiction bestseller Alien, which ended up as a disappointingly mild curiosity as to whether the beautiful space heroine would make it to Earth, or whether her kitten, too, would turn out to be a Thing in her space shuttle like all the rest. I didn’t mind, though. The spinoff of being able to exchange views with an offspring is not to be sneezed at these days, and I’m on the lookout for more of what young people read. The best of them is Frank Herbert’s interesting SF Dune, but E. M. Corder’s The Deer Hunter, another popular seller (‘Now a Searing New Film’), proved a let-down. I could not explain my sense of having read nothing once I’d finished the book. The answer was in the cover – the book is, in fact, that new phenomenon of the non-novel novel – that is, a jolly good sequence of events but based on a screenplay, itself based on the story by Cimino, Washburn, Garfinkle, and Uncle Tom Cobley et al. I was reminded of Danny Kaye’s famous joke song about a film ultimately based on someone’s inspirationally profound punctuation mark.

Other production points can be as mystifying. All sympathy for Peter van Greenaway’s crime novel Judas! which was spoilt for me by serious misjudgments in the printing and production. This excellent story is based on the idea of the discovery of a gospel written by Judas, no less, which discloses that Christ was a nerk and a charlatan, St Peter a blackguard, St John a fraud, and so on, while the only saving grace, as it were, is Judas himself. I blame the publishers, who, for very little more expense, could have italicised the ‘gospel’ flashbacks, and got rid of those insanely narrow margins for top and laterals. Unwise economies that seriously detracted from my enjoyment of the book, a bright idea for a good story based straight on the Nag Hammadi scrolls. Incidentally, the real Testament of Judas Thomas found in 1945 laconically infers that Jesus possibly had a twin called Judas …

A testy reader once wrote to me that I’d ‘never got a police rank right yet’, little knowing the neuroses she was generating. (Do I grovel? Do I keep it up, thereby enticing her to read me with even greater ferocity?) No such anxieties in N. J. Crisp’s The London Deal, where his character Kenyon’s difficulties are with his police superiors and inferiors alike, with every rank scrupulously stated and the story as interesting as it was cracked up to be. The only thing wrong is the dust jacket, which is of the sort over which the Observer critic recently perorated, calling them dull and unimaginative. One gets drawn in again, really wanting to know how Inspector Kenyon scores over that toad of a man in New Scotland Yard, as surely he must.

Doctors, however, must sometimes read for relaxation, which may actually be nothing to do with rest or pleasure. Doctors, therefore, must read Dick Francis. Little risk, I find, of being deeply drawn in here, but his evenly written novels may be started, resumed, or finished at any hour of day or night whether one is knackered or not, and put down in an untroubled frame of mind. I suggest Risk, High Stakes, and In the Frame for starters; the most likable crime books on the market.

Pleasurable reading from neat and concise analysis? A clear and somewhat unnerving possibility, after reading Julian Symons’s Bloody Murder. Not a novel, but an erudite and readable account of the evolution of the crime novel which goes some way towards explaining why it is that one novel proves to be a turning-point in a genre and others not. (Incidentally, why genre? Will kind, clone, type, style, category, variant, or some other such not do? It sounds too affected for words.) A remarkable book, but it carries an important question for me: Mr Symons has an enjoyable knack of being able to follow that evolutionary thread when it lies buried among hundreds of thousands of titles, but where is the chap who will explore medical publications in a similar way? Analytic overscans (another new phrase I’ve been dying to use) seem to be the peculiar attribute of the non-medic.

But you can have too much analysis. In an effort to posh up the list of books I could cheerfully admit to having read and delighted in, I found a text wherein selections from modern poets were accompanied by various poets’ comments on their works. The volume fell open at a spine-chilling paragraph written by a northern poet who received national acclaim for his Terry Street. It ended with a description of a gruesome futuristic vision of scurrying hordes of analysts of every sort, each with diplomas, heading intently for every known author, ‘silent, and very fast’. It makes me think that reading for pleasure is merely the act of running like hell in the opposite direction. And writing too, at that.

![]()

![]()

Don’t Give Up the Day Job

Janet Neel

I wrote my first detective novel when I was 27 and in a bad way, recovering from the failure of my first marriage and the realization that I had trained at huge trouble and expense for the sort of legal career that wasn’t going to suit me. All my own fault: I had intended to be an international lawyer, swanking around pinning writs to oil ships like my mentors at Cambridge, but had changed tack to qualify as a solicitor so that I could earn good money while my then husband went to the Harvard Business School. As the marriage collapsed and I came home unable to go on with my job in the USA designing war games for their Defence Department, I found I could not decide what job to do or indeed to work at all. Rather than stay in the family home with my dismayed mother, I settled down in a flat with two nice women I had never met before and wrote a full-length detective novel in three months. I had always read crime novels for preference, majoring on the works of Marjorie Allingham and Josephine Tey.

I sent it to the late Celia Ramsay, a family connection who liked it but warned that substantial work lay between me and publication. Surprisingly this cleared my head. I understood that the solitary life of a writer was not what I needed at that moment; I wanted a good high-prestige job with lots of new people in it where I could be successful, as once I had been at Cambridge, England, and in Cambridge, USA. So I thanked Celia and filed the book and went to work on John Laing Construction sites, interviewing their labour force on behalf of a publicly funded consultancy to find out what they wanted out of life – stability or the best money and why. From there, much cheered by having been everyone’s favourite thing on the sites, I got into the Civil Service as an experiment in which a dozen of us were taken into the administrative class at a senior grade.

I did thirteen years in the service, and was a success and found a good husband and had three children; then did four more years in a small merchant bank, headhunted to help them get government work in privatization before I went back to writing. Waiting for a substantial deal to come off – it was going to make my name – I found that writing stopped me fretting. Writing Death’s Bright Angel – about the work of the Department of Industry in rescuing failing companies – I realized that my true métier was as a commercial lawyer; it won the John Creasey prize. Miles Huddleston of Constable helped me get there by giving me Prudence Fay – who has since edited all my crime novels – as well as one vital piece of advice. ‘Do not,’ he said over a good lunch, ‘even think about giving up the day job.’ He meant don’t think about it until about book four, but I realized that I could not be a full-time writer – I needed people, activity, the chance to use my commercial skills, and the ability to make more money more easily than most writers ever do.

I also understood that like most writers I was better off writing what I knew and my usable experience was expanding very fast. The second book, Death on Site, is about murder on a construction site. I wrote it on holiday in Scotland, but what was before my eyes was the big Western Avenue site on an overnight shift – a ghoster – with the hard-drinking Laing’s travelling men all around me as I watched them move huge concrete beams across the closed main road. The third book – shortlisted for the Gold Dagger – is about my old college Newnham and is based on my experience as an associate fellow and trustee of the Appeal Fund. And so on it goes; setting up a restaurant with my youngest brother provided the wherewithal for A Timely Death. My most recent book, Ticket To Ride, comes from my experience helping George Robertson, then Secretary of State for Defence, and thereafter Secretary General of NATO during the Kosovo war. There is another book to be written about the war in Iraq and another yet about my 12 years on the Board of the London Stock Exchange, but I could not have written any of these novels without my various day jobs.

![]()

![]()

Writing to Relax

Bertie Denham

A handful of politicians have written thrillers and several authors of crime fiction have been elevated to the House of Lords. I suppose I am unusual in that I had a long career as a whip in the upper house, and spent twenty years as Deputy Chief Whip and then Chief Whip. The work of a whip is as fascinating as that of a crime writer, and it requires just as much understanding of human nature. What is perhaps less obvious is that it’s a highly pressured job, since in politics you never know what is going to happen next. A whip needs to be available seven days a week and can be called upon at very short notice to deliver (or at least, try to deliver) the necessary votes.

For me, therefore, writing crime fiction became a form of relaxation. It has helped me to escape from the demands and stresses of my unorthodox ‘day job’. There are literary connections in my family – one of my Christian names is Mitford, reflecting the fact that my mother was a first cousin of Nancy Mitford. I’d always enjoyed reading thrillers, but it was many years before I felt inspired to write a book of my own. Really, the urge to become a thriller writer came out of the blue, during the later stages of my career as a whip.

From the 1960s onwards, Dick Francis, Gavin Lyall, and John Le Carré were favourite authors, long before I met them in person and was elected to join them in membership of the Detection Club. The help and support that established writers give to aspiring novelists is, and has always been, immensely valuable. When I was working on my first book, I was lucky to benefit from the encouragement of the Labour peer Lord Ted Willis, who is now perhaps best remembered as the creator of Dixon of Dock Green.

That first book was The Man Who Lost His Shadow, which introduced my ‘series detective’, Derek (Viscount) Thryde, a young Conservative whip. The story was set against a background of parliamentary life, country houses, and country sports, so I was following the traditional advice of ‘write about what you know’. As my writing developed, though, I tried so far as possible to vary my approach; for instance, my settings ranged from Scotland to the Caribbean. As a result, I found myself needing to research a wide range of settings and activities with which I was much less familiar.

The fascination of this research (for instance, exploring the River Orwell and the Suffolk coast while planning a chase scene) added to the pleasure I took from more generally from my writing career. It represented such a contrast – a complete break from my principal working life – and because of that, I found the company of fellow crime novelists delightful, just as I found that writing crime fiction was unexpectedly therapeutic.

![]()

![]()

Social Media and the Death of Nancy

Elly Griffiths

You’ve written a brilliant book, now it will sell itself. You can retire to your desk, sharpen your quill and start on the next one. Well, even in the days of quills it wasn’t that easy. Charles Dickens promoted his books tirelessly. He toured America, on one occasion earning over ninety-five thousand dollars for seventy-five readings, and was so famous that people recognized him in the street (an almost unheard-of experience for a writer, even in this age of social media). In fact, it was a reading that killed Dickens. He suffered a stroke after an over-enthusiastic rendition of the death of Nancy in Oliver Twist and died shortly afterwards, aged just fifty-eight.

Do we have to promote our books until it kills us? Is writing a great book – as Dickens undoubtedly did many times – enough? Or is there a middle way between acting out gruesome death scenes to an enthralled audience and keeping your book a delicious secret?

Dickens was lucky (a near-fatal railway accident and Bill Sykes aside). He was naturally gregarious and an enthusiastic actor. But writers are not necessarily like this. After all, we have chosen a profession that involves spending a lot of time on our own. There is no guarantee that we can keep an audience entertained with witty and erudite anecdotes, though a surprising number of authors can. And, even if we do venture out, does this really help to sell our books? We have all slogged miles to a library or bookshop, only to find an audience of four people, two of whom are employed by the establishment and one of whom is lost. I once did an event with three other crime writers to find a room full of empty chairs and an audience of one, a woman who then proceeded to tell us about her own (mysteriously still unpublished) dystopian novel. Scottish author James Oswald recalls reading to an audience of three, one of whom rushed out halfway through, muttering something about not being able to take it any more. James never worked out what caused such a violent reaction, though when he met one of the other audience members a few years later, he said that he’d never forgotten the event. Simon Brett tells the story of an author on an Arts Council tour who arrived at the venue and found there was only one man waiting. The author suggested to his lone auditor that, as there were only two of them, they might just repair to the pub. ‘No,’ the man insisted, ‘you must do your talk.’ It turned out that he’d been employed to play the piano in the interval.

Performing to an audience of one grumpy pianist doesn’t sell books but it might well bear fruit in other areas. Travelling to an event shows goodwill and it’s great to support libraries and bookshops. My first editor once described it to me as ‘lighting small fires’. Maybe our dystopian novelist went home to Mr Dystopia and enthused about our books, maybe he recommended them to his book group, maybe someone tweeted about them – it all helps. But lighting small fires can be expensive. Few libraries can afford to pay speakers and you can quickly find yourself out of pocket after paying for fares and a consoling Twix or two on the journey home. It’s sensible to group a few such events together but then, before long, you are ‘on tour’, a gruelling slog around Travelodges and Premier Inns that saps the soul and, crucially, cuts into your writing time. Of course, book events can be fantastic. Libraries and bookshops are beautiful places; book people are always nice people; and it’s wonderful to meet those most wondrous of beings, your readers. But the hard fact is that you need a roomful of such deities, all willing to buy a book, before your trip makes commercial sense.

Is there anything you can do to promote your book without leaving home? Of course there is. Even writers have heard of the internet, right? So you do the basics: you create a website, set up a Twitter account and a Facebook page, maybe even go crazy and add Instagram. Now what? Do you add a photo of yourself, looking mistily glamorous and writerly? Do you add a picture of your dog/cat/guinea pig? Do you immediately start talking about your book #buyitnow #specialoffer? Do you ignore vulgar consumerism and start talking about favourite films or enter into a spirited Doctor Who vs Blake’s 7 debate? The answer is, probably a mixture of all these things. It’s nice to see what authors look like but, frankly, it’s even nicer to see their pets. If you don’t have a pet, borrow one or persuade your neighbour’s chihuahua to stand winsomely beside your laptop. You need to tell people about your new book – that’s why people are following you in the first place – but please don’t make this your only interaction. It’s very tedious to be harangued all the time. Instead, talk about your friends’ books. This has several advantages. One, it will make you look like the nice person you are. Two, your friends will be pleased and, if you’re lucky, they will return the compliment and talk about your new publications. Three, it makes you look good to have wide-ranging and eclectic tastes and, who knows, you might even enjoy the books for their own sake.

Equally, don’t be afraid to talk about something other than books. Twitter, in particular, is a good place for entertaining but meaningless debates (and, of course Blake’s 7 is better, it goes without saying). Readers will like to see that you have a hinterland and you can spend many a happy hour ranking Bruce Springsteen’s studio albums in the company of other obsessives. But there’s the rub. Social media is the thief of time. You can disappear down a rabbit hole and not return for the best part of a day. Also, it is easy to get into petty arguments and nothing says ‘don’t buy my book’ like a thread full of veiled insults. It seems a sensible strategy to limit your social media time to an hour in the morning or evening. On Instagram it’s meant to be an advantage to post at the same time every day, preferably in the early afternoon when America starts to wake up. So post a nice picture of your chihuahua friend and don’t look at the comments until later. However, once you do look, make sure you answer or at least ‘like’ everything. Interaction is the key. Build up a relationship and soon you will have that most valuable of things: an online following.

But does having an online following sell books? I conducted a brief, unscientific poll amongst my crime writer pals and the consensus was that the single most valuable thing you can do is create a mailing list. Once you have collected the names of people who actually want to hear about your books, you can then send them newsletters, special offers and details of events. People are also talking about ‘street teams’, key readers around the country who will evangelize about your books. You can set up special Facebook chat groups for these fans or, better still, meet them in person. But this all takes time and a certain amount of technical know-how. I have never mastered Mailchimp with its annoying monkey. While I do send out a monthly newsletter, I have to admit that it is administered by my publisher. This is not ideal, say those who know, because your mailing list should belong only to you. Of course, self-published writers have always been better at this sort of thing. To be a successful independent author you don’t only have to understand the Amazon algorithms, you have to know how to connect with your readers. The indies are way ahead of traditional publishers in this area. It’s a strange thing; no one has ever walked into a shop and asked for ‘a HarperCollins book’ but authors have been slow to understand that they, not the publishers, are the brand.

What can you do if your time and inclination are severely limited? If you only do one thing on social media I think it should be this: tell people when your book is published and say something interesting about it. Don’t just post a link to Amazon or a bookshop, say something about the research or the history behind your latest literary offering, say you enjoyed writing it, post a picture of your neighbour’s chihuahua sniffing the pages. Ian Rankin on Twitter is a good example of a high-profile writer who makes you feel as if you are interacting with the real person. He doesn’t just tell sell his books, he posts pictures of himself in Edinburgh’s Oxford Bar, he shares music links, he recommends other writers, he always responds to comments. This is why people follow writers on Twitter.

But be careful. At its best, social media is a community but at its worst it can be a dark place. Remember, your aim is to be visible but the downside is that you’re now visible. It’s not just your loyal readers who can contact you. It makes sense to protect yourself a little. This is where your trusty animal friend helps again. You can post pictures of your pet cat in lieu of photographs of yourself and your children. This will foster a sense of intimacy without giving too much away. Ditto chat about music and books. Try to steer away from politics, though I know it’s hard sometimes. Don’t respond to anything offensive, just block them and move on. Think before you post and never, ever go on Twitter when drunk.

So what should you post and where? The received wisdom is that Facebook is a network of people while Twitter is a network of ideas. It’s not an accident that Facebook has ‘friends’ and Twitter has ‘followers’. Facebook and Instagram posts last longer. Twitter is ephemeral – which is sometimes a good thing because it also doesn’t have an ‘edit’ button. So, if you spell book ‘boko’, as I often do, simply post again with a rueful smiley face. Instagram is a visual medium so this is the place for your most artistic photographs. Purists like their Instagram ‘feed’ to look curated, so some users stick to limited palettes and themed pictures, such as artful shots of books and coffee cups. For me, this is slightly boring. I appreciate a nice picture as much as anyone (I follow several landscape and cute animal accounts) but I like my authors to be more interesting and multifaceted. The demographics show that younger people prefer Instagram and also that they are quite prepared to spend money on the basis of an attractive post, so add buying links. Facebook is still the best place to chat with your readers but you should respond to all messages on Twitter and Instagram too, even if it is just to like them.

Just for you, this is my brief guide to publication day on social media:

1. Post a video on Facebook with buying links. Author-opening-box-of-books is cheesy but effective. Make sure you have an animal in the video.

2. Post several times on Twitter with different messages each time. Add a key line from the book or, better still, an audio link. Thank people who have helped you. Add an amusing animal gif.

3. Post a beautiful picture of the book on Instagram. Include a buying link and hashtags but don’t go overboard. Sign up as a business account so that you can see your statistics (though they are often very depressing).

And, if you really can’t stomach doing any of this, don’t worry too much.

The only thing that you, and only you, can do is write the books. So just keep on doing that – though if you want anyone to read them, investing in a chihuahua might be a good move.

![]()

![]()

The Joy of Writing

John Le Carré

I love writing on the hoof, in notebooks on walks, in trains and cafés, then scurrying home to pick over my booty. When I am in Hampstead there is a bench I favour on the Heath, tucked under a spreading tree and set apart from its companions, and that’s where I like to scribble. I have only ever written by hand. Arrogantly perhaps, I prefer to remain with the centuries-old tradition of unmechanized writing. The lapsed graphic artist in me actually enjoys drawing the words.

I love best the privacy of writing, which is why I don’t do literary festivals and, as much as I can, stay away from interviews, even if the record doesn’t look that way. There are times, usually at night, when I wish I’d never given an interview at all. First, you invent yourself, then you get to believe your invention. That is not a process that is compatible with self-knowledge.

On research trips I am partially protected by having a different name in real life. I can sign into hotels without anxiously wondering whether my name will be recognized: then when it isn’t, anxiously wondering why not. When I’m obliged to come clean with the people whose experience I want to tap, results vary. One person refuses to trust me another inch, the next promotes me to Chief of the Secret Service and, over my protestations that I was only ever the lowest form of secret life, replies that I would say that, wouldn’t I? After which, he proceeds to ply me with confidences I don’t want, can’t use and won’t remember, on the mistaken assumption that I will pass them on to We Know Who. I have given a couple of examples of this serio-comic dilemma.

But the majority of the luckless souls I’ve bombarded in this way over the last fifty years – from middle-ranking executives in the pharmaceutical industry to bankers, mercenaries and various shades of spy – have shown me forbearance and generosity. The most generous were the war reporters and foreign correspondents who took the parasitic novelist under their wing, credited him with courage he didn’t possess and allowed him to tag along.

![]()

![]()

Different Books; Different Problems; Different Solutions

Len Deighton

We all have our own way of writing our books and each book is likely to bring new demands. What works for me might not work for you but you might find some of my experience useful. Bear in mind that I have been described as a very slow worker who is addicted to research.

My research has taken me to many foreign countries. I like to be with my wife and sons and so we usually have had to rent somewhere to stay. Shopping and conversations with neighbours enrich one’s understanding in a way that a single man in a hotel could never hope to find. My wife is fluent in many languages and nowadays my sons – who acquired their language skills at schools in France, Germany and Austria – manage Japanese and Mandarin too. My linguistic family has greatly helped for my research. And their presence has created friendships with many interesting people in many countries.

But before research there must be preparation. Is your proposed story interesting: with a firm structure and satisfying end? Is the substance of your story enough to sustain a book? Is the story best told in the first person? Once writing starts I need the momentum that comes from writing and revising every day.

The preparatory stage brings decisions about where the story takes place, and at what season of the year. Are there technical aspects of the story and if so can you handle them? I have abandoned three books halfway through and it is a miserable experience. One was an espionage story centred upon an orchestra travelling behind the Iron Curtain. I could read a score, and tap a few bars on a piano, but it didn’t take long for me to admit that I didn’t know enough about music. Another abandoned book came after I had spent months with the US Air Force. They sent me to a fighter base in East Anglia. They equipped me with a flight suit and all the paraphernalia; they gave me an air-crew physical exam and countless jabs. They gave me a seat in the ready room and let me fly backseat in their Phantom fighter planes and live with the pilots, among whom I formed friendships that still flourish. Suddenly North Vietnam sought peace; The US President sought re-election and the fighting ended just as I was about to join a tactical fighter squadron in the war zone. Everything changed and I put all the work aside.

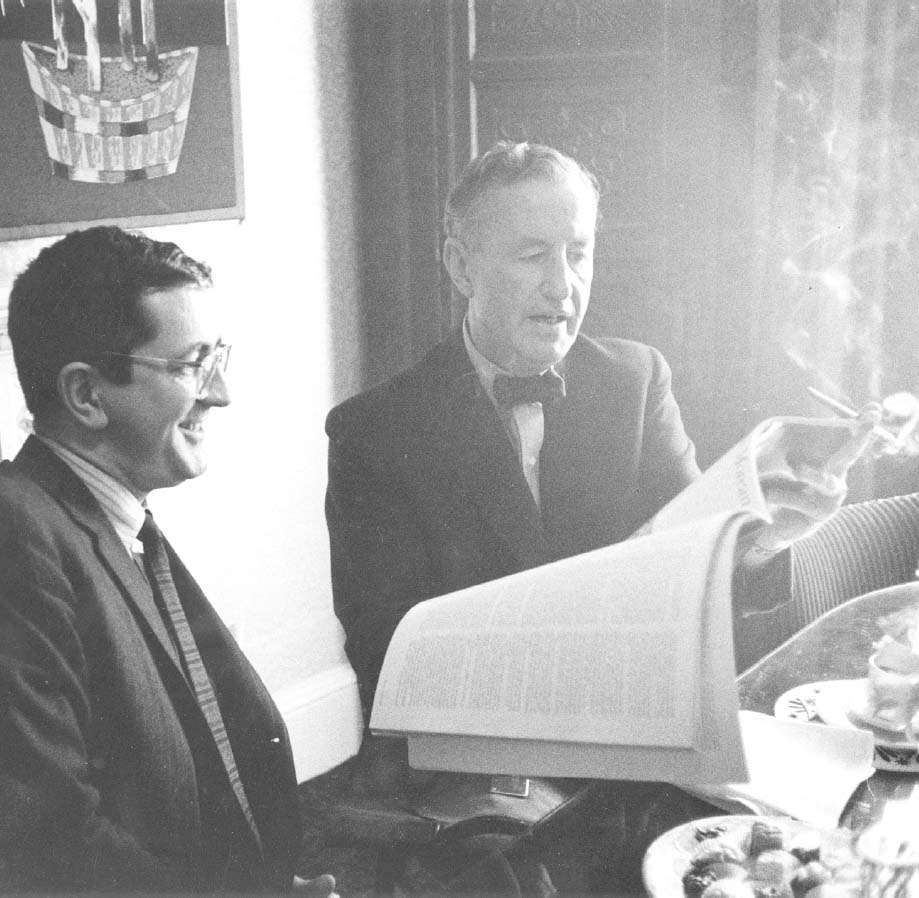

Lunch with Ian Fleming. At his suggestion we went to a private room in his favourite restaurant, ‘The White Tower’ in Percy Street. He had been a regular customer since his wartime days at the Admiralty.

The date was March 1963. The previous November Ian had chosen The IPCRESS File as one of the books of the year for the Sunday Times Christmas Selection. We both had roast duck – a speciality of the house.

The photo was taken by Jack Nisberg, an American freelancer who was a close friend from my own days as a photographer.

The third abandoned book was to be about world-wide revolutionary movements. I did a considerable amount of research on Russian Bolsheviks and I mixed with troublemakers, Trotskyites and terrorists. I talked to various police specialists and a retired MI5 officer. But with a detailed outline and two or three false starts I gave up.

The time span of your story will have an effect on the pace of the narrative and the interaction of your characters. Bomber, about one RAF bombing raid, its German target, and the radar and night-fighter interception, covers exactly 24 hours, providing a concentration of time but a dispersion of place. For writing Bomber I had the advantage that my service in the RAF included flying in Avro Lancaster bombers and De Havilland Mosquito fighters. The RAF Museum staff allowed me to climb around inside their precious Junkers Ju 88 and the Imperial War Museum let me sift and scan hours and hours of Junkers instruction film.

In contrast, Winter describes a Berlin family from 1900 until 1945. The family is torn to pieces by Europe’s recent history. Both books required a carefully researched and cool look at the past, but from an author’s point of view they were completely different. Eyewitness accounts (including diaries and memoirs) have always been my first choice for research. Many history books restate and endorse the myths and errors of previous accounts, repeating wartime propaganda. It was exasperation that impelled me to write three military history books, Fighter, Blitzkrieg, and Blood, Tears and Folly, to blow away some of the nonsense.

History books, and fiction reliably based on history, bring a need for efficient reference systems. For Bomber I used coloured papers for my typescript to distinguish between chapters about the RAF, German air force, German radar and the German civilians. By looking at the coloured edges I could see if the story was sufficiently balanced. Bomber required a great deal of research and for easy reference my workroom walls were covered in maps and diagrams. Revisions, corrections and edits are always a part of my writing process; and scribbling between the lines on typewritten pages, as well as cutting them up and rearranging paragraphs, kept me on my knees brandishing the glue pot. The engineer who came to service my IBM electric typewriter once said, ‘Your poor secretary; she says she has retyped one of your chapters twenty-five times!’

‘Yes,’ I said trying to look penitent. ‘But what can I do?’

‘Let me take you to Shell head office’ – the Thames-side office block also on his beat – ‘and see how they produce their instruction manuals.’

The answer was a computer. It was 1969 and the name ‘word processor’ had not been coined. Within a week one of these massive IBM machines was swinging on a tall crane to get it through the second-floor window of my little house in Merrick Square, London SE1. Many years later an American researcher wrote a history of word processing and acknowledged that I was the first person – by many years – to write a book using such a contraption. It was Bomber, and in my acknowledgements I thanked the people at IBM for their wonderful machine. This established the date of my claim. At this point I must give credit to my old friend Edward Millard Oliver who spotted some pre-publication material on the internet and contacted the American writer. And I must also admit that it was my brilliant Australian secretary Ellenor who mastered the machine’s fits and starts and temperamental tantrums.

If preparation is the most vital part of writing a book, it is still more a saving of time and money for anyone producing a film, which is what I did in the Sixties after buying the screen rights of Oh! What A Lovely War from Joan Littlewood. (The show was composed of words sung, spoken or written by the participants, and so were my additional sequences.) Moviemaking is a multifarious business. The producer buys the screen rights of a book or play, writes a screenplay (or has it written), finds someone to put up the necessary millions of dollars (in my case Paramount Pictures) decides about the cast (whether they are available and affordable in the film budget), engages a director and other vital employees such as casting director, costume designers, location manager and lighting cameraman. It is useful to have an executive producer and I was lucky enough to have a brilliant and experienced one, a wartime Spitfire pilot named ‘Mack’ McDavidson. He was in effect my partner and the film owes a great deal to his skills and faultless administration.

It was winter. My screenplay brought the centre of action to the Brighton Pier. It was obvious that I could not start shooting until the seasonal weather changed. With expensive offices in Piccadilly and a bank balance severely depleted by my personal purchase of the Oh! What A Lovely War screen rights, I urgently needed a deal and some money to pay my rent and the bills.

My agent, William Morris, took my script to Charlie Bluhdorn, the Anglophile boss at Paramount. It was Charlie’s enthusiasm and faith in me that brought the project into life. But to bridge the winter gap, William Morris obtained additional finance for Only When I Larf, a book about confidence tricksters that I had recently completed. Larf was mostly an indoor shoot. My art director, John Blezard, built an amazing penthouse suite in a dilapidated warehouse near Tower Bridge (so attractive that it featured in February 1968 House & Garden). Locations in New York City and sunny Beirut provided outdoor scenes.

For Oh! What A Lovely War I borrowed a locomotive, rented and renovated both Brighton piers and hired the band of the Irish Guards. There is no need to tell you how vital preparation was in such a double production schedule. I worked night and day and checked out everything, from the sets and costumes to cloaking Brighton’s municipal rubbish dump with fake snow (for the Christmas truce sequence) and arranging with a friend for the flight of a vintage World War One aeroplane. I was concerned about the movements of all the cast, because clumsy movements marr a film. Eleanor Fazan the choreographer made a vital contribution to the action and I learnt a great deal while watching her at work.

Having spent seven years as an art student, I was keen to make Oh! What A Lovely War visually satisfying. It was a chance to bring into my films people whose work I knew was exceptional. May Routh, an art school friend, worked on the costumes and later made a name in Hollywood; another art student colleague Ray Hawkey designed the stunning titles. I engaged Pat Tilley, an accomplished artist friend to keep the untried director (Richard Attenborough) supplied with storyboards that sketched camera positions for each day’s shooting.

When I was a student at St Martins School of Art in Charing Cross Road, I shared a postbox address with several others, including some congenial confidence tricksters. They were amusing people and amazingly self-righteous as they explained that they only outwitted greedy victims. Several years later I recalled their stories and wrote Only When I Larf. For me every book offers a chance to experiment. In this book I gave each of the three main characters – a young man, a middle-aged man and a woman who changes her affection – a first-person chapter. Each character tells their story, which often contradicts and overlaps the other two. It was fun to write and revealed to me how useful it can be to have your characters ‘remember with advantages’, as Henry V puts it on St Crispin’s Day. Or sometimes tell whopping lies.

Like most writers I begrudge wasted experience (even my abandoned revolution research was used in a South American locale for MAMista). Close-Up revisited my many and varied experiences in the movie business. I was on friendly terms with the top men at Paramount and saw the tough commercial decisions being made. I signed renowned actors and actresses: Laurence Olivier, Maggie Smith, John Gieldgud, Ralph Richardson and all the Redgraves. And I bargained at length with their unsentimental agents. My journey through the jungle left me with abundant material for a book. Close-Up is a story about the vendettas, coercion and backstabbing social politics that I had seen at first hand. I wrote of the bitterness and stress that haunts the acting profession. To focus the drama, I depicted a film star battling against the impending downturn of his box-office value. I wanted the intimacy of a first-person plus an overview. So I entwined the story of the actor with a commentary by his biographer.

Some stories nag at one’s brain. Several readers who had read Bomber wrote to suggest a book about the US 8th Air Force. One Malcolm Bates sent me many long letters, photos and books; his enthusiasm was inspiring. The American airfields were like small towns: not only hangars and well-equipped workshops but pharmacies, libraries and prisons; chapels and ice-cream parlours; dental surgeries, hospitals, movie theatres and tailors’ shops.

Anecdotal episodes were added when an ex-RAF officer, Wing Commander ‘Beau’ Carr, infiltrated me into a group of American veterans of the 91st Bomber Group on a visit to England the bases where they had been stationed.

‘That’s where I lived’, one of them told his wife. It became the first page of Goodbye Mickey Mouse.

Initially I proposed to write each chapter in the first-person viewpoint of each of the major characters. My American editor, Georgie Remer, expressed alarm. She knew of no writer who could successfully manage the many varied American regional accents and speech patterns that I would need to master. I drastically modified my plans. I would still focus each chapter on a character but I would write it in the third person and look over their shoulder.

Goodbye Mickey Mouse was the result of numerous suggestions but the birth of SS-GB is easier to explain. I was drinking coffee in the office of Tony Colwell, my editor at Jonathan Cape, together with Ray Hawkey the designer. It was quite late and we had just finished choosing photos and captions for Fighter, a history of the Battle of Britain.

‘No one knows what would have happened had we lost’, said Tony.

‘The Germans had plans ready’, I said. ‘I have a shelf filled with books and official papers that reveal their ideas.’

‘Would it make a book?’ said Ray.

‘It never happened,’ I reminded him.

‘It’s called an “alternative world” story’, said Ray.

I had never heard of this category and it didn’t appeal to me at first. But I went to my library and the more I read, the more interesting it became. In the event I didn’t use much of the German material. It was a fascinating subject and I wrote it in the format of a detective story; murder on page one and solution on the last page. The central character was a Scotland Yard detective, ‘Archer of the Yard’, and I used locations that I remembered from my wartime days in London.

I like to write in the first person despite the limitations it brings (such as having the same person present in every chapter). So I told the story through the eyes of Archer. But as I was typing the final chapters I hit a brick wall. No matter what twists and turns I considered, there was no way out. So I dumped the whole typescript: converting it to third-person narrative would end-up lumpy and crude. Instead I took a new ream of paper and started all over again. It was a sobering example of poor planning, but the rewrite taught me a lot about story construction and about characterization too.

So where are all those spies? We authors know that readers will not tolerate the use of coincidence to facilitate our plots. But in real life, coincidence pops up time and time again: and that’s how my life has been in regard to the espionage community. During the 1960s our next-door neighbours in Merrick Square were Mr and Mrs Nicholas Elliot. He was a senior spook who had come back from Beirut, where he had been talking to Kim Philby, the KGB spy. Philby was offered a pardon in exchange for a complete and detailed confession. Elliot was tipped to become head of MI6 and Merrick Square was conveniently close to his office in Vauxhall Bridge Road (which was next door to my publisher). Elliot did not get the confession nor the top job. Many years afterwards we were living in a small village near Cannes while I worked on Yesterday’s Spy, which is set in that region. Elliot’s wife was again our neighbour.

There were other coincidental encounters with the espionage world. Visiting a friend held in HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs on a sunny day when visitors and inmates were gathered in the grassy interior lawn, I found George Blake, one of Russia’s most successful agents, seated at the next table. Maxwell Knight of MI5 and Sir Maurice Oldfield, the head of MI6, were friends of friends. They were everywhere. One didn’t have to look beyond our writing fraternity to find men who had worked in the service.

It all began in May 1940 when, in the middle of the night, my parents and I watched the police arresting Anna Wolkoff, our next-door neighbour in Gloucester Place Mews. Anna was the daughter of Admiral Wolkoff, who had been the Russian naval attaché until the Revolution. She was a friendly neighbour and her success as a fashionable milliner enabled her to give dinner parties to which influential people were invited. My mother cooked and served at those dinners. Anna was bitterly resentful about the communists who had taken over power in Russia. This was a time when communists abounded. Encouraged by gullible nincompoops such as George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, many otherwise sensible people betrayed their country to support Stalin’s empire, where a million Russians were being murdered each year and countless others sent to labour camps.

Others believed that Hitler’s totalitarian and militant Germany was a bulwark against Stalin’s expanding communist empire and should be tolerated if not helped. It was mostly people of this belief who were guests at Anna’s dinner parties. From the table talk Anna sifted useful information, assisted by Tyler Kent, the cipher clerk at the US Embassy, who lived nearby at 47 Gloucester Place. Anna’s notes of the chatter revealed the political sympathies and prejudice of Westminster, Whitehall and beyond. It was valuable material and it all went to Berlin by means of Tyler’s access to the American diplomatic bag.

The trial was held in camera and the names of Anna’s dinner guests were never made public. Anna was sentenced to ten years in prison; Kent to seven years. Later I was shown some records of the arrest. The story had been changed so that Anna was arrested in her parent’s home in South Kensington. There was even a handwritten notebook page from the arresting police officer. It was all an official fake. The authorities had decided to obliterate all mention of her real home and the dinner party guests. My mother was never questioned and neither were the other neighbours in the mews. Some said that Joseph Kennedy was one of Anna’s regular guests. His widely expressed political views suggest that he would have fitted in to the conversations well.

Whether any of this influenced my first book, The IPCRESS File, I am still not sure. I don’t know why I wrote it. Most successful authors seem to have had the writing bug since childhood. I didn’t have such a driving ambition; I scribbled and fumbled. I threw away more pages than I kept. It started as a pastime and even when it was completed I put it aside and forgot about it.

The critics were kind to me. But the mood of The IPCRESS File that distinguished it was its ordinariness. The main character was not a hero; he was like the people I grew up with, and I didn’t know any heroes of the sort found in books. It was this ordinariness that I wanted to explore more fully when many years later I began the Game, Set and Match trilogy that became the nine Bernard Samson books.

Samson would have worries about money. He would also have two small children, an erudite wife, an unsparingly candid schoolfriend, a vivacious sister-in-law and her long-suffering workaholic husband, with whom Bernard would share a dislike of his rich and pompous father-in-law. Bernard’s upbringing in Berlin would enable him to pass as a native but this achievement would not be greatly admired by his Whitehall superiors, who were to include a ruthless rival and an avuncular superior. And the story would depict them all as they grew older and weaker but not much wiser. Well, I wasn’t going to be able to cram that cast of characters into a normal-sized book. So I drew a large wall chart depicting the whole project, the main events in Samson’s life

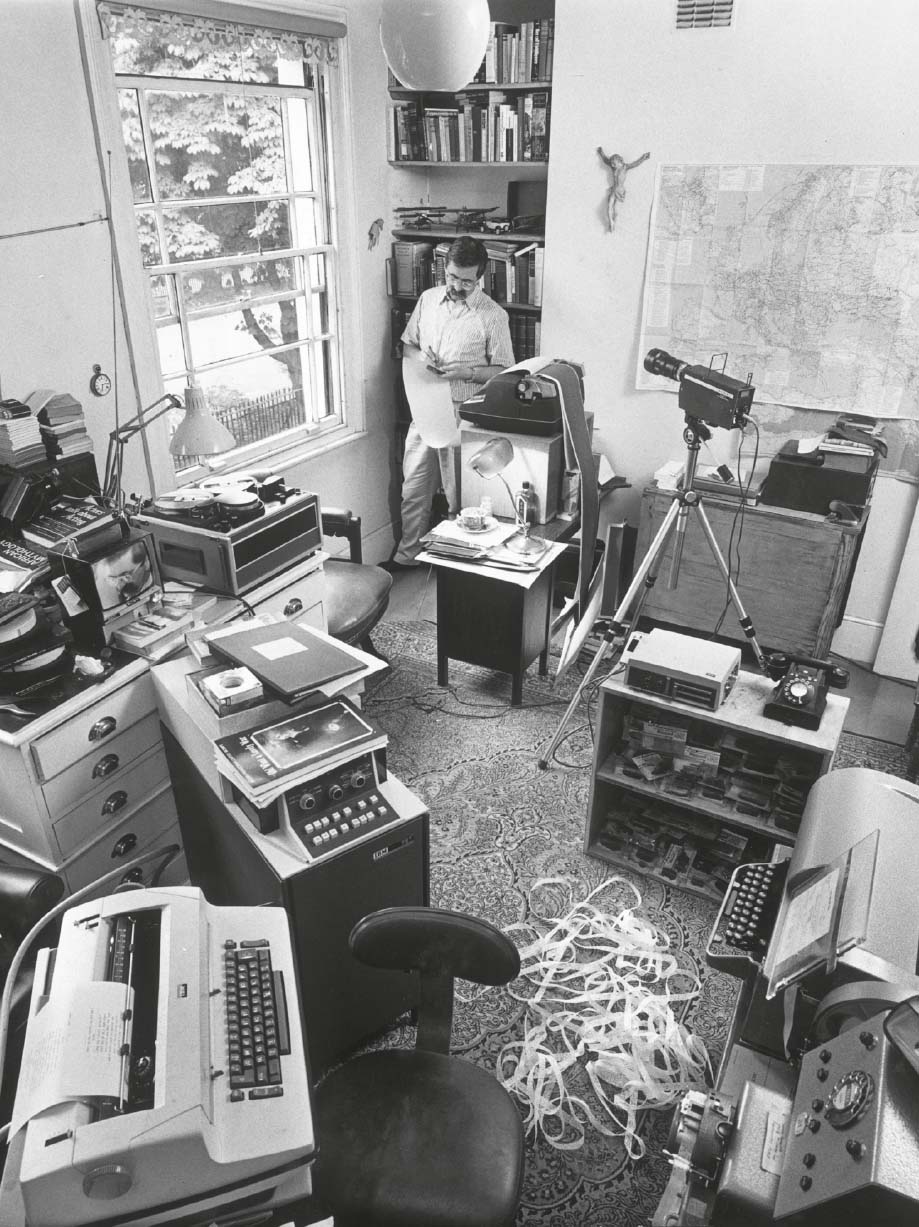

Me and my toys:

Starting in the bottom left corner there is the IBM 72 (the electric typewriter is a part of it). On it is my screenplay for Oh! What a Lovely War.

Beyond that there is a twin-spool video-recorder, then me, and the camera for the video recorder. To the right there is a teletape machine, used mostly for my travel pieces for Playboy magazine in Chicago, where I was the Travel Editor.

Next, I stared long and hard at my chart and started to divide it into book-length episodes. There would have to be two trilogies; no! three, as I incorporated Samson’s professional life. Would they be continuous? No. I would need time gaps and at some point in the series I might have to move from first person to third person in order to give the reader an overall view of the story.

Looking back on the writing of the nine ‘Samson books’ (ten if you include Winter, the prequel) my biggest regret is that I killed the sister-in-law far too early. She was a valuable character and the ongoing mystery of her death was not enough to compensate for her loss. I should have killed someone else. But there it is; we all make mistakes.