CHAPTER 13

A HEAP OF CONFUSION

I HELD ON TIGHTLY to the bottle of lavender salts, my single aim for the moment being to revive the ailing Miss Day. Hector and I raced up the gracious stairway to the open mezzanine that overlooked the Great Hall we’d just come from. The stairs stopped here, and we were already lost. Under Lucy’s leadership, we had mostly used the servants’ back stairs and wily ways through corridors that did not seem to adjoin this elegant gallery.

“What now?” I said.

“We want the East House,” said Hector. “Across the landing from where we are staying, yes? One of these doors must lead us there.”

“Which way is east?” I cried. “Are you carrying a compass?”

Hector leaned on the ornate railing and gazed at the leaded panes above the enormous front door below us. Pale morning light shone through, no doubt made brighter by the snow reflecting it, casting gentle shadows upon one wall.

“Voilà!” said Hector. “The sun, as always, is the best compass. It rises in the east and tells us now, from the direction of the shadows, which way to go.” He marched confidently to his chosen door at one end of the mezzanine, watched by the stone statue of a maiden holding a basket full of flowers.

We arrived in familiar territory only a few minutes later: the back stairs to the upper levels. Swinging around the final corner, thwack! I crashed headlong into a man! Hector ran smack into me, and for a moment, we made a jammed-up bundle of limbs.

“Whoa, there!” Mr. Mooney put his hands on my shoulders to steady me. Hector reeled against the wall.

“We’ve got the—” I showed him the bottle rather than finishing the sentence, as breath was difficult to find just then.

The actor pointed down the passage. “Third door,” he said. “Be quick.”

Kitty Sivam responded to our knock with a face of consternation. She took the bottle of salts and said her thanks, but closed the door quickly, without us having a chance to see anything beyond a glimpse of the actress lying on the bed with half-closed eyes.

“Well, that was disappointing,” I said, and Hector agreed.

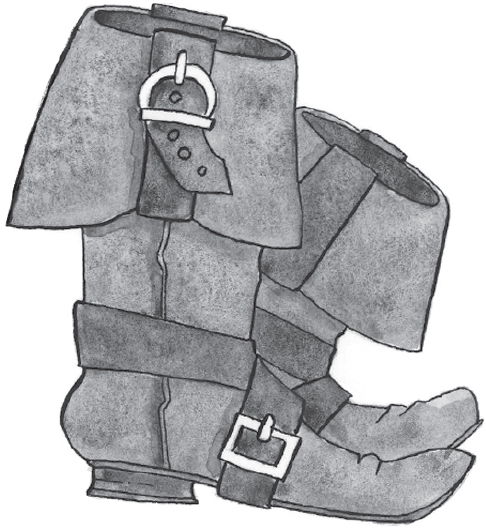

When we made our way down to the Great Hall, Lucy was waiting, manipulating one arm of a suit of armor forward and backward in a creaking salute.

“Finally!” she said. “Grandmamma didn’t want my company. She is beside herself, so vexed with the murderer for upending Christmas. Aunt Marjorie says we’re to have our Christmas luncheon early, in the kitchen with the servants before the guests eat upstairs. And we’ll have the actors too, though I suppose they mightn’t be too jolly. Aunt Marjorie doesn’t want children anywhere about when the police arrive. Strictly forbids us to be underfoot, is what she said.”

“Did you see Grannie Jane?” I said. “I’d like to go up—”

“Archer was just going in to help your grandmother dress, so you needn’t go up now. She waved at me, and said to tell you she’ll find you. Grandmamma is snarling about the police and her poor maid, Evelyn, has to listen. Pity us all when she comes down.”

The servants’ hall had been done up gaily, with red bunting looped above the doors and bits of evergreen tied with bows to the back of every chair.

“It’s a nuisance,” said Mrs. Hornby, when Lucy cooed about how pretty it looked. “But it raises up the spirits and that’s something. It’ll all be gone by tomorrow.”

A kitchen maid edged past with a tureen full of something that smelled rich and delicious, moving it from stove top to warming oven. She tried to bob a curtsy but her load made her off-balance.

“Don’t fret about us being Upstairs,” said Lucy, a bit grandly, I thought. “We’ll all muck in to help, since it’s not a proper Christmas.”

“ ‘Not a proper Christmas,’ she says!” cried Cook. “With a pirate lying dead in the library from what I hears.” But she told Dot to show us where to find the cutlery and told us how she liked the table laid. And she gave us paper crowns to give around and a butterscotch wrapped in foil for beside each place.

“I can’t find my gentleman.” Frederick came in with a tea tray. “I took this up in case he needed a cuppa, but he’s not there. Every drawer in the room is turned upside down.”

“Whatever next?” said Mrs. Frost. “I hope you tidied?”

“I did not,” said Frederick. “What if it was the robber and not Mr. Sivam who made the mess? The police might be interested.”

“You’ll get up there straightaway after you’ve eaten,” said Mrs. Frost. “I’m not having the Tiverton constabulary thinking we don’t keep things neat at Owl Park.”

And then a scullery girl named Effie nicked her finger on a knife and got Cook worried about blood in the creamed onions.

“They’re not meant to be pink!” she scolded.

Mr. Sebastian Mooney appeared with a smile and a wave to all. Hector and I traded a look. Wasn’t he a bit cheerful for a man whose friend was lying dead upstairs? And didn’t the cheeks of every maid in the servants’ hall turn as pink as berry cake at the sight of him?

Not Cook’s, though. “Humph,” she muttered. “Well, come in, Mr. Mooney. Word came down we’d have the actors joining us. Oh! Miss Day, up and about so soon? Feeling better?”

For someone who spent every waking hour in the kitchen, Cook seemed well informed as to any whisper of activity in all of Owl Park. Miss Day had followed Mr. Mooney through the baize door, looking a bit peaky but bright-eyed and upright, considering she’d been stricken on a bed only half an hour ago.

“I’m much better, thank you, Cook,” she said. “A bit of your marvelous food will restore me in no time. Oh, look!” She put on her gilt paper crown, and so did most of the rest of us.

“You’ll eat more than a bit, Miss Day, I hope,” said Cook. “You’re as thin as a book, you are.”

Miss Day flushed and protested. I supposed that Cook liked to see people grow round from eating her food, not lolling about looking wan and slim.

“I feel well enough,” said Miss Day. “We’ve just been wondering whether the police will let us head out.”

“We’ve got another engagement,” said Mr. Mooney. “Next Wednesday, New Year’s Eve.”

“We’d have to replace Roger, if we keep the booking,” said Miss Day. “It’s dreadful to think of.”

“The new hire will need to rehearse,” said Mr. Mooney. “We’re hoping for someone Roger’s size, so the costumes fit.”

There was an awful silence.

“That sounds a bit heartless,” said Miss Day. “But we need every shilling…No one hires actors after the holidays, so this is our last chance to make a little money. Weeks and weeks ahead of bread and soup for supper.”

The baize door had been opening and shutting, over and over again, as servants moved in and out. They couldn’t sit all together for meals, especially today, because the people upstairs needed tending to. But this time, the person coming in made Mrs. Frost get quickly to her feet. The other servants jumped up to show respect as well. Even Miss Day and Mr. Mooney, who weren’t servants.

“Goodness,” said Kitty Sivam. “You’re having a party.”

“No, no, madam, not really,” said Mrs. Frost.

Our paper crowns said otherwise, as did the table’s splendid feast. Mrs. Sivam must wonder how we could celebrate while a corpse lay upstairs and a priceless gem had been stolen from her husband’s bedchamber.

“How can I help, madam?” said Mrs. Frost. “Is there something you wanted?” Upstairs guests did not often come to the kitchen, her voice said. It was possibly even wrong, her being here. But the entire day was wrong, we all knew that. A corpse in the library was wrong.

Mrs. Sivam told everyone to please sit. Her voice trembled when she spoke.

“I can’t find my husband,” she said. Was she angry? Or fighting tears? “After all the upset…that poor actor, and the Echo Emerald missing…I haven’t seen Lakshay since he left the library. I thought…” She looked back and forth between the footmen, Frederick and John. “I thought one of you might have seen him?”

“I’m the one who’s assigned as his valet,” said Frederick, “only I was just up there to see if he needed anything, and he weren’t in his room. I’ve been worried where he might be.”

Mrs. Frost led her to a chair. “You sit for a minute, madam. Would you like some lunch? Or a cup of tea?”

Kitty shook her head, no tea, thank you, and she wouldn’t sit. But then she sat.

“I heard something,” said Stephen, “in the library, where you found the dead man.”

“Stephen,” said Mrs. Frost, sharply. “This is not the time for one of your ghost stories.”

“It weren’t a ghost,” said Stephen. “Ghosts do moaning and chain-rattling. But I never heard a ghost saying ‘dunderhead’ as loud as a minister talking, even being midnight. That, alongside having the wrong boots in odd places, it were a very peculiar night.”

“What do you mean by ‘wrong boots’?” I asked him.

But Mrs. Sivam had begun to shiver and Mr. Mooney half-stood, as if he might be required to assist another fainting woman.

“Ignore the boy, Mrs. Sivam, if you will,” said Mrs. Frost.

“Not to mention, a murder!” said Stephen, with a touch of glee in his voice.

Mrs. Frost raised a finger to warn him, and turned back to Mrs. Sivam.

“Are you certain you won’t have tea?”

“No, no thank you.” Mrs. Sivam looked pale and sick. She stared at Miss Day. “You’ve recovered quickly,” she said. Her eyes traveled to the shiny crown jauntily tilted on Miss Day’s auburn curls.

“Tip-top,” said Miss Day. “Thank you for watching over me.”

“And you?” said Mrs. Sivam to Mr. Mooney. “How are you feeling, about…Mr….”

Mr. Mooney did not meet her inquiring eyes. “Heartbroken,” he said simply.

Well, I knew what that felt like.

A bell chimed, and then again.

“That’s you, Frederick,” said Mrs. Frost, nodding up at the box fixed to the wall at the bottom of the stairwell. One circle on the display had turned green, indicating the need for a footman at the front door of the Great Hall.

“On my way.” Frederick pushed back his chair. He left his emptied plate on the table and reached for his jacket from its hook. The bell chimed again before he’d clicked the lever to show he’d heard.

“We’ve got all the modern touches here,” said Cook, flapping her hand at the bell box. “Ee-leck-tro-fried, that’s what I calls it. They rings a bell up there to tell who’s wanted, and off they go.”

Suddenly a crackle sounded from somewhere near the steps.

“Must be important if Mr. Pressman is using the speaking tube,” said Mrs. Frost.

The butler’s voice boomed. “His lordship is back. The police are making their way up the drive, on snowshoes. They will arrive shortly. Footmen up front please, and a groom to the stables. Put snowshoes and poles in the box room. Stand by for further instructions. I repeat, the police are here.”

The men pushed their plates aside and jumped to their feet. The maids gave them a quick look-over to make certain nothing was out of place.

Mrs. Sivam stood, seeming bewildered amidst the hubbub.

“Only the beginning,” sighed Mrs. Frost. “Police means snow and muck from their boots melting all over the floor. More buckets. More scrubbing. And men every which way!” Her fingers flew up to pat her hair and met the paper crown instead. “Wouldn’t that be a fine way to meet a detective?” She slid it off her head and onto the table.

“Look sharp,” she told the remaining staff. “We’ll all be wanted, one way or another.” She clipped her way up the stairs while the maids cleared the table and got on with their tasks.

“Thank you for a delicious lunch.” Annabelle, too, took off her paper crown and laid it on the table. “Having police come makes it horribly real,” she said. “Roger has been murdered.”

“I’ll speak with the detective in charge,” said Mr. Mooney. “Find out when he thinks we might move along.”

“We’ll likely have to cancel Inverness,” said Annabelle.

“I should think so!” said Mrs. Sivam, turning to rebuke before she went through the baize door. “One man killed and another missing, as well as a priceless emerald? None of us will be going anywhere.”

“No one cares about us, just for the moment,” I whispered to Hector and Lucy. “Let’s go back to the secret passage while we’ve got the chance. We can watch the police examine the body!”