CHAPTER 32

A CAUSE FOR ALARM

I CROSSED THE BUSY kitchen as if I hadn’t a care in the world, dodging the staff carrying platters for the upstairs luncheon. I pulled one of the servants’ shawls from a hook by the door, to use for the same reason they all did—an extra layer around neck and shoulders when going out to collect coal or eggs or bread or whatever next was needed from one of the outbuildings. I hoped to be collecting Hector.

Sergeant Fellowes, on guard duty for the corpse inside the stable, was chatting with three reporters who clustered at the doorway of the bakehouse.

Mr. Blake Cramshot from the Tiverton Bugle, Mr. Pockmark Dented Hat and…Mr. Augustus Fibbley of the Torquay Voice. Well, hello. Back so soon? Mr. Fibbley wore his dark peacoat and cap. His spectacles shone like twin mirrors in the glare of light from the snow.

“Have you seen my friend Hector, by any chance?” I asked them.

They shook their heads and shuffled their feet. I couldn’t bear to think how cold their feet must be. I hoped that Marjorie had given the baker permission to feed them warm bread. Should I pause to speak with Mr. Fibbley? Tell him how frantic I was about Hector? Should I say, Please help?

I thought back to what happened in October when I’d chased a villain by myself, and the frightful night that came as a result. A wave of icy recollection washed over me, sweeping away the notion that I might stand toe-to-toe with an angry man. Lucy was right. This was a task for the police. Hector would surely agree with Lucy. He wanted to be a policeman when he got older, so they could do no wrong in his opinion.

I glanced over at Sergeant Fellowes. I did not wonder that guarding a dead man might be boring, but he was now singing a duet with Mr. Cramshot, and was not the policeman in whom I wanted to confide. Inspector Willard had said I might inform him if Hector had not appeared by lunchtime. I’d sat next to him at breakfast and not mentioned that the murder weapon was in my bed. My fingers strayed to the bundle at my waist. I’d found the paper knife yesterday, and not yet told anyone.

The time had come.

I marched back inside and straight to the Avon Room. Constable Gillie stood at attention beside the door.

“One of the maids is in there just now,” he said.

Did that mean Mr. Mooney was in the coach house where I’d just been headed? Luck was on my side.

I’d found something the inspector would want to see, I told the constable. He followed me through the door and parked himself, straight and tall. I waited next to him. Our own Dot, under-parlormaid, was in the chair opposite Inspector Willard. On the table in front of him sat a plate from the kitchen holding a heap of gray muck. From where I stood, it looked like a macaroon gone terribly wrong.

Dot was in the middle of her story.

“Well, I says to her,” she said, “ ‘Scoff you might, Mrs. Frost,’ I says, ‘but of the forty-one grates I cleans each day, this be the only one with ashes what’ve got threads and bits of fabric and not just paper scraps and coal ash.’ ”

“I hope you did not sass the housekeeper so much as that,” said Inspector Willard, “but do go on, Miss Bolt. I’m listening.”

Dot’s shoulders rode up to her ears. “Well, anyway,” she said, after a moment’s sulk, “I showed her what I found, and she said that after all the police might want a gander. We put a sampling on this plate, what’s usually used for scones, and up I come to see you.”

Dot used the hem of her apron to wipe her face. “I’ve gone all perspiring.”

“Take your time,” said Inspector Willard. “We are keenly interested in what you have to say.”

Dot blinked two or three times, the freckles standing out on her cheeks.

“Whose grate were you cleaning, Miss Bolt,” said the inspector, gently, “when these threads and bits of blood-stained fabric emerged from the ashes?”

A day ago, Dot’s answer would have made the blood freeze in my veins, but now I guessed the name before she opened her mouth.

“Didn’t I say?” said Dot. “These bits has come from the grate in Mr. Mooney’s room. He hasn’t let me in there since Christmas, being ever so messy. It’ll take me all afternoon to scrub and tidy once he’s gone.”

“You won’t be expected to clean it,” said Inspector Willard. “The police will take care of that.”

“I’ve got the murder weapon,” I said, unable to wait another moment. “And Hector is still missing.”

Inspector Willard looked abruptly in my direction. The light sparked in his eyes as if I’d lit a match.

“Thank you, Miss Bolt,” he said to Dot. “You have been a great help. I shall commend you to Mrs. Frost.” Dot stood up and smoothed her apron. She smiled at me, a smile of triumph. A great help!

“Constable?”

The constable stiffened in anticipation of new orders. “Sir.”

“You will escort Miss Bolt to the kitchen. You will then locate Mr. Mooney and tell him that I’d like another word. If he objects, you will thump him. Go!”

As Constable Gillie hustled her out, Dot shot me another grin. This was the sort of action she could tell the servants’ hall!

Inspector Willard indicated that I should sit. I willed myself to meet his eyes.

“You are persistent,” he said. Did I discern the faintest twinkle or was that wishful thinking?

“Sir,” I said. My fingers closed around the lump inside the stocking at my waist.

“Please proceed,” he said, “even knowing that my focus is needed elsewhere.”

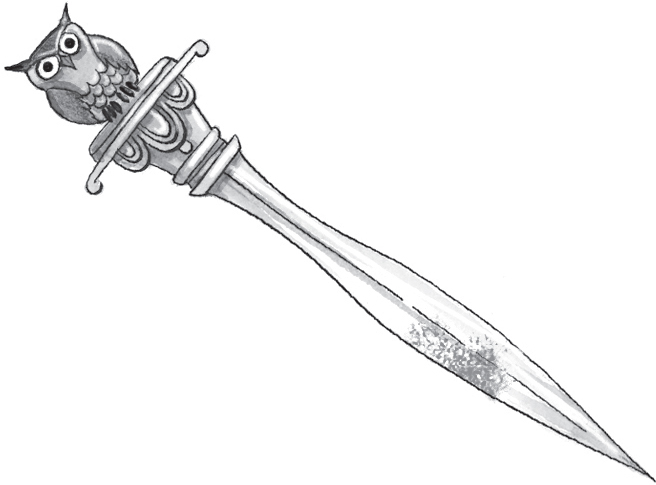

Goodness, yes. What was I hesitating over? Hector’s safety was in peril! I fumbled to untie the clumsy knot in the stocking and withdrew the paper knife. I placed it on the table between us. He picked it up to take a closer look.

“It’s from the desk in the library,” I said. “Sir.”

“Yes,” he agreed. “I recognize the owl.” The black streak caught his attention. His eyes darted to me and then back to the knife. For one-tenth of a second, he allowed a grin—but replaced it quickly with a wooden face.

“I will not ask how you came by this item from a guarded room during a murder investigation,” he said. “I’m beginning to suspect there is a secret passage in this old house. We have no time for that now. There is a chance that you have just presented a critical clue. One that you should not have. Having it means you are putting yourself in danger. I cannot allow—”

“But, Hector!” I said. “He’s still—”

He picked up the knife while shaking his head. “Please find your sister or your grandmother—or a book—and sit quietly for just a little while. We will get to the bottom of this.”

There came a tap at the door and Constable Gillie put his head in.

“We’ve got Mr. Mooney, sir. Sergeant Fellowes is here too, in case of trouble.”

“Thank you, Constable,” said Inspector Willard. “And thank you for your contribution, Miss Morton. Good day.”

Grrrrr!

The two policemen and Mr. Mooney filed into the Avon Room with no struggle, while I was marooned on the wrong side of the door. I’d delivered the murder weapon right into Inspector Willard’s hands! How could he be so cruel as to prevent me from watching its effect on the killer? If only the secret passage reached this far!

But wait!

A short bark of glee escaped before I clapped a hand over my mouth and pursued my brilliant idea. Lucy had shown us the wood cupboards that allowed the servants to resupply the log pile in each room without disturbing the family members within. And was I not standing in front of the Avon Room wood cupboard this very minute?

I checked that no one was in the passage before yanking open the tall narrow door. There were only a dozen logs stacked at the bottom, mostly against the other door, leaving enough room for a person to hoist herself up and squeeeeze sideways into the cupboard. I managed to shut the door but had to bend my neck rather awkwardly. The logs were knobby underfoot, but tightly packed and not at risk of rolling noisily about. It was the definition of uncomfortable, but I could hear nearly every word being spoken!

“Yes, he was drunk,” Mr. Mooney was saying. “But worse than that, he had in his hand the jewel that Mrs. Sivam had shown us all a few hours earlier.”

“Had he indeed?” said the inspector. “I’m sorry you did not provide this crucial detail during our first conversation, Mr. Mooney. How did you react to seeing that?”

“I confess I was very angry indeed,” said Mr. Mooney. His actorly voice carried nicely through the cupboard door. “There’d been a matter of a mislaid bracelet at another manor house we visited a few months ago. As roaming actors, we came under suspicion—a cloud we cannot afford to carry. I was furious that here seemed to be proof that my old friend was guilty of such low dealings.”

A moment’s pause.

I’d never thought to wonder whether the Echo Emerald was the first or only theft. Was our calamity just one in a chain of events?

“I’m afraid,” Mr. Mooney said, “that I used harsh words. I called him an idiot, and a dunderhead.”

But hadn’t he said last time that it was Mr. Corker who’d called him names?

“I told him,” said Mr. Mooney, “that his ongoing presence with the troupe was impossible. He’d put Annabelle and myself in a terrible situation.”

“And how did he respond?” asked Inspector Willard.

“He…he…” The actor paused again. “That’s when he hit me. My nose began to bleed.”

“This is the first I’ve heard of a bloody nose,” said Inspector Willard. “Another point withheld during our previous encounter.”

“Did I not mention that? I suppose I was embarrassed that a man ten years my senior managed to land a punch.”

“And did you hit him back?” said the inspector, coaxing.

“I did not.” Mr. Mooney sounded offended. “I gave him a push toward the chair. I had no intention of hitting a man so much the worse for drink. I told him again that we were finished and that he should be gone by morning. I didn’t care that he’d have to walk to Tiverton, is what I said, and maybe it would sober him up.”

Nearly a minute passed. I tried to turn my head to ease the crick, but my nose met the wall.

Then came a gulping noise before Mr. Mooney continued in a voice of deep regret. “I left the library. Because of the late hour, I went up the staircase from the Great Hall instead of using the servants’ steps. I heard a door open but hurried on, afraid to be noticed where I should not be. Thinking back, I assume it was Mr. Sivam, coming out of his room. He must have discovered the missing gem and gone to confront the thief.”

“Mr. Mooney.” The inspector’s tone was soft, almost confiding, meaning that I stopped breathing in order to hear properly. “Put yourself in my position for a moment,” he said. “What would you think if confronted by an intelligent man who lies to the police during a murder inquiry?”

No answer. Inspector Willard posed his next question.

“Why did you burn your shirt, if the blood was merely from your nose?”

I heard the clink of a dish and guessed that the plate of ashes had been pushed forward for Mr. Mooney to contemplate. I was impressed so far with Inspector Willard’s probing technique. His wording was careful, his pacing sure-footed, and his manner aloof but congenial. I had expected Mr. Mooney to be caught off-guard by the question about blood, but instead, he laughed!

“Ha! It saddens me to realize there is no woman in your life, Inspector! I live in fear of my colleague, Miss Annabelle Day. Of worrying or vexing her. Give her a bloodied shirt and confess the cause to be a dispute between her two best friends? I shudder to think of the outburst. Reason enough, I promise, to tear my shirt to shreds and burn away the evidence.”

We’d seen with our own eyes how particular Annabelle was about the costumes. Mr. Mooney’s wish to avoid making her cross was entirely wise. I paused to reconsider the whole of his testimony. What if everything he’d said was true, rather than false? How would that color our investigation? If only Hector were here to—

Hector!

Hector was not here! And this was my chance—while Mr. Mooney was occupied in police company—to have a quick look around the coach house! I backed up slowly on the uneven logs, pressing my perspiring palms against the sides of the cupboard. I bounced my heel against the door to nudge it open and eased myself to the ground. I had been confined for only a few minutes, but my joints seemed as creaky as Grannie Jane claimed hers to be. I smoothed my hair, shook wood chips from my skirt and set off at a run toward the kitchen.