The world has no instrument or means so pernicious as gunpowder, and capable of effecting such mischief.

THOMAS BARLOW

The Gunpowder Treason, 1679

TWENTY-FIFTH OF MARCH, KNOWN AS Lady Day in honour of the Feast of the Annunciation, was the date on which the new year started officially in the contemporary calendar.* It was a time of new beginnings, and on 25 March 1605 the Powder Treason took on a new dimension. It was considerably enlarged when Robert Wintour, John Grant and Kit Wright were let in to the secret. All three made strategic sense, continuing the feeling of family which pervaded the whole Plot. Not only was Robert Wintour of Huddington the elder brother of Thomas, but John Grant of Norbrook had married their sister Dorothy, and Kit Wright was the brother of Catesby’s close ally Jack.

John Grant, like Jack Wright, was a man of few words, with a general air of melancholy. But, unlike the famous swordsman Wright, Grant was something of an intellectual who studied Latin and other foreign languages for pleasure. Beneath the melancholy surface, however, and the air of scholarly withdrawal lay an exceptionally resolute character. Grant refused, for example, to be browbeaten by the local poursuivants, and defied them so often and so forcibly that they began to flinch from searching Norbrook (despite the fact that the house was more often than not sheltering Catholic priests). It was a steadfastness, based on a belief in God’s blessing on what he did, which John Grant ‘obstinately’ maintained to the very last.1

Crucial to John Grant’s admission, beyond his Wintour marriage and his own strength of purpose, was the geographical position of Norbrook. Grant’s house, near Snitterfield in Warwickshire, a few miles north of Stratford-upon-Avon, was excellently situated from the conspirators’ point of view. First, it belonged in the great arc of Plotters’ houses which now spread like a fan across the midlands of England: from Harrowden and Ashby St Ledgers near Northampton to Huddington and Hindlip by Worcester – not too far from the Welsh Marches, wilder terrain which offered a prospect of escape. It was vital to be able to evade searches by fleeing to a safe – or at least recusant – house. In the past priests had often been saved by making their way under cover of darkness to a neighbouring refuge until the search was over, and then returning when the coast was clear. One of Salisbury’s intelligencers referred to such elusive prey as having the cunning of foxes: ‘changing burrows when they smell the wind that will bring the hunt towards them’.2 The town which lay at the centre of this recusant map was Stratford-upon-Avon.

Grant’s house, Norbrook, was not far from Lapworth, the house where Catesby had been born and brought up, which now belonged to Jack Wright.3 Then there was the Throckmorton house, Coughton Court, a few miles to the west, owned by Catesby’s uncle Thomas but equally for rent if necessary since the Throckmorton fortunes were heavily depleted by recusancy. Baddesley Clinton lay to the east.

In order to understand how the midlands of England could constitute, with luck, a kind of sanctuary for recusants, it is necessary to project the imagination back to Shakespeare’s country (and Shakespeare’s native Forest of Arden) and away from the idea of an area dominated by the huge proliferating mass of today’s Birmingham, England’s second city. If Birmingham is removed from the mental map,† it will be seen that gentlemen could hunt (and plot) in this area, priests could take part in gentlemanly pursuits such as falconry, women could conduct their great households, including these priests as musicians or tutors, just so long as local loyalties remained on their side.

The reference to Shakespeare’s country is an appropriate one. We shall find the Gunpowder Plot providing inspiration in a series of intricate ways for one of Shakespeare’s greatest plays – Macbeth – and that again is not a coincidence. Stratford, celebrated as Shakespeare’s birthplace, was also the focus of his family’s life. The playwright’s father received a copy of The Spiritual Testament of St Charles Borromeo from Father Edmund Campion at Sir William Catesby’s Lapworth house. Shakespeare’s mother, from the recusant family of Arden, had property at Norbrook where John Grant lived and Shakespeare himself bought property at New Place in the centre of Stratford, in July 1605, in anticipation of his eventual retirement back to his birthplace.4

In London, the circles in which Shakespeare moved also meshed with those of the conspirators. This was the world of the Mermaid Tavern, where Catesby and his friends were inclined to dine and which was hosted by William Shakespeare’s ‘dearest friend’ (he witnessed a mortgage for him) William Johnson. This meshing had been true at least since the time of the Essex Rising, which had involved Shakespeare’s patron Lord Southampton, who went to prison for it, as well as Catesby, Jack Wright and Tom Wintour.

The figure of Sir Edward Bushell, who had worked for Essex as a Gentleman Usher, provided a further link – in this case a family one. Ned Bushell was a first cousin of the Wintours. As he admitted, the conspiracy included ‘many of my near kinsmen’: he would eventually become the guardian of young Wintour Grant, son to John Grant and Dorothy, which put him in control of Norbrook. But Bushell was also connected by marriage to Judith Shakespeare, the playwright’s daughter. Shakespeare’s familiarity with the environment of the Plotters both in London and in the country – and his own recusant antecedents – are certainly enough to explain his subsequent preoccupation with the alarming events of 1605, so many of which took place in ‘his country’.5

John Grant’s house at Norbrook had a further advantage since it was close to Warwick as well as Stratford. Horses – so-called ‘war-horses’ - would be an essential part of the coup. John Grant was to be in charge of their provision from the stable of Warwick Castle. War-horses of the continental type, strong, heavy ‘coursers’, about sixteen hands high, able to bear a man and his weaponry into battle, were rare in Tudor and post-Tudor England. The Spanish had blithely believed in their existence during the earlier invasion plans: but in fact the Tudors had tried in vain to breed this continental strain at home. The decent saddle horses of this time were Galloway ‘nags’ or native Exmoor ponies, a considerably smaller breed. When push came to shove – as it was expected to do – the ‘war-horses’ of Warwick Castle would be a valuable asset. The need for good horses of any type led directly to the induction of further conspirators later on in the year.

Finally, this natural focus on the midlands would, it was hoped, facilitate one of the plotters’ most important objectives. This was the kidnapping of the nine-year-old Princess Elizabeth.

The King’s daughter was housed at Coombe Abbey, near Coventry, not much more than ten miles north of Warwick and west of Ashby St Ledgers. Here, under the guardianship of Lord and Lady Harington, with her own considerable household, the Princess resided in state. If the little Prince Charles, with his frail physique, had disappointed the English courtiers, and Prince Henry, with his air of command, had enchanted them, Princess Elizabeth fulfilled the happiest expectations of what a young female royal should be like.

She was tall for her age, well bred and handsome according to a French ambassador who was eyeing her as a possible bride for the French Dauphin. (The canonical age for marriage was twelve, but royal betrothals could and did take place from infancy onwards.) The previous year she had already proved herself capable of carrying out royal duties in nearby Coventry. Following a service in St Michael’s Church, the young Princess had sat solemnly beneath a canopy of state in St Mary’s Hall and eaten a solitary dinner, watched by the neighbouring dignitaries.6 The Princess was therefore far from being an unknown quantity to those who lived locally – as royalties might otherwise be in an age without newspapers. On the contrary, the conspirators knew that she could fulfil a ceremonial role despite her comparative youth.

The ceremonial role which the Powder Treason Plotters had in mind was that of titular Queen.7 The location of the King’s nubile daughter was a critical element in their plans, for her betrothal was an immediate practical possibility and her marriage could be visualised within years. The Princess was currently third in succession to the throne, following her two brothers. But from the start it seems to have been envisaged that Prince Henry would die alongside his father (he had after all been markedly in attendance at all the state ceremonies of the two-year-old reign). On the subject of the four-year-old Prince Charles, the thinking was rather more confused. This was probably due to the fact that he was a latecomer to the royal scene. This, with his notorious feebleness (he had only just learnt to walk) made it difficult to read the part he would play at the Opening of Parliament. In the end the Plotters appear to have settled for improvisation in this, as in many other details.

If the little Prince Charles went to Parliament, then he would perish there with the others. If he did not, then it was Thomas Percy who was deputed to grab him from his own separate household in London. The birth of Princess Mary on 9 April 1605 introduced another potential complication. Although fourth in the succession to the throne, following her elder sister, the new baby had in theory the great advantage of being born in England. Remembering the xenophobia of Henry VIII’s will - foreign birth had been supposed to be a bar to the succession – there seems to have been some speculation about whether the ‘English’ Princess Mary was not a preferable candidate.8

The baby was given a sumptuous public christening at Greenwich on 5 May. Her tiny form was borne aloft under a canopy carried by eight barons. Her two godmothers were Lady Arbella Stuart and Dorothy Countess of Northumberland.‡9 But the talk about the baby, even the plans for the little Duke, do not seem to have had much reality, compared to the practical planning concerning the Princess Elizabeth.

In the total chaos which the ‘stroke at the root’ would inevitably bring about, the conspirators would need a viable figurehead and need him – or her – fast. No mere baby or small child would suffice. Princess Elizabeth, keeping her state in the midlands, was ideally placed for their purposes. As Catesby said, they intended to ‘proclaim her Queen’. Although a female ruler was never an especially desirable option, the memory of Queen Elizabeth, dead for a mere two years, sovereign for over forty, meant that it could scarcely be described as an unthinkable one. There was also the question of a consort, who might prove eventually to be the effective ruler: the Princess could be brought up as a Catholic in the future and married off to a Catholic bridegroom.10 (They were unaware – perhaps fortunately – that the Princess was completely unaffected by her mother’s romantic Catholicism and was already, at her young age, developing that keen Protestant piety which would mark her whole career.)

Such plans for a young girl did, however, pose the problem of an immediate overseer or governor. Once chaos had been brought about, a Protector would be needed urgently to restore order – and bring about those ‘alterations’ in religion which were the whole purpose of the violent enterprise.§11 Who was this Protector to be? The obvious answer was the Earl of Northumberland. At forty-one, he was a substantial and respected figure: the sort of man ‘who aspired, if not to reign, at least to govern’, in the words of the Venetian Ambassador.12 Northumberland was a Catholic sympathiser, and Thomas Percy, one of the chief conspirators, was both his kinsman and his employee. Compared to Northumberland, none of the overtly Catholic peers – not the outspoken Montague, not Stourton, not Mordaunt – because of their long-term depressed position as recusants, had the necessary stature. As for that untrustworthy Church Papist from the past, Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton, age was creeping up on him – he was sixty-five. His main Catholic activity these days was trying to persuade the King to have a splendid monument made to Mary Queen of Scots in Westminster Abbey (she was currently buried in Peterborough Cathedral in modest conditions which dissatisfied the aesthetic Earl).

It would certainly have made sense for the conspirators to reach a decision in Northumberland’s favour and, having made it, to alert him via Percy in some discreet fashion, if only to prevent his attendance at the fatal meeting of Parliament. Yet, curiously enough, the conspirators do not seem to have made any final decision on the subject. Once again there was an area of improvisation in their plans. Certainly, Northumberland’s behaviour around the crucial date in early November, which will be examined in detail in its proper place, gives no hint that he had been alerted to his glorious – or inglorious – destiny. Guy Fawkes never gave any information on the subject, presumably because he had none to give. Tom Wintour denied any knowledge of ‘a general head’.13

Father Tesimond’s explanation to Father Garnet, that the choice of the Protector was to be ‘resolved by the Lords that should be saved’, is probably the true one. And who these would be no one of course knew for certain in advance. As Father Tesimond added: ‘They left all at random.’ This was indeed the line taken by Coke at the trial: the Protector was to be chosen after the ‘blow’ had taken place from among those nobles who had been ‘reserved’ by being warned not to attend Parliament – a clever line to take, since it left open the important question of who had been warned and who had not.14 In short, the same policy was pursued as with the members of the Royal Family: they would wait and see who survived, with Northumberland as the front-runner.

Under the circumstances, there was a certain unconscious irony in an allusion to Princess Elizabeth made by King James in the spring of 1605. Increasingly he was venting his spleen on the subject of the Papists, who had been ‘on probation’ since his accession. Now he was irritated by their refusal to recognise how truly well off they were under his rule. Why could they not show their gratitude by remaining a static, passive community? John Chamberlain heard that King James had ranted away along the lines that, if his sons ever became Catholics, he would prefer the crown to pass to his daughter. In the meantime the recusancy figures were rising. As the Venetian Ambassador reported in April, the government was now beginning to use ‘vigour and severity’ against the Catholics.15

Some English Catholics were still exploring the option of ‘buying’ toleration with hefty amounts of cash, possibly obtained from Spain, and came to talk to the envoy Tassis about it. Meanwhile Pope Clement VIII, who died in the spring after a seventeen-year Papacy, went to his grave still believing in the imminent conversion of King James to Catholicism. In part this was due to the diplomatic manoeuvres of a Scottish emissary in Rome, Sir James Lindsay, whether sincere or otherwise; in part it sprang from the soulful communications of Queen Anne, which were certainly sincere but not necessarily accurate.16 From the point of view of the conspirators, however, both hopes were equally unrealistic. ‘The nature of the disease required so sharp a remedy,’ Catesby had told Tom Wintour, pointing to the need for terrorism. A year further on, plans to ‘do somewhat in England’ were at last taking practical shape.

Twenty-fifth of March, the date on which the new Plotters were admitted, was also the date on which a lease was secured on a so-called cellar, close by the house belonging to John Whynniard. This house itself, it must be emphasised, was right in the heart of the precinct of Westminster: and yet there was nothing particularly exceptional about that. The Palace of Westminster, at this date and for many years to come, was a warren of meeting-rooms, semi-private chambers, apartments – and commercial enterprises of all sorts.‖ The antiquity of much of the structure helped to explain its ramshackle nature. There were taverns, wine-merchants, a baker’s shop in the same block as the Whynniard lodging, booths and shops everywhere. In short, modern notions of the security due to a seat of government should not be applied to the arrangements at Westminster then.

The Whynniard house in 1605 lay at right angles to the House of Lords, parallel to a short passageway known as Parliament Place. This led on to Parliament Stairs, which gave access to the river some forty yards away. There was also a large open space bordering on the Thames known as the Cotton Garden. One authority has compared the plan of the relevant buildings ‘for practical purposes’ to the letter H.17 If an H is envisaged, the House of Lords occupied the cross-bar on the upper floor, with a cellar beneath. The left-hand block consisted of the Prince’s Chamber, used as a robing-room for peers, on the same level as the House of Lords; Whynniard’s house, and the lodging of a porter, Gideon Gibbon, and his wife, lay below it. The right-hand block housed the Painted Chamber, used as a committee room, on the upper floor.

Most houses of the time had their own cellar for storing the endless amount of firewood and coals required for even the most elementary heating and cooking. The cellar belonging to Whynniard’s house was directly below the House of Lords and it seems to have been part of the great mediaeval kitchen of the ancient palace. However, this area, which was to become ‘Guy Fawkes’ cellar’, where in the popular imagination he worked like a mole in the darkness, was actually on ground level. It might, therefore, be better described as a storehouse than a cellar. Over the years it had, not surprisingly, accumulated a great deal of detritus, masonry, bits of wood and so forth, which quite apart from its location made the ‘cellar’ an ideal repository for what the conspirators had in mind. It had the air of being dirty and untidy, and therefore uninteresting and innocuous.18

Just as the cellar was really more of a storehouse, the house, on the first floor, was so small that it was really more of an apartment. Certainly two men could not sleep there at the same time. Thus while Guy Fawkes, alias John Johnson, was ensconced there, Thomas Percy used his own accommodation in the Gray’s Inn Road. A convenient door from the lodging – which, it will be remembered, was leased in the first instance to Whynniard as Keeper of the King’s Wardrobe – led directly into the House of Lords at first-floor level. This meant that it could be used on occasion as a kind of robing-room, and even for committee meetings (the shifting employment of the rooms around the Palace of Westminster for various purposes demonstrates the casual nature of the way it was run).a

Thomas Percy’s excuse for needing this ‘cellar’ – so crucially positioned – was that his wife was coming up to London to join him. Mrs Susan Whynniard appears to have put up some resistance on behalf of a previous tenant, a certain Skinner, but in the end money talked: Percy got the lease for £4, with an extra payment to Susan Whynniard. A Mrs Bright who had coals stored there was probably paid off too.19 Using the customary access from the river (with its easy crossing to Lambeth – and Catesby’s lodgings – on the opposite bank) a considerable quantity of gunpowder was now transported to the cellar over the next few months.

Guy Fawkes revealed that twenty barrels were brought in at first, and more added on 20 July to make a total of thirty-six. According to Fawkes, two other types of cask, hogsheads and firkins, were also used, with the firkins, the smallest containers, generally employed for transport. While there would be some divergence in the various other accounts of exactly how much gunpowder was transported and when – between two and ten thousand pounds has been estimated – the amount was generally agreed to be sufficient to blow up the House of Lords above the cellar sky high.b20

The gunpowder was of course vital to the whole enterprise. As Catesby and his companions lived in an age when the deaths of tyrants (and of the innocent) were observable phenomena, they were also familiar with the subject of gunpowder, and explosions caused by gunpowder. Although the government had a theoretical monopoly, it meant very little in practical terms. Gunpowder was part of the equipment of every soldier: his pay was docked to pay for it, which encouraged him to try and make the money back by selling some under cover. The same was true of the home forces – the militia and trained bands. Similarly every merchant vessel had a substantial stock. Proclamations on the part of the government forbidding the selling-off of ordnance and munitions, including gunpowder, show how common the practice was.

In any case, the Council encouraged the home production of gunpowder in the last years of Elizabeth’s reign. There were now powdermills at various sites, many of which were around London, including Rotherhithe, Long Ditton in Essex, Leigh Place near Godstone, and Faversham. In 1599 powdermakers were ordered to sell to the government at a certain price, while any surplus could go to merchants elsewhere at threepence more in the pound. The diminution of warfare and the disbandment of troops in the context of the Anglo-Spanish peace meant that there was something like a glut. Access was all too easy, so that anyone with a knowledge of the system and money to spend could hope to acquire supplies. Furthermore, conditions of storage were alarmingly lax. Although powder was supposed to be kept in locked vaults, it was often to be found lying about, as official complaints to that effect also demonstrate.21

When two Justices of the Peace for Southwark had gone to search the London house of Magdalen Viscountess Montague in 1599, it was significant that they had been looking for gunpowder. They reported that it was supposed ‘to have been lately brought hither’, but although they searched ‘chamber, cellar, vaults’ diligently their efforts met with no success. (Either the gunpowder was well hidden – like the many priests this distinguished recusant habitually concealed – or the Justices were acting on false information.)22 The formula for gunpowder mixed together sulphur, charcoal and saltpetre, which by the end of the fifteenth century were, with added alcohol and water, being oven-dried and broken into small crumbs known as ‘corned-powder’. In this form gunpowder was used for the next four centuries. In many ways it was the ideal substance for explosive purposes. It was insensitive to shock, which meant that transport did not constitute a problem, but was extremely sensitive to flame.c23

The Plotters might have been original in the daring and scope of their concept, but they were certainly not original in choosing gunpowder to carry out the ‘blow’. In 1585 five hundred of the besiegers of Antwerp had been killed by the use of an explosive-packed machine, invented by one Giambelli. Then there were accelerated explosions, comparatively frequent, testifying to the lethal combustion which the material could cause. To give only one example, there was an enormous explosion on 27 April 1603 while the King was at Burghley. This took place at a powdermill at Radcliffe, near Nottingham, not many miles away. Thirteen people were slain, ‘blown in pieces’ by the gunpowder, which ‘did much hurt in divers places’.24

There was only one problem: gunpowder did, after a period of time, ‘decay’ – the word used. That is to say, its various substances separated and had to be mixed all over again. ‘Decayed’ gunpowder was useless. Or to put it another way, decayed gunpowder was quite harmless, and could be safely left in a situation where it might otherwise constitute an extraordinary threat to security.

While the logistics of the ‘blow’ were being worked out, foreign aid in the form of majestic Spanish coursers and well-trained foreign troops to supplement the slightly desperate cavalry which would be constituted by the English recusants was still the desired aim. Guy Fawkes went back to Flanders to swap being John Johnson for Guido again, where he tried to activate some kind of support in that familiar hotbed of Catholic intrigue and English espionage. About the same time, the grand old Earl of Nottingham set off for Spain to ratify the treaty. Approaching seventy, Nottingham (yet another Howard) had been married to Queen Elizabeth’s first cousin and close friend whose death had set off her own decline. However, age had not withered Nottingham, since he had quickly remarried into the new dynasty: a girl called Margaret Stewart, kinswoman of the new King. Unfortunately Guido and his colleagues did not share the same appreciation of diplomatic and dynastic realities as this great survivor.

At some point in this trip, Fawkes’ name was entered into the intelligence files of Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury. The King’s chief minister had of course an energetic network of spies everywhere, not only in Flanders but in Spain, Italy, Denmark and Ireland. Furthermore, Salisbury was able to build on the famous Elizabethan network of Sir Francis Walsingham. The number of ‘false’ priests abroad – treacherous intriguers who either were or pretended to be priests – constituted a specially rich source of information, as Salisbury admitted to Sir Thomas Parry, the Ambassador in Paris. They were all too eager to ingratiate themselves with such a powerful patron. The rewards could include permission to return to England for one who actually was a priest or straightforward advancement for one who was not. In the autumn of 1605 George Southwick (described as ‘very honest’ – which perhaps from Salisbury’s point of view he was) returned to England in the company of some priests he had secretly denounced. The plan was that he should be captured with them, so as to avoid suspicion.25

After the official – and dramatic – discovery of the Plot, there would be no lack of informants to put themselves forward and claim, as did one Thomas Coe, that he had provided Salisbury with ‘the primary intelligence of these late dangerous treasons’. Not all these claims hold water: Southwick for example was still busy filing his reports about recusant misdeeds on the morning of 5 November, with a manifest ignorance of what was to come.26 The person who seems to have pointed the finger of suspicion at Guido Fawkes – and even he did not guess at the precise truth – was a spy called Captain William Turner.

Turner was not a particularly beguiling character. He was heartily disliked by the man on the spot, Sir Thomas Edmondes, Ambassador to Brussels, who considered him to be a ‘light and dissolute’ rascal, someone who would say anything to get into Salisbury’s good books. Rascal or not, Turner certainly had a wide experience of the world, having been a soldier for fourteen years, in Ireland and France as well as the Low Countries. His earliest reports on the Jesuits had been in 1598. Now he filed a report, implicating Hugh Owen (always a good name to conjure with where the English government was concerned) in a planned invasion by émigrés and Spanish, to take place in July 1605.27

There was, however, no mention of the conspiracy which would become the Powder Treason. Moreover, when Turner went on to Paris in October and passed papers to the English Ambassador there, Sir Thomas Parry, about ‘disaffected [English] subjects’ he still knew nothing of the projected ‘blow’. Parry, however, took his time in passing all this on. Turner’s report on the dangerous state of the stable door did not reach England until 28 November, over three weeks after the horse had bolted. In essence, Turner’s information belonged to a diffused pattern of invasion reports, rather than anything more concrete.28

Nevertheless, Turner had picked up something, even if he had not picked up everything. In a report on 21 April, he related how Guy Fawkes – who was of course a well-known figure in the Flemish mercenary world – would be brought to England by Father Greenway (the alias of Father Tesimond). Here he would be introduced to ‘Mr Catesby’, who would put him in touch with other ‘honourable friends of the nobility and others who would have arms and horses in readiness’ for this July sortie.29 There are clear omissions here. Invasion reports had been two a penny for some time – as, for that matter, had unfulfilled plans for such an invasion, including those of Wintour and Fawkes himself. Apart from the specific lethal nature of the Powder Treason (which we must believe Turner would have relished to reveal, had he known it) Guy Fawkes’ alias of John Johnson is missing, which is an important point when we consider that he was not about to leave for England, but had been installed as Johnson in a Westminster lodging for nearly a year. Yet Turner had established Guy Fawkes, if not John Johnson, as a man to be watched and he had connected his name to Catesby’s – already known as one of the Essex troublemakers – and to that of Greenway/Tesimond. This information must have taken its place in the huge mesh of other reports which Salisbury received, even if its significance was not immediately realised.

Elizabeth I with Time and Death: towards the end of her life, Queen Elizabeth fell into a profound melancholy, underlined by the deaths of her old friends. (ill. 8.1)

James I by an unknown artist: King James was thirty-six when he ascended to the English throne. The English found him at first encounter to be affable and ‘of noble presence’. (ill. 8.2)

Accession medal of James I, as emperor of the whole island of Britain: the King (unlike the English courtiers) was enthusiastic about the concept of ‘Britons’. (ill. 8.3)

Anne of Denmark by Marcus Gheerhaerts the Younger, c. 1605–10: there had not been a Queen Consort in England since the days of Henry VIII. The King’s gracious wife was welcomed by the crowds. (ill. 8.4)

Henry Prince of Wales and Sir John Harington by Robert Peake, 1603: the handsome young heir to the throne won golden opinions, a Royal Family being a new phenomenon in England. (ill. 8.5)

Charles Duke of York (the future Charles I) as a child by Robert Peake: unlike his athletic elder brother, Charles was physically frail and only learned to walk at the age of four. (ill. 8.6)

The monuments in Westminster Abbey to two daughters of James I, Mary and Sophia, who died young: Princess Mary, who was born in England in 1605, was considered by some to have a better claim to the throne than her elder siblings born in Scotland. (ill. 8.7)

Princess Elizabeth (the future Elizabeth of Bohemia) by Robert Peake: the charm and dignity of this nine-year-old girl, who held a little court in the midlands, encouraged the conspirators to think she might make a suitable puppet Queen. (ill. 8.8)

Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia by Franz Pourbus the Younger, c. 1599: some Catholics hoped that this Habsburg descendant of John of Gaunt – co-Regent, with her husband, in the Spanish Netherlands – would be backed by military force to succeed to the English throne. (ill. 8.9)

Arbella Stuart by an unknown artist, 1589: the first cousin of King James, with both Tudor and Stuart blood, but brought up in England, Arbella was a possible contender for the throne. (ill. 8.10)

Both Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare had connections to Catholics on the periphery of the Gunpowder Plot; Macbeth contains allusions to the fate of the ‘equivocating’ Jesuit, Henry Garnet. (ill. 8.11) and (ill. 8.12)

This engraving shows eight of the thirteen conspirators: missing are Digby, Keyes, Rookwood and Tresham. (ill. 8.13)

Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland, by Van Dyck: although Northumberland’s actual involvement in the plot remains controversial, he was fined heavily and sentenced to prolonged imprisonment as a result. (ill. 8.14)

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, attributed to John de Critz: equipped with a prodigious intellect, and a capacity for hard work, Salisbury was short and physically twisted at a time when the outer man was often thought to be a key to his inner nature. (ill. 8.15)

Sir Everard Digby: the darling of the court for his handsome looks and sweetness of character, Digby’s fate caused universal consternation even among those who condemned him. (ill. 8.16)

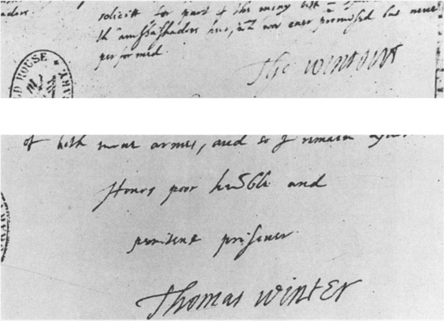

Two contrasted signatures by Thomas Wintour: one indubitably his, in the habitual form in which he signed his name; the other, using a different spelling, on his so-called ‘Confession’, possibly forged by the government. (ill. 8.17)

Turner’s alarm about a July invasion-that-never-was leads on to the far more crucial question of who knew about the Powder Treason in England. For it was in England, where the conspiracy was actually being hatched, that betrayal was infinitely more likely to take place.

Who knew? First of all, there were the servants, that ever present body of the ‘inferior sort’, in the Privy Council’s dismissive phrase, which nevertheless all through history has had unrivalled opportunities for keyhole knowledge. The hierarchical nature of society meant that servants nearly always followed the views of their masters with fanatical loyalty, since they would probably be casually condemned for them anyway (witness the number of servants, like Robert Grissold of Lancaster, who died with their masters, the priests). Then there was that other body, the faithful Catholic gentlewomen of recusant England, the women already trusted with the lives of their pastors, the wives and close relations of the conspirators. There must be a strong presumption that, in whispers conducted in corners, in veiled allusions in innocent domestic correspondence, the news spread.

At Easter 1605, a very odd incident had taken place involving Eliza Vaux which was never satisfactorily explained.30 (It goes without saying that the conspirators’ wives, notably the admirable Gertrude Talbot Wintour of Huddington, would deny having any scrap of foreknowledge, but with a family’s future at stake such a denial may not have represented the whole truth; what a wife knows privately about her husband’s plans is in any case unquantifiable.) Eliza Vaux herself was at this time properly concerned with her duty to marry off her eldest son Edward, 4th Baron Vaux of Harrowden, who was seventeen. Lord Northampton, who took on the duty of arranging a suitably worldly match, selected Lady Elizabeth Howard, one of the numerous daughters from the brood of his nephew the Earl of Suffolk and the avaricious but beautiful Catherine.

Lady Elizabeth Howard was on paper an excellent choice. She was well connected due to her parents’ position at court and, like all the Howard girls, she was extremely pretty. It is clear from what happened afterwards that the young Edward Vaux fell deeply in love with her. Unfortunately the advantageous marriage hung fire, and Eliza Vaux, getting increasingly impatient at the delay, correctly assessed the reason. It was because she and her son were both considered to be ‘obstinate Papists’.

Eliza had a close woman friend, Agnes Lady Wenman, who was the daughter of Sir George Fermor of Easton Neston, not so far away from Harrowden, and yet another cousin of the family (her grandmother had been a Vaux). Since her marriage Agnes Wenman had lived at Thame Park, near Oxford. Eliza Vaux expected to get a sympathetic hearing from Agnes on the subject of the delayed match, not least because she had influenced her friend in the direction of Catholicism during Sir Richard Wenman’s absence in the Low Countries, or, as that gentleman preferred to put it, Eliza Vaux had ‘corrupted his wife in religion’. Father John Gerard himself taught Lady Wenman how to meditate, and she began to spend up to two hours a day in spiritual reading. At Easter – 31 March – Eliza Vaux indiscreetly confided to Agnes Wenman in a letter that she expected the marriage would soon take place after all, since something extraordinary was going to take place.31

‘Fast and pray,’ wrote Eliza Vaux, or words to that effect, ‘that that may come to pass that we purpose, which if it do, we shall see Tottenham turned French.’ (This was contemporary slang for some kind of miraculous event.) What Eliza Vaux did not expect was that this letter would be opened in Agnes Wenman’s absence by her mother-in-law Lady Tasborough. The latter, who interpreted the reference as being to the arrival of Catholic toleration, showed the letter to Sir Richard. Even though he remembered the phrase slightly differently – ‘She did hope and look that shortly Tottenham would turn French’ – the hint of conspiracy was salted away in his mind. The letter itself vanished before November, leaving Eliza to take refuge in the traditional excuse of a blank memory. She claimed she had no recollection of the phrase or what she meant by it.32

Tottenham did not turn French, and the compromising Wenman letter was exposed only by chance, aided perhaps by the malice of a mother-in-law. It conveys, however, in a private communication from one woman to another, an atmosphere of excitement and Catholic hope, even if its precise meaning remains mysterious. (But it is surely unlikely that the reference was to toleration, given the Anglo-Spanish situation.) How many other hints were dropped at this period can only be suspected, given that in the dreadful aftermath of 5 November such incriminating letters would, where possible, have been quickly destroyed.

There was, however, a third body in England, beyond the mainly silent servants and the mainly discreet gentlewomen, who might on the face of it have known about the Plot and remained quiet on the subject. These were the hidden, watchful priests. At the beginning of the summer, Father Henry Garnet reported unhappily to Rome that the Catholics in England had reached ‘a stage of desperation’ which made them deeply resentful of the ongoing Jesuit commands to hold back from violence.33 At this stage, he too was acting on suspicion rather than direct information.

Meanwhile, the secret Catholic community tried to maintain those rituals which were so precious to it. One of the chief of these was the Feast of Corpus Christi (the Blessed Sacrament) following Trinity Sunday, celebrated this year on 16 June. Although instituted comparatively recently in ecclesiastical terms, it had become a great feast of the late mediaeval Church, involving a procession, banners and music. All of these things were far more conspicuous, and thus difficult to conceal, than a Mass said in an upper room at 2.00am (a popular hour for the Mass, when it was hoped that the searchers would not intrude). This particular Corpus Christi was celebrated at the home of Sir John Tyrrel, at Fremland in Essex. Involving ‘a solemn procession about a great garden’, it was watched by spies, although the priests managed to get away safely afterwards.34 What the spies did not know was that a week earlier Father Garnet had found himself having a conversation, seemingly casual, yet uncomfortably memorable all the same, with his friend Robin Catesby.

The conversation took place in London on 9 June, at a room in Thames Street, an extremely narrow lane which ran parallel with the river west from the Tower of London. In the course of a discussion concerning the war in Flanders, Robin Catesby threw in an enquiry to do with the morality of ‘killing innocents’. Garnet duly answered according to Catholic theology. It was a case of double-effect, as Garnet propounded it to Catesby. In ending a siege in wartime ‘oftentime … such things were done’: that is, the assault which ended it would result in the capture of an enemy position, but at the same time it might cause the death of women and children. From Catesby to Garnet, there was certainly no mention of ‘anything against the King’, let alone gunpowder. As Garnet confessed later concerning Catesby’s enquiry: ‘I thought the question to be an idle question’: if anything, it referred to some project Garnet believed Catesby entertained, to do with raising a regiment for Flanders.35

If we accept Garnet’s version to be the truth, then he was still in genuine ignorance of any specific design when Father Tesimond sought him out in the Thames Street room, shortly before 24 July. Oswald Tesimond was a lively northerner whose bluff appearance – his ‘good, red complexion’, black hair and beard – owed something to these origins. But Tesimond, who had been trained in the English College in Rome, after years abroad was now a sophisticated fellow, as indicated outwardly by the fact that his clothes were ‘much after the Italian fashion’.36 He had been back in England for about seven years. An intelligent and thoughtful man, he was a great admirer of the calm wisdom of the Superior of the English Jesuits, Father Garnet.

What he now told Garnet could in no way be shrugged off as ‘idle’. For Father Tesimond had recently heard the confession of Robin Catesby. In a state of extraordinary distress, Tesimond now sought out his Superior in order to share the appalling burden of what he had heard. Like Catesby, he proposed to impart what he had to say under the seal of the confessional.

* 1 January was not employed until 1752; although it is used in the dating of this narrative to avoid confusion.

† It was a small market town of some fifteen thousand inhabitants as late as 1700 and began to develop only in the late eighteenth century.

‡ The day before, letters patent were issued to transform Robert Cecil, currently known as Viscount Cranborne, into the Earl of Salisbury, the name by which he will henceforth be known.

§ The office of Protector was a familiar – if not exactly popular – one in English history from the reign of Edward VI who succeeded to the throne at nine; while Scotland under King James, crowned king at thirteen months, had needed a series of regents.

‖ The diaries of Pepys, sixty years on, bear ample witness to the success of these enterprises: Westminster Yard was a favourite rendez-vous, where he shopped for prostitutes among other goods on offer.

a The Palace of Westminster was redesigned in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, following the fire of 1834. Fortunately William Capon, an enthusiast for architectural research, had made an elaborate survey of the old palace in 1799 and 1823, illustrating it with a map which was eventually acquired by the Society of Antiquaries (see this page).

b There can be no doubt that a substantial amount of gunpowder was placed in the ‘cellar’, as the recent publication of the official receipt for it, on its return to the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London, has demonstrated (Rodger, pp. 124–5).

c With elements of potassium, nitrogen, oxygen, carbon and sulphur making it up, gunpowder ignited at between 550 and 600 degrees Fahrenheit.