EPILOGUE

A National Blue Ocean Shift in Action

WITH NATIONS AROUND THE world facing tight budgets and growing demands from their citizens, blue ocean shifts are as applicable for governments as they are for corporations, nonprofits, or start-ups. In this epilogue, we’ll draw on the experience of Malaysia to illustrate a national blue ocean shift in action, discuss the issues it is addressing, how the process works, and the far-reaching results it has produced.

In the beginning of the new millennium, Malaysia was at a crossroads, stuck in the so-called middle-income trap. During the 1970s, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan had all been at a similar level of development, but that was no longer the case. In the intervening years, the other three countries had all become high-income nations, but Malaysia had not managed to make the jump. The country was facing differentiation challenges from developed nations and regions like the United States, Europe, and Japan, which offered higher quality, and low-cost challenges from emerging countries like China, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

Malaysia’s leaders wanted to move the country out of this red ocean trap and thought that blue ocean strategy might provide the platform for achieving greater public well-being and higher national income. To test and validate their reasoning, the prime minister and the deputy prime minister invited us to engage in several rounds of discussions with different interest groups, ranging from informal small group sessions, to a three-day retreat with national leaders from the public and private sectors, to an official cabinet meeting chaired by the prime minister. After two years of exploration and probing, the government decided to apply the theory and tools of blue ocean strategy to create blue ocean shifts in the nation’s economic and social sectors.

To this end, the government set up a nonprofit research organization, called the Malaysia Blue Ocean Strategy Institute (MBOSI), in 2008. The following year, it launched the National Blue Ocean Strategy Summit, an ongoing monthly gathering of Malaysia’s top national leaders, its highest-ranking civil servants, including those from the nation’s security forces, and selected leaders from the private sector. When the agenda doesn’t require the direct attention of the prime minister or the deputy prime minister, the chief secretary to the government chairs the Summit gatherings. To ensure that the principles and process of blue ocean shift are properly applied, MBOSI has supported the Summit from the start.

By January of 2013, the National Blue Ocean Strategy Summit (hereafter referred to as the NBOS Summit) had launched more than 50 economic and social blue ocean shift initiatives. For these initiatives, differentiation was conceptualized in terms of delivering a leap in value, or high impact, to the country’s economy and society, while low cost was defined in terms of the savings generated by reductions in the cost of providing government services. Since the public sector is notoriously slow, the speed of execution was added as the third measure of a successful shift, making the guiding principles of every NBOS initiative high impact, low cost, and rapid execution.

Following the successful outcomes of these initiatives and the rapid expansion of their scale and scope, the government established the National Strategy Unit under the Ministry of Finance to further support, accelerate, and monitor the initiatives in close cooperation with MBOSI. By 2017, the number of blue ocean initiatives launched at the national level totaled over 100.

How National Blue Ocean Initiatives Are Formulated and Executed

National transformation programs often fail because government organizations are unable to overcome deeply entrenched silos. With government ministries, departments, and agencies typically working in isolation, resources and information are seldom shared, and turf wars and lack of ownership are all too common. The NBOS Summit recognized that blue oceans could not be created unless these silos were broken down and the boundaries separating federal, state, and local government officials were dissolved. By encouraging people in these different silos and levels to work together and share their knowledge and resources, based on the tools and process driving a blue ocean shift, the Summit aims to expand national leaders’ horizons on how to create and capture new economic and social opportunities for the public.

To this end, the NBOS Summit created two platforms to support the transformation—the Pre-Summit and the Offsite. The process begins with the NBOS Summit, which sets the strategic priorities for pressing national issues that need to be resolved, and specifies in what sequence they will be addressed. The matters the members discuss range from safety and security issues, like rising crime and global terrorism; to economic issues, like urban and rural development, and the need for more innovation and entrepreneurship, stronger infrastructure, and youth employment; to social problems and issues of public well-being, such as women’s empowerment, inefficient government services, health care, low-cost housing, and environmental degradation, including wild animal poaching. Each Summit lasts three hours and ends with the announcement of new initiatives to pursue in addition to those already underway. The two supporting platforms then develop these initiatives in progressively greater detail.

With macro guidance from the NBOS Summit, the Pre-Summit, chaired by the chief secretary to the government, sets the scope, team members, and strategic direction for the new initiatives before handing them over to Offsite teams whom they’ve fully briefed. The Pre-Summit is composed of leaders chosen from government ministries, departments, and agencies who also prepare the Summit agendas and monitor the progress of ongoing initiatives to ensure their execution and resolve any cross-ministerial or cross-agency conflicts that occur during implementation.

Offsite platforms are made up of working-level teams tasked with executing the blue ocean initiatives. The leaders of these teams are also members of the Pre-Summit, thereby ensuring that their actions will be aligned. The teams develop detailed execution road maps, which lay out actionable tasks with clear time lines that each member can easily carry out and be held responsible for. Team members share their firsthand discoveries about on-the-ground realities in meetings, and they are empowered to adjust their execution road map accordingly, if necessary.

The chief secretary to the government and his team play a critical role across all three NBOS platforms by coordinating and orchestrating their efforts toward the country’s goals. From the beginning, this work of national transformation has consistently benefited from the leadership of competent, determined, and devoted chief secretaries whose contributions to shifting the nation from red to blue oceans cannot be overstated.

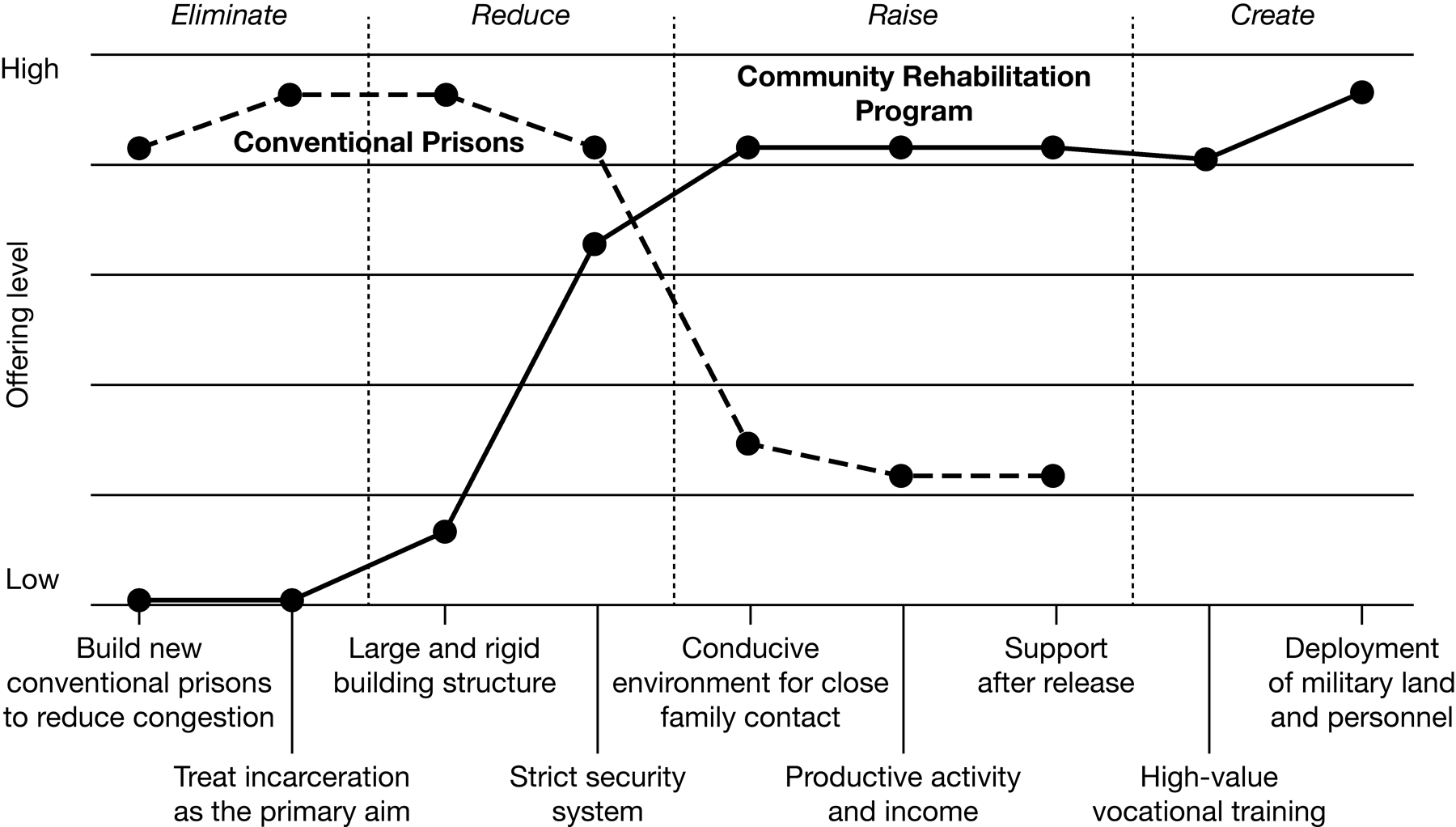

So that everyone could follow the strategy discussions and develop a shared understanding of the road ahead and what would need to be done, a common language across the three NBOS platforms was essential. Visual tools like the strategy canvas, the four actions framework, and the eliminate-reduce-raise-create (ERRC) grid served this purpose well. For example, by looking at a strategy canvas with a compelling tagline and the four actions drawn on a single page, as shown in figure E-1, people at every level of government and in all the relevant ministries and agencies could easily see and tell if a proposed move was indeed a shift and likely to open up a new value-cost frontier. Figure E-1 depicts the strategy canvas of the Community Rehabilitation Program (CRP), discussed in chapter 1, along with its tagline and four actions as presented at the Summit. As a quick reminder, the CRP was designed to rehabilitate petty criminals, who constitute the largest proportion of the country’s prisoners. Since the shift, the recidivism rate has plummeted, families are thrilled, and society is safer. As for cost, a CRP center is 85 percent cheaper to build than a conventional prison and 58 percent cheaper to run. Based on current numbers, CRP is projected to deliver over US$1 billion in reduced costs and social benefits in its first decade. Perhaps its greatest gift, however, is the way CRP enables former inmates to transform their lives by giving them hope, dignity, and the skills to become productive members of society.

Figure E-1

Strategy Canvas of Malaysia’s Community Rehabilitation Program

“Give a Second Chance Through Rehabilitation, Not Incarceration”

In formulating and executing initiatives, all NBOS platforms follow three overarching rules. One, to be considered, any idea or proposal must involve two or more ministries and be designed to meet the three blue ocean criteria of high impact, low cost, and rapid execution. Two, the principles of fair process—engagement, explanation, and clear expectations—need to be observed in all discussions and decision making. Three, market-creating tools like the strategy canvas, the four actions framework, and the ERRC grid are used, as applicable, and reflected in all discussions and reports. The Malaysia Blue Ocean Strategy Institute and the National Strategy Unit play important supporting roles throughout this process. The Summit takes the lead in driving the adoption of both the humanistic approach that earns people’s voluntary cooperation and the blue ocean tools that build their creative competence.

How the Journey Began

Malaysia’s blue ocean journey began humbly, in 2009, with a single initiative. Street crime was soaring. Snatch-theft was rampant, with thieves on motorcycles using rob-and-run tactics on pedestrians, mostly women. People wanted more police presence in the streets. While the police were doing their best to meet this demand, they lacked enough trained officers to staff more patrols. The police proposed building more training facilities to accelerate the number of recruits they could bring on. But with the world economy struggling to crawl out of the 2008 global financial crisis, and a rising government budget deficit, that option was off the table. The police were trapped in a red ocean of rising crime. Citizens were frustrated. And the competition—the criminal element—was winning out. The government recognized that conventional practices would not turn the situation around. A blue ocean shift was imperative.

As the Summit discussed the issue, it became clear that the Royal Malaysia Police couldn’t solve the problem alone. The Ministry of Home Affairs and the Department of Public Administration had to join in. The Summit empowered a cross-ministry team and asked them to present their strategic action plans at the next Summit. To this end, the team ran an initial round of Pre-Summit and Offsite meetings to deepen their understanding of the realities on the ground and create viable blue ocean alternative solutions.

The team found that a great many trained police officers across the nation were doing administrative tasks, such as writing up reports, managing inventory, and filing documents. Officers traditionally performed these tasks, so no one had ever questioned the practice. But why, the team wondered, couldn’t these activities be equally well performed by nonpolice personnel, freeing up the trained police officers for the patrols the citizens were crying out for? At the same time, by having members of the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Department of Public Administration on the team, the NBOS team found that the civil service had excess administrative staff on the payroll who had light workloads. A blue ocean opportunity existed to quickly move underleveraged, competent administrators locked in the “cold spots” of civil service departments to the “hot spots” at police stations. The team reckoned that such a move would allow the government to make an initial blue ocean shift, achieving high impact at low cost with rapid execution.

By then, the team was ready to chart specific strategies to execute the shift. But while the fair process practiced in all the platform meetings had aligned all the top-level people at the relevant governmental bodies, moving people across ministries and departments wasn’t simple. It would stir up deep turf wars, involve issues related to relocation and incentives, and require widespread changes in people’s mindsets and behaviors. Moreover, the Attorney General’s Chamber would need to check whether moving personnel across the legal boundary between the police and the civil service would violate any existing rules and regulations. And if it did, the chamber needed to figure out how to address the problem within the bounds of national law.

Having listened to all these findings and execution challenges, the Summit added the Attorney General’s Chamber to the team, approved the proposed approach, and asked the newly expanded team to map out and present an action plan with concrete milestones. At this point, the Pre-Summit and the NBOS Offsite platforms needed to be further mobilized to complete the task. The expanded team was also expected to show results within six months. A challenging time line like this would be used in all the subsequent NBOS projects, unless otherwise agreed to, as a way of creating a sense of urgency and inspiring innovative approaches to speed execution. Clear expectations and a sound explanation were provided up front to all NBOS members.

The team reported their progress to the Summit monthly for feedback. In a period of six months, over 7,400 trained police officers who had been doing desk work were released to do street patrols, while 4,000 civil servants were placed at the police stations to take over the officers’ administrative duties. Efficiency gains identified in the course of the shift process accounted for the reduction in personnel and further lowered costs. Compared with a convential red ocean approach, where new police officer candidates were recruited, trained, and sent out on patrols, this cross-agency and cross-departmental move saved the government hundreds of millions of US dollars and had a rapid impact on street security. From 2009 to the end of 2010, reported street crimes dropped by 35 percent, and they have continued to go down since then.

Even more rewarding were the changes in people’s attitudes and behaviors. New conversations, such as the following, began to take place: “I became a police officer the day I turned 22,” one officer said, turning to the civil servant who’d taken over his administrative work. “I spent 15 years on a beat and had finally gotten a nice job sitting in a comfortable air-conditioned office [remember, the weather in Malaysia is hot throughout the year]. But when you came, I had to go back out on street patrols in the hot sun, and I wasn’t happy about it.” The civil servant looked at the officer and replied, “Oh, that’s why you were so cold and confrontational when I started. But you’re different now. You’ve become cooperative and supportive. Why?” The officer smiled and answered, “I saw you excel at administrative tasks, which isn’t surprising, since it’s your thing. And I felt good about your work. More importantly, though, once I got back in a police car, I realized I’d missed the patrols and the fun of reconnecting with the people I protect and serve, and monitoring the comings and goings in neighborhoods. NBOS brought us together and made us work on things we like and are good at.” This exchange is not unique. While room for improvement still exists, and breaking down deeply divided silos will always take time and patience, it is not difficult to find positive exchanges like this across the country, as police officers and civil servants work together for the good of their country.

Similarly, some generals had initial reservations about the military’s involvement in the CRP initiative. They were concerned that it could distract them from their core duty of protecting the country from external threats or invasion. After several rounds of discussions, however, they all agreed to give the CRP initiative a try. As we’ve seen, it has been a great success. At a recent Summit, the chief of defense forces, the highest-ranking general in the military, reflected on their journey, “We have come a long way, and we now wholeheartedly embrace the change that NBOS represents. Our duty is to serve our country, and we have found new ways of doing so while maintaining our core focus on keeping the country safe.” Today, under NBOS, six CRP centers have been established and some 10,000 inmates rehabilitated.

Before NBOS the military and police almost never crossed the boundaries that separated their two institutions. That has changed. Multiple signs provide evidence that they now see protecting people and nation building as a common mission. For example, they have initiated joint patrols in crime hot spots, and the military has begun sharing their extra training facilities with the police. This has not only allowed the police to put trained officers on the streets more rapidly, but also resulted in significant cost savings by negating the need to build new police training facilities. “The police and military march at a different pace and salute in different ways,” the inspector general of police observed at one of the Summits. But, he suggested, together with the chief of defense forces, “to signify the change in the way we work together for the nation, why don’t we organize a joint graduation ceremony, so that the first batch of police recruits trained at military facilities will graduate side-by-side with military graduates? Such a ceremony would be a first in our history.” Over 20,000 people came to witness this historic event, and the spirit of change was high and palpable.

The Evolution of the Journey

Since 2009, the Malaysian government has initiated more than 100 blue ocean moves, involving over 90 ministries and agencies from finance, to education, to rural and regional development, to agriculture, to urban well-being, to defence, to housing and local government, to women, family, and community development. The issues they’ve addressed range from safety and security, to economic and social development, to the environment and public well-being. You can learn about these blue ocean moves at www.nbos.gov.my and www.blueoceanshift.com/malaysia-nbos. To date, the NBOS initiatives that have generated the widest demand among the citizenry are those focused on urban and rural well-being, entrepreneurship, and youth volunteerism. Let’s look briefly at an example of each.

In June 2012, NBOS established the first Urban Transformation Center (UTC) in Melaka City, one of the country’s state capitals. Since then, more than 20 others of varying size have been opened in main cities across the country. The UTCs are one-stop shops, where all government services are available under a single roof. Open seven days a week, from 8:30 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., they offer everything from passport renewals, licenses, legal permits, and registration forms to skill training programs, health clinics, social welfare programs, and official certificates of various kinds. The UTCs are soaringly popular—in a country with a population of slightly over 30 million, UTCs have counted nearly 50 million visits for government services in the first few years alone. In addition, people can also buy groceries, enjoy recreational facilities like fitness centers, and conduct their banking activities at the centers. Because UTCs are located in previously idling or underutilized government buildings, execution followed rapidly as soon as the Summit approved the idea. The first UTC building in Melaka was ready in just six weeks, and two weeks after that, the counters were open for business. Because ministries and agencies no longer need their own city offices, the UTCs will save the government billons of dollars in the years to come, while the gains in efficiency and convenience for the public, who no longer have to visit multiple offices, fighting city traffic all the while, are substantial. A similar model is at work in rural areas, where the NBOS Summit has established over 200 large and small Rural Transformation Centers (RTCs) to provide new economic, social, and educational opportunities that result in higher incomes for rural citizens.

The Malaysian Global Innovation and Creativity Center (MaGIC) is also a brainchild of the NBOS Summit. It brings together businesspeople, finance providers, domain experts, universities, and government officials to provide end-to-end support to both domestic and international entrepreneurs. Since its launch in April 2014, by then–US President Barack Obama and Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak, over 15,000 start-ups have been established with its support. MaGIC not only orchestrates the entrepreneurial ecosystem of the country but also builds its creative competence by teaching blue ocean tools and methods to people from all segments of the society. The MaGIC Accelerator program, which is building a community of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations)-focused start-ups, has become the largest in Southeast Asia.

The Summit’s decision to create 1Malaysia for Youth (iM4U) has had a similarly transformative effect on youth volunteerism. Launched in 2012, the initative was designed to open up a new frontier of volunteerism by building young people’s confidence and unlocking their energy and talent for the good of the nation. With about 3 million members, iM4U has become the largest youth volunteering organization in Southeast Asia and one of the biggest in the world. Its volunteers have carried out over 4,500 national and international projects to aid natural disaster relief efforts, provide supplementary schoolteachers, engage in charity work on behalf of the needy and elderly, perform local and regional community work, and more. This new and unprecedented level of youth volunteerism has impressed both the country’s citizens and the regional public. As for the youth, they have seen firsthand the positive impact they can have on the well-being of others, which increases their confidence, their pride in their accomplishments, and their skills—all at low cost to the government.

These initiatives are game changers, not only in the way people work together to create new value-cost frontiers but also in how they think about and carry out their roles and responsibilities. During one of the Summit meetings, the secretary general of treasury said with a big smile on his face, “I am a finance guy. Having been assigned to lead and execute initiatives like UTC and MaGIC, I learned a lot about how to think and act in a blue ocean way. My fellow NBOS team members and I have realized that we need to both ‘blue-ocean’ these initiatives, and shift our mindsets. For me, this means being more than a numbers-driven finance guy. To deliver our national budget with high impact at low cost with rapid execution, I need to be a blue ocean strategist.”

Since 2009, when the prime minister kicked off the National Transformation Journey where NBOS has played a pivotal role, the country’s gross national income has grown by nearly 50 percent, and over 2 million jobs have been created. The global community, especially the governments of emerging and developing nations, has taken notice, and asked the Malaysian government to share its experiences with them. Malaysia and its leadership responded positively, and the result was an international conference on NBOS, held on August 16–18, 2016.

The three-day conference took place in Putrajaya, the country’s federal administrative center outside downtown Kuala Lumpur, and attracted 5,500 attendees representing 45 countries. Among the participants were heads of state, ministers, civil service leaders, and representatives from the United Nations, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and member countries of the Commonwealth Association of Public Administration and Management.

The chief secretary to the government kicked off the conference by providing an overview of the NBOS initiatives. The prime minister then gave an inspiring keynote, explaining that “If we had continued with the old policies, we would have found the government and country swimming in an ocean of red. We knew that we had, instead, to make a paradigm shift, and create a new economic model; one driven by knowledge, creativity, and innovation—a ‘blue ocean’ of new opportunities.” In the panel of heads of state that followed, the prime minister of Thailand built on this idea, noting that “Especially in times of economic uncertainty, countries tend to return to competition-based red ocean strategy,” and urging the delegates to focus instead on “striving to innovate to create blue oceans.”

After these opening events, the conference broke into sessions where participants discussed not only how the initiatives had transformed the formulation and execution of national policies but also how such changes affected the mindsets and behaviors of the people involved, their ways of working together, and the economic and social landscape of the nation. The Malaysian defence minister, who when he was home affairs minister, led the very first NBOS initiative, shared his view that “NBOS continuously reminds us that things have got to be shaken up from time to time, and that we should always keep an open mind and cooperate with each other.” Given that the beginning of any change initiative is the most challenging period, his remarks, like his contributions, were especially resonant.

The conference also featured NBOS exhibitions, where participants could visit booths showcasing various initiatives and discuss what they’d heard. During the final day, they were also given the opportunity to visit one of the sites to experience firsthand how the initiative worked and how it affected people’s lives. The CRP Center at Gemas was one of the options; visitors were able to see the new, income-producing skills the inmates were learning, and to listen as they described their work and achievements with genuine pride.

“Transformation requires people to work together in new ways, to think differently, and to take on new roles and responsibilities. These are not easy things to do, but they are rewarding. Throughout our NBOS journey, we have been creating new ways to serve people better and deliver on the things that really matter to them. NBOS has been transforming the entire nation. Blue oceans ahead!” said Malaysia’s deputy prime minister in his concluding keynote address.

Today, at the Summit meetings, one can regularly hear participants talk about “blue-oceaning” initiatives and “NBOSing” their work. Presenting his vision for the nation at a recent Summit, the prime minister underscored the importance of this work, saying, “We aspire to be a top-20 nation in the world by 2050. For that, we need to persist on our blue ocean journey.” With recharged energy, the chief secretary to the government is vigorously orchestrating all NBOS activities, motivating the participants and monitoring and communicating the results. In a recent address to the civil service, he reflected, “No doubt, change is not easy. But miracles can happen, given a positive mindset, as we have seen through NBOS. NBOS is a pivotal pillar in our nation’s transformation journey.” So, with renewed confidence, the blue ocean shift continues.