Your view concerning Thoreau is entirely in consent with that which I entertain. His general conduct has been very satisfactory, and I was willing and desirous that whatever falling off there had been in his scholarship should be attributable to his sickness. He had, however, imbibed some notions concerning emulation and college rank which had a natural tendency to diminish his zeal, if not his exertions. His instructors were impressed with the conviction that he was indifferent, even to a degree that was faulty, and that they could not recommend him, consistent with the rule by which they are usually governed in relation to beneficiaries. I have always entertained a respect for and interest in him, and was willing to attribute any apparent neglect or indifference to his ill health rather than to wilfulness. I obtained from the instructors the authority to state all the facts to the Corporation, and submit the result to their discretion. This I did, and that body granted twenty-five dollars, which was within ten, or at most fifteen, dollars of any sum he would have received, had no objection been made. There is no doubt that, from some cause, an unfavorable opinion has been entertained, since his return after his sickness, of his disposition to exert himself. To what it has been owing may be doubtful. I appreciate very fully the goodness of his heart and the strictness of his moral principle; and have done as much for him as, under the circumstances, was possible.

—Emerson to Josiah Quincy, June 25, 1837109

At the “teacher’s meeting” last night, my good Edmund Hosmer, after disclaiming any wish to difference Jesus from a human mind, suddenly seemed to alter his tone, and said that Jesus made the world and was the Eternal God. Henry Thoreau merely remarked that “Mr. Hosmer had kicked the pail over.” I delight much in my young friend, who seems to have as free and erect a mind as any I have ever met. He told as we walked this afternoon a good story about a boy who went to school with him, Wentworth, who resisted the school mistress’s command that the children should bow to Dr. Heywood and other gentlemen as they went by, and when Dr. Heywood stood waiting and cleared his throat with a Hem, Wentworth said, “You need n’t hem, Doctor. I shan’t bow.”

—Journal, February 11, 1838110

My good Henry Thoreau made this else solitary afternoon sunny with his simplicity and clear perception. How comic is simplicity in this double-dealing, quacking world. Everything that boy says makes merry with society, though nothing can be graver than his meaning. I told him he should write out the history of his college life, as Carlyle has his tutoring. We agreed that the seeing the stars through a telescope would be worth all the astronomical lectures. Then he described Mr. Quimby’s electrical lecture here, and the experiment of the shock, and added that “college corporations are very blind to the fact that the twinge in the elbow is worth all the lecturing.”

—Journal, February 17, 1838111

Montaigne is spiced throughout with rebellion, as much as Alcott or my young Henry Thoreau.

—Journal, March 6, 1838112

Yesterday afternoon I went to the Cliff with Henry Thoreau. Warm, pleasant, misty weather, which the great mountain amphitheatre seemed to drink in with gladness. . . .

Have I said it before in these pages? then I will say it again, that it is a curious commentary on society that the expression of a devout sentiment by any young man who lives in society strikes me with surprise and has all the air and effect of genius.

—Journal, April 1838113

I cordially recommend Mr. Henry D. Thoreau, a graduate of Harvard University in August, 1837, to the confidence of such parents or guardians as may propose to employ him as an instructor. I have the highest confidence in Mr. Thoreau’s moral character, and in his intellectual ability. He is an excellent scholar, a man of energy and kindness, and I shall esteem the town fortunate that secures his services.

—Emerson’s recommendation for Thoreau, May 2, 1838114

Thoreau’s poetry; poetry pre-written; mass a compensation for quality.

—Notebook, 1838–44115

Henry Thoreau has just come, with whom I have promised to make a visit, a brave fine youth he is.

—Emerson to Mary Moody Emerson, September 1, 1838116

Henry Thoreau told a good story of Deacon Parkman, who lived in the house he now occupies, and kept a store close by. He hung out a salt fish for a sign, and it hung so long and grew so hard, black and deformed, that the deacon forgot what thing it was, and nobody in town knew, but being examined chemically it proved to be salt fish. But duly every morning the deacon hung it on its peg.

—Journal, September 8, 1838117

My brave Henry Thoreau walked with me to Walden this afternoon and complained of the proprietors who compelled him, to whom, as much as to any, the whole world belonged, to walk in a strip of road and crowded him out of all the rest of God’s earth. He must not get over the fence: but to the building of that fence he was no party. Suppose, he said, some great proprietor, before he was born, had bought up the whole globe. So he had been hustled out of nature. Not having been privy to any of these arrangements, he does not feel called on to consent to them, and so cuts fishpoles in the woods without asking who has a better title to the wood than he. I defended, of course, the good institution as a scheme, not good, but the best that could be hit on for making the woods and waters and fields available to wit and worth, and for restraining the bold, bad man. At all events, I begged him, having this maggot of Freedom and Humanity in his brain, to write it out into good poetry and so clear himself of it. He replied, that he feared that that was not the best way, that in doing justice to the thought, the man did not always do justice to himself, the poem ought to sing itself: if the man took too much pains with the expression, he was not any longer the Idea himself.

—Journal, November 10, 1838118

My Henry Thoreau has broke out into good poetry and better prose; he, my protester.

—Emerson to Margaret Fuller, February 7, 1839119

My brave Henry here who is content to live now, and feels no shame in not studying any profession, for he does not postpone his life, but lives already,—pours contempt on these crybabies of routine and Boston. He has not one chance but a hundred chances.

—Journal May 27, 1839120

Last night came to me a beautiful poem from Henry Thoreau, “Sympathy.” The purest strain, and the loftiest, I think, that has yet pealed from this unpoetic American forest. I hear his verses with as much triumph as I point to my Guido when they praise half-poets and half-painters.

—Journal, August 1, 1839121

I have a young poet in this village named Thoreau, who writes the truest verses.

—Emerson to Thomas Carlyle, August 8, 1839122

Now here are my wise young neighbors who, instead of getting, like the wordmen, into a railroad-car, where they have not even the activity of holding the reins, have got into a boat which they have built with their own hands, with sails which they have contrived to serve as a tent by night, and gone up the Merrimack to live by their wits on the fish of the stream and the berries of the wood.

—Journal, September 14, 1839123

My Henry Thoreau will be a great poet for such a company, and one of these days for all companies.

—Emerson to William Emerson, September 26, 1839124

I can read Plutarch, and Augustine, and Beaumont and Fletcher, and Landor’s Pericles, and with no very dissimilar feeling the verses of my young contemporaries Thoreau and Channing.

—Journal, October 1839125

Then we have Henry Thoreau here who writes genuine poetry that rarest product of New England wit.

—Emerson to Mary Moody Emerson, December 22, 1839126

I will show you Walden Pond, and our Concord poet too, Henry Thoreau.

—Emerson to Christopher Pearse Cranch, March 4, 1840127

Ah, Nature! the very look of the woods is heroical and stimulating. This afternoon in a very thick grove where Henry Thoreau showed me the bush of mountain laurel, the first I have seen in Concord, the stems of pine and hemlock and oak almost gleamed like steel upon the excited eye.

—Journal, November 20, 1839128

I like Henry Thoreau’s statement on Diet: “If a man does not believe that he can thrive on board nails, I will not talk with him.”

—Journal, June 18, 1840129

One reader and friend of yours dwells now in my house, and, as I hope, for a twelvemonth to come,—Henry Thoreau,—a poet whom you may one day be proud of;—a noble, manly youth, full of melodies and inventions. We work together day by day in my garden, and I grow well and strong.

—Emerson to Thomas Carlyle, May 30, 1841130

Our household is now enlarged by the presence of . . . Henry Thoreau who may stay with me a year. I do not remember if I have told you about him: but he is to have his board etc. for what labor he chooses to do: and he is thus far a great benefactor and physician to me for he is an indefatigable and a very skilful laborer and I work with him as I should not without him, and expect now to be suddenly well and strong though I have been a skeleton all the spring until I am ashamed. Thoreau is a scholar and a poet and as full of buds of promise as a young apple tree.

—Emerson to William Emerson, June 1, 1841131

I am sometimes discontented with my house because it lies on a dusty road, and with its sills and cellar almost in the water of the meadow. But when I creep out of it into the Night or the Morning and see what majestic and what tender beauties daily wrap me in their bosom, how near to me is every transcendent secret of Nature’s love and religion, I see how indifferent it is where I eat and sleep. This very street of hucksters and taverns the moon will transform to a Palmyra, for she is the apologist of all apologists, and will kiss the elm trees alone and hides every meanness in a silver-edged darkness. Then the good river-god has taken the form of my valiant Henry Thoreau here and introduced me to the riches of his shadowy, starlit, moonlit stream, a lovely new world lying as close and yet as unknown to this vulgar trite one of the streets and shops as death to life, or poetry to prose. Through one field only we went to the boat and then left all time, all science, all history, behind us, and entered into Nature with one stroke of a paddle. Take care, good friend! I said, as I looked west into the sunset overhead and underneath, and he with his face toward me rowed towards it,—take care; you know not what you do, dipping your wooden oar into this enchanted liquid, painted with all reds and purples and yellows, which glows under and behind you. Presently this glory faded, and the stars came and said, “Here we are”; began to cast such private and ineffable beams as to stop all conversation. A holiday villeggiatura, a royal revel, the proudest, most magnificent, most heart-rejoicing festival that valor and beauty, power and poetry ever decked and enjoyed—it is here, it is this.

—Journal, June 6, 1841132

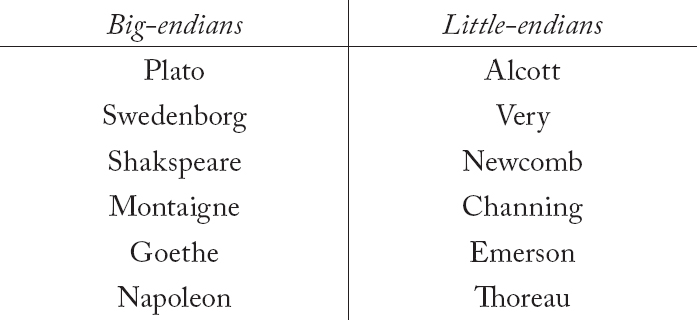

I told Henry Thoreau that his freedom is in the form, but he does not disclose new matter. I am very familiar with all his thoughts,—they are my own quite originally drest. But if the question be, what new ideas has he thrown into circulation, he has not yet told what that is which he was created to say. I said to him what I often feel, I only know three persons who seems to me fully to see this law of reciprocity or compensation,—himself, Alcott, and myself: and ’t is odd that we should all be neighbors, for in the wide land or the wide earth I do not know another who seems to have it as deeply and originally as these three Gothamites.

—Journal, September 1841133

Henry Thoreau is full of noble madness lately, and I hope more highly of him than ever. I know that nearly all the fine souls have a flaw which defeats every expectation they excite but I must trust these large frames as of less fragility—than the others. Besides to have awakened a great hope in another, is already some fruit is it not?

—Emerson to Margaret Fuller, September 13, 1841134

Henry is a person of extraordinary health and vigor, of unerring perception, and equal expression; and yet he is impracticable, and does not flow through his pen or (in any of our legitimate aqueducts) through his tongue.

—Journal, October 1841135

I am sorry that you, and the world after you, do not like my brave Henry any better. I do not like his piece very well, but I admire this perennial threatening attitude, just as we like to go under an overhanging precipice. It is wholly his natural relation and no assumption at all.

—Emerson to Margaret Fuller, July 19, 1842136

Henry Thoreau had been one of the family for the last year, and charmed Waldo by the variety of toys,—whistles, boats, popguns,—and all kinds of instruments which he could make and mend; and possessed his love and respect by the gentle firmness with which he always treated him. . . .

Henry Thoreau well said, in allusion to his large way of speech, that “his questions did not admit of an answer; they were the same which you would ask yourself.”

—Journal, January 30, 1842137

I have sometimes fancied my friend’s wisdom rather corrective than initiative, an excellent element in conversation to counteract the common exaggerations and preserve the sanity, but chiefly valuable so, and not for its adventure and exploration or for its satisfying peace.

—Journal, April 13, 1842138

Henry Thoreau made, last night, the fine remark that, as long as a man stands in his own way, everything seems to be in his way, governments, society, and even the sun and moon and stars, as astrology may testify.

—Journal, October–November 1842139

Last night Henry Thoreau read me verses which pleased, if not by beauty of particular lines, yet by the honest truth, and by the length of flight and strength of wing; for most of our poets are only writers of lines or of epigrams. These of Henry’s at least have rude strength, and we do not come to the bottom of the mine. Their fault is, that the gold does not yet flow pure, but is drossy and crude. The thyme and marjoram are not yet made into honey; the assimilation is imperfect.

—Journal, November 1842140

Elizabeth Hoar says, “I love Henry, but do not like him.” Young men, like Henry Thoreau, owe us a new world, and they have not acquitted the debt. For the most part, such die young, and so dodge the fulfilment. One of our girls said, that Henry never went through the kitchen without coloring.

—Journal, March–April 1843141

And now goes our brave youth into the new house, the new connexion, the new City. I am sure no truer and no purer person lives in wide New York; and he is a bold and a profound thinker though he may easily chance to pester you with some accidental crotchets and perhaps a village exaggeration of the value of facts.

—Emerson to William Emerson, May 6, 1843142

Henry Thoreau sends me a paper with the old fault of unlimited contradiction. The trick of his rhetoric is soon learned: it consists in substituting for the obvious word and thought its diametrical antagonist. He praises wild mountains and winter forests for their domestic air; snow and ice for their warmth; villagers and wood-choppers for their urbanity, and the wilderness for resembling Rome and Paris. With the constant inclination to dispraise cities and civilization, he yet can find no way to know woods and woodmen except by paralleling them with towns and townsmen. Channing declares the piece is excellent: but it makes me nervous and wretched to read it, with all its merits.

—Journal, August–September 1843143

Ellery Channing says, that writers never do anything: they are passive observers. Some of them seem to do, but they do not; Henry will never be a writer; he is as active as a shoemaker.

—Journal, 1843144

Precisely what the painter or the sculptor or the epic rhapsodist feels, I feel in the presence of this house, which stands to me for the human race, the desire, namely, to express myself fully, symmetrically, gigantically to them, not dwarfishly and fragmentarily. Henry David Thoreau, with whom I talked of this last night, does not or will not perceive how natural is this, and only hears the word Art in a sinister sense.

—Journal, February 1844145

Henry Thoreau said, he knew but one secret, which was to do one thing at a time, and though he has his evenings for study, if he was in the day inventing machines for sawing his plumbago, he invents wheels all the evening and night also; and if this week he has some good reading and thoughts before him, his brain runs on that all day, whilst pencils pass through his hands. I find in me an opposite facility or perversity, that I never seem well to do a particular work until another is due. I cannot write the poem, though you give me a week, but if I promise to read a lecture the day after to-morrow, at once the poem comes into my head and now the rhymes will flow. And let the proofs of the Dial be crowding on me from the printer, and I am full of faculty how to make the lecture.

—Journal, February 1844146

Henry Thoreau’s conversation consisted of a continual coining of the present moment into a sentence and offering it to me. I compared it to a boy, who, from the universal snow lying on the earth, gathers up a little in his hand, rolls it into a ball, and flings it at me.

—Journal, May 1844147

Henry said that the other world was all his art; that his pencils would draw no other; that his jackknife would cut nothing else. He does not use it as a means. Henry is a good substantial Childe, not encumbered with himself. He has not troublesome memory, no wake, but lives ex tempore, and brings to-day a new proposition as radical and revolutionary as that of yesterday, but different. The only man of leisure in the town. He is a good Abbot Samson: and carries counsel in his breast. If I cannot show his performance much more manifest that that of the other grand promisers, at least I can see that, with his practical faculty, he has declined all the kingdoms of this world. Satan has no bribe for him.

—Journal, May 1844148

Henry Thoreau said that the Fourierists had a sense of duty which led them to devote themselves to their second best.

—Journal, 1845149

Henry Thoreau complained that when he came out of the garden, he remembered his work.

—Journal, 1845150

A cat falls on its feet; shall not a man? You think he has character; have you kicked him? Talleyrand would not change countenance; Edward Taylor, Henry Thoreau, would put the assailant out of countenance.

—Journal, 1845151

Henry Thoreau says “that philosophers are broken-down poets”; and “that universal assertions should never allow any remarks of the individual to stand in their neighborhood, for the broadest philosophy is narrower than the worst poetry.”

—Journal, 1845152

Henry Thoreau objected to my “Shakespeare,” that the eulogy impoverished the race. Shakespeare ought to be praised, as the sun is, so that all shall be rejoiced.

—Journal, April 1846153

Queenie [Lidian Emerson] came it over Henry last night when he taxed the new astronomers with the poverty of their discoveries and showings—not strange enough. Queenie wished to see with eyes some of those strange things which the telescope reveals, the satellites of Saturn, etc. Henry said that stranger things might be seen with the naked eye. “Yes,” said Queenie “but I wish to see some of those things that are not quite so strange.”

—Journal, April 1846154

The teamster, the farmer, are jocund and hearty, and stand on their legs: but the women are demure and subdued as Shaker women, and, if you see them out of doors, look, as Henry Thoreau said, “as if they were going for the Doctor.”

—Journal, 1846155

Henry Thoreau seems to think that society suffers for want of war, or some good excitant. But how partial that is!

—Journal, June 1846156

Society is a curiosity-shop full of odd excellences, a Brahmin, a Fakeer, a giraffe, an alligator, Colonel Bowie, Alvah Crocker, Bronson Alcott, Henry Thoreau; a world that cannot keep step, admirable melodies, but no chorus, for there is no accord.

—Journal, June 1846157

In a short time, if Wiley & Putnam smile, you shall have Henry Thoreau’s “Excursion on Concord and Merrimack rivers,” a seven days’ voyage in as many chapters, pastoral as Isaak Walton, spicy as flagroot, broad and deep as Menu. He read me some of it under an oak on the river bank the other afternoon, and invigorated me.

—Emerson to Charles King Newcomb, July 16, 1846158

These—rabble—at Washington are really better than the sniveling opposition. They have a sort of genius of a bold and manly cast, though Satanic. They see, against the unanimous expression of the people, how much a little well-directed effrontery can achieve, how much crime the people will bear, and they proceed from step to step, and it seems they have calculated but too justly upon your Excellency, O Governor Briggs. Mr. Webster told them how much the war cost, that was his protest, but voted the war, and sends his son to it. They calculated rightly on Mr. Webster. My friend Mr. Thoreau has gone to jail rather than pay his tax. On him they could not calculate. The Abolitionists denounce the war and give much time to it, but they pay the tax.

—Journal, July 1846159

Henry Thoreau wants to go to Oregon, not to London. Yes, surely; but what seeks he but the most energetic Nature? And, seeking that, he will find Oregon indifferently in all places; for it snows and blows and melts and adheres and repels all the world over.

—Journal, 1847160

My friend Thoreau has written and printed in “Graham’s Magazine” here an Article on Carlyle which he will send to you as soon as the second part appears in a next number, and which you must not fail to read. You are yet to read a good American book made by this Thoreau, and which is shortly to be printed, he says.

—Emerson to Thomas Carlyle, February 27, 1847161

Henry Thoreau’s paper on Carlyle is printed in Graham’s Magazine: and his Book, “Excursion on Concord and Merrimack rivers” will soon be ready. Admirable, though Ellery Channing rejects it altogether. Mrs. Ripley and other members of the opposition came down the other night to hear Henry’s Account of his housekeeping at Walden Pond, which he read as a lecture, and were charmed with the witty wisdom which ran through it all.

—Emerson to Margaret Fuller, February 28, 1847162

Novels, Poetry, Mythology must be well allowed for an imaginative being. You do us great wrong, Henry Thoreau, in railing at the novel reading.

—Journal, May–June 1847163

Mr. Henry D. Thoreau of this town has just completed a book of extraordinary merit, which he wishes to publish. . . .

This book has many merits. It will be as attractive to lovers of nature, in every sense, that is, to naturalists, and to poets, as Isaak Walton. It will be attractive to scholars for its excellent literature, and to all thoughtful persons for its originality and profoundness. The narrative of the little voyage, though faithful, is a very slender thread for such big beads and ingots as are strung on it. It is really a book of the results of the studies of years.

—Emerson to Evert Duyckinck, March 12, 1847164

Thoreau sometimes appears only as a gendarme, good to knock down a cockney with, but without that power to cheer and establish which makes the value of a friend.

—Journal, July 10, 1847165

Henry Thoreau says that twelve pounds of Indian meal, which one can easily carry on his back, will be food for a fortnight. Of course, one need not be in want of a living wherever corn grows, and where it does not, rice is as good.

Henry, when you talked of art, blotted a paper with ink, then doubled it over, and safely defied the artist to surpass his effect.

—Journal, July 1847166

Henry D. Thoreau is a great man in Concord, a man of original genius and character, who knows Greek, and knows Indian also,—not the language quite as well as John Eliot—but the history monuments and genius of the Sachems, being a pretty good Sachem himself, master of all woodcraft, and an intimate associate of the birds, beasts, and fishes, of this region. I could tell you many a good story of his forest life.—He has written what he calls “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers,” which is an account of an excursion made by himself and his brother (in a boat which he built) some time ago, from Concord, Mass., down the Concord river and up the Merrimack, to Concord, N.H.—I think it a book of wonderful merit, which is to go far and last long. It will remind you of Izaak Walton, and, if it have not all his sweetness, it is rich, as he is not, in profound thought.

—Emerson to William H. Furness, August 6, 1847167

I have to thank you for your letter which was a true refreshment. Let who or what pass, there stands the dear Henry,—if indeed any body had a right to call him so,—erect, serene, & undeceivable. So let it ever be! I should quite subside into idolatry of some of my friends, if I were not every now and then apprised that the world is wiser than any one of its boys, and penetrates us with its sense, to the disparagement of the subtleties of private gentlemen.

—Emerson to Thoreau, January 28, 1848168

Charles Newcomb remarked, as Ellery Channing had done, the French trait in Henry Thoreau and in his family. Here is the precise voyageur of Canada sublimed, or carried up to the seventh power. In the family the brother and one sister preserved the French character of face.

—Journal, January–February 1848169

Henry Thoreau thought what we reckon a good Englishman is in this country a stage-proprietor.

—Journal, March 1848170

Henry Thoreau is like the wood-god who solicits the wandering poet and draws him into “antres vast and desarts idle,” and bereaves him of his memory, and leaves him naked, plaiting vines and with twigs in his hand. Very seductive are the first steps from the town to the woods, but the end is want and madness.

—Journal, August 1848171

I spoke of friendship, but my friends and I are fishes in our habit. As for taking Thoreau’s arm, I should as soon take the arm of an elm tree.

—Journal, August 1848172

Henry Thoreau, working with Alcott on the summer house, said, he was nowhere, doing nothing.

—Journal, Summer 1848173

We have not had since ten years a pamphlet which I have saved to bind! and here at last is Bushnell’s; and now, Henry Thoreau’s Ascent of Katahdin.

—Journal, October 1848174

Henry Thoreau sports the doctrines of activity: but I say, What do we? We want a sally into the regions of wisdom, and do we go out and lay stone wall or dig a well or turnips? No, we leave the children, sit down by a fire, compose our bodies to corpses, shut our hands, shut our eyes, that we may be entranced and see truly.

—Journal, October 1848175

My friends begin to value each other, now that Alcott is to go; and Ellery Channing declares, “that he never saw that man without being cheered,” and Henry says, “He is the best natured man I ever met. The rats and mice make their nests in him.”

—Journal, November 1848176

Henry Thoreau is still falling on some bold volunteer like his Dr. Heaton who discredits the regulars; but Thoreau like all the rest of sensible men, when he is sick, will go to Jackson and Warren.

—Journal, December 10, 1848177

Thoreau can pace 16 rods accurately.

—Journal, 1849178

—Journal, 1849179

It is well worth thinking on. Thus, if Thoreau, Ellery Channing, and I could (which is perhaps impossible) combine works heartily (being fired by such a desire to carry one point as to fuse all our repulsions and incompatibilities), I doubt not we could engender something far superior for quality and for effect to any of the thin, cold-blooded creatures we have hitherto flung into the light.

—Journal, February 1850180

In Natural History of Intellect Goethe becomes a sample of an eye, for he sees the site of Rome, its unfitness, he sees the difference between Palermo and Naples; he sees rivers, and which way they run. Henry Thoreau, too. An advancing eye, that like the heavens journeys too and sojourns not.

—Journal, 1850181

Nature, Ellery Channing thought, is less interesting. Yesterday Thoreau told me it was more so, and persons less. I think it must always combine with man. Life is ecstatical, and we radiate joy and honor and gloom on the days and landscapes we converse with.

—Journal, September 1, 1850182

Practical naturalist. Now that the civil engineer is fairly established, I think we must have one day a naturalist in each village as invariably as a lawyer or doctor. It will be a new subdivision of the medical profession. . . .

The universal impulse toward natural science in the last twenty years promises this practical issue. And how beautiful would be the profession. C.T. Jackson, John L. Russell, Henry Thoreau, George Bradford, and John Lesley would find their employment. All questions answered for stipulated fees; and, on the other hand, new information paid for, as a newspaper office pays for news.

—Journal, October 1850183

Rambling talk with Henry Thoreau last night, in accordance with my proposal to hold a session, the first for a long time, with malice prepense, and take the bull by the horns. We disposed pretty fast of America and England, I maintaining that our people did not get ripened, but, like the peaches and grapes of this season, wanted a fortnight’s more sun and remained green, whilst in England, because of the density, perhaps, of cultivated population, more caloric was generated and more completeness obtained. Layard is good example, both of the efficiency as measured by effect on the Arab, and in its reaction of his enterprise on him; for his enterprise proved a better university to him than Oxford or Sorbonne.

Henry thought “the English all train,” are mere soldiers, as it were, in the world. And that their business is winding up, whilst our pioneer is unwinding his lines.

I like the English better than our people, just as I like merchants better than scholars; for, though on a lower platform, yet there is no cant, there is great directness, comprehension, health, and success. So with English.

Then came the difference between American and English scholars. Henry said, the English were all bred in one way, to one thing; he had read many lives lately, and they were all one life, Southey, Campbell, Leigh Hunt, or whosoever; they went to Eton, they went to College, they went to London, they all knew each other, and never did not feel the ability of each. But here, Channing is obscure, Newcomb is obscure, and so all the scholars are in a more natural, healthful, and independent condition.

My own quarrel with America, of course, was that the geography is sublime, but the men are not. . . .

It was agreed, however, that what is called success in America or in England is none; that their book or man or law had no root in nature, of course!

—Journal, October 27, 1850184

Nothing so marks a man as bold imaginative expressions. Henry Thoreau promised to make as good sentences of that kind as anybody.

—Journal, 1850185

Is it not a convenience to have a person in town who knows where pennyroyal grows, or sassafras, or punk for a slow-match; or Celtis,—the false elm; or cats-o’-nine-tails; or wild cherries; or wild pears; where is the best apple tree, where is the Norway pine, where the beech, . . . where are trout, where woodcocks, where wild bees, where pigeons; or who can tell where the stake-driver (bittern) can be heard; who has seen and can show you the Wilson’s plover?

Thoreau wants a little ambition in his mixture. Fault of this, instead of being the head of American engineers, he is captain of a huckleberry party.

—Journal, July 1851186

Henry Thoreau will not stick, he is not practically renovator. He is a boy, and will be an old boy. Pounding beans is good to the end of pounding Empires, but not, if at the end of years, it is only beans.

I fancy it an inexcusable fault in him that he is insignificant here in the town. He speaks at Lyceum or other meeting but somebody else speaks and his speech falls dead and is forgotten. He rails at the town doings and ought to correct and inspire them.

—Journal, 1851187

It would be hard to recall the rambles of last night’s talk with Henry Thoreau. But we stated over again, to sadness almost, the eternal loneliness. I found that though the stuff of Tragedy and of Romances is in a moral union of two superior persons, and the confidence of each in the other, for long years, out of sight and in sight, and against all appearances, is at last justified by victorious proof of probity to gods and men, causing a gush of joyful emotion, tears, glory, or what-not,—though there be for heroes this moral union, yet they, too, are still as far off as ever from an intellectual union, and this moral union is for comparatively low and external purposes, like the coöperation of a ship’s crew or of a fire-club. But how insular and pathetically solitary are all the people we know!

—Journal, October 27, 1851188

“You may be sure Kossuth is an old woman, he speaks so well.” Said H.D.T.

—Journal, 1851189

Of Henry Thoreau. He who sees the horizon may securely say what he pleases of any tree or twig between him and it.

—Journal, 1852190

Observe, that the whole history of the intellect is expansions and concentrations. . . .

But all this old song I have trolled a hundred times already, in better ways, only, last night, Henry Thoreau insisted much on “expansions,” and it sounded new.

—Journal, May 1852191

I find in my platoon contrasted figures; as, my brothers, and Everett, and Caroline, and Margaret, and Elizabeth, and Jones Very, and Sam Ward, and Henry Thoreau, and Alcott, and Channing. Needs all these and many more to represent my relations.

—Journal, June 1, 1852192

Henry Thoreau’s idea of the men he meets is, that they are his old thoughts walking. It is all affectation to make much of them, as if he did not long since know them thoroughly.

—Journal, June 1, 1852193

Henry Thoreau rightly said, the other evening, talking of lightning-rods, that the only rod of safety was in the vertebræ of his own spine.

—Journal, July 1852194

Thoreau gives me, in flesh and blood and pertinacious Saxon belief, my own ethics. He is far more real, and daily practically obeying them, than I; and fortifies my memory at all times with an affirmative experience which refuses to be set aside.

—Journal, July 1852195

Lovejoy, the preacher, came to Concord, and hoped Henry Thoreau would go to hear him. “I have got a sermon on purpose for him.” “No,” the aunts said, “we are afraid not.” Then he wished to be introduced to him at the house. So he was confronted. Then he put his hand from behind on Henry, tapping his back, and said, “Here’s the chap who camped in the woods.” Henry looked round, and said, “And here’s the chap who camps in a pulpit.” Lovejoy looked disconcerted, and said no more.

—Journal, July 1852196

Henry Thoreau makes himself characteristically the admirer of the common weeds which have been hoed at by a million farmers all spring and summer and yet have prevailed, and just now come out triumphant over all lands, lanes, pastures, fields, and gardens, such is their pluck and vigor. We have insulted them with low names, too, pig-weed, smart-weed, red-root, lousewort, chickweed. He says that they have fine names,—amaranth, ambrosia.

—Journal, July 18, 1852197

Thoreau read me a letter from Harrison Gray Otis Blake to himself, yesterday, by which it appears that Blake writes to ask his husband for leave to marry a wife.

—Journal, October 1852198

Thoreau remarks that the cause of Freedom advances, for all the able debaters now are freesoilers, Sumner, Mann, Giddings, Hale, Seward, Burlingame.

—Journal, 1852199

Thoreau is at home; why, he has got to maximize the minimum; that will take him some days.

—Journal, December 1852200

At home, I found Henry himself, who complained of Clough or somebody that he or they recited to every one at table the paragraph just read by him and by them in the last newspaper and studiously avoided everything private. I should think he was complaining of one H.D.T.

—Journal, December 1852201

Henry is military. He seemed stubborn and implacable; always manly and wise, but rarely sweet. One would say that, as Webster could never speak without an antagonist, so Henry does not feel himself except in opposition. He wants a fallacy to expose, a blunder to pillory, requires a little sense of victory, a roll of the drums, to call his powers into full exercise.

—Journal, June 1853202

Henry Thoreau sturdily pushes his economy into houses and thinks it the false mark of the gentleman that he is to pay much for his food. He ought to pay little for his food. Ice,—he must have ice! And it is true, that, for each artificial want that can be invented and added to the ponderous expense, there is new clapping of hands of newspaper editors and the donkey public. To put one more rock to be lifted betwixt a man and his true ends. If Socrates were here, we could go and talk with him; but Longfellow, we cannot go and talk with; there is a palace, and servants, and a row of bottles of different coloured wines, and wine glasses, and fine coats.

—Journal, August 1853203

Sylvan [Henry Thoreau] could go wherever woods and waters were, and no man was asked for leave—once or twice the farmer withstood, but it was to no purpose,—he could as easily prevent the sparrows or tortoises. It was their land before it was his, and their title was precedent. Sylvan knew what was on their land, and they did not; and he sometimes brought them ostentatious gifts of flowers or fruits or shrubs which they would gladly have paid great prices for, and did not tell them that he took them from their own woods.

Moreover the very time at which he used their land and water (for his boat glided like a trout everywhere unseen,) was in hours when they were sound asleep. Long before they were awake he went up and down to survey like a sovereign his possessions, and he passed onward, and left them before the farmer came out of doors. Indeed, it was the common opinion of the boys that Mr. Thoreau made Concord.

—Journal, 1853204

Mother wit. Dr Johnson, Milton, Chaucer, and Burns had it. . . .

Henry Thoreau has it.

—Journal 1853205

Henry Thoreau says he values only the man who goes directly to his needs; who, wanting wood, goes to the woods and brings it home; or to the river, and collects the drift, and brings it in his boat to his door, and burns it: not him who keeps shop, that he may buy wood. One is pleasing to reason and imagination; the other not.

—Journal, September 1853206

My two plants, the deerberry vaccinium stamineum and the golden flowers Chrysopsis ——, were eagerly greeted here. Henry Thoreau could hardly suppress his indignation that I should bring him a berry he had not seen.

—Emerson to William Emerson, September 28, 1853207

The other day, Henry Thoreau was speaking to me about my lecture on the Anglo-American, and regretting that whatever was written for a lecture, or whatever succeeded with the audience was bad, etc. I said, I am ambitious to write something which all can read, like Robinson Crusoe. And when I have written a paper or a book, I see with regret that it is not solid, with a right materialistic treatment, which delights everybody. Henry objected, of course, and vaunted the better lectures which only reached a few persons. Well, yesterday, he came here, and at supper Edith, understanding that he was to lecture at the Lyceum, sharply asked him, “Whether his lecture would be a nice interesting story, such as she wanted to hear, or whether it was one of those old philosophical things that she did not care about?” Henry instantly turned to her, and bethought himself, and I saw was trying to believe that he had matter that might fit Edith and Edward, who were to sit up and go to the lecture, if it was a good one for them.

—Journal, December 1853208

Henry Thoreau charged Blake, if he could not do hard tasks, to take the soft ones, and when he liked anything, if it was only a picture or a tune, to stay by it, find out what he liked, and draw that sense or meaning out of it, and do that: harden it, somehow, and make it his own. Blake thought and thought on this, and wrote afterwards to Henry, that he had got his first glimpse of heaven. Henry was a good physician.

—Journal, March 1854209

Mr. Thoreau is a man of rare ability: he is a good scholar, and a good naturalist, and he is a man of genius, and writes always with force, and sometimes with wonderful depth and beauty.

—Emerson to Richard Bentley, March 20, 1854210

All American kind are delighted with “Walden” as far as they have dared say. The little pond sinks in these very days as tremulous at its human fame. I do not know if the book has come to you yet;—but it is cheerful, sparkling, readable, with all kinds of merits, and rising sometimes to very great heights. We account Henry the undoubted King of all American lions. He is walking up and down Concord, firm-looking, but in a tremble of great expectation.

—Emerson to George Bradford, August 28, 1854211

Thoreau thinks ’t is immoral to dig gold in California; immoral to leave creating value, and go to augmenting the representative of value, and so altering and diminishing real value, and, that, of course, the fraud will appear.

—Journal, 1857212

Henry Thoreau asks, fairly enough, when is it that the man is to begin to provide for himself?

—Journal, 1855213

It is true—is it not?—that the intellectual man is stronger than the robust animal man; for he husbands his strength, and endures. . . .

Henry Thoreau notices that Franklin and Richardson of Arctic expeditions outlived their robuster comrades by more intellect. Frémont did the same.

—Journal, 1855214

If I knew only Thoreau, I should think coöperation of good men impossible. Must we always talk for victory, and never once for truth, for comfort, and joy? Centrality he has, and penetration, strong understanding, and the higher gifts,—the insight of the real, or from the real, and the moral rectitude that belongs to it; but all this and all his resources of wit and invention are lost to me, in every experiment, year after year, that I make, to hold intercourse with his mind. Always some weary captious paradox to fight you with, and the time and temper wasted.

—Journal, February 1856215

It is curious that Thoreau goes to a house to say with little preface what he has just read or observed, delivers it in lump, is quite inattentive to any comment or thought which any of the company offer on the matter, nay, is merely interrupted by it, and when he has finished his report departs with precipitation.

—Journal, April 1856216

Yesterday to the Sawmill Brook with Henry. He was in search of yellow violet (pubescens) and menyanthes which he waded into the water for; and which he concluded, on examination, had been out five days. Having found his flowers, he drew out of his breast pocket his diary and read the names of all the plants that should bloom this day, May 20; whereof he keeps account as a banker when his notes fall due; Rubus triflora, Quercus, Vaccinium, etc. The Cypripedium not due till to-morrow. Then we diverged to the brook, where was Viburnum dentatum, Arrow-wood. But his attention was drawn to the redstart which flew about with its cheap, cheap chevet, and presently to two fine grosbeaks, rose-breasted, whose brilliant scarlet “bids the rash gazer wipe his eye,” and which he brought nearer with his spyglass, and whose fine, clear note he compares to that of a “tanager who has got rid of his hoarseness.” Then he heard a note which he calls that of the night-warbler, a bird he has never identified, has been in search of for twelve years, which, always, when he sees it, is in the act of diving down into a tree or bush, and which ’t is vain to seek; the only bird that sings indifferently by night and by day. I told him, he must beware of finding and booking him, lest life should have nothing more to show him. He said, “What you seek in vain for half your life, one day you come full upon—all the family at dinner. You seek him like a dream, and as soon as you find him, you become his prey.” He thinks he could tell by the flowers what day of the month it is, within two days. . . .

Water is the first gardener: he always plants grasses and flowers about his dwelling. There came Henry with music-book under his arm, to press flowers in; with telescope in his pocket, to see the birds, and microscope to count stamens; with a diary, jack-knife, and twine; in stout shoes, and strong grey trousers, ready to brave the shruboaks and smilax, and to climb the tree for a hawk’s nest. His strong legs, when he wades, were no insignificant part of his armour.

—Journal, May 21, 1856217

The finest day, the high noon of the year, went with Thoreau in a wagon to Perez Blood’s auction. . . .

Henry told his story of the Ephemera, the manna of the fishes, which falls like a snowstorm one day in the year, only on this river [the Assabet], not on the Concord, high up in the air as he can see, and blundering down to the river (the shad-fly), the true angler’s fly; the fish die of repletion when it comes, the kingfishers wait for their prey.

—Journal, June 2, 1856218

I go for those who have received a retaining fee to this party of Freedom, before they came into this world. I would trust Garrison, I would trust Henry Thoreau, that they would make no compromises.

—Journal, June 1856219

A walk around Conantum with Henry Thoreau. . . .

Henry expiated on the omniscience of the Indians.

—Journal, August 8, 1856220

If you talk with J.K. Mills, or J.M. Forbes, or any other State Street man, you find that you are talking with all State Street, and if you are impressionable to that force, why, they have great advantage, are very strong men. But if you talk with Thoreau or Newcomb, or Alcott, you talk with only one man; he brings only his own force.

—Journal, September 1856221

Thoreau says, that when he wakes in the morning, he finds a thought already in his mind, waiting for him. The ground is preoccupied.

—Notebook222

Walk yesterday, first day of May, with Henry Thoreau to Goose Pond, and to the “Red chokeberry Lane.” . . . From a white birch, Henry cut a strip of bark to show how a naturalist would make the best box to carry a plant or other specimen requiring care, and thought the woodman would make a better hat of birch-bark than of felt,—hat, with cockade of lichens thrown in. I told him the Birkebeiners of the Heimskringla had been before him.

We will make a book on walking, ’t is certain, and have easy lessons for beginners. “Walking in ten Lessons.”

—Journal, May 2, 1857223

Henry thinks that planting acres of barren land by running a furrow every four feet across the field, with a plough, and following it with a planter, supplied with pine seed, would be lucrative. He proposes to plant my Wyman lot so. Go in September, and gather white-pine cones with a hook at the end of a long pole, and let them dry and open in a chamber at home. Add acorns, and birch-seed, and pitch-pines. He thinks it would be profitable to buy cheap land, and plant it so.

—Journal, May 30, 1857224

Henry praises Bigelow’s description of plants: but knows sixty plants not recorded in his edition of Bigelow (1840).

—Journal, June 9, 1857225

On Sunday (June 6) on our walk along the river-bank, the air was full of the ephemerides, which Henry celebrates as the manna of the fishes.

—Journal, June 9, 1857226

On my return from England in 1848 he [Charles Bartlett] had bought some grass in my meadow of Henry D. Thoreau and had got it away contrary to agreement without paying. Henry Thoreau was vexed at this and I went to Mr. Hoar senior and asked him to collect the money which I think was $20. George Heywood was then in Mr. Hoar’s office, and did soon after collect it and pay me.

One day, I met Bartlett and told him we would, if he liked, go over the bounds, and mark them anew at our common expense. He agreed to it. I was going one day with Thoreau to the lot, for the purpose of marking the Lincoln line through my lot. We stopped at Bartlett’s house, and proposed to him to go now with us, and let Mr. Thoreau as surveyor, find or refind and mark anew the old bounds between us. He consented. Then Thoreau said, he would not go (if it were a joint expense) until Bartlett should pay his part, since Bartlett had cheated him in the matter of the grass. Bartlett then said, he would never pay for any work until it was done. So we left him at home, and Thoreau went with me and surveyed the Lincoln line through my lot.

—Journal, June 17, 1857227

Henry said of the railroad whistle, that Nature had made up her mind not to hear it, she knew better than to wake up: and, “The fact you tell is of no value, ’t is only the impression.”

—Journal, September 4, 1857228

Henry avoids commonplace, and talks birch bark to all comers, reduces them all to the same insignificance.

—Journal, Fall 1857229

Wonders of arnica. I must surely see the plant growing. Where’s Henry?

—Journal, Fall 1857230

Mr. Thoreau met your New Bedford Rev. Mr. Thomas, at my house, last evening. The naturalist was in the perfect spirits habitual to him, and the minister courteous as ever, and, as it happened, cognisant of the Cape, and of Henry’s travels thereon. I am bound to be specially sensible of Henry Thoreau’s merits, as he has just now by better surveying quite innocently made 60 rods of woodland for me, and left the adjacent lot, which he was measuring, larger than the deed gave it. There’s a surveyor for you!

—Emerson to Daniel Ricketson, January 10, 1858231

The question is,—Have you got the interesting facts? That yours have cost you time and labor, and that you are a person of wonderful parts, and of wonderful fame, in the society or town in which you live, is nothing to the purpose. Society is a respecter of persons, but Nature is not. ’T is fatal that I do not care a rush for all you have recorded, cannot read it, if I should try. Henry Thoreau says, “The Indians know better natural history than you, they with their type fish, and fingers the sons of hands.”

—Journal, January 1858232

I found Henry yesterday in my woods. He thought nothing to be hoped from you, if this bit of mould under your feet was not sweeter to you to eat than any other in this world, or in any world. We talked of the willows. He says, ’t is impossible to tell when they push the bud (which so marks the arrival of spring) out of its dark scales. It is done and doing all winter. It is begun in the previous autumn. It seems one steady push from autumn to spring.

I say, how divine these studies! Here there is no taint of mortality. How aristocratic, and of how defiant a beauty! This is the garden of Edelweissen.

—Journal, January, 1858233

Yesterday with Henry Thoreau at the Pond. . . .

I hear the account of a man who lives in the wilderness of Maine with respect, but with despair. It needs the doing hand to make the seeing eye, and my imbecile hands leave me always helpless and ignorant, after so many years in the country. The beauty of the spectacle I fully feel, but ’t is strange that, more than the miracle of the plant and animal, is the impression of mere mass of broken land and water, say a mountain, precipices, and waterfalls, or the ocean-side, and stars. These affect us more than anything except men and women. But neither is Henry’s hermit, forty-five miles from the nearest house, important, until we know what he is now, what he thinks of it on his return, and after a year. Perhaps he has found it foolish and wasteful to spend a tenth or twentieth of his active life with a muskrat and fried fishes. I tell him that a man was not made to live in a swamp, but a frog. If God meant him to live in a swamp, he would have made him a frog.

The charm which Henry uses for bird and frog and mink, is Patience. They will not come to him, or show him aught, until he becomes a log among the logs, sitting still for hours in the same place; then they come around him and to him, and show themselves at home.

—Journal, May 11, 1858234

John Brown shows us, said Henry Thoreau, another school to send our boys to,—that the best lesson of oratory is to speak the truth. A lesson rarely learned—to stand by the truth.

—Journal, Fall 1859235

I understand that there is some doubt about Mr. Douglass’s keeping his engagement for Tuesday next. If there is a vacancy, I think you cannot do a greater public good than to send for Mr. Thoreau, who has read last night here a discourse on the history and character of Captain John Brown, which ought to be heard or read by every man in the Republic.

—Emerson to Charles W. Slack, October 31, 1859236

Agassiz says, “There are no varieties in nature. All are species.” Thoreau says, “If Agassiz sees two thrushes so alike that they bother the ornithologist to discriminate them, he insists they are two species; but if he see Humboldt and Fred Cogswell, he insists they come from one ancestor.”

—Journal, April 1860237

Came out at Captain Barrett’s and through the fields again out at Flint’s.

A cornucopia of golden joys. Ellery Channing says that he and Henry Thoreau have agreed that the only reason of turning out of the mowing is not to hurt the feelings of the farmers; but it never does, if they are out of sight. For the farmers have no imagination. And it does n’t do a bit of hurt. Thoreau says that when he goes surveying, the farmer leads him straight through the grass.

—Journal, September 11, 1860238

Thoreau’s page remind me of Farley, who went early into the wilderness in Illinois, lived alone, and hewed down trees, and tilled the land, but retired again into newer country when the population came up with him. Yet, on being asked what he was doing, he pleased himself that he was preparing the land for civilization.

—Journal, January 1861239

Thoreau forgot himself once.

—Journal, January 1861240

All the music, Henry Thoreau says, is in the strain; the tune don’t signify, ’t is all one vibration of the string. He says, people sing a song, or play a tune, only for one strain that is in it. I don’t understand this, and remind him that collocation makes the force of a word, and that Wren’s rule, “Position essential to beauty,” is universally true, but accept what I know of the doctrine of leasts.

—Journal, 1861241

I often say to young writers and speakers that their best masters are their fault-finding brothers and sisters at home, who will not spare them, but be sure to pick and cavil, and tell the odious truth. It is smooth mediocrity, weary elegance, surface finish of our voluminous stock-writers, or respectable artists, which easy times and a dull public call out, without any salient genius, with an indigence of all grand design, of all direct power. A hundred statesmen, historians, painters, and small poets are thus made: but Burns, and Carlyle, and Bettine, and Michel Angelo, and Thoreau were pupils in a rougher school.

—Journal, February 1861242

Lately I find myself oft recurring to the experience of the partiality of each mind I know. I so readily imputed symmetry to my fine geniuses, or perceiving their excellence in some insight. How could I doubt that Thoreau, that Charles Newcomb, that Alcott, or that Henry James, as I successively met them, was the master-mind, which, in some act, he appeared. No, he was only master-mind in that particular act. He could repeat the like stroke a million times, but, in new conditions, he was inexpert, and in new company, he was dumb.

—Journal, October 1861243

As we live longer, it looks as if our company were picked out to die first, and we live on in a lessening minority. . . . I am ever threatened by the decay of Henry Thoreau.

—Journal, January 1862244

Thoreau. Perhaps his fancy for Walt Whitman grew out of his taste for wild nature, for an otter, a woodchuck, or a loon. He loved sufficiency, hate a sum that would not prove; loved Walt and hated Alcott.

—Journal, February 1862245

Alek Therien came to see Thoreau on business, but Thoreau at once perceived that he had been drinking, and advised him to go home and cut his throat, and that speedily. Therien did not well know what to make of it, but went away, and Thoreau said he learned that he had been repeating it about town, which he was glad to hear, and hoped that by this time he had begun to understand what it meant.

—Journal, February 1862246

Oliver Wendell Holmes came out late in life with a strong sustained growth for two or three years, like old pear trees which have done nothing for ten years, and at last begin and grow great. The Lowells came forward slowly, and Henry Thoreau remarks that men may have two growths like pears.

—Journal, March 1862247

The snow lies even with the tops of the walls across the Walden road, and, this afternoon, I waded through the woods to my grove. A chickadee came out to greet me. . . . Thoreau tells me that they are very sociable with wood-choppers, and will take crumbs from their hands.

—Journal, March 3, 1862248

Sam Staples yesterday had been to see Henry Thoreau. Never spent an hour with more satisfaction. Never saw a man dying with so much pleasure and peace. Thinks that very few men in Concord know Mr. Thoreau; finds him serene and happy.

Henry praised to me lately the manners of an old, established, calm, well-behaved river, as perfectly distinguished from those of a new river. A new river is a torrent; an old one slow and steadily supplied. What happens in any part of the old river relates to what befals in every other part of it. ’T is full of compensations, resources, and reserved funds.

—Journal, March 24, 1862249

Yesterday I walked across Walden Pond. To-day I walked across it again. I fancied it was late in the season to do thus; but Mr. Thoreau told me, this afternoon, that he has known the ice hold to the 18th of April.

—Journal, April 2, 1862250

Heard the purple finch this morning, for the first time this season. Henry Thoreau told me he found the Blue Snowbird (Fringilla hiemalis) on Monadnoc, where it breeds.

—Journal, April 16, 1862251

Henry Thoreau remains erect, calm, self-subsistent, before me, and I read him not only truly in his Journal, but he is not long out of mind when I walk, and, as to-day, row upon the pond. He chose wisely no doubt for himself to be the bachelor of thought and nature that he was,—how near to the old monks in their ascetic religion! He had no talent for wealth, and knew how to be poor without the least hint of squalor or inelegance. Perhaps he fell—all of us do—into his way of living, without forecasting it much, but approved and confirmed it with later wisdom.

—Journal, June 1862252

He loved the sweet fragrance of Melilot.

—Journal, June 1862253

He is very sensible of the odor of waterlilies.

—Journal, June 1862254

If there is a little strut in the style, it is only from a vigor in excess of the size of his body.

—Journal, June 1862255

I see many generals without a command, besides Henry.

—Journal, June 1862256

Henry Thoreau fell in Tuckerman’s Ravine, at Mount Washington, and sprained his foot. As he was in the act of getting up from his fall, he saw for the first time the leaves of the Arnica Mollis! the exact balm for his wound.

—Journal, June 1862257

By what direction did Henry entirely escape any influence of Swedenborg? I do not remember ever hearing him name Swedenborg.

—Journal, June 1862258

If we should ever print Henry’s journals, you may look for a plentiful crop of naturalists. Young men of sensibility must fall an easy prey to the charming of Pan’s pipe.

—Journal, June 1862259

I wish Thoreau had not died before you came. He was an interesting study. . . . Henry often reminded me of an animal in human form. He had the eye of a bird, the scent of a dog, the most acute, delicate intelligence—but no soul. No . . . Henry could not have had a human soul.

—Emerson to Rebecca Harding Davis260

I have never recorded a fact, which perhaps ought to have gone into my sketch of “Thoreau,” that, on the 1st August, 1844, when I read my Discourse on Emancipation [in the British West Indies], in the Town Hall, in Concord, and the selectmen would not direct the sexton to ring the meeting-house bell, Henry went himself, and rung the bell at the appointed hour.

—Journal, April–May 1863261

In reading Henry Thoreau’s Journal, I am very sensible of the vigor of his constitution. That oaken strength which I noted whenever he walked, or worked, or surveyed wood-lots, the same unhesitating hand with which a field-laborer accosts a piece of work, which I should shun as a waste of strength, Henry shows in his literary task. He has muscle, and ventures on and performs feats which I am forced to decline. In reading him, I find the same thought, the same spirit that is in me, but he takes a step beyond, and illustrates by excellent images that which I should have conveyed in a sleepy generality. ’T is as if I went into a gymnasium, and saw youths leap, climb, and swing with a force unapproachable,—though their feats are only continuations of my initial grapplings and jumps.

—Journal, June 1863262

See in politics the importance of minorities of one. . . . Silent minorities of one also, Thoreau, Very, Newcomb, Alcott. . . . Christianity existed in one child.

—Journal, July 1863263

State your opinion affirmatively and without apology. Why need you, who are not a gossip, talk as a gossip, and tell eagerly what the Journals, or Mr. Sumner, or Mr. Stanton, say? The attitude is the main thing. John Bradshaw was all his life a consul sitting in judgment on kings. Carlyle has, best of all men in England, kept the manly attitude in his time. His errors of opinion are as nothing in comparison with this merit, in my opinion. And, if I look for a counterpart in my neighbourhood, Thoreau and Alcott are the best, and in majesty Alcott exceeds. This aplomb cannot be mimicked. It is the speaking to the heart of the thing.

—Journal, October 1863264

Thoreau thought none of his acquaintances dare walk with a patch on the knee of his trousers to the Concord Post-Office.

—Journal, 1863265

And I remember that Thoreau, with his robust will, yet found certain trifles disturbing the delicacy of that health which composition exacted,—namely, the slightest irregularity, even to the drinking too much water on the preceding day.

—“Inspiration”266

I see the Thoreau poison working today in many valuable lives, in some for good, in some for harm.

—Journal, 1864267

Among “Resources,” too, might be set down that rule of my travelling friend, “When I estimated the costs of my tour in Europe, I added a couple of hundreds to the amount, to be cheated of, and gave myself no more uneasiness when I was overcharged here or there.”

So Thoreau’s practice to put a hundred seeds into every melon hill, instead of eight or ten.

—Journal, September 1864268

Thoreau was with difficulty sweet.

—Journal, September 1864269

I am sure he is entitled to stand quite alone on his proper merits. There might easily have been a little influence from his neighbors on his first writings: He was not quite out of college, I believe, when I first saw him: but it is long since I, and I think all who knew him, felt that he was the most independent of men in thought and in action.

—Emerson to James Bradley Thayer, August 25, 1865270

When Henry Thoreau in his tramp with his companion came to a field of good grass, and his companion hesitated about crossing it, Henry said, “You may cross it, if the farmer is not in sight: it does not hurt the grass, but only the farmer’s feelings.”

—Journal, 1868271

How dangerous is criticism. My brilliant friend cannot see any healthy power in Thoreau’s thoughts. At first I suspect, of course, that he oversees me, who admire Thoreau’s power. But when I meet again fine perceptions in Thoreau’s papers, I see that there is defect in his critic that he should undervalue them. Thoreau writes, in his Field Notes, “I look back for the era of this creation not into the night, but to a dawn for which no man ever rose early enough.” A fine example of his affirmative genius.

—Journal, February 1870272

Henry Thoreau was well aware of his stubborn contradictory attitude into which almost any conversation threw him, and said in the woods, “When I die, you will find swamp oak written on my heart.” I got his words from Ellery Channing today.

—Journal, April–June 1870273

Plutarch loves apples like our Thoreau, and well praises them.

—Journal, 1870274

I delight ever in having to do with the drastic class, the men who can do things. . . . Such was Thoreau.

—Journal, November 30, 1870275

I think highly of Thoreau. He is now read by a limited number of men and women, but by very ardent ones. They were dissatisfied with my notice of him in the Atlantic after his death: they did not want me to place any bounds to his genius. He came to me a young man, but was so popular with young people that he quite superseded his old master. But now and then I come across a man that scoffs at Thoreau and thinks he is affected. For example, Mr. James Russell Lowell is constantly making flings at him. I have tried to show him that Thoreau did things that no one could have done without high powers; but to no purpose. I am surprised to hear that you have read Thoreau. Neither his books nor mine are much read in the South, I suppose. . . .

Thoreau was unacquainted with the technical names of plants when I first knew him. On my telling him the name of a flower, he remarked that he should never see the flower again, for if he met it he would be able only to see the name. He, however, afterward became quite accurate in botany. His cabin, or hut, stood on this very spot. There is a pious mark (a cross) on that tree which indicates the place. I don’t know who made the mark: I did not. Daily before taking his walk he would examine his diary to see what flowers should be out. His hut was in full view of Walden Pond: these trees here have grown up since then. He could run out on awaking and leap right into the water, which he did every morning.

—Emerson to Pendleton King, June 1870276

How vain to praise our literature, when its really superior minds are quite omitted, and utterly unknown to the public. . . . Thoreau quite unappreciated, though his books have been opened and superficially read.

—Journal, October–November 1871277

Henry Thoreau we all remember as a man of genius, and of marked character, known to our farmers as the most skilfull of surveyors, and indeed better acquainted with their forests and meadows and trees than themselves, but more widely known as the writer of some of the best books which have been written in this country, and which, I am persuaded, have not yet gathered half their fame. He, too, was an excellent reader. No man would have rejoiced more than he in the event of this day.

—“Address at the Opening of the Concord Free Public Library”278

There was something fine in Thoreau. I have tried to convince Lowell, Longfellow, and Judge Hoar of this. . . . He has left behind him much manuscript on natural history, beautiful and as fine as Linnæus; but I get no encouragement from the publishers to bring it out. From Thoreau might be collected a book of proverbs or sentences that would charm the Hindoos. . . .

Thoreau once took charge of my garden, and on the occasion of a visit from Theodore Parker I sent Thoreau to the station for him, hoping that he would like Parker; but he did not, and expressed a contempt for the man. Haughtiness of manner was frequently a characteristic of Thoreau.

—Emerson to Pendleton King, Spring 1875279

I can well understand that he should vex tender persons by his conversation, but his books, I confide, must and will find a multitude of readers.

—Emerson to Harrison Gray Otis Blake, December 7, 1876280

I have to thank you for the very friendly notice of myself which I find in your monthly magazine, which I ought to have acknowledged some days ago. The tone of it is courtly and kind, and suggests that the writer is no stranger to Boston and its scholars. In one or two hints, he seems to me to have been misinformed. The only pain he gives me is in his estimate of Thoreau, whom he underrates. Thoreau was a superior genius. I read his books and manuscripts always with new surprise at the range of his topics and the novelty and depth of his thought. A man of large reading, of quick perception, of great practical courage and ability,—who grew greater every day, and, had his short life been prolonged, would have found few equals to the power and wealth of his mind.

—Emerson to George Stewart, Jr., January 22, 1877281