VII

HYLAS Philonous, I think I have discovered the fundamental difference between an electronic brain and an organism. When an electronic network solves a problem, it can immediately forget it. In this way calculators are totally unaware of the mathematical operations they have just done. But a living brain never forgets its past, or at least an outline of it. So for a neuronal network the whole life of the organism from beginning to end is like a single task; the network builds its personality, character, and individuality in the course of solving it. Therefore, such a network cannot start “truly anew,” make itself empty and blank again as an electronic network can. Right?

PHILONOUS This is true for currently existing electronic brains but will not be true for those constructed in the future. I have already mentioned that network engineers are not interested in imitating the total of a brain’s activities; they only want to make devices that can mimic a specific, narrow subset of the nervous system’s functions. They always intended to build not an “autonomous” network “that can form a personality” but only steering and controlling systems for industry, machines that can reason logically or shoot down an airplane, and the analogies with the functions of the nervous systems that emerged in those devices, surprised them too. Only recently they turned to machines that can imitate the behavior of living organisms, that is, machines that can learn based on conditioned reflexes and manifest elementary tropisms, for example.

The irreversibility of processes in a neuronal network is closely related to its complexity and to some extent its building material, as physicochemical changes occurring in it (for example in the course of development or aging) substantially affect its function. It is especially interesting to note that the human brain’s network forms during development, and not only functionally. Large parts of an infant’s brain are almost totally inactive; they gradually “plug into” the functioning network between the second and seventh, or even tenth, year of life. This process manifests anatomically as the myelinization of the nerve fibers in various parts of the brain, mainly in the frontal lobes, which, being the site of higher-level mental processes, become functional latest. This is no doubt related to some features of neuronal network’s functioning, one of which is the subjective perception of the passage of time: an hour is considerably longer for a child than for an adult. This difference is not an illusion but a result of an increasing differentiation and complication of the network, along with the processes in it, with age. The irreversibility of the processes in a neuronal network thus has numerous causes because such a network develops both functionally and structurally, whereby it increases its informational capacity. Of course, we could create an electronic network that “develops” in the same way. Initially it would have a relatively simple “active nucleus,” but in the passage of time and as new needs appear, various supporting subsystems would attach, obviously in a way that allows no conflict between the original nucleus and the subsystems. But let us now leave this aspect and turn to our main topic, which is the application of cybernetics to studies of the structure and function of society. Society, as a system (organized set) of elements interconnected by feedback, is, paradoxically, more like an electronic brain than like a living organism.

HYLAS I fail to see this similarity.

PHILONOUS An electronic brain can approach a new task with no memory of what it did before. A neuronal network cannot regroup its internal elements in a way that would return it to its original position as society can. An organism and a society share some features—in both there is circulation of information, matter, and energy, and both are subject to the fundamental laws of cybernetics (e.g., regarding the measurability of information, feedback, and preference systems)—but there is a principial difference between them: society, because of the looser connection among its elements, possesses a degree of “internal recombination freedom” that no living being does. That is why society is not an analogue of an organism, and it is a mistake to draw any sociobiological parallels between the two.

HYLAS But an electronic brain, you say . . . ?

PHILONOUS Well, I may have slightly exaggerated the similarity between an electronic brain and a social structure, because society differs, and quite significantly, from the existing electronic brains. The possibility of constructing an electronic network that would be a functionally equivalent model of a society does exist, at least in theory. But we are closer to constructing a network equivalent to the human brain.

HYLAS Why? Society must be structurally less complex than a neuronal network consisting of 10 billion elements.

PHILONOUS Except that every element of a society (i.e., a person) is itself a neuronal network, hence a society possesses a vast range of possible responses, its complexity equals to the “personal” one raised to an exponent that is the number of members of the society.

HYLAS Now the problem seems hopeless. What is the solution? Are you saying that in order to study societal processes we would have to build an electronic model of monstrous size?

PHILONOUS No monster brain would be needed. A phenomenon known from physics and biology comes to our rescue: the laws of statistics.

HYLAS I hate hearing about the use of mathematics right at the beginning. It takes us into a thicket of abstractions, in which we get completely lost.

PHILONOUS The mathematics necessary for the creation of a theory of social processes is indeed thorny, but we will not go deep into it, especially because this field is still incomplete and imperfect. And for the same reason we cannot succeed in forming a unified theoretical model of human social activity. At best we will only shed a little light on certain aspects of this immense task. Let us start with the basics.

The feedback links that an organism possesses are principially negative only: they always act to reduce the influence of whatever diverts the network from its goal. An antiaircraft gun reduces its aiming error in each consecutive shot. An automatic pilot reduces the airplane’s deviation from the set course. Negative feedback in a network subject to diverting forces is therefore characterized by a series of diminishing oscillations (error to one side—correction—error to the other side—correction—hit). But there is also positive feedback, which amplifies instead of reducing a stimulus. Some devices in radio engineering, such as so-called reactive amplifiers, are built on this principle. In an organism, however, positive feedback appears only in pathological states, because it works to the detriment of the network (and the organism).

HYLAS I recall something you said about an increase in electric potential in the cerebral cortex in response to light at certain frequencies, which can lead to an oscillation that causes an epileptic attack. Is this an example of harmful positive feedback in the cortex?

PHILONOUS Unfortunately, it is not so simple. It is not clear if that feedback is positive or negative.

HYLAS How come?

PHILONOUS The feedback does not respond to the stimulus immediately but always with a delay. Time is required for the impulse to enter the network, for a circuit to close, and for the correcting impulse (response) to be emitted. An autopilot in an airplane responds to a wind-caused deviation from the set course by forcing a deviation to the opposite side, but always with a delay. The two deviations (one caused by the wind, one caused by the autopilot) overlay and cancel each other so that the airplane stays on course. Except that in reality there are small deviations from a straight line: first a deflection caused by the wind and then another, to the opposite direction, due to the pilot’s reaction. If, however, the wind does not blow continuously but comes in gusts at intervals equal to the delay in the pilot’s response, the deviations to the left and right repeat in a way that causes the system to oscillate. This tendency to oscillate is the Achilles’ heel of all self-regulating systems with negative feedback. In general, when a stimulus is not constant but acts with a specific period and this period approaches the characteristic delay of the system, the system begins to oscillate. Because feedback, attempting to compensate for a stimulus-caused deviation, provides the corrective deviation with a delay, the result, in the case of a periodic stimulus, is just the opposite of what was intended: instead of decreasing, the oscillation amplifies to the point of exceeding the limit of the system’s mechanical stability. Every feedback system falls into oscillations when the delay of its reaction equals to one half of the period of the external stimulus.

HYLAS I’m not sure I follow.

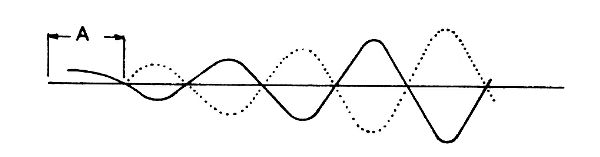

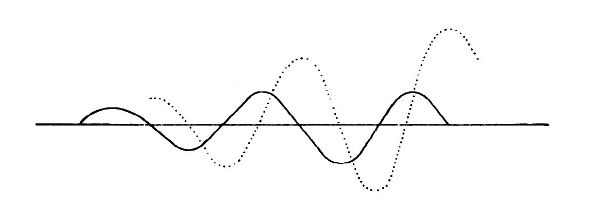

PHILONOUS Imagine that our airplane is pushed off course by gusts of wind with the same period as the delay of the pilot’s response. The result will be a series of repeating deviations in opposite directions such that the flight path becomes a sinusoid. Different systems have different delays. In electronic networks, they are thousandths of a second; in neuronal networks, tenths of a second. The mechanism of the whole phenomenon can be shown in this figure:1

- delay of reaction to the stimulus = A

- stimulus ______________

- reaction ---------------------

If the correction is greater than the stimulus-induced deviation, an increase in oscillation results. When the correction and deviation are equal, we get an oscillation with a constant amplitude. In the case of positive feedback instead, the relation between stimulus and response differs in that the correction is to the same side as the deviation:

- stimulus ______________

- reaction ---------------------

Thus, even though negative and positive feedback enact correction with the opposite and the same sign as the deviation, respectively, both cases may lead to sustaining or even increasing the oscillation instead of dampening it. Yet it is worth noting that negative feedback quenches all stimuli except those that act with a period equal to the system’s reaction delay (or its multiple), whereas positive feedback never quenches any oscillation.

HYLAS I see, sort of, but don’t know why you are talking at such length about induced oscillations in feedback systems.

PHILONOUS Because such oscillations lie at the heart of many important social phenomena. For example, in a capitalist economy, the alternating periods of boom and bust.

HYLAS What type of feedback is in operation there, negative or positive?

PHILONOUS Both. Suppose a producer supplies a product that brings profit. To increase the profit, the producer supplies more of the product. The market absorbs it. You have positive feedback between supply and demand, hence an increase in production. But the reaction delay, that is, the delay in providing more of the product, begins to affect the market. When supply exceeds demand, you have overproduction. The market does not absorb the product, the producer profits less, and therefore produces less and lays off workers. After the boom, the bust begins. A steep enough depression causes a crisis. A crisis occurs when the existing social structure fails as a result of a sharp increase in economic oscillation. If, in the worst of the depression, the social structure changes (e.g., through a revolution), the structural factors that induced the oscillation disappear. If there is no change, the system returns to relative equilibrium after a while, and the whole game starts over. But besides positive feedback, negative (corrective) feedback also operates in society, in the form of human intervention aimed at stopping or at least decreasing the oscillation through appropriate regulatory action. We will get to that later. Let us now take a look at the general characteristics of a social system.

First, the delays in the functioning of feedback are much longer in society than in a neuronal or electronic network: they could be on the order of many months or even years compared to milliseconds. Second, and this is essential, the operational rules of a social system are nonlinear. A system is linear if changes within it are proportional to their causes (the responses to the stimuli). The rules describing such a system have the form of differential equations and can be mathematically described with high precision. In contrast, methods for studying nonlinear systems are much more complex and do not provide entirely certain results.

HYLAS Why is that?

PHILONOUS Trying not to get too much off course, let us limit ourselves to defining the main difference between the two types of systems. A society or a neuronal network of the brain is a nonlinear system; a group of atoms or stars is a linear system. Linear systems have laws that are constant, so when we discover them, we can predict future states of a system based on knowing its present one. The laws of celestial mechanics enable us to predict with great accuracy the positions of planets and stars in a hundred thousand or million years. Nonlinear systems also possess laws, but they are not permanent and change over time. In the social system, people do not necessarily behave the same way when put twice in the same situation because of their changing mental state, which makes the latter an essential process parameter. Being aware of the consequences of an atomic weapon, for example, may explain why, in a situation no different from one that in the past always led to war, people refrain from engaging in an armed conflict today.

HYLAS But people did not have atomic weapons in the past, which hardly makes this a valid analogy.

PHILONOUS You are right; it was not the best example. Let us put the idea this way: if a nation manifested great bravery but little restraint many times in the past and the result was tremendous loss of life, in a situation that previously provoked violent action, it might now show restraint.

If the universe were a nonlinear system, it would not have constants like the speed of light,2 the Planck constant, the atomic constants, and so on. Yet the universe may actually be a nonlinear system, and all the values that we consider constant are subject to change, although we are unable to observe that because it takes place in intervals spanning hundreds of billions or trillions of years. Which would also explain why all our cosmological hypotheses of what the universe was like in a remote past or what it will be like in a distant future have so little credibility and certainty. In the realm of physical laws we can dismiss what is just probable and irrelevant for predictions spanning thousands or millions of years. (A diagram of a nonlinear trajectory will be a curve. Very short segments of a curve can be treated, with an approximation justified by practice, as a straight line, which means that within a limited time interval a system can be considered linear and its laws constant.) However, in the realm of social systems and their laws, which are nonlinear, we cannot dismiss that.

One of the largest and oldest nonlinear systems that we can examine is the entire evolution of life on our planet. I already spoke of the cyclical links among its elements and of the feedback relations that operate in a single evolving species. But I have not mentioned the feedback between different species of animals and plants. Such phenomena are studied by population dynamics. Take two animal species, one a carnivorous predator feeding on the other, herbivorous. There is periodic oscillation in the number of individuals in both species, because the predators reproduce faster only when they find enough prey. When the carnivores become so numerous that they eat more herbivores than are born, the number of carnivores decreases because of the scarcity of food. After some time (the feedback reaction delay), this decrease causes an increase in the number of the herbivores which are now less hunted, and the cycle starts again. Here we have a linear relation, since in a time interval of, say, a few hundred years, deviations from the direct proportionality that result from the evolution of forms (i.e., the phylogenetic changes that affect population dynamics) can be safely ignored. This is why the differential equations of Volterra, who studied these phenomena, describe the dynamics of such a population so well.3 Yet in reality the matter is much more complicated, because feedback does not connect only two species but includes all the animals and plants living in that particular environment. This feedback, moreover, is responsible for phenomena on a global scale. For example, consider that the total mass of living organisms on our planet more or less equals the total mass of free oxygen in the atmosphere.

For us, it is significant that in the course of evolution a dynamic equilibrium was reached among all existing species through this feedback such that the population did not fluctuate far from the average. Only human intervention can drastically disturb this equilibrium. For example, an unexpected but experimentally confirmed result of Volterra’s equations is that protecting the herbivore species also increases the number of individuals in the carnivore species. Similarly, the application of an insecticide against plant pests can, via feedback, affect the existing biological equilibrium so that severe disturbances of population dynamics arise, which may even lead to the extinction of a species that the insecticide does not harm at all. Ignorance of specific feedback connections may therefore pervert the human intention in nature and also, as we shall see in a moment, in social systems.

Oscillations in social systems are fundamentally different from those in biological populations. First, feedback connections in biological populations are relatively constant, given the very slow rate of change in the environment and the organisms themselves (in the speed of signal transmission in their neuronal networks, response types, lifespan, type of food, etc.). In particular, the delay in response remains the same over millions of years. The operation of feedback in society, on the other hand, has accelerated during human development, because of organizational efforts (labor) and the consequent changes in the methods of production and communication. Second, animals are subject to the dynamic laws of the system to which they belong but they cannot knowingly influence those laws. In society, human beings can. The difference is like that between the way animals and people “arm” themselves—the former by developing tusks and horns and the latter through engineering.

HYLAS Where are you headed with all these evolutionary divagations?

PHILONOUS To point out that a biological species evolves not only because of the selection pressures of climate and geology but also, and often predominantly, because of feedback of the kind that Volterra described. A newly appearing species may disturb the biological equilibrium of others and change the feedback loops in such a way that that it causes extinction of a species that it does not directly predate. Precisely this type of phenomenon was responsible, according to current views, for the mass extinction of the giant Mesozoic saurians.4

A biological population that is internally unstable, with increasing oscillations in one parameter and decreasing oscillations in another (because feedback does more than just regulate the number of individuals!), evolves spontaneously through interspecies feedback, whereas an internally unstable and oscillating social system may neither break down nor evolve structurally into another, new system. I am not comparing the two whole sets of the dynamic laws—of biological populations and social systems—but simply highlighting this essential difference between them.

When we do compare the dynamic laws of a biological population and of a social system, we find that the former can exist for a long time in a stable form only if it achieved equilibrium and is internally stable. In contrast, the latter can exist for a long time even when it is unstable—for the reason that a social system can be “forced” into stability using coercion (force). This is why changes in social systems throughout history tend to have a violent character, unlike in biological evolution, whose course never changes abruptly.

Social systems exhibit oscillations in a number of parameters but economic oscillations are always primary and political and cultural oscillations secondary. These secondary, induced oscillations, in turn, affect the primary oscillations through changes in communal psychological attitudes and people’s behavior—another demonstration of the cyclic, coupled nature of these phenomena. Oscillations in all social systems formed throughout history always tend to increase in amplitude. Perturbations growing more and more severe typically leads to the destruction of the system by revolutionary forces that oppose the effort to save and preserve the existing structure in an unchanged form.

Three methods have been employed to suppress oscillations in an unstable social system. The first two use force in a system that has been basically unchanged; the third destroys the existing system and creates a new social structure by recombining its elements either impulsively or according to a preconceived theoretical plan. As a rule, any such plan presumes the new system to be linear or at least close to linear. We are going to describe briefly each method. The first uses feedback with “excessive correction.” When the negative phase of an oscillation induces pressure “from below,” from the masses, this method responds with greater force “from above,” from the authorities. In a capitalist system, we label this protective response to oscillations as fascistization of the society.

If the elements of a social structure were objects and not people, the only reason to criticize this method would be its technological primitivism, like that of an energy-producing machine that uses some of the energy it produces to dampen its self-induced oscillations, which results in less energy that can be used for other purposes. In this analogy usable energy represents social activity whose aim is to satisfy people’s needs, while the energy used for dampening the oscillations corresponds to activities that serve not to meet people’s needs but to preserve the existing social structure. Because the elements of the system are people, fascistization means not just a mere waste of social energy, but more importantly, a violation of personal integrity in the name of preserving the integrity of the social structure. But the constituents of the vast social system network are the neuronal networks of individual people, and so to keep the higher-level network stable, personal freedom and the developmental potential of individuals are sacrificed. As we know, this method, i.e., the use of force, turns people, neuronal networks, thinking and autonomous units, into passive, mechanical elements, which is the worst thing that can happen to a network-type system.

In practice, the use of force to stabilize a capitalist structure is not revealed to a society as such. Rather, a metaphysical doctrine is created to conceal the real goal behind many spurious ones, which justifies the actions taken. The doctrinal goal may be single—external expansion needed to address an alleged lack (e.g., of a “living space”)—or they may be multiple—doctrines based on discrimination and segregation of the members of the society into “the better” and “the worse,” etc. The arguments range from pseudoscientific to utterly irrational (such as the nation as a mythical union of blood and land), but the purpose is always to get people to accept the imposed situation. From the cybernetic point of view, this is a case of having surrogate goals replace real ones, so it is a social pathology analogous to the pathology of learning that we encountered in neural networks.

The second method for damping oscillations in a capitalist system is based on planned changes in the feedback delays. It originated from studies by many economists, including Keynes.5

HYLAS Are you saying that these economists already used methods of cybernetics to solve economic problems?

PHILONOUS Cybernetics was not yet born at the time of Keynes’s school, but yes, in a sense. Keynes created quite a complicated theory, but I will discuss only one of its elements, which is a good example of an attempt to save capitalism by changing parameters of feedback links in the system.

As you know, in nineteenth-century capitalism Marx discovered the law of pauperization of the proletariat and accumulation of capital. This process seemed to have a linear character, and Marx predicted that a series of deepening crises would lead to the eventual collapse of the system. But the process was linear only in a certain time interval, and an intervention changed its characteristics. I have already mentioned the feedback in supply and demand, which causes overproduction, worker layoffs, and the resulting decrease in a market’s purchasing power; the feedback between an increase in unemployment and a decrease in demand thus precipitates a crisis. In the case of a neuronal network, you may recall, we spoke of such divergent oscillation as a “short circuit” or epileptic seizure.

HYLAS So crises are the epilepsy of capitalism?

PHILONOUS Cum grano salis, one can say that. Keynes claimed that the investment rate depends on the profit that producers expect, and those expectations in turn depend on the market situation. Thus the market situation depends on the investment rate, and the investment rate depends on the market situation. Other variables are at play, but at the given capital concentration and production methods the variables that we pointed out play the decisive role. Therefore, Keynes advises that time shifts in elements of the economic processes, particularly the investment rate, which is the easiest to control, should be planned in long-range projections. This changes the parameters of the existing feedback. When a society’s purchasing power decreases, the “investment emergency stores” should open up, which would, at least to some extent, damp the oscillation amplitude. Such a policy of continual intervention assumes the existence of intervening organs. For example, the state, guided by economists who study oscillations in market parameters, might dedicate a part of the budget to large contracts (investments). Note that such investments are made not to meet societal needs but to lessen the threat of an oscillation (a drop in purchasing power).

HYLAS But an organism also possesses “interventional emergency stores,” in the form of its network’s negative feedback, which compensates for all harmful influences of the environment (this is the basis of the regulating of temperature, blood pressure, the chemical composition of the blood, metabolic rates, etc.).

PHILONOUS This is the big difference between a society and an organism. In an organism, self-induced oscillations are abnormal, pathological; in a capitalist system, they are natural, inevitable—all we can do is use “buffering” or “moderating” tools, of which “investment emergency stores” is one. The economic situation of a society is a resultant of a large number of factors linked by feedback. Economists’ forecasts and state interventions work to regulate this situation, to keep it in relative balance. Any change in production methods or in the environment (world markets) can disturb it.

HYLAS How real is this threat?

PHILONOUS The real danger now is the “second industrial revolution,” the mass automation of production processes, which has begun in our time. Automation leads to a drop in the price of the final product, because automata work faster and are cheaper than human beings. The interest of the consumer here coincides with that of the producer: the former wants to buy cheaper, the latter wants to produce cheaper. But automation also leads to unemployment, which in turn reduces a society’s purchasing power. For this reason, automation has so far been conducted in the United States with caution and below capacity (barely 10 percent of factories have been automated, and less than 6 percent of the total capital has been invested in automation), to keep the negative feedback from becoming positive. Yet a society in which the means of production remain private property cannot achieve full or even major automation, since owning an automated factory makes no sense: the producer cannot expect a profit if nobody works in the factory and therefore nobody earns the money needed to buy the product. Thus automation undermines the system’s fundaments—private investment and the circulation of money and goods. Capitalism has not yet reached the critical stage of automation, but it will happen within two decades. At present, investment returns coincide to some extent with societal interests, but a change in the system of production will make the two diverge. Progress in technology threatens the system’s stability. American economists are working hard to solve this problem but have not yet succeeded.

HYLAS Indeed, the future of capitalism does not look rosy. But at present you consider it stable enough, owing to its control over the economic oscillations, right?

PHILONOUS An organism is an original, primary entity, irreducible to anything else, whereas a society is a secondary phenomenon. The interests, so to speak, of an organism’s parts must be subordinate to its existence as a whole; it would be nonsense to say that a leg or a lung is more important than the body it belongs to. But the subordination to society of an individual’s interests should happen only to the extent necessary for the individual’s benefit, for his freedom and well-being. Of course, the term “necessary” can be filled with various contents. Here we enter the difficult realm of normative systems, which do not require justification. What are or should be the goals of an individual? What is society allowed or not allowed to do to an individual? For what purpose does a society exist? In considering questions like these, we step beyond the bounds of both cybernetics and sociology. We are asking not what is taking place in a society but rather what should be taking place so that its members can be happy. Cybernetics, like every other science, is silent about human happiness. But once we have established, on the basis of a free choice, what constitutes the fulfillment of human needs and the broadest limits for the fullest development of individual freedoms, we can address cybernetic sociology with the following questions: Does this particular societal structure guarantee people the given rights and the given number of degrees of freedom, and can this structure even be realized? Are its dynamic laws linear over a long time or are they nonlinear and therefore predictable only in approximation? Will the structure be internally stable or not? Will it show developmental tendencies toward the loss of equilibrium, toward a reduction in degrees of freedom, or toward self-induced oscillations? Should it be protected against detrimental changes in its parameters? If yes, then how? It may turn out that the ideal structure cannot be realized; or maybe it can, but its developmental characteristics will have serious drawbacks; or the structure will be stable for, say, a century, and then will succumb to degenerative tendencies. And after long deliberation we may choose another structure that does not meet all our criteria but includes greater possibilities for development and guarantees the emergence of such long-term societal automatisms and linear processes that will spontaneously steer it toward states with increasing numbers of degrees of freedom.

I hope it is now clear that capitalism cannot be this structure, not only for moral reasons (which demand condemnation of the exploitation that is inherent in it), but also because of objective characteristics of its internal dynamics, which hinder technological development toward full automation. Capitalism’s use of economic means to dampen oscillations may be less costly in human terms than the physical violence used by fascism, but the consequences are still negative in all spheres of life. The work of von Neumann showed that the dynamics of social processes have the character of a game (in the formal, mathematical sense).6 Everybody who lives, and chooses to do so, in a capitalist system must accept its rules of the game, which are ruthless. No one asks you if you agree with those rules or know how to use them. Whoever does not know or refuses to follow them must be destroyed. Economic perturbations and oscillations in market feedback decide human fates. Everything that has value, by virtue of that fact, becomes goods. A ceaseless economic war is raging, and the stronger people, not the better, are the victors. A prosperous capitalist country like the United States is similar to a heat engine in that it can function only if a difference in temperature exists. The heat in the boiler by itself cannot do anything until it is conducted to a place with a lower temperature. Therefore, every heat engine must have a cooler or condenser; for the States the “cooler”—or heat sink—is foreign markets and colonial countries. Capitalism requires and maintains unequal development, because, as we noted, what is best for society is not always profitable. We could expand this critique by showing the relation between the authority of the state and economic processes, proving the secondary nature of that authority and demonstrating how negligible effect it has on the general direction of social life. But none of that can alter the negative judgment of this system expounded in the works of Marxist sociologists. Therefore, let us turn instead to the search for the ideal social structure. It is not a simple task, and we lack the knowledge to arrive at any concrete, detailed model. Even so, building such a system is within human possibilities—important in the twentieth century, a time of great hopes and great disappointments.

HYLAS An ideal society being one that meets all our requirements—which we must define first, on the basis of our beliefs and worldview? And we must decide on an acceptable range of individual freedom, yes? Hence: freedom to act, without diminishing the same freedom of other members of the society; freedom to develop personally, to be oneself, and to exercise one’s talents; the maximum possible fulfillment of all life’s needs. All of this, naturally, regardless of one’s origin, birth, race, or nationality.

PHILONOUS It is hard to disagree with you, and yet—no matter how paradoxical it may sound in view of what was just said—I would begin our discussion of the “ideal system” not from the individual but from the society, or perhaps from both sides simultaneously. Instead of adopting your focus on personal freedom, let us consider all mutual interactions among people simultaneously. Human abilities and characteristics complement each other not only in the economic sphere but in all spheres: creative work in the sciences and arts, family life, friendship, and love. The degree of this mutual complementarity tells us about the stability of social links; the degree of personal freedom tells us about the developmental ability of a society. The highest level of both—that is the formula for our model. Such a society develops not by simplifying the existing links and its structure, not by subjugating its members, but on the contrary, by increasing the complexity of its structure. The more information circulates in a network, be the network neuronal or electronic, the more activity fields, and the greater variety of needs, talents, occupations, and tastes it has. It is precisely this differentiating and fragmenting dynamics of the ideal model that counteracts the emergence of oversized and ossifying institutions, which regularly appear when human groups organize on the principles of hierarchy with features of socially harmful automatisms (in contrast with beneficial automatisms, of which we will speak later). Any individual ambition must find a societally organized outlet and a path to its maximal realization, possibly transforming societally harmful tendencies into beneficial ones along the way. Therefore, an individual’s growing responsibility for himself and his fate must be accompanied with an increased feeling of connection and complementarity with others. Only a structure that takes into account the interests of both the whole and its parts can ensure both the free development of individuals and the growth in adaptability of the society, so that the society can change in response to its environment, whether the environment is local, global, or even interstellar. This is how I see the ideal model, my friend.

HYLAS But this is not a model, just a list of criteria that you submit to cybernetic sociology, which will determine whether or not this set of parameters can coexist in the same structure. What is the next step?

PHILONOUS True, my proposal does not define parameters as measurable quantities, which cybernetic sociology needs if it is to find, out of thousands of possible variants, the model that best meets the criteria. We are very far from such an undertaking, as we are very far from assembling a blueprint for the proposed model, since cybernetic sociology itself is still only a set of postulates and observations, not a fully developed branch of science that can be applied.

HYLAS Are there fundamental laws that govern a society?

PHILONOUS One can call any law fundamental, just as one can say that human nature is naturaliter christiana or naturaliter socialistica.7 But this is arbitrary, a fetishization of laws, and does not bring anything new to the table.

HYLAS Marxists say that the fundamental law of capitalism is the pursuit of maximum profit. Are they wrong?

PHILONOUS No, but that characterization of the system is insufficient. Observe the form of a statement offered as an objective social law. “Pursuit of maximum profit” clearly points to purposeful activity and implicite assumes there is feedback in the system. “Pursuit of the maximum satisfaction of people’s needs” also assumes there is feedback. Laws of social systems differ from those of material systems, such as collections of atoms or stars, in that social laws must include feedback and therefore have a purposeful character (even when no one is aware of the purpose), whereas material laws do not. All social systems thus belong to a class of networks that have feedback and are capable of purposeful action and learning (see the rise of national cultures).

HYLAS And what does a cybernetic analysis of a socialist system look like?

PHILONOUS All social systems in history arose spontaneously, but socialism, an attempt to construct a society based on known laws, did not. Marxist historical materialism defines a fundamental rule common to every social system: the formation and organization of interpersonal relations are dependent on the method of producing goods. This law is as universal as the laws of thermodynamics. Just as a machine that obeys the laws of thermodynamics may be efficient or not, capable of economical and long-lasting performance or not, a social system that obeys the Marxist law of dependence between the two relations may be internally stable or not. A necessary condition for building our new system is the socialization of the means of production, because private ownership, as we have seen, gives rise to socially harmful economic oscillations with repeating periods of unemployment and subordinates individual lives to the economic law of value. Moreover, in the long run private ownership does not permit automation and consequently blocks progress in the methods of production. But if this socialization is a necessary condition, it is not sufficient to guarantee the natural, noncoerced stability of our new system. There are many possible ways to organize socialistic production, and not every one of them sets into motion the social automatisms that would ensure success. Therefore, experimentation is critical for choosing the right model.

HYLAS What do you mean by noncoerced stability? And what are the “social automatisms” that you mention?

PHILONOUS Any system exhibiting divergent self-induced oscillation, such as capitalism, can be made stable by the use of force. Without force, the oscillation, increasing, will bring the system down, like an unbalanced machine that comes apart because of runaway vibration. The force applied can be physical—in fascism, for example. It can also be economic—capitalism uses that kind of pressure (the effect of the law of value) to keep the social structure stable, but there can be a physical component as well (in dealing with labor unrest). The “ideal” system should, naturally, refrain from the use of any force.

Except that the construction of our new system must begin within an old system and it has many unprecedented features. The first is the necessity to overcome the resistance of those who wish to maintain the old system. No other construction work takes place under such conditions. That resistance cannot be overcome without force. The second feature is that the constructors of the new system cannot remain outside of what they are building, unlike the constructors of conventional machines. The boundary between the constructed and the constructing disappears in this process. The third feature is the use of people as construction elements, which makes the constructors’ actions subject to moral evaluation, which in general is not the case in other construction projects. The fourth and final feature is the simultaneous operation within the system of two kinds of laws: established and objective. In conventional machines, only objective laws operate. Both kinds of law have feedback, but the principial difference is that an established law can be violated without affecting the whole system, whereas with an objective law this is not possible. Therefore, an established law carries with it penalties, which an objective law does not need. The relations between the two are complicated. The functioning of an objective law can be changed by an established law if and only if the established law brings about a structural change in the system (e.g., a vote on the nationalization of industry and land turns a capitalist system into a socialist one).

HYLAS I don’t understand. How can any established law violate the causal dependence of interpersonal relations on production relations?

PHILONOUS Yes, this fundamental law of society is universal, as we said. But every machine, besides being subject to the laws of thermodynamics (e.g., we always take from it less energy than we put into it), also exhibits many regularities specific to its operation. And the dynamic rules of a social system correspond to these operational rules of a particular machine. If this machine does not exist, its operational rules obviously cannot manifest. Only when we build it, according to a plan, the rules may begin to manifest themselves.

HYLAS Why do you say “law” sometimes and “rule” sometimes?

PHILONOUS This differentiation stems from what we might call “constructor empiricism.” If we knew absolutely all the objective laws in a certain field—e.g., the laws that govern atomic transformations—then we would not need to resort to long and troublesome experimentation but could deduce from the totality of these laws the best blueprint of the thing we want to build (e.g., a nuclear reactor or engine). In practice, however, our knowledge is never complete. Einstein’s theory of gravitation explains facts that the previous Newtonian theory could not, but it does not explain all the facts. In the future there will emerge a theory of gravitation that corresponds even better with what we observe in the real world. And so on, forever. Important for a constructor are not only the laws he already knows but also the laws he does not yet know or, what comes to the same, unforeseen consequences of the laws that are already known in the field. When airplanes were built on the knowledge of aerodynamics, the engineers could not avoid problems caused by the unforeseen induced oscillations in the structures. In general, every constructed device exhibits regularities in its operation, some of which are foreseen, and in fact desired, by the constructor, and some of which result from laws that are not yet known or are known but were not taken into account. A theorist who studies collections of atoms or stars knows that his predictions based on the application of a law in its current form will not be matched exactly by what really happens. A constructor cannot accept that; instead, he uses trial and error, empirically studies all the regularities exhibited by the device under construction, to arrive, through the elimination of what doesn’t work, at the project realization that will be satisfactory. Knowledge of the general laws of a system, which in practice is always incomplete, is therefore insufficient to unequivocally guide a constructor in his work. One can say that a constructor acts with incomplete knowledge of the objective laws that govern the device he is constructing. And if this statement applies in some extent to all areas of technological effort, it does so especially to the area of sociological construction, where our knowledge is still relatively meager. This is the first reason for making a distinction between laws and regularities-rules.

The second reason, also empirical, is the difficulty of deducing the specific operational rules of a device from general objective laws. Every refrigerator is subject to the laws of thermodynamics, and yet those who build refrigerators deal very little with the abstract laws of thermodynamics; they pay much more attention to the technical properties of cooling devices, that is, to the rules of their operation. A detailed consideration of the scientific problem that we are discussing here would require time and extensive research, neither of which is at our disposal. For our purposes, the two differentiating aspects that we mentioned should be sufficient. Thus the universal sociological laws apply to all social systems, but those systems also exhibit in their functioning specific regularities dependent on their structure.

If the flywheel of a steam engine is incorrectly engineered, and therefore unbalanced, and the machine breaks into pieces due to centrifugal forces, it is a manifestation of the laws of mechanics but at the same time a consequence of the given construction and the effects that are specific to it (e.g., the resonance vibration of some of its parts), and we call this a regularity or a rule that all the engines built from the same blueprint will manifest. The imperfection that induced the vibration can be removed by making changes or improvements in the blueprint, which obviously does not change the universal objective laws governing the machine. In the same way, we can remove certain negative phenomena that manifest in the functioning of a social system by changing its structure, which can be achieved with the help of an established rule. The point is that the established rule should address the true and objective causes, the systemic source of the problem, not merely mask the observed perturbation.

HYLAS Mask?

PHILONOUS Meaning to cover up, camouflage. An established rule that operates, that is, is obligatory, in a system can make it difficult to discover the objective dynamic law of the system.

HYLAS You have lost me.

PHILONOUS Imagine a traveler on a ship on the ocean. There is a storm, the ship rocks, the traveler becomes seasick, which is a manifestation of objective rules of physiology: the motion stimulation of his cochlear labyrinth causes, via a reflex pathway, cramping of the stomach with familiar secondary results. But at the last moment the traveler suddenly learns that the ultimate manifestation of seasickness on this ship is punished by death (for such is the rule established by the captain). With tremendous exertion of willpower our traveler will refrain from “feeding the fish.” We have here a suspension, at least apparently, of an objective law by an established rule, without any change in the system. Speaking more generally, people may become seriously ill but, under the threat of punishment, manage to prevent the illness from manifesting itself. In this way authorities can mask the effects of certain objective regularities in social dynamics.

HYLAS I see now. Yet your traveler might be unable to hold back the manifestation of his seasickness. But that is probably beside the point . . .

PHILONOUS This is precisely the point, my friend. You have put your finger on it. The objective laws of organisms, both biological and social, or, even more generally, the operational rules of systems with feedback, are not strictly deterministic but statistical, and that is the reason they sometimes seem to be violated. The traveler will probably but not certainly keep from “feeding the fish.” As for the statistical nature of the rules of social systems, a summation of a large number of individual processes results in a significant regularity with only rare exceptions, so we can make predictions of how individuals will act. We may indeed come across a capitalist who, moved by charity or mental illness, donates his factory to the workers, but we can safely rule out that suddenly all capitalists will offer their factories to the proletariat, thereby transforming the social system. Likewise a few individual molecules in a pot of cold water may move with the speed that corresponds to the temperature of boiling, but it is statistically impossible that by chance all the molecules will suddenly move at the same time with that speed, making the water in the pot boil without our supplying any heat.

HYLAS And what about the social automatisms that you have mentioned?

PHILONOUS This topic requires a more detailed analysis of our model. In the capitalist model, the essential independence of the economic processes from the governing processes is evident. The former, dominating the latter, determine the path of the society’s development. Governing links connect the administrative center with the periphery, that is, the society. In contrast, economic links (of production and product circulation, sale of goods) have no center and are always peripheral. It is precisely in economic links, i.e., in the connections between the parameters of supply and demand, that the automatisms of capitalism operate. They appear wherever an individual’s personal interest coincides with societal needs. For example, it is in the producer’s personal interest to react to increased demand by increasing the supply. Yet it is just one part of a much broader issue. A social dynamics automatism manifests in an equilibrium that is established between needs and their fulfillment in all spheres. All societally needed professional positions get filled, even though capitalism principially lacks specialized organs to do this filling. It is the result of the constant “pressure” of economic conditions, which can be compared to the biological “pressure,” that developmental expansiveness that, operating in the processes of organismal evolution, causes life to be present wherever the conditions are right. Or, to give another example, just as we automatically achieve saturation by pouring a salt solution over a layer of solid salt, the saturation of societal needs is achieved by creating an army of reserve workers. The “pressure” of economic conditions means imposing on individuals the necessity of making a living as their personal motivation. In our new model, this motivation should be replaced by a different one—the awareness of the usefulness of one’s labor to society. Admittedly, this is the weakest point in our theorizing, because we are assuming that a person who appreciates the societal benefit of his efforts will work as much and as well as he can.

Production methods today, along with the sharp division of labor, have the consequence that an ordinary worker sees only a very small part of the production cycle. People whose work encompasses a whole cycle—artists, scientists, craftsmen—are the exception. Every worker thus contributes just one drop in the ocean of the society’s work and it is extraordinarily difficult for him to track his contribution to the universal production. The less coerced the dynamic continuity of a social system, the more the interests of the individual, that is, the subjective reason for his activity, will coincide with the interests of the society. The establishment of spontaneous and stable motivation, free from individual perturbations and without the propping factors of personal economic involvement, has been rendered practically impossible by the modern division of labor, which overabstracts individual contributions into the total of society’s production. Our new socialist system makes various compromises to create social mechanisms that substitute for that subjective motivation. But data show that after almost forty years of practice a worker’s effectiveness in capitalism is still higher than that in our socialist system. It obviously follows that the vector of personal motivation, even with those specially designed social mechanisms, does not coincide with the vector of societal needs in socialism as closely as in capitalism.

HYLAS Are you saying that the data prove the superiority of capitalism over socialism?

PHILONOUS I would not jump to that conclusion. The efficiency of current gas turbines is lower than that of a combustion engine, yet experts agree that the future belongs to jet propulsion. The point is that the existing constructions need to be improved. But before talking about improvements, let us take a closer look at the mechanism of these phenomena.

The studied system has both the centralization of power and the centralization of production control, which is why we name it centralistic. During its operation, it manifests regularities that the plan has foreseen, such as the lack of a reserve army of labor and an increase in real wages, but also regularities that the plan has not foreseen, in particular certain long- and midperiod oscillations. Oscillations in production may be hidden, showing not in the amount of the product but in its quality. They result from an overlay of the oscillating production plans (an initial scarcity followed by an increased effort to fill the gap) and the oscillating market supply (temporary, periodic gaps in distribution).

HYLAS Why do we have these oscillations?

PHILONOUS There are many reasons. The structure of the system shows a tendency to “move the decision-making up the ladder.” The place where a decision must be made, that is, a response to a piece of information (e.g., about the market supply/demand ratio) is formulated, is pushed higher and higher in the hierarchy of power.

HYLAS What causes this strange phenomenon?

PHILONOUS It is an objective rule caused, first, by perturbations in individual motivation and second, by the institutional nature of the organs that control production. Ideally a production plan should take into account the current societal needs but the future needs as well (for example, production of the means of production). In theory these should be two sides of the same coin, but in practice they are not, due to the various length of the feedback links. Hierarchical institutions may serve the purpose for which they were created but also exhibit dynamic regularities of their own, which are manifested in their tendencies toward subordination of individuals and autonomization. The institutions exhibit conservatism and tend to grow and ossify by adhering to the same mode of operation once it has been established. By virtue of being a part of an institutional structure, the institution’s members turn into links in information transmission, which decreases their autonomy in decision making. The institution represents the feedback system between demand and supply, but these links are very long in comparison with the numerous peripheral automatisms, which in capitalism consist of producers and consumers whose personal interests shorten the supply-demand connection. In a centralistic system, the links that regulate production are as long as the links of governing, and every link must pass through the center.

HYLAS I’ve heard somewhere that institutionalism has been blamed for the faulty functioning of the socialist model, but I have to say that I am not convinced. Capitalism also has large institutions—monopolies and trusts, for example. It also has public service organizations, which often are large, but they still work with exceptional efficiency and are able to fully respond to societal needs.

PHILONOUS Precisely: they respond to societal needs. Please, note that in capitalism, the constant pressure and the incessant regulatory function of those needs keep the institutions, above all the public service ones, from degeneration and autonomization. In reality, speaking of institutions in general is like speaking of the complexity of neuronal networks in general: it disregards the specific purposes that those institutions (or networks) serve. You already know that excessive complexity can be detrimental to a network, and it also applies to an institution. In evolution, the regulatory factor is natural selection, a selective function of feedback that eliminates every biological construct that does not serve the preservation of the species. In capitalism, an institution that does not bring a profit (e.g., an overbureaucratized travel agency) automatically disappears because it goes bankrupt, just like a species that loses in the battle for survival goes extinct. In the centralist model, institutions are not subject to that criterion or pressure by real, objective conditions. They continue growing in size and complexity.

HYLAS Why?

PHILONOUS Over time, in the relatively small group of those who govern, there emerges such a concentration of production-regulating feedback links that the group’s “information capacity” exceeds its limit, which necessitates a further expansion of the central apparatus of governing. Such a system is like an organism that, deprived of its automatisms, i.e., reflex centers, must consciously and with focused attention regulate the beating of its heart, the pressure and chemistry of its blood, its breathing, the processes of tissue metabolism, and so on. Such an organism would be unable to do anything besides maintaining its own life processes in a semblance of equilibrium.

Centralization, excessively increasing the density of feedback links, blocks (or at least impedes) information transmission and at the same time lengthens its pathways. Instead of direct connections between supply and demand, hierarchically layered “relay stations” appear in the system, and the delay between stimulus and response increases. And we have already explained the role of a delay in a feedback system. In capitalism, the delay in production processes, that is, the time interval between a change in demand and the resulting change in supply, has a crucial effect on the oscillations; in the socialist model, the delay caused by the lengthening of feedback pathways (periphery—center—periphery) is the most significant.

When a delay between stimulus and response is similar to the time interval in which the stimulus acts, it becomes an essential parameter of the system, that is, it begins to actively affect the processes in the system. An example is a film: the impression of movement that the audience has is due to the frequency of the stimuli (frames on the screen) approaching the delay in the reaction of the neuronal networks of the audience. A similar phenomenon in a social system is responsible for phase shifts in the production cycles of factories that cooperate in making the final product; if there is no buffering reserve of intermediate products, the result will be dissociation and desynchronization of production. This causes factory downtimes and depressively affects the powerless workers, which only further decreases labor efficiency. A kind of vicious circle has been created.

HYLAS Wait. I have just realized that “centralization” exists in an organism too, since reflex centers are subordinated to the nervous system. Also, doesn’t a social automatism exist in the capitalist system, which through the functional anarchy of its elements gives rise to oscillations?

PHILONOUS Yes, it was a simplification when I spoke about an organism. Functions that an organism performs as a whole (e.g., the search for food) are indeed always governed by its “centralized” nervous system. These are mainly processes that govern the relation of the organism to its environment. But in the area of internal processes, the reflex (vegetative) centers and local muscle automatisms play the crucial role, and they operate on the basis of feedback between cells and tissues. The loss of connection between any part of the organism and its central nervous system does not lead to a local disintegration of function or manifestation of tissue antagonisms—precisely thanks to this local correlation. Only a disintegration of the local feedback links, which shows in the form of unregulated, unhindered growth, that is, neoplasia (cancer), poses a threat to the organism. Thus it is a consequence of feedback disintegration not on the highest level, i.e., in the central nervous system, but on the lowest, peripheral level. As you can see, even organisms that have been evolving for billions of years are not completely safe from a breakdown in an inner functional correlation. In this light, the enormous difficulties that the constructors of social systems face become more understandable. A hierarchical institution’s tendencies toward an unlimited growth and an emancipation from the regulating effects of the social organism is indeed analogous to tissue cancer, but I do not think that analogies like this have any cognitive value, given the differences between the two types of system. In particular, the two have different goals, and their construction elements are not the same: while the elements of a social structure—people—represent autonomous values as individuals, the elements of an organismal structure have value only with regard to the organism.

Capitalist automatisms do regulate social dynamics ad hoc by influencing individual motivations for action, but at the same time, through feedback links, they can cause long-term disturbances in social dynamics. Here I am neither praising nor criticizing, only describing.

But let us return to the topic. We have discussed how oscillations are induced by the concentrating and lengthening of a system’s feedback links and by the weakening of the individual motivation to act. The authorities counteract the dangers of not reaching a production goal, of neglecting some production areas for others, of lowering labor efficiency, and other related phenomena, all of which ultimately result in lowering product quality and quantity, by putting into action a special “administrative-persuasion” apparatus. It persuades people to do things and thus takes place of internal motivation. This is why every increase in production, whether it be sowing, skimming, or harvesting, requires a battle cry and a campaign to create the impression that a universal and extraordinary effort is made for the good of the society. As social automatisms and subjective motivation fade, the authority changes from an organ that plans and regulates into an organ that intervenes in every production cycle or even in every area of social and cultural life and through a barrage of instructions, promises, slogans, directives, and prohibitions exerts administrative pressure on its citizens. The people engaged in this activity are not producers but supervisors of the production. They form a structure similar to the hierarchical pyramid of the machinery of bureaucratic administration. The necessity to constantly focus the general effort and attention on the issues of production turns the means for achieving the goal of satisfying the needs into an autonomous goal.

A capitalist producer whose goods do not satisfy societal needs endangers his existence. This danger automatically informs all his efforts, so that ultimately his personal interests will coincide with the demands of the market. A socialist producer is supposed to meet the target of a plan, and the judgment on whether it satisfies societal needs is not his. His meeting the target does not always satisfy societal needs, and when it doesn’t, the feedback link between supply and demand is weakened again, only this time the weakening is not central (in the bureaucratic apparatus) but peripheral (in the factories).

The construction plan does not foresee the phenomena described above, and thus instead of studying and analyzing them as dynamic rules of the existing structure, it systematically disregards them. What the plan in a centralist model does foresee is the equivalent of the “system of stimulus preferences” in a neuronal network, but only the information consistent with the plan is permitted to circulate freely in the feedback system that the authorities maintain between themselves and society (press, radio, official releases, etc.). However, as we know, an organism will change an old system of impulse preferences in response to new experiences, otherwise it would not be able to survive. In the centralist model, the authorities expend a great deal of effort and means to keep the original preference system, that is, the original production plan, intact. They ignore the rules of social dynamics that were unforeseen and yet became evident. Whatever is not consistent with their preference system is blocked and sequestered beyond the reach of the feedback that operates between the authorities and society.

HYLAS What exactly is blocked?

PHILONOUS Various kinds of information: people’s dissatisfaction with the scarcity of certain goods and also dissatisfaction with the official (i.e., by the authorities) demand to express satisfaction because that is what the plan did foresee; certain results of scientific research (note that cybernetics itself was off-limits for a while); news of the detrimental effects of the overgrowth and functional changes in the governing machinery (bureaucratic and repressive); news of perturbations in agricultural production, and so on. The greater the gap between actual information and what is postulated by the plan, the more effort is needed to mitigate the societal consequences of the phenomenon. Let us take a simple example. A person turns on a steam engine without the Watt governor (which is a simple self-regulating device based on feedback) because he is certain that the engine will work without any problems. But in the absence of the automatic regulation of its operation, the engine speeds up until vibrations threaten its whole structure. The person at first tries to ignore it, pretends that “everything is running smoothly,” and claims that the engine is all right. But seeing the increasing vibrations and aware of the danger, he begins to reinforce the machine with iron bars. When that doesn’t help, he decreases the steam intake. But now the engine is running too slow for its purpose, so he must increase the intake again. The closing and opening of the valve repeats periodically. The perturbations of the engine’s operation and the self-induced vibrations—these are the oscillations in the production parameters of the centralist model, and the person’s reaction is the reaction of the authorities of the model. The system, then, also manifests oscillations of the second kind, in the political hesitations: the periodic broadening and narrowing of the limits to action and thought in governing, producing, science, culture, and so on. This vicious circle results from self-induced societal oscillations on the one hand and the delayed and hesitant response of the authorities on the other. When the cumulative effect of many phenomena that were unforeseen by the plan reaches the limit and “exceeds the excitability threshold” of the authorities, they intervene to stop or at least diminish the oscillations (“deviations”) by any means at their disposal. But because they address the consequences and not the causes, their intervention only has a temporary effect, yet it seriously affects psychological responses in people who are the system’s elements.

It is remarkable that so far no theorist has attempted to find in the periodicity of these oscillations an objective rule that would be a consequence of the system’s dynamic structure itself. Instead, explanations of “distortions” and “deviations” have always employed a subjective-psychological terminology: in the “tightening” phase, “dogmatism,” “doctrinism,” or “commandeering” operate, in the phase of “release,” “oversensitivity” or “petit bourgeois attitude”; the avoidance of decision-making by pushing it up the bureaucratic ladder results from “securantism” or “comfortism,” a fear of disrupting the production, and the “bureaucrats’ callousness”; noting negative phenomena in life is “slandering” and pessimism, and so on. But it is not surprising after all. These are words of a specific language whose purpose is not to explain phenomena in a scientific manner but justify or interpret them in a way that is consistent with the plan. As the gap between the societal facts and the a priori claims of the original plan widens, the apparatus of this ad hoc constructed language must grow as well.

Remember the story about the tribe living on the plain that I told you in our third discussion? Their discovery that distant objects disappeared beyond the horizon was a consequence of the Earth’s sphericity. But the people who disagreed with this scientific explanation had to find another—for example, magic: the distant objects were snatched by “unclean powers.” In the socialist model, such an “unclean power,” responsible for everything that doesn’t work, is “the remnant of capitalism in people’s minds.” This creation of a language that falsifies the objective character of phenomena in the system is a typical psychological response of the people who must live in it. As a consequence, the scientific plan for the organization of a new society slowly transmogrifies into a set of dogmas that, like a religious faith, cannot be disproved by experience. Another psychological consequence is that decent and subjectively honest people turn into cruel tyrants.

HYLAS This is strange indeed. Are you saying that the cause of this is the objective rules of a social system? How is that possible?

PHILONOUS As a rule, the people who commit various transgressions, abuses, or even crimes in the name of the authorities were once, before doing injustice to others, revolutionaries who spent years fighting for justice with heroism, determination, and loyalty to the idea, the characteristics that we usually do not associate with tyrants known from history. Don’t forget that the creation of a new system requires the use of force to overcome the resistance of the expropriated classes. The theoretical plan foresees this violence but assumes that, as the new system strengthens, the need for it will go away. The plan does not foresee any oscillations, which, as it turns out, also can be stopped by force. At the beginning, the distinction is clear: repression is used against the enemies of the new, better system. If there are any oscillations in this initial phase, they are negligible. No force is required to deal with them; often persuasion will suffice.

HYLAS Persuasion?

PHILONOUS The elements of our construction are people, not inanimate parts in a machine. This we should not forget. The captain of the ship with the seasick traveler in the example I gave you earlier says to the traveler when the waves are still not that rough, “Sailing is wonderful. You will love it in no time. The rocking, once you become accustomed to it, is quite pleasant. And we will soon arrive at a marvelous port. Suppress your malaise, please, and rejoice in the prospect of our future!” Eventually such appeals will have no effect. When in the face of all directives and prohibitions, the oscillations increase, the authorities will not restrict themselves to persuasion, appeals, and incentives, and focus all efforts on those parameters that changed most threateningly. This “mobilization” improves the values of those parameters, but addressing the symptoms instead of the causes unintentionally activates new feedback connections or amplifies those that have not been evident. After some time, this leads to new perturbations. And they grow. This is the time when the first step is usually taken, the first reshuffling in the machinery of power, by which repression of enemies of the system imperceptibly transitions to repression of friends. The coercion apparatus was already in place—this is very important. A small change in the direction of its application is all that is necessary.

Suppressing the enemy’s resistance is an unavoidable necessity. Enemies operate in various ways; why can’t they also cause the drop in agricultural production or labor efficiency? Hence the distribution of regulations and decrees begins with an intended purpose of removing harmful symptoms from social life. Established laws begin to mask objective laws. On the violently rocking ship even the threat of death cannot stop the sick man from “feeding the fish.” What is left then? Only one option: to gag his mouth. Simultaneously a vocabulary is created to justify each consecutive step on the path to coercion. In this way, the machinery for defending the new construction from enemies slowly turns into machinery for maintaining stability at the expense of freedoms and friends. This is a sequence of actions by which every ruler becomes a tyrant. The new language leaves no doubt. Voices of dissatisfaction and manifestation of protest are labeled as voices of enemies and instigators and calls for changes as calls for the return of the old system of social injustice. Step by step, this can lead to the worst crimes against humanity committed in the new system. When the issuing of consecutive established laws intended to dampen the oscillations becomes too obvious a violation of the original plan (which promised to increase freedom and not the yoke) and can no longer be “justified,” the issuing of secret decrees commences and secret actions are taken that violate the existing laws and constitution. The aim is always to preserve the official version of phenomena and to prohibit a revision of the forecasts that were wrong. No lawbreaking can be found in the officially permitted information. Therefore, more and more areas of social life are declared state secrets, which covers up the actions aimed at saving the integrity of the system at the cost of individuals’ freedom or life. There is no trace of a “tyrannical whim” here; the process is logically continuous and consistent, because there are always only two alternatives: stop the oscillations by violence or change the structure of the system itself. Since the latter is out of the question, the use of force is inevitable.

This situation promotes the forming of different viewpoints in the group that is the focal point of all the feedback links in the system and makes decisions regarding all the parameters of economy and governance. The main fault line runs between those who think that the increasing use of force is unacceptable and that changes should be made in the existing structure and those who demand the use of force with no restriction. “Deviation” is obviously a relative term, but it will be used to label those who lose the power of decision-making, that is, who are removed from power. We must stress that it is not always the advocates of structural changes who are objectively right, since some changes could worsen instead of improve the situation.