VIII

PHILONOUS We discussed the construction of a society, tacitly making the simplifying assumption that all people who are the building material of such construction have essentially the same characteristics. Today we discard this simplification and examine what makes one human different from another. The subject will therefore be the structural quality of a social system, which more or less corresponds to the study by regular engineers of structural suitability and material strength. The motivation for our discussion is your last statement, which may have been a not entirely conscious expression of intellectual snobbery. You saw intelligence as a criterion for categorizing people, making that value judgment as if it were a fact. You went so far as to deny the designation of “human being” to one who does not reach a certain, not clearly defined, intellectual level.

HYLAS Isn’t this criterion just and objective? Is it not obvious that a person should occupy a place in the social hierarchy, or an occupation, according to his abilities, intelligence, and talent? Don’t you consider this to be an ideal for any social system? Is it not a fact that humanity owes its progress to people who distinguished themselves by their intellectual abilities and intelligence? Is not all human culture the product of intelligence, and therefore should not intelligence be considered the most valuable human quality? What in your opinion is a better criterion for categorizing people?

PHILONOUS First we need to answer the question whether criteria for categorizing people in the way that leads to a value hierarchy, according to which some people are more valuable and some less, are necessary, and, if they are, what goal they are supposed to serve. You spoke about such differences to justify the necessity of the biological transformation of our species. It is a bold and exciting idea, but surely it will not be realized in a future that can be foreseen with just a minimum level of rigorousness—because we lack the necessary knowledge, if not for anything else. Consequently, masses of people with average abilities will continue to live and share the same social system, for a very long time, with a great many people who are below average. This is a simple fact. But if we make these differences the guiding principle of our social engineering, it will only lead to the development of yet another theory of social elitism—this time based on intelligence—with the shameful result that intellectually disadvantaged people will have their rights curtailed, unless we consciously and actively prevent it from happening. And we can never be sure if some zealot of rationalism and a worshipper of intellect will not eventually come up with the radical idea of depersonalization camps, perhaps even extermination camps, for the so-called imbeciles with whom, according to you, the world is swarming.

HYLAS I did not say or even think such an awful thing, Philonous, and you should not attribute to me such monstrosities.

PHILONOUS I am not attributing to you any methods or thoughts, Hylas, merely taking what you said to its logical conclusion. You could be blamed for the mentioned extermination proposition just as the theorist and philosopher Nietzsche was for the practices of Nazism. The biological reconstruction of human beings is, for now, a fiction, yet your words, though meant only as a complaint, pointed to segregation of humankind, in which the feudal criteria of birth, the capitalist—of possessions, or the Nazi—of race, are replaced with the criteria of intellectual ability, but it can only end up valuing some people over others. I vehemently oppose this. Any construction of a social system that enables the establishment of a privileged elite must have nothing to do with our aspirations and explorations.

HYLAS Your opposition has little justification if it only stems from causes that are emotional and moral in nature. Moreover, it contradicts the objective fact that intellectual differences do exist.

PHILONOUS Of course, my opposition is on moral grounds. As we said, social engineering must be subject to ethical criteria, because here the building blocks of a system are people. But what I say next is a mix of ideas and facts based on science.

HYLAS Go ahead. I am listening.

PHILONOUS We must first settle, as rigorously as possible, the matter of human intelligence. For ages people have been debating whether intelligence is an inherited or acquired trait. Research, particularly from the last decades, suggests that intelligence, that is, the maximal intellectual effectiveness that enables a person to handle all kinds of professional and life situations (obviously, this is not a rigorous definition!), is determined by both genetic and environmental (epigenetic) factors, the genetic having greater weight (although some utopianist socialists don’t want to hear that). At least in principle, the differentiating effect of the environmental factor can be eliminated so that we obtain a state determined purely by heredity. In a society with a significant degree of structural inequality, in which the privileged classes hinder the development of those from the lower classes, the average intelligence in the lower classes will always trail behind that of the ruling classes, but it is for environmental, not hereditary, reasons. The further the progress of democratization, that is, the process of equalizing the starting position in life for all members of the society, the smaller that difference will be. A limit to this process is a state (which has not yet been achieved anywhere on earth), in which environmental factors will have practically no effect on the statistical distribution of intelligence in the population.

HYLAS No effect at all?

PHILONOUS No, I said they would not affect the statistical distribution of intelligence in society. In other words, they will cease to act as differentiating factors. When an environmental factor influences everyone equally, it stops making a difference. Where a selection based on belonging to a caste or a race does not hinder access to education, information, and ideas, the environmental factor can be removed from our calculations. It will still be operating, of course, but equally on everyone, and therefore the difference between people in intelligence will be due only to heredity. In this ideal situation the distribution of intelligence would be represented by Gauss’s normal, bell-shaped curve: the largest number of individuals have average intelligence, and the number of those with higher or lower intelligence decreases as the distance from the average increases. It follows that intellectual inequality, having its source in nonenvironmental, inborn, or inherited factors, is a fact that the engineer of social systems must take into account. Rejecting this fact, even out of the noblest motives of humanism and egalitarianism, will manifest sooner or later and lead to significant disturbances in social practice.

HYLAS So, nolens volens, you end up agreeing with me?

PHILONOUS A little patience, my friend. Let us consider where intelligence research and measurements came from, what they are like, and what purposes they serve. They originated in a field called psychometrics. After years of trial and error, experts processed an enormous amount of data from what is commonly understood as tests designed to differentiate people according to certain measurable traits of intellectual ability. It may sound paradoxical, but the usefulness of these tests, that is, their social value, is unquestionable, even though we do not know yet what exactly it is that they measure—there is no agreement among the experts on this. Yet the differences that the tests uncover significantly correlate with practical experience in life. For example, predictions of success or failure in the school performance of young people based on intelligence tests have been accurate throughout the existence of this science. True, the tests do not explain the psychological mechanisms behind intelligence; but the same applies to a thermometer, which says nothing about molecular processes yet correctly measures temperature, regardless of which particular theory of thermal motion the user of the device favors. The tests, exactly like the thermometer, are a measuring tool. There are many kinds of such tools, some of which measure the so-called overall intelligence and some of which test for specific sets of abilities that point to a particular job for a particular individual (e.g., mechanical, clerical, or mathematical skills). This field of study has developed mainly in the United States—in the form of highly specialized branches of industrial and social psychology, professional counseling, and so on. That these tests are now used all over the world in disciplines that could hardly do without them proves their practical value. In aviation, for example, pilot training is so costly, the imperative of having an air force is so powerful, and the necessity of the most rigorous selection is so evident, that tests are used to secure the optimal quality of human resources in this field.

The tests have a high diagnostic value, able to determine quickly and objectively the distribution curve of intelligence in any given society, as well as the mental power of its members (with better accuracy and precision than accounts of lifelong acquaintances). They also have a high predictive value for an individual’s success in a field of study or in a job. The work with children of six has less predictive value than the work with adolescents of sixteen, for whom the predictive value approaches 90 percent, which shows that personal intelligence changes little later in life.

Everything said so far assumes that the administered tests reliably measure certain traits of mental ability and that the subjects are equally familiar with the tests, because a person acquires proficiency in taking tests, and so taking many would affect the score. Of course, there are tests that have little or no value, in which case raw experimental data and their professional evaluation by experts become more important. There are also tests, especially for character and personality traits (e.g., Rorschach) that are not as objective as the intelligence or skill tests, where the results depend to a significant degree on the discernment, insight, and intuition of the examiner, which is obviously a severe drawback.

Let me make a few remarks about the overly bold generalizations and groundless extrapolations based on the psychometric methodology and results often used by psychologists. A methodological analysis of these claims shows that they amount to the stratification of human society according to characteristics that persist in its subsets. In every larger ensemble we find the normal, Gaussian distribution of intelligence. There will always be people with intelligence well below the average and people with intelligence well above the average. The average of the ensemble may not equal the average of the whole society—at a university or scientific institution, for example, the average will be higher than in the entire society. What interests me here are the individuals with the highest intelligence. Psychometricians tend to define a genius not as one who appears rarely and who possesses extraordinary creative ability in a particular discipline but as one whose intelligence quotient is as far above the average as possible. This is a serious methodological error. First of all, there are no “absolute” units of intelligence; a numerical value accepted by convention is the result of mass studies and is therefore related to the statistical average of the data. The application of IQ loses scientific meaning when it is made beyond the statistically probable limits of the intelligence distribution, in other words outside the region of valid experimental data—it is like looking for the Earth’s poles on a map in Mercator projection.1 Second, the tests do not measure creative ability in principle. Attempts at developing a test for creativity have not gone beyond the stage of initial, preliminary, and not too successful experiments. Psychometrics is just a particular kind of measurement, and any measuring tool can be used only within a certain range of parameters. A thermometer that correctly gives the temperature of water will lead us into error if we use it to measure the temperature of a cosmic gas. In the same way, a test designed to examine a statistically common trait will fail if we use it to measure a trait that is practically nonexistent in a society, such as an extraordinarily creative ability.

HYLAS I see the value of tests as a tool for selecting an occupation, but to make the course of an entire human life—by pushing a person into a particular occupational path or, conversely, blocking that path—depend only on answers to a dozen questions given in an examination hall, on a preprinted form in pencil, hardly agrees with the tenet of an individualistic and humanistic approach to people’s problems. It can happen, and surely often does, that a test will indicate an intelligence lower than what the subject really possesses because the subject was stressed or “blocked” during the examination.

PHILONOUS You echo reservations that are now almost classic. It is certainly true that a person’s intellectual abilities and emotional life cannot be separated. If a subject, taking a test to become a high-voltage technician, gets a low score for emotional reasons, we might expect that he will not respond well in a real emergency, such as a power line accident, when quick decisions and actions are required. A test would be inadequate exactly if it failed to reveal such weakness in the subject. In selection, the important question is whether or not a candidate is suitable for a job; the question of why the candidate is unsuitable—whether the reason be emotional or intellectual—is unimportant but can be answered with additional specialized tests, if needed. As for the inhumanity of deciding a person’s fate on the basis of a few hours of testing, I would just point out that the predictive value of psychometric tests is on average four to ten times higher than that of any nonobjective method, though the nonobjective method may be kinder (a letter of reference, the opinion of a friend or acquaintance, etc.). Opposing the results of experiments that count in hundreds of thousands is groundless and foolish.

After this praise of psychometric methods, let me now criticize their use, especially in the United States. My main criticism is that such testing is used for selection in an open system.

HYLAS What do you mean?

PHILONOUS An example of an open system is a biological population. Evolution takes place in it by selecting out less adapted individuals, who are condemned to extinction and will disappear after one or more generations. The system is “open” to extinction, rejection, or removal of the individuals identified as “inferior,” that is, less adapted. A society is open when certain occupations and socially valuable positions in its structure are “protected” by a “test filter” that allows the entry of only individuals who pass the test; those who cannot are rejected like social chaff. In such an open system, tests aid in the formation of an “elite of the capable.” But society should be a closed system, in which the purpose of testing is not to reject or filter out people but rather to determine their abilities. The most important function of a test should be diagnostic, directing people to a particular path of study, an occupation, a career, not filtering out those who are less capable. Systematic career counseling, long-term life path advising, and looking for the maximum of abilities—these are the tasks of psychometrics in a society that is a closed system, where no one is discarded or condemned to permanent unemployment. Only in this framework can testing increase the effectiveness of social processes, optimize an individual’s potential, and thereby decrease the number of personal defeats and life failures.

In the United States, tests are employed according to the open system model: universities, corporations, banks, and offices use them as filters to fish out from the social masses the most capable and most productive individuals; providing professional counseling to the rejected candidates is not in the business’s interest. As you see, it is not easy to use testing in a genuinely humane way, with the motivation of caring about the fate of the individual, in a society where the interests of the owners of the means of production collide with those of humanity as a whole.

But you should not think that selection takes place only where testing is widespread. The discriminating filtering of people for occupations and positions occurs in every social system. Often it is not under anyone’s conscious control; it happens spontaneously when certain fields in a social hierarchy somehow “preferentially attract” people with certain traits and abilities. There is interplay here between the “requirements” of unoccupied positions in a society and the broad range of traits that are available in the population. Certain individual abilities, say, mathematical talent, could not manifest themselves in a Neanderthal society for the simple reason that there was no “social demand” for them. Conversely, a society may have a need for mathematicians or physicists—for example, in connection with a push to automate production—but because of the lack of people with required skills few of those vacancies will be filled. Yet this is trivial. More important is the fact that selection criteria can be not merit-based but instead established by tradition, hence obsolete and having nothing to do with the real, substantive requirements of the vacancies, or they may be dictated by an imposed political or religious dogma.

HYLAS What exactly do you mean by merit-based selection criteria?

PHILONOUS First, even the most objective method, that of psychometrics, is just a tool, and, therefore, as with any tool, it can be used to society’s benefit or harm. For a drastic example of harm, a tyrant uses testing to select the most intelligent citizens in order to imprison or kill them, thinking, not without reason, that these are the people who pose the greatest threat to his regime. Second, in practice selection means privileging certain traits for certain positions or occupations. These can be traits that are truly necessary in a job—imagination and construction skills are necessary for an engineer or architect, mechanical talent and good reflexes for a driver or pilot, specialized knowledge and organizational skills for an agronomist in charge of large tracts of farmland—but there are also less merit-based traits, and these apply to all kinds of managers, for example, the ability to impose one’s will on subordinates, regardless of whether the objective has professional justification or not. Being an opportunist, having a good memory for quotations, eloquence, and knowing how to flatter a superior are other examples.

HYLAS So you are calling traits not based on merit those that serve the interests not of society but of an elite or a ruling group.

PHILONOUS Basically. They can also, if not directly serving an elite, result from a doctrine that the elite is proclaiming. A selection filter of “racial purity” would be an example. A routine application of criteria not based on merit is found especially in centralist systems. Commonly called “cronyism,” it fills all socially valuable positions and occupations with incompetent people, which leads to severe disturbances in the economics and dynamics of the entire system. But note that some resistance to selection criteria not based on merit, resulting from objective developmental factors, is practically unavoidable. If in any field of human activity a change takes place that demands new methods and therefore new skills, the people in this field typically defend the methods and views of the past by all possible means. Take psychology as an example. At the beginning of the twentieth century, mathematical skills did not belong among the traits required for the profession of a psychologist. The spreading mathematization of psychology, related to the revolution in the field sparked by psychometric studies, resulted in a significant change in selection criteria for skills of a psychologist. This makes us understand the distaste for psychometric methods and the mathematization of psychology in general among the psychologists who were trained before the change.

Let me mention one more consequence of discriminating trait selection in society that can determine the life path of an individual. Every system, whether it employs scientific, objective selection methods or the selection occurs spontaneously, contains some people who for various reasons are unable to meet the requirements for any of the available professions or societal functions. I am talking about “misfits,” who can never adapt and are always filtered out. I believe that studying this group will allow us to draw conclusions about the overall value of a given social system, about the selection criteria that it employs, about the conflicts and tensions that typically occur in it, and so on.

HYLAS May I assume that this group usually consists of neurotics and neurasthenics?2

PHILONOUS The composition of this group will be different in different social systems. Misfits are always filtered out, but societies do not all use the same filter. In some, the maladapted may be individuals of high moral quality—for example, in a social system that resembles a Nazi concentration camp. These would be the people who cannot accept social roles imposed by force, who refuse, say, to serve as an executioner of their fellow inmates, or to work in a crematorium or at a killing ground. I am mentioning this just to show you that selection does not have to be based on intellectual differences. Intelligence is just one dimension, and selection in a social system is, as a rule, multidimensional.

HYLAS I understand your point about the multidimensionality of a selection process, but in a normal society the people filtered out are mostly weaklings, in both intellect and character—so neurotics would be predominant there, don’t you agree?

PHILONOUS What do you mean by “normal” society? Is the Nazi system abnormal? In it, the filtered out may be people whom we would consider morally wholesome, yet the selection filter imposed by rulers favors the traits of ruthlessness, blind obedience, cruelty, and intolerance—to the extent that some experts argue that the top positions in such a system are held by sadists and psychopaths. But let us be careful here: reducing a sociological problem to that of individual psychology disregards the influences of a social structure. People can turn into sadists out of necessity, if a forcibly imposed convention demands it, not only out of a personal tendency. The thesis of Kretschmer, that normal people are ascendant over psychopaths in times of peace while in times of revolution and upheaval the psychopaths, becoming dominant in a society in turmoil, rule over the normal people, is undoubtedly false.3 The cause of sociopolitically motivated crime is most often found in the very structure of the existing system, in its objective dynamic rules, whether they result from interclass struggle or the tyrannical behavior of the rulers in a centralist system. Explaining such crime solely by psychopathological analysis is a fundamental methodological error and absolute misinterpretation that harms the progress of science in general and sociology in particular.

As for neurotics, they usually are not born that way but become neurotics mainly as a result of their environment. This issue has a curious social aspect. In general, the prevalence of neuroses increases as a society improves. Indeed, stress and anxiety disorders seem to be a byproduct of a high level of civilizational development. Experts confirm this. It is known that not only neuroses but also severe phobias disappeared, that is, were “cured,” in the concentration camps: anxiety disorders and obsessions subsided in the face of very real and terrible danger. Not that I am recommending this kind of therapy.

HYLAS I have always been puzzled why psychoanalysis, so popular in the United States, is not equally popular in other countries of the West, for example, France or Italy. Can the standard of living play a role here, since, as we know, it is the highest in the United States?

PHILONOUS That is likely one of the reasons but definitely not the only one. The problem of mental illness is just another aspect of the complex dynamics of social systems. It is fashionable for the affluent in North America to have “issues” with their subconscious and a psychoanalyst to deal with them. But this trend is more than a form of snobbery. There is no doubt that mental life, along with its realm of subconscious, can be cast in many different molds, and its manifestations can be interpreted in many different ways. When such conventions spread through a given environment, as in the United States, a majority of well-to-do people will eventually turn into a willing and welcome material for psychoanalysts. Such people produce dreams in accordance with Freudian theory and exhibit textbook “complexes,” thereby verifying the tenets of psychoanalysis (including those that are doubtful) as the pansexualism of the subconscious, the prevalence of the Oedipus complex, and the fear of castration. Attempts to find a comparable epidemic spread in subconscious mental life in a society with different conventions, say, in a centralist system, would be fruitless. Thus the phenomena proclaimed by psychoanalytic theory constitute a closed circuit with positive feedback: patients fuel the psychoanalysts’ faith in the validity of their theses, and the psychoanalysts in turn amplify the beliefs and symptoms in their patients. But it is not true that everyone’s subconscious is populated by sexual symbols to be uncovered by a psychoanalyst; in reality, these phenomena are relatively rare and found only in a precisely defined environment (people who are well-to-do and fairly intelligent, or at least who believe they are such). Yet they can impose themselves on and spread through larger segments of a population, which then creates the impression of their universal prevalence.

In reality this is just a part of a much broader phenomenon—the imposition of specific conventions on society. The psychoanalytic convention is better than the medieval convention of witch-hunting, but only because it harms no one except the patient. In general, if one undertakes to impose a certain norm, convention, or way of life on a given society and does it with sufficient resolve and ruthlessness, the desired effect will be always achieved: the stratification of a previously homogeneous group, say, or the emergence of a new antagonism to cover up an antagonism more fundamental in that it comes not from propaganda, an irrational taboo, or an obsolete doctrine but from an objective perturbation in the dynamics of the social structure. The well-known ancient method of divide et impera is precisely such a use of imposition.

Bearing in mind the example of the horrible sociological experiments that were the Nazi concentration camps, we can conclude that through the use of coercion with no limits one can construct almost any system of interpersonal relations and impose on it any preselected stratification or segregation into privileged and disadvantaged sections or into a hierarchically ordered castes, where the only real benefit of being an “elite” may be a short delay in death at an executioner’s hands. I am referring, of course, to what took place in the ghettoes during the Occupation. That phenomenon no doubt deserves careful sociological analysis.4

HYLAS I have to admit that these new aspects of the problems of coexistence in human society (particularly regarding conventions that can steer people’s minds and selection criteria in a given system) have muddled the picture that I formed during our conversation up to this point. I mean the model of society as seen by cybernetics. I don’t see how, or if, we can include into it the things that we are discussing.

PHILONOUS I am not claiming that cybernetics is methodologically omnipotent because I have no wish to replace one generalization with another. Yet where is the difficulty here? All the phenomena that we have discussed can be interpreted as, on the one hand, instances of mental processes in certain neural networks and as, on the other hand, the transmission of information in the vast network that is a society. An adequately developed mathematical apparatus of information theory will be rich enough to model all this.

Let me summarize what we have established in our discussion of structures of social systems—from the perspective of cybernetic sociology, which is yet to emerge. Any activity that is taking place in a social system under coercion or repression has basically a single aim, to turn a nonlinear system into a linear one by the simplest means, namely, by decreasing the number of degrees of freedom available to the individuals who are the system’s elements. Imposing on these elements prescribed norms of behavior (which should be as uniform as possible), and thus erasing the diversity in all individual responses, makes it easier to predict, regulate, and shape the future course of social processes.

Conversely, the more freedom the individuals are given, the greater the nonlinear perturbations in social processes, because the range of possible actions will broaden, contradictory opinions will appear, and there will be debates and opposing actions. As the system moves further and further from linearity, maintaining its internal cohesion and predicting its future will become more and more difficult.

Although it is easier to maintain order and keep all the processes of a system on a smooth course when force is used, and although people can adapt to living according to the norms and conventions imposed on them, data obtained from history as well as from studies and experiments in the last few decades clearly show that the mechanical effectiveness of a system and its linear character alone do not guarantee that its elements, people, will be happy.

HYLAS So we must seek a golden mean between linear and nonlinear, between the maximum freedom of anarchy, which dismantles any structure in society, and the other extreme, the shackles of uniformity?

PHILONOUS In a sense. I am just rephrasing what we already said about the necessity of bringing into one system the highest possible degree of individual freedom and the highest possible degree of internal cohesion based on the mutual complementarity of human traits.

HYLAS I confess that I have grown pessimistic about the prospects of creating a mathematized sociology, understood as a general dynamic theory of social systems, because I can see all the trouble piling up on that path. You said yourself that a person’s behavior, or, if you prefer, future operations and states of his neuronal network are not completely determined by its past states, and therefore predicting future states of a social system, no matter how deeply rooted the prediction is in a theory that is most mathematical of all, will only amount to listing a series of possibilities with varying degrees of probability. Talking about a “design” or “structure” when conditions are so fluid and developmental options so numerous—is that not groundless cognitive optimism? If we subjected a system of tyranny to a rigorous analysis, our cybernetic model would have to incorporate not only the fact that some information was blocked while misinformation was being spread in the society’s information channels, but it would also have to factor in such psychological responses to tyranny as individuals’ fear or cunning and—what would be the most difficult—it should contain the possibility of the emergence of an exceptional individual (say, a Marx) who would organize a theory-based freedom movement. What mathematical model can account for such a possibility? How to calculate the probability of its realization? I just cannot envision it.

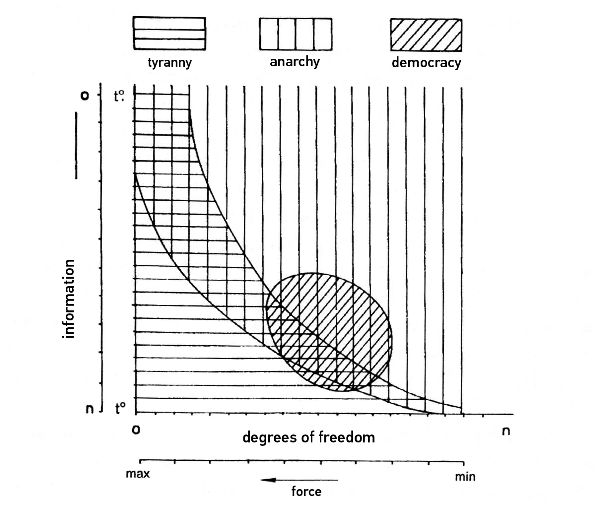

PHILONOUS These are not insurmountable difficulties. Let me give you a simple example of a rigorous, mathematical treatment of a sociological problem. Take three possible aggregate phases of social “atoms,” that is, of people: tyranny, democracy, and anarchy. The imprecision of these terms, at the present state of our knowledge, is unavoidable. The x-axis indicates the number of the degrees of freedom possessed by individuals. Zero degrees of freedom would mean that a person is incapable of any action, that is, he is dead. Someone whose behavior is not constrained by the existence of others and who does not take into account anyone besides himself has an infinite number of degrees of freedom—Robinson Crusoe might be an example of that. We should, of course, distinguish degrees of freedom with respect to other people and those with respect to physical environment (including a civilizational level), but we will neglect this here for simplicity. The second scale under the x-axis is a measure of the force acting on the system: at the maximum, the smallest transgression of the existing norms and laws is punishable by death; at the minimum, there is no punishment for anything. Evidently, the stronger the acting force, the fewer the degrees of freedom. On the y-axis we have the “mental temperature,” which is the tendency to act spontaneously, regardless of or even despite the existing laws, norms, and conventions (either imposed or voluntarily accepted) in the system. The second scale on the y-axis shows the amount of information that activates spontaneous action at the given “mental temperature” in the community.

The graph shows the three partially overlapping regions of tyranny, anarchy, and democracy. The lines that define the phases represent phase boundaries; crossing them signifies a transition from one phase to another.

Where the phases overlap, two or even all three systems can coexist at the given values of the parameters, but of course only as alternatives in any given society at the given time. In the single-shaded regions there is absolute sociodynamic stability of the phase. The overlapping areas represent parameter values at which each of the phases has relative stability, with a specific (statistically determined) probability of transition to another phase. The graph, though simple and primitive, provides insight. Observe first that with few degrees of freedom, corresponding to a significant external force, the only stable phase at a low “mental temperature” is tyranny. As the number of degrees of freedom increases while the “mental temperature” stays low, we reach a critical point in tyranny’s relative stability; the probability of a revolution increases, until, above a particular value of the number of degrees of freedom, it becomes a certainty—but the phase that replaces it can only be anarchy. If the degrees of freedom increase at a higher “mental temperature,” we reach the region in which the transition may be to anarchy but also to democracy. Whereas both tyranny and anarchy have regions of absolute stability, democracy does not, which means that there are no parameter values at which the transition of either anarchy or tyranny to democracy would be a certainty from the point of view of sociodynamic probability. Above the critical value of “mental temperature,” anarchy becomes the only possibility, because such a community will not be subject to any conventions, whether democratic or autocratic, that would organize the group of human atoms into a structure (governed or self-governed). Finally, there can be such a high number of degrees of freedom that only anarchy can exist, this time simply because there are no laws or conventions to regulate the behavior of individuals.

What else can we deduce from our graph? First, it implies that as long as a tyrant keeps the communal “mental temperature” below the critical point and at the same time does not allow the number of degrees of freedom to increase (i.e., the tyrant will use whatever force is needed), the tyranny phase can exist indefinitely, at least in theory. Second, democracy is a sociodynamic phase that is only relatively stable: an increase in either the mental temperature or the degrees of freedom above an optimal value will increase the probability of its transition to anarchy, and a decrease in these factors will lead to tyranny. Third, at a very low or very high mental temperature tyranny cannot transition to democracy; if there is any transition, it will be directly to anarchy.

Of course, all this is well known from history, both ancient and modern. What is novel is the use of an analogy from physical chemistry, more specifically from the theory of thermodynamic equilibrium between phases. Just as water can exist in the liquid phase above its boiling point only under elevated pressure, tyranny can exist above a particular mental temperature only under the elevated “pressure” of repression. And, just as there exists a value of high temperature (the critical point) above which no pressure can liquefy water, if the mental temperature becomes very high (e.g., when the oppressed feel they have nothing more to lose), even the use of maximum force cannot prevent the transition from tyranny to anarchy.

The graph even answers your question about the possibility of predicting the emergence of a Marx in a given society: the possibility is equivalent to that of the emergence of an unusually large amount of “triggering information” from spontaneous nonconformist activities. At a low mental temperature, the amount of information required to trigger a community may unfortunately be close to infinite. The graph indicates that change is possible only in regions whose stability or equilibrium is not absolute. In addition to the sociodynamic probability of a change (not depicted), we need to consider “socio-energetics.” The overthrow of a social structure requires human effort. At the same temperature and freedom, it is generally easier to overthrow democracy and install tyranny than the other way around. The installation of anarchy requires the least effort. The transition from anarchy to democracy requires energy, but the transition from tyranny to anarchy may occur spontaneously (similarly from democracy to anarchy), because in that case all structure is being liquidated—an example: when a tyrant dies and his henchmen flee, chaos results.

HYLAS How can there be anarchy with a low number of degrees of freedom?

PHILONOUS That happens only at very high temperatures, where it is not the power of the government (there is no government) that limits an individual’s action but the impulsiveness and expansiveness of other individuals (which will be enormous at such a high mental temperature). In terms of sociological consequences, do not take the upper part of the graph too seriously. Without any participation of social structure, mental temperature values can develop a pressure that lowers the number of degrees of freedom—for example, during a volcano eruption, on a sinking passenger ship, or in a city engulfed in urban warfare. In normal circumstances a community does not reach such temperatures, although individuals can. But let us return from our excursion to sociology’s past into the present.

HYLAS One more question, Philonous. It seems to me that the graph should also contain empty, nonshaded areas, in which no phase of social aggregation is possible. If the universal “boiling” of minds rules out a large number of degrees of freedom, as you just said, then a state that cannot occur should be called “forbidden”—by analogy to similar physical states (in quantum mechanics).

PHILONOUS I see your point. States that you call “forbidden” would be those with an extremely low sociodynamic probability of occurring. This probability fundamentally depends on the community’s history, which causes the nonlinear functional dependence of both our parameters in the first place. A sudden increase of freedom in tyranny (after the government’s retreat and a release from repression) usually results in an increase in mental temperature and demands for more freedom; the government then either gives in or returns to repression. So we have here a rather complicated dependence with cyclical feedback loops (an increase in repression activates negative feedback, whereas decreased repression activates positive feedback, that is, enhances community demands). Yet sometimes this process may unfold differently, and the government’s retreat fails to increase the mental temperature. What is then the functional dependence between the two parameters? Think of an animal in a cage. When we open the cage and free the animal, we grant it a greater number of degrees of freedom. But sometimes the animal, released, will continue behaving as if it were still in the cage, pacing just a few steps back and forth, because its lifelong behavioral conditioning is stronger than the new situation. A society that has been living under tyranny for a long time, especially a ruthless tyranny, may not exhibit a rise in mental temperature after the government retreats and prohibitions are removed. The people may not behave in a wild and nonconformist way. But as the government continues to weaken and a social cohesion that it imposed drops, for any reason, almost to zero, the society, being at the border of the tyranny’s instability, can “explode” and transition to total anarchy in a single jump in mental temperature. Another society, having a history free of repression, will react in a completely different way to both the repression and its weakening. Hence the nonlinearity of a social system stems from the system’s history and experience. Without taking history into account, our graph has no prognostic value, and I never claimed that it had any. To calculate the sociodynamic probability of a transition requires taking into account additional parameters, which is precisely the task for the future theory. Even the terms like “tyranny” and “anarchy” as signifiers of phases of social aggregation are just simplifying generalizations of many structural possibilities. Furthermore, in addition to mass-statistical aspects, the theory will have to take into account also individual aspects of these phenomena. As you know, a speck of dust dropped into water will not affect its state, but if the water is supercooled below the freezing point, the speck, acting as a crystallization nucleus, will cause a sudden change of water into ice. Similarly, an individual’s role in the shaping of social processes or the reorganization of an existing structure depends on that structure. When a tyranny is absolutely stable, even the most nonconformist element will accomplish nothing except its personal liquidation. But if the stability is only relative and the number of degrees of freedom is high enough, the same element can precipitate an uprising. This too is a simplification because we neglected a society’s class stratification, which also plays a role here. But enough of divagations, let us return to our topic.

HYLAS Why, when we seem to be on the verge of making some interesting conclusions? The role of an individual in social transitions surely deserves attention. Continuing your physicochemical analogy, I would call your approach catalytic. You say that an individual can significantly affect the course of history when the “potential for nonconformist activity” exists and the present state of the given community allows for it. The push he gives then to the social processes is like the bit of a catalyst that makes possible a chemical reaction. The given individual possesses special abilities, those of a catalyst. But imagine a situation when any individual, without any special skills, can affect the course of social transformations, namely, when he occupies a privileged position in the social structure. A king or tyrant can be a completely mediocre person but because all feedbacks in social processes converge in him, he has the power to make decisions on war or peace, and other important issues. Therefore, the “catalytic” effect of an individual on a society can take place only when the state of the system and the qualities of the individual are right, though “topology,” that is, the position that the individual occupies in the structure, is also relevant.

PHILONOUS Indeed, an individual can affect the fate of a society like this only in certain systems. An ideal system would make the “topological” and “catalytic” factors, as you call them, independent of each other. A society’s fate cannot, and should not, depend on whether its leaders are “providential” or mediocre. Social engineering would not be possible if every construction depended on the chance appearance of exceptional people. The maximum degree of freedom in such an “ideal” system must not include the freedom of putting society’s fate into the hands of one person. The maximum values of parameters (e.g., number of degrees of freedom) in a social system do not equal to the optimum values that ensure the stability of its structure and processes. Hylas, we could talk about this for hours. Let us instead return to our topic.

HYLAS I won’t allow that. Your refusal to admit the influence of exceptional individuals in a society is no different from prohibiting any deviation from linearity, and therefore it amounts to limiting the degrees of freedom in order to preserve the system’s structure. How is this better, I ask, than what a tyrant does?

PHILONOUS But, Hylas, if we construct an optimal system, we must protect it from disintegration or turning into a system that is worse (e.g., one that oscillates). The whole point is to embed this protection into specific automatic social processes instead of using force! Once a system’s construction begins to be based on a scientific theory, there is no longer any place for human whim or multiparty politicking. Imagine the construction of an atomic reactor that is not carried out according to a unified plan based on the theory of physics but instead depends on competing “programs” thought up ad hoc by individual physicists. It will end either in a disaster or in nothing. Similarly, once we have determined that the best way to prevent polio is by vaccination, we must prevent charlatans from replacing the vaccine with “healing beads” and other nostrums. From the viewpoint of scientific sociology, politicians are amateur healers of social ills, practitioners who, lacking theoretical knowledge, are guided by intuition—at best. If, having recognized the role that science plays in all areas of life, we prohibit it from articulating rules that would be binding for everyone in the realm of social relations, then we will regress to the time before Marx, my friend! When an astronomer says that the Sun is 150 million kilometers from the Earth, is he “imposing” this on people? Your objections are methodological nonsense and serve only to show the enormity of the irrational resistance that needs to be overcome in people so that they will accept the objective sociological laws and everything that follows from them.

HYLAS You argue that no statistical fluctuation in activity caused by an individual should be allowed to make a dynamically stable structure unstable. But as an astronomical theory must hold for as long a period as possible, so must a sociological theory. If we look into the abyss of future time that gapes before humanity, we must conclude that the current bases of both individual and collective action, rooted in the economy, will atrophy and disappear someday. Automated manufacturing, atomic energy, and their synthesis will provide people with a practically unlimited amount of goods. What then? New forms and contents of human activity, which will go beyond the economic—because when all needs are satisfied, economic stimuli are unnecessary—will unavoidably change social structure. And since no theory can foresee the psychological contents and the cultural and civilizational conventions that will exist after we become free of the economic motivation of behavior, we must accept that neither can the theory of social engineering do that. According to this theory, our “ideal” system will be only one of many stages on the path that leads to a society whose tasks and goals we cannot even imagine.

PHILONOUS You are putting in different words what I have already said: no system of interpersonal relations can be eternal. An astronomical theory holds for billions of years; a sociological one, for perhaps a few centuries—precisely because society is a nonlinear system. Yet, although we cannot predict all social processes and states, our theory is not as weak as you think: it can entertain the possibilities. Although we do not know what collective human activities will be like ten thousand years from now, we do know that, given the relatively slow rate of biological evolution of species, the neural network of a human being will not undergo any fundamental reorganization in that time. Because society will consist of people very similar to us, we should be able, with the help of the general theory of sociology, if not to envision the contents of life in the future, then at least its possible forms, its possible structures, for the simple reason that it is the structure of human neural networks that affects social dynamics and determines the teleological, evaluative, symbolic, and self-preserving activities of the humans. The content of symbols, goals, and values of the future may differ as much from ours as ours differ from those of the Neanderthals, but the fundamental laws of the behavior of neural networks remain essentially the same. A social system whose members follow those laws—regardless of the motivational, economic, or meta-economic specifics of their activity—must exhibit universal regularities that a theory can articulate.

Here is an example of how partial freedom from economic motivation may affect behavior. In societies with the highest levels of well-being, there appears the paradoxical phenomenon of rebellion “without a cause,” in which groups of young people attempt to destroy the existing order and values purely for the sake of destruction. No other reason can be found. These youths are free of concern about their existence; they do not need to struggle for a career or livelihood. From the economic point of view, their behavior is irrational. But our theory predicts this, based on the general characteristics of human neural networks, as a manifestation of active teleological behavior and creative valuation when the economic motivation for action is weakened. In a society with a sufficient level of well-being and established general order, an individual who longs for a goal not preset by social conventions and seeks new values (most often it is young people who do this) must possess certain intellectual abilities. Without them the individual is unable to join the ranks of those who create new material and spiritual goods and can therefore externalize this desire only by opposing what exists. I am simplifying, of course, and a psychological analysis of these occurrences might explain more—but in our theory, which is by nature statistical, that explanation would be irrelevant. My point is that it will be possible to analyze such general regularities by formal, mathematical means—through studying the dynamic osculation, or the absence of it, between the individual processes in the network and the overall processes in the system.5 Since the number of formal processes (or the number of possible variants in connectivity and excitatory/inhibitory influences) in a neural network is incomparably smaller than the number of the contents variants in those processes and since the number of possible, and stable, social structures is likewise smaller than the number of all processes that can possibly take place in them, solving this task should not be as difficult as one might expect based on traditional psychology or the traditional treatment of the relation between an individual and society. Now, perhaps, you will finally allow me to return to the topic, which is, frankly, more modest than these exalting but unavoidably too general divagations.

HYLAS All right, but only after I say what I have to say. I think I understand what you want to convey. The desires, hopes, drives, fears, and pleasures of an individual enter this world without clothing and without direction. It is only the existing reality that gives them shape, form, direction, and a plan for action; brings to life all the forces of the human soul, which do not know themselves; and gives them names and meanings by incorporating them in the order of social structure. I can imagine the language, taken from triumphant physics, of the future theory: the social continuum, probabilities, potentials of sociodynamic transformation, predictions based on statistics, and the deindividualized, mass nature of those transformations. Just as the physical state of a cloud of atoms with various velocities is determined by external conditions—the walls of its container and the pressure exerted by a piston—and just as the action of those atoms depends on the shape of the channel into which they are funneled—so that they move a turbine or expand while cooling or crystallize into ice under pressure—the social atoms subjected to various mental temperatures and pressures will do work that is determined by the dynamic structure of their ensemble, which is, in turn, predetermined by sociological engineers. All possible variants must be considered so that the parameters do not “misbehave,” so that any possibility of initiating a chain reaction that could destroy the structure or form dangerous local condensations or dilutions is ruled out, as is the possibility that the “atoms” in the absence of a regulating channel use their natural energy for nonconstructive acts of destruction without any rational incentives or justifications. I understand the necessity of such foresight and action and applaud the resolve to avoid the use of force by replacing it with the very links that connect the self-organizing social atoms and whose objective emergence under any given conditions and parameter values can be predicted by a mathematical theory, in which energy that is exchanged and transported in collisions between gas molecules will be replaced in the social system with information charges that propagate from one individual to another.

I see the inevitability of this, but why, instead of celebrating this future triumph of human beings over themselves, do I feel anxiety? Excuse my weakness, Philonous, for solitary lyrical ponderings under the stars. I think of Dostoevsky and his words from Notes from Underground: “There will someday be discovered the laws of our so-called free will—so, joking aside, there may one day be something like a table constructed of them, so that we really shall choose in accordance with it. . . . You tell me again that an enlightened and developed man, such, in short, as the future man will be, cannot consciously desire anything disadvantageous to himself, that this can be proved mathematically. I thoroughly agree, it can—by mathematics. But I repeat for the hundredth time, there is one case, one only, when man may consciously, purposely, desire what is injurious to himself, what is stupid, very stupid—simply in order to have the right to desire for himself even what is very stupid and not to be bound by an obligation to desire only what is sensible. . . . It is just his fantastic dreams, his vulgar folly that he will desire to retain, simply in order to prove to himself—as though that were so necessary—that men still are men and not the keys of a piano, which the laws of nature threaten to control so completely that soon one will be able to desire nothing but by the calendar. . . . If you say that all this, too, can be calculated and tabulated—chaos and darkness and curses, so that the mere possibility of calculating it all beforehand would stop it all, and reason would reassert itself, then man would purposely go mad in order to be rid of reason and gain his point!”6 If Dostoevsky is right, then what of your sociodynamic theory of the golden age, Philonous?

PHILONOUS Yes, he is right, and this truth can be—oh, paradox—expressed in mathematical terms, as a prediction of the constant appearance in a community of nonconformist individuals, both positive (creators of values) and negative (destroyers of values). But what exactly is Dostoevsky opposing so forcefully? The predictability of human actions, if I understand correctly. Yet a precise, deterministic predictability of human behavior is a fiction. We can calculate probabilities, not predict specific actions; if someone acted in certain way just to defy the “psychological forecast,” he would only have my sympathy. Nevertheless, I suspect that your point is not this but the “crystal palace” of the future society, as Dostoevsky called it, or the “ideal system,” as we did. As for life in this “palace,” it does not mean uniformity or equalization—on the contrary! The dependence of one individual on others, which is inescapable in any social structure, can indeed lead to harmful stratification, to the exclusion of some groups and the elevation of others. But we can also set up such a distribution of fields of individual activity that, if we focus just on two people, person 1 will be subordinate to person 2 in domain A, while in domain B person 2 will be subordinate to person 1. This way, a relative equilibrium between dominance and submission would establish itself and be distributed evenly throughout the dynamic structure of interpersonal relations, which would prevent the emergence of any harmful automatic mechanisms of hierarchical stratification of society.

Such stratification arises not only from direct relations between two or more people, which we might call “short links,” but also from the “long links,” which represent institutional assemblies that disturb the homogeneity of the ensemble. The latter type of links set themselves apart by profession, for example. Economically determined relations, such as ownership versus lack of ownership of the means of production, also are “long links.” To strike the right balance between the segregating and stratifying tendencies of the long vs. short links is the touchstone of any theory of sociological engineering and at the same time its most difficult challenge. If we do not wish (and we do not indeed!) to stabilize the ideal structure by force, which would lead to uniformity and a reduction in complexity, then we have no choice but to make the interpersonal relations and the whole structure more complex, of course, not just randomly but according to the theory’s guidelines. In a structure that is dynamically stabilized by the overall formal complexity, no segregation (based on dominance-submission relations, on mental or physical traits, etc.) will emerge and a greater variety of options will open for an individual than in any structure known in the history. There is no reason here to worry about social determinism. But the issue of “limiting the moral costs” of social experimentation, without which any future progress will be impossible, is important. So all that remains of Dostoevsky’s argument is a deep-rooted opposition to any kind of social modeling or engineering as a matter of principle. Which amounts to a surrender to the spontaneous and blind mechanism of the existing laws and a passive acceptance of all their harmful consequences—for they exist whether we like it or not. By analogy one might feel disgust for any sort of “artificial” treatment of a disease, advocating instead a reliance on the “natural powers” of the human body. The consequences would be most unfortunate. All the evils that humankind has ever suffered, and is still suffering today, as a consequence of our being an animal sociale, were caused by a lack of knowledge or by knowledge applied imperfectly or incorrectly, but never by too much knowledge. With this, I would like to conclude the argument about these imponderabilia, generalized to the highest possible degree.

We were talking about psychometrics. For the future sociologist-engineer it will be a helping tool only, never a recipe for an action, because which positions need to be filled, which professions and functions are socially in demand, what the organizational plan for production and distribution should look like—all this is determined not by psychometrics but by social structure (plus the level of civilization). Psychometrics, like material science in engineering, can tell us with what (or more properly, with whom) to fill the vacant spots in the construct, but the construct, the blueprint, must already exist.

Let us now return to our point of departure, that is, to the importance of intelligence and the role of intellectuals in a society, about which we can say the following: the future path of humanity’s development does depend to a large extent on intellectuals, people with higher mental abilities than the rest, but the cohesive functioning of the social machine, without which a society here and now cannot exist and therefore evolve, is determined mainly by the noncreative—or, better, less creative—work of the majority of people who are average; this way mental skills and abilities of all members of society complement each other. Psychometrics, as a differentiating measuring tool, should only serve one purpose, to make sure that the right people are directed to the right positions in the system; under no circumstances should it turn into a tool for hierarchization, which introduces elitism, social inequality, and privilege.

Please note that the creation of thinking machines introduces a new kind of equality, because there is no longer any human activity that in principle cannot be performed by a machine. Not that long ago people thought that only “lower” activities, such as physical labor, were subject to mechanization, that mental work could never be. Now the line between mental and physical labor is disappearing, which means that the tendency of intellectuals to consider themselves the most valuable members of society must soon disappear as well.

HYLAS It really wasn’t my intention to pit intellectuals against physical laborers. I was only protesting against stupidity. We can safely assume that there are stupid shoemakers, but there are stupid intellectuals as well, who can actually cause more harm than the stupid shoemakers.

PHILONOUS Even the stupid should not be judged hastily and denied their right to coexist with other people, for we all must live on the same planet. Any attempt to wipe out stupidity as a social phenomenon inevitably leads to societal stratification, until the day arrives when we acquire the means for the biological transformation of our species. In every society there are people on the low side of the normal Gaussian distribution curve of intelligence, and they are an integral part of society. To isolate them, whether intentionally or not, will only lead to additional stratification, which, just like the stratifications by race or class in the past, cannot bring humanity anything but suffering and war. Not even our ideal system can make incompetent people competent, and to expect that of any sociological construct would be a dangerous utopia out of touch with the real world. People who differ from one another in personality, mental speed, character, and intelligence—in short, all people—must coexist within the same social system. Because they differ, their suitability for various occupations will also differ. It will be the task of psychometrics to point them to paths that give them the most satisfaction from their activity and at the same time ensure the optimal fulfillment of society’s needs; the selection should have nothing to do with an evaluative stratification of society.7

Apart from the stratification resulting from evaluative differentiation based on mental (intelligence, character) or physical (race) traits and apart from the traditional segregation based on birth, pedigree, and so on, there is the danger of stratification according to economic factors (the main subject of Marx’s theory). In the highly developed societies of the future there is also the possibility of quasi-caste segregation due to professional and scientific overspecialization.

Predicting and combating these phenomena is the first duty of the engineer-sociologist. Because a society must be cohesive, we cannot be too careful in our projecting and constructing it. As we are well aware, those put in charge of the feedback between the government and the economy tend to elitistically monopolize their function, particularly if it is supported by a centralist feedback system. It is true that harmful tendencies toward stratification, division, and eventually antagonism between groups and their interests, which are sources of conflicts, appear in all kinds of systems. But it is also true that our ability to experiment, search, and choose in this area is limitless. Despite all the disappointments, defeats, and tragic mistakes of the past, people will build a better world. Should we act without this principle in mind, we would lose faith in humanity and its potential, and in that case, my friend, it would be better not to live.

Kraków, 1954/1955–December 1956