WHEN the first bitterness was over, the family accepted the inevitable, and tried to bear it cheerfully, helping one another by the increased affection which comes to bind households tenderly together in times of trouble. They put away their grief, and each did their part toward making that last year a happy one.

The pleasantest room1 in the house was set apart for Beth, and in it was gathered everything that she most loved—flowers, pictures, her piano, the little work-table, and the beloved pussies. Father’s best books found their way there, mother’s easy chair, Jo’s desk, Amy’s loveliest sketches; and every day Meg brought her babies on a loving pilgrimage, to make sunshine for Aunty Beth. John quietly set apart a little sum, that he might enjoy the pleasure of keeping the invalid supplied with the fruit she loved and longed for; old Hannah never wearied of concocting dainty dishes to tempt a capricious appetite, dropping tears as she worked; and, from across the sea, came little gifts and cheerful letters, seeming to bring breaths of warmth and fragrance from lands that know no winter.2

Here, cherished like a household saint in its shrine, sat Beth, tranquil and busy as ever; for nothing could change the sweet, unselfish nature; and even while preparing to leave life, she tried to make it happier for those who should remain behind. The feeble fingers were never idle, and one of her pleasures was to make little things for the school children daily passing to and fro. To drop a pair of mittens from her window for a pair of purple hands, a needle-book for some small mother of many dolls, pen-wipers for young penmen toiling through forests of pot-hooks,3 scrap-books for picture-loving eyes, and all manner of pleasant devices, till the reluctant climbers up the ladder of learning found their way strewn with flowers, as it were, and came to regard the gentle giver as a sort of fairy god-mother, who sat above there, and showered down gifts miraculously suited to their tastes and needs. If Beth had wanted any reward, she found it in the bright little faces always turned up to her window, with nods and smiles, and the droll little letters which came to her, full of blots and gratitude.4

The first few months were very happy ones,5 and Beth often used to look round, and say “How beautiful this is,” as they all sat together in her sunny room, the babies kicking and crowing on the floor, mother and sisters working near, and father reading in his pleasant voice, from the wise old books, which seemed rich in good and comfortable words, as applicable now as when written centuries ago—a little chapel, where a paternal priest taught his flock the hard lessons all must learn, trying to show them that hope can comfort love, and faith make resignation possible. Simple sermons, that went straight to the souls of those who listened; for the father’s heart was in the minister’s religion, and the frequent falter in the voice gave a double eloquence to the words he spoke or read.

It was well for all that this peaceful time was given them as preparation for the sad hours to come; for, by and by, Beth said the needle was “so heavy,” and put it down forever;6 talking wearied her, faces troubled her, pain claimed her for its own, and her tranquil spirit was sorrowfully perturbed by the ills that vexed her feeble flesh. Ah me! such heavy days, such long, long nights, such aching hearts and imploring prayers, when those who loved her best were forced to see the thin hands stretched out to them beseechingly, to hear the bitter cry, “Help me, help me!” and to feel that there was no help.7 A sad eclipse of the serene soul, a sharp struggle of the young life with death; but both were mercifully brief, and then, the natural rebellion over, the old peace returned more beautiful than ever. With the wreck of her frail body, Beth’s soul grew strong; and, though she said little, those about her felt that she was ready, saw that the first pilgrim called was likewise the fittest, and waited with her on the shore, trying to see the Shining Ones8 coming to receive her when she crossed the river.

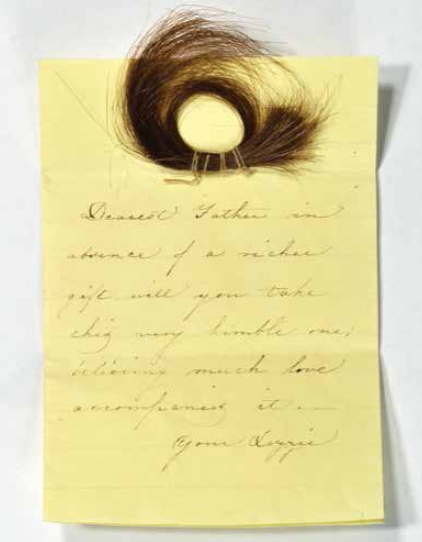

Lizzie Alcott’s sewing kit was a gift from her father. As her final illness worsened, she found the needle too heavy to lift. (Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

Jo never left her for an hour since Beth had said, “I feel stronger when you are here.”9 She slept on a couch in the room, waking often to renew the fire, to feed, lift, or wait upon the patient creature who seldom asked for anything, and “tried not to be a trouble.” All day she haunted the room, jealous of any other nurse, and prouder of being chosen then than of any honor her life ever brought her. Precious and helpful hours to Jo, for now her heart received the teaching that it needed; lessons in patience were so sweetly taught her, that she could not fail to learn them; charity for all, the lovely spirit that can forgive and truly forget unkindness, the loyalty to duty that makes the hardest easy, and the sincere faith that fears nothing, but trusts undoubtingly.

Often when she woke, Jo found Beth reading in her well-worn little book, heard her singing softly, to beguile the sleepless night, or saw her lean her face upon her hands, while slow tears dropped through the transparent fingers; and Jo would lie watching her, with thoughts too deep for tears, feeling that Beth, in her simple, unselfish way, was trying to wean herself from the dear old life, and fit herself for the life to come, by sacred words of comfort, quiet prayers, and the music she loved so well.

Seeing this did more for Jo than the wisest sermons, the saintliest hymns, the most fervent prayers that any voice could utter; for, with eyes made clear by many tears, and a heart softened by the tenderest sorrow, she recognized the beauty of her sister’s life—uneventful, unambitious, yet full of the genuine virtues which “smell sweet, and blossom in the dust”;10 the self-forgetfulness that makes the humblest on earth remembered soonest in heaven, the true success which is possible to all.

One night, when Beth looked among the books upon her table, to find something to make her forget the mortal weariness that was almost as hard to bear as pain, as she turned the leaves of her old favorite Pilgrim’s Progress, she found a little paper scribbled over, in Jo’s hand. The name caught her eye, and the blurred look of the lines made her sure that tears had fallen on it.

“Poor Jo, she’s fast asleep, so I won’t wake her to ask leave; she shows me all her things, and I don’t think she’ll mind if I look at this,” thought Beth, with a glance at her sister, who lay on the rug, with the tongs beside her, ready to wake up the minute the log fell apart.

“MY BETH.

“Sitting patient in the shadow

Till the blessed light shall come,

A serene and saintly presence

Sanctifies our troubled home.

Earthly joys, and hopes, and sorrows,

Break like ripples on the strand

Of the deep and solemn river

Where her willing feet now stand.

“Oh, my sister, passing from me,

Out of human care and strife,

Leave me, as a gift, those virtues

Which have beautified your life.

Dear, bequeath me that great patience

Which has power to sustain

A cheerful, uncomplaining spirit

In its prison-house of pain.

“Give me, for I need it sorely,

Of that courage, wise and sweet,

Which has made the path of duty

Green beneath your willing feet.

Give me that unselfish nature,

That with charity divine

Can pardon wrong for love’s dear sake—

Meek heart, forgive me mine!

“Thus our parting daily loseth

Something of its bitter pain,

And while learning this hard lesson,

My great loss becomes my gain.

For the touch of grief will render

My wild nature more serene,

Give to life new aspirations—

A new trust in the unseen.

“Henceforth, safe across the river,

I shall see forever more

A beloved, household spirit

Waiting for me on the shore.

Hope and faith, born of my sorrow,

Guardian angels shall become,

And the sister gone before me,

By their hands shall lead me home.”11

Blurred and blotted, faulty and feeble as the lines were, they brought a look of inexpressible comfort to Beth’s face, for her one regret had been that she had done so little; and this seemed to assure her that her life had not been useless—that her death would not bring the despair she feared. As she sat with the paper folded between her hands, the charred log fell asunder. Jo started up, revived the blaze, and crept to the bedside, hoping Beth slept.

“Not asleep, but so happy, dear. See, I found this and read it; I knew you wouldn’t care. Have I been all that to you, Jo?” she asked, with wistful, humble earnestness.

“Oh, Beth, so much, so much!” and Jo’s head went down upon the pillow, beside her sister’s.

“Then I don’t feel as if I’d wasted my life. I’m not so good as you make me, but I have tried to do right; and now, when it’s too late to begin even to do better, it’s such a comfort to know that some one loves me so much, and feels as if I’d helped her.”

“More than any one in the world, Beth. I used to think I couldn’t let you go; but I’m learning to feel that I don’t lose you; that you’ll be more to me than ever, and death can’t part us, though it seems to.”

“I know it cannot, and I don’t fear it any longer, for I’m sure I shall be your Beth still, to love and help you more than ever. You must take my place, Jo, and be everything to father and mother when I’m gone. They will turn to you—don’t fail them; and if it’s hard to work alone, remember that I don’t forget you, and that you’ll be happier in doing that, than writing splendid books, or seeing all the world; for love is the only thing that we can carry with us when we go, and it makes the end so easy.”

“I’ll try, Beth;” and then and there Jo renounced her old ambition, pledged herself to a new and better one, acknowledging the poverty of other desires, and feeling the blessed solace of a belief in the immortality of love.

So the spring days came and went, the sky grew clearer, the earth greener, the flowers were up fair and early, and the birds came back in time to say good-by to Beth, who, like a tired but trustful child, clung to the hands that had led her all her life,12 as father and mother guided her tenderly through the valley of the shadow, and gave her up to God.

Seldom, except in books, do the dying utter memorable words, see visions, or depart with beatified countenances; and those who have sped many parting souls know, that to most the end comes as naturally and simply as sleep. As Beth had hoped, the “tide went out easily”; and in the dark hour before the dawn, on the bosom where she had drawn her first breath, she quietly drew her last, with no farewell but one loving look and a little sigh.13

With tears, and prayers, and tender hands, mother and sisters made her ready for the long sleep that pain would never mar again—seeing with grateful eyes the beautiful serenity that soon replaced the pathetic patience that had wrung their hearts so long, and feeling with reverent joy, that to their darling death was a benignant angel—not a phantom full of dread.

1. The pleasantest room. During Lizzie Alcott’s last months, her family also made things as pleasant as possible for her, though they were not as quickly resigned to fate as were the Marches. Louisa wrote in her journal for October 1857, “Fit up a nice room for her, and hope home and love and care may keep her” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 85).

2. know no winter. In January 1858, Lizzie’s doctor pronounced her case hopeless, and the Alcotts came together to give her the best care they could. Alcott wrote, “Father came home; and Anna took the housekeeping, so that Mother and I could devote ourselves to her” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 88).

3. pot-hooks. The name given to the looping strokes that children were taught to make when learning to write.

4. full of blots and gratitude. Like Beth, Lizzie Alcott spent many of her last days trying to benefit others: “Lizzie makes little things, and drops them out of windows to the school-children, smiling to see their surprise. . . . Dear little saint! I shall be better all my life for these sad hours with you” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 88).

5. were very happy ones. During the first phases of her final decline, Lizzie was not as angelic a patient as her fictionalized counterpart. In early January 1858, her eldest sister Anna wrote to their father. “She has for a month been nervous, cross, & pretty disliked us all, & been wholly unlike herself. . . . She doesn’t care for any of us, & doesn’t want mother near her, thinks I am horrid, & only wants to be let alone to do her sewing.” Once she knew the worst, however, Lizzie became more Beth-like, accepting her fate with almost happy resignation. Anna wrote in the same letter that Lizzie was “very cheerful, & knows the truth, the whole, which she says she has known herself a long time and is glad it is to be so as she is ready & willing to go any time” (Anna Alcott to Bronson Alcott, January 6, 1858, manuscript letter, Houghton Library, Harvard University, bMS Am 1130.9).

6. put it down forever. Lizzie, too, put aside her needle in early March 1858, saying it was “too heavy” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 88).

7. was no help. Bronson Alcott captured the helplessness his family felt during Lizzie’s last days in the following poem:

“Ether,” she begged, “O Father give

“With parting kiss my lips doth seal

“Pure ether once, and let me live

“Forgetful of this death I feel.”

We had it not. Away she turns,

Denied the boon she dying asks,

Her kindling eye with rapture churns,

Immortal goblet takes and quaffs.

8. Shining Ones. When, in The Pilgrim’s Progress, Christian arrives at the River of Death, two men whose clothing shines like gold and whose faces shine like light offer him encouragement and advice. Once Christian has forded the river, the two shining ones greet him again and escort him up to the Celestial City (see Part First, Chapter XIII, Note 6).

9. “stronger when you are here.” Alcott wrote in her journal for November 1857, “Betty loves to have me with her; and I am with her at night, for Mother needs rest. Betty says she feels ‘strong’ when I am near. So glad to be of use” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 86).

10. “blossom in the dust.” The 1659 drama The Contention of Ajax and Ulysses by James Shirley (1596–1666) contains the lines: “Only the actions of the just / Smell sweet, and blossom in their dust.”

11. “lead me home.” Alcott wrote the original version of this poem within a few days of her sister Lizzie’s death. Most of the revisions she made before publishing it here were minor. However, Alcott omitted the original second stanza:

Gentle pilgrim! First and fittest,

Of our little household band;

To journey trustfully before us

Hence into the silent land.

First, to teach us that love’s charm

Grows stronger being riven;

Fittest, to become the Angel

That shall beckon us to Heaven.

12. hands that had led her all her life. Four days before she died, Lizzie “lay in Father’s arms, and called us round her, smiling contentedly as she said, ‘All here!’ ” She held her family’s hands and “kissed us tenderly” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 88).

13. a little sigh. Around three a.m. on March 14, 1858, Elizabeth Sewall Alcott died at age twenty-two. Though she evidently did not see a vision, Alcott and her mother did. Moments after Lizzie’s passing, the two women “saw a light mist rise from the body, and float up and vanish in the air.” Lizzie’s doctor said it was “the life departing visibly” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 89). In an instance of fitting irony, the doctor was named Christian Geist.

When morning came, for the first time in many months the fire was out, Jo’s place was empty,14 and the room was very still. But a bird sang blithely on a budding bough, close by, the snow-drops blossomed freshly at the window, and the spring sunshine streamed in like a benediction over the placid face upon the pillow—a face so full of painless peace, that those who loved it best smiled through their tears, and thanked God that Beth was well at last.15

14. Jo’s place was empty. It may seem curious that it is Jo’s place, not Beth’s, that is specifically described as empty. But in real life, Lizzie’s death did signal a displacement for Louisa within her family. Before Lizzie’s illness, it had seemed logical that Lizzie would care for her parents in their old age, leaving Louisa relatively free to pursue her literary work. With Lizzie gone, Louisa was compelled to balance household concerns with her writing for the rest of her life.

15. Beth was well at last. Lizzie herself referred to her impending death as “get[ting] well” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 88). Five days after Lizzie’s death, Alcott used the same metaphor to transform death into healthy life. She wrote to her cousin Eliza Wells, “Our Lizzie is well at last, not in this world but another where I hope she will find nothing but rest from her long suffering” (Louisa May Alcott, Selected Letters, p. 32). In her journal, Alcott described a sight rather different from Beth’s countenance of painless peace: “What she had suffered was seen in the face, for at twenty-three [sic] she looked like a woman of forty, so worn was she, and all her pretty hair gone.” Alcott added philosophically, “So the first break comes, and I know what death means,—a liberator for her, a teacher for us” (Louisa May Alcott, Journals, p. 89).